1

Running Head: HIERARCHICAL MODEL OF SELF-INJURY AND SUICIDE

Applying the Tripartite Model to the Link between Non-suicidal Self-injury and

Suicidal Risk

自傷行為與自殺危險性的階層預測模式--三元模式的延伸

Ashley Wei-Ting Wang1 and Wen-Yau Hsu1,2

1 Department of Psychology, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 2 Research Center for Mind, Brain, and Learning, National Chengchi University,

Taiwan 王韋婷1、許文耀1,2

1 國立政治大學心理系

2國立政治大學心智、大腦與學習研究中心

Running title: Hierarchical Model of Self-injury and Suicide Corresponding author: Wen-Yau Hsu(許文耀)

Address : National Chengchi University, Department of Psychology, 64, Sec.2, Zhinan Rd. Wenshan District, Taipei City 11605 Taiwan (R.O.C)

2 e-mail: hsu@nccu.edu.tw TEL: 866-2-29387379 FAX: 866-2-29366725 投稿日期:民國 103 年 5 月 1 日 修正日期:民國 103 年 12 月 19 日 修正次數:2 次 內文字數:7753(含表、圖、參考文獻,不含封面與摘要)

3

自傷行為與自殺危險性的階層預測模式--三元模式的延伸

本研究應用Clark與Watson(1991)的憂鬱與焦慮三元模式(the Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression)來說明自傷行為與自殺風險的關連性,本文提出一個自 傷與自殺的階層預測模式:首先,負向情感預測焦慮與憂鬱,而(低)正向情感 預測憂鬱,接著,焦慮可預測自傷行為,而憂鬱則和自殺危險性關連較強。研究 對象為487位大學生,採取自陳式問卷的方式施測,包含自我傷害行為量表、自殺 危險程度量表、正負向情感量表、症狀檢核表-90-修正版。以階層迴歸分析與結構 方程模式來驗證本研究所提出的自傷與自殺的階層預測模式。研究結果支持假設 的自傷與自殺的階層預測模式,另外亦發現,在階層迴歸分析中,焦慮與自傷行 為的關連性高於自殺危險性(雖然預測關係都有顯著)。因此本研究主要的發現 為『自傷行為與自殺危險性的高相關來自於負向情感與焦慮』,不過『憂鬱與(低) 正向情感僅與自殺危險性有關』。所以這個模式有兩條主要路徑:(1)負向情感 能預測與解釋焦慮和憂鬱,且能透過焦慮預測自傷與自殺,唯焦慮對自傷的解釋 力較高;負向情感亦能透過憂鬱預測自殺,但無法透過憂鬱預測自傷。(2)(低) 正向情感能預測與解釋憂鬱,且能透過憂鬱預測自殺。 關鍵字:自殺危險性、自傷行為、焦慮與憂鬱的三元模式、階層關係

4 Abstract

Objectives: The current study applies and expands the Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression to elaborate the link between non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal behavior. We propose a structural model of NSSI and suicidal risk, in which negative affect (NA) predicts both anxiety and depression, low positive affect (PA) predicts depression only, anxiety is linked to NSSI, and depression is linked to suicidal risk.

Method: Four hundreds and eighty seven undergraduates participated. Data were collected by administering self-report questionnaires including the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory, the Scale of Suicidal Risk, and the Symptom Checklist-90-R. We performed hierarchical regression and structural equation modeling to test the proposed structural model.

Results: The results largely support the proposed structural model, with one exception: anxiety was strongly associated with NSSI and to a lesser extent with suicidal risk.

The conclusions of this study are as follows: The co-occurrence of NSSI and suicidal risk is due to NA and anxiety, and suicidal risk can be differentiated by the presence depression and low PA. That is, in this model, there are two pathways. First, NA predicts anxiety and depression, and predicts NSSI and suicidal risk through the

5

mediation of anxiety. NA also predicts suicidal risk through the mediation of depression. Second, low PA predicts depression and also predicts suicidal risk through the

mediation of depression. Further theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Hierarchical relationship, Non-suicidal self-injury, Suicidal risk, The

6

Applying the Tripartite Model to the Link between Non-suicidal Self-injury and Suicidal Risk

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal behaviors cause damage and destruction to oneself through intentional injurious behavior (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006). NSSI is an act of emotional-regulation to avoid negative affect (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006) and lacks lethal intent. In contrast, suicidal behaviors, including suicide attempts and suicidal ideations, are engaged in with intent to end one’s life (Nock, 2010).

NSSI and suicidal behavior are distinguished by intention, frequency, and lethality (Hamza, Stewart, & Willoughby, 2012). Nevertheless, these behaviors substantially co-occur not only in clinical but also in general populations (Guertin, Lloyd-Richardson, Spirito, Donaldson, & Boergers, 2001; Nock et al., 2006). For example, Cooper and colleagues (2005) found that a history of NSSI increased the probability of suicidal behaviors in the general population by 30-fold, while doubling suicidal behavior in clinical populations. Regardless of participant age, gender and socioeconomic status, individuals who engaged in NSSI increased their risk of suicidal behavior (Asarnow et al., 2011; Hamza et al., 2012; Wilkinson, Kelvin, Roberts, Dubicka, & Goodyer, 2011).

7

Thus, while NSSI and suicidal behavior have been viewed as functionally and qualitatively heterogeneous, they are closely linked (Hamza et al., 2012; Stanley, Gameroff, Michalsen, & Mann, 2001). Although many studies of the risk factors for NSSI and suicidal behaviors have been conducted, few studies have examined common mechanisms underlying these behaviors (Hamza et al., 2012).

