Folk concepts of mental disorders among Chinese-Australian patients

and their caregivers

Fei-Hsiu Hsiao

PhD RNAssistant Professor, Department of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan, China

Steven Klimidis

BSc PhD MAPSAssociate Professor, Centre for International Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Harry I. Minas

BMedSc, DPM, MBBS, FRANZCPAssociate Professor/Director, Centre for International Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Eng S. Tan

MBBS, FRCPsych, FRANZCP, DPMAssociate Professor, Centre for International Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Accepted for publication 9 March 2006

Correspondence: Fei-Hsiu Hsiao,

Taipei Medical University, No. 250, Wu-Hsing St., Taipei 110, Taiwan, China. E-mail: hsiaofei@tmu.edu.tw doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03886.x H S I A O F . - H . , K L I M I D I S S . , M I N A S H . I . & T A N E . S . ( 2 0 0 6 )

H S I A O F . - H . , K L I M I D I S S . , M I N A S H . I . & T A N E . S . ( 2 0 0 6 ) Journal of Advanced

Nursing 55(1), 58–67

Folk concepts of mental disorders among Chinese-Australian patients and their caregivers

Aim. This paper reports a study of (a) popular conceptions of mental illness throughout history, (b) how current social and cultural knowledge about mental ill-ness influences Chinese-Australian patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of mental illness and the consequences of this for explaining and labelling patients’ problems. Background. According to traditional Chinese cultural knowledge about health and illness, Chinese people believe that psychotic illness is the only type of mental illness, and that non-psychotic illness is a physical illness. Regarding patients’ problems as not being due to mental illness may result in delaying use of Western mental health services.

Methods. Data collection took place in 2001. Twenty-eight Chinese-Australian patients with mental illness and their caregivers were interviewed at home, drawing on Kleinman’s explanatory model and studies of cultural transmission. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed, and analysed for plots and themes.

Findings. Chinese-Australians combined traditional knowledge with Western med-ical knowledge to develop their own labels for various kinds of mental disorders, including ‘mental illness’, ‘physical illness’, ‘normal problems of living’ and ‘psy-chological problems’. As they learnt more about Western conceptions of psychology and psychiatry, their understanding of some disorders changed. What was previ-ously ascribed to non-mental disorders was often re-labelled as ‘mental illness’ or ‘psychological problems’.

Conclusion. Educational programmes aimed at introducing Chinese immigrants to counselling and other psychiatric services could be made more effective if designers gave greater consideration to Chinese understanding of mental illness.

Keywords: Chinese-Australians, cultural transmission, empirical research report, interviews, mental health, mental illness, nursing

Introduction

New South Wales and Victoria data (Klimidis et al. 1999) have strongly suggested that Chinese-Australians are greatly under-represented in the Western mental health system. Scholars who analysed these data have urged nurses to explore why members of ethnic minority groups, like the Chinese, choose not to access Western mental health services. Social and cultural knowledge about health and illness plays an important role in influencing an individual’s under-standing of illness, and of what constitutes appropriate treatment. In this paper, we report the findings of a research study that examined the impact of Chinese constructions of illness on Chinese patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge about mental illness.

Background

Studies by Kleinman (1977, 1980, 1982), Cheung and Lau (1982), White (1982) and Cheung (1984, 1987) found that in Taiwan, Hong Kong and America, Chinese patients’ and their families’ understanding of the patients’ problems as something other than a mental illness led them to delay using Western mental health services. These studies ascribed this conceptualization of mental illness in Chinese societies to a number of factors including: traditional Chinese medicine concepts of health and illness; the common use of the ‘neurasthenia’ diagnosis among China’s psychiatrists; moral and religious views of mental illness; Western medical views of mental illness, and a psychosocial view of mental illness.

The influence of the historical development of traditional cultural knowledge on care of patients with mental illness has not been explored. Culture is not static but undergoes reconstruction over time, with the result that cultural knowledge is also modified. There have been several accounts of this process. Tomasello (2001) demonstrated that in human culture a process of cultural evolution takes place which, in turn, changes cultural tradition. In the case of health and illness, this means that as scientific knowledge is modified, so what communities learn and assimilate into their cultural tradition can also be modified. Understanding the current cultural beliefs of a group provides a means to understanding how these influence their attitudes to health and illness.

Tomasello (2001) also demonstrated that cultural evolu-tion is a continuous process through the generaevolu-tions, as people acquire cultural knowledge from their families and then modify it. Cultural transmission is mediated by cultural learning, social learning and individual learning (Tomasello

2001). Cultural learning comprises two processes, innova-tion and imitainnova-tion, through which culture undergoes recon-struction and traditional cultural knowledge is modified over time.

A series of studies (Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman 1981, Boyd & Richerson 1985, Schonpflug 2001) indicate that, through social learning, culture is transmitted from one generation to the next through parenting, school, direct teaching, imitation and observation. Individual learning is a variation of social learning.

