兒童在同儕對話中的拒絕策略 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Children’s Refusal Strategy in Peer Talk. By Yih–ru Jong. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. A Thesis Submitted to. the Graduate Institute of Linguistics. n. al. i in C Partial Fulfillment of U then hengchi. Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July 2012. v.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. Copyright © 2012 Yih-ru Jong All Rights Resevered iii. v.

(4) Acknowledgement. 我完成了! 此時此刻的我總算能大聲喊出這句期待已久的話。四年多的研究 所時光,我常想,真的有走到終點的一天嗎? 幸好這一路上許多人的幫助和打氣, 支持著我不斷向前,也為這階段的求學過程畫下完美句點。 在這四年中,最要感謝的是我的指導教授黃瓊之老師,一直以來受到了老師 很多的照顧。在一開始尋找論文題目時遭遇許多困難,讓我很灰心,那時老師給 了我很多鼓勵,也引導我朝不同的方向思考,最後才順利將題目定下來。而每次 和老師討論論文,老師總能精準地點出我論文的問題、思考的盲點,也同時給我 很多寶貴的意見,老師縝密的思考和邏輯總讓我佩服。而老師的肯定和鼓勵,讓 常常沒有信心的我,有了前進的力量;溫柔的關心和安慰,也為研究生的苦悶生 活注入一股暖流。能跟著老師學習語言學的知識和做人處事的態度,真的讓我心 中充滿感激! 另外,也要向我的口試委員徐嘉慧老師以及陳淑惠老師表達我最大 的感激,謝謝您們提供了這麼多寶貴的意見及鼓勵,讓我的論文可以更趨完善。 在語言所的這幾年,還要感謝所上老師們的教導,讓我學得許多寶貴的知識。 感謝詹惠珍老師在大學時的教導,因為老師充滿熱情又生動活潑的教學,開啟了 我對語言學的興趣;感謝幽默風趣的何萬順老師、充滿活力的蕭宇超老師、熱情 美麗的萬依萍老師,您們的豐富學識讓我這四年收穫滿滿。還要感謝總是默默給. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. 我們支持的惠鈴助教,每當有問題時總能從你身上得到解答,心情不好或失去信 心時跟你聊聊,就會覺得好多了,真的謝謝你!. sit. n. al. er. io. 當然,我也要感謝和我一起共患難的研究所同學們,因為有你們的陪伴和支 持,我才能度過每一次的難關。特別要感謝以舷,謝謝你總是聽我訴苦,在我不 開心時給我最多的安慰和鼓勵,你不時的搞笑演出,也讓我的生活充滿樂趣,因 為有你的陪伴,讓我知道艱辛的論文之路我並不孤單。也謝謝苡瑄、愷玟、怡璇、 采君、孟英等好朋友,和你們一起分享生活,讓我的研究生活充滿歡笑。還要謝 謝工作室的夥伴們,感謝郁彬學長提供了很多學術上的寶貴意見,而曉晴學姐和 妃容學姊也給了我不少鼓勵和經驗傳授,讓我的論文之路能更順利;感謝侃彧、 美杏、建銘、亭伊,你們在工作室的陪伴和偶而的閒聊,紓解了我不少壓力。 最後,我要特別感謝我的父母。從小到大你們對我無微不至的關心和照顧,. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 我真的充滿感激,謝謝你們讓我總能無憂無慮的專心在學業上,也讓我知道你們 永遠是我的支柱,不論遇到甚麼事,家都是我溫暖的避風港。謝謝爸爸總是比我 還擔心論文的進度,不時的打電話來關心我,給我很多的鼓勵和信心,也很抱歉 讓你煩惱了這麼久,這次我是真的要畢業囉! 也謝謝媽媽總是相信我做的每個決 定,給我自由發展的空間。因為有你們的支持,我才能走到今天,能當你們的女 兒,真的很幸運!我愛你們!也要謝謝淡定的劉胖胖,陪我分享喜怒哀樂,在我難 過灰心的時候,給我溫暖的支持和鼓勵,感謝你一直以來的包容和陪伴。 再次感謝一路上曾幫助過我的每個人,謝謝你們! iv.

(5) Table of Contents. Chapter 1 Introduction............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background and motivation ............................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purposes of the Study ...................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2 Literature Review ..................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Adults’ refusal ................................................................................................................. 5. 政 治 大. 2.2 Children’s refusal .......................................................................................................... 10. 立. 2.3 Refusal and gender ........................................................................................................ 17. ‧ 國. 學. Chapter 3 Methodology ........................................................................................................... 23 3.1 Subjects and data ........................................................................................................... 23. ‧. 3.2 Procedures of data analysis ........................................................................................... 25. sit. y. Nat. 3.3 Coding categories .......................................................................................................... 26. er. io. Chapter 4 Data Analysis .......................................................................................................... 31. al. v i n Ch 4.1.1 Simple negation ...................................................................................................... 33 engchi U n. 4.1 Children’s use of refusal strategies................................................................................ 31. 4.1.2 Reason .................................................................................................................... 33 4.1.3 Nonverbal avoidance .............................................................................................. 35 4.1.4 Alternative .............................................................................................................. 37 4.1.5 Verbal avoidance .................................................................................................... 38 4.1.6 Dissuade interlocutor .............................................................................................. 39 4.1.7 Conditional acceptance ........................................................................................... 41 4.1.8 Negated ability........................................................................................................ 42 4.1.9 Counterclaim .......................................................................................................... 43 4.1.10 Physical force ....................................................................................................... 43 v.

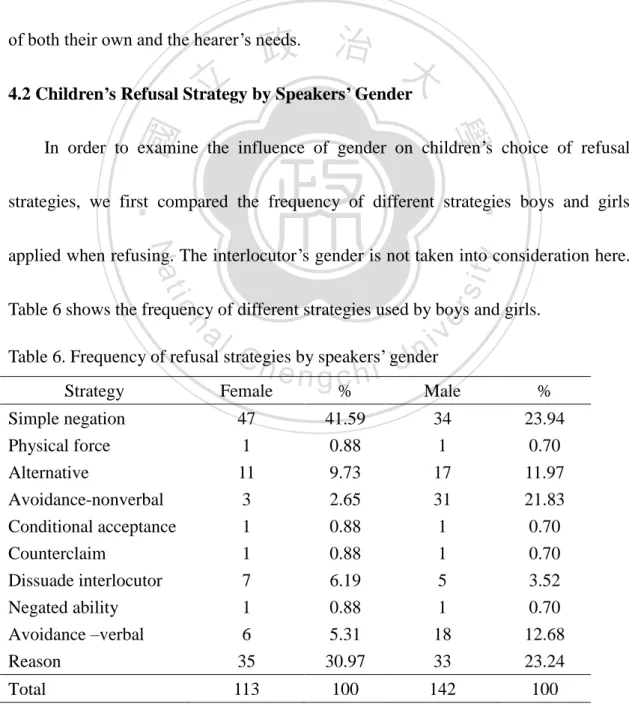

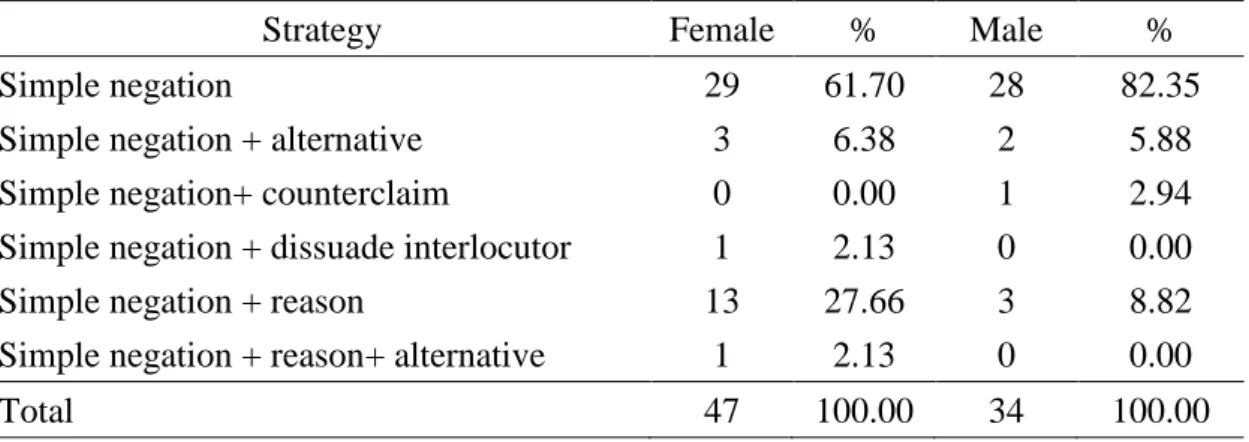

(6) 4.1.11 Combination of refusal strategies ......................................................................... 44 4.2 Childrens’ Refusal Strategy by Speakers’ Gender ........................................................ 47 4.3 Children’s Refusal Strategies by Speakers’ and Interlocutors’ Gender ........................ 51 4.4 Children’s refusal sequence ........................................................................................... 59 Chapter 5 Discussion and Conclusion ..................................................................................... 67 5.1 Children’s refusal strategies and maintenance of friendship ......................................... 67 5.2 Children’s refusal strategies and the perspective taking ability .................................... 69 5.3 Gender differences in Children’s Refusal Production ................................................... 70 5.4 Children’s refusal in sequence....................................................................................... 73. 政 治 大. 5.5 Limitation and suggestion ............................................................................................. 74. 立. References ............................................................................................................................... 76. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

