Paper: a study on the certification of the information

security management systems

Andrew Ren-Wei Fung

a, Kwo-Jean Farn

a,b,*, Abe C. Lin

c aInstitute of Information Management, National Chiao-Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu 300, Taiwan, ROC

b

Internet Security Solutions International Co., Taiwan, ROC

c

DCGS for Communications, Electronics and Information(J-6), Ministry of National Defense, Taiwan, ROC Received 7 October 2002; received in revised form 16 January 2003; accepted 20 January 2003

Abstract

Current reliable strategies for information security are all chosen using incomplete information. With standards, problems

resulting from incomplete information can be reduced, since with standards, we can decrease the choices and simplify the

process for reliable supply and demand decision making. This paper is to study the certification of information security

management systems based on specifications promulgated by the Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection (BSMI),

Ministry of Economic Affairs in accordance with international standards and their related organizations. And we suggest a

certification requirement concept for five different levels of ‘‘Information and Communication Security Protection System’’ in

our country, the Republic of China, Taiwan.

D 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Certification; Conformity Assessment Procedure; Information security management system; Standard; Trust

1. Foreword

The Executive Yuan of Republic of China (R.O.C.)

is the highest administration unit in the country. The

Chief of the Executive Yuan is like a premier in

France. In May 2001, the president of R.O.C. ordered

a study on ‘‘National Information and Communication

Infrastructure Security Mechanism Plan.’’ In August,

the president commanded that the National Security

Council should make a proposal on ‘‘The

Establish-ment of the National Plan for Protecting and Assuring

the Critical Information and Communication

Infra-structure,’’ and submitted to the Executive Yuan for

further tasks in order that in information and

commu-nication network resources can be fully used in an

obstacle-free and secure environment by year 2008.

On February 5, 2001, the Executive Yuan of R.O.C

sent out the ‘‘Plan for establishing the construction of

basic information and communications security

mech-anisms in Taiwan’’ to each of its subordinate

author-ities, requesting active cooperation

[1]

, thus officially

turning a new leaf in the development of information

security in Taiwan.

In recent years, several countries (e.g., the USA,

the UK, China, and others) have invested great efforts

in the construction of basic information security

[2 –

0920-5489/03/$ - see front matterD 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S0920-5489(03)00014-X

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 5712301; fax: +886-03-5723792.

E-mail addresses: u8834811@cc.nctu.edu.tw, kjf@iss.com.tw (K.-J. Farn).

4]

, and have added to the impact on Taiwanese society

by the nationwide power outage on July 29, 1999 and

the great earthquake on September 21, 1999. Hence,

the competent authorities in the spring of 1999 began

to realize the importance of security of basic

commu-nication and information construction, and as a result,

they designed ‘‘Security mechanisms in Taiwan’s

basic communication and information construction.’’

Due to the fact that Taiwan’s current communication

and information security measures are restricted by

their limited nature and lack of overall protection,

detection and restorative abilities, the National

Infor-mation Infrastructure Work Group, in an attempt to

efficiently meet the President’s instructions, reviewed

the related plans, and after careful studies, called the

first ‘‘National Information and Communication

Security Meeting’’ on January 31, 2001, trying to

complete the ‘‘Plan for Establishing the Construction

of Basic Information and Communications Security

Mechanisms in Taiwan’’ in 4 years

[5]

.

Before the aforementioned plan was officially

accepted by the Executive Yuan, the number of

people mobilized, the aspects involved and the depth

of interactions with the society were unprecedented

in the field of information security in Taiwan. And

this may have far-reaching effects on the direction

which the information security technologies will take

in the future. According to the plan, the prime

minister and the vice prime minister shall be the

convener and the deputy convener, respectively, of

the ‘‘National Information and Communication

Se-curity Meeting,’’ and the convener of the ‘‘National

Information and Communication Initiative’’ (NICI)

shall be its executive director. The meeting shall set

up seven work groups: an integrated operations work

group, a danger report work group, a technical

support center, an internet crime work group, an

information gathering work group, an audit service

work group and a standard specification work group

responsible for initiating different aspects of the

construction of basic national communications and

information security. Among these work groups, the

Ministry of Economic Affairs takes the main

respon-sibility over the standard specification work group,

with the assistance of the Executive Yuan’s Research,

Development and Evaluation Commission, the

Min-istry of National Defense, the MinMin-istry of

Trans-portation and Communication and the Ministry of

Finance. The main responsibilities are described in

the following:

1. Setting standards for information and

communica-tion security technologies.

2. Setting standards for various institutions for

handling information and communication security

matters.

3. Planning the installation of monitoring technology

for information and communication security.

4. Planning and installing the methods of certification

of information and communication security.

5. Installing the procedure of the information and

communication security.

