http://fla.sagepub.com/

First Language

http://fla.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/10/14/0142723711422631 The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0142723711422631

published online 18 October 2011

First Language

Ya-Hui Luo, Catherine E. Snow and Chien-Ju Chang

Taiwanese families

Mother-child talk during joint book reading in low-income American and

- Oct 25, 2012 version of this article was published on

more recent A

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: First Language

Additional services and information for

http://fla.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts: http://fla.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions: What is This? - Oct 18, 2011 OnlineFirst Version of Record

>>

- Oct 25, 2012 Version of Record

First Language 1 –18 © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: sagepub.

co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0142723711422631 fla.sagepub.com

FIRST

LANGUAGE

Mother–child talk during

joint book reading in

low-income American

and Taiwanese families

Ya-Hui Luo

National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Catherine E. Snow

Harvard Graduate School of Education, USA

Chien-Ju Chang

National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Abstract

This study compares interactions during joint book reading of 14 Taiwanese and 15 American mother–child pairs from low-income families. All mother–child pairs read the same book, ‘The very hungry caterpillar’, at home and their interactions were recorded. Taiwanese and American mothers demonstrated both similarities and differences during joint book reading. Taiwanese mothers talked more, gave and requested more information, but requested and received fewer evaluations from their children. These cross-cultural differences reveal that joint book reading is not just for entertainment; instead, it is a means for transmission of moral values and proper conduct as well as for the socialization of appropriate parent–child conversation styles in the Taiwanese and American families studied.

Keywords

cross-cultural comparison, joint book reading, low-income families

Corresponding author:

Chien-Ju Chang, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, National Taiwan Normal University, 162, Ho-Ping East Road, Section 1, Taipei 106, Taiwan

Email: changch2@ntnu.edu.tw

Introduction

Joint book reading is widely studied both as a means of promoting children’s early literacy development (Bus, van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995; Cochran-Smith, 1984; Kang, Kim, & Pan, 2009; Nikolajeva, 2003; Senechal & LeFevre, 2001; Senechal, Thomas, & Monker, 1995; Snow & Dickinson, 1990; Strickland & Taylor, 1989; Sulzby & Teale, 1991) and as a form of parent–child interaction (Chang & Lin, 2006; DeTemple, 2001; Heath, 1982, 1983; Melzi & Caspe, 2005; Murase, Dale, Ogura, Yamashita, & Mahieu, 2005). Initially, the utilization of joint book reading was explored mostly in White, middle-class, North American families. Nevertheless, in recent decades, studies on joint book reading have been conducted in China, Israel, Japan, Korea, Peru, and Taiwan (Chan, Brandone, & Tardif, 2009; Chang & Lin, 2006; Choi, 2000; Melzi & Caspe, 2005; Murase et al., 2005; Ninio, 1980; Tardif, 1996; Tardif, Gelman, & Xu, 1999; Tardif, Shatz, & Nigles, 1997). These studies have found that mothers and children from different countries show distinc-tive book reading interactions which reflect both properties of the language being used and culturally prescribed forms of communication.

Cross-cultural studies on joint book reading

Culture has been shown to influence various aspects of mother–child interactions during book reading (Melzi & Caspe, 2005; Murase et al., 2005). Murase and his colleagues (2005) reported that Japanese mothers responded to children’s labeling with interpersonal utter-ances more than American mothers, while American mothers responded with elaborative information requests more than Japanese mothers. Melzi and Caspe (2005) studied Peruvian and American mothers sharing a wordless picture book with their three-year-olds. American mothers privileged the story-building style, which encourages children’s participation and consisted of mostly non-immediate talk. In contrast, Peruvian mothers favored the story-telling style, which featured a high proportion of immediate talk using descriptions of the book and tag questions.

Both cultural and linguistic features can affect the use of nouns and verbs in parent–child conversations. Chinese mothers produced more main verbs and fewer common nouns than did American mothers when reading books with their 20-month-olds (Chan et al., 2009; Tardif, 1996; Tardif et al., 1997, 1999). Similarly, 20-month-old Mandarin-speaking children did not show noun bias and they produced more verbs during parent–child conversations than did American children. Possible explanations for the relative verb preference among Chinese children included the higher frequency of verbs in maternal input, the prominent sentence position of verbs, and the morphological simplicity of Mandarin verbs (Tardif, 1996), as well as higher imageability ratings (Ma, Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, McDonough, & Tardif, 2009). Verb preferences were also found in Korean mothers’ speech during book reading and toy-play contexts (Choi, 2000), and in Japanese mothers (Ogura, Dale, Yamashita, Murase, & Mahieu, 2006). Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cultures were all influenced by the Confucian ideology. All are classified as ‘collective’ societies and they exhibit similar styles of visual perception (Chan et al., 2009). Research on scene perception has shown that, when shown the same set of naturalistic scenes and tested on attention given to different parts of those scenes, people of individualistic societies concentrate on

the focal agent (i.e. a person or an object), but people of collectivistic societies attend more to the things around the focal agent and the relationship between the focal agent and its context. Thus, it is not surprising that Chinese, Korean, and Japanese mothers’ use of nouns and verbs during joint book reading would show similar patterns, and be different from the pattern of culturally individualist, American mothers. All these studies suggest the importance of cultural influences on parent–child book reading interactions.

The cross-cultural studies of joint book-reading leave many open questions. First, they focused only on maternal input and/or interaction styles (Chan et al., 2009; Choi, 2000; Melzi & Caspe, 2005), without examining children’s talk. Second, these studies have focused only on limited aspects of mother–child interactions during joint book reading, such as the usage of nouns and verbs (Chan et al., 2009; Choi, 2000; Ogura et al., 2006; Tardif, 1996; Tardif et al., 1997, 1999) and the maternal utterances preceding or following child-produced labels (Murase et al., 2005). Other potentially revealing aspects of joint book reading, such as the purposes and the content of mothers’ and children’s talk, were not examined.

