Factors Affecting Students’ Evaluation

in a Community Service-Learning Program

KAI-KUEN LEUNG1,*, WEN-JING LIU1, WEI-DAN WANG2 and

CHING-YU CHEN1

1

Department of Family Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital and National Taiwan University College of Medicine, No. 7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 10016, Taiwan, R.O.C.; 2Department of Social Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei No. 7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 10016, Taiwan, R.O.C. (*author for correspondence, Fax: +886-2-2311-8674; E-mail: kkleung@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw)

Received 15 December 2005; accepted 30 April 2006

Abstract. A community service-learning curriculum was established to give students opportu-nities to understand the interrelationship between family and community health, the differences between community and hospital medicine, and to be able to identify and solve community health problems. Students were divided into small groups to participate in community health works such as home visits etc. under supervision. This study was designed to evaluate the community service-learning program and to understand how students’ attitude and learning activities affected students’ satisfaction. The results revealed that most medical students had a positive attitude towards social service and citizenship but were conservative towards taking the role to serve people in the community. Students had achieved what they were required to learn especially the training in communication skills and ability to identify social issues. Students’ attitude towards social service did not affect their opinions on the quality of the program and subjective rating on their achievement. The quality of the program was related to the quality of learning rated by the students.

Key words: attitude, community medicine, evaluation, service learning

Introduction

The mission of medical school includes cultivating medical students towards meeting the contemporary and prospective health-related needs and demands of society (Boelen, 1995). However, it has been recognized that medical education in North America has not met these goals (Petersdorf and Turner, 1995). The shortcomings of the American medical education system have also been noted in Taiwan. Medical education in Taiwan is fragmented, techni-cally oriented, overemphasizing on subspecialty training, and failing to ad-dress the needs of the general population.

Over the past decade, changes in medical education have been underway in Europe and North America, aiming to improve the training of physicians. One of these changes emphasizes ambulatory and community medical training, along with training in working with people in the community (Petersdorf and Turner, 1995). To become community-responsive physicians, medical stu-dents need to spend time within communities, learn community health issues from local people, and contribute to community health within and beyond the provision of clinical care (Brill et al., 2002; Rubenstein et al., 1997). The importance of adjusting medical education goals to meet community needs and the use of communities as a learning site has been emphasized over the past decade (Boelen, 1995; Bruce, 1996; Gupta and Spencer, 2001; Habbik and Leeder, 1996; Morrison and Wat, 2003; Petersdorf and Turner, 1995). Service-learning is one strategy for enabling students to learn community needs and to develop social responsibilities (Eckenfels, 1997).

Service Learning

Service-learning is a form of education in which students engage in activities that address human and community needs together with structured oppor-tunities intentionally designed to promote student learning and development (Jacoby,1996).

Service-learning has been implemented in many medical schools as an educational approach that combines community service with explicit learning objectives, structured learning, student and faculty preparation, and oppor-tunities for student reflection (Honnet and Poulsen,1989; Seifer, 1998). The purpose of service-learning is to prepare students to be responsive to com-munity issues, to be aware of the need for competent comcom-munity health care, to understand the need to develop relationships between communities and academic institutions, to foster a sense of citizenship, and to promote social change (Faller et al., 1995).

There are many community service programs in medical schools in Tai-wan. Most of these service-learning programs have been initiated by student groups aiming to provide education and assistance to medically underserved communities, especially aboriginal villages. Usually, these community pro-grams are not part of a formal medical school curriculum and lack appro-priate design and evaluation. Learning in these programs has been arbitrary. Students do not have formal opportunities for self-reflection and receive little preparation, guidance, or evaluation from faculty members.

Program Description

Medical schools in Taiwan admit qualified high school graduates into a 7-year medical education program. Traditionally, the first 4 years are for college

equivalent and basic medical education courses. The fifth and sixth years are for clinical medical education courses, and the seventh year is for a rotating internship. The National Taiwan University College of Medicine (NTUCM) launched its first community-service curriculum in 1999. This program was precipitated in part by a major earthquake in Taiwan on September 21, 1999 that caused tremendous damage island-wide. The objectives of this service-learning oriented community medicine course are as follows: (1) to understand the scope and diversity of issues in community medicine; (2) to understand the relationship between health issues and the community’s physical, cultural, economical, and social environment; and (3) to be able to identify community health problems and apply classroom medical knowledge to solve them.