To achieve the targets of the aforementioned plan,

the BSMI has followed the criteria in Annex 1 – 3 to

the Agreement of Technical Barriers to Trade in the

Uruguay round of multilateral trade negotiations:

1. Formulating in the standards for Evaluation criteria

for IT security (ISO/IEC 15408), Code of practice

for information security management (ISO/IEC

17799), and Software Process Assessment (ISO/

IEC TR 15504).

2. Developing protection profiles of different

prod-ucts in the ISO/IEC 15408 series of standards (e.g.,

access control, cryptography, issue and

manage-ment of Public Key Certificates) and the

installa-tion of their common monitoring techniques.

Table 1

Ten CISSP information systems security test domains are covered in the examination pertaining to the common body of knowledge[8]

Item Knowledge domain

1 Security management practices 2 Access control systems 3 Telecommunications and network security 4 Cryptography 5 Security architecture and models 6 Operations security 7 Applications and systems

development

8 Business continuity planning and disaster

recovery planning

9 Law, investigations, and ethics 10 Physical security

3. Making BS7799-2 (Information Security

Manage-ment Part 2: Specification for Information Security

Management Systems) a national standard, and

installing a certification system for Taiwan’s

communication and information security

manage-ment systems.

4. Installing procedures for communication and

information security management systems

accred-itation and product certification and accredaccred-itation

as well as laboratory accreditation in compliance

with the requirements in ISO/IEC Guide 62, ISO/

IEC Guide 65 and ISO/IEC 17025.

The BSMI is in the process of promoting all the

related tasks. This study briefly analyses the

differ-ences and similarities among certification of

informa-tion security management systems, quality

manage-ment systems and environmanage-mental managemanage-ment systems

in Sections 2 and 3 propose a concept for fundamental

certification standards according to various the risk

Table 2

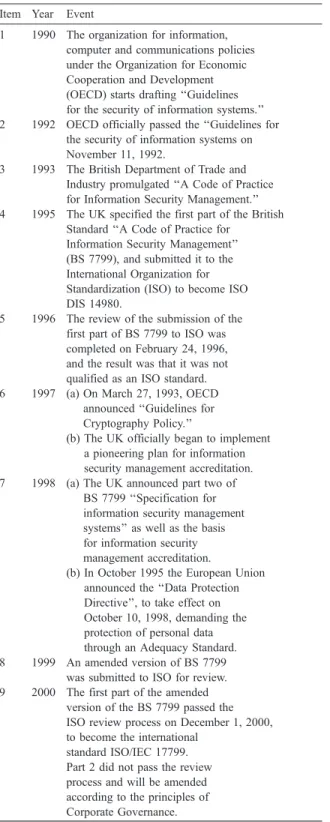

Brief history of information security management accreditation Item Year Event

1 1990 The organization for information, computer and communications policies under the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) starts drafting ‘‘Guidelines for the security of information systems.’’ 2 1992 OECD officially passed the ‘‘Guidelines for

the security of information systems on November 11, 1992.

3 1993 The British Department of Trade and Industry promulgated ‘‘A Code of Practice for Information Security Management.’’ 4 1995 The UK specified the first part of the British

Standard ‘‘A Code of Practice for Information Security Management’’ (BS 7799), and submitted it to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) to become ISO DIS 14980.

5 1996 The review of the submission of the first part of BS 7799 to ISO was completed on February 24, 1996, and the result was that it was not qualified as an ISO standard. 6 1997 (a) On March 27, 1993, OECD

announced ‘‘Guidelines for Cryptography Policy.’’

(b) The UK officially began to implement a pioneering plan for information security management accreditation. 7 1998 (a) The UK announced part two of

BS 7799 ‘‘Specification for information security management systems’’ as well as the basis for information security management accreditation.

(b) In October 1995 the European Union announced the ‘‘Data Protection Directive’’, to take effect on October 10, 1998, demanding the protection of personal data through an Adequacy Standard. 8 1999 An amended version of BS 7799

was submitted to ISO for review. 9 2000 The first part of the amended

version of the BS 7799 passed the ISO review process on December 1, 2000, to become the international

standard ISO/IEC 17799. Part 2 did not pass the review process and will be amended according to the principles of Corporate Governance.

Table 2 (continued) Item Year Event

10 2001 (a) On September 11 and 12, 2001, OECD in Tokyo asked the establishment of information security standards for each specific industry, in addition to the original ISO/IEC 17799 basic standards. A task force was formed to work out the information security guideline.

(b) The UK announced BS7799-2: 2002 Draft in November 2001, publicly soliciting opinions, asking user organizations to submit their opinions prior to March 31, 2002 for integration. The amended version of BS7799-2 is set to be announced in June, 2002. 11 2002 (a) On July 25, 2002, OECD published

‘‘OECD Guidelines for the Security

of Information Systems and Networks—Towards a Culture of Security.’’ Replacing the old version of November 26th, 1992.