Parent–child interactions in Taiwanese and American

families

Parent–child interactions in Taiwanese families are governed by the hierarchical relation-ships defined by the Confucian ideology (Chao, 1994, Fung, Miller, & Lin, 2004; Miller, Wiley, Fung, & Liang, 1997). According to the Confucian principles, children have to show loyalty and respect to their elders, especially to their parents. Parents have the primary responsibility of teaching, guiding, and disciplining their children from a very young age. Children are constantly exposed to explicit models or examples of proper conduct (Chao, 1994; Miller, Sandel, Liang, & Fung, 2008). Parents remind children of their transgressions repeatedly in family narratives to provide moral lessons; ‘opportunity education’ (Fung et al., 2004) is used whenever appropriate since Taiwanese parents believe that teaching moral values with concrete examples works better than teaching them in the abstract (Fung et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008). In accordance with Confucian principles, Taiwanese children are trained to speak little and to listen actively (Fung et al., 2004). Elaborative narratives from children are generally discouraged. The conversational environment in most Chinese families is characterized by talk that is repetitive, didactic, and low in elabo-ration (Wang, Leichtman, & Davies, 2000). Mandarin-Chinese-speaking mothers also use tag questions frequently when they speak to young children (Erbaugh, 1992), to actively support the learning of new words and new information, as well as to prepare children for teacher–student interactions, in which child obedience leads to teacher-approval.

In contrast to Chinese/Taiwanese parents’ focus on didactic teaching during parent–child interactions, European-American parents care more about fostering their children’s self-confidence and self-esteem through personal storytelling (Miller et al., 1997) and family narratives (Fung et al., 2004; Miller, Fung, & Mintz, 1996). European American parents generally emphasize individuality, independence, and self-expression as the socialization values and goals for their children (Chao, 1994; Fung et al., 2004). Parents hope their children will develop a ‘sense of self’ (Chao, 1995) and they believe that they should help their children to develop the ability to express their feelings and emotions clearly so that their needs can be met by others (Chao, 1995). While narrating personal stories with their children,

European-American mothers use high-elaborative memory conversations and provide abun-dant support and evaluative feedback to foster children’s participation in constructing personal stories (Fivush & Wang, 2005; Minami & McCabe, 1995; Wang et al., 2000).

The cross-cultural studies reviewed above all interpret joint book reading as a guided cultural activity in which values, norms, regulations, communication style, pragmatics, and preferences of a cultural group may be transmitted through the interactions between parents and children (Rogoff, 1990). Parents implement, consciously or unconsciously, culturally appropriate parent–child conversation styles during joint book reading time. Parents also utilize book reading time to transmit culturally valued norms and moral lessons to children. As a result, joint book reading between Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs is a prime context for examining the influences of culture on the practices of joint book reading. In this study, we investigate the similarities and differences in Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs’ interactions during joint book reading to respond to two gaps in the literature. First, understanding how cultural values and culturally specific parent–child conversation styles are revealed during these book-reading interactions can contribute to our understanding of variations in children’s language development and the socialization of appropriate communication styles in different cultures. Second, past cross-cultural com-parisons of parent–child interactions in Chinese and American families were mostly focused on either the usage of nouns and verbs during book reading or on parent–child conversations during narration of personal stories and/or family events. No study has compared the practices of joint book reading more comprehensively, including the purposes and content of talk, during parent–child conversations, in Taiwanese and American families.

We investigated how Taiwanese and American mothers interact with their children during joint reading of the same picture book. The specific research questions guiding our study were: (1) What are the linguistic characteristics (number of utterances, mean length of utter-ance (MLU), and mean length of turn (MLT) of Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs during joint book reading? (2) How do Taiwanese and American mothers differ in the purposes of their talk during joint book reading? (3) How do Taiwanese and American mothers differ in the content of their talk during joint book reading? (4) How do Taiwanese and American children differ in the purposes and content of talk during joint book reading? Based on the literature review, we predicted that Taiwanese mothers would talk more during joint book reading, give more information to their children, and show a greater use of teach-ing behaviors, tag questions, and moral/conduct education. We also predicted that American mothers would encourage their children to participate more actively in the book reading.

Method

This study utilized data collected by two research projects, both focused on joint book reading in low-income families. The US data were collected starting in 1987 as part of the Harvard Home-School Study of Language and Literacy Development (HSLLD). These data are available publicly on the website of the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) (www.childes.com). The Taiwan data were collected via the third author’s National Science Council (NSC) research project (Chang, 2005). The Taiwan NSC project modeled its data collection and data analysis procedures on those used by the HSLLD project, in order to facilitate cross-cultural comparisons.

Participants

The participants of the Taiwan NSC project were 15 mothers and their three year-old children. Among the 15 children, seven were boys and eight were girls. The average age of the children was three years and six months (range = 3;2 to 3;11). All families were recruited with the help of public kindergartens in Taipei. Mothers and children spoke Mandarin Chinese as their primary language at home. Most mothers had nine years to 12 years of formal education, except one mother who held a bachelor’s degree. Only one mother read to her children daily; the frequency of joint book reading in the other families ranged from weekly or biweekly to rarely. Most of the children in this study owned fewer than 25 books. After preliminary data analyses, one Taiwanese mother-daughter pair identified as an extreme outlier was dropped from the study; this mother had a higher level of education than the other Taiwanese mothers and produced a much greater number of utterances than any other mother.

Fifteen mother–child pairs were selected from the HSLLD participants who engaged in joint book reading during the first home visit, when participating children were three years old. Since the HSLLD project had a larger pool of participants, the 15 children in the HSLLD project whose age in days was closest to the 15 children in the Taiwan NSC project were selected (gender was matched as well). Among the 15 children, there were seven boys and eight girls. The average age of the children was three years and seven months old (range was 3;4 to 3;11). Mothers and children spoke English as their primary language at home. Based on information obtained from the yearly interview conducted with participating mothers (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001), 96% of mothers in the HSLLD project reported having experi-ence reading storybooks to their children at home; however, only 66% of mothers read to their children daily. Sixty-two percent of mothers reported having more than 25 children’s book at home and 38% of participating families had less than 25 children’s book at home.