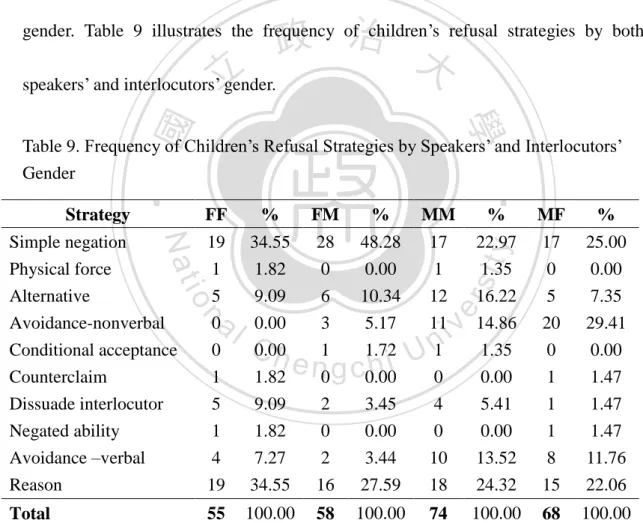

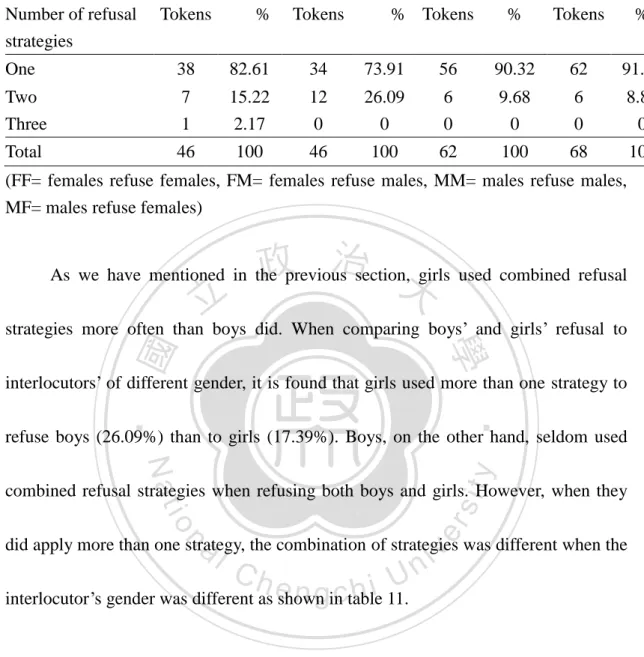

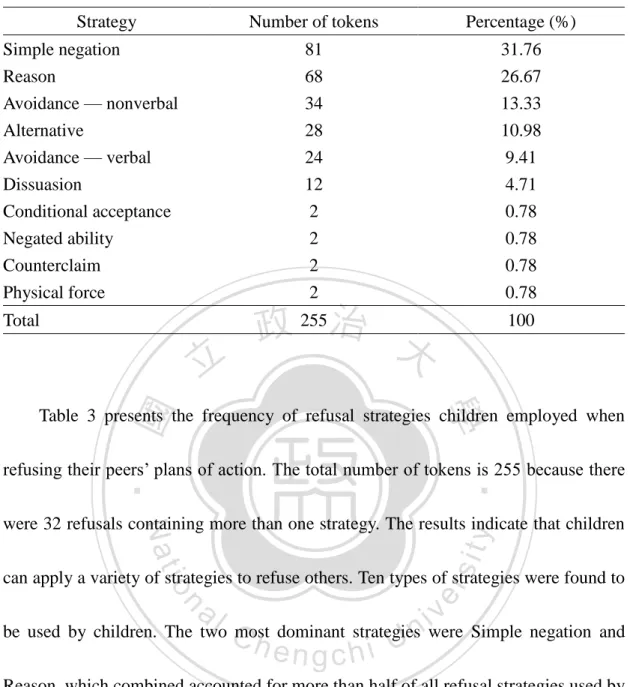

(7) List of Tables. Table 1. Subjects’ gender and age at recording ..................................................... 25 Table 2. Frequency of direct and indirect strategies .............................................. 31 Table 3. Frequency of refusal strategies ................................................................ 32 Table 4. Frequency of the number of refusal strategies in one response............... 44 Table 5. Frequency of the different combination of strategies .............................. 45 Table 6. Frequency of refusal strategies by speakers’ gender ............................... 47 Table 7. The frequency of the use of simple negation combined with other strategies by speakers’ gender .................................................................................. 48 Table 8. Frequency of the number of refusal strategies in one response by speakers’ gender ....................................................................................................... 50. 治 政 Table 9. Frequency of Children’s Refusal Strategies by大 Speakers’ and Interlocutors’ 立 Gender ...................................................................................................... 51 ‧ 國. 學. Table 10. Frequency of the number of refusal strategies in one response by speakers’ and interlocutos’ gender ........................................................................... 56. ‧. Table 11. Frequency of the different combination of strategies by speakers’ and interlocutors’ gender ................................................................................ 57. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i n U. v.

(8) 國 立 政 治 大 學 研 究 所 碩 士 論 文 提 要. 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:兒童在同儕對話中的拒絕策略 指導教授:黃瓊之. 博士. 研究生:鍾易儒 論文題要內容:. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 本研究旨在探討孩童在同儕對話中所使用的拒絕策略,以及說話者及聽者的 性別對於拒絕策略選擇之影響。研究語料來自兩人或三人一組的孩童在玩耍時的 對話,孩童的年紀在四歲七個月到五歲十個月之間。本研究主要採用 Beebe 等人 所提供的拒絕策略分類,研究結果發現,孩童在同儕對話中使用較多的間接拒絕 策略(70%),這也顯示出孩童避免與同儕產生正面衝突,並且努力維護彼此間的 友誼。在所有策略中,孩童最常使用的是簡單否定(simple negation: 31.8%). y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 以及提供理由(reason: 26.7%);此外,在這個年紀的孩童在一次拒絕中,大多 只使用一種拒絕策略。 而在性別的影響方面,則發現在同性別的互動中,女生比男生使用了更多的 直接拒絕策略;此外,與在同性別互動中的表現相比,女生在不同性別的互動中 變得更直接,而男生則變得較委婉。研究也發現,孩童會根據不同性別選擇特定 的拒絕策略,例如,男生較常對女生使用非語言性的迴避策略(nonverbal avoidance)。本研究中討論了造成此現象可能的原因,像是中國文化中女人的角 色、家長對不同性別孩童的教育方式,和不同性別的孩童之間友誼的強弱等等。 總而言之,研究發現不論是說話者的性別或者聽者的性別都會對拒絕策略的選擇. Ch. engchi. 造成一定的影響。. viii. i n U. v.

(9) Abstract. This study aims to explore children’s refusal performance in peer talk and how speakers’ and interlocutors’ genders influence their choice of refusal strategies. The natural conversations produced by dyads of triads of children aged from 4;7 to 5;10 were used for analysis. The refusal strategies adopted in this study are mainly based on Beebe et al. (1990)’s category. The results showed that children applied much more indirect refusal strategies (70%) than direct ones (30%) when refusing their peers,. 政 治 大 their friendship. Among the strategies, children tended to employ simple negation 立. which indicates that they tried to avoid confrontation and make efforts to maintain. only one refusal strategy in a refusal most of the time.. 學. ‧ 國. (31.8%) and reason (26.7%) most frequently. In addition, children at this age applied. ‧. As for the influence of gender, it is observed that in same-gender interactions,. sit. y. Nat. girls used more direct strategies than boys. In addition, in cross-gender interactions,. io. er. girls became more direct while boys were more indirect than in same-gender interaction. Moreover, children tended to choose certain strategy when refusing others. al. n. v i n of different gender; for example,Cboys used a lot moreU h e n g c h i nonverbal avoidance when. refusing girls than boys. Possible reasons such as women’s role in Chinese culture, children’s intensity of friendship between different gender, and parent’s educational style were discussed in the study in order to explain the gender differences. The findings, therefore, suggest that both speakers’ and interlocutors’ genders play an important role in children’s choice of refusal strategies.. ix.

(10) 1. Chapter 1 Introduction. 1.1 Background and motivation Language plays an important role in human social interaction. It is through language that we communicate with others and perform a variety of social activities.. 政 治 大. In order to become members of society, children need to learn not only how to speak a. 立. language but also how to use it appropriately in a multiplicity of social situations. In. ‧ 國. 學. other words, language development is not limited to the acquisition of phonology,. ‧. syntax, and semantics of a language. Children must also acquire communicative. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. language use.. y. competence (Hymes, 1972), which requires knowledge of the social rules for. Ch. engchi. The speech act theory is one of the major. iv n theories U that. underlies work in. communicative competence. Austin (1975) and Searle (1969) claimed that when we use language, we are also performing certain acts. Among all the speech acts, request has been the most commonly discussed, both in adult and child speech. However, other speech acts, such as refusal, have received less attention, especially in child speech. Refusal is a speech act which requires a high level of pragmatic competence to.

