行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

國際聯合承攬之組織策略與績效關係之實證研究(I)

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2221-E-002-321- 執 行 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 96 年 10 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立臺灣大學土木工程學系暨研究所 計 畫 主 持 人 : 荷世平 共 同 主 持 人 : 朱文儀 計畫參與人員: 博士班研究生-兼任助理:葉崇熙 碩士班研究生-兼任助理:周展民 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 97 年 02 月 06 日

國際聯合承攬之組織策略與績效關係之實證研究 (I)

Abstract:

Among various joint ventures, International Construction Joint (Ventures ICJVs)have emerged as a popular approach worldwide to developing large scale projects through international participation. Evidence from literature shows that the design of an organization has critical impacts on the performance of the organization. However, there exists no particular organizational design or form that suits all organizations. In ICJVs, characteristics of each project or JV team determine which organizational form will yield better performance. A model, based on economic analysis and represented by several hypotheses obtained from the analysis, will be developed. Furthermore, we will empirically test the proposed model and hypotheses.

We define two basic and distinct organizational governance structures for ICJVs, namely Separately Managed JVs (SMJ) and Jointly Managed JVs (JMJ). JMJ is characterized by that all partners jointly share profits and risks of the ICJVs although distinct tasks may still be assigned to each firm, and that the JV management makes most decisions, which will be followed by all partners. On the contrary, SMJ is defined by the opposite extreme of the SMJ. The empirical results confirm our hypotheses as follows. Hypothesis One: An ICJV with larger cultural difference among partners is more likely to adopt SMJ as the organizational control structure, and vice versa. Hypothesis Two: An ICJV with greater trust among partners is more likely to adopt JMJ, and vice versa. Hypothesis Three: An ICJV where partners have higher needs for procurement autonomy is more likely to adopt SMJ, and vice versa. Hypothesis Four: An ICJV with stronger motivation in partners for learning is more likely to adopt JMJ, and vice versa.

Although there is a voluminous body of research in alliances, few empirical studies have examined the effects of a strategic fit between alliance forms. Our research could contribute to the understanding of alliance in ICJVs from the perspectives of theoretical hypotheses and empirical evidences. We may conclude that the choice of governance structures are determined by the characteristics of ICJVs, namely, the cultural difference, trust between partners, the need for firm’s procurement autonomy, the motivation for learning in ICJVs.

0. Self-evaluation of the Research Project

This research was successfully conducted. Based on this project, two journal papers have been submitted to J. of Construction Engineering and Management for review. Sections 2 and 3 form the major content of the first paper submitted. The second paper submitted is based on sections 4 through 6 in this paper. This project also supported a PhD student to complete her PhD dissertation and trained several Master students.

1. Introduction

When we freely consume resources, we have no idea how our environment has changed and why. When joint ventures are omnipresent in construction, we think that we have known enough about joint ventures. What we do not know is why we need joint ventures, why not just use pure contracts, why different JVs can be oppositely organized, how to make the choice, why, etc. This is why it was so astounding to the world when the 1991 Nobel laureate Ronald Coase (1937) first tried to explain, in his seminal paper “The Nature of the Firm,” why some transactions are processed in “market” through contracting and some others are processed in a “firm” by integrating transactional parties together under a roof. Organizational scholars have long recognized that governance structures and organizational control have critical impacts on the performance of an organization. Today, “institutions do matter” has become a taken proposition, rather than a subject of debating. In other words, strategic fit between an organizational structure and the business strategy or project situations plays an important role in determining performance (Yin and Zajac 2004; Horii 2004).

Strategic alliances, a popular organizational form for undertaking international projects, have been widely accepted by practitioners and scholars as crucial strategic weapons for competing within domestic or global competitive arenas. Work by Borys and Jemison (1989) has a comprehensive discussion on the theoretical development and rationales of the existence of strategic alliances. Strategic alliances are “voluntary interfirm cooperative agreements” (Parkhe 1993). Types of strategic alliances may include equity joint ventures, non-equity alliances such as licensing agreements, and distribution and supply agreements, etc (Inkpen and Currall 2004). As argued by Cheng

et al. (2004), strategic alliances in the construction industry can provide some direct benefits including reduced risk, improved quality, reduced cost, completion on time and reduce work at the project level. In construction, strategic alliances are considered one of the major entry modes for the internationalization of firms and play an important role in the strategic planning of international firms.

Research on construction alliances has focused on issues such as: (1) rationales and benefits behind international construction alliances (Badger and Mullign 1995; Sillars and Kangari 1997); (2) governance structures of construction alliances (Ngowi 2007, Chen 2005); (3) performance or organizational success in alliances or joint ventures (Mohamed 2003; Sillars and Kangari 2004). In construction, the number of international joint ventures (IJVs) is growing rapidly, especially in developing countries, where ICJVs serve to satisfy the needs for national development and at the same time to prevent the economy from being dominated by foreign investors (Mohamed 2003). Due to the recent trend of utilizing ICJVs, international construction firms are faced with challenging decisions concerning ICJVs at an increasing frequency. Among these decisions, the choice of governance structure has a profound impact on the JV performance, but receives few attentions. Chen (2005) studies the entry modes for international construction markets and develops a model for entry mode selection. Work by Ngowi (2007) investigates how trust plays a crucial role in governance structure decisions. Ngowi (2007) defines two governance structures in construction alliances: joint ventures and partnering. He maintains that, based on the transaction costs rationale, partner trustworthiness encourages the use of partnering while partners without sufficient mutual trust tend to adopt joint ventures. Ngowi’s conclusion is generally consistent with the theoretic and empirical work in organization literature. One of the most discussed alliance governance issues in literature is the choice between equity

alliances and non-equity alliances, similar to Ngowi’s “joint ventures” and “partnering” in the construction industry. The distinction between equity and non-equity alliances discussed in literature shows that the choice of organizational forms has a strong linkage to the processes of transaction, or more precisely, the governance of an institution. In general, equity alliances are a more hierarchical structure unified under one roof through shared or common ownership and interests, whereas the non-equity alliances are a less hierarchical structure, focusing more on market mechanism and trust. However, many scholars also argue that the differences in transactional processes and alliance control between equity and non-equity alliances are not necessarily distinctive. For example, Hagedoorn (2002) points out that equity alliances can also act as semi-independent units that perform standard company functions such as manufacturing, and this feature allows companies to apply alliances in a broader strategic setting. Geringer and Hebert (1989), who made a significant contribution in studying joint venture control, argue that “control was not a strict and automatic consequence of ownership.” The best example of this kind of control can be seen in ICJVs, where the control of an ICJV can be very different from that of another ICJV, as we shall explicate later. Therefore, our paper departs from the choice between joint ventures and partnering and solely focuses on the control of joint ventures, discussing the types and choices of organizational forms in joint ventures.

Taking account of the common practice in ICJVs and the concept of organization control, we identify and define two distinctive organizational forms in ICJVs: Separately Managed Joint ventures (SMJ) and Jointly Managed Joint ventures (JMJ). In SMJ, a project is divided into a few distinctive tasks and each partner is primarily responsible, technically and/or financially, for its assigned tasks and makes decisions directly without the formal consent from other partners. On the contrary, all partners in

JMJ jointly share profits and risks and the JV officers make most decisions, which will be followed by all partners. Closer coordination and more frequent communications are extended to all levels of a JV organization. This paper aims to develop a theoretic framework of ICJV’s organizational control strategy to better organizational performance.