The community service-learning program is designed and organized through the joint effort of community health centers, local practitioners, and the departments of family medicine and social medicine of NTUCM. Tutors include NTUCM faculty members, senior family medicine residents and local health professionals. Tutors coordinate all community service-learning activities, give prompt feedback to students, keep students engaged in their work, and ensure a safe learning environment.

Before community placement, students receive 2 weeks of training in the form of lectures, small group discussions, and bedside and OPD training in clinical skills. Topics in this 2-week course include principles in community medicine, medicine and society, ethics in primary health care, adolescent health care, doctor–patient communication, community health service, family health assessment, bio-psycho-social health care, community pre-ventive practice, stress management, geriatric health care, traditional and alternative medicine, introduction to medical care systems, health care poli-cies and national insurance, and telemedicine.

During this course, students were divided into small groups of five–six people for community service training in one of two pre-selected communities (the Lu-Ku disaster area or the Dou-Liou community) for 4 weeks. All students were required to live in the local community during community placements. Community service-learning activities included home visits, delivery of health care to medically under-served families and long-term care facilities, provision of group education in schools and local organizations such as the women’s association, farmers’ association, etc., working with local health workers in community health care and community preventive screening, and the presentation of elective and independent services in the community after thorough planning and discussion with responsible faculty members and community tutors. Students working in the Lu-Ku disaster area also provided follow-up health assessments to the victims of the 1999 earthquake.

Reflection is a learning activity that ties the student community service experiences to academic learning. In this program, we have a reflection session at the end of each week. Tutors and students get together to share feelings and experiences, discuss what has been learned from service-learning, determine if the learning objectives were met, and identify academic meaning for the service-learning work experience. At the end of the course, all students turn in a report reflecting on their learning experiences, feelings, abilities acquired, and the implications their learning experiences towards their future careers.

Aims

This study was designed to answer the following questions: (1) Will student community service-learning attitudes affect their evaluation of the program and it’s effect on their learning? (2) From the students’ viewpoint, which community-service-learning activities were more effective in learning com-munity skills? (3) Does the course design fulfill the learning objectives of our community service-program?

Methods

Questionnaire surveys were used to collect quantitative data for this study. Development of the questionnaires was based on the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE) Survey Instrument (Eyler and Giles,1999). The surveys contain three scales: the Social Attitude Scale (SAS), the Program Characteristic Scale (PCS), and the Ability Scale (AS). The questionnaire items were translated to Chinese and adapted to our culture and objectives of this study. All items from the three scales were answered with a five-point, Likert-type rating scale with the highest point for ‘‘strongly agree’’ and the lowest point for ‘‘strongly disagree’’. Items with an opposite meaning from the majority of the items in the same dimension were scored in an opposite direction with the highest point for ‘‘strongly disagree’’. We calculated the mean score of each dimension by dividing the total score of the dimension with the number of items.

The SAS is designed to evaluate a student’s attitude in serving the student’s own community. It contains 23 items covering six components regarding student attitude on social issues and community service. The ‘‘citizenship’’ component probes for feelings of connectedness with the community, a sense of personal efficacy in affecting community issues, and the belief that the community can solely solve its problems effectively. The ‘‘locus of community problems’’ component measures whether students consider social problems as systemic issues or problems inflicted through individuals’ personal responsi-bility. The ‘‘social justice and political structure’’ component measures how students view social justice, policy, and government agency in affecting the

community. The ‘‘personal value’’ component measures how students value their roles and commitment to serving people. The ‘‘personal gains’’ com-ponent measures what students expect to achieve after the community rota-tion. The ‘‘tolerance’’ component measures students’ ability to work with others in the community. Principle component analysis with varimax rotation of the SAS obtained four factors (social concerns, community responsibility, community orientation, and service attitude) that explained 37.6% of the total variance. An internal reliability study produced a a value of 0.86. All com-munity connectedness items were grouped into factor 1, and all, except for two personal efficacy items, were grouped into factor 2. The community efficacy items were dispersed into two factors.

The PCS contains six components that measure the quality of community placement and the academic linkage to community experiences and learning. These six dimensions are as follows: reflection/discussion, reflection/writing, placement quality, community voice, application, and diversity. Principle component analysis with varimax rotation of the entire scale produced three factors (reflective learning, hands-on experience, and interesting and chal-lenging exposure) that explained 52.2% of the total variance. An internal reliability study produced a a value of 0.91.