Social and political factors also influence cultural trans-mission. For example, Tseng and Wu (1985) indicate that the 10-year Cultural Revolution in China suppressed the old Chinese customs and traditional Chinese culture. Cultural transmission was retarded as the younger generation was encouraged to move against traditional culture.

In addition to political factors, traditional culture can face challenges when a foreign culture is introduced into the society. For example, in 1978, a new policy of economic reform began in China, leading China to open itself to Western societies. In addition, media globalization has allowed information about Western concepts of health and illness to be introduced into previously isolated societies, such as China (Kirmayer & Minas 2000).

Emigration similarly exposes people to new social and cultural influences. In the case of Chinese-Australians, it is unclear how acquisition of Western medical knowledge influences their perception of medical care or to what extent their current social and cultural knowledge affects how they explain and label patients’ problems.

Previous studies have indicated that lay people’s explanat-ory models of illness influence how they understand and deal with sickness (Kleinman 1977, 1980, 1982, Cheung & Lau 1982, White 1982, Cheung 1984, 1987). Kleinman (1980) found that popular social and cultural knowledge systems influenced an individual’s understanding of illness and, subsequently, affected that person’s choice of treatment. However, these studies do not examine the issues of social learning and individual learning about mental illness. Con-sequently, there is still little information about the develop-ment of popular conceptions of develop-mental illness over time or the extent to which social and cultural knowledge about mental illness influence help-seeking behaviour.

The study

AimThe aim of the study was to examine (a) popular conceptions of mental illness throughout history and (b) how current

social and cultural knowledge about mental illness influences Chinese-Australian patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of mental illness and consequent explanation of patients’ problems.

Design

A cross-sectional design was used, with home interviews based on Kleinman’s (1980) explanatory model of illness, and previous studies of cultural transmission (Moscovici 1976, 1981, 1988, Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman 1981, Boyd & Richerson 1985, Duveen & Lloyd 1990, Wagner et al. 1999, Kuczynski et al. 1997, Schonpflug 2001, Tomasello 2001).

A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach informed by Ricoeur (1981) was used to analyse patients’ and their caregivers’ concepts of mental illness, seeking to uncover the structure of the narratives and explore their meaning.

Participants

Twenty-eight Chinese-Australian patients diagnosed with a mental disorder and their caregivers volunteered to be interviewed. Twenty-six participants were recruited through four private, Chinese-speaking psychiatrists. The remaining two were recruited through two traditional Chinese medical practitioners in order to obtain data from non-users, as well as users, of Western medical health services. Patients and caregivers were interviewed together, were Mandarin-speak-ers and were all over 18 years of age.

Recruitment

Recruitment via psychiatrists

Standard instructions were given to the psychiatrists, who were asked to give standard information about the study to patients and caregivers. In addition, the psychiatrists gave a brochure to patients and caregivers containing information about the study and inviting them to participate. With the permission of patients and caregivers, the psychiatrists gave their contact numbers to the researcher (F-HH). The resear-cher explained the purpose and nature of the study and invited them to participate. With patients’ and caregivers’ permission, the researcher obtained information about the patients’ diagnoses from the psychiatrists.

Recruitment via Chinese medicine practitioners

Recruitment of participants from Chinese medicine practi-tioners was done using a screening checklist detailing specific symptom criteria to judge whether patients had a mental

disorder. This checklist was developed from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) and the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) (Spitzer et al. 1994, Van Hook et al. 1996) psychosis screening component. If patients met the criteria set out by the checklist (three or more symptoms present), the Chinese medicine practitioner explained the study to them and invited them to participate in a second assessment con-ducted by the researcher to establish the diagnosis. They were asked to give their consent before the interview began. Dur-ing the process of recruitment, one patient stated that he wanted to learn more about his problem, and he subsequently decided to see a psychiatrist, who diagnosed his problem as major depressive disorder. Another patient’s problem had already been diagnosed as schizophrenia by the psychiatrist. These patients were included in this study as they met the recruitment criteria.

Participant demographics

The general characteristics of patients and caregivers were similar. Most patients (26 of 28) and caregivers (24 of 28) were born in China. Most of the immigrant patients (89%) and caregivers (93%) migrated to Australia between 1981 and 1996. The average age was 45 years for caregivers and 46 years for patients. Fifty-three per cent of caregivers and 46% of patients had received higher education. No caregivers were employed in jobs requiring higher education, but one patient was. Thirteen caregivers were the patients’ wife, 10 were their husbands, two were their parents, two were their sisters and one was the patient’s child.

Ethical considerations

Approval for the study was granted by the University of Melbourne Ethics Committee. All participants gave written consent to participate after its purpose, content and possible benefits had been explained to them orally and in writing. They were also informed of the procedures to be adopted to ensure the confidentiality of the data they provided.

