Kaohsiung J Med Sci June 2009 • Vol 25 • No 6 316

Schools are one of the most critical social contexts influencing adolescent health. They are in a unique position to provide a safety net, protecting adoles-cents (especially those in developing countries) from hazards that can affect not only their learning, but also their development and psychological wellbeing [1]. However, school failure during adolescence is a

powerful indicator of other high-risk behaviors, such as delinquency [2], substance abuse [3], and preg-nancy [4]. Adolescent school dropouts also reported poorer health than did their peers [3]. The psycholog-ical wellbeing of adolescents failing at school should be of major concern to educational and medical professionals.

A variety of demographic, personal, family, and school characteristics have been found to be associ-ated with adolescent school failure [5]. Meanwhile, several intervention programs have been designed to reduce the incidence of school suspensions or pre-vent school dropouts [4]. However, the experiences of adolescent students who have returned to school Received: Feb 11, 2009 Accepted: Apr 10, 2009

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr Cheng-Fang Yen, Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, 100 Tzyou 1stRoad, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan.

E-mail: chfaye@cc.kmu.edu.tw

A

DVERSE

S

ITUATIONS

E

NCOUNTERED BY

A

DOLESCENT

S

TUDENTS

W

HO

R

ETURN TO

S

CHOOL

F

OLLOWING

S

USPENSION

Cheng-Fang Yen1,2and Hui-Ting Wang3

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, 2Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University,

Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and 3Special Education, College of Education, University of Washington,

Seattle, United States.

This study aimed to investigate the adverse personal, family, peer and school situations encoun-tered by adolescent students who had returned to school after being suspended. This was a large-scale study involving a representative population of Taiwanese adolescents. A total of 8,494 adolescent students in Southern Taiwan were recruited in the study and completed the question-naires. The relationships between their experiences of suspension from school and adverse per-sonal, family, peer, and school situations were examined. The results indicated that 178 (2.1%) participants had been suspended from school at some time. Compared with students who had never been suspended, those who had experienced suspension were more likely to report depres-sion, low self-esteem, insomnia, alcohol consumption, illicit drug use, low family support, low family monitoring, high family conflict, habitual alcohol consumption, illicit drug use by family members, low rank and decreased satisfaction in their peer group, having peers with substance use and deviant behaviors, low connectedness to school, and poor academic achievement. These results indicate that adolescent students who have returned to school after suspension encounter numerous adverse situations. The psychological conditions and social contexts of these individu-als need to be understood in depth, and intervention programs should be developed to help them to adjust when they return to school and to prevent school dropouts in the future.

Key Words:adolescent, depression, insomnia, peer, suspension of schooling (Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009;25:316–24)

following suspensions have seldom been investigated. There are several reasons for studying the experi-ences of previously suspended adolescent students. First, being older than their classmates is an immedi-ate stressor that can increase their difficulties in inter-acting with their classmates, so further increasing the risk of dropping out in the future [6]. Second, the stu-dents might have been suspended from school for various reasons, such as mental health disturbances, learning difficulties, family predicaments, or behav-ioral problems [5]. These problems may persist after the students return to school, so continuing to ham-per their school life and learning. Third, suspension from school can have a negative impact on an adoles-cent’s self-esteem and parent-child relationship, which further increases stress [7]. Last, the adolescents might spend time with peers outside the campus before or during the period of suspension. They may thus learn from peers risky behaviors that negatively impact health [8], which will further increase their difficul-ties in adjusting after their return to school. It is there-fore important to examine the adverse personal, family, peer and school situations encountered by adolescent students after their return to school following suspen-sion. The results of such studies will provide useful information to help in the development of interven-tion strategies to improve psychosocial wellbeing and prevent further school dropout.

This large-scale, cross-sectional study aimed to examine the adverse personal, family, peer and school situations encountered by adolescent students after their return to school following suspension, based on a representative population of Taiwanese adoles-cents. We hypothesized that adolescent students with the experience of suspension from school were more likely to report a variety of adverse personal and social situations than their peers without the experi-ence of suspension.