The AS measures the learner’s subjective evaluation of skills acquired from the community service-learning program. It contains seven compo-nents: leadership skills, communication skills, teamwork, prospective think-ing, critical thinkthink-ing, identification of social issues, and action skills. Principle component analysis with varimax rotation of the entire scale produced four factors (communication skills, tolerance, leadership skills, and social and ethical considerations) that explained 55.8% of the total variance. An internal reliability test produced a a value of 0.92.

The SAS was completed at the beginning of the course to avoid any change of student attitudes caused by the community service-learning pro-gram. The rest of the questionnaire was completed immediately after fin-ishing the program.

Student reports from the 2002 academic year were reviewed qualitatively to provide more information on the effect of learning in the community program. One reviewer (first author) read all students’ reports and extracted out descriptions related to abilities acquired in community service-learning. These descriptions were reviewed and grouped into different ability dimen-sions according to the learning objectives of the community service-learning program.

Results

Two hundred and forty nine fifth-year medical students finished the com-munity service-learning program and completed the questionnaires during

the 2001 and 2002 academic years. Among them, 126 students (104 male and 22 female) were in the Dou-Liou program, and 123 students (91 male and 32 female) were in the Lu-Ku program. Gender differences were observed in two dimensions of the SAS but not in the PCS or AS, although there was no gender difference throughout the entire SAS score. Female students had lower scores in ‘‘community efficacy’’ (3.28 ± 0.45 vs. 3.48 ± 0.49,p> 0.01) and ‘‘personal value’’ (2.81 ± 0.50 vs. 3.06 ± 0.59, p > 0.01) than male students.

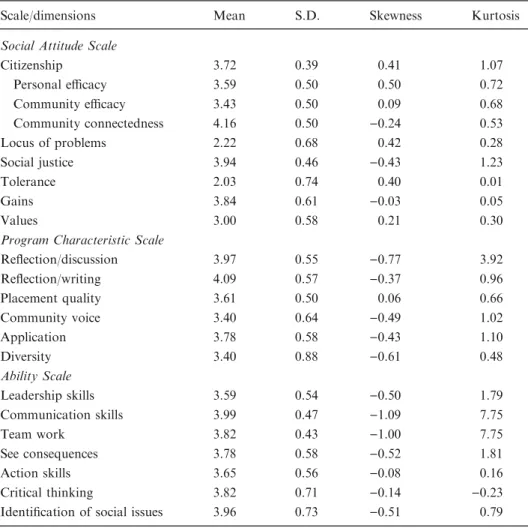

TableI shows the descriptive statistics of the three scales. The results of the SAS indicate that most medical students had a positive attitude towards social service and citizenship but were conservative towards taking up the

TableI. Descriptive statistics of the Social Attitude Scale, Program Characteristic Scale and Ability Scale

Scale/dimensions Mean S.D. Skewness Kurtosis

Social Attitude Scale

Citizenship 3.72 0.39 0.41 1.07 Personal efficacy 3.59 0.50 0.50 0.72 Community efficacy 3.43 0.50 0.09 0.68 Community connectedness 4.16 0.50 )0.24 0.53 Locus of problems 2.22 0.68 0.42 0.28 Social justice 3.94 0.46 )0.43 1.23 Tolerance 2.03 0.74 0.40 0.01 Gains 3.84 0.61 )0.03 0.05 Values 3.00 0.58 0.21 0.30

Program Characteristic Scale

Reflection/discussion 3.97 0.55 )0.77 3.92 Reflection/writing 4.09 0.57 )0.37 0.96 Placement quality 3.61 0.50 0.06 0.66 Community voice 3.40 0.64 )0.49 1.02 Application 3.78 0.58 )0.43 1.10 Diversity 3.40 0.88 )0.61 0.48 Ability Scale Leadership skills 3.59 0.54 )0.50 1.79 Communication skills 3.99 0.47 )1.09 7.75 Team work 3.82 0.43 )1.00 7.75 See consequences 3.78 0.58 )0.52 1.81 Action skills 3.65 0.56 )0.08 0.16 Critical thinking 3.82 0.71 )0.14 )0.23

role and commitment necessary to serve people in the community. The results of the PCS revealed that from the students’ point of view, the quality of the Dou-Liou and Lu-Ku community service-learning courses had reached a more than average level in all dimensions, especially the ‘‘reflection/writing’’ and ‘‘reflection/discussion’’ dimensions, which had mean scores greater than 3.9. The results of the AS revealed that most of the students had achieved what they were supposed to learn from the community service-learning program, especially the ‘‘communication skills’’ and ‘‘ability to identify social issues’’ components.