Theories Explaining the Link between NSSI and Suicidal Behavior

To reconcile this gap in the literature, Hamza and colleagues (2012) reviewed three theories explaining the association between NSSI and suicidal behavior. First, the Gateway Theory posits that NSSI and suicidal behavior share similar experiential qualities and exist at two ends of a continuum. On this continuum, NSSI is a precursor (i.e., a gateway form of self-injury) to suicidal behaviors. Second, Joiner's Theory of Acquired Capability for Suicide suggests that individuals acquire an increased capability for suicide through NSSI behaviors due to a desensitization to the fear and pain associated with suicide. Third, the Third Variable Theory considers that the strong correlation between NSSI and suicidal behavior can be accounted for using a common third variable. For example, psychological distress raises the probability of both NSSI and suicidal behavior (Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007).

8

understanding of the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior, these models remain largely untested. Both the Gateway Theory and Joiner's Theory presume that NSSI is a significant predictor of suicidal behavior, or that NSSI precedes suicidal behaviors. In this case, only via a longitudinal design can researchers examine the temporal direction of the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior. Therefore, studies testing the Gateway Theory and Joiner's Theory are scarce. In addition, there is evidence revealing a group of individuals who engage in suicidal behaviors without having engaged in NSSI and a group of individuals who engage in NSSI without having made suicide attempts. Actually, Cooper and colleagues (2005) found that only 18.3% of individuals with a history of NSSI attempted suicide. All in all, it is arduous to test the Gateway Theory and Joiner's Theory and evidence did not fully support these theories.

Furthermore, even though NSSI has been proven to predict suicidal attempts, it is unknown whether a third variable existed before the act of NSSI to explain the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior. Clearly then, the Third Variable Theory that assumes that a third variable accounts for the co-occurrence of NSSI and suicidal behaviors, should be tested and the third variables should be uncovered before further examination of the temporal order of NSSI and suicidal behavior. We argue that, however, the Third Variable Theory only focuses on shared risk factors. As NSSI and suicidal behavior have been viewed as two distinct constructs, a model accounting for

9

their co-occurrence should incorporate both common and distinguishable risk factors. At present, no sound theoretical perspective identifies both common and specific risk factors associated with NSSI and suicidal behaviors. Therefore, we apply the tripartite model of Clark and Watson (1991) to elaborate the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior. This model not only accounts for features shared by the two target behaviors but also improves upon the Third Variable Theory by identifying unique components that differentiate individuals on NSSI and suicidal behaviors.

Research has emphasized that emotional experience may help in interpretation of findings regarding the functions of NSSI and suicidal behavior. Especially, depression and anxiety could be important reasons explaining why NSSI and suicidal behavior demonstrate high co-variance. Specifically, the Anxiety Reduction Model posits that anxiety plays a prominent role in self-harmers’ psychopathology. Because the

individual lacks other methods for resolving feelings of anxiety, NSSI serves an affect regulation function (Favazza, 1998; Ross & Heath, 2003). In a large scale study using a community sample, Klonsky, Oltmanns, and Turkheimer (2003) found an absence of a relationship between positive affectivity (PA) and NSSI, and a strong and unique relationship between anxiety and NSSI. In light of the Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression (Clark & Watson, 1991), they hypothesized that self-harmers are more anxious than depressed. However, this hypothesis has not been tested. In addition, little

10

is known about whether this conceptual framework can be applied to the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior.

The Tripartite Model

The Tripartite Model has been developed to explain why anxiety is co-morbid with depression. The model proposes that anxiety and depressive disorders have shared and specific components. More explicitly, it suggests that anxiety and depression overlap considerably through a general, nonspecific factor called negative affectivity (NA). Low PA and physiological hyper-arousal, however, are relatively specific to depression and anxiety, respectively.

Explaining the Link between NSSI and Suicidal Risk by the Tripartite Model

Reports of associations between NSSI and anxiety are pervasive in the literature (Stanley et al., 2001; Turell & Armsworth, 2000). Research indicates that individuals experience a sense of relief and reduced anxiety after an episode of NSSI (Klonsky et al., 2003). Theoretical models, such as the anxiety reduction model (Bennun, 1984), explain the specific link between anxiety and NSSI. While anxiety has a strong and direct relationship to NSSI, findings regarding the link between depression and NSSI is less clear. Whereas some studies reported elevated levels of depression in self-harmers

11

(Herpertz, 1995; Stanley et al., 2001), other studies did not support this relationship (Brodsky, Cloitre, & Dulit, 1995; Herpertz, Sass, & Favazza, 1997). Self-harmers are not more likely to have a diagnosis of major depression (Soloff, Lis, Kelly, Cornelius, & Ulrich, 1994; Stanley et al., 2001). In addition, some evidence indicates that major depression is less common in psychiatric patients who deliberately harm themselves when compared with non-self-harming patients (Herpertz et al., 1997; Langbehn & Pfohl, 1993). On the other hand, the strong connection between suicidal risk and depression is obvious. Having recurrent thoughts of death or suicide is one criterion for major depression, as defined by the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2000). Researchers have confirmed the relationship between suicidal behavior and depression, but mixed results have been found for that between suicidal behavior and anxiety (Mazza, 2000; Reinherz et al., 1995).

The findings based on univariate analysis ignored the strong covariance between anxiety and depression, however, so it is unclear whether anxiety or depression makes an additional contribution to variance in NSSI and suicidal risk. The result of

multivariate analysis reported in two studies regarding suicidal risk (Reinherz et al., 1995; Yuen et al., 1996) found that anxiety did not make a significant additional contribution to the variance in suicidal risk. Results from multivariate analysis regarding NSSI were reported in Klonsky and colleagues (2003). They found that

12

anxiety maintained a unique relationship to NSSI over and above depression, whereas the association between depression and NSSI was considerably weaker after controlling for anxiety. Since important links may be better identified in multivariate analysis, we hypothesized that anxiety makes a significant and additional contribution to the variance in NSSI over depression, while depression makes a substantial unique contribution to suicidal risk over anxiety.

