行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

測驗評量與英語學習動機的關聯─理論構念的澄清與實證

研究

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 96-2411-H-004-047- 執 行 期 間 : 96 年 08 月 01 日至 98 年 01 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學外文中心 計 畫 主 持 人 : 黃淑真 計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:吳和典 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳姿惠 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:曾湘茹 大專生-兼任助理人員:陳智鈞 大專生-兼任助理人員:鄭景文 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:朱希亮 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 98 年 04 月 30 日

Introduction

Studies on second/foreign language (L2) learning motivation, after the “educational shift” in the 1990s (Dörnyei, 2001a; p. 104), may be characterized by an attempt to move beyond the social psychological emphasis of classical L2 motivation theories. Two breakthroughs are observed since then. First, teachers’day-to-day classroom practice has been taken into consideration, as exemplified in Dörnyei (2001b), and more recently in empirical studies of observable teacher behaviors such as Cheng and Dörnyei (2007) and Guillotezux and Dörnyei (2008). Secondly, the dichotomy of integrative/instrumental orientation (Gardner, 1985) has been reinterpreted (e.g. Csizer & Dörnyei, 2005; Lamb, 2007) and expanded to include aspects that were neglected before. These endeavors assist us in strengthening theory and also bridging the gap between theory and practice. However, the aforementioned development is not without limitations. For example, studies of teacher classroom behaviors tend to focus less on

unobservable teacher decision making, which may have as strong an impact on students’learning experiences as observable teacher behaviors. In addition, although some additional motivational attributes were identified, follow-up discussion and investigation is still insufficient.

The current study is intended to discuss one such aspect of L2 learning, that is, classroom assessment, also closely related to the concept of “requirement motivation”(Ely, 1986; Warden & Lin, 2000) and explore the necessity of its inclusion in L2 teachers’motivational arsenal. In this paper, I first review the concept “requirement motivation”in past L2 motivation studies.

Secondly, I describe in detail the reality in a “test-driven”society and how it relates to classroom teaching and learning. Third, I argue that such phenomenon is not exclusively “Chinese”or “Asian”, even though some variation in magnitude exists. Fourth, I provide a literature review on “assessment FOR learning”, classroom assessment motivation theories, as well as student

reaction to test requirement. Finally, I present my investigation on L2 teachers’classroom assessment practice and rationale as well as students’opinions on teachers’“motivating effort through tests”conception in an Asian context.

Requirement Motivation

In earlier research efforts to describe students’L2 learning motivation, Ely (1986) is probably the first in identifying a “requirement motivation”cluster, in addition to the integrative and instrumental orientations, among first-year American college students of Spanish. That is to say, some students’motivation for learning an L2 is simply because it is required for the

completion of their education. He observed a weak but negative relation between this third cluster and the strength of student motivation. Therefore, Ely called for more careful consideration in implementing L2 requirements.

Warden and Lin (2000), in a foreign language context, found the integrative orientation to be almost nonexistent among Taiwanese college students of English. Instead, instrumental and requirement motivation appear to be the major reasons why students learn English. They further point out that such motivational orientations are mirrored in the local private language learning industry, with one type focusing specifically on job preparation such as business English (instrumental) and another on passing all types of entrance examinations (requirement).

Chen, Warden, and Chang (2005), along the same track, found that requirement motivation, rather than instrumental, had thestrongestrelation to students’expectancy, and associate the observed requirement motivation with a collective pursuit for outstanding test results in the Chinese society. They discuss in detail the overarching social value for success on exams and the consequent honor brought to the entire family. EFL teachers having received professional training from western countries, they caution, if unaware of local students’true motivation, may be misled by western theories and thus could not address students’needs fully. Based on their analysis, Chen et al. (2005) coined a term “Chinese Imperative”to represent the “requirement motivation” that may exist in the greater Chinese societies.

More recently, Price and Gascoigne (2006) conducted a survey on American college students’perceptions and beliefs toward foreign language requirement. They consider that a total of 57% positive attitude for the requirement a sign of improvement and very encouraging. However, still 22% held a negative attitude and 21% were ambivalent, amounting to a total of 43%. Almost half of the students sampled felt that foreign language study was a requirement imposed on them. Based on student opinions, the authors further expanded Ely’s (1986)

requirement cluster into a long list of reasons (con to be compared with pro) why students think foreign language requirement is not a viable idea.