Although organizational literature does not address the choice of organizational control structures in ICJVs directly, the rich theories in literature serve as the foundations for developing the governance model for ICJVs. First, based on transaction-cost economics (TCE), minimization of transaction costs is considered a key mechanism in determining organizational governance (Gulati and Singh 1998); however, costs are not the only factors that stand to influence such decisions. Firm competence or capabilities also play a critical role in alliance governance. According to resource-based view (RBV), as a resource owner, a firm’s ability to create, appropriate, and sustain value from the owned resources is partly dependent on the firm’s ability to access the complementary resources and how well the resources are protected and exploited. This is why Williamson (1999), one of the most influential scholars in developing TCE, calls for more research into investigating how existing firm capabilities influence governance. In this paper, we attempt to address how the RBV can complement the standard TCE approach to governance choice. With the dual theoretical lens, this study analyzes factors that influence firms’ control and the choice of organizational forms of ICJVs and develops an integrated model.

The organization of the remaining sections is as follows. Sections 2 and 3 present an integrated conceptual framework for the ICJVs’ choices of organizational control structure. Sections 4 through 6 are the empirical study using a rigorous case study methodology.

2. Organizational Control Structures of ICJVs

Governance Structures and Organizational Control

The term “governance structure” is frequently used and discussed in organization literature, but it often vaguely refers to only one or two dimensions of governance structures. In fact, governance structures can be conceptualized through different sets of decision making, coordination mechanisms, and incentives (Yin and Zajac 2004), and with different levels of influence in controlling and coordinating the activities in a partnership (Gulati 1998). However, most researchers focus on the incentives and ownership dimensions. For example, according to the transaction cost perspective, the two basic types of governance structures are “hierarchy” and “market.” The central difference of the two structures is that hierarchy internalizes transactions under one unified ownership that eliminates transaction costs caused by the misaligned incentives and opportunism. Meanwhile, alliance structures are frequently classified as “equity” and “non-equity,” which are often considered the variations of “hierarchy” and “market” structures in alliances. However, since most ICJVs are equity alliances, traditional focuses such as “hierarchy or market” or “equity or not” are not effective enough in characterizing the different organizational structures in ICJVs. Also, because the key to managing international joint ventures is the integration, exploitation, and protection of strategic resources, control becomes the underlying mechanism for managing such resources (Mjoen and Tallman 1997) and determines how partners can influence the decision-making process and the joint venture outcomes. Thus, in this study, we shall focus on the central dimension of governance structure, namely, control, which, in the joint venture context, refers to “the process by which partners’ firms influence a joint

venture entity to behave in a manner that achieves partner objectives and satisfactory performance” (Inkpen and Currall 2004).

Moreover, since joint ventures involve shared ownership, partner’s relative ownership or equity shares are often considered a proxy of the joint venture control. Yet, this intuitive proxy appears to be somewhat oversimplified given the complexity of joint ventures. A representative empirical work by Mjoen and Tallman (1997) rejects the traditional governance hypothesis that “relies strictly on ownership share to delineate the degree of control.” They maintain that ownership is but one of the control mechanisms among others such as right of veto or partner’s technical superiority, and that “selective control” over some critical activities or resources is often more effective and desirable than overall control. Therefore, in order to more accurately identify and define the governance structures of ICJVs, we shall emphasize more on the governance structure taxonomy that focus on control.

Organizational Control Structures of ICJVs: Jointly Managed JV (JMJ) and Separately Managed JV (SMJ)

Geringer and Hebert (1989) argue that there are three dimensions of control: the mechanisms of control, the extent of control, and the focus of control. The mechanisms of control are not limited to ownership and may include other options such as the JV board of directors, formal agreements, JV planning process, and reporting relationships, etc. The extent of control over an IJV refers to the decision-making process in terms of the degree of centralization. The focus of control emphasizes selective or specific control over critical resources or activities and such control is more realistic and effective than hoping to control the entire JVs.

Following Geringer and Hebert (1989) and Mjoen and Tallman’s (1997) contributions in joint venture control, we will focus on the governance structures of ICJVs and study their finer-grained organizational control structures. Based on Geringer and Hebert’s operationalization of control, the following perspectives will be adopted to characterize and differentiate the organizational control structures of ICJVs: (1) the technical and financial responsibilities and claims associated with each partner, (2) the extent to which major decision making is decentralized to partnering firms, and (3) the levels and needs for coordination. The first perspective of ICJV control structures is related to the mechanisms and focus dimensions of control, concerning the division of responsible tasks, partners’ rights to control, and partners’ responsibilities. The second perspective is related to the mechanism and extent dimensions of control, concerning the assignment and duties of board of director, JV reporting relationship, and the degree of centralization. The third perspective is mainly associated with the focus of control, concerning the level of specific or overall control.

Based on the emphases mentioned above, here we identify and define two distinctive organizational control structures for ICJVs: Jointly Managed Joint ventures (JMJ) and Separately Managed Joint ventures (SMJ). Although the terms “Integrated JVs” and “Non-integrated JVs” are found in construction practice and literature to describe two different modes of governance structures (Chen 2005), we prefer not to use these somewhat “strong” terms because project owners may consider “non-integrated” an inferior structure due to the term’s semantic implication. In this paper, we shall use the terms JMJ and SMJ as they are semantically more neutral and they give more distinctive characteristics in the governance of construction joint ventures.

JMJ is characterized by (1) all partners jointly sharing profits and risks of a JV according to an agreed proportion even though distinctive tasks may still be assigned to

each firm; (2) JV management team making major decisions, which will be followed by all partners; (3) the needs for coordination and communication being extended to all levels of a JV organization. On the other hand, SMJ is characterized by (1) each firm being technically and financially responsible for its assigned tasks, which are often negotiated; (2) each firm making most decisions related to the assigned tasks without the needs of consent from other JV partners; (3) the needs for coordination and communication being limited to higher level managers and are minimum for individuals. We do not consider that the governance structure of an ICJV will be on the extreme side of either JMJ or a SMJ. The actual governance structures of ICJVs should be characterized by a spectrum between the two extremes. Therefore, when JMJ is proposed to be a preferred control structure in this paper, we mean that the structure on the spectrum closer to JMJ side is preferred.

In contrast, JMJ may seem to be more hierarchical than SMJ. Nevertheless, JMJ should not be considered equivalent to the “hierarchy” structure used in organization literature, particularly in the TCE literature. The major reason is that the typical “hierarchy” structure focuses mainly on the unified ownership as discussed above and, for this reason, is weak in differentiating the control of joint ventures (Mjoen and Tallman 1997). Since equity joint venture is typically considered a hierarchy structure in organization literature, the concern of choices between JMJ and SMJ in international equity joint venture should be more precisely regarded as the control structure choices under the hierarchy type of alliances. We submit that the differentiation of these two control structures, namely, JMJ and SMJ, are significant in the ICJV governance.

3. A Theoretical Model for the Choice of Organizational Control

Structure in ICJVs

An integrated model for the choice of governance structure in ICJVs is derived in this section. We will present a generic form of the integrated model and provide rationales for integrating the economic and strategic approaches into the model. The framework is expressed as a set of propositions, involving four determinants of control structures.

An Integrated Framework of Economic and Strategic Approaches

Academic interest in strategic alliance can be dated back to economic literature in the late 1970s. Afterwards, a number of managerial studies (Gulati and Singh 1998; Pisano et al. 1988; Pisano 1989; Gulati 1995; GarciaCanal 1996; Oxley 1997, 1999), mainly inspired by transaction cost economics (TCE) (Williamson 1975, 1985), have analyzed the alliance governance choices and their performance outcomes. TCE frames governance as a cost-minimizing and discriminating alignment between transaction costs and control (Williamson 1985). Despite TCE’s intuitive appeal, one major weakness of the TCE construct in the alliance domain is that it overemphasizes individual parties’ minimization of transaction costs, while holding other factors, such as value creation capabilities, constant. This weakness limits the TCE’s explanatory capability, particularly when dealing with hybrid structures such as joint ventures. A better perspective is desired for studying the governance decisions of ICJVs.

