infection control and hospital epidemiology march 2007, vol. 28, no. 3

c o n c i s e c o m m u n i c a t i o n

Challenges Faced by Hospital

Healthcare Workers in Using

a Syndrome-Based Surveillance System

During the 2003 Outbreak of Severe

Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Taiwan

Fuh-Yuan Shih, MD; Muh-Yong Yen, MD;Jiunn-Shyan Wu, MS; Fang-Kuei Chang, BS; Lih-Wen Lin, BS; Mei-Shang Ho, MD; Chao A. Hsiung, PhD; Ih-Jen Su, MD; Melissa A. Marx, DrPH; Howard Sobel, MD; Chwan-Chuen King, DrPH

Because the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Taiwan in 2003 was worsened by hospital infections, we analyzed 229 questionnaires (84.8% of 270 sent) completed by surveyed healthcare workers who cared for patients with SARS in 3 types of hospitals, to identify surveillance problems. Atypical clinical pre-sentation was the most often reported problem, regardless of hospital type, which strongly indicates that more timely syndromic surveil-lance was needed.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28:354-357

The rapid detection of infectious disease during hospital visits is vital to minimizing health threats during outbreaks.1-3

Be-fore March 2003, when the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Taiwan began, all passive systems of re-porting infectious disease were based on physician diagnosis of “known” diseases. During the SARS outbreak, 2 reporting systems were used. One was Taiwan’s Clinical Syndrome Sur-veillance (CSS), which was used to monitor clinical symptoms of hemorrhagic, neurological, respiratory, jaundice, and di-arrhea syndromes and to help healthcare workers (HCWs) investigate unknown infectious diseases with unclear clinical presentations. It was piloted in June 2000 and had previously been used to assist in difficult diagnoses.4The other was the

National Notifiable Disease Surveillance (NNDS) system, which, starting on April 17, 2003, required clinicians to report both suspected and probable cases of SARS.5-11

By June 30, 2003, of the 3,349 cases reported to NNDS, 360 were clinically probable SARS cases later proven by detection of SARS coronavirus, of which 288 (80%) were associated with hospitals, primarily after mid-April.8-10This SARS outbreak had

a significant impact on healthcare systems and tested the sur-veillance of emerging infectious disease in Taiwan.5Although

HCWs were required to do everything possible to help reduce the spread of contagion,11 their over-reporting overwhelmed

the public healthcare surveillance system.8We surveyed HCWs

who cared for patients with SARS in 3 different types of hos-pitals, to evaluate the accessibility and acceptability of the CSS and NNDS systems and to identify hindrances to reporting.

m e t h o d s

Hospitals in Taiwan are accredited at 3 levels—medical center, regional hospital, and community hospital—on the basis of their comprehensiveness of medical services and their size. Taiwan’s 20 medical centers reported 1,379 cases of SARS, the 71 regional hospitals reported 1,395 cases, and the 128 community hospitals reported 524 cases. In fact, 83 of 86 healthcare facilities (17 medical centers, 39 regional hospitals, and 27 community hospitals) cared for patients with con-firmed SARS coronavirus infection. In total, 54 of the 83 facilities were sampled, which were chosen on the basis of those with the highest numbers of SARS cases reported and to include the 42 hospitals that had hospital-associated con-firmed cases of SARS coronavirus infection. Under the guid-ance of the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Preven-tion (Taiwan CDC), the infecPreven-tion control coordinators of these 54 hospitals were sent self-administered, structured, anonymous questionnaires in September 2003. Private prac-titioners were excluded because they rarely tended patients with SARS. Each infection control coordinator disseminated the questionnaire to the primary care physicians, clinical nurses, infection control personnel, hospital administrators, and ancillary medical support personnel who cared for the patients with SARS. The completed questionnaires were mailed back by the same coordinators. Those who did not respond were sent the questionnaire again. In total, 6 (35%) of the 17 medical centers, 32 (82%) of the 39 regional hos-pitals, and 16 (59%) of the 27 community hospitals with confirmed SARS cases submitted acceptably completed ques-tionnaires. The questionnaire collected the following infor-mation: (1) HCW data (extra infectious control training and/ or orientation received, professional background, and work experience); (2) 30 types of problems in reporting, the extent of the problems, and reasons that the HCWs might overlook a probable SARS case or delay reporting one; and (3) sub-jective opinions about the usefulness of the NNDS and CSS reporting systems, on a scale from 0, indicating least useful, to 10, indicating most useful.

