Many adolescents experience adjustment prob-lems including externalizing and internalizing problems. Antisocial behavior is an externalizing behavior that refers to persistent violations of behavior patterns that are deemed socially ap-propriate. It is characterized by a broad scope of aggressive and coercive behaviors, including ver-bal and physical aggression, defiance of authority

figures, theft, and truancy. Therefore, it is disruptive to individuals, family and friends, and society. Moreover, antisocial behavior during childhood is predictive of adolescent and adult crime.1–3In a Taiwanese study of 1109 seventh-grade students,4 47.2% reported that they had engaged in deviant behavior in the past year. Research about adoles-cents with antisocial behavior is an important

©2010 Elsevier & Formosan Medical Association . . . .

1Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine, 4Institute of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, and 2Department of Family Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, 3Department of Nutrition and Health Science, School of Healthcare Management, Kanin University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: April 17, 2009 Revised: June 25, 2009 Accepted: July 9, 2009

*Correspondence to: Dr Lee-Lan Yen, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University,

17 Hsu-Chow Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan. E-mail: leelan@ntu.edu.tw

Expressed Emotion and its Relationship to

Adolescent Depression and Antisocial

Behavior in Northern Taiwan

Bee-Horng Lue,1,2Wen-Chi Wu,3Lee-Lan Yen4*

Background/Purpose: Despite widespread recognition of the occurrence of antisocial behavior and

de-pression in adolescents, the specifics of the relationship between them have not been clarified. The pur-pose of this study was to investigate the role of expressed emotion as a proximal factor for depression and antisocial behavior among adolescents, by looking at direct and indirect relationships.

Methods: Secondary data analysis using path analysis was carried out on 2004 data from the Child and

Adolescent Behaviors in Long-term Evaluation project. The study sample consisted of 1599 seventh-grade students in Northern Taiwan. Variables included family factors, personal factors (sex and academic per-formance), expressed emotion [emotional involvement (EI) and perceived criticism (PC)], depression, and antisocial behavior.

Results: We found that one dimension of expressed emotion, PC, directly influenced student depression

and related indirectly to antisocial behavior. Depression was an important mediator between PC and an-tisocial behavior. Another dimension, EI, did not influence either depression or anan-tisocial behavior. Sex was related directly to expressed emotion, depression, and antisocial behavior, and also indirectly to anti-social behavior through PC and depression. Academic performance was related directly to expressed emo-tion and indirectly to antisocial behavior through PC and depression.

Conclusion: Greater PC from parents directly contributed to higher levels of student depression and was

related indirectly to more student antisocial behavior. It is suggested that parents should decrease overly critical parenting styles to promote adolescent mental health and avoid the development of antisocial behavior. [J Formos Med Assoc 2010;109(2):128–137]

means of developing strategies to prevent the problem of adolescent tendency to commit crime, delinquency, or criminal behavior.

Depression is the most prevalent internalizing problem among adolescents.5A United States re-view of depression-related literature in the decade prior to 1996 found that the prevalence of de-pression ranged from 0.5% to 8.3% in adoles-cents, and gave an estimated lifetime prevalence rate of major depressive disorder in adolescents of 15–20%.6 A national survey of physical and mental health in Taiwan conducted in 1999 found that 30.5% of 3487 adolescents aged 12–18 years old had experienced depressive symptoms as their most frequent response to stressful life events.7Early intervention is important as indi-viduals who have depressive symptoms during childhood and adolescence are more likely to have mental problems in young adulthood.6,8

Family factors including family structure, social status, and family relationships are predictors of adolescent antisocial behavior. Enmeshed parent– child relationships and authoritarian parenting styles are the strongest predictors of antisocial behavior.2,9–12 The influence of family structure and socioeconomic status on antisocial behavior is mediated by family relationships.10,11,13 There-fore, family relationships can be an important me-diator in the development of antisocial behavior in adolescents.