As the resource-based view (RBV) is widely used to explain the sources of competitive advantage of firms, the complementarity of resources owned by the firm

and its partners becomes one of the rare, valuable, immobile and non-substitutable resources, leading to a long-lived competitive advantage. For example, firms in an ICJV often seek partners with particular resources worth learning (e.g., technical capabilities or knowledge regarding local market) in pursuit of competitive advantage. Mowery et al. (1998) also highlight the importance of knowledge complementarities and partner-specific absorptive capacity in the partner choice decision. Furthermore, the competence perspective of RBV contends that alliances often aim at expanding partnering firms’ distinctive capabilities through interorganizational learning. In order to effectively support such competence enhancing processes, alliance partners rely on more sophisticated and integrated coordination mechanisms, rather than simple ownership pooling.

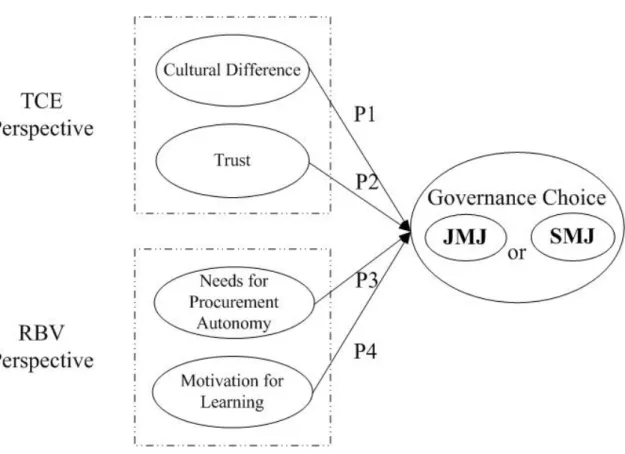

The discussion above highlights the complementary nature between RBV and TCE regarding the governance structures of alliances. This paper thus argues that an integrated framework fusing traditional TCE and recent RBV together could provide a more comprehensive explanation of the governance structure choices of ICJVs. The integrated model proposed in this paper is illustrated in Fig.1, depicting our corresponding four propositions. In the following sections, we shall derive and discuss each of the propositions.

[Insert Figure 1 here]

TCE Perspective: Contract-based Determinants of Governance Choice

Under TCE, governance forms that minimize the costs of exchange arising from uncertainty and asset specificity are considered efficient (Williamson 1985). Although scholars who hold traditional views like Williamson (1985) may see opportunism by

alliance partners as a key source of transaction costs, we take a broader view as emphasized by Matthews (1986) that transaction costs are “the overheads of conducting a set of transactions…and maintaining the system of property rights.” In this subsection, two major factors will be discussed and linked with the governance choices in ICJVs.

z Cultural Difference

Organizational culture refers to the set of values, beliefs, understandings, and ways of thinking that are common to the members of an organization (Daft 2001). Many problems experienced by firms in international joint ventures can be traced back to cultural difference (Meschi 1997; Horii et al. 2004). More specifically, partnering firms with bigger cultural distance will have greater differences in their organizational and administrative practices, employee expectations, and interpretation of and response to strategic issues (Park and Ungson 1997). In their modeling of cultural differences of IJVs, Horii et al. (2004) emphasize specifically the practices and values dimensions and study how different governance structures under various project situations react to cultural differences. Cultural differences play an important part in making the choice of governance structure and they often will increase the transaction costs, including information transmission cost, contracting cost, and monitoring and coordination costs. The impacts of cultural difference are especially emphasized in ICJVs because, first, cultural difference usually will be more significant in international JVs, and second, problems resulted from cultural difference are more difficult to resolve in ICJVs, whose lives are often not long enough, compared to regular organizations, for resolving cultural issues due to short project durations.

of “hierarchy,” and they conclude that “equity” joint ventures are preferable to “non-equity” alliances given greater cultural distance. Nevertheless, such conclusion does not necessarily lead to the use of JMJ. To begin with, the choice of JMJ or SMJ concerns the control of equity joint ventures, not the hierarchy or market choice. More specifically, the decision of JMJ or SMJ is made by holding the ownership structure of a joint venture fixed. Second, the rationale behind the belief that hierarchy can reduce transaction cost is due to the co-alignment of incentives through unified ownership (Sengupta and Perry 1997), rather than hierarchical management. Therefore, a more precise statement of a typical TCE view on alliances is that high transaction costs will call for the use of alliances that are characterized by higher co-ownership. As for the choice of JMJ or SMJ, we shall examine the transaction costs under different control structures.

In the following discussion, we share the broader view held by Matthews (1986) that transaction costs are the overheads of conducting a set of transactions. The question is: under different levels of cultural distance, what control structure minimizes transaction costs? Buckley and Casson (1996) maintains that “cultural homogeneity, acting through shared beliefs, reduces transactions costs by avoiding misunderstand…” In contrast, if the cultural difference is large, it should be comparatively costly to jointly manage a JV because there will be a lack of shared beliefs and values. Since the JMJ structure involves much higher degrees of coordination and communication, larger cultural difference will naturally increase the difficulty of collaboration and potential conflicts significantly. Therefore, following this logic, the SMJ, characterized by divided responsibility and minimal coordination and communication, can reduce the conflicts and costs of coordination that arise from organizational cultural differences. This phenomenon is commonly observed in the control of international subsidiaries or

colonies, where the key management personnels or politicians are often from local country to reduce the potential conflicts and the cost of management. Accordingly, we argue that when the cultural difference is larger, SMJ would be a more efficient form that reduces transaction costs, and vice versa.

Proposition 1: An ICJV with larger cultural difference among partners is more likely to

adopt SMJ as the organizational control structure, while an ICJV with smaller cultural differences is more likely to adopt JMJ.

z Trust

A distinctive characteristic of joint ventures is that partners have to deal not only with the uncertainty in the environment but also with the uncertainty arising from each other’s behavior (Harrigan 1985). Although TCE focuses on how transaction costs resulted from opportunism are minimized and does not regard trust a common or realistic factor that governs transactions, organization scholars (Dyer and Chu 2003; Mohr and Spekman 1994; Zaheer et al. 1998) have recently considered trust as a key relational factor or mechanism contributing towards alliance success. Ngowi (2007) shows that it is possible to establish trust among partners despite existing incentives for opportunism. Once trust is established, opportunistic behaviors by partners are not a significant issue to be concerned. The bottom line is that, holding other factors constant, trust can significantly reduce transaction costs caused by uncertainty and opportunism.

Trust is built upon an expectation that one partner has for another in the partnership such that their interaction is predictable and the behavior and responses are mutually acceptable to one another (Harrigan 1985). Trust among firms indicates the positive

belief that a partner will not take advantage of other partners (Powell 1990). Therefore, trust can also be considered as reliability, an important expectation of the partner in the alliance.

Based on the broader view of transaction costs (Matthews 1986), higher trust will reduce many transaction costs such as monitoring, outcome verification, and communication, etc. Therefore, when the level of trust is low, it should be comparatively expensive to jointly manage a joint venture and the partners will search for the best possible way to divide their tasks and corresponding responsibilities; that is, SMJ will be a better control structure in this case. Note that this conclusion does not contradict to the classic TCE based proposition or Ngowi’s proposition that “hierarchy” structure is a better choice when trust level is low, because, as we’ve shown in section 2, SMJ is not defined in terms of ownership structure and, thus, is not equivalent to the “market” structure in TCE literature. Taking the control perspective of governance, we submit that if the contracting firm has a higher level of trust toward other partners, JMJ, characterized by closer collaborations and more risk sharing, will be a more economic form for ICJVs in achieving their JV objectives.

A distinctive characteristic in the construction industry that reinforces the importance of trust is that, compared to the JVs in other industries, the reputation of each JV partner is tied up with the success or failure of the JV and the reputation impact is dependent on the control structure. When JMJ is adopted, the reputation impact will be more on all JV partners rather than on individual partners, yet when SMJ is adopted, it is easier for clients to identify who is responsible for the failure of the JV. In conclusion, if there is insufficient trust among partners, SMJ may be a better choice as it reduces the reputation related transactions costs and encourages each individual to take its responsibility.