All the survey results notwithstanding, Warden and Lin’s (2000) genuine question –“Can a ‘requirement motivation’be taken advantage of in EFL teaching?”(p. 544) remains largely unanswered after a decade. When learners take language study as merely a requirement, they are most concerned with obtaining the credits. If writing an exam and getting a 60 point will get her the credits, she will try to fulfill her obligations. If other things are required, she will most likely comply. The grade granted by the course instructor and the learning activities underlying the grade is a mighty tool teachers are endowed with on this job. Nevertheless, the concept of “requirement motivation”, despite its being identified in very different learning contexts, did not receive much subsequent research attention. It may have to do with the contradictory nature of the term and concept itself. One may claim that if a learner is “motivated”by institutional requirements, then this student is not motivated to learn. This student is lack of intrinsic

motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985), which may be the key to eventual achievement. Requirement motivation, unlike “true”motivation, sounds likely an antecedent of failure. Abundant evidence in educational literature repeatedly warns teachers of the possible negative consequences of utilizing extrinsic motivation, such as learners’pursuit of rewards and avoidance of punishment,

especially in the long run. Therefore, requirement would not seem a plausible way to motivate students. Teachers’ideal image of students would be one who comes into the classroom with ultimate interests in learning the target language. Facing such a learner, a teacher can stimulate her interest and aim for higher-level development. To most teachers, unfortunately, this rarely happens. In the following section, I will follow up on Chen et al.’s (2005) “Chinese Imperative” concept and further describe the current social phenomenon in more detail.

A “Test-driven”Educational Milieu

In addition to Chen et al.’s (2005) discovery of students’strong requirement motivation and its association with a collective pursuit of high marks on examinations and the consequent honor lauded on family and clans, in a more recent report, Shih (2008) describes a locally-developed proficiency test, General English Proficiency Test, in Taiwan and how it evolves into a

nationwide activity within a decade. High school and college entry and exit policy makers as well as government institution officials are afraid to fall behind in requiring or encouraging students and employees to pursue exam certificates. “As an examination-oriented society in which people believe that tests can successfully drive students to study, Taiwan has fallen into an

unprecedented test mania. (Shih, 2008; p.73)”

When exam results become a major determinant for very competitive high school and college admission, job acquirement, and other resource competing events, and the situation persists throughout the entire life span of academic and professional pursuit, the associated pressure for learners is enormous. It may be hard for people outside of this social milieu to imagine how students would try to get away from study at the very slight chance when tests are not an immediate threat upon them. A common way parents deter teenage children from

extracurricular activities, part-time jobs, romantic relationships, and other activities not related to high schooland collegeentranceexam would be“wait until you enter a good college.”

“University”used to be translated by its pronunciation into Chinese as

“play-four-years-as-you-wish”(you-ni-wan-si-nien) because the college entrance exam wore out young students’energy for at least six years and, once admitted into the “narrow gate”, students consider themselves privileged for some relaxed fun time. This term is not used as often now, since nowadays college admission rate is much higher than before, and therefore tests and competition continue beyond the undergraduate level. This widespread exam-oriented mentality had made endeavors such as communicative language teaching and formative assessment more difficult, even at the tertiary level. In order to draw learners’attention to their academic work, teachers usually turn back to tests again, creating a seemingly endless vicious cycle.

Not Just “Chinese”

The “test as the priority”mentality is by no means exclusively Chinese. The scenario depicted above is no news in many other Asian contexts. According to a recent survey of English

exams in Korea (Choi, 2008), the consequence of high valuation on exam has reached the extent of overriding learning itself. Exam results are used for screening and placement purposes in secondary school and college admission, graduation, as well as job offers. To pass various standardized proficiency tests and get high marks on these tests become the number one priority for many adolescent and adult EFL learners. As exemplified in the Korean survey (Choi, 2008), half of the secondary school teachers asking their pupils to take proficiency tests claimed that the purpose is “to motivate students to study English”, followed by another 25% of “to help students improve English skills”(p. 54). In Hong Kong, Davison (2007), in describing the effort to enable positive washback in English language school-based assessments in Hong Kong, vividly

illustrates how “fairness”became a sociocultural, or even political, issue, rather than a simple technical one, when the benign intention of exam reform is viewed through parents’very critical eyes. For many students, immersed under such social pressure and social values, the most

dominant principle may be subsumed as “points talk”, a term derived from “money talks”coined by a native English speaking teacher to describe Taiwanese students’attitude toward grades in her English classes (Sheridan, 2009).

In fact, the idea of “testing to motivate effort”is not constrained in certain geographical areas. With negative connotation, some western scholars note that assessment would motivate by intimidation (Stiggins, 1999). In an earlier literature review on classroom evaluation practices, Crooks (1988) systematically review lots of research from the sixties to eighties. Many

demonstrated that what teachers advocate in the classroom do not influence students as much as what and how they actually assess students. Learners are usually very conscious about how they are evaluated and adjust their study behaviors accordingly. Therefore, it is said that the best way to change student study habits is to change test methods. Empirical studies on effects of

classroom evaluation strategies such as ways to administer quizzes are all over the general education literature (e.g. Kouyoumdjian,2004; Olina & Sullivan, 2002; Ruscio, 2001).