Moreover, NSSI has been shown to be more strongly correlated with NA, but not with PA (Hasking et al., 2010; Klonsky et al., 2003; Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007). These findings suggest that NSSI behaviors eliminate negative emotions rather than producing positive emotions. Taken together, the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior can be explained by the Tripartite Model. In this theoretical framework, anxiety co-varies with depression because they share negative emotional affect, while depression is distinguished by diminished positive affect. Therefore, NSSI could be an action aiming at reducing negative affect associated with anxiety, but not at obtaining positive affect. Specifically, we assumed that anxiety is the core distress factor in NSSI, whereas suicidal behavior is specifically linked to depression.

Although the current study posits that NSSI has a strong and direct relationship with anxiety while suicidal behavior is more strongly related to depression, the empirical evidence for this hypothesis is mixed. NSSI might also be related to

13

depression (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005; Nixon, Cloutier, & Aggarwal, 2002). In addition, a link between suicidal behavior and anxiety has been reported (Evans, Hawton, & Rodham, 2004).

The Proposed Structural Model

In light of the Tripartite Model and structural relationships (Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998), we propose a structural model of NSSI and suicidal behavior. In this model, NA and PA are the higher-order, trait-like factors, while anxiety and depression are diagnostic, second order factors representing psychological distress. NSSI and suicidal behaviors are lower order factors. Based on the expansion of the Tripartite Model (Wang, Hsu, Chiu, & Liang, 2012), NA is a general factor that predicts both anxiety and depression, whereas low PA is a specific factor that predicts depression. We proposed that anxiety would predict NSSI, while depression would predict suicidal behaviors. Thus, anxiety and depression are unique features of NSSI and suicidal behavior, respectively. However, NSSI and suicidal behavior might relate both to anxiety and depression. Therefore, we proposed an alternative model in which anxiety and depression predict both NSSI and suicidal behavior (Figure 1).

Aims and Hypotheses

14

structural equation model (SEM) analyses. We hypothesized that anxiety would account for incremental variance in NSSI, but not in suicidal behavior, once partial variance of NA, PA, and depression had been removed from the model. We also hypothesized that depression would account for the incremental variance in the suicidal behavior, but not in NSSI, once partial variance of NA, PA, and anxiety had been removed from the model.

With regard to structural relationships, we predicted that the proposed hierarchical model would be retained, in comparison with the alternative model. Since the

alternative model (the model with more parameters) will always fit the data at least as well as the hypothesized model, whether the hypothesized model fits better and should thus be preferred is determined by the presence of an insignificant chi-square difference (principle of parsimony; Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003).

In examining these two models (Figure 1), the current study aims to clarify how the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior could be explained by a general factor, NA, and distinguished by PA, anxiety, and depression. In other words, the proposed link is that anxiety contributes to NSSI, while depression contributes to suicidal behavior.

Method Participants

15

Participants in this study were 498 undergraduates enrolled in introductory

psychology classes at four universities in Taiwan. With the teachers’ approval, students were invited to complete a battery of four measures during class. Eleven students completed less than a half of the whole questionnaire. These students were excluded from analyses. A complete set of answers was provided by 487 students. Of these, 325 (66.74%) were female, and 162 (33.26%) were male. The average age of the

participants was 19.77 years (S.D. = 1.60), with a range of 18 to 33 years.

Measures and Procedures

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The

PANAS consists of two 10-item scales that measure positive affect (PANAS-P) and negative affect (PANAS-N). The trait version of the PANAS was adopted in the current study. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘‘very slightly or not at all’’ to 5 = ‘‘extremely.’’ The trait version of the PANAS-P and PANAS-N have

consistently emerged as two relatively independent dimensions, and have demonstrated high internal consistency and stable over a 2-month time period. We use the Chinese version of the PANAS, translated by Wang et al., (2012). The Chinese version of the PANAS has shown to be highly internally consistent (the alpha reliabilities of the PANAS-P and the PANAS-N were .83 and .87, respectively). In the current study, both

16

the PANAS-P (α = .83) and the PANAS-N (α = .90) subscales exhibited high internal consistency.

Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001). The DSHI is a 17-item

self-report, yes/no scale that explores 17 types of deliberate self-harm. Following the procedure of translation and back-translation (Brislin, 1986), the DSHI was translated into Chinese. In the Chinese version, two additional types of self-harm behavior, “hair pulling” and “punching a wall,” were included, based upon an investigation of

self-harm behaviors in Taiwan (Chen, 2006), for a total of 19 behaviors. The DSHI was used to assess the frequency and type of self-harm behaviors. Respondents were asked if they had deliberately engaged in any of the 19 types of direct physical self-harm during the past 12 months. For each positive response, participants were instructed to rate number of times (frequency) that they had conducted these behaviors. Frequencies for each item were tabulated to determine the overall frequency of NSSI. The internal consistency of the DSHI in the present study was acceptable (α = .73). In the current study, NSSI is reported as the number of self-harm behaviors (NSSIw) and the frequency of NSSI (NSSIf).

Scale of Suicidal Risk (SSR; Hsu & Chung, 1997). The SSR was developed to

measure the risk of suicide. The SSR is a 24-item, 4-point Likert scale that measures the intensity of an individual’s suicidal ideation, suicidal intention, previous suicidal

17

attempts, plans to commit suicide, and preparation for suicide. Hsu and Chung reported an internal consistency on the SSR of α = .85-.90. Test-retest reliability over 3 weeks was high (r = .88-.90). The SSR has shown good convergence and criterion validity. The SSR also has excellent predictive validity for screening high risk populations (Hsu & Chung, 1997). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the SSR was very good (α= .90).

Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1983). In this study, the

depression (13 items) and anxiety (10 items) scales of the SCL-90R were used to assess the severity of depression and anxiety. The SCL-90-R had excellent internal consistency in the current study (α = .91 and .88 for anxiety and depression, respectively).

Following published guidelines (Brislin, 1986), the SCL-90R was translated into Chinese.

Analysis Plans

To test the hypothetical model, hierarchical regression analyses were used to assess the incremental validity of specific factors over more general traits. Because these factors are invariably correlated, Kotov, Watson, Robles, and Schmidt (2007) suggested that a hierarchical approach (as opposed to simultaneous entry of the

18

general factors. That is, the independent contributions of the specific and unique factors can only be evaluated appropriately by partialling out the variances of correlated general factors.

To evaluate structural relationships, we adopted a structural equation model (SEM) using Lisrel 8.7 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2004). The models are illustrated in Figure 1. The latent variables at the same level are conceptually correlated, so correlations between NA and PA, anxiety and depression, and NSSI and suicidal risk were added. We created parcels for each measurement model for two reasons. First, the focus of the model testing is structure rather than measurement. Creating parcels increases the weighting of the structural aspect. Second, because lower item subject ratios may lead to instability of the model solution, creating parcels can be profitably used to increase the ratio (Marsh & Hocevar, 1988). Following the rule for building parcels (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002), the dimensionality of each measurement model should be determined a priori. Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) with an oblique rotation were conducted as suggested by Little and colleagues. Measurement models of the PANAS-P, the PANAS-N, depression, anxiety, and the SSR were all unidimensional. Since all measurement models were unidimensional, it was appropriate to apply parceling items. The PANAS-P, the PANAS-N, anxiety, depression and the scale of suicidal risk were even-odd halved. The number NSSI types (NSSIw) and NSSI frequencies (NSSIf) are

19 indicators of NSSI (see Figure 2).

In sum, examining both incremental validity of specific factors over more general traits and hierarchical structural relationships can provide reliable evidence for the hypothetical model as suggested by Wang and colleagues (2012).

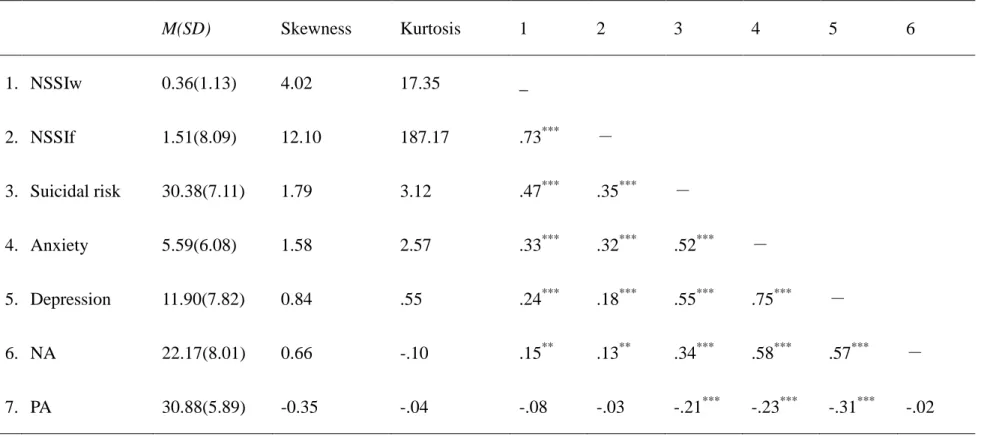

Results Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations among all of the study measures. Seventy-seven participants (15.81%) reported at least one incident of non-suicidal self-injury during the past 12 months. Among the individuals who committed NSSI behaviors, NSSI behaviors were reported by 46.75% (n=36) of the male students and 53.25% (n=41) of the female students, no gender difference been found (χ (1)2 = .33, p > .05). The ten most frequently reported types of NSSI were

“punching a wall” (59.7%), “punching oneself” (26.0%), “self-cutting” (24.7%), “scratching” (23.4%), “biting” (22.1%), “hair pulling” (19.5%), “head banging” (13.0%), “sticking sharp objects into the skin” (10.4%), “preventing wounds from healing” (10.4%), “carving words” (6.5%), and “carving pictures” (6.5%). Only

“self-cutting” and “biting” showed gender differences with female participants reporting

20 4.77,p <.05).

The mean number of NSSI methods reported by the participants was 2.42.

Thirty-seven (48.1%) people reported engaging in one type of NSSI, and more than half of self-harming individuals reported using multiple methods to harm themselves. In total, 15 (19.5%) participants reported two types of NSSI, 7 (9.1%) reported three types, and 17 (23.4%) reported four types of NSSI.

The vast majority of self-harming individuals had harmed themselves on more than one occasion in the last 12 months. Mean frequency of NSSI behaviors was 10.10 times (SD=18.85), ranging from 1 to 140 times. Nine people (11.7%) reported a single

incident of NSSI, while 63 people (81.8%) reported having more than two incidents. Of these 63 participants, 23.4% reported two NSSI incidents, and 11.7% reported three NSSI incidents.

Mean scores on the SSR was 30.38 (SD = 7.11), ranging from 24 to 61. On item 3 of the SSR, “I think about killing myself” (suicidal ideation), 24.64% of the participants answered “sometimes,” “very often,” or “always.” On item 17 “I have made a suicide attempt” (suicidal attempts), 5.96% of them answered ”once,” 1.84% of them answered “more than twice,” and 0.21% answered ”often.”

The findings also revealed that 8.42% (N = 41) of the sample reported both suicidal ideation and attempts, while 16.22% (N = 79) reported suicidal ideation only, and

21

7.39% (N = 36) reported suicidal attempts only. When the overlap between NSSI behavior and suicidal attempts was evaluated, 4.52% (N = 22) of the sample reported both NSSI behavior and suicidal attempt, 11.29% (N = 55) reported NSSI without suicidal attempts, 3.49% (N = 17) reported suicidal attempts without NSSI.