The participants in the HSLLD project and the NSC project were similar in several ways. First, they were all from low-income families (as classified by the local government standard). Second, the mothers had similar educational level; most of them did not have a high school diploma or were high school graduates without post-high school education. Third, they both lived in big cities. Boston is the largest city in Massachusetts, whereas Taipei is the capital city of Taiwan.

Procedures

Data were collected at the home of mother–child pairs in both projects (Chang, 2005; Dickinson & Tabors, 2001). Collecting data at participants’ homes was designed to promote participants’ ease and optimize naturalness of the interactions. The same procedures were used during data collection for the HSLLD project and the NSC project. Each mother–child pair was asked to read the book The very hungry caterpillar (Carle, 1969) together. This book has been used widely in joint book reading studies done in other countries, optimizing the opportunities for cross-cultural comparison. The Mandarin Chinese translation of the book is as literal as possible, with the same relation of content to pictures as the English version. Both Taiwanese and American mothers were instructed to read the book in the manner typically used while reading with their children. Experimenters were present while

mothers and their children read the book together, but did not interfere in the interaction. For NSC project, both audio-taping and video-taping were used to record the joint book reading interactions between each mother–child pair. However, only audio-taping of mother– child interactions was used for the HSLLD project.

Transcription and coding system

The audio-taped and/or video-taped data were transcribed according to the standard CHAT format of the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) (MacWhinney, 2000), allowing later data analyses by both the CLAN and the SPSS programs.

Coding system. All transcripts were coded by the researchers using the coding system adapted

from the original coding system of the HSLLD study. The coding unit was the clause. Talk was coded in two ways: purposes and content. All examples of coding presented here were taken from the actual mother–child conversations.

Purposes of talk. The purpose of talk was divided into on-task talk and off-task talk.

On-task talk was further divided into four categories: request for information, provision of information, provision of feedback, and interactional strategies. Talk not included in on-task talk was categorized as off-task talk. On-Task talk included:

1. Requests for information: Interlocutors ask questions related to items pictured in the book or topics elaborated from the contents of the book.

2. Provision of information: Interlocutors give information related to items pictured in the book or topics elaborated from the contents of the book. Provision of information was further subcategorized into spontaneous and responsive information provision. Sometimes mothers answered questions they themselves had asked if their children failed to respond.

3. Provision of feedback: Interlocutors give feedback to new information or answers to the other interlocutor’s questions.

4. Interactional strategies: Strategies used to invite, encourage, maintain, and modify interlocutors’ attention and participation during joint book reading. These strategies included the following: (1) Request for attention: e.g. Look at all the holes; (2) Request for clarification: e.g. A what? (3) Request for evaluation: e.g., He got real big eating all that stuff huh? (4) Provision of attention: e.g., Hmm; (5) Provision of clarification: e.g., See he ate the green leaf? And he felt better. His belly felt better; (6) Provision of evaluation: e.g., This is a great book! (7) Confirmation: e.g., He’s not a butterfly no more? (8) Tag question: e.g., There are two plums here, aren’t there? (Confirmatory); The little caterpillar ate a lot of things and became very fat, didn’t he? (Evaluative)

Content of talk. Content of information requested and/or provided was divided into two

categories: immediate talk and non-immediate talk. Immediate talk focuses on the story, the pictures shown in the book, or on things that could be seen readily in the surrounding environment. Immediate talk included: (1) Location: e.g., Where is the little egg? (2) Event/ Action: e.g., What is the caterpillar doing? (3) Label: e.g., What is this? (4) Attributes:

Identifying the color, the size, or the number of objects. e.g., How many oranges are here? Non-immediate talk included: (1) Inference: e.g., Why the caterpillar had a stomachache? (2) Printed-related: Pointing out printed words e.g., On Monday, he ate one apple but he was still hungry (pointing to the words on the book while the mother reads). (3) Text-Reader Connection: e.g., Ice cream. It is your favorite, right? (4) Vocabulary and Language: e.g., The warm sun came up. What does the word ‘warm’ mean? (5) Opportunity Education: Teaching and guiding children to acquire appropriate moral values, everyday norms and regulations, and culturally valued norms and regulations whenever appropriate (see results section on p. 10-11 for more explanation of opportunity education).

Inter-rater reliability

Transcripts of the joint book reading interactions produced by the 15 pairs of Taiwanese and American participants were coded by the first author. Twenty percent of transcripts in both the Taiwan and the US studies were randomly selected for coding by another coder (a gradu-ate student for the Taiwan NSC project and a bilingual researcher for the US HSLLD project). Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa for all codes in the three Taiwan NSC transcripts and the three US HSLLD transcripts. The inter-rater reliability for the Taiwan NSC project was 0.91 (95% confidence level: 0.871 ~ 0.946). The inter-rater reliability for the US HSLLD project was 0.94 (95% confidence level: 0.883 ~ 0.997).

Data analysis

Transcripts of parent–child interactions during joint book reading were first analyzed using the CLAN program of the CHILDES system. Mean length of utterance (MLU) and type token ratio (TTR) of both mothers and children in the HSLLD project and the NSC project were calculated. Independent t-tests were further conducted to compare the Taiwanese mother–child pairs to the American mother–child pairs.

Results

Linguistic characteristics

Taiwanese mothers produced significantly more utterances, word types, and word tokens than their American counterparts did when reading The very hungry caterpillar with their children (see Table 1). In contrast, American mothers produced significantly higher mean lengths of utterance (MLU) than did Taiwanese mothers. There was no significant differ-ence in mean length of turn (MLT) of these two groups.