(11) 2. be performed successfully (Beebe, Takahashi, & Uliss-Weltz, 1990). It is a potentially face-threatening and impolite act. Therefore, in order to minimize offending the hearer, a variety of refusal strategies are used, including extended negotiation, and indirect strategies. Children need to have the ability to take others’ feelings into consideration and to understand the principles of politeness in order to choose the most appropriate strategy in a given situation. The ability to refuse appropriately can be very important. 政 治 大. to children, especially when they interact with their peers since inappropriate. 立. strategies may affect their friendships. Thus, investigations into children’s refusal. ‧ 國. 學. strategies in peer interactions could help illuminate the development of children’s. ‧. communicative competence.. Nat. io. sit. y. Most studies on refusal have examined the refusal production in adult speech. al. er. (Wang, 2001; Liao, 1994) or in cross-cultural comparison (Liao and Bresnahan, 1996).. n. v i n C studies Although there have been some on Taiwanese children’s refusal h e nconducted gchi U production (Yang, 2003; Yang, 2004), the data was collected through questionnaires or under contrived experiments such as using puppets or watching cartoons. The results may not be spontaneous or natural enough to reveal the children’s refusal. strategies that occur in genuine interactions with others. In genuine interactions, not only verbal strategies but also nonverbal strategies are used to express refusal. Natural conversational data gives us a chance to examine those nonverbal refusals. In addition,.

(12) 3. how children negotiate with others in refusal sequences can only be observed in natural data as well. Some previous studies related to conflict talk valued the importance of natural data and examined children’s conflict talk in natural conversations (Farris 2000; Eisenberg and Garvey, 1981). Conflict talk is by definition a sequence that begins with an opposition, which includes refusals, disagreements, denials, and objections.. 政 治 大. However, not being treated as the focus of those studies, refusal strategies that. 立. children applied were not fully examined and discussed. Most studies only roughly. ‧ 國. 學. categorized negating responses in several ways or mainly discussed how aggressive. ‧. children were in conflict talks without analyzing the refusal strategies carefully.. Nat. sit. al. er. io. production.. y. Therefore, studies are still needed to get the whole picture of children’s refusal. n. v i n C hvariables. Hence, aUnumber of previous studies on Refusal is sensitive to social engchi. children’s refusal production have investigated the influence of social variables such as gender or social status on refusal production. Most studies that explored the effect of gender on children’s refusal only considered the subjects’ gender. However, the influence of the interlocutors’ gender on children’s refusal production has seldom been discussed. Accordingly, in order to obtain a better understanding of the influence of gender, the effect of both the subjects’ and the interlocutors’ gender on children’s.

(13) 4. refusal production should be investigated at the same time.. 1.2 Purposes of the Study In order to 補足 the inadequacy of the previous studies, the present study aims to examine children’s refusal strategies in peer interaction by using natural data. The interactions between children aged 4;7 to 5;10 and their peers were recorded for analysis. In addition, the refusers’ and their interlocutors’ gender are both examined in order to understand the influence of gender on children’s refusal strategies.. 1.3 Research questions. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Based on the purposes of the study, the research questions are as follows:. ‧. What refusal strategies do children employ when talking with their friends?. 2.. Are there gender differences in children’s refusal strategies? Do the speaker’s. io. sit. y. Nat. 1.. n. al. er. and interlocutor’s gender influence the choice of refusal strategy?. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(14) 5. Chapter 2 Literature Review. This chapter will review previous studies related to children’s refusal. First, some investigations on adults’ refusals will be introduced in 2.1. Second, we will focus on the research on children’s refusals in 2.2. Finally, the findings related to refusal and gender will be presented in 2.3.. 立. 2.1 Adults’ refusal. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Refusals in adult speech have been widely discussed in previous studies. Because. ‧. of the possibility of offending the interlocutor, refusal can be a tricky speech act to. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. perform (Kwon, 2004). Failure to refuse appropriately may jeopardize the. i n U. v. interpersonal relations of the speakers. Therefore, various strategies are used to. Ch. engchi. minimize or avoid offense. Different strategies have been explored in many studies. In addition, social variables such as gender and the relative social status of the interlocutor and the refuser were found to be significant variables that affected the choice of refusal strategies. Chen, Ye, and Zhang (1995) identified two types of refusals – substantive and ritual refusals. The former is a refusal that really means “no” and expresses the speaker’s intention not to comply with the interlocutor’s proposed action plan. The.

(15) 6. latter is a refusal that takes place in response to an initiating commissive-directive act, such as an offer or an invitation. Substantive refusals are what we are concerned with in our study. Since our study focused on children’s refusals toward requests, ritual refuses are not included in our data. In the study examining the substantive refusals, the refusal strategies that subjects employed and the influence of four types of initiating acts (requests, suggestions, invitations, and offers), social status and social. 政 治 大. distance between the interlocutor and speaker were examined. Data were collected by. 立. means of a 16-item Production Questionnaire answered by fifty male and fifty female. ‧ 國. 學. native Chinese speakers from the People’s Republic of China. The study adapted the. ‧. coding system proposed by Beebe et al. (1990). The results showed that giving a. Nat. io. sit. y. reason was the most frequently used refusal strategy in Chinese (32.6%). In addition,. al. er. the reasons speakers provided often referred to prior commitments or obligations. n. v i n C hsecond most frequently beyond the speakers’ control. The e n g c h i U used strategy was offering an alternative, followed by direct refusal, then regret, and finally dissuasion. The. impact of the type of initiating act on strategy choice was identified in the study. For example, giving a reason was the most preferred refusal strategy in response to requests, suggestions, and invitations, but not to offers. In response to requests and suggestions, offering an alternative was the second most preferred strategy. However, when refusing invitations and offers, direct refusals were favored. The authors also.

(16) 7. discovered that the refuser’s social status relative to the interlocutor was another factor affecting the choice of refusal strategies. While giving reasons was the preferred strategy in all status relationships, its use increased as the speaker’s social status decreased. Finally, the researchers noted that refusal strategies typically occur in combination and that the most preferred sequence for refusing in Chinese was giving a reason along with an alternative.. 政 治 大. There have also been many studies exploring the influence of culture in refusal. 立. production. Beebe, Takahashi, and Robin (1990) compared the refusal production of. ‧ 國. 學. Japanese learners of English with native speakers of English and Japanese to show the. ‧. pragmatic transfer in refusals. Sixty subjects — 20 Americans speaking English (AEs),. Nat. io. sit. y. 20 Japanese speaking English (JEs), and 20 Japanese speaking Japanese (JJs) — were. al. er. asked to fill out the Discourse Completion Test, which elicits refusals in different. n. v i n initiating acts, namely requests,C invitations, and suggestions. The data provided h e n goffers, chi U the evidence of negative transfer in three areas: the order of semantic formulas, the frequency of semantic formulas, and the content of semantic formulas. In terms of the order of semantic formulas, JJs and JEs have a similar order while AEs formed a different order. For example, in refusing requests with people of lower status, both JJs and JEs made an apology first while AEs did this only with equals. In terms of the frequency of semantic formulas, more than 85 percent of JJs’ and JEs’ refusals.

(17) 8. contained an apology. However, only 40 percent of AEs used an apology as a part of their refusal. The content of the semantic formulas also proved the existence of pragmatic transfer. Finally, from the data collected, it was found that the JJ refusals sounded more formal than AE refusals because of the frequent use of performative verbs and statements of principle and philosophy. In their study, a detailed classification of refusal strategies is provided to analysis adults’ refusal. The. 政 治 大. classification is then adapted by many other studies related to refusal. This refusal. 立. 學. framework we used for analyzing. Wang. (2001). investigated. the. refusals. produced. ‧. ‧ 國. category also fits most of the data we collected; therefore, it is adapted as the major. by. English-. and. Nat. io. sit. y. Chinese-speaking people and the influence of social variables (social distance and. al. er. social power) on refusal production. The refusal data were collected by the Discourse. n. v i n Completion Test. Based on theC analysis by Blum-Kulka (1984, 1989) and h e nproposed gchi U Wood & Kroger (1994), a refusal is divided into three aspects: a central speech act, an auxiliary speech act, and a microunit. The coding system for central speech acts was adopted by Beebe et al. (1990). If more than two utterances occur in a refusal, the second one was identified as an auxiliary speech act. In addition to the strategies proposed by Beebe et al. (1990), four other auxiliary speech acts were pointed out in the study, namely gratitude, positive opinions, empathy, and repetition. Three kinds of.