P

ATIENTS ANDM

ETHODSSubjects

The current investigation was based on data from the Project for the Health of Adolescents in Southern Taiwan, which collected data from three metropolitan cities and four counties. In 2004, there were 257,873 ado-lescent students in 209 junior high schools and 202,456 adolescent students in 140 senior high/vocational

schools in this area. Based on the definitions of urban and rural districts in the Taiwan Demographic Fact Book [9] and school and grade characteristics, a strat-ified random sampling strategy was used with the final goal of ensuring proportional representation of districts, schools, and grades. Twelve junior high and 19 senior high/vocational schools were randomly selected from urban districts; similarly, 11 junior high and 10 senior high/vocational schools were randomly selected from rural districts. The classes of these schools were further stratified into three levels based on grade in both junior high and senior high/voca-tional schools. Finally, 207 classes containing a total of 12,210 adolescent students were randomly selected based on the ratio of students in each grade.

Research assistants explained the purpose and procedure of the study to the students in class, empha-sizing respect for their privacy, and encouraging them to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from the adolescents prior to participation, and the participants were then invited to complete the research questionnaires anonymously. The proto-col was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University. We also recruited 76 adolescents (40 junior high school students and 36 senior high school students) and their parents into a pilot study to examine the reliability and validity of the research instruments.

Instruments

The experience of suspension from school

To determine the adolescents’ previous experiences of suspension from school and to differentiate it from truancy, we asked: “Have you ever been temporarily suspended by the school?” The kappa coefficient for agreement between participants’ self-reported expe-rience of suspension and their parents’ reports was 0.882 (p< 0.001).

The Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale (CES-D)

We used the 20-item Mandarin-Chinese version [10] of the CES-D [11] to assess the frequency of depres-sive symptoms during the preceding week. This scale has previously been used to evaluate depression among Taiwanese adolescents [12]. Cronbach’s alpha for the CES-D in the present study was 0.93 and the 2-week test–retest reliability was 0.78. A previous study among non-referred adolescents in Taiwan found

that adolescents with major depressive disorder had a higher total CES-D score than those without major depressive disorder [12]. For the purpose of statisti-cal analyses, we classified the adolescent students whose total CES-D score was ≥ the 85thpercentile of

all participants as having significant depression.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

The RSES contains 10 4-point items that assess sub-jects’ current self-esteem with good reliability and construct validity [13]. The scale yields a single over-all score of self-esteem, with high scores indicating high levels of self-esteem. It has previously been used to evaluate the levels of self-esteem among Taiwanese adolescents, and low self-esteem was found to be related to adolescents’ deviant behaviors [14]. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.86 and the 2-week test–retest reliability was 0.70. In this study, we classified adolescents whose total RSES score was ≤ the median as having low self-esteem.

Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS-8)

We used the self-reported 8-item AIS-8 to assess the severity of insomnia during the preceding month [15]. The first five items of the AIS-8 assessed the difficul-ties with sleep induction, awakenings during the night, early morning awakening, total sleep time, and over-all quality of sleep. The last three items assessed the next day consequences of insomnia, including the prob-lems with sense of wellbeing, functioning, and sleepi-ness during the day. The items of the AIS-8 correspond to the criteria for the diagnosis of insomnia according to the 10thversion of the International Classification of

Diseases [16]. Each item of the AIS-8 can be rated from

0 to 3, with higher total scores indicating more severe insomnia. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.67 and the 2-week test-retest reliability was 0.72. The total AIS-8 score was significantly associated with total nocturnal sleep hours (Pearson’s correlation,

r=–0.256; p<0.001) and depression (r=0.498; p<0.001).

We defined the adolescents whose total AIS-8 score was > the 85th percentile of the population in this

study as those with significant insomnia.

Experience in Substance Use (Q-ESU)

Two items of the Q-ESU were used to inquire dichoto-mously whether participants had regularly drank alcohol every week and had ever used illicit drugs during the preceding year [17]. The 2-week test–retest

reliabilities for the two items in this study (kappa) were 0.723 (p< 0.001) for regular alcohol consump-tion and 0.656 (p< 0.001) for illicit drug use.