Proposition 2: An ICJV with greater trust among partners is more likely to adopt JMJ,

while partners with less trust among them will tend to adopt SMJ.

RBV Perspective: Competence-based Determinants of Governance Choice

Although TCE plays a powerful part in determining the governance structure in terms of ownership structures such as the equity or non-equity alliances, it is less successful in differentiating the levels of control in various organizational forms (Mjoen and Tallman 1997). The key to the management of international joint venture is how to manage the strategic resources through proper control mechanism (Mjoen and Tallman 1997). From the competence-based perspective, different firms should take into accounts the characteristics of their specific resources and advantages to pursue different strategies for profits. Such view emphasizes value creation and sustainability of competitive advantages of a firm through continuous accumulating and utilizing valuable resources, including tangible and intangible resources (Das and Teng 2000; Wernerfelt 1984). For the purpose of effective management of resources, two other major determinants of the governance choice in international JVs are identified here: needs for procurement autonomy and motivation for learning. These two determinants are closely associated with selective and specific control in joint ventures as we shall explain in the followings.

z Needs for Procurement Autonomy

The procurement of construction inputs such as equipments, materials, and subcontractors is a critical process and activity in a large-scale construction project.

The major procured items may include materials, subcontractors’ work, and equipments. Particularly in construction industry, the success of a contracting firm lies in its capability to acquire inputs at the best price, quality, and reliability (Warszawski 1996). Thus, the procurement strategy or capability could become a major source of the competitive advantage of a construction firm. From the resource-based view (RBV), the procurement advantage may represent an intangible resource of a construction firm. The accumulation and utilization of such intangible resource can influence the long-term competitive advantages of the firm. When the exploitation of procurement advantage is considered crucial to a partner’s profitability, the partner would tend to require more flexibility or fewer restrictions imposed by other partners toward the procurement for the project. They may center on higher flexibility in choosing their own subcontractors or suppliers, and demand more independence between partners. This can be understood from the “focus” dimension of control argued previously. That is, when profits from procurement advantage are strategically important to a partnering firm, it is desirable to balance the control through various procurement arrangements, where each partner has focused control over specific procurement scope. For example, procurements can be decentralized and divided according to dollar amount, assigned tasks, or each partner’s comparative purchase advantage; alternatively, procurement can also be jointly made with higher priority given to each partner’s preferred suppliers.

In SMJ, each firm makes most decisions related to the assigned tasks without the needs of consent from other JV partners. Each partner is financially responsible for specific tasks, including procurement. Under these circumstances, contracting firms that emphasize more on procurement autonomy would prefer to adopt SMJ as the control structure. The third hypothesis for the choice of governance structure in ICJVs is proposed as follows.

Proposition 3: An ICJV where partners have higher needs for procurement autonomy is

more likely to adopt SMJ, while an ICJV with fewer needs from partners for procurement autonomy is more likely to adopt JMJ.

z Motivation for Learning

Organizational learning and learning from partners represent a primary motivation for firms to enter into alliance (Peng 2001). A firm’s organizational learning capability can create competitive advantages (Ulrich and Lake 1991; Inkpen and Crossan 1995). Khanna el al. (1998) emphasize that by picking up skills from its partners a firm can actually unilaterally earn private benefits. Thus, learning process can be considered the center to the evolution of a JV (Doz 1996) and become one major objective of a JV.

A firm’s motivation for learning refers to its tendency to view collaboration as an opportunity to learn (Hamel 1991). Learning from competitors or cooperating partners can be crucial to the creation and sustainability of a firm’s competitive advantage, since learning helps to achieve the objective of internalizing the desired external intangible resources such as know-how and expertise. From resource-based view (RBV), the motivation for learning is considered a major determinant of organizational control choices because the learning is a process of internalizing the complementary resources in construction JVs. A JV firm that has a strong motivation for learning will try to exert particular controls or influence over the organization that may facilitate the internalization of its partner’s know-how for private gains. In this case, JMJ may provide a better environment for learning because it provides a unified chain of command, requires more cooperation between individuals from different partners, and integrates operating procedures. In particular, since “learning by doing” is a major

approach to obtaining new knowledge and skills in the construction industry, learning is often naturally achieved under joint operation and management even though the partner with advanced knowledge may not intend to transfer the knowledge. This is also why the motivation for learning does not have to be “mutual,” because the learning can often be achieved without mutual consent. On the other hand, due to the characteristics of contracting firms’ resources, some firms in ICJVs may not have the needs to internalize other partners’ knowledge. For instance, firms may participate in ICJVs primarily for entering a new or unfamiliar market, instead of internalizing particular technology or complementary resources. Therefore, from the organizational control perspective, when learning is not an objective of an ICJV or the needs to internalize complementary resources are low, the control through advanced technology or capability will be emphasized and partners may prefer SMJ as the control structure. When learning is an objective of an ICJV, the needs to protect certain resources are lower and the objective to internalize complementary resources is easier to be achieved through jointly managing the joint venture. The last proposition is given as follows.

Proposition 4: An ICJV with stronger motivation in partners for learning is more likely

to adopt JMJ, while an ICJV where partners are less motivated in learning is more likely to adopt SMJ.

4. Case Study Design

Case Studies as an Empirical Inquiry and a Research Methodology

study is not an illustration or an application example of a theory. Case study is not a study of collections of historical events of a case. According to Yin (2003) and Flyvbjerg (2006), case studies are suitable for both generating and testing hypotheses. When a case study is used for empirical purpose, it can be called an “explanatory case study” (Yin 2003). For example, in their classic work “Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Allison and Zelikow (1999) used a single-case study to test and evaluate three competing theories in decision-making process. In his highly cited study of management information system (MIS) implementation, Markus (1983) successfully applied a single-case study to evaluate the theories concerning the resistance of system implementation. In this paper, we aim to evaluate the proposed propositions empirically. The logic of “evaluating” or “testing” a theory through case study is analogous to that of verifying a theory through experiments in physics or engineering and is fundamentally different from sampling logic in statistical methods. In analogy to an experiment, case studies can help us scientifically evaluate a theory by examining whether the outcomes of a case support that theory or rebut the rival theory. In other words, if the results of experiments or case studies fundamentally or substantially deviate from the theory or theory predictions, the theory should be questioned or revised. On the other hand, if the case evidences are consistent with the proposed propositions, the chance is higher that the proposed model is sound.

Case Selection and Data Collection

• Case selection

The case being studied is the Taiwan High Speed Rail (THSR) project, a $15 billion mega project that involves 8 major ICJVs in 12 construction contracts. This project was

selected because: 1) the project had 8 ICJVs to be analyzed, 2) the 8 JVs were in the same project environment, presumably providing a better controlled environment, 3) both types of ICJV governance structures were presented, and 4) the problem of data accessibility is not an issue in this project. Regarding data accessibility, we would like to stress that since the nature of the hypothesized determinants and our concerns toward ICJVs are considered very sensitive by most construction firms, finding top managers as our respondents and obtaining trust from respondents are both difficult and critical to the success of study. Fortunately, in the THSR project, we find channels to help us connect with the right people and earn trust from them in order to conduct in-depth interviews and data collection. Although multiple-case studies in general provide more compelling evidence than a single-case study, we decided to conduct this single-case study because it encompassed 8 units of analysis, each of which could be regarded a typical case of an ICJV.

• Data collection and reliability

Since there were limited public data related to the hypothesized determinants, we had to heavily rely on the data that were obtained during interviews, including the event descriptions and the potentially subjective opinions/judgments from the respondents. We verified the data from interviews by cross-referencing them to ensure the reliability of data. For example, comments or answers from one party were often compared with that from different parties, including a third party, e.g., the project owner. We conducted interviews with twelve top managers associated with the JV partnering firms and three top managers from the client, the THSR Inc., following a preplanned interview protocol. The protocol is designed to obtain 1) relevant background or numeric information, 2) the assessments of the hypothesized determinants and the organizational control

structures of an ICJV, and 3) the explanations for the concerned events. On average, each interview session with a respondent would last one and half hour. Most of the interview sessions were conducted during the twelve months between March 2005 and February 2006. A second round of interview was conducted in early 2007 so as to clarify some unclear information collected in the previous round and to resolve some confusion during the analysis.