(18) 9. microunits were also identified from the data as shown below: (1) Address form: title/role, first name, term of endearment, etc. (2) Indicative marker: indication of who the refuser is (3) Syntactic structure: passive and active voice, transferred negation, interrogative, etc. (4) Lexical items: downgraders, understaters, hedges, hesitation markers,. 政 治 大. subjectivizers, upgraders, etc.. 立. The results were consistent with Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory that. ‧ 國. 學. refusal that is more indirect is more polite. However, not all indirect refusals are polite.. ‧. For example, the strategy of avoidance is indirect but at the same time considered. Nat. io. sit. y. impolite. In addition, the results suggested that social factors play an important role in. al. er. refusals; however, the influences were different in different languages. Finally,. n. v i n C h prefer indirectU refusals, Chinese were more although both Chinese and Americans engchi indirect than Americans. From the previous studies related to adults’ refusals, we learn that in order to minimize the threat of causing the hearer to lose face, the refuser may apply a variety of strategies. Different kinds of indirect strategies were preferred when refusing. The combination of strategies and adjuncts was also used to achieve the goal of preserving the other’s face. Moreover, although people tend to strive for politeness when refusing,.

(19) 10. differences in culture and social factors still affect their choice of refusal strategies.. 2.2 Children’s refusal. Children’s refusal can be explored in the literature of conflict talk. Conflict talk is also termed “disputes” (Slomkowski and Dunn, 1992), “adversative episodes,” (Eisenberg and Garvey, 1981) or “arguments” (Dunn, 1996; Maynard, 1985). Conflict is defined as a sequence that begins with an opposition to a request for action, an. 治 政 dissipation of the conflict. The assertion, or an action and ends with a resolution or 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. oppositions include refusals, disagreements, denials, and objections (Eisenberg and Garvey, 1981). Since refusals are one of the elements in conflict talk, a review of. ‧. studies on conflict talk is necessary.. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Many researchers have explored the conflict talk between children and their. i n U. v. peers. Eisenberg and Garvey’s study (1981) was based on the analysis of videotapes. Ch. engchi. of peer interaction among preschool children. Conflict talks produced by a total of 88 same- and mixed-gender dyads of 2- to 5-years-olds were examined. An analysis of the episodes showed that children encode their negating response in five ways as follows: (1) Using a simple negation (e.g. “No” or “Uh-uh”) (2) Supplying a related reason or justification, with or without an explicit negative.

(20) 11. (3) Making a countering move such as proposing an alternative or a substitution for the desired object (4) Temporizing, such as postponing compliance or agreement (5) Evading or hedging by addressing the propositional content of the antecedent The results showed that among these strategies, children used reasons in their initial opposition most frequently (approximately 50% of the time), followed by. 政 治 大. simple negation, countering, temporizing, and evasion. Eisenberg and Garvey also. 立. investigated the strategies used following initial opposition. The results indicated that. ‧ 國. 學. when children applied “adaptive” strategies, namely, the strategies that take into. ‧. Nat. io. sit. or giving reasons, they are most likely to reach a resolution.. y. account the perspective of both participants in the interaction, such as compromising. al. er. Conflict between children and their parents has also been widely investigated.. n. v i n Dunn and Munn (1987) studiedC children’s of justification in dispute with h e n development gchi U their mothers and siblings at 18, 24, and 36 months of age. Children used justifications in about one third of their disputes with both mother and sibling by 36 months, chiefly in terms of their own feelings, but also in terms of social rules and the material consequences of actions. Moreover, children’s emotional behavior and use of justification differed according to the topic of the dispute. Other research conducted by Eisenberg (1992) examined the conflicts between.

(21) 12. mothers and their 4-year-old children. Eisenberg’s study provided descriptive information about what mothers and children argued about, what types of speech acts were opposed, when they use justifications, what kind of initial opposition they used, and what kind of outcome they usually achieved. The results revealed that conflicts involving noncompliance included more justifications. In addition, children seemed to understand the social rule regarding the necessity of providing justification when. 政 治 大. opposing. They were less likely to pursue their position when mothers provided. 立. reasons or alternatives than when mothers used only unelaborated opposition.. ‧ 國. 學. Cultural differences in negotiation styles and topics of conflict were reported in. ‧. previous studies about children’s conflict talk. Tardif (1997) compared the literature. Nat. io. sit. y. on the conflict between Beijing toddlers (M = 22 months) and their mothers with the. al. er. conflict between English-speaking children and their mothers. The results indicated. n. v i n C has the strategies applied that the topics of conflict as well e n g c h i U by mothers and children. were different in these two cultures. For example, Mandarin-speaking children were more likely to use the strategy of not responding or ignoring their caregivers’ requests than they were to refuse or disobey. Recently, a number of studies examined children’s production of refusals explicitly as a speech act. Children started to refuse at a very young age. Refusing allows children to exercise more control over their social environment (Wenar, 1982)..

(22) 13. On the one hand, children use refusals to resist what they dislike. On the other hand, they use refusals to choose what they want. The ability to refuse increased as children got older, and they learned refusal strategies by observing people around them, including parents, teachers, peers, and strangers (Liao, 1994). Guidetti (2000) analyzed the gestural and verbal forms of agreement and refusal messages in young French children aged 21 to 27 months to see whether they varied. 政 治 大. with the age and type of speech act (assertive or directive). Agreements and refusals. 立. were elicited by asking children two kinds of questions: assertives (“Is it an X?”) and. ‧ 國. 學. directives (“Should I give you the X?”). The children’s responses were classified into. ‧. four categories: expected responses (correct ones), opposite responses (incorrect ones),. Nat. io. sit. y. other responses (correct but unconventional), and nonresponses. Refusals may be. al. er. presented in three forms: gestural, verbal, and combined gestural-verbal. The results. n. v i n showed that the older childrenCmore h eoften h i U as expected, even when the n g cresponded difference between the two age groups was only six months. In addition, children used more verbal responses than the other two forms, especially when making refusals. Several studies have investigated refusals produced by children in Taiwan. Guo (2001) conducted a case study to observe the pragmatic development of a. Taiwanese-speaking boy from age 1;11 to 2;10. Requests, refusals, and turn-taking in.

(23) 14. the conversation between the child and adults were examined in her study. From the data collected, refusals produced by the child were classified into five categories: direct refusals (without any explanation), reasons, changing the topic, a combination of direct refusal and a reason, and a combination of direct refusal and changing the topic. The findings revealed that the child used direct refusals most frequently (74%), which suggested that he did not usually consider the refusee’s face when refusing; he. 政 治 大. simply expressed his unwillingness. The child sometimes used both verbal and. 立. nonverbal expressions such as shaking his head to show refusal. Moreover, when the. ‧ 國. 學. child’s refusals were turned down by adults again and again, he tended to abandon. ‧. verbal expressions and use different actions such as crying or hitting in an effort to. Nat. io. sit. y. make adults accept his refusals. Wu (2010) examined the refusals produced by one. al. er. Mandarin-speaking boy from age 2;7 to 3;7 in mother-and-child conversations. The. n. v i n C hstrategies developed findings revealed that his refusal e n g c h i U with age. His use of direct. refusals decreased as he grew older. It was also observed that his ability to take others’ perspectives into account increased over time. Some studies discussed the refusal production in older children. Liao (1994) conducted several experiments to investigate children’s communicative competence in refusing. First, she examined the children’s understanding of tautologous construction, such as 好是好 ‘good is good’, in refusals. Elementary school children aged seven to.

(24) 15. eleven years old were asked to fill out the Discourse Completion Test (DCT), which includes items of tautology. The results indicated that eight-year-old children are able to understand this complex construction. In addition, from the answers children provided in the DCT, it was found that at the age of 13, girls used the strategy of putting the blame on the third party more often than boys did. Liao also asked children to rank the politeness of four utterances of offering alternatives as refusal.. 政 治 大. The rankings given by children of eight years old or older were consistent with those. 立. given by adults. Therefore, they were as good as adults in judging the relative. ‧ 國. 學. politeness of utterances. In another experiment, Liao compared the strategies. ‧. elementary school children, junior high school students, and adults used when. Nat. io. sit. y. refusing the utterance, “Go to the office to get the compositions and bring them back. al. er. to the class.” The results showed that most elementary school children and adults used. n. v i n C h or explaining. U lying, making excuses, giving reasons, e n g c h i Furthermore, significantly more elementary school children than adults used composite strategies. Yang (2003) investigated the refusal production and perception of children and the influence of social factors such as gender and social status on refusal production and politeness perception. One hundred and eighty Mandarin-speaking subjects of kindergarten and elementary ages were chosen for the study. Sections of cartoons that included invitations and requests were shown to the subjects to elicit their refusals..

(25) 16. Each speech act included three social statuses of the refuser relative to the refusee: low, equal, and high. Results indicated that age had a great influence on refusal production. Older children produced more strategies and more words when refusing. Children also generated more indirect refusals and reasons as they got older. In addition, the children’s refusal production was influenced by sociolinguistic background and gender. Children from lower social class families performed better. 政 治 大. than children from higher social class families and applied more refusal strategies.. 立. Female children produced more words in refusal responses and used alternatives,. ‧ 國. 學. adjuncts, and avoidance more than male children. Yang also observed that children are. ‧. aware of social status and the power that goes along with it. Children applied different. Nat. io. sit. y. refusal strategies when they were of a different social status relative to the addressee.. al. er. Yang (2004) conducted similar research to investigate the interactions between. n. v i n C h and IQ) and children’s individual factors (gender, popularity, refusals. Refusals were engchi U obtained by asking 201 fifth graders to finish the Discourse Completion Test. The influences of gender, popularity, and IQ on refusal strategies were reported in her study. Girls were more polite than boys when refusing others. More popular students seemed to focus more on relationships of equal ranking than less popular students did. They tended to be polite to people of equal status. Students with higher IQs tended to use more words and the strategy of “negated ability” in their refusals compared to.