Student community service attitudes measured by the SAS were weakly correlated to the PCS scores (r = 0.18, p < 0.05) and the AS scores (r = 0.22, p = 0.01) in the bi-variate analysis. Since the PCS and the AS were highly correlated with each other (r = 0.68, p < 0.001), partial correlation was used to avoid confounding factors among these three variables. The relationship between SAS and PCS, and SAS and AS became non-significant after controlling of the third variable, AS or PCS, respectively (rSAS PCS. AS= 0.05, p = 0.27; rSAS AS. PCS= 0.12, p = 0.06). Therefore, the student

community service attitudes did not affect their evaluations or their learning.

TableII presents the correlations between the components in the com-munity service-learning program measured by the PCS and students ability to learn from community service-learning as measured by the AS. Nearly all items in the PCS were highly correlated with items of the AS except ‘‘critical thinking’’. Four components, ‘‘reflection/discussion’’, ‘‘reflection/writing’’, ‘‘placement quality’’ and ‘‘community voice’’ were more effective in learning community skills as perceived by the students. ‘‘Critical thinking’’ was weakly correlated with ‘‘placement quality’’ and ‘‘application’’ only.

TableII. Correlation between program characteristics and acquired abilities Reflection/ discussion Reflection/ writing Placement quality Community voice Application Diversity Leadership skills 0.45*** 0.35*** 0.38*** 0.40*** 0.31*** 0.25*** Communication skills 0.52*** 0.51*** 0.52*** 0.40*** 0.49*** 0.19* Team work 0.55*** 0.51*** 0.49*** 0.42*** 0.47*** 0.32** See consequence 0.41*** 0.38*** 0.40*** 0.28*** 0.48*** 0.28*** Critical thinking 0.18* 0.10 0.29*** 0.13 0.27*** 0.14 Identification of social issues 0.36*** 0.38*** 0.28*** 0.26*** 0.47*** 0.16* Action skills 0.42*** 0.38*** 0.44*** 0.46*** 0.40*** 0.29*** Two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficients.

Quantitative evaluations of student achievements, measured by the AS, showed that most of the students in our program received training in major community medicine management skills (TableI). These results indicate that, with the exception of critical thinking ability, the community service-learning experience accomplished the learning goals of this program. The results of the qualitative analysis of student reports are shown in Table III. In these written reflections, students described their broad learning experiences and the valuable things they learned. Most of the student descriptions were re-lated to how they communicated with people in the community. Students were very appreciative of the opportunity to speak and interact with people from a wide variety of socio-economic backgrounds. They found they were actually participating in community affairs, talking with people in the com-munity, and were able to speak in front of the public. Students also learned a lot from teamwork. They were able to respect other opinions, compromise on different suggestions, make moral and ethical judgments, tolerate different personalities, work with others in the community, and think about others. Students also learned to lead a service group and felt that they were responsible to the community.

Discussion

The purpose of community service-learning in medical education is to cul-tivate community-responsible health professionals. The service-learning experience provided medical students with a greater ability to work within a community setting, identify community health problems, utilize community resources, and cooperate with others in the community. In order to reach these learning objectives, the quality and effectiveness of a community ser-vice-learning program are of the utmost importance.

Our study revealed that most fifth-year medical students have a positive attitude towards community service. However, female students had less aggressive attitudes than male students in serving their community. The gender difference is, perhaps, due to the conservative roles of women in traditional Chinese society. Since there were only a small number of female students in our study, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Student responses to the items of ‘‘locus of community problems’’ indicate that students support societal assistance to the under-privileged instead of leaving communities to solve their own problems. It means that students can understand that such problems are not self-inflicted. They can recognize that society as a whole is also responsible to the suffering of individuals and families.