5. Case Background and Assessments of Hypothesized Determinants

in Each ICJV

Background of the ICJVs in THSR

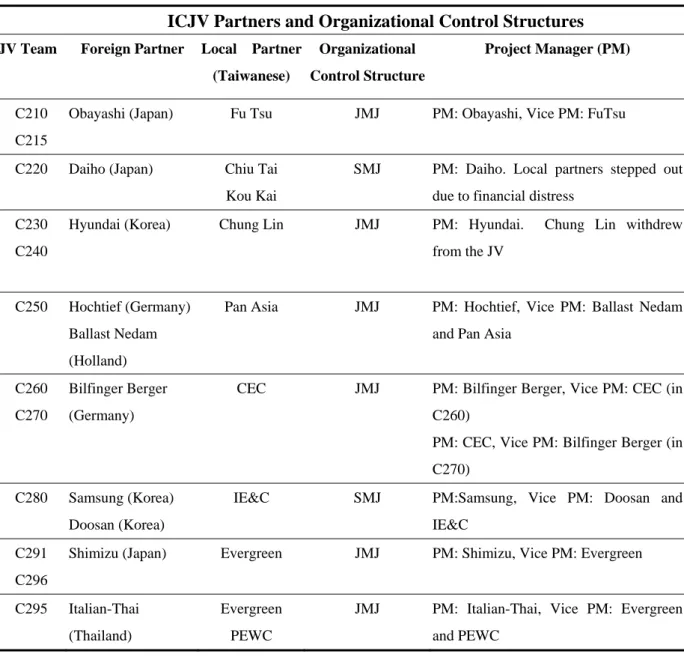

The THSR project is the largest transportation infrastructure in Taiwan. The actual costs of the project upon completion are about $15 billions, including $2 billions cost overrun. This project is developed through the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) scheme, a variation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), and is considered one of the largest projects in the world delivered through BOT. In the THSR project, there are 8 major ICJVs responsible for the 12 contracts of civil engineering works, not including rail construction and station construction. The budgeted costs for the 12 contracts are around $5.3 billion. The major international construction firms in the project include 2 firms from Germany, 1 from Holland, 3 from Japan, 3 from Korea, and 1 from Thailand. Table 1 shows the contract identification name, the JV team behind each contract, the partnering companies in each JV, the organizational control structure of each JV, and each JV’s official project managers. Among the 8 JVs, 6 adopt JMJ and 2 adopt SMJ.

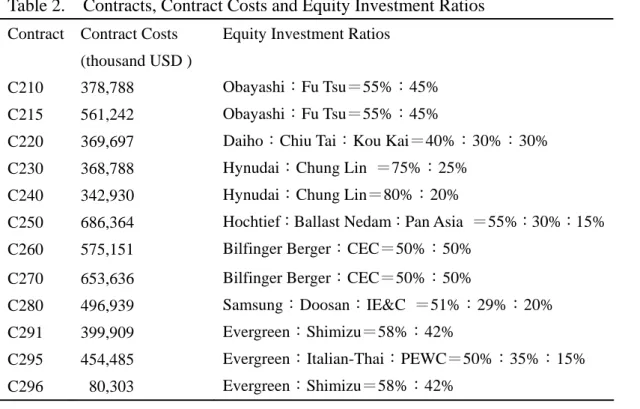

Although officially there were more than 8 JVs, we combined some of them. Table 1 shows the major 8 JVs after excluding those partnering firms that either withdrew from a JV at very early stage or had insignificant equity shares. Table 2 shows the budgeted costs of each contract, the equity ratios invested by each JV partner, and each partner’s number of members in the JV board.

[Insert Tables 1 and 2 here]

Among all JVs, the two JVs that adopted SMJ were the JV in C220 and that in C280. The three partners in C220 JV were: Daiho, responsible for the tunnel engineering, Chiu Tai, responsible for the foundation, and Kou Kai, responsible for the bridge engineering. However, during the construction, Chiu Tai and Kou Kai withdrew because of their financial distresses. As for the C280 JV, each of the three JV partners was technically and financially responsible for a specified length of civil works. Other than C220 and C280, it is worth noting that in C230/C240 JV, a jointly managed JV, the local partner Chung Lin withdrew from the JV after partnering for over one year. We shall explain later from the perspective of proposed model what may contribute to the dissolution of C230/C240 JV.

Analysis of the Determinants in Each JV

Here we shall explain and summarize our analysis of the governance structure determinant in each ICJV. In Section 4, we shall examine whether the decision for governance structure is consistent with proposed propositions. The assessment of the levels of each decisional variable is based on the descriptions, explanations, comments, and sometimes direct evaluations of the determinants from the respondents. In the following analysis, readers may consider to read thoroughly the explanation of

determinant assessment and briefly go through the summarizing tables, which will become very useful later in Section 4 during detailed analysis. Although we have tried to compare each JV’s characteristics summarized in each table cell as symmetric as possible, the contents in each cell may not be perfectly comparable because of the open interview process, data availability, and the applicability of the question to a specific JV.

Assessment of “Cultural Difference” in each JV

Table 3 summarizes the analysis of the cultural difference among partners in each JV. The major criteria for assessing the level of cultural difference in a JV are 1) the difference of corporate values reflected in partners’ focuses, 2) communication problems, and 3) interviewees’ comments. As shown in Table 3, the mismatch of the degrees of collectivism or individualism and partners’ difference in engineering background could be the main sources of cultural difference. However, we found that language difference didn’t cause substantial communication problems or the sense of cultural difference. Although we have clearly asked respondents not to confuse their ex-post experiences with ex-ante evaluation, it is still not easy to obtain the respondents’ accurate ex-ante evaluation of corporate value difference and the foresight on communication problems. Despite possible biases, the ex-post evaluation of cultural difference seemed to be useful and was not totally unrelated to ex-ante cultural difference.

According to Table 3, the levels of cultural difference in all JVs that adopt JMJ are low to moderate. Also, all interviewees considered that cultural difference is an important determinant of governance structure choices.

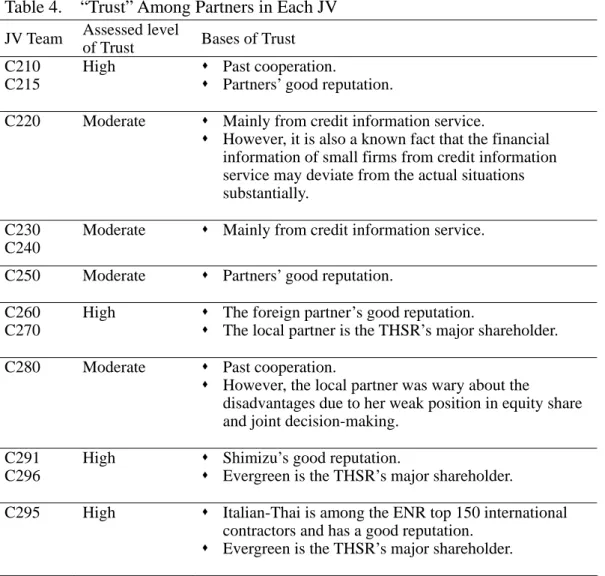

Assessment of “Trust” in each JV

Table 4 summarizes the analysis of trust among partners in each JV. The level of trust is assessed by each JV’s bases for the trust and the interviewees’ comments. Here “trust” is regarded as the “ex-ante” belief toward other partners. We find that many firms exhibited much lower ex-post trust after the “honeymoon” period of cooperation. Many factors, such as miscommunication, unrealistic expectation, poor management, or even cultural difference, could contribute to the disappointment toward others and the loss of trust. Since the interviewees’ evaluations of the trust might be confused with their ex-post experiences, we repeatedly reminded the respondents to evaluate the ex-ante trust level. In the study, we use the “bases of trust” to serve as a more objective criterion to corroborate with the respondents’ evaluation.