Assessment FOR Learning

Although there is a widespread acceptance that testing is harmful for learning motivation and lifelong learning (Harlen & Crick, 2003; Remedios, Ritchie, & Lieberman; 2005), this conviction is mostly directed to high-stakes summative tests. Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam (2004) reviewed over 250 published articles on formative assessments and concluded with an unequivocal positive answer to the question on the potential of Assessment FOR Learning (AFL), as opposed to assessment OF learning, in the classroom. Classroom assessment studies are varied with different purposes. Brookhart (2004) describes them as unfocused “patchworks” scattered all over the map. From her analysis, except some showing no theoretical support, thus falling into mere reports of classroom practices, many fall under three major frameworks. Among 57 selected articles, 88% of review articles and 60% of empirical studies were framed under psychological and individual differences theories, in particular, learning and motivation theories. More specifically, theories about the role of classroom assessment in student motivation and

achievement (Brookhart, 1997; Brookhart & DeVoge, 1999) are being developed since traditional testing and measurement theories are inadequate in addressing the constituent and dynamic nature of classroom environments (Brookhart, 2004; Leung, 2004).

When the results of various forms of classroom assessment, both tests and non-tests, and ultimately the grades students earn from these activities, lead to the successful or unsuccessful acquirement of credits and the completion or incompletion of program requirement, stakeholders involved pay conscious attention to how institutional course requirement is translated by teachers into tests and homework in the classroom, and eventually how grades are assigned. Relevant research can be divided into those studying teacher assessment and grading practices and those studying student adaptation of study strategies. On the teachers’side, recent studies (Cross & Frary, 2000; McMillan, Myran, & Workman, 2002; Zhang & Burry-Stock, 2003) refer to the observed teacher grading practice a “hodgepodge”(Brookhart, 1991; p. 36) of attitude, effort and achievement. Although scholars point out its incongruity against recommendations of

measurement specialists, i.e. providing unbiased, valid and truthful indicators of academic achievement, they found this practice to be common among teachers, regardless of teachers’ measurement training and despite that fact that assessment practices are found to be

individualistic and vary greatly from one teacher to another. In addition, students as well as parents endorse such “hodgepodge”practices because of the perceived need to “manage

classrooms and motivate students”(Brookhart, 1994; p.299). The applicability of testing theories in real classrooms is questioned and therefore the need for additional research is acknowledged.

Studies on student adaptation indicate that although some students study the same way regardless of how they are tested (“cue deaf”, Miller & Parlett, 1974), the majority of students at the college level exercise conscious coping strategies in response to test formats (“cue seeker”, Miller & Parlett, 197) (Broekkamp, Van Hout-Wolters, 2007; Natriello, 1987; Van Etten, Freebern, & Pressley, 1997). Knowing what and how they would be tested provides critical information when students determine their study strategies. Van Etten et al. (1997) survey 142 undergraduates and report that “examinations per se motivate studying”(p. 200) because students want to obtain good grades. Their study behavior is closely tied to their own cost-benefit analysis between expected results and a myriad of factors including prior knowledge, self-efficacy,

difficulty level, etc. Most of these factors show a curvilinear relationship with student effort. That is to say, in order to motivate effort, the test or task requirement should not be considered too difficult or too easy by them so that effort will make a difference in the results. A long list of suggestions are summarized on how classroom tests can be modified to be more educationally friendly, including giving models of good work, plenty advance warning, emphasizing personal progress rather than competition, making sure effort rather than prior knowledge would be credited, etc.

One thing to be discerned is the domain-specific nature of classroom assessments. In 2004 in the journal of Language Testing, Harlen and Winter report findings from science and

mathematics classrooms and introduce the idea of AFL to language teachers. Harlen and Winter indicate that most of these studies, including those reviewed in this paper, concern how classroom assessment may benefit learning and they are mostly from primary and secondary contexts with a focus on science, mathematics, or language arts (first language) instruction. Although some findings on techniques and strategies may be borrowed from one discipline to another, the core abilities desired in each domain are different and have to be defined clearly before we examine disciplinary-specific assessment content and tasks. For example, projects and experiments may help cultivate the abilities desired in science and practice problems may serve the purpose of mathematics learning better. The study on how L2 classroom assessment may benefit learning, however, is scarce among the AFL literature. In the area of L2, formative assessment (FA), or teacher assessment, classroom assessment, is more commonly used to describe the work on orienting assessments to serve the purpose of learning and teaching (e.g. Colby-Kelly & Turner, 2007; Leung, 2004; Rea-Dickins & Gardner, 2000), although other related concepts such as dynamic assessment (Lantolf & Poehner, 2004; Leung, 2007; Poehner, 2007) have started to gain research attention. Leung (2004) contends that as FA rekindles policy and research interests, there are a lot of “theoretical, infrastructural, and teacher development work”to be done (p. 38). More specifically, if concepts such as “reliability”and “validity”from traditional testing theories are not plausible for learning-oriented classroom assessments, how are we going to study FA and ask the right questions? Many epistemological issues need to be addressed before we can proceed in the study of AFL in the L2 contexts.