Data collection

Data were collected through personal interviews in patients’ homes. Interviews lasted for an average of one-and-a-half hours. They were conducted in Mandarin, tape-recorded, and transcribed by L-HH. Open-ended questions followed by close-ended questions were used to elicit how participants understood the nature of the problem and what labels were used to describe them (Table 1).

Data analysis

In accordance with Ricoeur’s (1981) ideas about how to arrive at a reasonably faithful representation of interviewees’ stories, the following steps were used in the data analysis process.

Uncovering the story structure and identifying the prototypical plot types

The story structure indicates the sequential ordering of events and the relationships that link them to one another. In this study, the typical patient narrative was organized in terms of participants’ first identification of patients’ prob-lems, their application of knowledge about health and illness to interpret patients’ problems, and their understanding of patients’ problems. Under the story structure, three proto-typical plot types identified among the illness narratives demonstrated the main events of the story in this study: social and cultural knowledge about psychotic illness, physical illness and Western non-psychotic illness. These plot types served as cultural resources for participants in attempting to understand patients’ problems. The sequence of events illustrated the process whereby patients and care-givers apply labels to patients’ problems, mediated by social and cultural knowledge. For example, participants began by describing patients’ symptoms in terms of a socially and culturally constructed understanding of psychotic illness. This stage ended when they decided whether the patients’ problem was a psychotic illness. Subsequently, patients and caregivers applied knowledge about physical illness to

explain and label patients’ problems that were not consid-ered to be a psychotic illness. This strategy would continue until patients’ problems could not be explained by know-ledge about physical illness. At this stage, participants explained the patients’ problem by applying acquired knowledge about non-psychotic illness.

Identifying thematic relationships

Examination of Chinese-Australian people’s acquired knowledge about health and illness generated several themes. These provided explanations about traditional cul-tural ideas underpinning beliefs about health and illness, and about the type of changes which might take place when people migrate to a new country and come into contact with new cultural resources. We classified different forms of knowledge, containing different degrees of traditional Chi-nese and Western cultural characteristics, under knowledge about psychotic illness, physical illness and non-psychotic illness. Subsequently, two or three themes were identified under each prototypical plot type. For example, under social and cultural knowledge about psychotic illness the themes included the coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of psychosis, and modified traditional Chinese categories of psychosis. In addition, the themes illustrated patients’ and caregivers’ attitudes towards Western non-psychotic illness. The causal relationships of themes dem-onstrated how patients and caregivers understood different kinds of knowledge and attempted to explain patients’ problems.

Establishing the validity of meanings of narrative interviews In this study, two members of the research team and I were involved in verifying the validity and reliability of the ana-lysis. We reviewed all verbatim transcripts to develop the structure of narratives and to explore their meanings. We then discussed all emerging themes until agreement was reached. I identified themes after examining patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of concepts about illness, including consideration of the how social and cultural context affected the process of forming these concepts. For example, various explanations of ‘depression’ given by participants were identified. Depression was variously described as a normal emotion, an inappropriate social behaviour, or a symptom of illness. The researcher’s subjective understandings and inter-pretations of participants’ stories were involved in the ana-lytic process. With regard to subjective and interpersonal understandings, Kleinman (1994) argued that ‘What the anthropologist seeks to achieve is not objectivity of obser-vation, but controlled interpositionality of interpretation in an academic discourse’ (p. 132).

Table 1 Interview guide

I am going to ask you some questions about your understanding of your problems.

1. When and how did you recognize the problem?

2. How long ago did you first become aware that there were some difficulties or problems?

3. At that time, what did you observe that suggested to you that there was a problem? Probe: For example, did you (the patient) look different, did you do things differently, and did you say things which were unusual? What led you to think that there was a problem?

4. What is the name of your problem?

5. Are there any other names for this problem? If yes, what are they? 6. Do you think that this problem is an illness? If yes, what kind

of illness is it? If no, what kind of problem is it?

7. Did any person help you to understand your problem? If yes, what did these people say to you that helped you understand the problem? Did anything else help you to understand the problem? If no one helped you to understand this problem, where did your understanding come from?

