On: 24 April 2014, At: 18:09 Publisher: Taylor & Francis

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of

Human-Computer Interaction

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hihc20

Impact of Ergonomic and Social

Psychological Perspective: A Case Study

of Fashion Technology Adoption in

Taiwan

Chyan Yang a & Yi-Chun Hsu a a

National Chiao Tung University , Taiwan, R.O.C. Published online: 17 May 2011.

To cite this article: Chyan Yang & Yi-Chun Hsu (2011) Impact of Ergonomic and Social Psychological Perspective: A Case Study of Fashion Technology Adoption in Taiwan, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 27:7, 583-605, DOI: 10.1080/10447318.2011.555300

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2011.555300

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

ISSN: 1044-7318 print / 1532-7590 online DOI: 10.1080/10447318.2011.555300

Impact of Ergonomic and Social Psychological

Perspective: A Case Study of Fashion Technology

Adoption in Taiwan

Chyan Yang and Yi-Chun Hsu

National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan, R.O.C.Recently, there have been dramatic and emerging innovations in portable media devices. This is evident, for example, with the Apple iPod, Microsoft Zune, Sony Walkman, and the Samsung and iriver media players. Because of this, how to best understand the users’ intentions to adopt these fashionable technologies has become a new issue in the information technology domain. However, in the literature, little is published about what motivates people to adopt these innovative technologies. To address this issue, this research sought to come up with a model by integrating key variables from the role of ergonomic and social psychological facets on estimates of the fashion technology acceptance. A structural equation modeling approach was used to examine 10 hypotheses in the proposed model. The results indicated that usefulness, playfulness, and aesthetics from the ergonomic facet and critical mass from the social psychological perspective positively contributed to the users’ intent to adopt the fashion technology. Furthermore, the perceived ease of use indirectly affects adoptive intentions through perceived usefulness and playfulness. Important impli-cations of these findings are discussed from both theoretical and practical aspects.

1. INTRODUCTION

Today, the hedonic-oriented information technologies influence many aspects of our lives, which extend to communication, social activities, entertainment, and more. Over the past two decades, a significant part of the literature has been dedi-cated to examining and understanding factors that impact users to accept or reject a particular information technology usage (Carayon-Sainfort, 1992; Davis, 1989; Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989; W. Hong, Thing, Wong, & Tam, 2002; Horton, Buck, Waterson, & Clegg, 2001; Igbaria, Parasuraman, & Baroudi, 1996; Moon & Kim, 2001). However, few of the studies were done specifically to address the acceptance of hedonic-oriented technologies. Fashionable, or fashion, technology, such as digital audio players and mobile music phones, can be viewed as a special

Correspondence should be addressed to Chyan Yang, Institute of Information Management, National Chiao Tung University, No. 1001, University Road, Hsinchu City 300, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: nsc.professor.yang@gmail.com

type of hedonic-oriented information technology, and they have been invented at a dramatically fast pace. There are usually three major elements—pleasure, art, and innovation—and they are different from the use of software packages and utilitar-ian technologies, which were the general topics studied in the previous research. Users who adopt these portable media devices hope that such technologies will allow them to obtain and listen to music anytime and anywhere and thus improve the convenience of sharing and carrying music. Users no longer have to take mul-tiple CDs with their CD players, because they can just carry a small and stylish portable digital device containing all of their music. On the other hand, individ-uals who possess these fashion technologies can also display their individuality and unique personality (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001). According to a report con-ducted by Jupiter Research (Cohen, 2006), in the United States, the base for digital music devices will expand from 37 million users in 2006 to 100 million users in 2011. This indicates that the popularity of such technologies will continue to grow in the future. Because of the increasing demand for emerging fashionable tech-nologies in the everyday lives of individuals, these techtech-nologies bring many large business opportunities to the consumer electronics industry. An increasing num-ber of companies such as Apple, Microsoft, Sony, and Samsung are making sub-stantial investments in this area. It is worthwhile to elucidate what factors make an individual adopt or ignore a fashion technology and provide some leverage suggestions to those organizations that design hedonic information technologies.

Apple, one of major players in the fashion technology industry, manufactures the iPod, which is now the world’s most popular and fashionable portable media device on the market. It was initially launched in October 2001. Different models of iPods are also being invented by Apple. These are popularly known as the iPod Shuffle, Nano, Classic, and Touch. Up until now, the Apple iPod and its varia-tions have proven to be a milestone in fashion technology. As of September 2008, the iPod has an incredible history of selling more than 160 million units across the globe and capturing 73.4% of the market share for portable MP3 players in the United States (Apple, 2008). It also holds a first-place position in Taiwan’s MP3 market (J. J. Lee, 2007). Therefore, we can say that the iPod has revolutionized the world of portable media devices. Based on its simplicity and stylish design, the iPod has become a hot device in current society. Individuals can use an iPod to conveniently listen to music, watch movies, view photos, play games, and even store documents. Currently, the name “iPod” is almost synonymous with the term “portable media device” (Weisbein, 2008). Due to the success of the iPod and its dominance in the market, we have some questions. Why do people choose the Apple iPod? Is it attributable to the visual design, fun accessories, or just because everyone has one and people want to fit in? In addition, what are the critical fac-tors that determine the adoption of such fashion technology? How do these facfac-tors affect users’ intentions? Do the adopters and potential adopters have the same per-ceptions toward such innovative technology? In the past, user acceptance toward this type of technology was paid little attention. For this reason, there is a need to develop a proper model to solve these curious research questions.

This article differs from previous studies because it is one of the first studies to investigate the reasons behind users’ adoption of fashionable technology. The focal technology is the Apple iPod. In view of the preceding research questions, this current study came up with a model by integrating key variables from the

Intention to Adopt Fashion Technology

(IAFT)

Perceived Critical Mass (PCM) Social Norms (SN)

Social and Psychological Factors

H1 H3

H4

H5 Perceived Usefulness (PU)

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

H2 Perceived Playfulness (PP)

Perceived Aesthetics (PA) H6 H7 H9 H10 H8 Ergonomics Factors

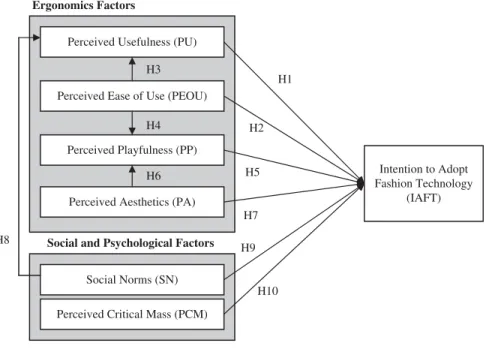

FIGURE 1 Research model.

role of ergonomic and social psychological facets on estimates of the fashion tech-nology acceptance. Accordingly, based on related literature, we have treated the perceived usefulness, ease of use, playfulness, and aesthetics as ergonomic factors. We have also treated social norms and perceived critical mass as social psycholog-ical factors. After that, we tested the model empirpsycholog-ically using online survey data obtained from a cross-sectional study conducted in Taiwan.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES

Figure 1 illustrates the overview of the proposed research model, which asserts that the intention to adopt fashion technology (IAFT) is determined by four ergonomic factors: perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), per-ceived playfulness (PP), and perper-ceived aesthetics (PA). There are also two social psychological factors: social norms (SN) and perceived critical mass (PCM). The construct relationships and hypotheses are elaborated as follows.