All questionnaire items had been formulated jointly with the surveillance personnel at Taiwan CDC. Content validity was verified by a panel of experts composed of infectious diseases physicians, nurses, and epidemiologists. It was fur-ther tested by small groups of HCWs outside the selected hospitals, to ensure that the content and wording were un-derstandable and reliable before the questionnaire was ad-ministered. Quantitative data were summarized and tested for statistical significance by use of the x2test for proportional

data; the x2test for trend, to compare the reasons for missing

cases or delayed reporting in different types of hospitals; and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank sum test, for com-paring the usefulness and acceptance of the NNDS and CSS systems.

recommendations for syndrome-based surveillance of sars 355

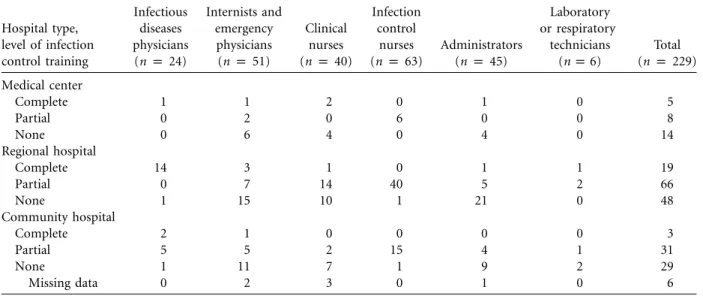

table 1. Professional Characteristics of the 229 Healthcare Workers Who Participated in the Study Hospital type, level of infection control training Infectious diseases physicians (n p 24) Internists and emergency physicians (n p 51) Clinical nurses (n p 40) Infection control nurses (n p 63) Administrators (n p 45) Laboratory or respiratory technicians (n p 6) Total (n p 229) Medical center Complete 1 1 2 0 1 0 5 Partial 0 2 0 6 0 0 8 None 0 6 4 0 4 0 14 Regional hospital Complete 14 3 1 0 1 1 19 Partial 0 7 14 40 5 2 66 None 1 15 10 1 21 0 48 Community hospital Complete 2 1 0 0 0 0 3 Partial 5 5 2 15 4 1 31 None 1 11 7 1 9 2 29 Missing data 0 2 3 0 1 0 6

table 2. Problems Experienced by 229 Healthcare Workers in Reporting Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), According to Type of Hospital

Problem

No. of responses, by type of hospital Medical

center

Regional hospital

Community

hospital All hospitals

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No

Patient had atypical clinical presentation 15 12 95 41 44 22 154 75

Need to wait for laboratory results or clinical responses 12 15 67 69 32 34 111 118 Desire to protect benefits and/or privacy of patients and their families 12 15 62 74 35 31 109 120 Need to seek consultation from infection professionalsa 6 21 54 82 37 29 97 132 Intentional bias toward over-reporting because of fear of being punished

if the case is missed 16 11 41 95 25 41 82 147

Influence of public media 5 22 50 86 24 42 79 150

Labor-intensive and time-consuming nature of reporting process 12 15 37 99 21 45 70 159 Too-frequent changes in case definition of SARS 6 21 38 98 19 47 63 166

Too many reporting channels to report to 11 16 32 104 17 49 60 169

Concerns about possible panic of other patients in the hospital 3 24 40 96 16 50 59 170

a P!.05in x2test for trend.

re s u l t s

The overall response rate was 86.3% (233 of 270 question-naries sent were completed). In addition, 229 questionnaires (84.8%) were completed well enough to include in our anal-ysis. These 229 completed questionnaires comprised 27 (90%) of 30 questionnaires sent to medical centers, 136 (85%) of 160 sent to regional hospitals, and 66 (82.5%) of 80 sent to community hospitals, with no statistically significant differ-ence in response rate. Of the 229 questionnaires, 24 (10%) went to infectious diseases physicians, 51 (22%) went to in-ternists and emergency physicians, 63 (28%) went to infection control nurses, 40 (17%) went to clinical nurses, 45 (20%) went to hospital administrators, and 6 (3%) went to labo-ratory or respilabo-ratory technicians. The infection control train-ing of the respondents is shown in Table 1.