Findings and discussion

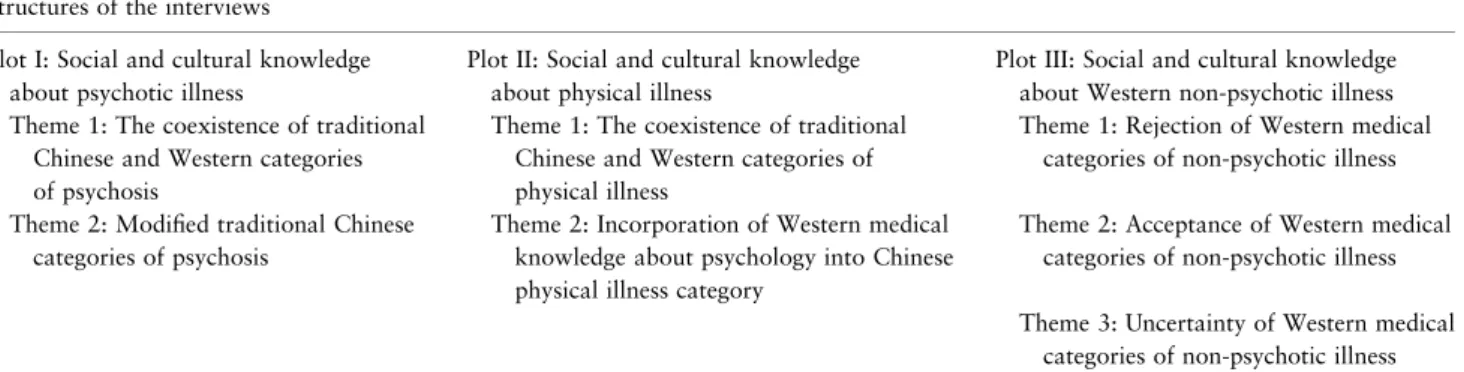

As shown in Table 2, the analysis yielded three prototypical plot types and seven themes. The three prototypical plot types identified were social and cultural knowledge about (a) psychotic illness, (b) physical illness and (c) non-psychotic illness. They were presented as a method of classifying the Chinese popular knowledge system. Among the themes illustrated in the data were (a) what constituted cultural knowledge about psychotic illness, physical illness and non-psychotic illness under each prototypical plot type and (b) how traditional Chinese knowledge was modified, and Western knowledge incorporated, through cultural transmis-sion. The causal relationships of themes demonstrated how patients and caregivers applied cultural information about health and illness to explain patients’ problems as a mental illness, a physical illness, a problem of living, or a psycho-logical problem.

Plot I: Social and cultural knowledge about psychotic illness

We found that social and cultural knowledge about psychotic illness was a prototype of mental illness. Patients’ problems including these symptoms were identified by participants as constituting mental illness. This plot inclu-ded two themes: (i) the coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of psychosis and (ii) modified traditional Chinese categories of psychosis. The historical development of cultural knowledge of Chinese-Australians is well illustrated by this modification of traditional beliefs to incorporate Western knowledge into the popular know-ledge system. Furthermore, it underpins Tomasello’s argu-ment that cultural transmission is mediated by cultural learning, social learning and individual learning (Tomasello 2001).

Theme I: Coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of psychosis

Patients and caregivers had learnt about traditional Chinese medicine’s labels feng (insanity), kuan-tsao (mad-anxious), dian (crazy), dai ping (stupid insanity), shen ching ts’o luan (nerve derangement), and shen ching ping (nerve illness) and Western medicine’s labels, in particular schizophrenia and mental illness. Chinese and Western medical labels shared commonly recognized psychotic symptoms. These symptoms included violent behaviour, disturbed behaviour, disorgan-ized speech, talking to oneself, irritated emotions, inappro-priate affects, and social and occupational dysfunction. One participant described this as follows:

In China, my understanding of mental illness was schizophrenia. The person who suffered from schizophrenia showed bizarre behaviours or thought disturbance…There are a lot of ideas describing this illness. There are a lot of factors contributing to schizophrenia. As I said, the basic factor is imbalance of Yin and Yang. Each patient’s illness is caused by different factors and each person has different physical condition. For example, the patient’s problem may be caused by weak Yin and strong Yang, imbalance of Yin and Yang and so on…

Theme II: Modified traditional Chinese categories of psychosis

The study revealed that concepts from traditional Chinese medicine about psychotic illness had been modified to some extent while maintaining the most important descriptions of symptoms and causal explanations. Feng (insanity) (Yu Tuan 1515) was now classified into two types of illness, wen feng (elegant insanity) and wu feng (violent insanity), based on the distinct symptoms produced by these two illnesses. As one caregiver put it:

In Shanghai, we knew of two types of mental illness. They are ‘Wu feng’ (violent type of insanity) and ‘Wen feng’

Table 2 Plots and themes identified from the interviews Structures of the interviews

Plot I: Social and cultural knowledge about psychotic illness

Plot II: Social and cultural knowledge about physical illness

Plot III: Social and cultural knowledge about Western non-psychotic illness Theme 1: The coexistence of traditional

Chinese and Western categories of psychosis

Theme 1: The coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of physical illness

Theme 1: Rejection of Western medical categories of non-psychotic illness Theme 2: Modified traditional Chinese

categories of psychosis

Theme 2: Incorporation of Western medical knowledge about psychology into Chinese physical illness category

Theme 2: Acceptance of Western medical categories of non-psychotic illness Theme 3: Uncertainty of Western medical

(elegant type of insanity). ‘Wen feng’ refers to the person who talks about something illogically while ‘Wu feng’ refers to the person who attacks people and is aggressive. These people are regarded as mentally ill persons. His (the patient’s) problem (diagnosed as post-traumatic stress dis-order) is not like mental illness. He just has a psychological problem which is caused by his severed fingers…he has the psychological problem which makes his temper bad…it is not an illness…