Our results are in contrast to the findings of previous studies that have demonstrated that medical students are more self-centered and consider their

TableIII. Qualitative analysis of abilities learnt in the community service-learning program Abilities learnt

in the program

Examples in students’ reports

Leadership skills

Feeling responsible for others ‘...Needs to care about the community, the living environ-ment of the patients and the social culture.’

Ability to lead a group ‘...In this activity, I am the leader of the group. I am responsible to contact to local health workers, organize meetings, and coordinate different opinions.’

Communication skills Active participation in community affairs

‘...We are really participated in the community program, teachers gave us advices, classmates discussed together...it is a valuable experience. With the participation of so many community residents, it is something worth to do.’

Good communication with others

‘...Empathy comes from understanding, understanding de-pend on communication, this is what I learned form elderly veterans.’

Able to speak in public ‘‘...I am not good in expression, and feel very nervous to speak in public. I volunteer to took over the speaker’s job as a challenge to myself...I finished the speech smoothly and really felt relax. To me, it is a big accomplishment, better than having a high score in the examination, it is more real, more deep, more touching, and more exciting.’

Team work Respecting different opinions from others

‘...Nevertheless, thought this activity, I interact and discuss with my classmates, learn to respect different opinions and characters, it is my best reward.’

Able to compromise ‘...group members have diverse characters, some speak in loud voice, some remain silence, some insist their opinion, some are in bad temper. I learn how to respect to different characters and successfully avoid tension situations. Capable of making moral

or ethical judgments

‘...We could not forget people who live in the dark side of the society waiting for help. Helping others who needs help is a responsibility of a human being.’

‘...The true value and the essential of a physician are not come from high technology. It depends on the spirit of love that serves people.’

Being tolerant of different people

‘...We work together as a group, use collective wisdom to accomplish our goal and feel like a team.’

Able to work with others ‘...Everyone has his (her) own duty and work together in harmony.’

own interests more than the interests of the public (Eckenfels, 1997). The high mean scores in the ‘‘social justice and political structure’’ dimension indicate that students believe that social changes should be achieved with community effort via political and official channels. However, the low mean score in the ‘‘personal value’’ dimension indicates that students are not confident in performing social services by themselves and are reluctant to volunteer to help people. In general, our students agreed that it is practical and reasonable to solve community problems at the community level. They are willing to work with others to gain personal achievement, but they have limited capability in performing alone at that level.

TableIII. Continued Abilities learnt in the program

Examples in students’ reports

Thinking about others ‘Public health nurses are so competent and very hard work-ing, you can’t imaging how many works she needs to do in a day...I really appreciate for she assistance in our work.’ Ability to see consequences

Able to think about future ‘...Explore my vision, let me look at medicine from a different point of view, for the future, I have another planning and arrangement.’

‘...The most important thing I have learnt is to think about my future career.’

Critical thinking skills

Thinking critically ‘...Do not consider solely from the medical point of view, we should have the ability to search for a solution from another direction.’

Ability to identify social issues Able to identify social issues and concerns

‘...Health problems of elderly who lived alone include phys-ical, psychological and social aspects. It depends on the joint efforts of primary care and social welfare to improve the quality of life of these elderly people.’

‘...In this community, people are simple and honorable, most of the population are elderly and children, and a high per-centage of foreign brides. I think this will be the future issues in primary care.’

Action skills

Able to take action ‘...We organized a health education program about exercise, including the shopping of necessary equipments, contact to suppliers, activity design, and the decoration of the field.’

Dimensions of the PCS questionnaire have been used to evaluate the community service-learning curriculum. The results from the student surveys indicate that the Dou-liou and Lu-Ku community service-learning courses have met all necessary requirements of a community service-learning cur-riculum. Students also gave a high rank to their achievements, indicating that the rotations were fruitful. The reflection/discussion and reflection/writing are two dimensions that received top rankings in the curriculum evaluation. This result is supported by a well-accepted concept that effective reflection is a crucial element for a successful self-learning program (Eyler,2002; Steiner and Sands, 2000). Reflection is also a very important factor in constructive learning; it can help students to apply classroom knowledge to fieldwork to better understand how their achievements in the field can be applied to broader situations. Effective reflection can be achieved in various forms. In our program, an opportunity for discussion reflection was provided by both community tutors in small group discussions at the community service-learning site and by university faculty members through teleconferencing. A written report summarized students’ learning experiences and feelings, serv-ing as written reflection.