2.1. Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use

Since its introduction by Davis (1989) and Davis et al. (1989), the technology accep-tance model (TAM), adapted from Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) theory of reasoned action (TRA), has widespread acceptance as a general and powerful model for understanding information systems/information technology (IS/IT) acceptance. According to TAM, user adoption and usage behavior are determined by the

intention to use IS/IT. There is a direct and positive effect between attitude, intention to use, and actual usage. The TAM also identifies ease of use and use-fulness as key predictors that influence the users’ acceptance of new technologies. Davis (1989) defined PU as the degree to which a person believes that using the new technology will enhance or improve his or her work performance and defined PEOU as the degree to which a person believes that using the new technology would be free of effort. Both PU and PEOU constructs determine the attitude toward using (AT), and PEOU also has a positive effect on PU. Furthermore, PU and AT are expected to directly influence behavioral intention to use (BI).

Researchers have previously validated the TAM in many different contexts. For example, TAM has been successfully used to explain the acceptance of intranet use (Horton et al., 2001), specific software packages (Chau, 2001), data warehous-ing software (Wixom & Todd, 2005), the World Wide Web (Moon & Kim, 2001), IT satisfaction (D. Lee, Rhee, & Dunham, 2009), e-services systems (Lin, Shih, & Sher, 2007; López-Nicolás, Molina-Castillo, & Bouwman, 2008), a hedonic infor-mation website (Van der Heijden, 2004), and e-learning systems using a sample of employees taken from six international companies in Taiwan (Ong & Lai, 2006). W. Hong et al. (2002) proposed an extended TAM model in the context of dig-ital libraries services and found that PU and PEOU both had significant effects on BI. Also, consistent with TAM, PEOU was a causal antecedent to PU. Another research study conducted by Nisbet (2006) used the TAM model to predict the customer’s intention of using gambling technologies and suggested that PEOU and PU are two significant constructs of an intention to use the system. Venkatesh (2000) presented an anchoring and adjustment-based TAM model to learn how that perception forms and changes and revealed that PEOU and PU play a critical role in influencing the BI of the system over time. Based on this literature review, it is expected that usefulness and ease of use from TAM are also applicable to the fashion technology context. When an individual perceives that a fashion technol-ogy is useful and easy to use, he or she may have a positive intention to adopt that technology. We defined PEOU as the degree to which a person who uses the fashion technology was free from effort. PU was defined as the degree to which a person believed that using fashion technology would fulfill his or her expectations. In addition, IAFT was the extent to which the user would like to adopt fashion technology in the future. Therefore, the following hypotheses are offered:

H1: Perceived usefulness will positively influence the users’ intentions to adopt fashion technology.

H2: Perceived ease of use will positively influence the users’ intentions to adopt fashion technology.

H3: Perceived ease of use will positively influence perceived usefulness.

2.2. Perceived Playfulness

Many previous studies have been aimed at finding the effect of additional fac-tors that could interpret behavior toward using a specific technology. Playfulness (similar to “enjoyment” or “fun”), which is mentioned in Lieberman’s pioneering

works (Lieberman, 1977) and Barnett’s studies (Barnett, 1990), can be considered to be either a state of mind (Moon & Kim, 2001) or an individual trait (Webster & Martocchio, 1992). Moon and Kim (2001) defined playfulness as consisting of three dimensions: concentration, curiosity, and enjoyment. They also found that PP had a significant effect on the intention to use the Internet. In Martocchio and Webster’s (1992) study, they posited that individuals considered to be high on the playfulness trait demonstrated higher performance and showed higher responses to micro-computer training. Previous studies have also revealed the importance of the role of playfulness on acceptance of IT (Agarwal & Karahanna, 2000; Dickinger, Arami, & Meyer, 2008; Fang, Chan, Brzezunski, & Xu, 2006; Hsu & Lin, 2008; Igbaria et al., 1996; J. J. Lee et al., 2007; Lin, Wu, & Tsai, 2005; Liu & Arnett, 2000; Shin, 2009; Van der Heijden, 2004; Venkatesh, 2000). Atkinson and Kydd (1997) tested the influ-ence of individual characteristics of playfulness and motivation on the use of the World Wide Web. They suggested that playfulness is significantly related to use, especially for entertainment purposes. Van der Heijden (2004) linked PEOU to perceived enjoyment, and he found that perceived enjoyment and PEOU are all strong determinants of the intention to use a hedonic technology. Furthermore, PEOU also had a positive effect on perceived enjoyment. Similarly, Shin (2009) determined the factors influencing the adoption of IP-based technologies and demonstrated that PP is positively related to the intention to use. Based on these findings, there is a need for us to examine the playfulness construct in our research model. We believed that the acceptance of fashion technology comes not only from an extrinsic motivation, such as usefulness and ease of use, but also from hedonic or intrinsic motivation (playfulness). If users are more playful with the fashion technology, they will be more willing to use them. Thus, this study defined PP as the degree to which a person believed that enjoyment could be derived when using the fashion technology. We therefore hypothesize the following:

H4: Perceived ease of use will positively influence perceived playfulness. H5: Perceived playfulness will positively influence users’ intentions to adopt

fashion technology.

2.3. Perceived Aesthetics

Unlike simple IS/IT adoption, the acceptance of fashion technology includes not only IT adoption but also the pleasurable consumption behavior. A significant body of prior research on human–computer interaction has begun to consider the role of aesthetics in the context of web page design (Cyr, Bonanni, Bowes, & Ilsever, 2005; Lavie & Tractinsky, 2004; Park, Choi, & Kim, 2004; Schenkman & Jonsson, 2000; Tractinsky, Cokhavi, Kirschenbaum, & Sharfi, 2006), Internet por-tals (Van der Heijden, 2003), online shopping (Shang, Chen, & Shen, 2005), and mobile services (Cyr, Head, & Ivanov, 2006; Ha, Yoon, & Choi, 2007). Van der Heijden (2003) investigated an extended TAM model adding a new construct called “perceived attractiveness,” which was defined as “the degree to which a person believes that a website is aesthetically pleasing to the eye.” Results found that visual attractiveness of a website affected the user’s enjoyment as well as the

perceptions for ease of use. Other research conducted by Schenkman and Jonsson (2000) suggested that beauty was the primary predictor for preferring a website. In Cyr et al.’s (2006) work, they proposed that an augmented TAM model introducing a hedonic factor named the “design aesthetic” and found that visual design aes-thetics did significantly impact usefulness, ease of use, and enjoyment. All of these factors eventually influenced the user’s loyalty toward a mobile service. The path from design aesthetics to enjoyment is more significant than the path from aes-thetics to usefulness and ease of use. Ha et al. (2007) demonstrated that perceived attractiveness positively affects perceived enjoyment and the attitude toward play-ing mobile games. Finally, some empirical evidence also found that aesthetics was correlated with user satisfaction with websites (Lindgaard & Dudek, 2003).

In another point, aesthetics was found to play a prominent role in new technol-ogy (product) acceptance and marketing strategies. According to Jordan (1998), aesthetics embraced three notions (Karvonen, 2000): “simplicity,” “design qual-ity,” and “pleasantness.” When there is a strong determinant of pleasure during the interaction, this can increase the desirability of the product. Past studies in the field of product management have also found that aesthetically pleasing prop-erties have a significant influence on users’ preference of an industrial product (Yamamoto & Lambert, 1994). This is because aesthetic impressions have influ-ence on both users’ memories and their decision processes when they consider purchasing products (Kim, 1998). In addition, Hassenzahl (2004) further separated product characteristics into two categories: pragmatic (similar to extrinsic values) and hedonic attributes (similar to intrinsic values). Pragmatic attributes are related to the person’s need to achieve behavioral purposes derived from the use experi-ence. Meanwhile, hedonic attributes are associated with the person’s self-derived impression from the product’s appearance. The Apple iPod is heralded as an “aes-thetic revolution” and is different from general utilitarian technology. It can be recognized as pragmatic because it provides effective and efficient ways for the user to fulfill his or her goals. Furthermore, it could also be perceived as hedo-nic because it provides personal identification by its novel or trendy features. We believe that people often follow some general principles of “styles” or “trends” because they want to be considered fashionable and show their individuality. Based on these discussions, aesthetics is a good predictor of a fashion technol-ogy’s overall impression. Thus in this study we defined perceived aesthetics as the degree to which a person believed that the fashion technology is attractive and pleasurable to the eye. The hypotheses are as follows:

H6: Perceived aesthetics will positively influence perceived playfulness. H7: Perceived aesthetics will positively influence the users’ intentions to adopt

fashion technology.