Plot II: Social and cultural knowledge about physical illness

The study found that Chinese-Australians’ ideas about mental illness were also heavily influenced by their social and cultural knowledge about physical illness. Patients and caregivers associated patients’ physical problems with phys-ical illness. This plot included two themes: (i) the coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of physical illness and (ii) incorporation of Western medical knowledge about psychology into the Chinese physical illness category. Theme I: Coexistence of traditional Chinese and Western categories of physical illness

This theme showed how Western concepts of physical illness could be incorporated into the Chinese popular knowledge system. This may be because Chinese people see the benefits of accepting a different explanation of illness. We found, as did earlier researchers (Yap 1965, Kleinman 1980, Wen & Wang 1980, Lin 1983), that traditional Chinese medicine’s view of shen k’uei (kidney deficiency or weakness charac-terized by physical weakness and caused by sexual problems) and ‘tou feng’ (wind entering in the head, characterized by headache) continued to influence patients’ and caregivers’ interpretations of somatic problems of non-psychotic illness as a physical form of illness:

Caregiver: Before he came here, I talked to him on the phone and I told him why ‘your voice was changed and the voice was different from before’. He told me that he was ill. At that time, he was very ill and he could not talk clearly. In the beginning, we lived here (Australia) and did not know about what was wrong with him in China. We thought that he was weak and he might suffer from ‘shen kuei’ (kidney deficiency or weakness) so he needed to see the doctors. Researcher: Does ‘shen kuei’ mean the men’s sexual dysfunctional problem?

Caregiver: Yes, in China we call this kind of problem ‘shen kuei’. He went to see a Western-style doctor and a Chinese-style doctor to resolve his physical problems.

Theme II: Incorporation of Western medical knowledge about psychology into the Chinese physical illness category This study suggests that the category of neurasthenia was developed by combining information from Western and Chinese medicine. Traditional Chinese medicine’s labels of qi (weakness or spleen weakness) described the symptoms of neurasthenia and attributed this type of illness to the imbal-anced condition of wu hsing (five evolutions phases) (Klein-man 1977, 1982, 1986, 1988, Lee 1994). Western psychology attributed neurasthenia to character problems and the sense of stress. One caregiver accounted for his learning experiences of a psychological view of neurasthenia:

Caregiver: After the 1980s, they (refers to the medical system in China) started to address psychological problems such as how your character problems influence you. They explained your problem from a psychological perspective such as feeling stressed, feeling highly anxious. Having been under high pressure in life for long time caused many problems. I also read this kind of book before.

Researcher: You started to look at your problem from psychological perspective?

Caregiver: Yes, you need to change your character. You need to think about the problem straight and let the thing go. Am I right? When you always think about a trivial thing in detail and make the problem complicated, it will not help you. But you may think that you think in detail. In fact it is not good for you.

Plot III: Social and cultural knowledge about Western non-psychotic illness

We found that foreign culture introduced in the patients’ countries of origin and the experience of migration gave patients and caregivers greater access to information about Western medicine. This study and previous studies (Cavalli-Sforza & Feldman 1981, Boyd & Richerson 1985, Schonp-flug 2001) indicate that through parenting, as well as schooling, culture is transmitted from one generation to next. This plot included three themes indicating three attitudes of patients and caregivers towards non-psychotic illness: (i) rejection, (ii) acceptance and (iii) uncertainty. These three attitudes towards the Western concept of non-psychotic illness were also evident in the work of Kuczynski et al. (1997).

Theme I: Rejecting Western medical categories of non-psychotic illness

Patients and caregivers rejected Western psychiatric diagno-ses because Western psychiatry’s psychophysiological explanation of patients’ physical problems conflicted with

their concept of physical, as well as mental, illness. Their understanding of illness may have been influenced by tradi-tional Chinese medicine’s holistic view of body and mind. As a result, Western dualism, which separates the body and the mind, was unlikely to convince them of the existence of a concept such as psychological illness. As one patient said:

I believed that I had physical problems so I went to see a few general practitioners and another heart specialist. Some of them said that I did not have any problem while some of them gave me medicine in order to resolve my dizziness, my headache, and slow down my heartbeat. They could not resolve my problems. I suffered from side effects. My dizziness was worse and I felt that I would fall down. Therefore, I went to see traditional Chinese medicine doctor. He (traditional Chinese medicine doctor) said that I was anxious and ‘yin huo’ was increased. There was a yang-yin imbalance. He measured my pulse and massaged my head. He (the second traditional Chinese medicine doctor) prescribed Chinese herbal medicine. He told me that ‘yin huo’ increased in my body. My body had too much ‘huo’ which caused my illness.