Table 4 shows the levels of trust in all JVs are at least moderate, indicating that trust may be a very basic requirement in forming a JV. Furthermore, good reputation and upbeat experiences of past cooperation are the most crucial ingredients for a high level of mutual trust. On the other hand, none of the JVs that adopt SMJ have a high level of mutual trust. Nevertheless, all interviewees agreed that trust is an important determinant of governance structure choices.

[Insert Table 4 here]

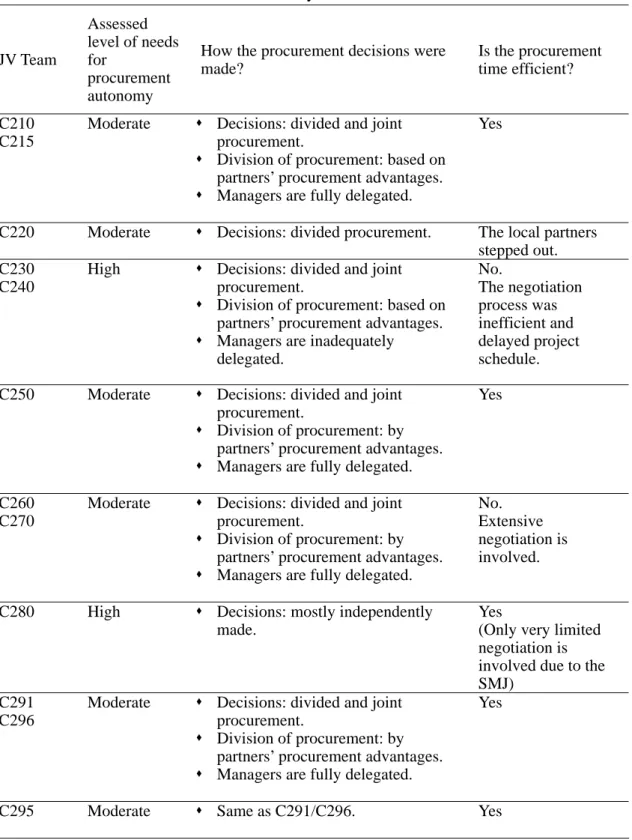

Assessment of “Needs for Procurement Autonomy” in each JV

The data obtained from the interview regarding this determinant were not satisfactory, mainly because respondents considered the procurement strategy a sensitive issue, more

difficult to be freely discussed. Table 5 summarizes the analysis of partners’ needs for procurement autonomy in each JV. The main criteria used to assess the level of needs include proportions of divided and joint procurements, interviewees’ responses, and negotiation efforts and efficiency in joint procurement. According to our findings, procurement is generally considered a key factor in reducing construction cost and increasing project profitability. At the same time, the needs for procurement autonomy vary from partner to partner because of some firm specific or project specific factors which are often entangled with project environments.

[Insert Table 5 here]

As shown in Table 5, the procurement in most JVs with JMJ is divided into three parts, where foreign or technically superior partners are often assigned to the procurement of special equipments or parts, local partners are assigned to the procurement of local materials or subcontractors, and the rest of the items are procured jointly. Based on the interview results, the division of procurement is desired because each partner may not only benefits from the autonomy of procuring assigned items, but also from utilizing partners’ different comparative specialties and purchasing advantages. For this reason, we consider the division of procurement an indication of needs for procurement autonomy and an arrangement of more “independent” decision-making. This also explains why all the assessed levels for procurement autonomy needs are at least in moderate level.

Another major criterion in our assessment is whether the negotiation efforts in joint procurement are high. We consider the negotiation efforts an indication of the extent to which each partner demands the procurement decisions to meet their specific requests. For example, the assessed level of needs for procurement autonomy is considered high in C230/C240 since their time on negotiation is extensively long and the process is

inefficient. Not surprisingly, all interviewees agree that the needs for procurement autonomy are an important determinant of governance structure choices.

Assessment of “Motivation for Learning” in each JV

Table 6 summarizes the analysis of motivation for learning in each JV. The major criteria for assessing the level of learning motivation are 1) whether learning is considered an objective of joining the JV, and 2) what to be learned. As shown in Table 6, most JVs adopting JMJ considered learning an objective of joining the JV: while foreign partners focus more on the learning of culture, business practice, suppliers and subcontractors in Taiwan, local partners emphasize more on learning specific technologies/skills or project management. All interviewees, except for those of C250 and C280, agreed that the motivation for learning is an important determinant of governance structure choices.

[Insert Table 6 here]

6. Case

Analysis:

Evidence and Model Evaluation

The purpose of this section is to explicate the assessment of the determinants in five selected JVs and to evaluate how the case evidences support the proposed model. Note that, in this section, since we will use the results previously tabulated in Section 3, readers are suggested to cross reference this section with Tables 1 through 6 for clarity.

As shown in Table 1 and 2, Obayashi is the foreign and leading partner and Fu Tsu is the local partner. Their equity share percentages are 55% and 45%, respectively. This JV adopts JMJ.

• Low assessed level of cultural difference

In terms of managerial decisions, both partners emphasized on prompt problem solving and thus the representing managers had full authorizations from parent companies. The only minor problem was the complaint of fairness issues. Because the employees are rewarded according to the evaluation and incentive systems of individual partners, which vary a lot, some complained that “it was not fair to be treated or rewarded differently under the same JV.” In terms of corporate value, both partners believed in quality and safety, especially for tunneling projects. Lastly, according to one respondent, “language difference did not create any major communication problems.”

• High assessed level of trust

The high level of trust between Obayashi and Fu Tsu is based on their upbeat experiences of past cooperation and the good reputation of each individual firm. For one thing, since Obayashi was the top construction firm in the world, Fu Tsu believed that Obayashi was well qualified in construction techniques, project management, and financial transparency. Obayashi also believed that “Fu Tsu was one of the reputable construction firms in Taiwan and that Fu Tsu would never do anything to damage the established reputation.” For another, Obayashi had a very positive impression on its major cooperation around ten years ago with Fu Tsu in the Taipei Metropolitan Rapid Transit project. The respondents had stated, “Without such trust, they could never work so closely under JMJ.”

Both partners considered that they had good relationships with their suppliers and each partner had different purchasing advantages. Obayashi was assigned to the procurement of certain special equipments from Japan, and Fu Tsu was assigned to the procurement of certain batch materials from Taiwan. Those that did not fall into the two categories were jointly purchased following a transparent procedure, and the negotiation efforts were reasonably small. To conclude, the division of procurement and the limited efforts for negotiation indicate a moderate level of needs for procurement autonomy.

• High assessed level of motivation for learning

Although Obayashi led the construction of tunnels and Fu Tsu led the construction of viaducts, both partners considered learning from the other partner, an objective of this JV. Since Fu Tsu, the local partner, had no experience in tunneling, they were highly motivated to learn tunneling techniques from experienced Obayashi. On the other hand, Obayashi aimed to learn the procurement practice, market information, and human resource information in Taiwan to prepare for operating their new business in Mainland China. In order to facilitate their learning, according to the respondents, “they purposely mixed both partners’ employees in work teams and arranged frequent routine meetings before and after work every day so as to not only promptly resolve problems encountered but also provide platforms for learning.” Obviously, the JMJ structure is the one that provides such close working relationship and learning environment.

• Remarks

Based on the analysis of the four determinants, the adoption of JMJ in this JV supports the proposed propositions. Particularly, the low level of cultural difference, high level of trust, and high level of motivation for learning strongly suggest the use of JMJ.