(b) On September 5, 2002, BS 7799-2:2002 version was also revised according to the aforementioned guide.

12 2003 Information security management certification is likely to become official ISO standard 17799.

Apart from the Australia, Brazil, Czech Republic, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, UAE, the UK have currently agreed to adopt BS 7799.

classification in Taiwanese certification preparatory

work. Section 4 describes the conclusion.

2. The brief introduction of related information

security management specifications

The work to establish international approval

proce-dures for information security management

accredita-tion in the digital society can be traced back to

November 1988. How should the Common Body of

Knowledge (CBK) of the specialized personnel

work-ing with information security be accredited? An

organ-ization specialized in the accreditation of information

security personnel, the International Information

Sys-tem Security Certification Consortium (ISC)

2was

established in Salisbury, England. To be approved by

the (ISC)

2, one requires tests of 10 major CBK

categories as in

Table 1

(taking normally 6 h to answer

250 multiple-choice questions). Correct answers to

70% of the questions in combination with a minimum

of 3 years working experience with information

secur-ity related matters are needed to qualify as a Certified

Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP).

CISSP certification is not issued on a permanent basis,

but the test must be taken once every 3 years, and only

after passing the test will the person get a renewed

certificate. The Canadian Information Processing

Soci-ety (CIPS), the Computer Security Institute (CSI), and

the Information Systems Security Association (ISSA)

all recognize CISSP certification. Apart from (ISC)

2,

SANS and other organizations also have their series of

accreditation tests for specialized information security

techniques (e.g., UNIX Security, Intrusion Detection

Systems). Apart from the certification of specialized

information security personnel, the work to set the

international standards for the specifications for the

management of information systems security is in

progress

[6,7]

.

Table 2

gives a brief history of its

development, and

Table 3

gives an outline of its

contents as submitted to ISO after amendments.

The ideas behind and the structure of the

specifi-cations for information security management

certifi-cation are the same as for ISO 14001, as shown in

Fig. 1

. Systematized security concepts such as main

requirements, goal management, risk prevention, law

obedience, and continuous improvement are

imple-mented according to a Plan – Do – Check – Action (P –

D – C – A) cycle as shown in

Fig. 2

. Since risk

appraisal includes all organizations and all

depart-ments, areas, staff and activities, the rationality and

conformity of the appraisal is still a topic for research

[9]

. Compared to ISO 14001, it is more difficult.

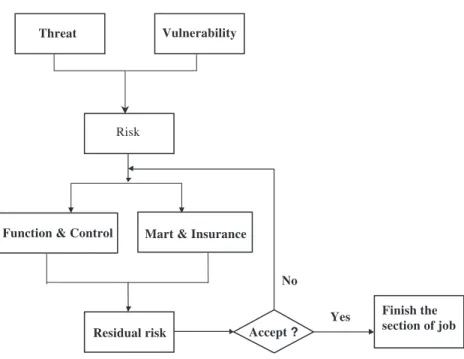

Fig. 3

is a graphic explanation of the information security

management risk appraisal process. The risk

manage-ment procedure in this figure-risk analysis aimed at risk

extent definition and risk recognition and estimation,

risk evaluation to decide project risk tolerability

poli-cies and responses and risk minimization and control

when setting project policies—are based on

implemen-tation and audit.

Fig. 4

is a schematic explanation of the

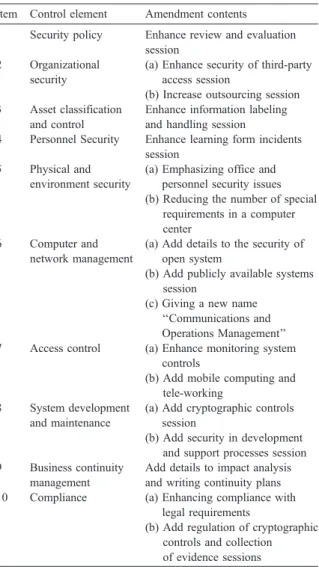

Table 3

The outline of amendments to BS7799 contents[6]

Item Control element Amendment contents 1 Security policy Enhance review and evaluation

session 2 Organizational

security

(a) Enhance security of third-party access session

(b) Increase outsourcing session 3 Asset classification

and control

Enhance information labeling and handling session

4 Personnel Security Enhance learning form incidents session

5 Physical and environment security

(a) Emphasizing office and personnel security issues (b) Reducing the number of special

requirements in a computer center

6 Computer and network management

(a) Add details to the security of open system

(b) Add publicly available systems session

(c) Giving a new name ‘‘Communications and Operations Management’’ 7 Access control (a) Enhance monitoring system

controls

(b) Add mobile computing and tele-working

8 System development and maintenance

(a) Add cryptographic controls session

(b) Add security in development and support processes session 9 Business continuity

management

Add details to impact analysis and writing continuity plans 10 Compliance (a) Enhancing compliance with

legal requirements

(b) Add regulation of cryptographic controls and collection of evidence sessions

Fig. 1. Systematized security concepts.