This is essentially the argument made by Bartlett (1928), who discusses the notion of ‘preferred persistent tendencies’. Bartlett argues that the ideas and values of the new culture are more likely to be accepted if they can be accommodated within an existing belief continuum (preferred persistent tendency), while those that conflict with tradition are more likely to be ignored. In addition to conflicting with the concept of traditional Chinese medicine beliefs, the stigma attached to mental illness also influenced Chinese non-psychotic patients’ preference for expressing distress through physical idioms and rejecting Western explanations of non-psychotic illness (Kleinman 1977, 1980, 1988, Chan & Parker 2004). They often classified the problem as a physical illness and, subsequently, sought medical help from Western physicians and Chinese medicine practitioners.

A number of studies (Furnham & Li 1993, Sue 1994, Ying et al. 2000) examined the impact of acculturation (cultural assimilation) on the experience of emotional distress among Chinese migrants. They found that the factor of old age in migration was positively related to focus on somatic symp-toms, which was a Chinese culturally sanctioned expression of personal and social distress. Based on studying a community sample of Chinese-Americans, Kung (2003) also found that less acculturated participants were more likely to seek physical treatment and less likely to use mental health services for emotional distress than those who were highly accultur-ated. The following quote from a caregiver exemplifies this:

In my life I had never seen anyone who suffers from this illness (anxiety disorder). I did not know about this illness…I have never

suffered from this illness and my family does not suffer from this illness either. So I do not know about this illness. I do not know whether or not this illness is a real illness…She called her friends and they talked about their problems. Now I find out that many people suffer from this illness…Most people who suffer from this illness are women. They are hsin huang (heart restless) or fast heart beat. They said that they had these symptoms and needed to see the doctor. I do not know that if this illness is a contagious illness. This woman said that she had this problem and that woman also said that she had this problem and many of them had this problem. They said that they had this illness but this illness could not be examined. If you have a heart disease, your illness can be examined and you will know that you suffer from a heart illness. But their problems cannot be examined; it depends only on what they say…

Theme II: Accepting Western medical categories of non-psychotic illness

The study found that while some patients and caregivers accepted psychiatrists’ explanations, these did not always explain all their problems, in which case they provided their own labels. For example, the term ‘suspiciousness illness’ described the problem of excessive worry over physical health which is not recognized in Western medicine. In one case, for the patient’s problem diagnosed by the psychiatrist as depression, her husband applied the indigenous label of ‘suspiciousness illness’ to include her problem of excessive worry over physical health. ‘Suspicious illness’ is a common label used by lay people in Chinese society to describe a person who is suspicious and feels insecure about health problem or interpersonal relationships. In this study the pa-tient’s husband provided this label to include the papa-tient’s over-anxiousness about her physical problem that psychiat-rist’s label of ‘depression’ did not include.

We also found that both the Western medical explanation of chemical substances in the brain and Chinese medicine’s explanation of an imbalance of body and mind were accepted to explain anxiety disorder. This finding demonstrated two processes of individual learning, anchoring and objectifica-tion, suggested by several studies (Moscovici 1981, Duveen & Lloyd 1990, Wagner et al. 1999). Anchoring is the process by which people use their pre-existing knowledge to interpret new cultural knowledge. The process of objectification applies when lay people elaborate, interpret and evaluate new knowledge. Through this process, a new form of knowledge emerges, as in the following example:

He (Chinese-style doctor) said that I was anxious and ‘yin huo’ was increased. There was a yang-yin imbalance…He measured my pulse and massaged my head…He (the second Chinese-style doctor) prescribed Chinese herbal medicine…He told me that ‘yin huo’

increased in my body. My body had too much ‘huo’, which caused my illness. I agreed with his explanation. Mental illness is caused by the balance which was disturbed. Psychological problems influence the brain’s function. The body and mind are related…A psycholo-gical problem influences chemical substances in the brain and as a result its influence generates magnetic power which affects the brain’s function.

Theme III: Being uncertain of Western medical categories of non-psychotic illness

Two studies (Cheng 1989, Yeung et al. 2004) found that most Chinese-American patients with depression did not regard depressed mood as a symptom and did not label the problem as a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. In this study, most Chinese-Australian patients and caregivers were not sure whether non-psychotic illness was an abnormal patho-logical disease or a normal problem of living. When patients’ negative emotions emerged from experiencing ‘bad situa-tions’, these emotions were regarded as normal and a part of human life. They used their own life experiences to judge if situations that patients had experienced were ‘bad situations’ and had created stress. Stresses that triggered the patients’ normal emotions included adverse life events, such as a physical injury, the death of a family member, and difficulty in adjusting to migration. For them, these are the problems of

living which people fight in their daily lives, but in a medical world, these same problems are called mental disorders. Their argument resembles those of Szasz (1960, 1995) and Kleinman (1988) on the question of normality and abnor-mality. Szasz (1960) argued that it is common for lay people to fight stress arising from their daily lives, but in a medical world the problems of living are called mental disorders and are regarded as ‘amoral and impersonal’ things (an ‘illness’). In a later paper, Szasz (1995) asserts that medical categories of mental illness disregard the phenomenon of a person struggling in their daily life to have peace of mind, a har-monious relationship or a good life. Similarly, Kleinman (1988) notes that an anthropologist ideally interprets a mental problem as a person’s own experience of demoral-ization and a serious life distress due to social sources, while a psychiatrist regards a mental problem as a psychiatric disease such as depression or neurasthenia.