Analysis of C230/C240 JV

The JV in C230 and C240 was formed by Hyundai, the foreign and leading partner, and Chung Lin, the local partner. It turned out that the cooperation among the partners was not very smooth and Chung Lin withdrew their shares and stepped out of the JV one year or so after the project began. The equity share ratio of Hyundai always maintained at above 60%. Even though this JV adopts JMJ, the following analysis shows that SMJ should have been a better choice and could have helped to prevent the dissolution of partnership.

• High assessed level of cultural difference:

The high level of cultural difference is mainly caused by different corporate values. Consistent with the general perception of Korean culture, Hyundai’s management style is more toward collectivism and strong leadership. Some interviewees stated, “Hyundai is so mission-oriented that project performance has much higher priority than individual’s benefits; for example, working overtime voluntarily is considered normal during the period of tight or delayed schedule.” On the contrary, the culture of the local partner is more individualistic. Project needs usually cannot justify the sacrifices of individuals’ rights. Consequently many difficulties in managing the JV were caused by frictions due to cultural difference, such as blames and complaints, coordination problems, lack of motivation, and sense of unfairness. Such high level of cultural difference largely increased the transaction costs, particularly under JMJ.

• Moderate assessed level of trust

The partnering firms had no previous cooperation experiences and reputation was not an important reference since Hyundai was not known as a major international firm and

Chung Lin was only a relatively small construction firm that has little experience in heavy civil construction experiences. According to the interview, “trust was mainly based on credit information.” Compared to other JVs such as those in C210/C215 and C291/296, where partners had much stronger bases for their trust as shown in Table 4, the level of trust between Hyundai and Chung Lin was considered moderate.

• High assessed level of needs for procurement autonomy:

Similar to the arrangement in C210/C215, the procurement included both divided and joint procurements. However, since the local partner was highly concerned with the joint procurement decision, its representing manager was not adequately delegated to make those joint decisions, causing excessively high negotiation efforts. In fact, the high negotiation efforts clearly indicated the needs for more divided procurements, which can be easily achieved under SMJ structure.

• High assessed level of motivation for learning

During the formation of the JV in C230/C240, both parties had relatively strong motivations to learn from each other. As a newcomer in Taiwan’s construction market, “Hyundai is eager to learn Taiwan’s culture, management style, information of local subcontractors, etc.” During the first year’s cooperation, according to Hyundai, “many staffs cooperated with Chung Lin and were well guided by Chung Lin in learning how to conduct business in Taiwan.” Meanwhile, due to its limited experiences in heavy construction, Chung Lin was interested in gaining project experiences and certain skills in tunneling and viaduct construction. It turns out that their high-leveled motivation for learning is the only hypothesized factor that supports the use of JMJ in this JV.

• Remarks

Chung Lin withdrew their shares and stepped out of the JV after one year’s cooperation. Although many other factors may have also contributed to the withdrawal of Chung Lin, this JV is good evidence illustrating the negative impacts on a JV caused by an “inappropriate” choice of governance structure from the model’s perspective. More importantly, if the rival proposition is hypothesized by “the proposed determinants have no impacts on the optimal choice of ICJV control structure,” the dissolution of this JV can be considered evidence that rebuts the rival proposition. Pursuing this further, the governance structure choice in this case should have been SMJ, instead of JMJ. Particularly, the high level of cultural difference and high level of needs for procurement autonomy highly suggest the use of SMJ, even though their motivation for learning suggests JMJ. As a result, the negative impacts on this JV due to the use of opposite control structure serve as contrasting evidence that supports the proposed model.

Analysis of C280 JV

The JV in C280 was formed by two Korean partners, Samsung and Doosan, and a local partner, IE&C, where Samsung was the leading partner. The equity share ratios for Samsung, Doosan and IE&C are 51%, 29% and 20%, respectively. This JV adopts SMJ. • High assessed level of cultural difference

As stated in the interview, “cultural difference is one major reason for this JV to adopt SMJ.” There were considerable disagreements between Samsung and Doosan due to their different engineering backgrounds and specialties as well as the role change in their business relationship. Doosan is the top supplier of power plant equipments in

Korea and has fewer experiences in heavy civil construction. In Korea, the business relationship between Doosan and Samsung was that of a client and contractor. According to the respondent, “the new type of liaison as partnering contractors and their different engineering backgrounds seemed to create considerable difference in terms of corporate values and business practice, such as how to conduct business and how to manage projects.” Such cultural difference was further intensified “by the strong characters presented in the top managers of the two firms.” This case also gives a perfect example in which cultural difference can be significant between partners from the same country.

• Moderate assessed level of trust

Trust among Samsung and IE&C is “based on their good experiences of cooperation in the Taipei Metropolitan Rapid Transit project around ten years ago.” However, since IE&C was only a midsize construction firm in Taiwan, IE&C invited another Korean partner, Doosan, to join the JV, mainly to financially support the project and share the financial risks. As a result, the shares owned by IE&C in the JV were accounted for only 20% of the total equity, the smallest among all. Under such equity structure, IE&C “became wary about the disadvantages due to its weak position in equity shares.” In spite of the relatively high level of trust between Samsung and IE&C, trust in this JV was substantially weakened by the equity structure and the addition of a new partner. • High assessed level of needs for procurement autonomy

This JV was responsible for the construction of 34 km viaducts. The contract was divided into three parts and separately assigned to and managed by each individual partner. For instance, Samsung independently built one prefabrication plant and procured all items and subcontractors for the assigned 13 km viaducts. In addition to the

divided procurements, there were some major joint procurements for two major equipments and concrete aggregates. “These items were jointly procured mainly because of the concern of economies of scale and the joint needs of the special equipments and materials.” Besides, there was another separate small JV formed by Doosan and the local partner IE&C for a prefabrication plant. It is also stated in the interview, “autonomous procurement is very important to individual partner’s profitability and the SMJ structure provides such flexibility for procurement in this JV.” • Moderate assessed level of motivation for learning

During the initial stage of JV formation in C280, all but Samsung considered learning an objective of participating in this JV. Doosan joined the JV with the intention “to learn the local business information and opportunities so as to prepare for future expansion of their power plant equipment business in Taiwan.” Similarly, the local partner IE&C aimed “to learn some advanced construction techniques/management from Samsung.” Samsung, on the other hand, had nothing in particular to learn from other partners, partly because of Samsung’s rich experiences in international projects. However, “because of the problems caused by cultural difference as discussed earlier, they had to forego the adoption of JMJ, which was presumably better for learning.”

• Remarks

The JV in C280 supports the proposed propositions through the use of SMJ given the high level of cultural difference and high level of needs for procurement autonomy.

Analysis of C291/C296 JV

Evergreen, the local partner. The equity share percentages for the two partners were 42% and 58%, respectively. C291/C296 adopts JMJ. It is worth noting that Shimizu, the leading partner but with fewer equity shares, a common practice in construction JVs, confirms that the actual governance is not a strict or automatic consequence of ownership as argued by Geringer and Hebert (1989).

• Low assessed level of cultural difference

In terms of managerial decisions, all partners fully delegated their decision-making rights to their representing managers in the JV board. In terms of corporate values, both partners focused on the overall benefits of a JV and believed that an individual partner’s profit was dependent on the success of the JV. The only minor issue is that “the foreign partner’s exhibition of superiority during communication created some minor problems and uncomfortable atmosphere.”

• High assessed level of trust

Three major reasons contributed to the high level of trust between the partners in C291/C296, even though they had no previous cooperation experiences. First, Shimizu is a highly reputable major international construction firm. Second, Evergreen is one of THSR’s major shareholders. Third, some of the partners’ top managers were old time classmates and good friends. Since their bases of trust were very strong, we consider the level of trust to be high.