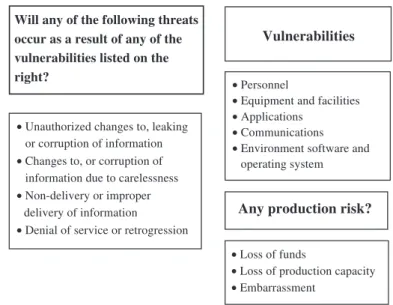

Fig. 3. Risk analysis and risk assessment flow chart and explanation.

Fig. 4. Schematic explanation of communication and information security management risk appraisal. This diagram is cited and revised from Bsi BS7799 ‘‘Lead Auditor Course.’’

risk management process

[10,11]

. Under normal

cir-cumstances, the risk created by a security incident is the

monetary and production loss brought to each piece of

information and assets by all threats through all weak

points, and the totality of all kinds of risk to the

organizational embarrassment. We use ISO/IEC TR

13335 methodology

[12]

to establish the risk

manage-ment classification.

The four threats in

Fig. 3

are in BS7799 abbreviated

to threats C, I and A, as shown in

Table 4

, and the

British Standards Institution (BSI) further integrates

the compliance requirements described in the

follow-ing designated L. as described in detail in

Table 5

. The

use of the C, I, A and L threat categories will allow a

more efficient choice of control targets and response

policies for the Information Security Management

System (ISMS).

Threat: information security related to any

opera-tional function, process or activity can be threatened in

many ways. The banking industry has already defined

four specific threats, which, if they occur, will weaken

trust or completeness of operational functions, products

or services or disturb operational sustainability.

The following table provides explanations for each

of these four threats:

Vulnerability: ‘‘vulnerability’’ refers to the ways by

which a threat occurs.

The following table explains these vulnerabilities:

Table 4

Information security characteristics

1. Confidentiality (C): Guarantees that the data only can be accessed by authorized personnel.

2. Integrity (I): Safeguarding of the accuracy and completeness of data and data processing methods.

3. Availability (A): Guarantees that data can be accessed through authorized personnel and used when needed.

Table 5

BS7799 integrates the compliance requirements[6,7]

(1) Compliance with legal requirements (ISO/IEC 17799: 2000(E), 12.1):

Objective: To avoid breaches of any criminal and civil law, statutory, regulatory or contractual obligations and of any security requirements.

(2) Reviews of security policy and technical compliance (ISO/IEC 17799: 2000(E), 12.2):

Objective: To ensure compliance of systems with organizational security policies and standards.

(3) System audit considerations (ISO/IEC 17799: 2000(E), 12.3): Objective: To maximize the effectiveness of and to minimize

interference to/from the system audit process.

Threat Explanation Unauthorized changes to,

leaking or corruption of information

This threat is made up of intentional or non-intentional release of information and intentional additions, changes or corruptions to information by the staff accessing or not accessing information processes in its normal dispensation of duties. Changes to,

or corruption of information due to carelessness

This threat is made up of loss, addition, change or corruption of information due to carelessness, oversight or unintentional action. The possibility of this threat occurring arises out of human action or non-action, hardware, software or communication failure and natural disasters. Non-delivery

or improper delivery of information

This threat is made up of information being unintentionally deleted or improperly delivered due to paper or digital formats. This includes hardware, software and communication failure and natural disasters.

Denial of service or retrogression

This threat is made up of insufficient usability as a result of unplanned short-term or long-term retrogression occurring in the overall workflow or in part of the workflow.

Vulnerability Explanation

Personnel This vulnerability is attributed to the staff, manufacturers and hired personnel. When not understanding or obeying the department operational procedure and control. Equipment and

facilities

This vulnerability is caused by the practical security of the work area and equipment, and the access to work area and equipment.

Risk categories: there are three main risks that must

be considered during risk appraisal.

The following table explains these risk categories:

3. Information security management system

certification and accreditation mechanisms

Owing to the speed with which quality and

envi-ronmental management certification has developed in

Taiwan, quality or certification is not standardized.

This could easily have a negative impact on trades,

and the Ministry of Economic Affairs on March 5,

1997, set and issued BCIQ order 86350708

‘‘Imple-mentation Rules for the Chinese Quality Management

and Environmental Management Accreditation

Sys-tem,’’ and on March 26 of the same year, it set and

issued BCIQ order 86260244 ‘‘Points for the

Estab-lishment of the Chinese National Accreditation

Board.’’ On July 30, 1998, the Chinese National

Accreditation Board (CNAB) began accepting

appli-cations for accreditation from relevant certification

organizations and organizations training inspection

personnel. Based on the definition in the Article 4 in

the above-mentioned implementation rules:

1. Accreditation: The authority in charge issues an

official written recognition that the certification or

training organization is capable of implementing

the regulated work processes or activities.