As shown in table 1, NSSIw and NSSIf were positively correlated with suicidal risk, suggesting that non-suicidal self-injury was related to suicidal risk. The Depression and Anxiety subscales also positively correlated with NSSIw, NSSIf, and suicidal risk. PANAS-N was positively correlated with all the study measures. PANAS-P was negatively correlated with suicidal risk, anxiety and depression. Correlations between PANAS-P and NSSIf and NSSIw were both nonsignificant.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses

Linear regression models assume that the conditional distribution of Y given X is normal. Although the distributions of the dependent variables (NSSI and suicidal risk) are nonnormal (see Table 1), P–P plots (probability–probability plots) for these

variables fell on the 45° line from (0, 0) to (1, 1) at an appropriate level. Therefore, we did not adjust the value of the dependent variables before conducting hierarchical regression analyses.

22

individually. To determine the specific incremental variance accounted for by anxiety, the independent variables were entered sequentially in the following order: NA, PA, depression, and finally anxiety. Similarly, to examine the specific incremental variance accounted for by depression, variables were entered in the following order: NA, PA, anxiety, and depression. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2.

PANAS-N significantly predicted all of the dependent variables. PANAS-P significantly predicted suicidal risk but did not predict NSSIw and NSSIf. Anxiety contributed significant incremental variance to each indicator of NSSI after controlling for NA, PA, and depression. In contrast, depression did not account for additional variance in either NSSIf or NSSIw after controlling for NA, PA, and anxiety. These finding suggest that anxiety is a valid predictor of NSSI, but depression did not predict NSSI. When suicidal risk was examined, depression contributed significant incremental variance once NA, PA, and anxiety were controlled. Anxiety also made an independent contribution to the incremental variance of suicidal risk after NA, PA, and depression were controlled. Specifically, the amount of variance explained by depression was larger than the amount due to anxiety (ΔR2=4.8%, 2.5%).

SEM Analyses

23

Satorra and Bentler (1994) correction to chi-square were used to examine the

hierarchical relationships (Figure 1), because some of the measures were not normally distributed (see Table 1). A recent review regarding handling non-normal variables in SEM (Kupek, 2005) suggested the use of RML to obtain the standard errors of SEM parameters as these are most affected by departure from multivariate normality.

Figure 2 presents the standardized solutions of the hypothesized structural model. Several indicators of model fit were used to assess the congruence between the data and the hypothesized model, in accordance with Hu and Bentler (1999). These indicators include the Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI), the Non-Norm Fit Index (NNFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness-Of-Fit Index (GFI), the Adjusted

Goodness-Of-Fit Index (AGFI), the Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

The hypothetical model provided an excellent fit to the data [χ2 (46) = 111.67, χ2/df = 2.43, less than 3, indicating very good model fit (Carmines & McIver, 1981)]. The NFI (.99), the NNFI (.99), the GFI (.96), the AGFI (.94), and the CFI (1.00) were all above .90, whereas the SRMR (.058) and the RMSEA (.036) were below or close to .05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; McDonald & Ho, 2002). The alternative model resulted in a very good fit [χ2 (44) = 106.90, χ2/df = 2.43, NFI (.99), NNFI (.99), GFI (.97), AGFI (.94), CFI (.99), SRMR (.058), and RMSEA (.037)]. The difference between these two

24 models [Δχ2

(2) = 4.77, p > .05] was not significant. For the principle of parsimony, the hypothesized model should be favored. In the alternative model, however, only the path from anxiety to suicidal risk was significant (β = .17, p<.05). The path from depression

to NSSI was not significant in the alternative model. Moreover, anxiety was a stronger predictor of NSSI than suicidal risk (β =.42 & .17). Thus, the hypothesized structural

model was retained.

Discussion

In accordance with Klonsky et al. (2003) and the Tripartite Model (Clark & Watson, 1991), the current study proposed a hierarchical model to explain the link between NSSI and suicidal behavior. The proposed model presents structural relationships between NA, PA, anxiety, depression, NSSI, and suicidal risk, explaining the etiological

characteristics of NSSI and suicidal risk. In agreement with the Tripartite Model, NA predicted both anxiety and depression, while PA only predicted depression. The results indicate that depression is linked only to suicidal risk. Moreover, anxiety is specifically associated with NSSI but may also contribute to suicidal risk, although anxiety is linked to suicidal risk to a considerably lesser extent than to NSSI. These relationships were confirmed through correlational analyses, hierarchical analyses, and SEM.

25

the link between NSSI and suicide and explore the unique factor that distinguishes them. The results of the current study revealed a link between NSSI and suicidal behavior through two shared characteristics: the higher order factor, NA, and anxiety. Consistent with theoretical models that presume NA to be the key factor relating to NSSI and suicide attempts (e.g., Chapman & Dixon‐Gordon, 2007; Nixon et al., 2002), our

findings bolster the view that NA is a common factor in NSSI and suicide attempts. Chapman and colleagues (2006) proposed the Experiential Avoidance Model that regards NSSI as an emotional regulation strategy used to compensate for unwanted inner experiences and negative circumstances. Similarly, prior research has found that suicide is related to negative emotions, including depressive mood, guilt, loneliness, and neuroticism (Cox, Enns, & Clara, 2004; Kaslow et al., 2002; Lasgaard, Goossens, & Elklit, 2011). Baumeister (1990) asserts that individuals are highly distressed (both depressed and anxious) before committing suicide. Taken together, the correlation between NSSI and suicidal behavior can be attributed to NA.