2.4. Social Norms

SN (also called “subjective norms” or “social influences”) are considered in improving the understanding of an individual’s adoption behavior. Many classic

theories in psychology such as the TRA (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and the the-ory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991) provided the theoretical basis for a relationship between SN and an individual’s behavior. Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) identified the factors of attitude and subjective norms as two important determi-nants of behavioral intention and defined subjective norms (SN) as an individual’s perception that it is important that others think he or she should or should not perform the behavior. Furthermore, Ajzen (1991) also hypothesized that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control can accurately predict an indi-vidual’s behavioral intentions. In the TAM2 model, a revision of TAM, Venkatesh and Davis (2000) confirmed that SN have a significant impact on PU and the direct intention to use. A number of empirical studies incorporated this construct into their research models and found some positive support (Bock, Zmud, & Kim, 2005; Herrero Crespo & Rodriguez del Bosque, 2008; S. J. Hong & Tam, 2006; Hsu & Lu, 2007; Jeyaraj, Rottman, & Lacity, 2006; K. C. Lee, Kang, & Kim, 2007; Lucas & Spitler, 1999; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003; Yi, Jackson, Park, & Probst, 2006). Bock et al. (2005) employed the augmented TRA model to understand knowledge-sharing behavior in an organization, and they found that the greater the subjective norms to share knowledge are, the greater the intention to share knowledge will be. Yi et al. (2006) integrated the key findings of the three paradigms including TAM, TPB, and Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT) and tested their model in the context of personal digital assistant (PDA) acceptance by healthcare professionals. They finally posited that SN had a strong positive effect on PU and BI to use PDAs directly. Otherwise, SN have also been shown to have a positive effect on both PU and the intention to use web-based IS (K. C. Lee et al., 2007). They explained that individuals may use a web-based system because their supervisors or peers think that they should use it. In another vein, SN from the influence of reference groups (e.g., peers, superiors, and relatives) have been verified as a prominent influence on consumer behavior (Bearden & Etzel, 1982; Childers & Rao, 1992). Based on the literature just reviewed, we believe that the effect of SN should not be ignored in the context of fashion technology. When a person perceives that important influencers recommend that a particular technol-ogy is useful, this person will incorporate the influencer’s suggestion into his or her own mental system for future reference. Then he or she may have a positive perception of the usefulness and intention toward further adopting the technology. Thus, according to the definition by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), we defined SN as the degree to which a person believes that important others would expect him or her to use fashion technology. The following hypotheses are presented:

H8: Social norms will positively influence perceived usefulness.

H9: Social norms will positively influence users’ intentions to adopt fashion technology.

2.5. Perceived Critical Mass

The IDT proposed by Rogers (1983) is a robust and well-known theoretical background used to realize the process by which an innovation (technology) is

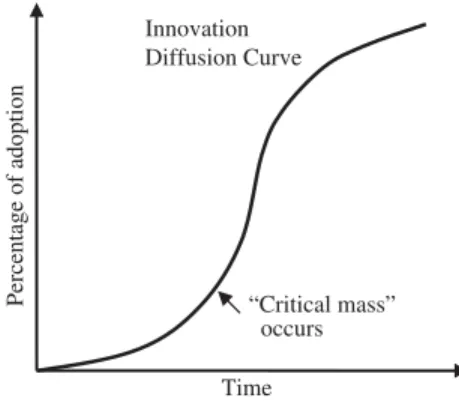

introduced to members of a social system over time. IDT defines “diffusion” as a process where an innovation spreads through certain channels over time among the members of a social system (Rogers, 1995). Rogers pointed out that innovation would disseminate through a social system in an S-shaped curve (see Figure 2). In the initial diffusion stage, innovators and early adopters first selected the inno-vation. They further developed their own perceptions about an innovation and also suggested other impressions that they already use that innovation. Once the diffusion of an innovation reaches the threshold of “critical mass,” the percentage of adoption increased almost exponentially until it reached its saturation point in the last diffusion stage. This is critical, or else innovation is in danger of falling into disuse. Hence, the occurrence of critical mass is important to the sustainabil-ity of innovation. Rogers described critical mass as “the certain minimal number of innovation adopters for the further rate of adoption to become self-sustaining” (Rogers, 1995, p. 318). When more and more people adopted the innovation, it was perceived as increasing benefits to both adopters and potential adopters. This is also similar to the concept of positive network externalities (Katz & Shapiro, 1985, 1986). It refers to the case when an adopter will benefit more from an innovation as the total number of adopters for this innovation increases.

There is a rich body of theoretical and empirical literature regarding the role of PCM in the context of diffusion of different innovations (technologies; Mahler & Rogers, 1999; Strader, Ramaswami, & Houle, 2007). Lou, Luo, and Strong (2000) proposed an extended TAM model that incorporates PCM as an independent vari-able for predicting groupware acceptance. They found that PCM had the largest total effect on an intention to use groupware both directly and on indirect impact. Hsu and Lu (2004) also used TAM that combines social influence (including PCM and SN) and flow experience to demonstrate users’ acceptance of online games. Although they found that the PCM did not have a direct significant impact on intention, it still had an important indirect effect on intention through attitude. In Song and Wladen’s (2007) study, they posited that perceived network externali-ties are positively associated with the intention to adopt peer-to-peer technologies.

Time

Percentage of adoption “Critical mass” occurs Innovation Diffusion Curve

FIGURE 2 Innovation diffusion S-shaped curve. Note. Based on Rogers (1995).

Furthermore, Van Slyke et al. (2007) used the TRA model and the innovation diffu-sion theory by developing a research model to test adoption of the communication technology. The results indicate the importance of PCM in understanding BI (both direct and indirect effects) regarding instant message use. Similarly, their findings were also confirmed by recent work; Premkumar, Ramamurthy, and Liu (2008) showed that PCM had the most significant influence on the intention to use instant messaging. Because of the discussions just mentioned, we expect perceptions of critical mass of fashion technology to positively influence the intention to adopt that innovation. When an individual believes that an innovation has a critical mass of users, it is possible that the individual is willing to use the innovation because of its greater quality, abundance of postpurchase services, and complementary gad-gets (beneficial to both adopters and potential adopters) related to the innovation (Katz & Shapiro, 1985). Therefore, we state the following hypothesis:

H10: Perceived critical mass will positively influence the users’ intentions to adopt fashion technology.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1. Measurement Development

In this study, the research model contains seven constructs, and each composed three items. All items were adapted from previously published studies and mod-ified to make them suitable to the context of fashion technology. The PU, PEOU, and IAFT constructs were measured using the items extracted from Davis (1989), Davis et al. (1989), and Davis and Venkatesh (1996). PP was measured by adapting the scale of Agarwal and Karahanna (2000) and of Moon and Kim (2001). Scale items for PA were derived from Van der Heijden (2003) and Cyr et al. (2006). Furthermore, to develop a scale for measuring social diffusion factors such as SN and PCM, we used items from Hsu and Lu (2004), Lou et al. (2000), and Lucas and Spitler (1999). The questionnaire also contained some demographic ques-tions. A list of the items and descriptive statistics for all constructs are provided in Appendix A. Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

To validate the instrument, we first performed a pretest and pilot test before conducting the main survey. The purpose of the pretest was to ensure that the items were adapted appropriately to the current situation. In the pretest process, we asked five respondents who were experts in the field of fashion technology to give us some comments on the length and sequence of items, questionnaire format, and wording of the scales. Finally, a pilot test was undertaken with 49 self-selected respondents in order to reduce possible ambiguity. Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis were used in this stage. After that, we further modified some unclear instruments from the respondents’ feedback and the results of the pilot test. Based on the pretest and the pilot test, we believe that the final items of our survey were reliable and valid.