2. Certification: The certification organization issues

a written guarantee that the inspectors, products,

procedures or services comply with the procedures

or activities specified in the regulations.

In response to the needs for certification of

profes-sional safety and health, fire security equipment and

information security management systems, the

Minis-try of Economic Affairs on March 3, 2001, set and

issued MOE (90) Accreditation 0900460122

‘‘Imple-mentation Regulation for Chinese National

Accredita-tion Scheme.’’ Apart from the original quality and

environmental management, regular certification

organizations (e.g., organizations for the certification

of information security management systems) and the

accreditation of product certification and inspection

organizations are all the responsibility of the CNAB.

On March 2, 2001, MOE (90) Accreditation document

no. 09003504120 was issued, announcing the

amend-ment of the ‘‘Points for the Establishamend-ment of the

Chinese National Accreditation Board.’’ In other

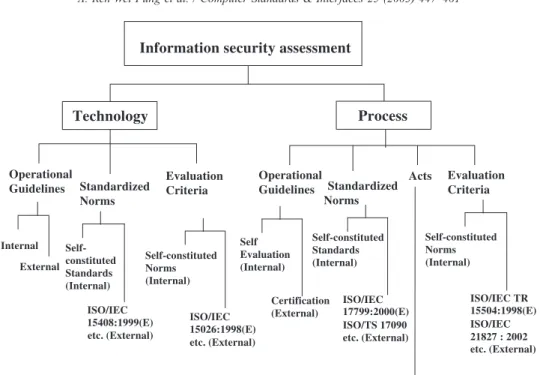

words, as

Fig. 5

shows, the agreement on technical

trade barriers in the General Agreement on Tariff and

Vulnerability Explanation

Applications This vulnerability is caused by a company’s procedures for the processing of information. Application involves the handling of input and output.

Communications This vulnerability occurs during the electronic transfer of information between two stations. Environment

software and operating system

This vulnerability occurs in the operating system and sub-systems at the location where the application software was developed and is used.

Risk categories Explanation

Loss of funds Loss of funds is defined as the loss of valuable objects or increased costs or expenses. The category business function risk will increase with the increased risk of fund losses or potential value Example Valuable objects – money – bonds – capital transfers Increased costs: – bond issue – theft

– negative legal decision, etc. Loss of

production capacity

When the staff is unable to continue carrying out its duties or when duties must be repeated, loss of production capacity will occur. When business functions can no longer be used, or when results are incorrect, work will be interrupted or repeated. Organizational

embarrassment

This risk category considers the impact on public trustworthiness confidentiality, accuracy and consistency must also be considered.

Trade (GATT) demands that each country, considering

safety, health, environment and consumer protection

factors, set technical laws or standards, and proves that

related products conform to the Conformity

Assess-ment Procedure (CAP) of these technical laws or

standards and that they do not create any unnecessary

barriers to international trades. Due to the lack of

integrity and secure reliability of information,

e-com-merce and e-governments turning to

digitization/Inter-net will never become active, and the virtual world will

never go beyond cultural recreations and advertising

framework. Services for the accreditation, certification

Fig. 5. The information security assessment explanation.

and inspection of information security mechanisms

establishing an international digitized/Internet society

has been directed by the CNAB since March 2, 2002.

According to BSMI plans, ISMS accreditation and

certification as shown in

Fig. 6

, is set to begin in March

2002.

There will be different security demands on

infor-mation systems due to different working conditions,

e.g., the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s

(FDIC) Division of Supervision (DOS) proposed a

set of Electronic Banking Safety and Soundness

Examination Procedures (S&S Exam.) aimed at

differ-ences in the characters of Internet banking services

provided by financial institutions and the extent of

risks faced, clearly dividing them into three different

levels as shown in

Table 6 [13]

. Based on the

manage-ment concepts shown in

Table 7 [14]

, ‘‘Maturity of

Information Risk Management’’ and ‘‘Risk Category

Table 6

U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance (FDIC) Division of Supervision (DOS) proposed a set of Electronic Banking Safety and Soundness Examination Procedures[13]

Level Electronic banking functional explanation 1 Information-only systems

2 Electronic information transfer systems 3 Fully transactional information systems

Table 7

Maturity of information risk management[14]

Maturity level Description

0 Non-existent: management processes are not applied at all

(a) No risk assessment of processes or business decisions. The organization does not consider the business impact associated with security vulnerabilities. Risk management has not been identified as relevant to IT solutions and services;

(b) The organization does not recognize the need for IT security. Responsibilities and accountabilities for security are not assigned. Measures supporting the management of IT security are not implemented. There is no IT security reporting or response process for IT security breaches. No recognizable security administration processes exist; (c) No understanding of the risks, vulnerabilities and threats to IT operations or service continuity by management. 1 Initial/Ad-Hoc: processes are ad-hoc and disorganized

(a) The organization consider IT risks in an ad hoc manner, without following defined processes or policies. Informal project based risk assessment is used;

(b) The organization recognizes the need for IT security, but security awareness depends on the individual. IT security is reactive and not measured. IT security breaches invoke ‘finger pointing’ responses if detected, because responsibilities are unclear. Responses to IT security breaches are unpredictable;

(c) Responsibilities for continuous service are informal, with limited authority. Management is becoming aware of the risks related to and the need for continuous service.