The high mean score of all items in the AS questionnaire indicated that students found the service-learning curriculum useful in learning how to take leadership roles in service-learning teams, obtain good communication skills for participating in community affairs, work with people in different posi-tions, and become confident in obtaining good outcomes through community service. These assertions are also demonstrated in their reports.

The lack of correlation between the SAS scores and PCS scores, and the SAS scores and AS scores indicates that although students may have show differences in their social attitudes, they did not change their positive opin-ions regarding the quality of the service-learning program. In other words, students evaluated their curriculum objectively without relying on their preferences.

All characteristics we used to evaluate the program had a significant correlation with the achievement of learning with the exception of abilities in critical thinking. This indicates that critical thinking should be emphasized in the 2-week training session. The learning of critical thinking is related to the quality of reflection/discussion, placement quality, and application skills. This result indicates that students seem to learn more towards critical thinking if they find their learning more interactive and hands-on oriented.

The Lu-Ku community service-learning program was initiated in response to the 1999 earthquake disaster. The program is similar to the program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine that was set up following a devastating flood caused by hurricane Floyd (Steiner and Sands, 2000). However, our program has been extended beyond the acute period of

devastation and continues into the reconstruction stage. Students joining the program at different stages are guided by the same group of faculty and focus their service-learning activities on the same objectives. They are able to see the entire course structure beforehand, as well as the outcomes of the pre-vious groups, utilizing past experiences towards better learning experiences in the future. Unfortunately, program evaluation was implemented 2 years after the beginning of the community service-learning program. Therefore, com-parisons among different stages of the post-disaster community are not possible.

This program provides students with the opportunity to direct their ser-vice-learning through their own community investigation. The learning is dynamic, interactive, and under proper supervision of the faculty members at the learning site and at the medical school. The active student roles enhance their sense of autonomy, responsibility, achievement, and satisfaction. Pas-sive students come from pasPas-sive programs. We do not expect our students to be active learners if there is no room for active participation in the program. In the community service-learning program, students must be active partic-ipants in order to gain more learning from the service experience. Our pro-gram opens up an avenue for students to make contact with people in the community and to apply classroom knowledge to the real world. Although it is very difficult to measure learning outcomes in a quantitative manner, Ec-kenfels (1997) argued that the most valuable things learned from a com-munity service-learning program come from personal experience, such as feelings of self-worth and personal satisfaction, and are not measurable by means of statistical methods. The qualitative analysis of student reports shed light on the understanding of students’ subjective experiences. They value the community program for the training of communication skills, teamwork, leadership skills, and the ability to carry out a community health program. After exposure to the community, some students started to reconsider their career choice for the future. They realized that primary care is of equal importance or even more important than hospital medicine.

While community service-learning has theoretical advantages, the orga-nization and maintenance of such programs demand a great deal of logistic support and faculty involvement. Community support is also a major determinant for the successful implementation of such programs. Commu-nity leaders need to understand the objectives and benefits of commuCommu-nity service-learning for their own community.

In summary, students participating in community service-learning appreciate receiving responsibility and conducting productive work. For the program to succeed, appropriate placement, planned feedback, as well as the opportunity to work with different people as a team, are important factors. By taking this hands-on approach, students can obtain leadership and

communication skills while gaining respect for colleagues, practicing critical thinking, and engaging in community problems at the source with the use of community resources. Such an achievement requires proper supervision and guidance.

Our study has several limitations. It is difficult to draw specific conclusions concerning the outcomes of educational endeavors in such a short period of time. Long-term outcomes are often difficult to obtain, and are not timely indicators of program improvement. In addition, the abilities learned in the community service-learning program were reported by students subjectively. We need an objective assessment to show what students objectively learned from the program. Further research will enable us to design a tool that measures which kinds of service activities can predict a better outcome and what changes in social attitudes are significant after participating in a com-munity service-learning program.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan, ROC (NSC91-2516-S-002-001). The authors wish to thank Yin-Li Tsao for her assistance in this study. We also thank all community tutors and staff members who participated in the community service-learning program.