3.2. Data Collection and Participants

The data used to test the research model were obtained from an online survey conducted in Taiwan. We adopted an online-based survey because it has several advantages over traditional paper-based surveys, including geographically unre-stricted samples, lower costs, and faster responses (Pettit, 2002). The analysis unit of this study is the individuals who know the Apple iPod. The survey lasted for 3 weeks. In that period, we placed survey messages on some popular online, iPod-related message boards such as the well-known PTT BBS (telnet://ptt.cc) in Taiwan, the fashion guide website (http://www.fashionguide.com.tw/), the EYNY discussion board (http://www.eyny.com/), and more. To increase the response rate, we offered an incentive to respondents who filled out the question-naire completely: an opportunity to participate in a lucky draw for several prizes. Moreover, we checked the IP and e-mail addresses to eliminate repeat responses. The online survey yielded 504 participants for analysis, and 491 of them were complete and valid. There were no cases of missing data in the sample, because respondents could not submit their responses online unless the information was completely filled out.

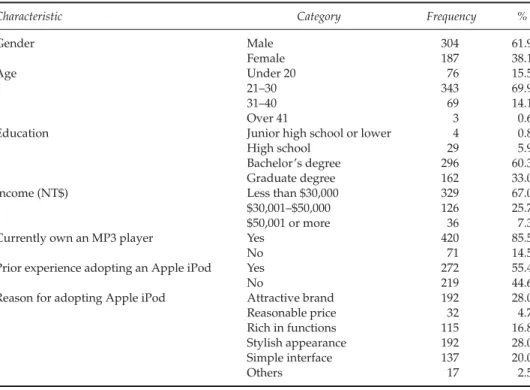

Table 1 describes the demographic profile of the 491 usable participants. Slightly more male (304 respondents) than female (197 respondents) individuals com-pleted the survey, and the male-to-female ratio was approximately 6:4. Most

Table 1: Demographic Profile

Characteristic Category Frequency %

Gender Male 304 61.9 Female 187 38.1 Age Under 20 76 15.5 21–30 343 69.9 31–40 69 14.1 Over 41 3 0.6

Education Junior high school or lower 4 0.8

High school 29 5.9

Bachelor’s degree 296 60.3

Graduate degree 162 33.0

Income (NT$) Less than $30,000 329 67.0

$30,001–$50,000 126 25.7

$50,001 or more 36 7.3

Currently own an MP3 player Yes 420 85.5

No 71 14.5

Prior experience adopting an Apple iPod Yes 272 55.4

No 219 44.6

Reason for adopting Apple iPod Attractive brand 192 28.0

Reasonable price 32 4.7 Rich in functions 115 16.8 Stylish appearance 192 28.0 Simple interface 137 20.0 Others 17 2.5 Note. N= 491.

subjects were between 21 and 30 years of age (69.9%), and more than half of respondents had a bachelor’s degree (60.3%), indicating that the subjects of this research were primarily young and educated. This distribution coincided with a recent report conducted by iSURVEY.com, one of the professional consumer mar-ket research websites in Taiwan, which found young users (younger than 30 years old) dominate the majority of the consumers in the market of Apple iPod. Also, more than three fourths of participants (85.5%) owned an MP3 player at that time. Around 55.4% of respondents (adopters) had the experience of adopting the Apple iPod, whereas 44.6% of the subjects (nonadopters) had no experience in using it. Attractive brand (28%) and stylish appearance (28%) were the most common reasons for choosing the Apple iPod.

4. RESULTS

The test of our collected data was carried out using the structural equation mod-eling method, which is a two-stage approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The measurement model is estimated using confirmatory factor analysis to test the reliability and validity of the proposed model. After an accept-able measurement model had been achieved, the structural model was used to perform the direction and significance of causal relationships between various latent variables. In our study, AMOS 7.0 with maximum likelihood estimation was employed to test the measurement and structural model.

4.1. The Measurement Model

The aim of the measurement model was evaluated on the criteria of reliabil-ity, convergent validreliabil-ity, discriminant validreliabil-ity, and model-fit analysis. The initial confirmatory factor analysis results indicated that item SN1 from the social norms scale should be dropped for further analysis, as SN1’s item reliability (0.274) had a lower than 0.5 cutoff value (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998; Kline, 2005). As shown in Table 2, after removing SN1 from the instrument, 20 items were retained, and item reliability ranged from 0.519 to 0.880. Reliability of the constructs was estimated by composite reliability. Consistent with the recommen-dations of Hair et al. (1998) and Fornell and Larcker (1981), the lowest value of composite reliability (SN= 0.722) in our study was above the benchmark of 0.7, indicating the evidence of adequate reliability.

The validity analysis of the measurement model was assessed by convergent and discriminant validity (Hatcher, 1994). Convergent validity is demonstrated when different items are used to measure a single latent variable, and scores from these different items are strongly correlated. Discriminant validity, on the other hand, indicates that a given latent variable is different from other latent variables. We tested convergent validity by using two criteria (Fornell & Larcker, 1981): (a) all item factor loadings should be significant and greater than 0.7, and (b) average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent variable should exceed 0.5. As evident in Table 2, all item factor loadings and AVE values exceeded the threshold, with

Table 2: Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Item Factor Loading Item Reliability Cronbach’sα Composite Reliability Average Variance Extracted

PU1 0.788 0.622 0.828 0.8319 0.6233 PU2 0.841 0.707 PU3 0.736 0.541 PEOU1 0.852 0.726 0.857 0.8713 0.6948 PEOU2 0.911 0.830 PEOU3 0.727 0.528 PP1 0.802 0.643 0.891 0.8981 0.7468 PP2 0.938 0.880 PP3 0.847 0.717 PA1 0.919 0.845 0.931 0.932 0.8203 PA2 0.894 0.799 PA3 0.904 0.818 SN2 0.782 0.611 0.720 0.7223 0.5657 SN3 0.721 0.519 PCM1 0.823 0.678 0.823 0.8297 0.6193 PCM2 0.747 0.558 PCM3 0.789 0.623 IAFT1 0.930 0.865 0.921 0.9255 0.8056 IAFT2 0.906 0.820 IAFT3 0.855 0.731

Note. PU= perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use; PP = perceived playfulness;

PA= perceived aesthetics; SN = social norms; PCM = perceived critical mass; IAFT = intention to adopt fashion technology.

factor loading ranging from 0.721 to 0.930 and the AVE varying from 0.566 to 0.820. Therefore, our model meets the convergent validity criteria. To further check discriminant validity, we applied the criteria suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981): The square root of the AVE of each latent variable should be higher than the correlations of the construct with other constructs. As can be seen in Table 3, this criterion is satisfied, as the square roots of the AVE values (on the diagonal) all exceeded the interconstruct correlation. In addition, the correlations between all pairs of constructs are below the recommended value of 0.8 (Kline, 2005). These provide evidence that our research constructs are distinct and have strong discriminant validity.