Family APGAR Index (APGAR)

The Chinese-version family APGAR [18], which meas-ures satisfaction with aspects of family support, is based on the original version developed by Smilkstein [19]. The 5-point response scales reflect frequency ranging from never to always. High scores indicate good family support. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.84 and the 2-week test–retest reliability was 0.72. We classified the students with a total APGAR score < the median of the participants in this study as receiving low family support.

Adolescent Family and Social Life Questionnaire (AFSLQ)

We adapted the subscale of the AFSLQ to assess the levels of family conflict (3 items), family monitoring (4 items), subjective ranking and satisfaction in their peer group (4 items), and connectedness to school dur-ing the previous month. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.62 to 0.74 and the 2-week test–retest reliability from 0.64 to 0.71 [17]. We classified the students whose scores for the four subscales were > the median of the partic-ipants as having high family conflict, low family mon-itoring, low rank and decreased satisfaction in their peer group, and low connectedness to school. The AFSLQ also assessed habitual alcohol consumption (alcohol consumption 3 times per week) and illicit drug use among the parents and siblings, as well as regu-lar alcohol consumption every week, illicit drug use, and deviant behaviors (using violence, joining a gang, or having any criminal record) among their peers.

We also collected information on participants’ sex, age, parents’ marriage status, parents’ educational lev-els, and the rank of academic performance. The partic-ipants whose academic performance during the recent semester ranked in the lowest one-third of their class were considered to have poor academic achievement.

Procedure

A total of 11,111 (91.0%) adolescent students returned their written, informed consents. The adolescents were asked to complete the questionnaire anonymously, based on the explanations of the research assistants and under their direction. All students received a gift worth NT$33 (US$1) at the end of the assessment.

Of these, 8,494 (76.4%) participants completed all re-search questionnaires without omission.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The relationships between the experience of suspension from school and sociode-mographic characteristics, including sex, age (<15 years old vs.≥ 15 years old), residential background (urban

vs. rural), parents’ marriage status (intact vs. separated/

divorced) and parents’ educational levels (≤ 9 years

vs.>9 years) were examined using logistic regression

analysis. The relationships between the experience of suspension from school and adverse personal (signif-icant depression, low self-esteem, signif(signif-icant insom-nia, regular alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use), family (low family support, low family monitoring,

high family conflict, and habitual alcohol consumption and illicit drug use among family members), peer (low rank and decreased satisfaction in the peer group, peers’ regular alcohol consumption, illicit drug use, and deviant behaviors), and school situations (low con-nectedness to school and poor academic achievement) were further examined using logistic regression analy-sis models after adjusting for the effects of sociodemo-graphic characteristics. A two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

R

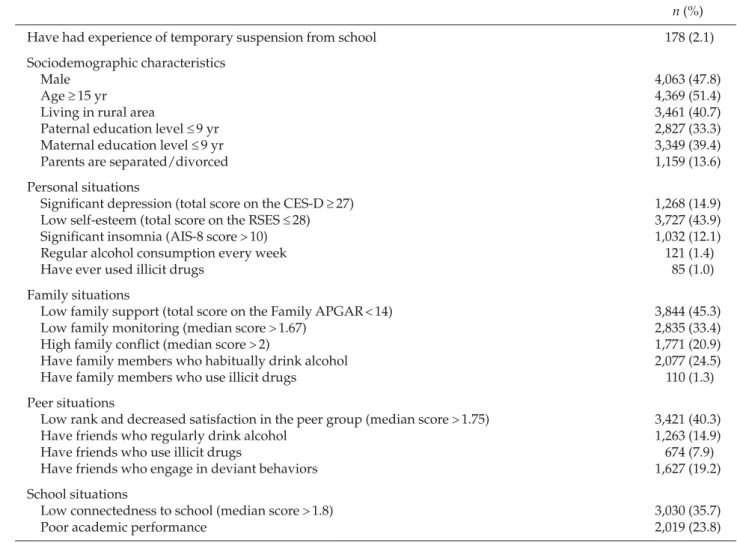

ESULTSThe sociodemographic characteristics and adverse personal, family, peer and school situations reported by the participants are shown in Table 1. Out of a total