Negative parenting practices (e.g. parental re-jection and lack of emotional warmth) are asso-ciated positively with adolescent depression.14–16 A Taiwanese study has found that inept parent-ing, including strict discipline, poor supervision, and non-directive parenting practices, were all associated positively with depressive symptoms and antisocial behavior.17Although aversive fam-ily environments, such as coercive famfam-ily interac-tion, contribute to the development of antisocial and depressive behavior,18–20 perceived positive messages from parents are associated negatively with adolescent depression.21Therefore, the fam-ily’s emotional climate and the quality of parent– adolescent interaction should be the focus of attention for reducing negative outcomes.

Expressed emotion, that is, the affective atti-tudes and behaviors (criticism, hostility, and emotional over-involvement) in family relation-ships is a valuable predictor of the course of psychi-atric disorders such as schizophrenia, depressive and anxiety disorders,22,23 physical illness, and health behavior.24,25 Patients living in an envi-ronment with high expression of emotion have poor illness outcomes and more risk of relapse.22,23 Maternal expressed emotion predicts children’s antisocial behavior,26and perceived hostile criti-cism, mediated through adolescent depression, can explain adolescents’ aggressive behavior, such as irritating others, making others look stupid, backbiting, and tripping.19However, few studies have focused on expressed emotion and antiso-cial behavior. We investigated the relationship between expressed emotion, depression and an-tisocial behavior in adolescents.

Methods

Study framework

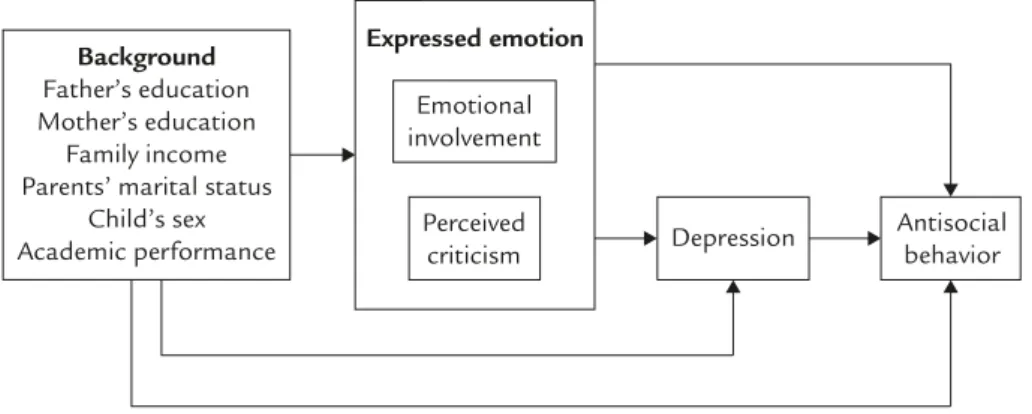

We hypothesized that adolescent antisocial behavior arises directly from depression and ex-pressed emotion, including emotional involve-ment (EI) and perceived criticism (PC) (Figure 1). Depression might also be a mediating factor for the relationship between expressed emotion and antisocial behavior. Family factors including fa-ther’s and mofa-ther’s educational level, parent’s marital status and family monthly income, and personal factors including sex and level of aca-demic performance were assumed to influence antisocial behavior, depression and expressed emotion.

Study sample

Child and Adolescent Behaviors in Long-term Evaluation (CABLE) was a longitudinal study that commenced in 2001.27,28The original sample in-cluded all first-grade students (cohort 1) and all fourth-grade students (cohort 2) in 18 randomly selected public elementary schools in Taipei city and Hsinchu county. Details of the research

design and sampling procedures have been pub-lished previously.27,28

As expressed emotion was only measured in 2004 for cohort 2, a cross-sectional design was used. This sample consisted of 2712 seventh-grade students who completed follow-up. Among them, 1880 students provided their parents’ infor-mation. After removing cases with incomplete data, the final sample size was 1599 students. Comparison of included and excluded students showed no significant differences in antisocial behavior, depression and all background factors, except marital status. The distribution of back-ground variables is shown in Table 1.

Study variables

The operational definitions and measuring scales of key variables are provided in the Appendix and described further below.

Antisocial behavior

Antisocial behavior was defined as behavior that was related to deliberate harm of persons or damage to property,2including attacking others, damage to public property, stealing, or extortion. Students were asked how often they had per-formed such behaviors during the past month, with responses of: (1) never, (2) 1 or 2 days, (3) many days, or (4) every day. Scores for each of these four behaviors were summed to give an overall score. A higher score indicated a greater likelihood of antisocial behavior. The Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.63.