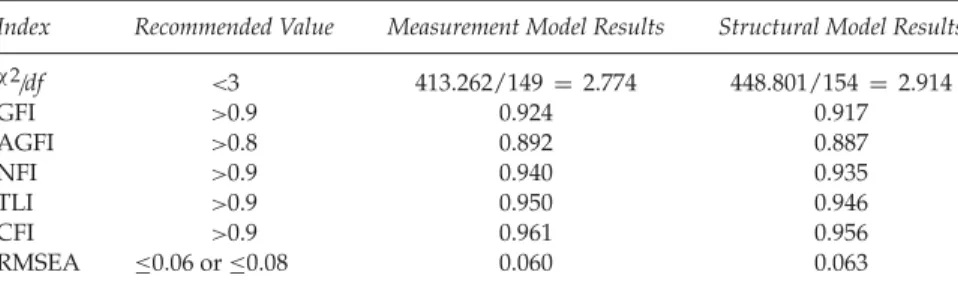

Finally, model fit analysis was done to determine that the measurement model exhibited a fairly good fit with the collected data. To assess the model fit, we applied the following seven common indices: the chi-square/degrees of freedom (χ2/df ), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). In our study, the ratio of chi-square to the degrees of freedom was included instead of the chi-square test, because the chi-square statistic is sensitive to a large sample size. Based on the minimum criteria mentioned in the previous literature (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Scott, 1995; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), all the model-fit indices of the measurement model succeeded to meet their respective common acceptance levels (χ2/df = 2.774,

GFI= 0.924, AGFI = 0.892, NFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.950, CFI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.060).

Table 3: Discriminant Validity PU PEOU PP PA SN PCM IAFT PU 0.789 PEOU 0.753 0.834 PP 0.664 0.654 0.864 PA 0.506 0.426 0.635 0.906 SN 0.385 0.363 0.370 0.409 0.752 PCM 0.286 0.325 0.213 0.256 0.444 0.787 IAFT 0.541 0.487 0.607 0.507 0.341 0.325 0.898 Note. Diagonal elements (in italics) are the square root of the average variance extracted.

PU= perceived usefulness; PEOU = perceived ease of use; PP = perceived playfulness; PA = perceived aesthetics; SN= social norms; PCM = perceived critical mass; IAFT = intention to adopt fashion tech-nology.

In summary, the result of the model-fit analysis also demonstrated adequate evidence of unidimentionality of the items.

4.2. The Structural Model

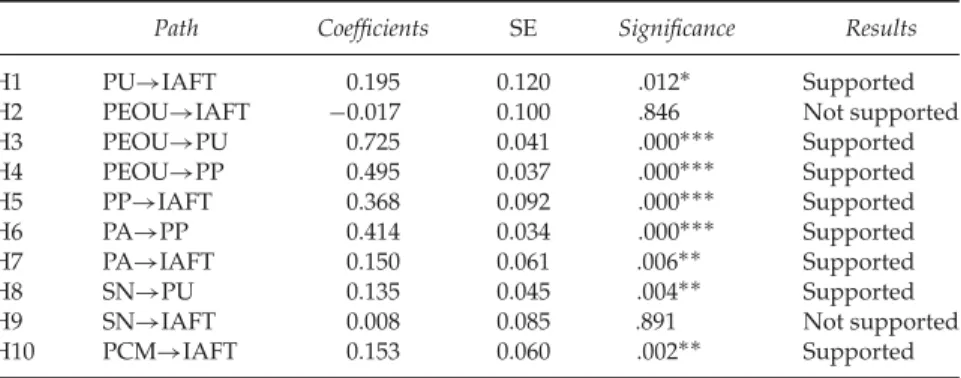

The test of the structural model focused on the estimates of path coefficients; R2 values; and direct, indirect, and total effects on the intention. Before we exam-ine the hypotheses relationships among the latent variables, a similar set of GFI indexes was used to test the structural model. As shown in Appendix B, all fit indices met the desired level, demonstrating that the structural model also had adequate model fit. After confirming the model fit of the structural model, Figure 3 and Table 4 both showed the results of hypothesized path testing of the structural relationships.

As shown, eight hypotheses were supported and two were rejected. Hypothesis 1 posited that PU positively influences IAFT. As predicted, we found that IAFT was positively influenced by PU (β = 0.195, p < .05), providing support for Hypothesis 1. From Hypotheses 3 and 4, PEOU positively affected PU (β = 0.725,

p< .001) and PP (β = 0.495, p < .001). Hypotheses 3 and 4 are strongly supported

by the data. Likewise, in Hypothesis 5, the relationship of PP to IAFT was also supported with a high level of significance (β = 0.368, p < .001). Moreover, the paths from PA to PP (β = 0.414, p < .001) and IAFT (β = 0.150, p < .01) were posi-tive and significant, thereby supporting H6 and H7. Turning to Hypothesis 8, SN had a significant effect on PU (β = 0.135, p < .01). Accordingly, Hypothesis 8 was supported. Furthermore, PCM was found to significantly affect IAFT (β = 0.153,

p< .01), supporting Hypothesis 10. Unexpectedly, PEOU and SN had no direct

influence on IAFT. Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 9 were not supported. Finally, the results illustrate that our model approximately explained 62% of the variance in PU, 60% of the variance in PP, and 44% of the variance in IAFT, all of which indicated that our research model has a reasonable explanatory power.

Table 5 also summarized the direct, indirect, and total effects of variables on IAFT. PP had the largest direct effect (0.368) on IAFT as well as total effect.

Intention to Adopt Fashion Technology

(R2=0.438)

Perceived Critical Mass Social Norms

Social and Psychological Factors

0.195* 0.725***

0.495***

0.368*** Perceived Usefulness (R2=0.616)

Perceived Ease of Use

–0.017 Perceived Playfulness (R2=0.601) Perceived Aesthetics Ergonomic Factors 0.414*** 0.150** 0.008 0.153** 0.135** Significant path Insignificant path * P-value<0.05 ** P-value<0.01 *** P-value<0.001

FIGURE 3 Research model.

Table 4: The Results of the Hypotheses Test

Path Coefficients SE Significance Results

H1 PU→IAFT 0.195 0.120 .012∗ Supported H2 PEOU→IAFT −0.017 0.100 .846 Not supported H3 PEOU→PU 0.725 0.041 .000∗∗∗ Supported H4 PEOU→PP 0.495 0.037 .000∗∗∗ Supported H5 PP→IAFT 0.368 0.092 .000∗∗∗ Supported H6 PA→PP 0.414 0.034 .000∗∗∗ Supported H7 PA→IAFT 0.150 0.061 .006∗∗ Supported H8 SN→PU 0.135 0.045 .004∗∗ Supported

H9 SN→IAFT 0.008 0.085 .891 Not supported H10 PCM→IAFT 0.153 0.060 .002∗∗ Supported

Note. PU= perceived usefulness; IAFT = intention to adopt fashion technology;

PEOU= perceived ease of use; PP = perceived playfulness; PA = perceived aesthetics; SN= social norms; PCM = perceived critical mass.

∗p< .05.∗∗p< .01.∗∗∗p< .001.

Meanwhile, PA, with direct and indirect effects through PP, had a total effect of 0.302 on IAFT. PEOU, however, did not have a significant direct effect on IAFT, but it still exhibited secondary large total effect (0.306) through PU (0.141) and PP (0.182) on IAFT. Comparatively, social norms had a very weak total effect on that intention.