2 Repeatable but intuitive: processes follow a regular pattern

(a) There is an emerging understanding that IT risks are important and need to be considered. Some approach to risk assessment exists, but the process is still immature and developing;

(b) Responsibilities and accountabilities for IT security are assigned to an IT security coordinator with no management authority. Security awareness is fragmented and limited. Security information is generated, but is not analyzed. Security tends to respond reactively to incidents and by adopting third-party offerings, without addressing the specific needs of the organization. Security policies are being developed, but inadequate skills and tools are still being used. IT security reporting is incomplete or misleading;

(c) Responsibility for continuous service is assigned. Fragmented approach to continuous service. Reporting on system availability is incomplete and does not take business impact into account.

3 Defined process: processes are documented and communicated

(a) An organization-wide risk management policy defines when and how to conduct risk assessments. Risk assessment follows a defined process that is documented and available to all staff;

(b) Security awareness exists and is promoted by management through formalized briefings. IT security procedures are defined and fit into a structure for security policies and procedures. Responsibilities for IT security are assigned, but not consistently enforced. An IT security plan exists, driving risk analysis and security solutions. IT security reporting is IT focused, rather than business focused. Ad hoc intrusion testing is performed;

(c) Management communicates consistently the need for continuous service. High-availability components and system redundancy are being applied piecemeal. An inventory of critical systems and components is rigorously maintained.

Management’’ and referring to the regulations in other

countries

[12,15]

, we categorize our ISMS

certifica-tion into five categories as shown in

Table 8

, where

category 3 and above connects to the certification of

the international BS7799-2. Category 4 is designed to

take different industry demands into consideration.

Table 7 (continued)

Maturity level Description

4 Managed and measurable: processes are monitored and measured

(a) The assessment of risk is a standard procedure and exceptions would be noticed by IT management. It is likely that IT risk management is a defined management function with senior level responsibility. Senior management and IT management have determined the levels of risk that the organization will tolerate and have standard measures for risk/return ratios;

(b) Responsibilities for IT security are clearly assigned, managed and enforced. IT security risk and impact analysis is consistently performed. Security policies and practices are completed with specific security baselines. Security awareness briefings, user identification, authentication and authorization have become mandatory and

standardized. Intrusion testing is standardized and leads to improvements. Cost/benefit analysis, is increasingly used. Security processes are coordinated with the overall organization security function and reporting is linked to business objectives;

(c) Responsibilities and standards for continuous service are enforced. System redundancy practices, including use of high-availability components, are being consistently deployed.

5 Optimized-best practices are followed and automated

(a) Risk assessment has developed to the stage where a structured, organization-wide process is enforced, followed regularly and well managed;

(b) IT security is a joint responsibility of business and IT management and integrated with corporate business objectives. Security requirements are clearly defined, optimized and included in a verified security plan. Functions are integrated with applications at the design stage and end users are increasingly accountable for managing security. IT security reporting provides early warning of changing and emerging risk, using automated active monitoring approaches for critical systems. Incidents are promptly

addressed with formalized incident response procedures supported by automated tools. Periodic security assessments evaluate the effectiveness of implementation of the security plan. Information on new threats and vulnerabilities is systematically collected and analyzed, and adequate mitigating controls are promptly communicated and implemented. Intrusion testing, root cause analysis of security incidents and proactive identification of risk is the basis for continuous improvements. Security processes and technologies integrated organization wide;

(c) Continuous service plans and business continuity plans are integrated, aligned and routinely maintained. Buy-in for continuous service needs is secured from vendors and major suppliers.

Table 8

The classification of certification in the ISMS

Categories Requirements for certification

1 (a) Compliance with legal requirements (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.10.1). (b) Security policy (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.1).

(c) Asset classification and control (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.3). (d) Protection against malicious software (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.6.3). (e) Security in development and support processes (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.8.5). 2 (a) Requirements for Categories 1.

(b) Compliance (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.10). (c) Organizational security (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.2). (d) User training (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.4.2).

(e) Responding to security incidents and malfunctions (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.4.3). (f) Business continuity management (BS 7799-2: 1999, 4.9).