Depression

Depression was measured using the CABLE de-pression scale.17This scale was developed based on Kovacs’ Children’s Depression Inventory29

Background

Father’s education Mother’s education

Family income Parents’ marital status

Child’s sex Academic performance Expressed emotion Emotional involvement Perceived criticism Depression Antisocial behavior

Figure 1. Study framework: factors related to adolescent antisocial behavior.

Table 1. Distribution of personal and family factors among 1599 seventh-grade students in Northern Taiwan, 2004* Personal factors Sex Male 781 (48.84) Female 818 (51.16) Academic performance

Ranked in the top 10 544 (34.02)

Rank order position 11–20 624 (39.02) Rank order position> 20 431 (26.95)

Family factors

Father’s education

Junior high school and under 217 (13.57) Senior/vocational high school 922 (57.66)

College and above 460 (28.77)

Mother’s education

Junior high school and under 222 (13.88) Senior/vocational high school 1068 (66.79)

College and above 309 (19.32)

Parents’ marital status

Married and living together 1300 (81.30)

Other situations 299 (18.70)

Family income (NT$/mo)

≤ 39,999 218 (13.63)

40,000–79,999 615 (38.46)

80,000–119,999 408 (25.52)

≥ 120,000 358 (22.39)

and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children of Faulstich et al.30 Students rated seven items about emotions and vegetative symptoms in the previous 2 weeks with: (1) never; (2) once or twice; or (3) many times. The total score ranged from 7 to 21. A higher score indicated a greater severity of de-pressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.78.

Expressed emotion

Expressed emotion was measured using the Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS) of Shield et al.31,32FEICS was used to measure family relationship and to assess perceived family criticism and emotional over-involvement from the perspective of the respon-dent. It comprised two sub-concepts: EI and PC; EI referred to the level of perceived emotional over-involvement of family members, and PC to the level of perceived critical comments from family members. Fourteen items were scored on a five-point Likert scale of 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Total subscale scores ranged from 7 to 35. Higher scores represented higher levels of EI or PC. The reported Cronbach’s α for EI and PC for 13–18-year-old Irish adolescents was 0.64 and 0.75, respectively.33The Cronbach’s α for the scale in this study was 0.77 and 0.59, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using SAS statistical software (Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics of variable distribution were followed by path analysis using LISREL 8.05 to test the study hypothesis and investigate direct and indirect relationships between variables. As the study variables included nominal and ordinal vari-ables, criteria for multivariate normality were not fulfilled. Therefore, we first had to calculate the asymptotic covariance matrix and used the weighted least-squares parameter estimates to estimate the direct and indirect relationships in the model.34 The model’s goodness of fit was assessed by the following indices: χ2/degrees of freedom (DF) < 5; root-mean-square error of ap-proximation (RMSEA) <0.05; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) close to 1.