Table 5: Effects on the Intention to Adopt Fashion Technology

Construct Direct Effects Indirect Effects Total Effects

Perceived ease of use −0.017 0.141 0.306 0.182

Perceived usefulness 0.195 0.195

Perceived playfulness 0.368 0.368

Perceived aesthetics 0.150 0.152 0.302

Social norms 0.008 0.026 0.034

Perceived critical mass 0.153 0.153

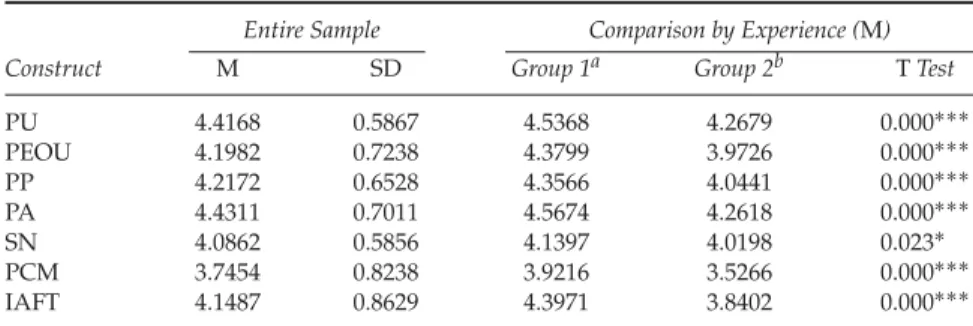

Table 6: Perception Differences in Experiences Comparison

Entire Sample Comparison by Experience (M)

Construct M SD Group 1a Group 2b T Test

PU 4.4168 0.5867 4.5368 4.2679 0.000∗∗∗ PEOU 4.1982 0.7238 4.3799 3.9726 0.000∗∗∗ PP 4.2172 0.6528 4.3566 4.0441 0.000∗∗∗ PA 4.4311 0.7011 4.5674 4.2618 0.000∗∗∗ SN 4.0862 0.5856 4.1397 4.0198 0.023∗ PCM 3.7454 0.8238 3.9216 3.5266 0.000∗∗∗ IAFT 4.1487 0.8629 4.3971 3.8402 0.000∗∗∗

Note. Group 1: adopters, Group 2: potential adopters. PU= perceived usefulness;

PEOU= perceived ease of use; PP = perceived playfulness; PA = perceived aesthetics; SN= social norms; PCM = perceived critical mass; IAFT = intention to adopt fashion tech-nology.

aN= 272.bN= 219.

∗p< .05.∗∗∗p< .001.

Table 6 displays the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) of the constructs. It can be found that, on average, participants respond to the feel-ing of the Apple iPod in a clearly positive manner (the averages of all constructs were greater than three out of five). Next, to further explore the experience differ-ences in the perceptions of the fashion technology, we divided our sample into two independent groups based on their prior experience of adopting an Apple iPod: adopters (Group 1) and potential adopters (Group 2). All the individuals with no experience adopting the Apple iPod were thus included in Group 2, whereas the rest were put in Group 1. Using the independent-samples T test, we analyzed the effects of the experience difference on the PU, PEOU, PP, PA, SN, PCM, and IAFT constructs. Significant experience differences were founded for all variables. The results (means) showed that adopters’ ratings were significantly higher than potential adopters’.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our research sought to explore the impact of ergonomic and social psychologi-cal on user intention to adopt and use a fashion technology. To address this issue,

we advanced a research model that included the construct of perceived useful-ness, ease of use, playfuluseful-ness, and aesthetics as the ergonomic factors. We also treated social norms and perceived critical mass as the social and psychological variables. The Apple iPod was chosen for this study because it is a well-known and fashionable information technology that lends its success in the market due to its stylish and high-tech elements. The proposed model was tested by a structural equation modeling approach. The study was strongly confirmed with adequate reliability, validity, and well-predictive power. Broadly speaking, most path coef-ficients in the model were found to be statistically significant except for the factors of PEOU and SN to intention. From an ergonomic perspective, an interesting find-ing was that users were willfind-ing to adopt fashion technology because of usefulness, playfulness, and aesthetics. Contrary to expectations, the result of the relationship between PEOU and IAFT were insignificant. In the case of the portable media device, it suggests that being easy to use is not a prominent characteristic to attract users to adopt them in these mature stages of markets. However, the usefulness, playfulness, and aesthetic characteristics will allow users to have motivations and increase IAFT. In addition, from a social psychological perspective, the results revealed that only PCM affects the users’ intentions toward fashion technology. However, SN did not have a significant direct effect on behavioral intention. Most potential users and adopters were more fairly “pragmatic” and made their own decisions from public tendencies rather than by blindly following responses from friends or relatives. This finding is different from the theories of TRA and TPB. The first explanation is that the usage of fashion technology is not a mandatory behavior, and thus SN may have impact on perceptions rather than intentions for adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003). The other possible explanation is the need for uniqueness. This is because individuals may try to move away from the norms’ opinions to show their personal identity and pursuit of differentiation, especially for fashion technologies (Hassenzahl, Burmester, & Koller, 2003; Snyder, 1992).

5.1. Implications

From a theoretical point of view, the purpose of this study was to propose and verify a model for adoptive intention in a fashion technology domain. The main contributions of the current work are fivefold. First, this study is a pioneering effort in incorporating technology acceptance and social diffusion viewpoints into the newly emerging context of fashion technology. This is a new breakthrough in IT-related literature. We found that not only did usefulness, playfulness, and aesthetics play significant positive influences on behavioral intentions to adopt fashion technology, but PCM from social psychological perspective may also have a positive effect on it. Second, PP is the factor with the greatest significant effect on IAFT. It implied that potential users and adopters were more likely to use a fash-ion technology when they felt that it was more playful. Therefore, we suggest that PP (enjoyment) should be considered as a crucial factor when investigating the individual adoptive behavior of hedonic systems, especially fashionable technolo-gies. Third, although ease of use is not a direct predictor for fashion technology adoption, it still had a large total effect through usefulness and playfulness on the intention to adopt. Hence, PU and PP could be viewed as the complete mediators

between the PEOU and BI. Fourth, our research also showed that PA had both a direct and indirect effect through PP (partial mediator) on IAFT. These findings support the previous study (Berlyne, 1971) indicating that there is a positive rela-tionship between pleasure and level of interest. It can be interpreted that when potential users perceive the appearance of fashion technology as being beautiful and well designed, they will feel enjoyment while having positive intentions to adopt it in the future. Fifth, our results confirm Rogers’s study: The effect of a crit-ical mass was not only an important factor in interactive technologies but also a salient variable in fashion technologies acceptance.

Our article also contributes to practice. First, the results indicate that “perceived playfulness” and “perceived aesthetics” are the top two significant roles in devel-oping the users’ intention to adopt fashion technology. These findings shed light on the distinctive features of fashion technologies: Interesting functions and fas-cinating appearance are the drivers of the fashion technologies. Likewise, these relationships also show that hedonic rather than technical factors are most impor-tant in the fashion technology industry, whereas the technical facets are the basic threshold. In Bloch’s (1995) study, he suggested that the physical shape or design of a product is an undisputed determinant of its marketplace success. Therefore, today’s fashion technology designers should work hard to design technologies that are aesthetic and playful, combining some enjoyable information and stylish form, and then intrigue more potential users to adopt that technology. Second, the effects of usefulness and ease of use from TAM were verified in our study. Even though PEOU is an insignificant factor in the results, it still had the sec-ond largest total effect on IAFT. Thus, attention for practitioners must be placed on designing a user-friendly interface, useful functions and detailed operating manual, and so on, because the ergonomic factors are the basic threshold for fash-ion technology acceptance (Rogers, 1995). Third, our study found that adopters and potential adopters are significantly different in their perceptions of fash-ion technology. Adopters had the higher perceptfash-ions as compared to potential adopters. Therefore, it is important for the decision makers of companies with fashion technology to raise the consumers’ overall awareness. They should attend to devoting themselves to building a well-known image and reputation, especially for potential users. Finally, as the results showed, PCM had a direct impact on user intentions. It meant that an individual will more likely have the intention to adopt an Apple iPod when he or she perceives that many people use it. As an individual believes that there are many people who adopt an innovation, he or she will be willing to use it because of its stable quality, rich shared usage experience, and abundant postpurchase services and complementary gadgets (Katz & Shapiro, 1985). Consequently, for marketing managers, to encourage more potential users to adopt the fashion technology, these results suggest that achieving critical mass is an important and essential marketing strategy that will determine the success or failure of a business.