Empirical evidence and theoretical models have pointed out that increased risk for both NSSI and suicidal behavior is associated with perceived level of psychological distress or NA. The current study further elaborates the specific emotional experience that self-harmers and individuals with suicidal risk may have under the NA umbrella: namely, anxiety and depression. Previous studies have investigated this relationship

26

using bivariate correlations and group comparisons (e.g., Cooper et al., 2005;

Muehlenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007; Nock et al., 2006), although these methods may be insufficient to account for the complex relationships between NSSI and suicide. Importantly, due to the lack of a theoretical basis in the literature reviewed, the current study adopted and expanded Klonsky et al. (2003), the Tripartite Model, and the Structural Model (Brown et al., 1998; Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998; Wang et al., 2012) to develop a hierarchical model of NSSI and suicidal risk.

Anxiety is another common component for NSSI and suicidal risk. It should be noted that anxiety was more strongly related to NSSI than suicidal risk, implicating a specific link between anxiety and NSSI. These findings are consistent with Klonsky et al. (2003) and the Anxiety Reduction Model (Favazza, 1998; Ross & Heath, 2003). It is posited that increased levels of anxiety are specific to the act of self-harm. Experiencing a sense of relief (Briere & Gil, 1998) and physiological evidence for tension reduction was observed in self-harmers after episodes of self-harm (Brain, Haines, & Williams, 1998). Taken together, the findings from past research and the current study suggest that self-harmers tend to be anxious and that NSSI may be a strategy for reducing anxiety (Ross & Heath, 2003). Given this study utilized a cross-sectional design; the findings could not inform direct evidence for the causal role of anxious mood before NSSI. Future research should investigate whether reducing symptoms of anxiety can be

27 effective in treating deliberate self-harm.

Another important finding of the current study is that suicidal risk can be distinguished from NSSI by depression and lack of PA. Previous research has shown that while NSSI is unrelated to low PA (e.g., Briere & Gil, 1998; Klonsky, 2009),

suicide is characterized by diminished PA (e.g., Hirsch, Duberstein, Chapman, & Lyness, 2007; Joiner et al., 2001). Our findings also parallel the notion of Klonsky et al. (2003) that the Tripartite Model accounts for the absence of a relationship between NSSI and PA. Therefore, while NSSI may be work to diminish NA, it does not aim at bolstering PA. Our findings are inconsistent with past research that found a correlation between NSSI and depression (e.g., Briere & Gil, 1998; Evans et al., 2004; Klonsky et al., 2003). This inconsistency can be explained as follows. The correlation between NSSI and depression are significant in zero-order correlations. However, significant relationships were not observed in the results of the SEM and hierarchical regression once variance due to anxiety was removed from the models. Klonsky and colleagues (2003) have argued that the spurious correlation between NSSI and depression was due to the contribution of anxiety. In the current study, we adopted multivariate analyses to account for the specific and unique emotional experience that is significantly and directly experienced and aware by individuals engaged in NSSI or suicidal behavior.

28

and further develop theories of the relationship between NSSI and suicide. According to Hamza and colleagues (2012), NSSI is a precursor of suicide. Thus, future research efforts might address the psychological mechanisms underlying increased risk of suicide in self-harmers. The present study highlighted the role that NSSI behavior plays in reducing anxiety and implicated depression as a warning of suicidal risk. We call upon clinical practices to deal with anxiety in individuals engaged in NSSI and to intervene along the lines of the psychopathological mechanisms of anxiety. In cases of prevented suicide, depression, and the lack of positive affect should be observed, as recommended by Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez (2007). With regards to the

Helplessness-Hopelessness Model, Abramson, Metalsky, and Alloy (1989) argued that anxiety and depression are at two ends of a continuum and that different dysfunctional cognitive features are necessary for anxiety to develop into depression. Future research could extend the Tripartite Model by exploring the role of these cognitive features on anxiety and depression. To date, research regarding NSSI has mostly adopted the view of emotional regulation (Chapman et al., 2006; Nock & Prinstein, 2004) without assessing cognitive features in individuals with a history of NSSI. Therefore, another promising avenue of investigation is the cognitive psychopathology of anxiety and depression and how this psychopathology is linked to NSSI and suicide.

29

suicidal ideation, and 8.01% reported suicide attempts. Compared to a Turkish study of undergraduates with 15.4% NSSI, 11.4% suicidal ideation, and 7.1% suicide attempts (Toprak, Cetin, Guven, Can, & Demircan, 2011), our sample had higher rates of suicidal ideation but similar rates of NSSI and suicide attempts. The rate of NSSI in the present study was also similar to the studies of Favazza, DeRosear, and Conterio (1989) and Ross and Heath (2002), both of which included undergraduate students. In conclusion, the incident rates of NSSI and suicidal risk of Taiwanese undergraduates are comparable with those of other countries.

Limitations

The current study had some limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, our findings might preclude causal inferences. To obtain more reliable data, further research is needed to replicate our findings and apply a longitudinal design. Second, we used an undergraduate sample rather than a clinical sample to address the

link between NSSI and suicide. However, many researchers have advocated conceptualizing psychopathology as a dimensional construct (e.g., Kotov et al., 2007).