(26) 17. students with lower IQs. Therefore, the author suggested that teachers should encourage less popular and lower-IQ students to show more politeness in their refusals in order to improve their personal relationships. Both the literature concerning children’s conflict talk and refusals provide us some knowledge about children’s refusal production. Previous studies have investigated children of different age groups, from one year old to elementary school. 政 治 大. age. The results showed that children’s refusal strategies become more complex and. 立. indirect when children grow older. Children shift from mainly rely on simple negation. ‧ 國. 學. to various indirect strategies such as reason, alternatives, or postponement, etc.. ‧. Besides, children’s refusal is found to be sensitive to social factors such as gender or. Nat. io. sit. y. social status. Although several studies have been conducted to examine the refusal. al. er. production by Mandarin-speaking children, the data collection method – using. n. v i n C h refusals – is limiting cartoons or questionnaires to elicit e n g c h i U and may bias the results. Since the situations were not authentic, the results may not accurately reflect children’s real-life performance in making refusals.. 2.3 Refusal and gender. As mentioned previously, research on conflict talk and refusal are closely related. In many studies related to refusals or conflict talk among children, it was found that boys and girls perform differently. Farris (2000) analyzed the cross-sex peer conflict.

(27) 18. in a Mandarin Chinese-speaking preschool in Taiwan. There were four classes in the preschool: Youyouban, Xiaoban, Zhongban, and Daban. The children were aged from 2;6 to 6;6, with Youyouban having the youngest children, followed by Xiaoban, Zhongban, and finally Daban. The naturally occurring conversations in each class were videotaped for analysis. The results showed that conflict occurs as frequently in cross-sex interaction as in boy-boy interaction. Moreover, Chinese girls also used the. 政 治 大. “aggravated” style of conflict talk in the cross-sex conflict, which is associated in the. 立. literature with a masculine sex-typed style. The author believed that this kind of. ‧ 國. 學. subversion showed that Chinese girls were trying to attain a new position in the. ‧. rapidly changing society of modern Taiwan in which females have more autonomy. Nat. io. sit. y. and power. From the cross-sex peer conflict, it was also found that certain children. al. er. identified as peer leaders were doing the borderwork to establish gender boundaries.. n. v i n Therefore, the author argued inCthe one way of constructing gender is via h eendnthat gchi U cross-sex conflicts. Yang (2003) investigated the influence of age, gender, and sociolinguistic background on preschool and elementary school children’s refusal strategies. In terms. of gender, the results revealed that female children generated more words when refusing. In addition, they applied more strategies and more indirect refusals than male children. They used more instances of alternatives, avoidance, and adjuncts than.

(28) 19. male children. The author concluded that female children had better refusal skills and that they are more polite than male children. Similar results were found in Yang’s (2004) research on elementary school children’s refusal production. It was found that compared with boys, girls favor showing politeness in refusing people of all kinds of social rankings. Some studies examined the influence of culture on gender differences. Kyratzis. 政 治 大. and Guo (2001) analyzed the conflict talk of American children and that of Chinese. 立. children from China. They used their results to argue against the separate world. ‧ 國. 學. hypothesis. The Separate World Hypothesis (Maltz & Borker, 1982) states that as the. ‧. result of separated peer play in childhood in which girls play predominately with. Nat. io. sit. y. other girls and boys play with other boys, the two genders develop different. al. er. communicative styles. Boys also seem to speak more directly and forcefully, they are. n. v i n C h and they are more more likely to focus on themselves, e n g c h i U assertive. Kyratzis and Guo pointed out that although research on American children supported the separate world hypothesis, the research with Chinese children had challenged the view of girls’ language as cooperative. The results showed that in same-sex talk, American boys and Chinese girls used the most direct strategies, including third party compliant and censures and aggravated commands. American girls used the most mitigated strategies, and Chinese boys used a combination of direct and indirect strategies. The authors.

(29) 20. provided some possible explanations for the results. One was that Chinese females use more assertive strategies because they are licensed to be powerful in certain contexts, such as in the discussion of moral norms. Another possibility is explained by the differences in the ways groups are formed and maintained in peer interaction. In China, the group boundary is more solid since “interdependent construal of the self” is culturally valued. Chinese girls can afford more direct and aggravated strategies, and. 政 治 大. Chinese boys do not need a hierarchical group structure; therefore, they used more. 立. mitigated conflict strategies. In cross-sex conflicts, the results indicated contextual. ‧ 國. 學. complexity in the use of conflict strategies in both cultures. Both the theme of the. ‧. interaction and the boy-girl ratio influence children’s choice of strategies.. Nat. io. sit. y. As observed in the previous studies, gender is an important factor that. al. er. influences children’s choice of refusal strategies and their conflict talk. It is found that. n. v i n C h refusal strategies.UHowever, the results found in boys and girls tend to use different engchi the previous studies were not consistent. Some suggested that girls used more indirect strategies than boys while some discovered that girls used more direct strategies. The difference in methodology, for example, the way data was collected, may cause the difference. In addition, the literature revealed that culture is also an important issue when discussing gender differences. Therefore, in our study, instead of using questionnaires to obtain data, we used natural conversations to analyze children’s.

(30) 21. refusal production. We aim to discover how speaker’s and interlocutor’s gender influence children’s choice of refusal strategies and find out if our results confirm or contradict the previous findings.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(31) 22. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(32) 23. Chapter 3 Methodology. 3.1 Subjects and data. The subjects of this study were preschoolers aged 4;7 to 5;10 (mean: 5;4). The children in this age range were chosen because previously studies suggested that. 治 政 children learned the rules for friendly interaction from 大their peers during the time 立 ‧ 國. 學. period, approximately from age 5 to 15. In addition, many previous studies related to children’s conflict talk or refusals have examined children within this age period and. ‧. various strategies were found to be used by children (Eisenberg and Garvey, 1981;. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Wang, 2007). Therefore, choosing children in this age range should help us to. i n U. v. discover various refusal strategies and how they use these strategies to show. Ch. engchi. unwillingness and keep a friendly interaction at the same time. There were two sets of data in our study. Some were collected in Wanxing Kindergarten in Taipei. The students in Wanxing Kindergarten were divided into two mixed-age classes. Three girls and three boys were chosen from one of the classes to be videotaped. These children knew each other well and often played together. They all came from middle class families, and their parents had high educational backgrounds with university or advanced degrees. Children were divided into same-.

(33) 24. and mixed-gender dyads and triads. During the play time in the kindergarten, one of the groups was asked to play freely in a spare classroom full of different toys. The interaction between children was videotaped. The length of the data collected each time varied from 15 to 30 minutes, depending on how the children interacted. The total length of the conversations equals about seven hours. The other data were collected in a daycare center in Taipei. The subjects were. 政 治 大. two girls and one boy. They also knew each other well. The interactions between. 立. these children were videotaped. As with the children in Wanxing Kindergarten, they. ‧ 國. 學. were playing with toys most of the time during the observation. The length of the data. ‧. varied from 30 to 60 minutes. The total length of the data is approximately four hours.. Nat. io. sit. y. Because of the similarity in the subjects’ ages, their relationships, and the. al. v i n C hdid not interfere U observer e n g c h i with the. n When videotaping, the. er. activities taking place during videotaping, both sets of data were used for analysis. children’s interaction.. Therefore, the data collected is quite natural. Spontaneous speech to be examined in this study belongs to the Language Acquisition Lab of the Graduate Institute of Linguistics of NCCU, directed by Dr. Chiung-chih Huang..

(34) 25. The information about subjects is provided in table 1. Table 1. Subjects’ gender and age at recording Subject. Gender. Age at recording. LIN. Girl. 5;7. ZHI. Girl. 5;0. ANN. Girl. 5;10. SAL. Girl. 5;7. DOR. Girl. 4;7. JUN. Boy. 5;2. NIN. Boy. 5;2. Boy 治 政 Boy 大. CAI SHI. 立. 5;6. ‧ 國. 學. 3.2 Procedures of data analysis. 5;7. ‧. The data collected were first transcribed in the CHAT (Codes for the Human. sit. y. Nat. Analysis of Transcriptions) format. Refusals in the data were then identified. A refusal. n. al. er. io. is a responding act in which the speaker refuses to engage in an action proposed by. Ch. i n U. v. the interlocutor. Although the initiating acts being refused include requests, invitations,. engchi. offers, and suggestions, only refusals responding to requests were examined in this study. After identifying the refusals, the refusals were further coded according to the refusal categories listed in 3.3. When a refusal contained more than one strategy, each strategy was counted separately. Therefore, the number of refusal strategy tokens is more than the number of refusals. After the data were all coded, about one fourth of the data were coded by another.