Results

Distribution of expressed emotion, depression, and antisocial behavior

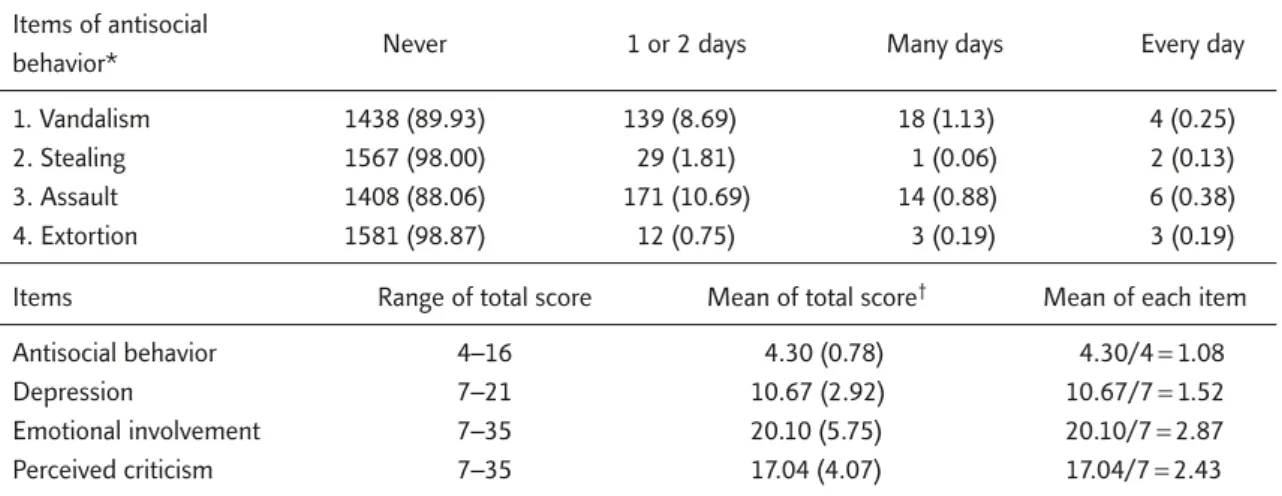

As shown in Table 2, attacking others was the most frequent antisocial behavior (11.94%), fol-lowed by vandalism (10.07%). Stealing (2%) and extortion (1.13%) were less common. The mean score per item of antisocial behavior was

Table 2. Distribution of antisocial behavior and mean scores of antisocial behavior, depression, emotional involvement, and perceived criticism among 1599 seventh-grade students in Northern Taiwan, 2004

Items of antisocial

Never 1 or 2 days Many days Every day

behavior*

1. Vandalism 1438 (89.93) 139 (8.69) 18 (1.13) 4 (0.25)

2. Stealing 1567 (98.00) 29 (1.81) 1 (0.06) 2 (0.13)

3. Assault 1408 (88.06) 171 (10.69) 14 (0.88) 6 (0.38)

4. Extortion 1581 (98.87) 12 (0.75) 3 (0.19) 3 (0.19)

Items Range of total score Mean of total score† Mean of each item

Antisocial behavior 4–16 4.30 (0.78) 4.30/4= 1.08

Depression 7–21 10.67 (2.92) 10.67/7= 1.52

Emotional involvement 7–35 20.10 (5.75) 20.10/7= 2.87

Perceived criticism 7–35 17.04 (4.07) 17.04/7= 2.43

1.08. This fell between never and 1 or 2 days, which indicated that antisocial behavior was not severe in our sample. The mean score per item for depression was 1.52. This fell between never and once or twice, which indicated that our sam-ple did not have a severe level of depression. The mean scores per item for expressed emotion were 2.87 for EI and 2.43 for PC. These fall between occasionally and sometimes. Therefore, the study sample had a moderate level of expressed emotion. Relationships among antisocial behavior, depression, and expressed emotion

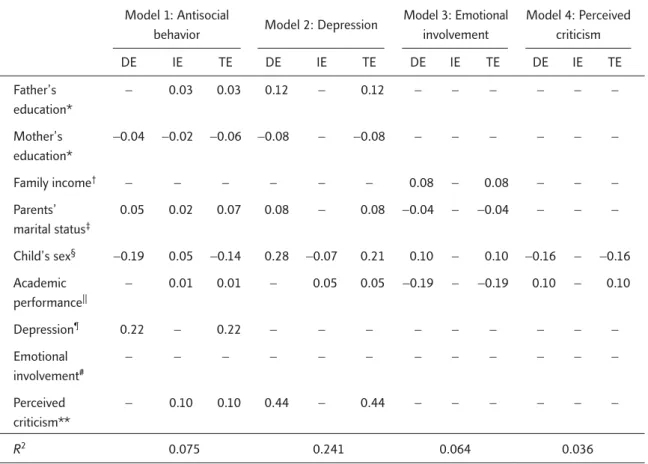

Direct and indirect relationships among vari-ables were established using path analysis (Table 3 and Figure 2). The coefficient of each path was standardized and only those variables that achieved

statistical significance (p< 0.05) were kept in the model. All goodness-of-fit indices indicated an acceptable fit between the model and data: χ2/ DF (0.23), RMSEA (0.0), GFI (1.00), and AGFI (0.99).