Appendix

Social Attitude Scale (SAS) Citizenship

Sense of personal efficacy in affecting community issues Most people can have an impact on community problems I can solve the problems of my community

I play an important part in improving my community I do not have time to help others (R)

Belief that the community itself can be effective in solving its problems I think social problems should be solved by efforts from the community Community is capable of solving its own problems

Community should provide social services to its people Feeling connected to the community

Program Characteristic Scale (PCS) Social problems are not my concern (R) I should reach out to serve people Locus of community problems

People who need social services have needs based on personal factors Generally speaking, one’s fortune is determined by one’s self Social justice and political structure

Striving for greater social justice is something I can do to improve society Solving social problems is not government’s responsibility (R)

The most important part of community service is providing service on an individual basis The most important part of community service is in correcting public policy

Tolerance

I feel uncomfortable working with different people Personal gain

I obtain valuable skills and experiences from community service I develop leadership skills through community service

Personal value

I can influence public policy I often volunteer to help people I can present community leadership I am building a career to help people (R): reverse coding

Reflection/discussion

Discussion about the service provided Discussion of learning experiences with faculty Sharing feelings with others

Analyzing community problems

Relating classroom knowledge to community service Reporting service activities

Reflection/writing Daily journal writing

Faculty response to journal entries Writing about projects assigned Placement quality

Imposing important responsibility Participating in challenging tasks Requiring important decision making Appendix.Continued

Ability Scale (AS)

Having interesting assignments Personal participation

Opportunities to talk with people receiving services Being in accordance with professional interests Performing a variety of tasks

Gaining appreciation for the service performed Making actual contributions

Implementation of ideas without restriction Obtaining challenging experiences

Community voice

Recipient involved in service activities planning Projects consider needs of the community Application

Applying classroom knowledge to service projects Applying service achievements to classroom knowledge Diversity

Working with different people

Leadership skills

Feeling responsible for others Knowing where to find information

Knowing whom to contact to get things done Ability to lead a group

Communication skills

Active participation in community affairs Good communication with others

Often discussion on various issues with others Good listening skills

Able to speak in public Team work

Respecting different opinions from others Able to compromise

Capable of making moral or ethical judgments Being tolerant of different people

Being empathetic to all points of view Able to work with others

Thinking about others Appendix.Continued

References

Boelen, C. (1995). Prospects for change in medical education in the twenty-first century. Academic Medicine 70(7 suppl): S21–S28.

Brill, J.R., Ohly, S. & Stearns, M.A. (2002). Training community-responsive physicians. Academic Med-icine 77: 747.

Bruce, T.A. (1996). Medical education in community sites (editorial). Medical Education 30: 81–82. Eckenfels, E.J. (1997). Contemporary medical students’ quest for self-fulfillment through community

service. Academic Medicine 72: 1043–1050.

Eyler, J. & Giles, D.E. (1999). Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Eyler, J. (2002). Reflecting on service: helping nursing students get the most from service-learning. Journal

of Nursing Education 41: 453–456.

Faller, H.S., Dowell, M.A. & Jackson, M.A. (1995). Bridge to the future: nontraditional clinical settings, concepts and issues. Journal of Nursing Education 34: 344–349.

Gupta, T.S. & Spencer, J. (2001). Why not teach where the patients are? Medical Education 35: 714–715. Habbik, B.F. & Leeder, S.R. (1996). Orienting medical education to community need: a review. Medical

Education 30: 163–171.

Honnet, E.P. & Poulsen, S.J. (1989). Wingspread Special Report: Principles of Good Practice for Combining Service and Learning. Racine, WI: Johnson Foundation.

Jacoby, B. (1996). Service-Learning in Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morrison, J. & Watt, G. (2003). New century, new challenges for community based medical education (editorial). Medical Education 37: 2–3.

Petersdorf, R.G. & Turner, K.S. (1995). Medical education in the 1990s – and beyond: a view from the United States. Academic Medicine 70(7 suppl): S41–S47.

Rubenstein, H.L., Franklin, E.D. & Zarro, V.J. (1997). Opportunities and challenges in educating com-munity-responsive physicians. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 13: 104–108.

Seifer, S.D. (1998). Service-learning: community-campus partnerships for health professions education. Academic Medicine 73: 273–277.

Steiner, B. & Sands, R. (2000). Responding to a natural disaster with service learning. Family Medicine 33: 645–649.

Ability to see consequences

Able to foresee consequences of actions Able to think about future

Critical thinking skills Thinking critically

Ability to identify social issues

Able to identify social issues and concerns Action skills

Able to take action

Effective in accomplishing goals Appendix.Continued