Estimates and prevalence of NSSI and suicidal behavior may be inflated in a clinical sample (Klonsky et al., 2003). In this regard, both general and clinical samples are needed. It therefore would be particularly informative to replicate these analyses in a

30

large clinical sample. Third, as can be seen in the hierarchical analyses, little variance in the NSSI indicators was explained when all predictors were included (11%). This lack

of variance may be explained by the low incidence of NSSI behaviors in our undergraduate sample. In addition, other factors not examined in this study, such as hostility, may be crucial for NSSI (Ross & Heath, 2003). However, our sample had a similar rate of NSSI as compared to other undergraduate samples. Finally, the current study failed to find a unique contributor to NSSI. Further examination of NSSI-related

factors in the context of a Hierarchical Model of NSSI and suicide would permit powerful elaboration of the link between NSSI and suicide. Another limitation concerns

the function NSSI serves. The current model supports NSSI in relation to diminishing NA rather than producing PA. However, in the DSM-V (APA, 2013), it is proposed that

an individual engaging in NSSI has the expectation of either enhancing PA or eliminating NA. Whether NSSI is an act motivated by producing PA is not the aim of

the current study. Future research with adequate design is obviously required with respect to the motivation for NSSI acts, however. Despite these limitations, the current

study has contributed to the literature regarding explaining the link between NSSI and suicidal risk. We articulated a structural model that may help disentangle the common

31 致謝

本研究改寫自原作者之一-謝光桓之碩士論文,本研究撰寫之時,他正與癌 症病魔搏鬥,本文完成並投稿時,因其辭世而未能列於作者。僅以此文紀念他。

32 References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358-372. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Asarnow, J. R., Porta, G., Spirito, A., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., . . . McCracken, J. (2011). Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(8), 772-781.

Baumeister, R. F. (1990). Suicide as escape from self. Psychological Review, 97(1), 90-113.

Bennun, I. (1984). Psychological Models of Self‐Mutilation. Suicide and

Life-Threatening Behavior, 14(3), 166-186.

Brain, K. L., Haines, J., & Williams, C. L. (1998). The psychophysiology of

self-mutilation: Evidence of tension reduction. Archives of Suicide Research, 4(3), 227-242.

33

Briere, J., & Gil, E. (1998). Self‐mutilation in clinical and general population samples:

Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(4), 609-620.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. L. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research (pp. 137-164). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Brodsky, B. S., Cloitre, M., & Dulit, R. A. (1995). Relationship of dissociation to self-mutilation and childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(12), 1788-1792.

Brown, T. A., Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(2), 179-192.

Carmines, E. G. & McIver, J. P. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bhrnstedt, & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social Measurement: Current Issues (pp. 65-115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

Publications.

Chapman, A. L., & Dixon‐Gordon, K. L. (2007). Emotional Antecedents and Consequences of Deliberate Self‐Harm and Suicide Attempts. Suicide and

34 Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(5), 543-552.

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(3), 371-394.

Chen, Y. W. (2006). Environmental Factors Associated with Self-Mutilation among a Community Sample of Adolescents. Formosa Journal of Mental Health, 19, 95-124.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316-336.

Cooper, J., Kapur, N., Webb, R., Lawlor, M., Guthrie, E., Mackway-Jones, K., & Appleby, L. (2005). Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 297-303.

Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Clara, I. P. (2004). Psychological dimensions associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(3), 209-219.

Derogatis, L. R. (1983). SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring and procedures manual-II for the revised version. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research.

35

phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(8), 957-979.

Favazza, A. R. (1998). The coming of age of self-mutilation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186(5), 259-268.

Favazza, A. R., DeRosear, L., & Conterio, K. (1989). Self‐Mutilation and Eating

Disorders. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 19(4), 352-361. Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the

Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 253-263.

Guertin, T., Lloyd-Richardson, E., Spirito, A., Donaldson, D., & Boergers, J. (2001). Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(9),

1062-1069.

Hamza, C. A., Stewart, S. L., & Willoughby, T. (2012). Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature and an integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 482-495.

Hasking, P. A., Coric, S. J., Swannell, S., Martin, G., Thompson, H. K., & Frost, A. D. (2010). Brief report: Emotion regulation and coping as moderators in the relationship between personality and self-injury. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5),

36 767-773.

Herpertz, S. (1995). Self‐injurious behaviour Psychopathological and nosological characteristics in subtypes of self‐injurers. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica,

91(1), 57-68.

Herpertz, S., Sass, H., & Favazza, A. (1997). Impulsivity in self-mutilative behavior: psychometric and biological findings. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 31(4), 451-465.

Hirsch, J. K., Duberstein, P. R., Chapman, B., & Lyness, J. M. (2007). Positive affect and suicide ideation in older adult primary care patients. Psychology and Aging, 22(2), 380-385.

Hsu, W. Y., & Chung, J. M. (1997). Constructing a scale of suicidal risk and testing its reliability and validity. Formosa Journal of Mental Health, 10, 1-17.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Jöreskog, K., & Sörbom, D. (2004). LISREL 8.7 Computer Software Lincolnwood. IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Joiner, T. E., Pettit, J. W., Perez, M., Burns, A. B., Gencoz, T., Gencoz, F., & Rudd, M. D. (2001). Can positive emotion influence problem-solving attitudes among

37

suicidal adults? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(5), 507-512.

Kaslow, N. J., Thompson, M. P., Okun, A., Price, A., Young, S., Bender, M., . . . Parker, R. (2002). Risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in abused African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 311-319.

Klonsky, E. D. (2009). The functions of self-injury in young adults who cut themselves: Clarifying the evidence for affect-regulation. Psychiatry Research, 166(2), 260-268.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1501-1508.

Kotov, R., Watson, D., Robles, J. P., & Schmidt, N. B. (2007). Personality traits and anxiety symptoms: The multilevel trait predictor model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(7), 1485-1503.

Kupek, E. (2005). Log-linear transformation of binary variables: a suitable input for SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 12(1), 28-40. Langbehn, D. R., & Pfohl, B. (1993). Clinical correlates of self-mutilation among

38

Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., & Elklit, A. (2011). Loneliness, depressive

symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 137-150. Laye-Gindhu, A., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2005). Nonsuicidal self-harm among

community adolescents: Understanding the “whats” and “whys” of self-harm.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(5), 447-457.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151-173.

Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1988). A new, more powerful approach to

multitrait-multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(1), 107-117.

Mazza, J. J. (2000). The Relationship Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptomatology and Suicidal Behavior in School‐Based Adolescents. Suicide and

Life-Threatening Behavior, 30(2), 91-103.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64-82.