According to model 1, mother’s education, parental marital status, sex, and depression had direct effects on students’ antisocial behavior, with depression having the greatest impact (standard coefficient= 0.22). Parental education, parental marital status, sex, academic performance and PC had indirect influences on antisocial behavior. Model 1 confirmed that depression mediated the relationship between PC and antisocial behavior. PC was correlated positively with depression. Model 1 explained 7.5% of the variance in antiso-cial behavior.

Table 3. Results of path analysis: standardized direct and indirect effects of antisocial behavior, depression, emotional involvement and perceived criticism among 1599 seventh-grade students in Northern Taiwan, 2004

Model 1: Antisocial

Model 2: Depression Model 3: Emotional Model 4: Perceived

behavior involvement criticism

DE IE TE DE IE TE DE IE TE DE IE TE Father’s − 0.03 0.03 0.12 − 0.12 − − − − − − education* Mother’s −0.04 −0.02 −0.06 −0.08 − −0.08 − − − − − − education* Family income† − − − − − − 0.08 − 0.08 − − − Parents’ 0.05 0.02 0.07 0.08 − 0.08 −0.04 − −0.04 − − − marital status‡ Child’s sex§ −0.19 0.05 −0.14 0.28 −0.07 0.21 0.10 − 0.10 −0.16 − −0.16 Academic − 0.01 0.01 − 0.05 0.05 −0.19 − −0.19 0.10 − 0.10 performance|| Depression¶ 0.22 − 0.22 − − − − − − − − − Emotional − − − − − − − − − − − − involvement# Perceived − 0.10 0.10 0.44 − 0.44 − − − − − − criticism** R2 0.075 0.241 0.064 0.036

*1= Junior high school and under, 2 = senior/vocational high school, 3 = college and above; †(NT$/month): 1= < 40,000, 2 = 40,000– 79,999, 3= 80,000–119,999, 4 = ≥ 120,000; ‡1= married and living together, 2 = other situations; §1= male, 2 = female; ||1= class rank position 1–10, 2= class rank position 11–20, 3 = class rank position > 20; ¶higher score means a greater degree of depression; #higher score means a higher level of emotional involvement; **higher score means a higher level of perceived criticism. DE= direct effect; IE= indirect effect; TE = total effect (DE + IE).

Model 2 demonstrated that parental educa-tion level, parental marital status, sex and PC had a direct impact on students’ depression, with PC being the most important predictor (standard coefficient= 0.45). Sex and academic perfor-mance were correlated indirectly with depression, through PC. This means that boys and students with poor academic performance tended to have higher PC, which resulted in more depression. Model 2 accounted for 24% of the variance in depression.

Model 3 demonstrated that students who were female and had higher family income, stable par-ent’s marital status, and higher academic perfor-mance were more likely to experience EI. This model explained 6.4% of the total variance.

Model 4 demonstrated that students who were male and had poorer academic performance were more likely to receive criticism. Model 4 explained 3.6% of the total variance. However, there was no

significant relationship between EI and depres-sion, or between EI and antisocial behavior.

Discussion

Based on the results of path analysis, we found no direct relationship between expressed emotion and antisocial behavior. However, PC can influ-ence the expression of antisocial behavior indi-rectly through depression. Students who are male or have poor academic performance reported higher levels of PC.

Relationships between antisocial behavior, depression, and expressed emotion

We found that sex and level of depression were associated directly with expression of antisocial behavior, whereas PC was related indirectly to anti-social behavior through depression. This mediating

Figure 2. Path analytic model: standardized solutions of emotional involvement, perceived criticism, depression and

antisocial behavior among 1599 seventh-grade students in Northern Taiwan, 2004. χ2= 6.30, degrees of freedom = 27, p = 0.99 Depression Emotional involvement Perceived criticism Child’s sex Mother’s education Parents’ marital status Father’s education Family income Academic performance 0.12 0.08 0.10 0.10 −0.08 0.08 0.28 0.22 −0.04 −0.04 0.05 0.62 0.60 0.75 −0.19 −0.16 Antisocial behavior 0.44 −0.19

effect of depression agrees with the findings of Hale et al,19 however, we did not find a direct effect of PC on female adolescent behavior. Hale et al have measured antisocial behavior as physi-cal and verbal aggression. In our study, it was re-served for more serious acts such as vandalism and deliberate theft.