According to questionnaire responses, medical center

work-ers were more hindered from reporting SARS cases by internal administrative control mechanisms (such as screening them first through a SARS review committee) than were non–med-ical center workers (59% vs 33%;P p .009). HCWs at com-munity hospitals, compared with HCWs at regional hospitals and HCWs at medical centers, were more often hindered in reporting SARS cases by having to wait for treatment response (45% vs 32% and 22%;P p .02), by pressure from patients or their families (36% vs 22% and 15%; P p .012), and by inconsistent laboratory results and diagnoses (17% vs 7% and 0%; P p .004).

On the basis of individual responses, the most frequently reported problems were atypical clinical presentations (69% of respondents), having to wait for laboratory or clinical re-sponses (49%), protecting the privacy of patients (48%), and seeking consultation (44%) (Table 2). Administrators and

356 infection control and hospital epidemiology march 2007, vol. 28, no. 3

internists or emergency physicians were more often delayed by internal administrative controls than were nurses (43% vs 29%;P p .04); and nurses were more often delayed by having to wait for laboratory results (57% vs 41%;P p .02). Primary care and infectious diseases physicians were more apprehen-sive about reporting than were nurses (43% vs 29%; P p ). Infectious diseases physicians were least influenced by .048

fear of media attention. Physicians and nurses without in-fectious diseases training waited for consultation before re-porting SARS cases more often than did those with training (45% vs 15%;P p .003). HCWs found the NNDS system to be better and less burdensome than the CSS system (z p ; , by Wilcoxon matched-pairs test), although 2.73 P p .006

they rated both systems to be very useful.

d i s c u s s i o n

One important impact of the SARS outbreak was the initi-ation and acceleriniti-ation of improvement in the performance of Taiwan’s hospital surveillance systems for emerging infec-tious diseases.2,3Not ignoring possible recall bias and selection

bias, we found that the syndrome-based surveillance system in Taiwan could be improved by educating workers about the use of a broader case definition, the protection of confiden-tiality, the creation of a professional consultation system, the maintenance of a cooperative relationship between public healthcare agencies and healthcare facilities, and the simpli-fication of reporting.

Atypical clinical presentation of SARS was the first re-porting problem. Because HCWs generally lacked an under-standing of syndromic surveillance, the waiting time for lab-oratory results or clinical responses affected reporting of cases (by 48% of respondents), even when the clinical criteria were fulfilled. This barrier to reporting can be addressed by ed-ucating HCWs about the public healthcare goal of surveil-lance and how to use broader case definitions in syndromic surveillance and by changing the goal of different surveillance systems at a policy level. The CSS system should serve dif-ferent goals than the NNDS system by focusing on early detection rather than 100% accuracy.

To avoid the second reporting problem—possible stigma-tization of patients with SARS12-14

—healthcare policy should be made to ensure optimal care and confidentiality of the patients, and HCWs need to learn how to maintain confi-dentiality. Lack of a professional consultation system was the third problem. Reporting was affected at community hospitals and clinics because they were less prepared and more strongly influenced by the public media. In May 2003, Taiwan CDC established designated SARS contract laboratories and an in-terhospital infection control mutual aid network to provide better technological support.

Fines or suspension of licenses for delayed or under-re-porting caused 36% of the HCWs to intentionally over-re-port, resulting in a misallocation of limited resources. With less than 1% of reporting being motivated by finances, a

cooperative rather than an adversarial relationship between public health agencies and healthcare facilities is needed. Fi-nally, problems with an overburden of paperwork and many people to report can be improved by modern medical in-formatics, along with standardized terminology and integra-tion of different data sets to increase efficiency.15-20

In the future, in considering the threat of other emerging infectious diseases—for example, avian influenza—and pos-sible administrative delays in reporting, healthcare authorities might want to obtain electronically automated, integratable relevant data sets in a timely manner from sentinel hospitals or to directly tap electronic medical records to identify tem-poral and geographic distributions of symptoms that can serve as early warning signals.19,20

acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the help from uncountable public healthcare pro-fessionals at Taiwan CDC and local healthcare bureaus.