The Study

The current study was set out to examine the viability of studying the interface between motivation and classroom assessment in foreign language learning. EFL teachers’practice and rationale as well as EFL students’perspectives were sought to help us understand how pervasive and formidable the “testing to motivate”mentality exists in college EFL classrooms. More specifically, the following research questions would be answered.

1. Did college EFL teachers in Taiwan try to motivate student effort by tests and grades? How? 2. What did Taiwanese college students think about some teachers’“testing to motivate effort”

mentality?

Method

To answer the first research question, a syllabi survey was conducted on the Internet. Many colleges in Taiwan require teachers to post their syllabi on their official website for public access, and the mandatory components usually include a clear grading scheme at the course level. All freshmen, according to the curriculum stipulated by the Ministry of Education, take required

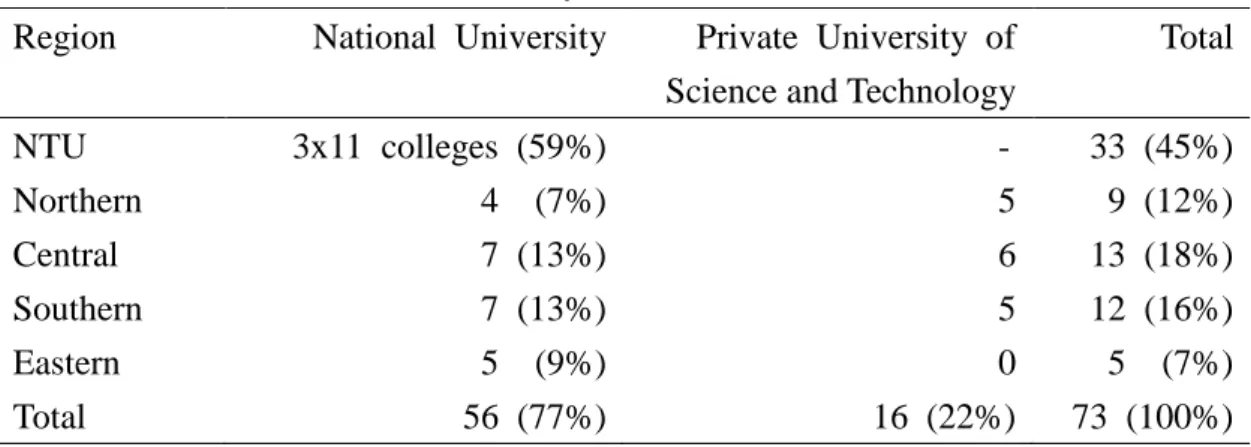

English skill courses. But the course title, content, and the exact number of credits vary among universities. Whether and how EFL courses are offered beyond the freshman year also depends on individual university’s foreign language learning policies. Therefore, the targeted syllabi of this survey were the first-year EFL skill-building courses, regardless of course titles. In order to ensure data representativeness, university ranking and geographical areas were considered. A stratified convenient sampling approach was used to cover public, higher-ranking and private vocational-track universities as well as those in the northern, central, southern, and eastern regions. Since the majority of universities do not have a comprehensive coverage of disciplines, the largest, in terms of student population, and highest ranking university in Taiwan with its eleven colleges were purposefully added into the syllabi profile. Some university websites require account number and passwords and therefore the access to syllabi was denied. Some syllabi did not include detailed grading information. In a few universities, syllabi were simply not available on the Internet. Eventually, 73 freshman-level, non-English major syllabi were collected for analysis. The distribution of these syllabi is shown in Table 1. In addition to the analysis of syllabi, 8 semi-structured teacher interviews were conducted as a follow-up to identify EFL teachers’rationale behind their grading policies.

Table 1. Sources and Distribution of Syllabi

Region National University Private University of Science and Technology

Total NTU 3x11 colleges (59%) - 33 (45%) Northern 4 (7%) 5 9 (12%) Central 7 (13%) 6 13 (18%) Southern 7 (13%) 5 12 (16%) Eastern 5 (9%) 0 5 (7%) Total 56 (77%) 16 (22%) 73 (100%)

The student data was part of a larger questionnaire collection. To obtain student opinions on the notion of “using tests to motivate effort”, a very brief dialogue was designed as a prompt, depicting the paradox of teachers’dilemma on whether to give more tests. Students might choose to agree with Teacher A (“Nowadays, if you don’t give tests, students won’t study.”), Teacher B (“But I am afraid that students may dislike English if I give tests often.”), Both, or Neither. Comments related to their choice were invited. The survey (Appendix 1) was presented to groups of college freshmen from 15 intact class groups in one university located at the northern part of Taiwan. The researcher explained the study to students and those who chose to take part in the study were given a correction tape as a reward.