Several studies have found that prevalence rates of adolescent depression are higher in females, and that males perform more aggressive behav-iors than females.16,18,20,35We had similar findings for the direct effect of sex on adolescent depression and antisocial behavior. It is possible that females are more sensitive to negative interpersonal interactions than males, which leads to increased depression.36,37 For the indirect effect of sex on antisocial behavior, one possible route was through depression, and another was through PC and depression.

In Chinese society, traditional values view boys as more important for the family’s future (e.g. they are responsible for taking care of the household and carrying on the family name), which often results in parents being stricter with sons.38 When raising girls, parents adopt the attitude of “San-Tsung-Si-De”.38,39This refers to traditional Chinese views about raising female children. Girls are meant to be raised to be obe-dient to their fathers at home, their husbands when married, and their sons when their hus-band dies. The four fundamentals for educating girls in traditional culture are behavior, speech, appearance, and needlework and cooking. We found that girls were more able to feel EI and boys tended to feel PC. Therefore, boys are more vulnerable to criticism in the context of Chinese culture and traditional parenting patterns. Relationship between expressed emotion and depression

We found no significant relationship between EI and depression. The EI items in FEICS31were de-veloped originally to reflect a negative and en-meshed type of family involvement. However, the components of EI might include a desirable element of family belongingness that would

be correlated negatively with depression.32,33,40 Furthermore, some research has indicated that EI can be either a risk factor or a protective factor according to family situation and outcome vari-ables.31,41The reason for not finding a direct re-lationship between EI and depression in our study might be the close parent–child ties that are emphasized strongly in families in Taiwan.38We suggest further study to clarify the relationship.

As in previous studies,16,19,20,22,23,31–33,40 we found that there was a strong positive relation-ship between PC and depression. As a result of parental opposition, criticism, changing ex-pectations, or punishment, including corporal punishment, which is acceptable in Taiwan, chil-dren might develop a negative view of the self-world, which results in selective attention to negative events, avoidance, social withdrawal, and even depression.18,42

An old Chinese proverb from the Sung Dynasty, “Studying is the noblest of human pursuits”, demonstrates how the importance of academic excellence has deep roots in Chinese society. Chil-dren’s high academic performance indicates their parent’s success in child raising, and removes the need to worry about the child’s future success.38,43 Chinese parents use restrictive and controlling parenting styles,38,43similar to the authoritarian parenting style in Baumrind’s parenting style typologies, in which parents are typically strict, expect obedience, and assert power when their children misbehave.44

Studies of the association between children’s academic performance and authoritarian parent-ing style have shown inconsistent results in families from diverse ethnic backgrounds, even within Asian societies.45,46 Under strict parental discipline, children are more likely to perceive critical comments from their parents. Our study found a negative relationship between academic performance and EI, and a positive relationship between academic performance and PC. It has been proposed that academic performance plays an important role in the parent–child relation-ship. Poor academic performance might cause adolescents to perceive criticism from their parents.

This in turn would influence adolescent’s de-pression and lead to the exde-pression of antisocial behavior.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to our study. As ex-pressed emotion was only measured in the 2004 CABLE survey, we were only able to conduct a cross-sectional analysis, and hence a causal rela-tionship between depression and antisocial behav-ior could not be established. The alpha coefficient for the measure of PC was only modest. However, the robust association between PC and depression indicated that it does measure a valid construct.

In conclusion, this study was concerned with investigating the impact of expressed emotion on adolescent depression and antisocial be-havior. We found that the most important factor that influenced adolescent antisocial behavior was PC from family relationships. PC also acted through depression to have a significant indirect effect on antisocial behavior. When investigating adolescent antisocial behavior, depression is an important issue to consider. In addition, parent– child relationships should be improved to pre-vent adolescent depression. As a result of the importance of PC, when children’s academic performance is not ideal, parents should encour-age their children as opposed to punishing or criticizing them. This is particularly the case for males, because under Chinese traditional values, male adolescents are put under greater pressure by parents than are female adolescents. Parents’ beliefs and values regarding their children’s aca-demic performance is an important topic for future research.