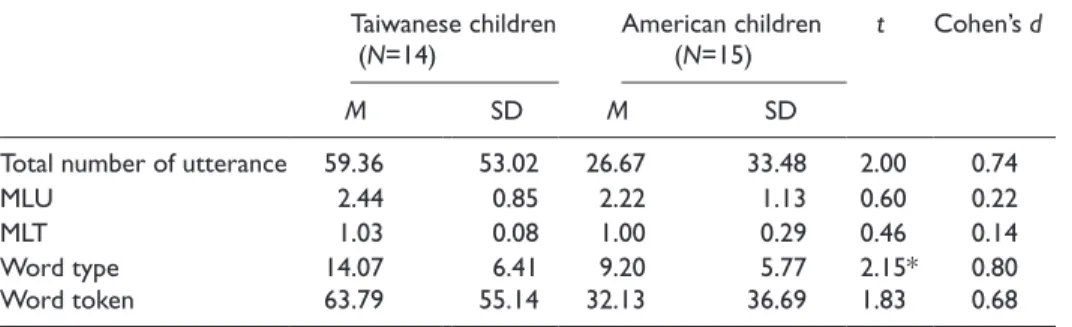

Like their mothers, Taiwanese children produced more utterances than their American counterparts (see Table 2). In addition, Taiwanese children produced significantly more word types, though not significantly more word tokens than did the American children. Taiwanese children in this study used a richer variety of words than did American children.

Comparing the results shown in Table 1, Table 2, and in the above paragraph, it is clear that both Taiwanese and American mothers produced about twice as many utterances as their children did during a joint book reading session. Both Taiwanese and American mothers produced more than two utterances per turn while their children produced only

a single utterance per turn during the conversations. Because of the differences in the number of words and of utterances produced by Taiwanese and American mothers, the subsequent comparison of mothers’ usage of interactional strategies was conducted by using the percentage of each interactional strategy out of the total number of reading strate-gies used during joint book reading interactions.

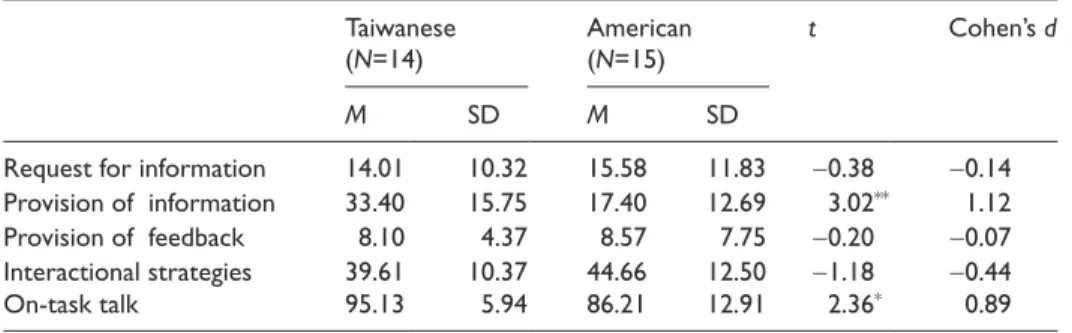

Purposes of mothers’ talk

Only on-task talk of Taiwanese and American mothers was compared; off-task talk was not analyzed in this study. The means and standard deviations of the percentages of the four categories of the purposes of mothers’ on-task talk are shown in Table 3.

Taiwanese mothers produced a significantly higher percentage of on-task talk and of giving information than did American mothers. Taiwanese mothers stayed on-task more and they talked less about things unrelated to the story with their children during joint book reading.

Table 1. Comparison of Taiwanese and American mothers’ mean length of utterance (MLU),

mean length of turns (MLT), total number of word type (Word type), and total number of word token (Word token)

Taiwanese mothers

(N=14) American mothers (N=15) t Cohen’s d

M SD M SD

Total number of utterances 117.86 59.63 60.13 34.59 3.22** 1.18

MLU 5.37 1.21 6.93 1.74 -2.83** -1.04

MLT 2.60 0.95 2.80 1.42 -0.46 -0.17 Word types 25.14 8.72 16.07 5.91 3.30** 1.22

Word tokens 137.86 70.68 49.87 39.57 4.18** 1.54

**p < .01.

Table 2. Comparison of Taiwanese and American children’s mean length of utterance (MLU),

mean length of turns (MLT), total number of word types (Word type), and total number of words (Word token)

Taiwanese children

(N=14) American children (N=15) t Cohen’s d

M SD M SD

Total number of utterance 59.36 53.02 26.67 33.48 2.00 0.74 MLU 2.44 0.85 2.22 1.13 0.60 0.22 MLT 1.03 0.08 1.00 0.29 0.46 0.14 Word type 14.07 6.41 9.20 5.77 2.15* 0.80 Word token 63.79 55.14 32.13 36.69 1.83 0.68

Taiwanese mothers produced a significantly higher percentage of evaluations than American mothers did (see Table 4). In contrast, American mothers requested a signifi-cantly higher percentage of evaluations from their children than their Taiwanese counter-parts did. Also, the mean proportion of confirmations used by Taiwanese mothers was found to be significantly higher than that used by American mothers. It is also interesting to note that Taiwanese mothers used significantly more tag questions for confirmation than their American counterparts, who did not used tag questions at all.

Content of mothers’ talk

Both Taiwanese and American mothers engaged in a substantially higher percentage of immediate talk than non-immediate talk. Taiwanese mothers gave a significantly higher percentage of spontaneous immediate information (M=26.02) to their children than did American mothers (M=11.90, t(29)=2.76, p<.05). In addition, Taiwanese mothers responded more to questions asked by themselves while American mothers responded Table 3. Comparison of purposes of Taiwanese and American mothers’ talk

Taiwanese

(N=14) American (N=15) t Cohen’s d

M SD M SD

Request for information 14.01 10.32 15.58 11.83 -0.38 -0.14 Provision of information 33.40 15.75 17.40 12.69 3.02** 1.12

Provision of feedback 8.10 4.37 8.57 7.75 -0.20 -0.07 Interactional strategies 39.61 10.37 44.66 12.50 -1.18 -0.44 On-task talk 95.13 5.94 86.21 12.91 2.36* 0.89

*p<.05; **p<.01

Table 4. Comparison of interactional strategies used by Taiwanese and American mothers