Results and Discussion

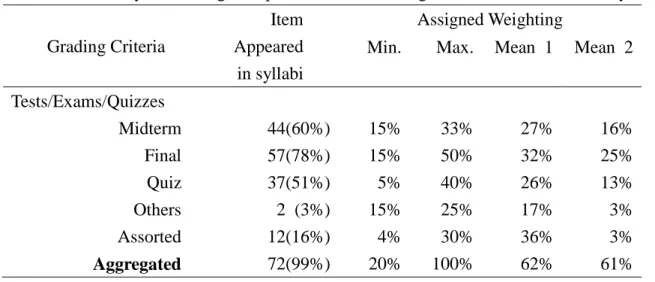

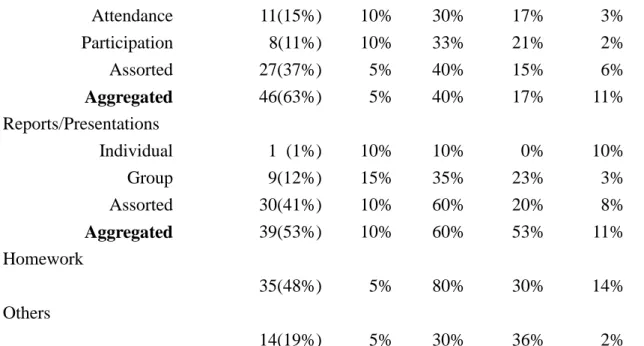

Most syllabi have a brief itemized grading scheme with specified grading items and their relative percentages. The categorization, however, varies from one syllabus to the other. Some

teacher put an assortment of items together and designated a combined percentage. For example, “quizzes and presentations and assignments”may account for 30% of total grade. Others had 60% for “tests”without providing further details like what kind of tests and how many there would be. But some taxonomy appeared to be more universal than others. After reviewing all the grading schemes, a summary of grading criteria and the relative percentages is presented in Table 2. For example, in the first row of the table, it is shown that 44 out of the 73 collected syllabi, i.e. 60%, included a midterm exam item. The assigned weighting of midterm exam ranged from 15% to 33%. The mean weighting of midterm exam among the 44 syllabi having a midterm was 27%, and the mean weighting when all syllabi were included, regardless of having a midterm or not, is 16%.

Four common categories were observed and, in the order of the most common to the least common, they are: tests/exams/quizzes, attendance and participation, oral/written reports and individual/group presentations, and homework. Among the 73 syllabi, only 1 did not include any test element. Tests, on average, accounted for 61% of student grading. Although in some syllabi various types of tests were combined as one category (“assorted”in the table), most teachers assigned clear percentages to different tests. Final exam was by far the most common item, appearing 78% of the time and accounting for 15% to 50% of total grades, followed by midterm and quiz, which also appeared 60% and 51% of the time respectively. Tests, when put together as one category, appeared 99% of the time on all the syllabi collected and the weighting ranged from 20% to 100%. The second most common item on the syllabi was attendance and participation. About two thirds of the teachers included this element in their syllabi with the weighting ranged from 5% to 40%. Attendance and participation as a combined category appeared 37% of the time, while attendance alone was shown 15% and participation alone 11%. On average, they

represented 11% to 17% of teachers’assigned grade. The third most common category was reports and presentations, shown in a little more than half of the syllabi with percentage

weighting ranging from 10% to 60%. Homework, the fourth type, was present 48% of the time and ranged from 5% to 80%. The last category, others, includes grading items such as dictation, attendance at the self-access learning center, watching sitcoms, and singing songs.

Table 2. Summary of Grading Components and Percentages from the 73 Collected Syllabi

Grading Criteria

Item Appeared in syllabi

Assigned Weighting

Min. Max. Mean 1 Mean 2

Tests/Exams/Quizzes Midterm 44(60%) 15% 33% 27% 16% Final 57(78%) 15% 50% 32% 25% Quiz 37(51%) 5% 40% 26% 13% Others 2 (3%) 15% 25% 17% 3% Assorted 12(16%) 4% 30% 36% 3% Aggregated 72(99%) 20% 100% 62% 61%

Attendance/Participation Attendance 11(15%) 10% 30% 17% 3% Participation 8(11%) 10% 33% 21% 2% Assorted 27(37%) 5% 40% 15% 6% Aggregated 46(63%) 5% 40% 17% 11% Reports/Presentations Individual 1 (1%) 10% 10% 0% 10% Group 9(12%) 15% 35% 23% 3% Assorted 30(41%) 10% 60% 20% 8% Aggregated 39(53%) 10% 60% 53% 11% Homework 35(48%) 5% 80% 30% 14% Others 14(19%) 5% 30% 36% 2%

Note: Mean 1 = the sum of percentage of all syllabi on this item / number of syllabi having this item; Mean 2 = the sum of percentage of all syllabi on this item / total number of syllabi, 73, regardless of having this particular item or not

Student Survey

On the student part, a total of 744 students were invited to participate and the distribution of student choices was summarized in Table 2. Percentages of students choosing to agree with Teacher A (giving tests to motivate effort), Teacher B (more cautious), Both, and Neither were 15%, 32%, 28%, and 13% respectively. Two percent did not make a decision and 10% chose not to participate. In addition to ticking off their choices, 289 students provided additional written responses to express their ideas. Their written responses were put together for analysis of

common themes. The results showed three major themes: student mentality on the “test/effort” relation, criteria for tests to successfully motivate student effort, and alternative methods

suggested to induce student effort.