Acknowledgments

This study analyzed some of the 2004 data from the Child and Adolescent Behaviors in Long-term Evolution (CABLE) project, which was funded by the National Health Research Institutes, Republic of China (grant HP-090-SG03). The authors would like to thank the students, parents, interviewers,

supervisors and school administrators for their assistance with data collection.

References

1. Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, eds. Developmental Psychopathology,

Vol 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, 2ndedition. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2006:503–41.

2. Loeber R. Development and risk factors of juvenile antiso-cial behavior and delinquency. Clin Psychol Rev 1990; 10:1–41.

3. Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, et al. Developmental tra-jectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: a six-site, cross-national study. Dev Psychol 2003;39:222–45.

4. Kao MY, Wu CI, Lue BH. The relationships between inept parenting and adolescent depression dimension and con-duct behaviors. Chinese J Fam Med 1998;8:11–21. 5. Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, et al. Adolescent

psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depres-sion and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school stu-dents. J Abnorm Psychol 1993;102:133–44.

6. Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35: 1427–39.

7. Department of Statistics, Ministry of Interior, Taiwan. The National Survey of Physical and Mental Health of Youth in Taiwan, 1999.

8. Aronen ET, Soininen M. Childhood depressive symptoms predict psychiatric problems in young adults. Can J

Psychiatry 2000;45:465–70.

9. Dekovi M, Janssens JMAM, Van As NMC. Family predic-tors of antisocial behavior in adolescence. Fam Process 2003;42:223–35.

10. Hou C. Family structure, family relationships, and delin-quency. Res Appl Psychol 2001;11:25–43. [In Chinese] 11. Wells L, Rankin JH. Families and delinquency: a

meta-analysis of the impact of broken homes. Social Problems 1991;38:71–93.

12. Rosen L. Family and delinquency: structure or function.

Criminology 1985;23:553–73.

13. Smith CA, Stern SB. Delinquency and antisocial behavior: a review of family processes and intervention research.

Soc Serv Rev 1997;71:382–420.

14. Gerlsma C, Emmelkamp PM, Arrindell WA. Anxiety, depression, and perception of early parenting: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 1990;10:251–77.

15. Rapee RM. Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clin Psychol Rev 1997;17:47–67.

16. Muris P, Schmidt H, Lambrichs R, et al. Protective and vulnerability factors of depression in normal adolescents.

Behav Res Ther 2001;39:555–65.

17. Wu WC, Kao CH, Yen LL, et al. Comparison of children’s self-reports of depressive symptoms among different family interaction types in northern Taiwan. BMC Public

Health 2007;7:116.

18. Compton K, Snyder J, Schrepferman L, et al. The contri-bution of parents and siblings to antisocial and depressive behavior in adolescents: a double jeopardy coercion model. Dev Psychopathol 2003;15:163–82.

19. Hale WW III, Van Der Valk I, Engels R, et al. Does per-ceived parental rejection make adolescents sad and mad? The association of perceived parental rejection with ado-lescent depression and aggression. J Adolesc Health 2005; 36:466–74.

20. Steinhausen HC, Metzke CW. Risk, compensatory, vulner-ability, and protective factors influencing mental health in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 2001;30:259–80.

21. Liu YL. Parent-child interaction and children’s depression: the relationships between parent-child interaction and children’s depressive symptoms in Taiwan. J Adolesc 2003; 26:447–57.

22. Butzlaff RL, Hooley JM. Expressed emotion and psychi-atric relapse: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:547–52.

23. Kavanagh DJ. Recent developments in expressed emotion and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1992;160:601–20. 24. Fiscella K, Campbell TL. Association of perceived family

crit-icism with health behaviors. J Fam Pract 1999;48:128–34. 25. Fiscella K, Franks P, Shields CG. Perceived family criticism and primary care utilization: psychosocial and biomedical pathways. Fam Process 1997;36:25–41.

26. Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Morgan J, et al. Maternal expressed emotion predicts children’s antisocial behavior problems: using monozygotic-twin differences to identify environ-mental effects on behavioral development. Dev Psychol 2004;40:149–61.