3 Requirements for BS 7799-2:2002 Annex A.

4 Requirements for BS 7799-2:2002 Annex A as well as requirements for different industries as shown inFig. 8. 5 Requirements for TQM (Total quality management, included BS 7799-2).

Category 5, apart from the requirements in BS7799-2,

also has to consider the integrity of information

security management systems and quality and

envi-ronmental management systems. On the other hand,

category 3 or above should apply the market and

insurance mechanisms shown in

Fig. 7

and

Table 9

and reinforce the shortcomings of ISO/IEC 17799

shown in

Fig. 8

.

Fig. 9

shows a reference flowchart

Fig. 7. Example of the application of risk analysis in the market and insurance mechanisms.

Table 9

The application of information security in the market and insurance mechanisms[16]

Provider Policy Min. Coverage premium Notes limits Source Cigna property and casualty Secure systems insurance $25,000 $25,000,000 Requires security assessment by approved vendor Mello (1998) ICSA (International Computer Security Association)

TruSecure $20,000 $250,000 Requires ICSA security review

Attrino (1998), Weise (1998) J&H March NetSecure $5,000 $200,000,000 Requires E-business

security assessment

netsecure.com(2000) Lloyds CIDSI (Computer

Information and Data Security Insurance)

$10,000 $50,000,000 Policy has Information Risk Group (IRG) as a required element Koehn (1998) Reliance national/NRMS InsureTRUST $10,000,000 Requires NRMS (Network Risk Mgt Services of Atlanta) review Weise (1998) Zurich Financial Services Group

E-risk protection program $4,000 $25,000,000 Requires IBM security certification

O’D. Moore (1999) This figure covers the cost of the security review.

Fig. 9. Selection methods for ISMS protection[12].

of the decision procedure for the choice of

informa-tion security management preventive measures

[12]

.

4. Conclusion

The main goal of international standardization is to

create a trade environment providing each of the

fol-lowing functions to promote the exchange of products.

1. Product quality and reliability and price

concord-ance.

2. Guaranteeing the user’s security and promoting the

recycling of resources.

3. Goods, technology and service interoperability and

mutual sequential continuity.

4. Simplification to reduce molding for a greater

production capacity to reduce cost.

5. Simplification in order to diminish the frequency of

modeling in the hope of expanding production

scope and lower cost.

6. Improving the convenience of repair and

main-tenance and distribution efficiency.

In 1906, the beginnings of electrical technology

started and in October 4, 1946, an international

meet-ing was held in London, England, to promote

interna-tional unification and adjustment of industrial

standards officially and to establish the International

Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO began

operating on February 23, 1947. October 14 is

there-fore also known as World Standards Day

[18]

.

The so-called standards are unified regulations and

simplified necessary timely conditions that provide a

way of measuring objects, functions, installations,

states, actions, control procedures, user instructions,

work procedures, responsibilities and duties, concepts

of power, and so on, based on fair, just, and

conven-ient opinions. These specifications are the technical

specifications in these standards that are directly or

indirectly related to the quality of products or services.

Normally, specifications or standards often pose

dif-ferent demands because of difdif-ferent types of

organ-izations

Tables 7 and 8

offer schematic explanations.

The standards for implementing P – D – C – A cycle in

ISMS, as shown in

Table 10

.

The certification standards are proposed in the third

section of this paper regarding the ability of Taiwan’s

information security management systems (levels 1 –

5) to meet the international systems (levels 3 – 5)

demands on functional standards for certification

specifications for relevant information technology on

different types of organizations still need to be further

researched

[19]

.

Global civilization experienced great changes in

the 1990s. Quality, environmental, safety and health

management gradually moved towards conformity

and standardization, and related international

stand-ards also affected the economic development in many

nations, as well as their organizational management

and operations. The best evidence of this is the

abidance by the ISO 9000 series of standards for

quality management and the ISO 14000 series of

standards for environmental management.

Interna-tional standards for information security management

issued in the last month of the 20th Century have

become a guide for the construction of a reliable

information environment. If appropriately used, this

will not only improve the security of information

systems, but it will also help shape a culture of quality.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to the

reviewers for their suggestions and comments. Their

input have greatly upgraded our paper.

Table 10

The international ISMS standards in risk management cycle Risk management level Requirements for risk level Cycle Categories Plan ISO/IEC TR 13335 Do 1 ISO/IEC 17799 2 ISO/IEC 17799 3 ISO/IEC 17799 4 ISO/IEC 17799 plus industry-related standards (e.g., Health informatics—Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) must comply with ISO/TS 17090, too) 5 The integration of ISO/IEC 17799,

industry-related standards,

ISO 9000, and ISO 14000 into ISMS Check BS 7799-2:2002

References

[1] The Executive Yuan of Republic of China (R.O.C.), February 5, 2001 (90) MOE document no. 007431 (2001).