Table 3. Number and Percentage of Student Opinions on the Survey

Groups #1 #2 #3 #4 No Choice Opting Out Comments Provided 1 8 21 21 3 0 2 7 2 11 22 18 5 3 0 14 3 10 24 10 14 0 0 34 4 4 9 13 4 0 0 5 5 9 22 17 6 0 0 23 6 5 27 16 10 1 0 16 7 8 10 9 5 2 17 14 8 6 12 9 6 5 20 16

9 13 13 18 8 0 3 24 10 10 18 14 3 1 5 30 11 3 6 19 3 0 0 7 12 8 10 6 4 2 0 13 13 7 13 14 11 0 9 40 14 5 14 19 6 0 10 16 15 4 19 5 9 0 8 30 Total 111 240 208 97 14 74 289 % 15% 32% 28% 13% 2% 10% 39% Mentality Types

The vast majority of students expressed a “no test, no study”and “will study if there is a test”attitude. Elaborations on this attitude provided by students can be further classified into three types. First, the attitude has to do with the competing time allocation within a student between studying for the EFL courses and other activities, including other course work, extracurricular activities, etc. The following quote illustrates a typical “test as a priority”time allocation perspective.

That was exactly me. When there is no test on this English course, I would spend my time on other courses that I would be tested on. As long as there is a test, I make sure I study for it. When there is no test for any subject, I would rather do things other than studying. (Teacher: H, Course: Listening; Student: #15)

Indeed, if there is no test, I lack the momentum to study. But if the frequency of tests is too high and preparing for this subject may take too much of my time, then I will consider shifting my study time to other courses. (Teacher: Ch, Course: Listening 2; Student: #13)

Secondly, students’high valuation on and pursuit for test scores urge them to work for tests. The numerical scores they get from tests are usually easy for them to interpret and compare

themselves against peers. Students seem to be highly vulnerable under the judgment of test results. They care very much about scores they get and would study for tests in order to get favorable scores. For example,

Preparing for tests is annoying, but getting high scores give me a pleasant sensation. (Teacher: H; Course: Listening; Student #3)

I want to learn English well. I don’t dislike it. I would also study it myself. But tests are like a two-sided sword; getting high scores gives me confidence, but doing poorly frustrates me (Usually I don’t do well.) (Teacher: H; Course: Listening; Student: #6)

Thirdly, many students attribute the high impact of test on their study effort to their own laziness and procrastination.

If there is no test, I may keep procrastinating and would not study, so I think we should have more tests but do not calculate the scores. (Teacher: W; Course: Reading 2; Student: #27)

References:

Adair-Hauck, B., Glisan, E. W., Koda, K., Swender, E. B., & Sandrock, P. (2006). The integrated performance assessment (IPA): Connecting assessment to instruction and learning. Foreign

Language Annals, 39(3), 359-382.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, September, 9-21.

Broekkamp, H., Van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M. (2007). Students’adaptation of study strategies when preparing for classroom tests. Educational Psychology Review, 19, 401-428.

Brookhart, S. M. (1991). Grading practices and validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and

practice, 10, 35-36.

Brookhart, S. M. (1994). Teachers’grading: Practice and theory. Applied Measurement in

Education, 7, 279-301.

Brookhart, S. M. (1997a). A theoretical framework for the role of classroom assessment in motivating student effort and achievement. Applied Measurement in Education, 10(2), 161-180.

Brookhart, S. M. (1997b). Effects of the classroom assessment environment on mathematics and science achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 90(6), 323-330.

Brookhart, S. M. (1998). Determinants of student effort on schoolwork and school-based achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 91(4), 201-208.

Brookhart, S. M. (2004). Classroom assessment: Tensions and interactions in theory and practice.

Teachers College Record, 106(3), 429-458.

Brookhart, S. M., & DeVoge, J. G. (1999). Testing a theory about the role of classroom assessment in student motivation and achievement. Applied Measurement in Education,

12(4), 409-425.

Brookhart, S. M., & Durkin, D. T. (2003). Classroom assessment, student motivation, and

achievement in high school social studies classes. Applied Measurement in Education, 16(1), 27-54.

Chappuis, S., & Stiggins, R. (2002). Classroom assessment for learning. Educational Leadership,

September, 40-43.

Chen, J. F., Warden, C. A., & Chang, H.-T. (2005). Motivators that do not motivate: The case of Chinese EFL learners and the influence of culture on motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 39(4), 609-633.

Cheng, H.-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1),

153-174.

Choi, I.-C. (2008). The impact of EFL testing on EFL education in Korea. Language Testing,

25(1), 39-62.