27. Yen LL, Chen L, Lee SH, et al. Child and adolescent behav-iour in long-term evolution (CABLE): a school-based health lifestyle study. Promot Educ 2002;(Suppl 1):33–40. 28. Yen LL, Chiu CJ, Wu WC, et al. Aggregation of health

behaviors among fourth graders in northern Taiwan.

J Adolesc Health 2006;39:435–42.

29. Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatr 1981;46:305–15. 30. Faulstich ME, Carey MP, Ruggiero L, et al. Assessment of

depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). Am J Psychiatry 1986;143:1024–7.

31. Shields CG, Franks P, Harp JJ, et al. Development of the Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS): a self-report scale to measure expressed emo-tion. J Marital Fam Ther 1992;18:395–407.

32. Shields CG, Franks P, Harp JJ, et al. Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS): II. Reliability and validity studies. Fam Syst Med 1994;12:361–77. 33. Nelis SM, Rae G, Liddell C. Factor analyses and score

va-lidity of the Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale in an adolescent sample. Educ Psychol Meas 2006; 66:676–86.

34. Jöreskog K, Sörbom D. PRELIS 2: User’s Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International, 1996. 35. Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annu

Rev Psychol 2001;52:83–110.

36. Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differ-ences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol Bull 2001;127:773–96. 37. Hetherington JA, Stoppard JM. The theme of disconnection in adolescent girls’ understanding of depression. J Adolesc 2002;25:619–29.

38. Lin WY, Wang JW. The Chinese’s parenting belief.

Indige-nous Psychol Res Chinese Soc 1995;3:2–92. [In Chinese]

39. Lam CM. A cultural perspective on the study of Chinese adolescent development. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 1997; 14:95–113.

40. Lue BH, Leung KK, Fan-Jiang CS, et al. A study of social support, family interaction in relation to mental health.

Chin J Fam Med 1995;15:173–82.

41. King S, Dixon MJ. The influence of expressed emotion, family dynamics, and symptom type on the social adjust-ment of schizophrenic young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:1098–104.

42. Stark KD, Humphrey LL, Crook K, et al. Perceived family environments of depressed and anxious children: child’s and maternal figure’s perspectives. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1990;18:527–47.

43. Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev 1994;65: 1111–9.

44. Spera C. A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achieve-ment. Educ Psychol Rev 2005;17:125–46.

45. Chao RK. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev 2001;72:1832–43.

46. Garg R, Levin E, Urajnik D, et al. Parenting style and acade-mic achievement for East Indian and Canadian adolescents.

Appendix. Measurement of antisocial behavior, depression, emotional involvement, and perceived criticism

Item Scale

Antisocial behavior

In the past month, have you deliberately damaged public property 1= never (e.g. drawn on or engraved walls, desks or chairs, or broken glass)? 2= 1 or 2 days

In the past month, have you stolen things from others? 3= many days

In the past month, have you used weapons or other objects to attack others? 4= every day In the past month, have you extorted from others?

Depression

In the past 2 weeks, have you not felt like eating even your favorite foods? 1= never In the past 2 weeks, have you felt sad or in a bad mood? 2= once or twice In the past 2 weeks, have you felt like crying for no reason? 3= many times In the past 2 weeks, did you find it difficult to carry out tasks?

In the past 2 weeks, have you felt very frightened? In the past 2 weeks, have you had trouble sleeping?

In the past 2 weeks, have you lacked motivation to do things? Emotional involvement

I am upset if anyone else in my family is upset. 1= almost never

My family knows what I am feeling most of the time. 2= occasionally

Family members give me money when I need it. 3= sometimes

My family knows what I am thinking before I tell them. 4= often

I often know what my family members are thinking before they tell me. 5= always If I am upset, people in my family get upset too.

If I have no way of getting somewhere, my family will take me. Perceived criticism

My family approves of almost everything I do. (Reverse the direction 1= almost never

of this score when calculating the total score) 2= occasionally

My family finds fault with my friends. 3= sometimes

My family complains about the way I handle money. 4= often

My family approves of my friends. (Reverse the direction of this score 5= always when calculating the total score)

My family complains about what I do for fun. My family is always trying to force me to change.