Taiwanese

(N=14) American (N=15) t Cohen’s d

M SD M SD

Total confirmation 7.59 4.81 4.18 4.98 3.16** 0.70

Confirmation: tag question 7.31 4.70 0 - 5.82** 2.24

Confirmation: non-tag 0.28 0.51 4.18 4.98 -3.02** -1.10

Provision of attention 4.46 4.30 4.45 4.90 0.01 0.00 Provision of clarification 0.23 0.43 0.16 0.42 0.46 0.16 Provision of evaluation 9.06 3.95 5.41 4.20 2.41* 0.90

Request for attention 9.87 5.89 14.06 6.65 -1.79 -0.68 Request for clarification 0.80 0.86 0.35 0.81 1.48 0.54 Request for evaluation 0.63 0.56 3.92 4.58 -2.76* -1.01

more to questions asked by their children; however, neither of these differences reached significance.

There was no significant difference found in frequency or incidence of Taiwanese and American mothers’ requests for information during joint book reading. However, both Taiwanese and American mothers requested a substantially higher percentage of labeling responses from their children than any other kind of response. Questions about the attributes of objects (such as colors, shapes, and numbers) were frequently requested by both groups of mothers as well.

Table 5 shows the comparison of different types of spontaneous immediate information mothers gave to their children during joint book reading time. Both Taiwanese and American mothers gave primarily labeling and event/action-related information to their children while reading books with them. Nevertheless, Taiwanese mothers produced an overwhelmingly higher percentage of labeling and event/action-related questions than their American coun-terparts did.

Taiwanese mothers produced higher percentages of non-immediate information con-cerning text-reader connection and inferences, whereas American mothers gave higher percentages of information concerning vocabulary and language usage. However, the only Table 5. Comparison of spontaneous immediate information given by Taiwanese and American

mothers Taiwanese (N=14) American (N=15) t Cohen’s d M SD M SD Location 0.95 0.94 0.50 1.04 1.24 0.45 Attribute 2.13 2.50 1.67 4.01 0.36 0.14 Label 12.83 15.38 3.72 2.99 2.18* 0.82 Event/action 9.15 4.71 2.70 2.85 4.49** 1.66 *p<.05; **p<.01.

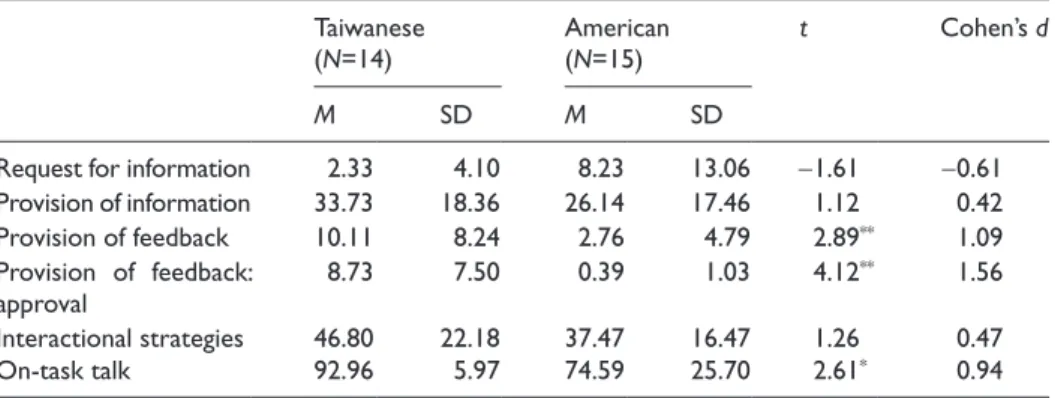

Table 6. Comparison of purposes of Taiwanese and American children’s talk

Taiwanese

(N=14) American (N=15) t Cohen’s d

M SD M SD

Request for information 2.33 4.10 8.23 13.06 -1.61 -0.61 Provision of information 33.73 18.36 26.14 17.46 1.12 0.42 Provision of feedback 10.11 8.24 2.76 4.79 2.89** 1.09 Provision of feedback: approval 8.73 7.50 0.39 1.03 4.12 ** 1.56 Interactional strategies 46.80 22.18 37.47 16.47 1.26 0.47 On-task talk 92.96 5.97 74.59 25.70 2.61* 0.94

significant cross-cultural difference found was print-related information -- pointing to and reading the words one-by-one in the book. Taiwanese mothers gave a significantly higher percentage of print-related information (M=0.23) than their American counterparts did (M=0, t(29)=2.64, p<.05).

Moreover, opportunity education was used six times by four Taiwanese mothers during these book-reading sessions. Though the frequency was too low for statistical testing, there were no occurrences of opportunity education in the American transcripts. Although both Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs read about caterpillar’s consumption of large amount and great varieties of food items (including certain junk foods such as candies, desserts, and ice creams), only Taiwanese mothers utilized caterpillar’s eating behavior as the jumping-off point for discussing the importance of balanced nutrition or good eating habits. None of American mothers launched a similar discussion with their children. The nutritional discussion was one example of how opportunity education was employed by Taiwanese mothers. Additional topics targeted for opportunity education included the importance of politeness and mothers’ expectations for their children. (see the following excerpts):

Excerpts: Opportunity education used by Taiwanese mothers 1. Importance of Politeness

Mother: The teacher lent this book to us. Please return it to the teacher. Mother: And you need to say ‘Thank you, teacher!’

2. Mother’s Expectation of Child

Mother: To become smart and beautiful when you grow up, you need to eat vegetables. Child: OK.

Mother: But in addition to become smart and beautiful, what else shall you be? Mother: You shall be a kind person too, shall you?

Mother: Then mommy will be very satisfied. 3. Good Eating Habits

Mother: Why (the caterpillar had a stomach ache)? Child: Yeah.

Mother: He didn’t have a good eating habit, didn’t he? Child: Yes.

Mother: He ate too much. That’s not a good eating habit. Child: Yeah.