Colby-Kelly, C., & Turner, C. E. (2007). AFL research in the L2 classroom and evidence of usefulness: Taking formative assessment to the next level. The Canadian Modern Language

Review, 64(1), 9-38.

Connor-Greene, P. A. (2000). Assessing and promoting student learning: Blurring the line between teaching and testing. Teaching of Psychology, 27(2), 84-88.

Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom evaluation practices on students. Review of

Educational Research, 58(4), 438-481.

Cross, L. H., & Frary, R. B. (1999). Hodgepodge grading: Endorsed by students and teachers alike. Applied Measurement in Education, 12(1), 53-72.

Csizer, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The internal structure of language learning motivation and its relationship with language choice and learning effort. The Modern Language Journal, 89, 19-36.

Davison, C. (2007). Views from the chalkface: English language school-based assessment in Hong Kong. Language Assessment Quarterly, 4(1), 37-68.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001a). Teaching and researching motivation. Pearson Education Limited.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001b). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizer, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a nationwide longitudinal survey. Applied Linguistics, 23 (4), 421-462.

Fox, J. (2004). Biasing for the best in language testing and learning: An interview with Merrill Swain. Language Assessment Quarterly, 1(4), 235-251.

Guillotezux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL

Quarterly, 42(1), 55-77.

Harlen, W., & Crick, R. D. (2003). Testing and motivation for learning. Assessment in Education,

10(2), 169-207.

Harlen, W., & Winter, J. (2004). The development of assessment for learning: Learning from the case of science and mathematics. Language Testing, 21(3), 390-408.

Kouyoumdjian, H. (2004). Influence of unannounced quizzes and cumulative exam on attendance and study behavior. Teaching of Psychology, 31(2), 110-111.

Lamb, M. (2007). The impact of school on EFL learning motivation: An Indonesian case study.

TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 757-780.

Leung, C. (2004). Developing formative teacher assessment: Knowledge, practice, and change.

Language Assessment Quarterly, 1(1), 19-41.

Leung, C. (2007). Dynamic assessment: Assessment for and as Teaching? Language Assessment

Quarterly, 4(3), 257-278.

McMillan, J. H., Myran, S., & Workman, D. (2002). Elementary teachers’classroom assessment and grading practices. The Journal of Educational Research, 95(4), 203-213.

Natriello, G. (1987). The impact of evaluation processes on students. Educational Psychologist,

22(2), 155-175.

Olina, Z., & Sullivan, H. (2002). Effects of classroom evaluation strategies on student achievement and attitudes. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(3), 61-75.

Poehner, M. E. (2007). Beyond the test: L2 dynamic assessment and the transcendence of mediated learning. The Modern Language Journal, 91(3), 323-340.

Poehner, M.E., & Lantolf, J.P. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Language

Teaching Research, 9, 233-265.

Rea-Dickins, P., & Gardner, S. (2000). Snares and silver bullets: Disentangling the construct of formative assessment. Language Testing, 17(2), 215-243.

Remedios, R., Ritchie, K., & Lieberman, D. A. (2005). I used to like it but now I don’t: The effect of the transfer test in Northern Ireland on pupils’intrinsic motivation. British Journal of

Educational Psychology, 75, 435-452.

Ross, S. J. (2005). The impact of assessment method on foreign language proficiency growth.

Applied Linguistics, 26(3), 317-342.

Ruscio, J. (2001). Administering quizzes at random to increase students’reading. Teaching of

Psychology, 28(3), 204-206.

Shih, C.-M. (2008). The General English Proficiency Test. Language Assessment Quarterly, 5(1), 63-76.

Shohamy, E. (2001). The power of tests. London, England: Pearson Education Limited. Stiggins, R. J. (2002). Assessment crisis: The absence of assessment FOR learning. Phi Delta

Kappan, June, 758-765.

Torrance, H., & Pryor, J. (1998). Investigating formative assessment: Teaching, learning and

assessment in the classroom. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Van Etten, S., Freebern, G., & Pressley, M. (1997). College students’beliefs about exam preparation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22, 192-212.

Warden, C. A., Lin, H. J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting.

Foreign Language Annals, 33(5), 535-547.

Zhang, Z., & Burry-Stock, J. A. (2003). Classroom assessment practices and teachers’ self-perceived assessment skills. Applied Measurement in Education, 16(4), 323-342.

Appendix 1: Student Survey

Teacher A: Nowadays, if you don’t give tests, students won’t study.

Teacher B: But I am afraid that students may dislike English if I give tests often.

Which teacher do you agree with? Why?