5.2. Limitations

Although our work provides some academic and practical insights, some limi-tations must be considered. The first limitation concerns the sample used in the

current study. The volunteer respondents were all from Taiwan and self-selected via an online-based convenient sampling. Because of this, one should be cautious of generalization, because cultural and lifestyle differences may influence users’ perceptions and intentions. In addition, we also suggested that future research could use a random sampling approach to collect research data. Second, the results were limited to the users’ opinions of the Apple iPod. When generalizing the find-ings and discussions to other fashion technologies, care needs to be taken. Third, our study is a cross-sectional quantitative research; thus conducting a longitudinal approach in the future is a good way to understand the change of users’ inten-tions over time. Last, this study focused only on technology acceptance and social diffusion standpoints. Other additional dimensions (such as perceived brand, monetary value, and personal innovativeness) may affect users’ intentions and should be identified in future studies.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R., & Karahanna, E. (2000). Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Quarterly, 24, 665–692. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 50, 179–211.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Apple. (2008). Apple introduces new iPod nano: Fourth generation iPod nano features Apple’s new

genius technology. Retrieved from http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2008/09/09nano.

html

Atkinson, M. A., & Kydd, C. (1997). Individual characteristics associated with World Wide Web use: an empirical study of playfulness and motivation. ACM SIGMIS Database, 28(2), 53–62.

Barnett, L. A. (1990). Playfulness: Definition, design, and measurement. Play and Culture, 3, 319–336.

Breaden, W. O., & Etzel, M. J. (1982). Reference group influence on product and brand purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 183–194.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and psychobiology. New York, NY: Meredith.

Bloch, P. H. (1995). Seeking the ideal form: product design and consumer response. The

Journal of Marketing, 59, 16–29.

Bock, G., Zmud, R. W., & Kim, Y. (2005). Behavioral intention in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social psychological forces, and organiza-tional climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111.

Carayon-Sainfort, P. (1992). The use of computers in offices: Impact on task characteristics and worker stress. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 4, 245–261. Chau, P. Y. K. (2001). Influence of computer attitude and self-efficacy on IT usage behavior.

Journal of End User Computing, 13(1), 26–33.

Childers, T. L., & Rao, A. R. (1992). The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 198–211.

Cohen, P. (2006). Study: iPod dominance unthreatened for 18 months. Retrieved from http://www.macworld.com/article/53561/2006/10/dominance.html

Cyr, D., Bonanni, C., Bowes, J., & Ilsever, J. (2005). Beyond trust: Web site design preferences across cultures. Journal of Global Information Management, 13(4), 25–54.

Cyr, D., Head, M., & Ivanov, A. (2006). Design aesthetics leading to m-loyalty in mobile commerce. Information & Management, 43, 950–963.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 319–340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of com-puter technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35, 982–1003.

Davis, F. D., & Venkatesh, V. (1996). A critical assessment of potential measurement biases in the technology acceptance model: Three experiments. International Journal of Human–

Computer Studies, 45(1), 19–45.

Dickinger, A., Arami, M., & Meyer, D. (2008). The role of perceived enjoyment and social norm in the adoption of technology with network externalities. European Journal of

Information Systems, 17(1), 4–11.

Fang, X., Chan, S., Brzezinski, J., & Xu, S. (2006). Moderating effects of task type on wireless technology acceptance. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22, 123–157.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief , attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory

and research. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobserv-able variunobserv-ables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. Ha, I., Yoon, Y., & Choi, M. (2007). Determinants of adoption of mobile games under mobile

broadband wireless access environment. Information & Management, 44, 276–286. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis:

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hassenzahl, M. (2004). The interplay of beauty, goodness, and usability in interactive products. Human–Computer Interaction, 19, 319–349.

Hassenzahl, M., Burmester, M., & Koller, F. (2003). AttrakDiff: Ein Fragebogen zur Messung

wahrgenommener hedonischer und pragmatischer Qualitat. Paper presented at the Mensch &

Computer 2003: Interaktion in Bewegung, September 2003, Stuttgart, Germany. Hatcher, L. (1994). A step-by-step approach to using the SAS system for factor analysis and

structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Herrero Crespo, A., & Rodriguez del Bosque, I. (2008). The effect of innovativeness on the adoption of B2C e-commerce: A model based on the theory of planned behaviour.

Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 2830–2847.

Hong, S. J., & Tam, K. Y. (2006). Understanding the adoption of multipurpose information appliances: The case of mobile data services. Information Systems Research, 17, 162–179. Hong, W., Thong, Y. L. J., Wong, W. M., & Tam, K. Y. (2002). Determinants of user

accep-tance of digital libraries: An empirical examination of individual differences and system characteristics. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18, 97–124.

Horton, R. P., Buck, T., Waterson, P. E., & Clegg, C. W. (2001). Explaining intranet use with the technology acceptance model. Journal of Information Technology, 16, 237–249.

Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2008). Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology accep-tance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Information & Management,

45(1), 65–74.

Hsu, C. L., & Lu, H. P. (2004). Why do people play on-line games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. Information & Management, 41, 853–868.

Hsu, C. L., & Lu, H. P. (2007). Consumer behavior in online game communities: A motiva-tional factor perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 1642–1659.

Igbaria, M., Parasuraman, S., & Baroudi, J. J. (1996). A motivational model of microcom-puter usage. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(1), 127–143.

Jeyaraj, A., Rottman, J. W., & Lacity, M. C. (2006). A review of the predictors, linkages, and biases in IT innovation adoption research. Journal of Information Technology, 21(1), 1–23. Jordan, P. W. (1998). Human factors for pleasure in product use. Applied Ergonomics, 29(1),

25–33.

Karvonen, K. (2000). The beauty of simplicity. Proceedings of the 2000 Conference on Universal

Usability, 85–90.

Katz, M. L., & Shapiro, C. (1985). Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. The

American Economic Review, 75, 424–440.

Katz, M. L., & Shapiro, C. (1986). Technology adoption in the presence of network externalities. The Journal of Political Economy, 94, 822–841.

Kim, K. (1998). Philosophical discussion on the science of emotion and sensibility. The

Korean Society for Emotion and Sensibility, 1(1), 3–11.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd. ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Lavie, T., & Tractinsky, N. (2004). Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 60, 269–298.

Lee, D., Rhee, Y., & Dunham, R.B. (2009). The role of organizational and individual char-acteristics in technology acceptance. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction,

25, 623–646.

Lee, J. J. (2007). Newly-appointed president of samsung (Taiwan), Announced aggressive plans

regarding mobile phones and MP3 players sectors for Taiwan’s market. Retrieved from

http://cti.acesuppliers.com/news/new_1_10.html

Lee, K. C., Kang, I., & Kim, J. S. (2007). Exploring the user interface of negotiation sup-port systems from the user acceptance perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(1), 220–239.

Lieberman, J. N. (1977). Playfulness: Its relationship to imagination and creativity. New York: Academic Press.

Lin, C., Shih, H., & Sher, P. J. (2007). Integrating technology readiness into technology acceptance: The TRAM model. Psychology & Marketing, 24, 641–657.