The data below indicate how such beliefs are manifested. A caregiver describes how the how the emotions of a patient with post traumatic stress disorder can be interpreted and understood in relation to a bad social situation:

Since he got injured, he had experienced many things such as his boss often called him. Sometimes I picked up the phone and his boss’s attitude was very bad. This made me (wife) feel very ‘suppressed’. If you (the researcher) had experienced this for a long time, you would definitely have the problem that he had.

Study limitations

The study has a number of limitations. The lack of represen-tation of younger patients means that the findings do not necessarily apply to younger people, especially as they may have had different educational experiences, which may have exposed them to Western medical knowledge more than older people. Consequently, younger people may be more likely to hold Western views of mental illness than older people. As most participants came from large cities in mainland China, the information about how illness is understood in their society might not be shared by other Chinese people from rural areas or from different countries, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan. Only two interviewees were recruited from a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner. Thus, the data primarily represent the retrospective view of participants who had received Western psychiatric help. Their stories might not be representative of those who may never receive psychiatric such treatment.

The concepts of mental illness derived from the views of two traditional Chinese medicine doctors’ patients and their caregivers are similar to the findings from the other cases

What is already known about this topic

• Traditional Chinese cultural knowledge about mental disorders influences patients and their caregivers in interpreting patients’ problems.

• Caregivers and patients often do not conceptualize the problems as mental illness.

• Consequently, neither patients nor caregivers are inclined to access Western mental health services.

What this paper adds

• Chinese-Australian patients and caregivers combine traditional knowledge with Western medical knowledge to develop their own labels for various kinds of mental disorders.

• Increased knowledge of Western psychology and psy-chiatry leads to changes in understanding of some dis-orders.

• Understanding attitudes of people from different cul-tural backgrounds towards Western concepts of mental illness can enable nurses to help patients gain access to appropriate mental health services.

referred by psychiatrists. For example, traditional Chinese medicine’s view of physical illness continued to influence Chinese people’s interpretations of depressive disorders as a physical form of illness. Nevertheless, some of the psychia-trists’ patients had learnt about non-psychotic illness from the media (television, movies and newspapers), from their life experiences in Australia, and through communicating with psychiatrists. Western knowledge helped them understand what the patients’ problems would be called in Western societies.

Conclusion

Our findings have extended knowledge of the historical development of Chinese popular knowledge systems. They should therefore promote understanding of the ways in which the social and cultural medical knowledge of Chinese migrants may influence their understanding and interpret-ation of mental illness. It is clear that professional healthcare and support institutions should give greater consideration to cultural models of illness in order to improve access to their services. Educational programmes distributed through Chi-nese media and based upon careful consideration of ChiChi-nese understandings of mental illness could encourage more Chinese migrants to use psychiatric and counselling services. Exploring patients’ and caregivers’ cultural beliefs about mental illness also helps to understand how culture shapes their experiences of suffering. Culture influences them to interpret the situation, to make appropriate emotional responses to the situation, and to act in accordance with the local cultural and social context. Healthcare profession-als can learn to be more empathetic with clients from different cultural backgrounds through respecting patients’ and caregivers’ beliefs and values, and understanding how these influence both expressions of distress and coping strategies.

Future studies are needed to (a) examine popular know-ledge systems among a more representative sample of the Chinese-Australian community, (b) extend the study to include migrants to and from other countries and (c) evaluate the ability of educational programmes to improve under-standing of mental illness and the use of mental health services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our particular appreciation to the Chinese-Australian patients and caregivers for generously sharing their stories and for giving the study their warm support.

Author contributions

FHH, SK, HM and EST were responsible for the study conception and design and drafting of the manuscript. FHH, SK, HM and EST performed the data collection and data analysis. SK, HM and EST provided administrative support. FHH, SK, HM and EST made critical revisions to the paper. SK, HM and EST supervised the study.

References

Bartlett F. (1928) Psychology and Primitive Culture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Boyd R. & Richerson P.J. (1985) Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Cavalli-Sforza L.L. & Feldman M. (1981) Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Chan B. & Parker G. (2004) Some recommendations to assess de-pression in Chinese people in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 38, 141–147.

Cheng T.A. (1989) Symptomatology of minor psychiatric morbidity: a cross-cultural comparison. Psychological Medicine 19, 697–708. Cheung F. (1984) Preferences in help seeking among Chinese studies.

Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 8, 371–380.

Cheung F.M. (1987) Conceptualization of psychiatric illness and help-seeking behaviour among Chinese. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 11, 97–106.

Cheung F.M. & Lau B.W.K. (1982) Situational variations of help-seeking behavior among Chinese patients. Comprehensive Psy-chiatry 23, 252–262.