Mother: Can you eat a lot of junk foods at once? Child: No.

Purposes and content of children’s talk

As shown in Table 6, Taiwanese children gave a significantly higher percentage of feed-back and approving feedfeed-back to their mothers than did American children. Furthermore, Taiwanese children stayed on-task significantly more during joint book reading than did American children.

The comparison of the use of interactional strategies by Taiwanese and American children during joint book reading showed that Taiwanese children produced a significantly higher percentage of clarifications (M=1.23, SD=1.68) than did American children (M=0.05, SD=0.19, t(29)=2.60, p<.05). Out of nine clarifications given by Taiwanese children, six immediately followed mothers’ requests for clarification. There were no significant differences between the groups in the types of information produced by children.

American children tended to request labels more than Taiwanese children, but this trend was not significant. Like their mothers, American and Taiwanese children mostly produced labels and event/action-related information. Although Taiwanese children’s ratio of event/ action-related to labeling information mimicked their mothers’, the difference in the child talk was not significant.

Discussion

The comparison of Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs’ talk while they read ‘The

very hungry caterpillar’ together has revealed some similarities as well as differences in

purposes and content of talk. In both cultures, joint book reading is typically led by mothers/ parents and it is commonly used as a means to provide information and knowledge to chil-dren. Mothers talked much more than their three-year-olds, and they posed an array of questions and gave considerable information to their children while reading with them. In contrast, Kang and colleagues (2009) reported that low-income five-years-olds reading

‘The very hungry caterpillar’ talked as much as their mothers did, suggesting that as

chil-dren’s language skills improve they can contribute more to these conversations.

Taiwanese and American mothers both utilized more immediate talk than non-immediate talk during conversation with their children. Both groups of mothers talked most about the names, colors, and numbers of the food items the caterpillar ate and the actions the caterpil-lar performed. Taiwanese mothers produced about 26% immediate talk and less than 4% non-immediate talk compared to 11.9% immediate and 2.17% non-immediate talk produced by American mothers. The focus on immediate talk by both Taiwanese and American mothers suggests that both groups of mothers were utilizing joint book reading as a context to teach their children names, colors, and numbers, and to concentrate in this first reading of the book on the actions and events central to the story (Chang, 2005; Chang & Lin, 2006; Dickinson & Tabors, 2001). This supports Tare and her colleagues’ findings (Tare, Shatz, & Gilbertson, 2008) on mothers’ utilization of child-directed speech to help children learn non-object concepts such as colors and numbers.

Several interesting cross-cultural differences were identified after comparing Taiwanese and American mother–child interactions during joint book reading. First, we replicated the differences in use of nouns and verbs found in the studies by Tardif (1996) and Tardif and her colleagues (1997, 1999), namely that: Mandarin-speaking mothers produced more main verbs and fewer common nouns than English-speaking mothers during joint book reading. This cultural difference remained prominent after removing all behavioral control talk by mothers and all talk that was irrelevant to picture book reading (Chan et al., 2009). Although we did not code nouns and verbs as Tardif and her colleagues did, we used two relevant information content codes: labeling of objects vs. events/actions performed by the characters

in the book. All the clauses coded as giving labeling information had common nouns in them. Similarly all the clauses coded as giving event/action-related information had main verbs in them. Both Taiwanese and American mothers labeled objects more than actions and event. However, Taiwanese mothers produced a significantly higher proportion of event- and action-related information and also requested more event/action-related infor-mation from their children than did American mothers. This phenomenon was explained by Chan and her colleagues (2009) as the influence of Chinese’ and Americans’ preferred style in speech and perception, the language properties of Mandarin and English, and the type of scene depicted in the picture book. Our comparison of Taiwanese and American mothers’ talk during joint book reading validates the general finding first reported by Tardif (1996) and Tardif and her colleagues (1997, 1999), and it is also congruent with results found in the studies by Choi (2000) and Ogura and her colleagues (2006) on Korean and Japanese respectively.

Opportunity education is a strategy that was used solely by the Taiwanese mothers in this cross-cultural comparison study. Opportunity education was highlighted by Fung et al. (2004) as a unique method used by Taiwanese parents to teach moral lessons in her cross-cultural comparison of transgression narratives in Taiwanese and American families. In Chinese culture, being a parent requires constant instruction and supervision of one’s child so that the child may develop into a useful person who glorifies the whole family. Chinese parents believe that moral lessons preached using concrete examples and role models are more efficient than teaching the importance of moral values abstractly (Fung et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008).

Chinese parents also believe strongly in the importance of their role as the teachers of their children, so during joint book reading parents would focus on transmitting knowledge, skill, and information to the child enthusiastically (Chao, 1994; Zhou, 2002). Congruent to our prediction, Taiwanese mothers in this study have shown the tendency of enthusiasti-cally teaching their children about names, colors, and numbers of objects seen in the picture book as well as the events and actions performed by the caterpillar. Taiwanese mothers asked their children numerous questions, including some questions their children could not answer; thus they had to answer some of their own questions. The number of self-produced questions Taiwanese mothers answered was almost twice that of American moth-ers. Similarly, the Taiwanese tendency to teach was reflected in the significantly higher percentage of evaluations, and the significantly higher percentage of on-task talk produced by Taiwanese mothers during joint book reading. Taiwanese mothers also pointed to the words in the text while reading to their children as a way to teach their children to recognize the printed Chinese characters. In contrast, American mothers were not observed using opportunity education while reading The very hungry caterpillar with their children. This might be the result of American mothers generally viewing joint book reading as a means to foster enjoyment of reading (Senechal & LeFevre, 2001).