Lin, C. S., Wu, S., & Tsai, R. J. (2005). Integrating perceived playfulness into expectation-confirmation model for web portal context. Information & Management, 42, 683–693. Lindgaard, G., & Dudek, C. (2003). What is this evasive beast we call user satisfaction?

Interacting with Computers, 15, 429–452.

Liu, C., & Arnett, K. P. (2000). Exploring the factors associated with web site success in the context of electronic commerce. Information & Management, 38(1), 23–33.

López-Nicolás, C., Molina-Castillo, F. J., & Bouwman, H. (2008). An assessment of advanced mobile services acceptance: Contributions from TAM and diffusion theory models.

Information & Management, 45, 359–364.

Lou, H., Luo, W., & Strong, D. (2000). Perceived critical mass effect on groupware accep-tance. European Journal of Information Systems, 9, 91–103.

Lucas, H. C., & Spitler, V. K. (1999). Technology use and performance: A field study of broker workstations. Decision Sciences, 30, 291–311.

Mahler, A., & Rogers, E. M. (1999). The diffusion of interactive communication innovations and the critical mass: the adoption of telecommunications services by German banks.

Telecommunications Policy, 23, 719–740.

Martocchio, J. J., & Webster, J. (1992). Effects of feedback and cognitive playfulness on performance in microcomputer software training. Personnel Psychology, 45, 553–578. Moon, J. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2001). Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context.

Information & Management, 38, 217–230.

Nisbet, S. L. (2006). Modelling consumer intention to use gambling technologies: an innovative approach. Behaviour & Information Technology, 25, 221–231.

Ong, C. S., & Lai, J. Y. (2006). Gender differences in perceptions and relationships among dominants of e-learning acceptance. Computers in Human Behavior, 22, 816–829.

Park, S., Choi, D., & Kim, J. (2004). Critical factors for the aesthetic fidelity of web pages: Empirical studies with professional web designers and users. Interacting with Computers,

16, 351–376.

Pettit, F. A. (2002). A comparison of World-Wide Web and paper-and-pencil personality questionnaires. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 34(1), 50–54. Premkumar, G., Ramamurthy, K., & Liu, H. N. (2008). Internet messaging: An

examina-tion of the impact of attitudinal, normative, and control belief systems. Informaexamina-tion &

Management, 45, 451–457.

Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: Free Press. Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: Free Press.

Schenkman, B. N., & Jonsson, F. U. (2000). Aesthetics and preferences of web pages.

Behaviour & Information Technology, 19, 367–377.

Scott, J. E. (1995). The measurement of information systems effectiveness: Evaluating a measuring instrument. ACM SIGMIS Database, 26(1), 43–61.

Shang, R. A., Chen, Y. C., & Shen, L. (2005). Extrinsic versus intrinsic motivations for consumers to shop on-line. Information & Management, 42, 401–413.

Shin, D. H. (2009). Determinants of customer acceptance of multi-service network: An implication for IP-based technologies. Information & Management, 46(1), 16–22.

Snyder, C. R. (1992). Product scarcity by need for uniqueness interaction: A consumer catch-22 carousel? Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 13(1), 9–24.

Song, J., & Wladen, E. (2007). How consumer perceptions of network size and social inter-actions influence the intention to adopt peer-to-peer technologies. International Journal of

E-Business Research, 3(4), 49–66.

Strader, T. J., Ramaswami, S. N., & Houle, P. A. (2007). Perceived network externalities and communication technology acceptance. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(1), 54–65.

Tian, K. T., Bearden, W. O., & Hunter, G. L. (2001). Consumers’need for uniqueness: scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 50–66.

Tractinsky, N., Cokhavi, A., Kirschenbaum, M., & Sharfi, T. (2006). Evaluating the con-sistency of immediate aesthetic perceptions of web pages. International Journal of

Human–Computer Studies, 64, 1071–1083.

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10.

Van der Heijden, H. (2003). Factors influencing the usage of websites: The case of a generic portal in the Netherlands. Information & Management, 40, 541–549.

Van der Heijden, H. (2004). User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS Quarterly,

28, 695–704.

Van Slyke, C., Ilie, V., Lou, H., & Stafford, T. (2007). Perceived critical mass and the adoption of a communication technology. European Journal of Information Systems, 16, 270–283. Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control,

intrin-sic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems

Research, 11, 342–365.

Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46, 186–204.

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior.

MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115–139.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478.

Webster, J., & Martocchio, J. J. (1992). Microcomputer playfulness: Development of a measure with workplace implications. MIS Quarterly, 16, 201–226.

Weisbein, J. (2008). The iPod success: Thank the marketing department. Retrieved from http:// www.besttechie.net/2008/03/01/the-ipod-success-thank-the-marketing-department/ Wixom, B. H., & Todd, P. A. (2005). A theoretical integration of user satisfaction and

technology acceptance. Information Systems Research, 16(1), 85.

Yamamoto, M., & Lambert, D. R. (1994). The impact of product aesthetics on the evaluation of industrial products. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11, 309–324.

Yi, M. Y., Jackson, J. D., Park, J. S., & Probst, J. C. (2006). Understanding information tech-nology acceptance by individual professionals: Toward an integrative view. Information

& Management, 43, 350–363.

Appendix A

Table A1: List of Model Constructs and Items

Perceived Usefulness (M= 4.42, SD = 0.59)

(PU1) I believe that I can listen to music anytime anywhere by using the Apple iPod. (PU2) I believe that using the Apple iPod enables me to conveniently listen to music. (PU3) I believe that using the Apple iPod to listen to music can help me kill time. Perceived Ease of Use (M= 4.20, SD = 0.72)

(PEOU1) I believe that it is easy to use the Apple iPod to listen to music. (PEOU2) I believe that using the Apple iPod to listen to music is effortless.

(PEOU3) It is easy for me to become skillful at using the Apple iPod to do anything I want. Perceived Playfulness (M= 4.22, SD = 0.65)

(PP1) I believe that using the Apple iPod brings me fun. (PP2) I believe that using the Apple iPod keeps me happy. (PP3) I believe that using the Apple iPod gives me enjoyment. Perceived Aesthetics (M= 4.43, SD = 0.70)

(PA1) I think the appearance of the Apple iPod is attractive. (PA2) I think the appearance of the Apple iPod is well designed. (PA3) I think the appearance of the Apple iPod is interesting. Social Norms (M= 4.09, SD = 0.59)

(SN1-Dropped) My family suggests that I should use Apple iPod. (SN2) My friends suggest that I should use Apple iPod.

(SN3) My colleagues (classmates) suggest that I should use Apple iPod. Perceived Critical Mass (M= 3.75, SD = 0.82)

(PCM1) I believe many people use the Apple iPod.

(PCM2) I think many people I communicate with frequently use the Apple iPod. (PCM3) In my opinion, there are a lot of people who use the Apple iPod. Intention to Adopt Fashion Technology (M= 4.15, SD = 0.86)

(IAFT1) I have the intention to use an Apple iPod.

(IAFT2) I am willing to use an Apple iPod in the near future. (IAFT3) Overall, I have a strong desire to use an Apple iPod.

Appendix B

Table B1: GFI Indices for the Research Model

Index Recommended Value Measurement Model Results Structural Model Results

χ2/df <3 413.262/149 = 2.774 448.801/154= 2.914 GFI >0.9 0.924 0.917 AGFI >0.8 0.892 0.887 NFI >0.9 0.940 0.935 TLI >0.9 0.950 0.946 CFI >0.9 0.961 0.956 RMSEA ≤0.06 or ≤0.08 0.060 0.063

Note. GFI= goodness of fit index; AGFI = the adjusted GFI; NFI = normed fit index;

TLI= Tucker–Lewis index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.