Table 1.Suspension from school, sociodemographic characteristics, and adverse personal, family, peer and school situations among 8,494 adolescent students

n (%)

Have had experience of temporary suspension from school 178 (2.1)

Sociodemographic characteristics

Male 4,063 (47.8)

Age ≥ 15 yr 4,369 (51.4)

Living in rural area 3,461 (40.7)

Paternal education level ≤ 9 yr 2,827 (33.3)

Maternal education level ≤ 9 yr 3,349 (39.4)

Parents are separated/divorced 1,159 (13.6)

Personal situations

Significant depression (total score on the CES-D ≥ 27) 1,268 (14.9)

Low self-esteem (total score on the RSES ≤ 28) 3,727 (43.9)

Significant insomnia (AIS-8 score > 10) 1,032 (12.1)

Regular alcohol consumption every week 121 (1.4)

Have ever used illicit drugs 85 (1.0)

Family situations

Low family support (total score on the Family APGAR< 14) 3,844 (45.3)

Low family monitoring (median score > 1.67) 2,835 (33.4)

High family conflict (median score > 2) 1,771 (20.9)

Have family members who habitually drink alcohol 2,077 (24.5)

Have family members who use illicit drugs 110 (1.3)

Peer situations

Low rank and decreased satisfaction in the peer group (median score > 1.75) 3,421 (40.3)

Have friends who regularly drink alcohol 1,263 (14.9)

Have friends who use illicit drugs 674 (7.9)

Have friends who engage in deviant behaviors 1,627 (19.2)

School situations

Low connectedness to school (median score > 1.8) 3,030 (35.7)

Poor academic performance 2,019 (23.8)

CES-D = The Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale; RSES = Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; AIS-8 = the Athens Insomnia Scale.

Table 2.Relationships between suspension from school and sociodemographic characteristics

Wald OR 95% CI

Male 7.090* 1.506 1.114–2.035

Age≥ 15 yr 34.830† 2.777 1.978–3.899

Living in rural area 1.747 1.229 0.905–1.668

Paternal education level ≤ 9 yr 4.451‡ 1.449 1.027–2.044

Maternal education level ≤ 9 yr 0.165 1.073 0.763–1.511

Parents are separated/divorced 13.387† 1.937 1.359–2.761

*p< 0.01; †p< 0.001; ‡p< 0.05. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. of 8,494 adolescent students, 178 (2.1%) had been sus-pended from school.

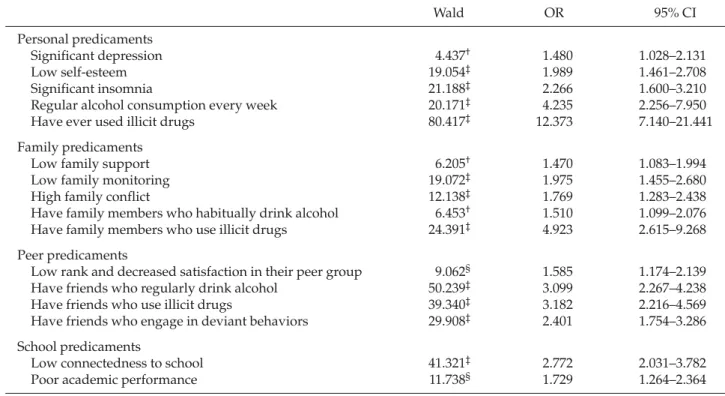

The relationships between the experience of suspen-sion and sociodemographic characteristics analyzed by logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 2. The results indicated that adolescent students who were male, older, and whose paternal education level was low and whose parents’ marriage was broken, were more likely to have been suspended. The effects of these significant sociodemographic characteristics were adjusted for when the relationships between the experience of suspension and adverse personal, family, peer, and school situations were examined using logis-tic regression analysis (Table 3). Adolescent students who had experienced suspension were more likely to

report significant depression, low self-esteem, signif-icant insomnia, regular alcohol consumption every week and use of illicit drugs than those who had not been suspended. Students who had been suspended were more likely to encounter multiple adverse family situations, including low family support, low family monitoring, high family conflict, and habitual alcohol consumption and illicit drug use among family mem-bers than students who had not been suspended. They were also more likely to report multiple adverse peer situations, including low rank and decreased satis-faction in their peer group and having peers who reg-ularly drank alcohol, used illicit drugs, and had deviant behaviors, and to report low connectedness to school and poor academic achievement.