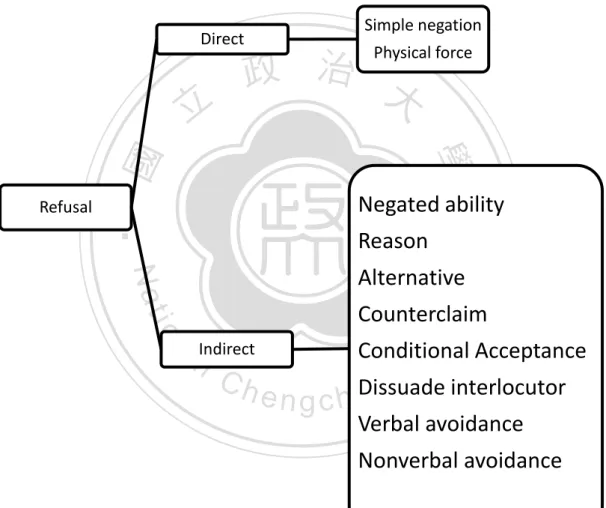

(35) 26. coder who is familiarized with the coding system. The inter-rater reliability was then evaluated with the Cohen’s kappa value. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient indicates that the inter-rater reliability is very high (k= 0.88).. 3.3 Coding categories. The coding categories proposed by Beebe et al. (1990) were adapted for data analysis. Some refusal strategies that never appeared in children’s data were omitted,. 治 政 and some other strategies were added to better fit the data. 大The strategies are classified 立 ‧ 國. 學. into two categories: direct and indirect. The direct refusal includes simple negation and physical force. The indirect refusal strategies are citing negated ability, giving. ‧. reasons, offering alternatives, dissuading the interlocutor, making counterclaims,. sit. y. Nat. io A. Simple negation. al. n. defined below:. er. conditional acceptance, verbal avoidance, and nonverbal avoidance. The strategies are. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Simple negation means that children use direct denial of compliance without reservation. The most commonly used lexical items are 不要 buyao ‘no’ or 不行 buxing ‘no’. B. Physical force Children do not only refuse verbally. They sometimes appeal to physical force such as grabbing or hitting to show noncompliance..

(36) 27. C. Negated ability This refers to utterances that show inability to comply with the interlocutor’s request. Utterances such as 我不會送(餐) wo buhui song(can) ‘I can’t deliver (the meal)’ belong in this category. D. Reason This refers to the explanations or justifications given by the speaker for. 政 治 大. noncompliance. Examples like 這是我的 zhe shi wode ‘This is mine’ or 我不喜歡送. 立. 信 wo bu xihuan song xin ‘I don’t like to deliver a mail’ are included in this category.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. E. Alternative. Alternative refers to the utterances suggesting a different course of action.. Nat. io. sit. y. Utterances such as 大家一起(做) dajia yiqi “Let’s do it togother” after the request 你. al. er. 做軌道 ni zuo guidao ‘you build the track’ are classified as alternatives. The refuser. n. v i n C h an alternative related shows noncompliance by suggesting e n g c h i U to the request. F. Counterclaim. A counterclaim happens when the speaker refuses the request by repeating the interlocutor’s plan of action as the speaker’s own plan of action. For example, when a requester wanted a certain toy and made a request 給我 gei wo “Give it to me,” the refuser used the same utterance 給我 gei wo “Give it to me” as his own request in order to show noncompliance..

(37) 28. G. Conditional acceptance This refers to the utterances which indicate that the refusee’s plan of action will be accepted under certain conditions. For instance, when the child asked for a block, the refuser responded 那你還我一個 na ni huan wo yige “Then you have to give me one back” to indicate that the request would not be accepted until the condition was met. H. Dissuade interlocutor. 政 治 大. This type of refusal attempts to persuade the refusee to give up his or her action. 立. plan. Threats or statements of negative consequences, guilt trips (pointing out things. ‧ 國. 學. the refusee failed to do in the past), criticizing, and asking for rewards are methods. ‧. the refuser employs to dissuade the interlocutor. For example, when one child said. Nat. io. sit. y. that he wanted to ride the horse, the refuser responded 你騙人 ni pian ren ‘You lied. al. er. to me’ because the requester had promised that he would not touch the toy horse. The. n. v i n Chopes refuser criticized the requester in him to give up the request. h e ofn persuading gchi U I. Avoidance — verbal. This refers to utterances that avoid a direct response to a proposed course of action. Postponement such as 等一下 dengyixia “wait a minute” and changing the topic are included in this category. J. Avoidance — nonverbal The speaker sometimes uses nonverbal avoidance as a way of refusing. For.

(38) 29. instance, they may remain silent, concentrate on doing something, or walk away from the interlocutor. No verbal response is provided at all.. Direct. 立. Physical force 治 政 大. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Negated ability Reason. Nat. io. sit. y. Alternative. Counterclaim. er. Refusal. Simple negation. n. Conditional a Indirect v Acceptance i l C U n interlocutor h e n g c h iDissuade Verbal avoidance. Nonverbal avoidance. Figure 1. Framework of refusal analysis.

(39) 30. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(40) 31. Chapter 4 Data Analysis. 4.1 Children’s use of refusal strategies The data show a total of 222 refusals in 11 hours of observation. The frequency of refusals was 20.2 per hour. In terms of directness, children tended to apply indirect. 政 治 大. strategies when refusing others. Table 2 illustrates the frequency of the use of direct. 立. 學. ‧ 國. and indirect refusals.. Table 2. Frequency of direct and indirect strategies Direct/ Indirect strategy. 83 172. 32.55 67.45. 255. n. al. 100. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Total. Percentage (%). ‧. Direct refusal Indirect refusal. Number of tokens. i n U. v. The frequency of the use of indirect refusal strategies is 67.45%, while the use of. Ch. engchi. direct refusal is only 32.55%. The result indicates that children attempted to use indirect strategies to mitigate the threat to interlocutor’s face caused by refusals. In order to understand children’s performance of refusals more thoroughly, the frequency of different refusal strategies was examined, as shown in table 3..

(41) 32. Table 3. Frequency of refusal strategies Strategy. Number of tokens. Percentage (%). Simple negation Reason Avoidance — nonverbal Alternative Avoidance — verbal Dissuasion Conditional acceptance Negated ability. 81 68 34 28 24 12 2 2. 31.76 26.67 13.33 10.98 9.41 4.71 0.78 0.78. Counterclaim Physical force. 2 2. 0.78 0.78. Total. 立. 政 255治 大. 100. ‧ 國. 學. Table 3 presents the frequency of refusal strategies children employed when. ‧. refusing their peers’ plans of action. The total number of tokens is 255 because there. sit. y. Nat. were 32 refusals containing more than one strategy. The results indicate that children. n. al. er. io. can apply a variety of strategies to refuse others. Ten types of strategies were found to. Ch. i n U. v. be used by children. The two most dominant strategies were Simple negation and. engchi. Reason, which combined accounted for more than half of all refusal strategies used by the children. Other strategies such as Verbal and Nonverbal avoidance, Alternatives, Dissuasion, Conditional acceptance, Negated ability, Counterclaim, and Physical force were also used. The qualitative analysis of these refusal strategies is provided in the following sections..

(42) 33. 4.1.1 Simple negation Among the strategies, Simple negation (31.76%) was the most frequently used. The commonly used linguistic forms are buxing and buyao. The following example illustrates how a child uses a direct refusal with his peer: Example 1: JUN and CAI are playing with blocks. 1. . 2.. 借我一個就好了.. JUN:. ‘Just lend me one [block].’ 不行.. CAI:. ‘No.’. 立. 政 治 大. In example 1, JUN asked CAI to lend him one block, and CAI refused him with. ‧ 國. 學. a Simple negation: 不行 buxing ‘No’. Simple negation is the most explicit strategy,. ‧. and thus can be very effective in conveying noncompliance. However, Simple. Nat. io. sit. y. negation is considered impolite since the speaker does nothing to minimize the threat. al. er. to the face of the hearer. Using this kind of direct refusal suggests that the child is. n. v i n Ch focusing on his or her own unwillingness does not take the hearer’s face into e n gand chi U account. 4.1.2 Reason. Aside from Simple negation, the children also refused by giving reasons fairly often (26.67%). Some studies in adults’ interactions suggested that the only way in which a request may be refused with reasonable politeness is to give an account (Goffman, 1976). From the reasons provided by children, we found that some are.

(43) 34. self-oriented while some are nonself-oriented. Self-oriented reasons refer to reasons which mainly demonstrate the speaker’s own needs, feelings, or desires. Example 2 demonstrates how the child used a self-oriented reason to refuse the listener’s request. In example 2, LIN asked NIN to build a house with her. However, NIN refused her with a self-oriented reason that he wanted to build something else — a triangle. In terms of perspective-taking ability, the child seemed to concentrate on his own desire. 政 治 大. and therefore revealed that although he understood the hearer’s need for a reason for. 立. 我們做房屋. ‘Let’s build a house.’ 我要做三角形.. sit. io. ‘I want to build a triangle.’. n. al. er. NIN:. y. Nat. 2.. ‧. Example 2 1. LIN:. 學. viewpoint.. ‧ 國. the refusal, he still cared more about his own desire and thought from his own. i n U. v. By contrast, nonself-oriented reasons refer to social rules, regulations, or others’. Ch. feelings. Consider example 3.. engchi. Example 3 1. JUN:. 我也要玩.. . ‘I want to play, too.’ 這邊只能兩個人玩.. 2.. LIN:. ‘Only two people can play here.’ Instead of stating her own needs or feelings, LIN rationalized her refusal by citing a regulation that only two people were allowed to play in that classroom. Because a regulation is beyond one’s control, providing such a reason implies that the.