Tag questions are another special technique these Taiwanese mothers used frequently while reading with their children, and high SES Taiwanese mothers have also been reported to use them frequently (C.-J. Huang, 2003). In contrast, American mothers did not use tag questions during book reading with their children. In this study, tag questions were utilized by Taiwanese mothers for confirmation of statements given by mothers and for children to respond to moth-ers’ evaluative statements. Children’s reply to evaluative questions could either be approval

or rejection of mothers’ evaluation. However, whether Taiwanese mothers used evaluative or confirmatory tag questions, the expected answers from Taiwanese children were always giving approval to mothers’ statements. Examples of usage of tag questions were as follows:

Mother: The egg is here, isn’t it? (Confirmatory)

Mother: The butterfly is very beautiful, isn’t it? (Evaluative)

Taiwanese mothers’ use of tag questions fits Erbaugh’s description of ‘the quiz style of conversation’ employed by Mandarin-speaking mothers when speaking to young children (1992, p. 400). This style of conversation is characterized by an adult who asks a child a question to which the adult has a preselected answer in mind. Usually the adult models the correct answer in the tag question, as the examples above show. Furthermore, the adult would expect the child to agree with the preselected answer modeled in the tag question. Erbaugh (1992) has argued that, regardless of social classes, parents in Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, and American Chinatown all show a similar tendency of using this quiz style of conversation when talking to young children. Parents use this style to socialize young children into the conversation style found between teachers and pupils in classrooms at all levels in the above countries, where teachers value students’ obedience, choral response, and good memorization ability.

Furthermore, this study found that American mothers requested significantly more evaluations from their children than Taiwanese mothers did. Interestingly, in a study com-paring Canadian and Japanese mothers’ talk during stories of past experiences with their children, Canadian mothers were found to request more evaluation from their children than did Japanese mothers (Minami & McCabe, 1995). Both American and Canadian parents evidently wish to encourage and promote children’s self-expression during parent–child interactions. Many American parents consider helping their children to foster a ‘sense of self’ as a vital goal and they also hope their children will have the ability to be autonomous, assertive, and able to express their own ideas and feelings clearly (Chao, 1995; Wang et al., 2000). By requesting more evaluations from their children, the American mothers in this study have created more chances for their children to participate during joint book reading, a finding congruent with our prediction.

Comparison of Taiwanese and American children’s talk and interactions with their mothers during joint book reading revealed a few significant cross-cultural differences such as Taiwanese children’s significantly greater provision of clarifications and approving feedback to their mothers as compared to American children. Taiwanese children’s use of approving feedback was related to the tag questions asked by and the evaluations given by their mothers. Out of 71 approving feedback responses produced by Taiwanese children, 29 immediately followed mothers’ confirmatory and evaluative tag questions and 10 of them followed mothers’ evaluative comments. These findings are congruent with previous studies arguing that Taiwanese children are socialized to be obedient and to show respect to their elders according to the Confucian ideology (Chao, 1994; Erbaugh, 1992; Zhou, 2002). Taiwanese children approved most of their mothers’ statements during mother–child conversations and they gave clarifications whenever their mothers asked for them. On the contrary, American children in this study did not show such a high rate of approving parents’ statements during parent–child conversations. This finding suggests that in American families, parents and children have a relatively more equal status, and parents generally encourage children to express their own opinions (Chao, 1995; Fung et al., 2004).

Comparison of Taiwanese and American children’s talk and interactions with their mothers during joint book reading also revealed a few nonsignificant differences worthy of being followed up with a larger sample. This study shows that perhaps three-year-olds were starting to mirror their mothers’ preference in noun and verb usage during joint book reading. Taiwanese children gave a nonsignificantly higher percentage of event/action-related information to their mothers than did American children. Similarly, American children requested a nonsignificantly higher percentage of noun-related information from their mothers. The differential usage of nouns and verbs in Taiwanese and American children might be the influences of the Mandarin Chinese being a tenseless language (C.-C. Huang, 2003). As a tenseless language, Mandarin Chinese does not prescribe verb changes to indicate tense; hence, it might be easier for Taiwanese children to learn the proper usage of verbs compared to that of American children, who have to grasp the concept of regular as well as irregular verbs and the various past tense forms. Another possible explanation is that, as was found in this study, Taiwanese mothers use a higher frequency of verbs during mother–child conversations; Taiwanese children have higher exposure to verbs than did American children, and thus learn to use verbs in a way that mirrors the maternal usage of verbs and nouns. Given the limited power of this study, it would be valuable to follow up these results with a larger sample of participants or with older children to support this finding.

Summing up the findings of this study, Taiwanese mothers’ use of both opportunity education and tag questions as well as American mothers’ frequent request of evaluation from their children have both demonstrated parents’ utilization of joint book reading as a context for the socialization of appropriate parent–child and teacher–student interaction styles and for the transmission of moral values and proper conducts to their children. A simple task such as reading a storybook to your children might not be as simple as it looks. Indeed, joint book reading is frequently laden with cultural values and is often employed by parents from different cultures as a tool for socialization. In addition, the three-year-old Taiwanese and American children in this study have started to mirror their mothers’ pattern of nouns and verbs usage during joint book reading conversations. That Taiwanese children produce a significantly higher rate of approval to mothers’ claims sug-gests that they have started to show the culturally appropriate parent–child conversation style to which their parents have socialized them. Hence, joint book reading is an excellent context to observe and track children’s language development as well as to compare cross-cultural differences in language development and language socialization.

Several limitations, however, should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the sample size of this study is quite small, limiting our power to find evidence of small differences. In addition, the participants in this study were only a sample of low income families living in the Taipei area and the Boston area. Even though strong effect sizes were found for all the significant cultural differences between Taiwanese and American mother–child conversations, the generalizability of the findings to all Taiwanese and American low-income families is limited. Further studies including larger groups of Taiwanese and American families from other areas are recommended.

This study focused only on the similarities and differences between Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs’ information requesting, information giving, and interac-tional strategies used during joint book reading. Possible cross-cultural differences in

vocabulary usage, sentence structures, and maternal corrective feedback were not covered in this study. These topics could be considered in further investigations of cross-cultural differences between Taiwanese and American mother–child pairs’ conversation during joint book reading.

Funding

This work was supported by National Science Council [grant numbers 93-2413-H-152-010, 97-2628-H-003-001-MY3, and 99-2811-H-003-005] and the Aim for the Top University grant from Ministry of Education, Taiwan, R.O.C.