Table 3.Relationships between suspension from school and adverse personal, family, peer and school situations analyzed using logistic regression analysis models*

Wald OR 95% CI

Personal predicaments

Significant depression 4.437† 1.480 1.028–2.131

Low self-esteem 19.054‡ 1.989 1.461–2.708

Significant insomnia 21.188‡ 2.266 1.600–3.210

Regular alcohol consumption every week 20.171‡ 4.235 2.256–7.950

Have ever used illicit drugs 80.417‡ 12.373 7.140–21.441

Family predicaments

Low family support 6.205† 1.470 1.083–1.994

Low family monitoring 19.072‡ 1.975 1.455–2.680

High family conflict 12.138‡ 1.769 1.283–2.438

Have family members who habitually drink alcohol 6.453† 1.510 1.099–2.076

Have family members who use illicit drugs 24.391‡ 4.923 2.615–9.268

Peer predicaments

Low rank and decreased satisfaction in their peer group 9.062§ 1.585 1.174–2.139

Have friends who regularly drink alcohol 50.239‡ 3.099 2.267–4.238

Have friends who use illicit drugs 39.340‡ 3.182 2.216–4.569

Have friends who engage in deviant behaviors 29.908‡ 2.401 1.754–3.286

School predicaments

Low connectedness to school 41.321‡ 2.772 2.031–3.782

Poor academic performance 11.738§ 1.729 1.264–2.364

D

ISCUSSIONIn this study, we found that adolescent students who had returned to school after being suspended encoun-tered numerous adverse personal, family, peer, and school situations. The results indicated that returning to school did not signify the end of their problems. On the contrary, students who had been suspended had to face a variety of situations that could inevitably influence their learning and adjustment when they returned to the campus. Although the cross-sectional design of this study limited our ability to demon-strate causal relationships between previous suspen-sion and current personal and social adverse situations, the results should remind educational and medical professionals of the importance of considering the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescent students with experience of suspension from school.

In this study, adolescent students who had been suspended from school were more likely than those who had not to report depression, insomnia, regular alcohol consumption and use of illicit drugs. Previous studies suggested that depressive disorders [20] and sleep disturbances [21] were strong predictors of school dropout. The symptoms of depression, such as psy-chomotor irritability or retardation and loss of interest, can be directly responsible for educational under-achievement [22]. Sleep disturbance can result in lapses of attention, indifference, and reduced motivation [23], which can also compromise academic achieve-ment. Conversely, school dropout is also a potential risk factor for mental disorders [24]. Habitual use of alcohol and illicit drugs, such as ecstasy, can damage individuals’ cognitive functioning [25], which may fur-ther result in learning difficulties. Although the occur-rences of adolescent depression, sleep disturbance, and substance use all need to be carefully monitored, they are not easily identified by teachers and peers and do not often interfere with general classroom rules. It is strongly incumbent on clinicians and teachers to ask about and identify these conditions in adolescents who are performing poorly in school [4].

In this study, adolescent students with experience of suspension had lower self-esteem than did their peers. Several previous studies have found that low self-esteem is a psychosocial indicator of school dif-ficulties [4,7]. Hay and colleagues [26] found that students with low self-esteem had fewer positive class-room characteristics in terms of classclass-room behavior,

cooperation, persistence, leadership, anxiety, expec-tations for future schooling, and peer interactions, compared with their peers with high self-esteem. Self-esteem is a powerful motivational force for ado-lescents and low self-esteem is correlated with depres-sion, suicidal ideation, delinquency, and adjustment problems [27], thus enhancing self-esteem should be an important outcome goal of intervention programs for students suspended from schools [28].