(44) 35. speaker is not refusing deliberately. Therefore, the speaker can avoid the risk of causing the hearer to lose face. The results showed that children assumed others have reasons for saying what they say. Therefore, one cannot just say no. A simple no was not accepted by most children as sufficient. The refuser is expected to give an explanation for noncompliance. The reason for failing to comply would be queried if not provided by. 政 治 大. the refuser, as shown in example 4. DOR wanted to watch TV, however, SAL refused. 立. her request with a direct refusal without giving any reason. DOR did not accept her. ‧ 國. 學. refusal and queried about her reasons for noncompliance. After SAL supplied her with. ‧. a reason for refusing, DOR finally accepted it.. y. al. SAL:. ‘I want . . . I want to watch TV.’ 不行.. DOR:. ‘No.’ 為什麼?. SAL:. ‘Why?’ 因為這 [= a toy remote control] 是我的.. n. 2. 3. . 4.. sit. 我想 [/] 我想 <看電視> [>].. er. DOR:. io. 1.. Nat. Example 4. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. ‘Because this [toy remote control] is mine.’ 4.1.3 Nonverbal avoidance Children sometimes use nonverbal avoidance such as remaining silent when refusing. Nonverbal avoidance (13.33%) was commonly used as refusal by children. However, few studies have paid attention to this strategy. The reason lies in the.

(45) 36. different methods of data collection. Previous studies used experiments or questionnaires such as Discourse Completion Test to elicit children’s refusal. Such important strategies never appear under those methods and are thus neglected. Therefore, it is proved that naturally obtained data provide us with a better way to understand children’s authentic refusal performance. In our data, children sometimes ignored the request and kept doing what they are. 政 治 大. doing or even walked away from the requester without giving any response. Example. 立. JUN:. ‘Bring that to me.’ 0 [% 繼續玩玩具].. y. 2.. 那個拿過來.. Nat. . ZHI:. ‧. 1.. 學. Example 5. ‧ 國. 5 illustrates how children used nonverbal avoidance to refuse a request.. n. er. io. al. sit. 0 [% keeps playing with the toy]. i n U. v. In example 5, ZHI asked JUN to bring her the block. ZHI’s request was clear and loud;. Ch. engchi. however, JUN ignored her request. He simply remained silent and kept playing with his toy, hoping that ZHI will give up her request. Remaining silent is considered impolite because it shows no respect to the hearer. It makes the hearer feel that his or her request is not only being refused but even worse, neglected. However, children applied this strategy when they could not think of a better way to refuse the interlocutor. From the data collected, we discovered that this strategy is often used when the request was repeated even though the child had.

(46) 37. previously refused. The refuser chose to keep silent and let the hearer give up the request. 4.1.4 Alternative Children sometimes suggested an alternative proposal to distract the hearer from continuing to pursue his or her original intent (10.98%). According to Chen et al. (1995), alternatives provide a way to avoid a direct confrontation. They also pointed. 政 治 大. out that providing an alternative can preserve the hearer’s face by showing the. 立. speaker’s concern for the hearer’s need. And therefore, alternatives in refusal reflect. ‧ 國. 學. the notion of respectfulness and modesty in the Chinese conception of politeness.. ‧. Example 6 shows how an alternative was used as a refusal.. y. al. NIN:. ‘I found them first.’ 那我們一人一個.. n JUN:. ‘Give me these [blocks].’ 這個是我發現的.. 2. . 3.. Ch. engchi. sit. 這個 [= two blocks] 給我.. er. JUN:. io. 1.. Nat. Example 6. i n U. v. ‘Then we each get one.’ In example 6 JUN wanted to have the two blocks in NIN’s hand. JUN not only used an imperative request but also provided the reason that he found the blocks first. NIN then refused to give back the blocks but tried to negotiate with JUN. NIN proposed an alternative that each of them could have one of the blocks. This example reveals that NIN had the ability of taking another’s needs into consideration. He.

(47) 38. understood that JUN wanted the blocks, and he tried to respond to that desire accordingly. He showed his sincerity and concern for the hearer’s need. In addition, the reason that NIN offered an alternative here may be that JUN had provided him with a reason. NIN realized that it would be difficult to refuse JUN. Therefore, he offered an alternative that could satisfy both speakers; they could each get one block. The refusal then was carried out successfully. 4.1.5 Verbal avoidance. 立. 政 治 大. Children sometimes used verbal avoidance (9.41%) to show refusal. According. ‧ 國. 學. to Chen et al. (1995), any act occurring immediately after an initiating act is taken as a. ‧. meaningful responding act; therefore, avoiding a direct positive response indicates. Nat. io. sit. y. refusal. Although verbal avoidance is an indirect strategy, it can still be perceived as. al. v i n ‘waitCa hminute’ to avoid U e n g c h i confrontation.. n used 等一下 deng yixia. er. being impolite. The most commonly used method is postponement. Children often Other linguistic. forms such as “I have to think about it” were also used by children to postpone compliance, as shown in example 7. Example 7 1. 2. . 3.. LIN:. 你當我哥 # 然後我當你的姐.. LIN:. ‘You’ll be my brother, and I’ll be your sister.’ 這樣可以嗎?. JUN:. ‘Is this OK?’ 我要考慮. ‘I’ll have to think about it.’.

(48) 39. In example 7, LIN asked JUN to pretend to be her brother. Instead of refusing LIN directly, JUN used the postponement “I’ll have to think about it” to avoid direct confrontation. From the results, we discovered that sometimes when children said “wait a minute,” they really meant it; they did fulfill the request afterward. However, most of time, they just used postponement as a way of letting the hearer give up his or her desire.. 政 治 大. Children also used topic switching to refuse the hearer. Example 8 demonstrates. 立. NIN:. ‘Let’s play with this.’ /ei/你看 [% 把玩具丟出去].. y. 2.. 我們玩這個.. Nat. . CAI:. ‧. 1.. 學. Example 8. ‧ 國. how the child tried to change the topic in response to the request.. n. er. io. al. sit. ‘Look!’ [% throwing another toy]. i n U. v. When CAI asked NIN to play with a certain toy together, NIN threw another toy. Ch. engchi. out to distract CAI. In this interaction NIN avoided refusing directly and successfully distracted the hearer from his own request. CAI forgot his request, and they played with the toy that NIN threw. 4.1.6 Dissuade interlocutor There are many ways to dissuade the interlocutor, such as mentioning negative consequences, asking for a reward, or criticizing. Take example 9 for instance. SHI asked SAL to play the game of rolling together. SAL first refused the request directly.

(49) 40. by saying buyao. Then she tried to dissuade SHI by telling him that playing that game is not beneficial to him since the game is not fun. SAL was trying to let SHI know that she refused because she thought that it would be better for SHI to give up on the original plan. Using such a strategy shows that the speaker not only tried to mitigate the threat to the hearer’s face but also expressed consideration for the hearer’s benefit. The speaker shifted the focus of the refusing act from the refuser to the hearer. If SHI. 政 治 大. didn’t want to play a boring game, he would have to play something else.. 立. Example 9. ‧ 國. SAL:. ‘That’s not fun.’ 不好玩啦.. al. n. ‘Not fun.’. Ch. engchi. y. sit er. 4.. SAL:. ‘No.’ 那樣子不好玩.. io. . SAL:. ‘Let’s play the rolling game.’ 不要啦.. Nat. 3.. 我們來玩 # 滾滾遊戲.. ‧. 2.. SHI:. 學. 1.. i n U. v. Besides mentioning a negative consequence of the request, children also used other ways to dissuade the interlocutor, such as criticizing the request or the requester. Consider example 10. Example 10 1.. 2.. NIN:. 我需要電話 [% 拿走地上的玩具電話].. NIN:. ‘I need the phone.’ [% takes away the toy phone that was on the floor] 我需要. ‘I need [it].’.

(50) 41. . 3.. LIN:. /ei -:/你是怎樣阿. ‘What’s wrong with you?’. In example 10, LIN found a toy phone and put it on the floor. NIN asked for the toy phone and before LIN responded to his request, NIN had already taken away the phone. LIN became angry and criticized NIN’s action by saying, “what’s wrong with you.” Unlike the use of dissuasion in example 9, here the criticism was very impolite. This kind of usage often occurred when the requester did something which irritated. 治 政 the requestee, such as taking away something without大 permission or breaking one’s 立 ‧ 國. 學. promise.. 4.1.7 Conditional acceptance. ‧. Only two examples were found in the data that included conditional acceptance. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. (0.78%). This strategy shows that the request could be accepted only under a certain. i n U. v. condition. Example 11 shows how the child used conditional acceptance to refuse the hearer.. Ch. engchi. Example 11 1. . 2.. JUN:. 我需要一個 [= block].. CAI:. ‘I need one [block].’ 那你還我一個 [= block]. ‘Then you have to give me one back.’. In example 11, the children were building cars. JUN asked CAI to give him one block. However, CAI said that only if JUN gave him one block back, he would accept the request. Using conditional acceptance reveals that the speaker understands the.