This study was financially supported by Taiwan CDC grant DOH92-DC-SA03 and National Science Council grant NSC92-2751-B-002-020-Y.

From the College of Public Health, National Taiwan University (F.-Y.S., C.-C.K.), the Department of Emergency Medicine, National Taiwan Uni-versity Hospital (F.-Y.S.), the Taipei City Hospital (M.-Y.Y.), the National Yang-Ming University (M.-Y.Y.), the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (J.-S.W., F.-K.C., L.-W.L., I.-J.S.), the Institute of Biomedical Sci-ences, Academia Sinica (M.-S.H.), and the Division of Biostatistics and Bioin-formatics, National Health Research Institute (C.A.H.), Taipei, Taiwan; the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia (M.A.M.), and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York, New York (M.A.M.); and the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (H.S.).

Address reprint requests to Chwan-Chuen King, DrPH, Institute of Epi-demiology, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, No. 17, Xu Zhou Rd., Taipei City, Taiwan 100, Republic of China (cc_king99@hotmail .com).

Received July 3, 2005; accepted March 10, 2006; electronically published February 13, 2007.

䉷 2007 by The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. All rights reserved. 0899-823X/2007/2803-0017$15.00. DOI: 10.1086/508835

re f e re n c e s

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the guidelines working group. MMWR 2001; 50(RR-13):1-35. 2. Jones J, Terndrup TE, Franz DR, Eitzen EM. Future challenges in

pre-paring for and responding to bioterrorism events. Emerg Med Clin North

Am 2002; 20:501-524.

3. Thacker SB, Stroup DF. Future directions for comprehensive public health surveillance and health information system in the United States.

Am J Epidemiol 1994; 140:383-397.

4. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The current infec-tious diseases surveillance systems in Taiwan. Available at: http://www.cdc .gov.tw/En/dsi/ShowPublication.ASP?RecNop588. Accessed November 21, 2003.

5. Twu SJ, Chen TJ, Chen CJ, et al. Control measures for severe acute re-spiratory syndrome (SARS) in Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:718-720. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary clinical

de-scription of severe acute respiratory syndrome. MMWR Morb Mortal

recommendations for syndrome-based surveillance of sars 357

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and coronavirus testing—United States, 2003. MMWR

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:297-302.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe acute respiratory syndrome—Taiwan. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:461-466. 9. Chen YC, Chen PJ, Chang SC, et al. Infection control and SARS trans-mission among healthworkers, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:895-898. 10. Chen YC, Huang LM, Chang CC, et al. SARS in hospital emergency

room. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:782-788.

11. Hsieh YH, King CC, Chen CW, et al. Quarantine for SARS, Taiwan.

Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:278-282.

12. Bayer R, Colgrove J. Public health vs. civil liberties. Science 2002; 297:1811. 13. Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Managing SARS amidst uncertainty. N Engl J

Med 2003; 348:1947-1948.

14. Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hos-pital. CMAJ 2003; 168:1245-1251.

15. Bedard Y, Henriques WD. Modern information technologies in

envi-ronmental health surveillance: an overview and analysis. Can J Pub

Health 2002; 93(Suppl 1):S29-S33.

16. Barthell EN, Cordell WH, Moorhead JC, et al. The Frontlines of Medicine Project: a proposal for the standardized communication of emergency department data for public health uses including syndromic surveillance for biological and chemical terrorism. Ann Emerg Med 2002; 39:422-429. 17. Irvin CB, Nouban PP, Rice K. Syndromic analysis of computerized emer-gency department patients’ chief complaints: an opportunity for bio-terrorism and influenza surveillance. Ann Emerg Med 2003; 41:447-452. 18. Begier EM, Sockwell D, Branch LM, et al. The national capitol region’s emergency department syndromic surveillance system: do chief com-plaint and discharge diagnosis yield different results? Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:393-396.

19. Wagner MM, Robinson JM, Tsui F-C, Espino JU, Hogan WR. Design of a national retail data monitor for public health surveillance. J Am

Med Inform Assoc 2003; 10:409-418.

20. Tsui FC, Espino JU, Dato VM, Gesteland PH, Hutman J, Wagner MM. Technical description of RODS: a real-time public health surveillance system. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003; 10:399-408.