In this study, students who had been suspended were more likely than those who had not to report low family support, low family monitoring, high family conflict, and family members’ habitual alcohol con-sumption and illicit drug use. The family is a social unit that is important for development during adolescence. Low family support, low family monitoring, and high family conflict have been found to increase the risk of psychological disturbance and drug use in adoles-cents [29]. Meanwhile, substance use by family mem-bers is one of the family adversities that can increase the risk of developing psychopathologies among ado-lescents [30]. The results of this study indicated that interventions to improve adjustment and prevent school dropout in students with experience of suspen-sion should evaluate family conditions and encour-age the cooperation of family members.

Our results showed that students with experience of suspension were also more likely than those with-out to report low rank and decreased satisfaction in their peer group and to have peers who regularly drank alcohol, used illicit drugs, and had deviant behaviors. Peer groups can provide adolescents with emotional support and the chance to practice interac-tion skills [31]. Good peer relainterac-tionships have been proven to not only buffer adolescents against stress associated with adjustment [32], but also to mitigate the effects of negative cognition and alleviate depres-sion [33]. However, poor quality of peer interactions may cause distress [34], and affiliation with peers who engage in substance use [35] or who exhibit delinquent behaviors [29] can increase the risk of substance use in adolescents. Although it is possible that peer substance use may primarily reflect the ten-dency for adolescents to select similarly inclined companions [36], the results of this study suggest that it is necessary to monitor the peers that sus-pended students interact with, in order to prevent the occurrence or exacerbation of substance use and delinquent behaviors.

In this study, students who had been suspended from school were also more likely to report low con-nectedness to school and poor academic achievement, compared with their peers. The level of connected-ness to school is a result of interactions with individ-ual students, teachers, and the school environment [37]. The ethos of the school, rather than the school’s socioeconomic status, is a more reliable predictor of a school’s disposition to suspend students [38]. Students’ perceptions that teachers cared and were fair-minded were seen as critical issues with respect to connected-ness to schools [39]. A competent teacher must be aware of student diversity and be equipped with the required tools and appropriate environment to provide the necessary help for students who do not get positive reinforcement from academic achievements [40].

The strengths of this study lie in the fact that it is one of few studies examining the adverse personal, family, peer and school situations encountered by adolescent students after they return to school following suspen-sion. Furthermore, this study involved a large, repre-sentative population of adolescents. The selection bias was minimized by sampling participants from a non-referred, representative school-based sample. However, some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, although examining the antecedents of suspension was not the major aim of this study, its cross-sectional design limited our ability to identify causal relationships between suspension and per-sonal and social predicaments. Second, the data were provided by the adolescents themselves, and infor-mation was not collected from parents or teachers. Third, we did not ask the participants why and when they had previously been suspended from school.

Implications

In this study, adolescent students who had returned to school after being suspended were found to encounter a variety of personal, family, peer, and school predica-ments. Given that these multidimensional, adverse situations may increase the risk of future school dropout [9], we suggest that educational and medical professionals should make efforts to understand the personal psychological conditions and behaviors of students who have been suspended, as well as their social contexts and their attitudes towards school. Intervention programs should be developed to improve their ability to adjust when returning to school and to prevent future school dropout.

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTSThis study was supported by a grant (NSC 93-2413-H-037-005-SSS) from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

R

EFERENCES1. Kapur M. Mental Health in Indian Schools. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1997.

2. Weller NF, Tortolero SR, Kelder SH, et al. Health risk behaviors of Texas students attending dropout preven-tion/recovery schools in 1997. J Sch Health 1999; 69:22–8.

3. Aloise-Young PA, Cruickshank C, Chavez EL. Cigarette smoking and perceived health in school dropouts: a comparison of Mexican American and non-Hispanic white adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 2002;27:497–507. 4. Reiff MI. Adolescent school failure: failure to thrive in

adolescence. Pediatr Rev 1998;19:199–207.

5. Dryfoos JG. Adolescents at Risk: Prevalence and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

6. Beekhoven S, Dekkers H. Early school leaving in the lower vocational track: triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data. Adolescence 2005;40:197–213. 7. Hay I. Gender self-concept profiles of adolescents

sus-pended from high school. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:345–52.

8. Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Epstein EE.

Theories of etiology of alcohol and other drug use dis-orders. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, eds. Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook, 1stedition. New York: Oxford,

1999:50–72.