計畫成果自評 本計畫最初規畫為兩年期,第一年對研究主題進行理論構念的澄清、第二年做實證研 究。獲得一年的補助後,將原本兩年的計畫稍作修改,以一年半的時間(經延長半年)完 成,將理論構念的部份以文獻分析方式討論,再輔以教師與學生兩部份的實證資料蒐集與 分析,預計於結案後共可產生三份論文以投稿期刊。 已產生的成果包含兩份我於交通大學英語教學研究所所指導、於九十七年七月完成的 碩士論文,題目分別是

1. 潘怡君 The relationship between college entrance exam and English learning motivation of senior high school students

2. 陳姿惠 Impacts of compulsory standardized examinations on college students’L2 learning motivation。

此外,在本計畫下已發表三篇國際研討會論文,分別是

1. Huang, S.-C. (2008). The educational aspect of formative assessments in L2 oral skill –a learner perspective. AILA 2008 –The 15th World Congress of Applied Linguistics. 第十五屆世界應用語言學會議,德國埃森,2008 年 8 月 24-29 日。 2. Chen, T.-H., & Huang, S.-C. (2007). Effects of compulsory standardized exams on

college students’L2 learning motivation. The 33rdJALT Annual Conference 日本全國 語學教育學會 2007 年年會,日本東京,2007 年 11 月 22-25 日。

3. Pan, Y.-C., & Huang, S.-C. (2007). College entrance exams and L2 learning motivation. The 33rd JALT Annual Conference 日本全國語學教育學會 2007 年年 會,日本東京,2007 年 11 月 22-25 日。

行政院國家科學委員會補助國內學者出席國際學術會議報告

97 年 9 月 15 日 報告人姓名 黃淑真 (科系所)服務校院 政治大學外文中心 時間 會議 地點 2008 年 8 月 24 日至 29 日 Essen, Germany 本會核定 補助文號 NSC96-2411-H004-047 會議 名稱 (中文) 第十五屆世界應用語言學會議 (英文) AILA 2008: The 15thWorld Congress of Applied Linguistics 發表

論文 題目

(中文) 英語口語學習形成性評量的教育層面 –學生觀點

(英文) The educational aspect of formative assessment in L2 oral skill – a learner perspective

報告內容應包括下列各項: 一、參加會議經過

AILA 是三年一度的國際性大型應用語言學研討會,上一次參與是在美國,此次於歐洲舉辦, 會期前後長達六天,論文發表場次眾多。我於八月二十一日出發前往德國,先於 Dusseldorf 稍 作停留,再轉火車前往會議所在地德國工業城 Essen。會場共分兩處,分別是市區會議中心 Congress Center Essen 及大學校區 University of Duisburg-Essen Campus,先熟悉會場與週 邊環境後,便準備被排訂在八月二十五日週一上午於 Essen 大學校園的論文發表。發表當天同一 場地與會者與前後發表者均對測驗相關議題有共同的研究興趣,彼此的詰問與意見交流十分熱 烈,我的論文是首度嘗試將動機研究與測驗做結合,想法有所突破,但經由聽眾的質疑讓我對立 論的切入點有更深刻的思考,也在回國後重新參考文獻,做了大幅的修正,應是此次發表最大的 收穫。論文發表過後,便參與了多場 keynote speeches 及 paper sessions,此次研討會較有 特色之處是捨棄了獨尊美國的觀點,許多論文從歐洲、非洲、甚至世界多語系的角度出發,雖然 與個人的研究沒有直接的相關,但視野的開啟是為之前多次參與在美國的研討會所不曾有的經 驗。會外非正式的交流中,亦有機會與新加坡、香港、大陸等地的學者交換意見,談及各自校園 的工作環境與挑戰,十分有趣。 二、與會心得 此次參與會議聆聽多場論文發表後,得到不少啟發,最大的體悟是本領域的論文發表,因其 社會人文與應用的性質,與硬科學(hard science)有相當的不同,不少資深學者著墨在論點的 切入、研究問題意義的闡揚,使一個原本看似平凡的研究問題,其重要性能經由論述突顯,而這 正是我過去多年來所欠缺的。在過去的學術訓練中,我往往只將焦點放在研究方法上,將自己的 聲音縮到最小,侷限自己在研究產業的最下游,貢獻自然也有限,分析結果一旦整理出來,似乎 論文也近完成,未能就其意義與文獻進行深入的對話。如今發現,資料分析完成後,其後續的思 考、思辯、以及完整精確的書寫以將思辯的過程表達,其重要性一點也不亞於研究過程。要能做 到目前心中的理想境界,惟有透過大量的文獻閱讀及閱讀時的質疑與思考,才能進而成功的鋪排 論點,寫出思考有力的論文。 三、考察參觀活動(無是項活動者省略) 無 四、建議 未來在國內舉辦學術研討會時,在地化的特色應是地主國應強調的學術重點,藉由舉辦權突 顯在地研究應是我們舉行學術活動時的責任之一。 五、攜回資料名稱及內容

1. Conference Program –Multilingualism: Challenges and Opprtunities

2. Riagain, D. O. (2006). Voces Diversae: Lesser-Used Language Education in Europe. Belfast Studies in Language, Culture and Politics.

六、其他 無