• Moderate assessed level of needs for procurement autonomy

In this JV, all decisions for procurement over $60,000 were made jointly and those below $60,000 were made independently. Despite the fact that the level of needs for procurement autonomy may seem low since most procurement decisions were jointly made, we considered the level of needs for autonomy to be moderate. The major reason

is that higher priorities in an open bid competition were given to those bidders who were either recommended by or financially associated with the partnering firms. For example, in C291/C296, the concrete materials were from Japan and recommended by Shimizu, while the steel frames were from an associated business of the largest shareholder, Evergreen.

• High assessed level of motivation for learning

The foreign partners had more advanced skills and technology and were expected to guide the local partner. Evergreen was motivated to learn construction management of international projects and special techniques such as the removal of hazard underground pipes, partly because it was the first time that Evergreen participated in an ICJV. Particularly, according to the interview, “To facilitate the learning, Evergreen purposely assigned key persons, those highly diligent and motivated engineers, to manage the construction work.” On the other hand, for foreign partners, although their motivation may not be as strong as Evergreen, they still hoped to learn how to conduct business in Taiwan. As a result, the level of motivation for learning is considered high.

• Remarks

As we can see, the adoption of JMJ for this JV is consistent with the model prediction. Particularly, the low level of cultural difference, high level of trust, and high level of motivation for learning strongly suggest the use of JMJ.

Analysis of C295 JV

The JV for C295 was formed by the foreign and leading partner, Italian-Thai, together with PEWC, a passive equity holder and the local partner Evergreen. The equity share

percentages for the three partners were 35%, 15%, and 50%, respectively. This JV adopts JMJ. Note that the assessed levels of determinant variables in C295 were identical to those in C291/C296 JV, partly because Evergreen was the major shareholder in both JVs. Since the condition of each determinant variable in C295 is very similar to that in C291/C296, we shall forgo the details. Once again, the assessed levels of determinant variables in C295 strongly suggest the adoption of JMJ, as predicted by the proposed model.

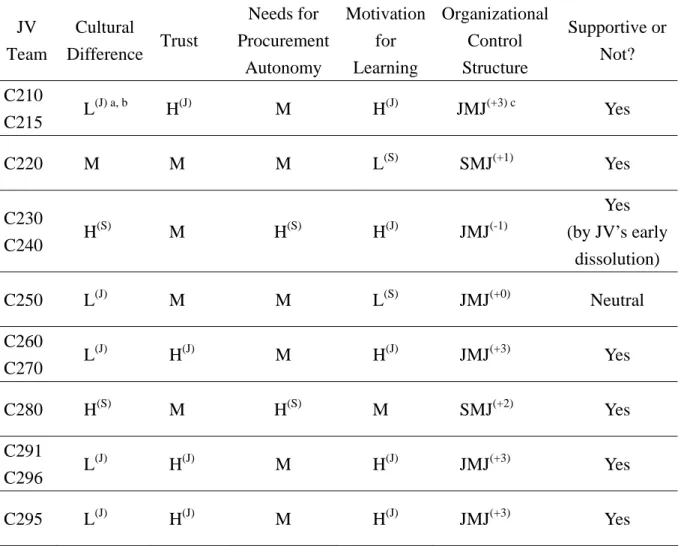

Overall Evaluation of the Model

The purpose of this study is to evaluate empirically the proposed model by examining whether the JVs and their governance decisions in these cases replicate the logic underlying the model. Table 7 summarizes the results tabulated in Tables 3 to 6 and how the model is supported. In this case study, we’ve obtained six JV cases that demonstrate, in our opinion, very strong support for the model. As shown in Table 7, the six JVs are C210/C215, C230/C240, C260/C270, C280, C291/C296, and C295. We’ve also obtained one JV case, C220, that is marginally supportive and one, C250, that is neutral. As shown in Table 7, among the six JVs that strongly support the model, four adopted JMJ, as predicted by the model, one adopted SMJ also as predicted, and the other supports the model by the correlation between the JV’s early dissolution and the JV’s “inappropriate” governance choice. Furthermore, the JVs with marginal and neutral support, C220 and C250, respectively, though showing much weaker support, are by no means contradicting the proposed propositions. As shown in the column “Supportive or Not?” in Table 7, we conclude that the JVs in the THSR project reasonably support the proposed model for the choice of organizational control structure.

[Insert Table 7 here]

7. Conclusions

The ability to make proper decisions for ICJVs is critical to the success of not only international construction firms but also the local firms, which may lead or be invited to join an ICJV in local projects. Among those decisions concerning ICJVs, the choice of governance structure has a profound impact on the JV performance but receives relatively few attentions. This paper empirically evaluates the model proposed in Part (I), which investigates the organizational control choices. The proposed model integrates the transaction cost economics (TCE) view and the resources-based view (RBV). From the TCE perspective, it is hypothesized that a lower level of cultural difference and a higher level of trust will favor the use of JMJ, and vice versa. From the RBV perspective, it is hypothesized that lower needs for procurement autonomy and a higher level of motivation for learning will favor the use of JMJ, and vice versa. In this paper, a case study of a mega transportation project, Taiwan High Speed Rail project (THSR), was conducted to evaluate the proposed model. Using case study as a research methodology, we take the view that case study is an empirical inquiry and an important research methodology in management and social sciences. Through the study of eight ICJVs in THSR project, these cases replicate the linkage between the hypothesized governance determinants and the predicted control structures and reasonably support the proposed model. Lastly, an econometric study can be further conducted in the future to statistically test the proposed model.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We greatly appreciate the help and data offered by the participating professionals from the JV firms of THSR. Financial support from the National Science Council (NSC 95-2221-E-002-321) is gratefully acknowledged.

Table 1. JV Teams/Partners and JV Governance

ICJV Partners and Organizational Control Structures JV Team Foreign Partner Local Partner

(Taiwanese) Organizational Control Structure Project Manager (PM) C210 C215

Obayashi (Japan) Fu Tsu JMJ PM: Obayashi, Vice PM: FuTsu

C220 Daiho (Japan) Chiu Tai Kou Kai

SMJ PM: Daiho. Local partners stepped out due to financial distress

C230 C240

Hyundai (Korea) Chung Lin JMJ PM: Hyundai. Chung Lin withdrew from the JV

C250 Hochtief (Germany) Ballast Nedam (Holland)

Pan Asia JMJ PM: Hochtief, Vice PM: Ballast Nedam and Pan Asia

C260 C270

Bilfinger Berger (Germany)

CEC JMJ PM: Bilfinger Berger, Vice PM: CEC (in C260)

PM: CEC, Vice PM: Bilfinger Berger (in C270)

C280 Samsung (Korea) Doosan (Korea)

IE&C SMJ PM:Samsung, Vice PM: Doosan and IE&C

C291 C296

Shimizu (Japan) Evergreen JMJ PM: Shimizu, Vice PM: Evergreen

C295 Italian-Thai (Thailand)

Evergreen PEWC

JMJ PM: Italian-Thai, Vice PM: Evergreen and PEWC

Table 2. Contracts, Contract Costs and Equity Investment Ratios Contract Contract Costs

(thousand USD )

Equity Investment Ratios

C210 378,788 Obayashi:Fu Tsu=55%:45% C215 561,242 Obayashi:Fu Tsu=55%:45%

C220 369,697 Daiho:Chiu Tai:Kou Kai=40%:30%:30% C230 368,788 Hynudai:Chung Lin =75%:25%

C240 342,930 Hynudai:Chung Lin=80%:20%

C250 686,364 Hochtief:Ballast Nedam:Pan Asia =55%:30%:15% C260 575,151 Bilfinger Berger:CEC=50%:50% C270 653,636 Bilfinger Berger:CEC=50%:50% C280 496,939 Samsung:Doosan:IE&C =51%:29%:20% C291 399,909 Evergreen:Shimizu=58%:42% C295 454,485 Evergreen:Italian-Thai:PEWC=50%:35%:15% C296 80,303 Evergreen:Shimizu=58%:42%