9. Ministry of the Interior. 2001 Taiwan-Fukien Demographic Fact Book, Republic of China. Taipei, Taiwan: Executive Yuan, 2002. [In Chinese]

10. Chien CP, Cheng TA. Depression in Taiwan: epidemio-logical survey utilizing CES-D. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1985;87:335–8.

11. Radloff LS. The CSE-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement 1977;1:385–401.

12. Yang HJ, Soong WT, Kuo PH, et al. Using the CES-D in a two-phase survey for depressive disorders among non-referred adolescents in Taipei: a stratum-specific likelihood ratio analysis. J Affect Disord 2004;82:419–30. 13. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. New

Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1965.

14. Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF. Gender differences in addiction to playing online games and related factors among Taiwanese adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005;193:273–7. 15. Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res 2000;48:555–60.

16. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO, 1992. 17. Yen CF, Yang YH, Ko CH, et al. Substance initiation

sequences among Taiwanese adolescents using metham-phetamine. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;59:683–9. 18. Chau TT, Hsiao TM, Huang CT, et al. A preliminary

study of family Apgar index in the Chinese. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1991;7:27–31.

19. Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract 1978;6:1231–9.

20. Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, et al. Social con-sequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1026–32.

21. Shin C, Kim J, Lee S, et al. Sleep habits, excessive day-time sleepiness and school performance in high school students. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;57:451–3. 22. Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health,

educa-tional and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:225–31. 23. Hughes RG, Rogers AE. First, do no harm. Are you

tired? Sleep deprivation compromises nurses’ health and jeopardizes patients. Am J Nurs 2004;104:36–8. 24. Swaim RC, Beauvais F, Chavez EL, et al. The effect of

school dropout rates on estimates of adolescent sub-stance use among three racial/ethnic groups. Am J Public Health 1997;87:51–5.

25. Baggott MJ. Preventing problems in Ecstasy users: reduce use to reduce harm. J Psychoactive Drugs 2002;34: 145–62.

26. Hay I, Ashman A, van Kraayenoord C. The educa-tional characteristics of students with high or low self-concept. Psychol Sch 1998;35:391–400.

27. Adams GR. Adolescent development. In: Gullotta TP, Adams GR, eds. Handbook of Adolescent Behavioral Problems: Evidence-based Approaches to Prevention and Treatment. New York: Springer, 2005:3–16.

28. Cox SM, Davidson WS, Bynum TS. A meta-analytic assessment of delinquency-related outcomes

of alternative education programs. Crime Delinq 1995; 41:219–34.

29. Guo J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, et al. A developmental analysis of sociodemographic, family, and peer effects on adolescent illicit drug initiation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:838–45.

30. Goebert D, Nahulu L, Hishinuma E, et al. Cumulative effect of family environment on psychiatric sympto-matology among multiethnic adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2000;27:34–42.

31. Gemelli R. Normal Child and Adolescent Development. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996. 32. Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal

competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Dev 1990;61:1101–11.

33. Liu YL. The role of perceived social support and dysfunctional attitudes in predicting Taiwanese ado-lescents’ depressive tendency. Adolescence 2002;37:823–34. 34. Kandel DB, Davies M. Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents: an empirical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:1205–12.

35. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The preva-lence and risk factors associated with abusive or haz-ardous alcohol consumption in 16-year-olds. Addiction 1995;90:935–46.

36. Bauman KE, Ennett ST. Peer influence on adolescent drug use. Am Psychol 1994;49:802–22.

37. Lee VE, Burkam DT. Dropping out of high school: the role of school organization and structure. Am Educ Res J 2003;40:353–93.

38. Walker HM. The Acting-out Child. Coping with Classroom Disruption, 2nd edition. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon,

1995.

39. Resnick MD, Bearman P, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997; 278:823–32.

40. Weinberg WA, Gallagher LS, Harper CR, et al. The impact of school on academic achievement. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 1997;6:593–606.

收文日期:98 年 2 月 11 日 接受刊載:98 年 4 月 10 日 通訊作者:顏正芳醫師 高雄醫學大學附設醫院精神科 高雄市 807 三民區自由一路 100 號