(51) 42. requester’s need, however, the request is not accepted under the current circumstances. Conditional acceptance also leaves the door open for future compliance.. 4.1.8 Negated ability. Children expressed that they were not able to accomplish the request as a refusal strategy (0.78%). Take Example 12, for instance. The children pretended that they were working in a restaurant. DOR asked SAL to deliver meals to the customer. SAL. 治 政 refused to do it by saying that she didn’t know how to deliver 大 the meals. 立. 2.. DOR:. 你來送餐.. SAL:. ‘You deliver the meals.’ 啊我不會送.. ‧. . ‧ 國. 1.. 學. Example 12. io. sit. y. Nat. ‘Oh, I don’t know how to deliver [the meals].’. al. er. Negating one’s ability to comply with the request indicates that the speaker did. n. v i n C h has to refuse because not refuse deliberately. The speaker e n g c h i U he or she is unable to accomplish the request, even if willing. This kind of strategy expresses the speaker’s concern about the requester’s need and also indicates the speaker’s willingness to help meet the requester’s desire. Negating one’s ability also negates the presupposition underlying the request that the speaker believes the hearer is able to do something. Therefore, applying this strategy can successfully make the requester give up the request..

(52) 43. 4.1.9 Counterclaim When children use counterclaim as a refusal strategy, they not only express their noncompliance but also propose their own request at the same time. Consider example 13. Example 13 1.. . 2.. LIN:. <我要用> [/] 我當挖土機 [% 拿走玩具挖土機].. JUN:. ‘I want to use . . . I will be the digger.’ [% takes away the toy digger] 我當挖土機.. 政 治 大 ‘I will be the digger.’ 立. ‧ 國. 學. In example 13 LIN and JUN both want to take the toy digger. Therefore, when LIN requested it, JUN refused her request by proposing the same request immediately.. ‧. When children are eager to obtain the same thing as the requester, they may not care. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. about the hearer’s needs or make any effort to diminish the threat to the hearer’s face.. i n U. v. This is considered an impolite strategy, and only a few examples (0.78%) were found in our data.. Ch. engchi. 4.1.10 Physical force The results showed that children not only relied on verbal refusals, they sometimes used more aggressive ways to show noncompliance. Physical force (0.78%) was observed when the child who made the request had already taken the object he requested before getting permission, as shown in example 14. The refuser then used physical force — in this case, grabbing to take back the object..

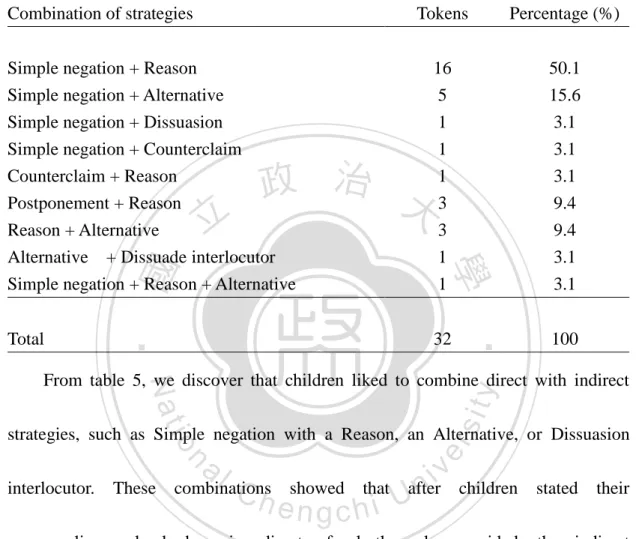

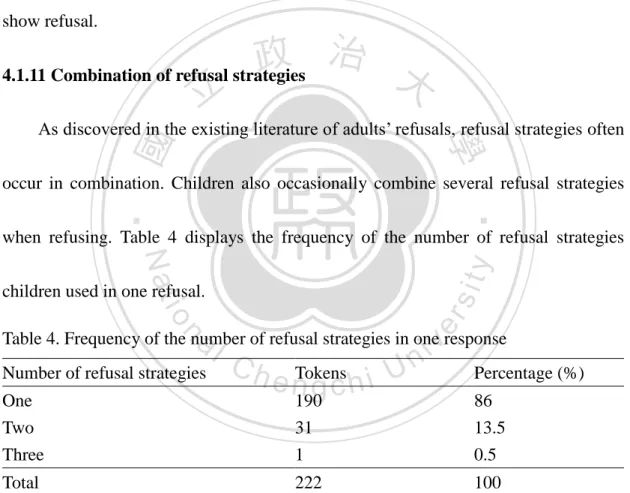

(53) 44. Example 14. . *JUN:. 給我 [% 伸手拿玩具].. *NIN:. ‘Give it to me’ [% reaches for the toy] 0 [% 搶回玩具]. 0 [% grabs the toy back]. However, there were only two refusals in our data in which physical force was used. Children at this age are already capable of using language most of the time to show refusal.. 治 政 4.1.11 Combination of refusal strategies 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. As discovered in the existing literature of adults’ refusals, refusal strategies often occur in combination. Children also occasionally combine several refusal strategies. ‧. when refusing. Table 4 displays the frequency of the number of refusal strategies. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. children used in one refusal.. i n U. v. Table 4. Frequency of the number of refusal strategies in one response Number of refusal strategies One Two Three Total. Ch. e nTokens gchi. Percentage (%). 190 31 1. 86 13.5 0.5. 222. 100. As table 4 shows, children’s refusals tend to be simple and short, which accords with the previous studies (Wu, 2010; Yang, 2003). In our data, children usually applied only one strategy for refusing (86%). However, they sometimes used two (13.5%) or three strategies (0.5%) in one refusal. They combined different kinds of.

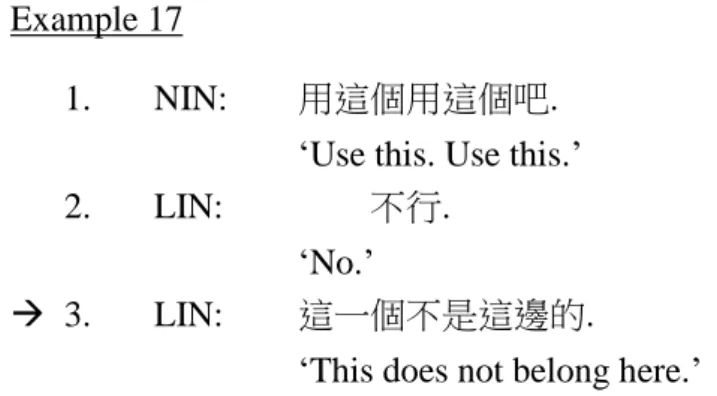

(54) 45. strategies to mitigate the threat to the hearer’s face. Table 5 demonstrates the frequency of the combination of strategies children applied in our data.. Table 5. Frequency of the different combination of strategies Combination of strategies. Tokens. Percentage (%). Simple negation + Reason Simple negation + Alternative. 16 5. 50.1 15.6. Simple negation + Dissuasion Simple negation + Counterclaim Counterclaim + Reason Postponement + Reason. 1 1 1 3. 3.1 3.1 3.1 9.4. Reason + Alternative Alternative + Dissuade interlocutor Simple negation + Reason + Alternative. 3 1 1. 9.4 3.1 3.1. Total. 32. 學 ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. 100. sit. y. Nat. From table 5, we discover that children liked to combine direct with indirect. n. al. er. io. strategies, such as Simple negation with a Reason, an Alternative, or Dissuasion interlocutor.. These. Ch. combinations. showed. that. engchi. i n U. after. v. children. stated. their. noncompliance clearly by using direct refusal, they also provided other indirect strategies to diminish the force brought by direct refusal. Among these combinations, using Simple negation with Reason was the most commonly used combination (50%). Consider example 15. Example 15 1. . 2.. SHI:. 我要跟你換槍.. SAL:. ‘I want to trade guns with you.’ 不行.

數據

相關文件

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

We explicitly saw the dimensional reason for the occurrence of the magnetic catalysis on the basis of the scaling argument. However, the precise form of gap depends

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

Talent shows give people a reason to practice and perfect their 24 , and the professional panel of judges gives them advice and criticism about how to become

About the evaluation of strategies, we mainly focus on the profitability aspects and use the daily transaction data of Taiwan's Weighted Index futures from 1999 to 2007 and the

*Teachers need not cover all the verbal and non-verbal cues in the list. They might like to trim the list to cover only the most commonly used expressions. Instead of exposing

Microphone and 600 ohm line conduits shall be mechanically and electrically connected to receptacle boxes and electrically grounded to the audio system ground point.. Lines in

Theory of Project Advancement(TOPA) is one of those theories that consider the above-mentioned decision making processes and is new and continued to develop. For this reason,