Duveen G. & Lloyd B. (1990) Introduction. In Social Representations and the Development of Knowledge (Duveen G. & Lloyd B., eds), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 1–10.

Furnham A. & Li Y.H. (1993) The psychological adjustment of the Chinese community in Britain: a study of two generations. British Journal of Psychiatry 162, 109–113.

Kirmayer L. & Minas H. (2000) The future of cultural psychiatry: an international perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 45(6), 438–446.

Kleinman A. (1977) Depression, somatization and the new cross-culture psychiatry. Social, Science and Medicine 11, 3–10. Kleinman A. (1980) Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture:

An Exploration of the Bordeland Between Anthropology, Medi-cine, and Psychiatry. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. Kleinman A. (1982) Neurasthenia and depression: a study of soma-tization and culture in China. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 6, 117–190.

Kleinman A. (1986) Social Origins of Distress and Disease: Depression, Neurasthenia and Pain in Modern China. Yale Uni-versity Press, New Haven.

Kleinman A. (1988) Rethinking Psychiatry: From Cultural Category to Personal Experience. The Free Press, New York.

Kleinman A. (1994) An anthropological perspective on objectivity: observation, categorization, and the assessment of suffering. In Health and Social Change in International Perspective (Chen L.C.,

Kleinman A. & Ware N.C., eds), Harvard University Press, USA, pp. 129–138.

Klimidis S., Lewis J., Miletic T., McKenzie S., Stolk Y. & Minas I.H. (1999) Mental Health Service Use by Ethnic Communities in Victoria. Victorian Transcultural Psychiatry Unit, Melbourne. Kuczynski l., Marshall S. & Schell K. (1997) Value socialization in a

bidirectional context. In Parenting and Children’s Internalisation of Values (Kuczynski L. & Grusec J.E., eds), John Wiley, New York, pp. 23–50.

Kung W.W. (2003) Chinese Americans’ help seeking for emotional distress. Social Service Review March, 110–134.

Lee S. (1994) The vicissitudes of neurasthenia in Chinese societies: where will it go from the ICD-10? Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review 31, 153–172.

Lin T.Y. (1983) Psychiatry and Chinese culture. The Western Journal of Medicine 139, 862–867.

Moscovici S. (1976) La Psychanalyse: Son Image Et Son Public. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, France.

Moscovici S. (1981) On social representations. In Social Cognition: Perspectives on Everyday Knowledge (Forgas J.P., ed.), Academic Press, London, pp. 181–209.

Moscovici S. (1988) Notes towards a description of social representations. European Journal of Social Psychology 18, 211– 250.

Ricoeur P. (1981) Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences. Edited and translated by John B. Thompson. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Schonpflug U. (2001) Intergenerational transmission of values: the role of transmission belts. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32(2), 174–185.

Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Kroenke K. & Linzer M. (1994) Utility of a new procedure of diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 272, 1749–1756.

Sue S. (1994) Mental health. In Confronting Critical Health Issues of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (Zane W.S., Takeuchi D.T., Young N.J. & Oaks T., eds), Sage, California, pp. 266–288.

Szasz T.S. (1960) Moral conflict and psychiatry. Yale Review 49, 555–556.

Szasz T.S. (1995) The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist 15, 113–118.

Tomasello M. (2001) Cultural transmission: a view from chimpan-zees and human infants. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 32(2), 135–146.

Tseng W.S. & Wu D.Y.H. (1985) Chinese Culture and Mental Health. Academic Press, Orlando.

Van Hook M.P., Berkman B. & Dunkle R. (1996) Assessment tools for general health care settings: PRIMD-MD, OARS, and SF-36. Health Social Work 21, 230–234.

Wagner W., Duveen G., Themel M. & Verma J. (1999) The mod-ernization of tradition: thinking about madness in Patna, India. Culture and Psychology 5(4), 413–445.

Wen J.K. & Wang C.L. (1980) Shen-k’uei syndrome: a culture-specific sexual neurosis in Taiwan. In Normal and Abnormal Behavior in Chinese Cultures (Kleinman A. & Lin C., eds), D. Reidel Publishing Company, Boston, pp. 357–369.

White G.M. (1982) The role of cultural explanations in ‘somatiza-tion’ and the ‘psychologiza‘somatiza-tion’. Social Science and Medicine 16, 1519–1530.

Yap P.M. (1965) Koro- a culture-bound depersonalization syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry 111, 43–50.

Yeung A., Chang D., Gresham R.L., Nierenberg A.A. & Fava M. (2004) Illness beliefs of depressed Chinese American patients in primary care. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192(4), 324–327.

Ying Y.W., Lee P., Tsai J., Yeh Y.Y. & Huang J. (2000) The conception of depression in Chinese American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 6, 183–195. Yu T. (1515) Xin Feng. InYixue zhengzhuan (Orthodoxy of