[2] The White House, National Plan for Information Systems Protection Version 1.0 (2000) 101 – 102.

[3] F.B. Schneider, Trust in Cyberspace, National Academic Press, New York, U.S.A., 1999.

[4] A. Rathmell, Protecting critical information infrastructures, Computers and Security 20 (2001) 43 – 52.

[5] National Information Infrastructure Group (NII), the Execu-tive Yuan of R.O.C., The first meeting of the National infor-mation and communication security meeting (meeting data). National Information Infrastructure Group, Executive Yuan, (2001).

[6] ISO (International Organization for Standardization)/IEC (In-ternational Electro-technical Commission), Information Tech-nology—Code of Practice for Information Security Manage-ment. ISO/IEC 17799. 2000 (E), ISO, (2000).

[7] BSI (British Standards Institution), Information Security agement—Part 2: Specification for Information Security Man-agement Systems. BS7799-2:1999; Information Security Management Systems - Specification with guidance for use. BS7799-2:2002, BSi (2002), September, London.

[8] R.L. Krutz, R.D. Vines, The CISSP Prep Guide: Mastering the Ten Domains of Computer Security, Wiley, Washington, D.C., U.S.A., 2001.

[9] Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection, MOE, col-lected papers from the APEC-SBS Seminar, September 22, 2001, Taipei City, Bureau of Standards, Metrology and In-spection, Ministry of Economic Affairs (2001).

[10] IEC, Dependability Management—Part 3: Application Guide-Section 9: Risk Analysis of Technology Systems. IEC 300-3-9, 1995, IEC (1995).

[11] ISO, Banking, Securities and Other Financial Services—Infor-mation Security Guidelines. ISO TR 13569: 1997(E), ISO (1997).

[12] ISO, Information Technology—Guidelines for the Manage-ment of IT Security, Parts 1 – 5. ISO/IEC TR 13335 (All Parts), ISO (2001).

[13] U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Division of Supervision. Electronic Banking: Safety and Soundness Ex-amination Procedures (1998).

[14] P. Williams, Information security governance, Information Se-curity Technical Report 6 (3) (2001) 60 – 70.

[15] B. Solms, R. Solms, Incremental information security certifi-cation, Computers and Security 20 (4) (2001) 308 – 310. [16] R.C. Reid, S.A. Floyd, Extending the risk analysis model to

include market-insurance, Computers and Security 20 (4) (2001) 331 – 339.

[17] OECD Workshop, OECD Workshop Information Security in a Network World, 12 – 13, September 2001, Tokyo, Japan. [18] C. Shu-The, A study into the internationalization of national

standards. Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection, Ministry of Economic Affairs, 1990.

[19] ISO, Health informaticsUPublic Key Infrastructure Part 1 – 3, ISO/TS 17090 (All Parts), ISO, 2002.

Andrew Ren-Wei Fung received his BBA and MS degrees in Information agement from the National Defense Man-agement College, Taiwan, in 1987 and 1995, respectively. He is currently a PhD candidate at the Institute of Information Management, National Chiao Tung Uni-versity (NCTU), Hsinchu, Taiwan. His re-search interests include Information Security and Parallel Computing.

Kwo-Jean Farn is director of the R&D Department at Taiwan Internet Security Solutions, Co. and a part-time associate professor at the National Chiao Tung Uni-versity (NCTU) in Taiwan. He received his PhD degree in 1982. His extensive experience includes a 20-year career in Information Technology and a 10-year career in Information Security. He served as chair of the Implementation Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Proj-ect at Computer and Communications Research Laboratories/Indus-trial Technology Research Institute (CCL/ITRI) in Taiwan from 1999 to September 2000. He has worked at ITRI for more than 18 years until the summer of 2001. He holds eight patents in the area of Information Security.

Lieutenant General Abe C. Lin was appointed as Deputy Chief of General Staff for Communications, Electronics and Information (J-6) of the MND on March 1, 2002. J-6 directs and oversees the policy of C4ISR, Electronic and Infor-mation Warfare, Communications, and Information security of the Republic of China on Taiwan. In the year 2000, the Government of Taiwan appointed Gen. Lin to the post of Deputy executive Sec-retary of the National Information and Communications Initiatives (NICI) of the Government of Taiwan. In an additional capacity, Gen. Lin has been facilitating the establishment of a national-level network security infrastructure. General Lin, who graduated from Taiwan Air Force Academy in 1970, earned his Master’s Degree in Business Administration from the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, and his Master’s Degree in Electrical Engineering from the University of Illinois. He has also published numerous papers and dissertations to express his ideas. These papers have received strategic attention from the Government of Taiwan and the academia.

![Fig. 8. The use of ISO/IEC 17799 in various industry information security management standards [17] .](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7723794.147115/13.816.127.682.552.963/fig-iso-various-industry-information-security-management-standards.webp)