Mineka, S., Watson, D., & Clark, L. (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 377-412.

39

Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2007). Risk for suicide attempts among

adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 11(1), 69-82.

Nixon, M. K., Cloutier, P. F., & Aggarwal, S. (2002). Affect regulation and addictive aspects of repetitive self-injury in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(11), 1333-1341.

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339-363. Nock, M. K., Joiner, T. E., Gordon, K. H., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Prinstein, M. J.

(2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144(1), 65-72.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885-890.

Reinherz, H. Z., Giaconia, R. M., Silverman, A. B., Friedman, A., Pakiz, B., Frost, A. K., & Cohen, E. (1995). Early psychosocial risks for adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(5), 599-611.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(1),

40 67-77.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. L. (2003). Two Models of Adolescent Self‐Mutilation. Suicide

and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(3), 277-287.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent Variable Analysis: Applications to Developmental Research (pp. 399-419).

Newbury Park: Sage.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23-74.

Soloff, P. H., Lis, J. A., Kelly, T., Cornelius, J., & Ulrich, R. (1994). Self-mutilation and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8(4), 257-267.

Stanley, B., Gameroff, M. J., Michalsen, V., & Mann, J. J. (2001). Are suicide attempters who self-mutilate a unique population? American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(3), 427-432.

Toprak, S., Cetin, I., Guven, T., Can, G., & Demircan, C. (2011). Self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among college students. Psychiatry research, 187(1), 140-144.

41

Turell, S. C., & Armsworth, M. W. (2000). Differentiating incest survivors who self-mutilate. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(2), 237-249.

Wang, W.-T., Hsu, W.-Y., Chiu, Y.-C., & Liang, C.-W. (2012). The hierarchical model of social interaction anxiety and depression: The critical roles of fears of evaluation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 215-224.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070.

Wilkinson, P., Kelvin, R., Roberts, C., Dubicka, B., & Goodyer, I. (2011). Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 495-501.

Yuen, N., Andrade, N., Nahulu, L., Makini, G., McDermott, J. F., Danko, G., . . . Waldron, J. (1996). The rate and characteristics of suicide attempters in the native Hawaiian adolescent population. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26(1), 27-36.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Measures. M(SD) Skewness Kurtosis 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. NSSIw 0.36(1.13) 4.02 17.35 _ 2. NSSIf 1.51(8.09) 12.10 187.17 .73*** - 3. Suicidal risk 30.38(7.11) 1.79 3.12 .47*** .35*** - 4. Anxiety 5.59(6.08) 1.58 2.57 .33*** .32*** .52*** - 5. Depression 11.90(7.82) 0.84 .55 .24*** .18*** .55*** .75*** - 6. NA 22.17(8.01) 0.66 -.10 .15** .13** .34*** .58*** .57*** - 7. PA 30.88(5.89) -0.35 -.04 -.08 -.03 -.21*** -.23*** -.31*** -.02

Note. Note. PANAS-N = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, negative affect subscale; PANAS-P = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, positive affect subscale; NSSIw=number of types of non-suicidal

self-injury; NSSIf=frequencies of non-suicidal self-injury.

Table 2. Results of the Hierarchical Regression Analyses Independent

variable

Dependent Variable

NSSIw NSSIf Suicidal risk

Regression 1 Step 1 β Step 2 β Step 3 β Step 4 β ΔR2 (%) Step 1 β Step 2 β Step 3 β Step 4 β ΔR2 (%) Step 1 β Step 2 β Step 3 β Step 4 β ΔR2 (%) NA .15*** .15*** .02 -.06 2.2*** .13** .13** .04 -.06 1.7* .34*** .34*** -.06 -.00 11.7*** PA -.07 -.01 .01 0.5 -.03 .02 .04 0.1 -.20*** -.05 -.04 3.9*** Depression .22*** .00 2.9*** .16** -.10 1.5** .50*** .35*** 15.0*** Anxiety .37*** 5.4*** .43*** 7.8*** .25*** 2.5*** Regression 2

NSSIw NSSIf Suicidal risk

Anxiety

.37*** .37*** 8.3*** .38*** .43*** 8.8*** .45*** .25*** 12.7***

Depression

n.s. n.s.

Note. PANAS-N = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, negative affect subscale; PANAS-P = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, positive affect subscale; NSSIw=number of types of non-suicidal self-injury;

NSSIf=frequencies of non-suicidal self-injury. For Regression 2, Step 1 and 2 are as same as Regression 1.

45

Figure 1. The hypothesized structural model (left) and the alternative model (right).

NA = negative affect; PA = positive affect; Anx. = anxiety; Dep. = depression; Sui = suicidal risk; NSSIw = number of types of non-suicidal self-injury; NSSIf =

frequencies of non-suicidal self-injury.

Figure 2. The completely standardized solution of the hypothesized structural model.

All of the regression coefficients of the paths in the model reached significance at the α = .05 level. NA = negative affect; PA = positive affect; Anx. = anxiety; Dep. =

depression; Sui = suicidal risk; NSSIw = number of types of non-suicidal self-injury; NSSIf = frequencies of non-suicidal self-injury. The subscripts “o” and “e” indicate that the observed variables are the sum of odd and even items, respectively.

46

The hypothesized structural model The alternative model

NA PA Anx. Dep. NSSI Sui. NA PA Anx. Dep. NSSI Sui.

47

NA PA

Anx. Dep.

NSSI Sui.

NAo NAe PAo PAe

Anx.o

Anx.e

Dep.o

Dep.e

NSSIw NSSIf Sui.o Sui.e

.96 .86 .80 .91 .94 .93 .92 .87 .96 .77 .95 .92 .63 .62 -.20 .60 .33 .08 .26 .36 .16 .11 .13 .15 .25 .09 .41 .09 .16