References

Bus, A. G., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Pellegrini, A. D. (1995). Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of

Educational Research, 65(1), 1–21.

Carle, E. (1969). The very hungry caterpillar. New York, NY: Philomel Books.

Chan, C. C. Y., Brandone, A. C., & Tardif, T. (2009). Culture, context, or behavioral control: English- and Mandarin-speaking mothers’ use of nouns and verbs in joint book reading. Journal

of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(4), 584–602.

Chang, C. (2005). Home support for language and literacy development in preschoolers. (NSC 93-2413-H-152-010). Taipei: National Science Council.

Chang, C., & Lin, J. (2006). Mother–child book-reading interactions in low-income families.

Journal of National Taiwan Normal University: Education, 5(1), 185–212.

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65(4), 1111–1119. Chao, R. K. (1995). Chinese and European American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers’

childrearing beliefs. Ethos, 23(3), 328–354.

Choi, S. (2000). Caregiver input in English and Korean: Use of nouns and verbs in book-reading and toy-play contexts. Journal of Child Language, 27, 69–96.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1984). The making of a reader. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

DeTemple, J. M. (2001). Parents and Children reading books together. In D. K. Dickinson & P. O. Tabors (Eds.), Beginning literacy with language (pp. 31–51). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Dickinson, D. K., & Tabors, P. O. (2001). Beginning literacy with language. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Erbaugh, M. S. (1992). The acquisition of Mandarin. In D. I. Slobin (Ed.), The crosslinguistic study

of language acquisition (Vol. 3, pp. 373–455). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fivush, R., & Wang, Q. (2005). Emotion talk in mother–child conversations of the shared past: The effects of culture, gender, and event valence. Journal of Cognition and Development, 6(4), 489–506. Fung, H., Miller, P. J., & Lin, L. C. (2004). Listening is active: Lessons from the narrative practices

of Taiwanese families. In M. W. Pratt & B. E. Fiese (Eds.), Family stories and the life course:

Across time and generations (pp. 303–323). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Heath, S. B. (1982). What no bedtime story means: Narrative skills at home and school. Language

in Society, 11(1), 49–76.

Huang, C.-C. (2003). Mandarin temporality inference in child, maternal and adult speech. First

Language, 23, 147–169.

Huang, C.-J. (2003). Styles of mother–child book reading interaction in different social classes. Unpublished Master’s thesis. National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Kang, J. Y., Kim, Y.-S., & Pan, B. A. (2009). Five-year-olds’ book talk and story retelling: Contributions of mother–child joint bookreading. First Language, 29, 243–265.

Ma, W., Golinkoff, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., McDonough, C., & Tardif, T. (2009). Imageability predicts the age of acquisition of verbs in Chinese children. Journal of Child Language, 36(2), 405–423. MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES Project: Tools for analyzing talk. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Melzi, G., & Caspe, M. (2005). Variation in maternal narrative styles during book reading interactions.

Narrative Inquiry, 15(1), 101–125.

Miller, P. J., Fung, H., & Mintz, J. (1996). Self-construction through narrative practices: A Chinese and American comparison of early socialization. Ethos, 24(2), 237–280.

Miller, P. J., Sandel, T. L., Liang, C., & Fung, H. (2008). Narrating transgressions in U.S. and Taiwan. In R. A. LeVine & R. S. New (Eds.), Anthropology and child development: A

cross-cultural reader (pp. 198–212). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Miller, P. J., Wiley, A., Fung, H., & Liang, C. H. (1997). Personal storytelling as a medium of socialization in Chinese and American families. Child Development, 68(3), 557–568. Minami, M., & McCabe, A. (1995). Rice balls and bear hunts: Japanese and North American family

narrative patterns. Journal of Child Language, 22, 423–445.

Murase, T., Dale, P. S., Ogura, T., Yamashita, Y., & Mahieu, A. (2005). Mother–child conversation during joint book reading in Japan and the USA. First Language, 25(2), 197–218.

Nikolajeva, M. (2003). Verbal and visual literacy: The role of picture books in the reading experience of young children. In N. Hall, J. Larson, & J. Marsh (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood literacy (pp. 235–248). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ninio, A. (1980). Picture book reading in mother–infant dyads belonging to two subgroups in Israel.

Child Development, 51, 587–590.

Ogura, T., Dale, P. S., Yamashita, Y., Murase, T., & Mahieu, A. (2006). The use of nouns and verbs by Japanese children and their caregivers in book-reading and toy-playing contexts. Journal of

Child Language, 33, 1–29.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Senechal, M., & LeFevre, J. (2001). Storybook reading and parent teaching: Links to language and literacy development. In P. R. Britto & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), The role of family literacy

environments in promoting young children’s emerging literacy skills (New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development No.92, pp. 39–52). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Senechal, M., Thomas, E., & Monker, J. (1995). Individual differences in 4-year-old children’s acqui-sition of vocabulary during storybook reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 218–229. Snow, C. E., & Dickinson, D. K. (1990). Social sources of narrative skills at home and at school.

First Language, 10, 87–103.

Strickland, D. S., & Taylor, D. (1989). Family storybook reading: Implications for children, families, and curriculum. In D. Strickland & L. Morrow (Eds.), Emerging literacy: Young children learn

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. (1991). Emergent literacy. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2, pp. 727–758.). New York: Longman. Tardif, T. (1996). Nouns are not always learned before verbs: Evidence from Mandarin speakers’

early vocabularies. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 492–504.

Tardif, T., Gelman, S. A., & Xu, F. (1999). Putting the ‘nouns bias’ in context: A comparison of English and Mandarin. Child Development, 70(3), 620–635.

Tardif, T., Shatz, M., & Nigles, L. (1997). Caregiver speech and children’s use of nouns and verbs: A comparison of English, Italian, and Mandarin. Journal of Child Language, 24, 535–565. Tare, M., Shatz, M., & Gilbertson, L. (2008). Maternal uses of non-object terms in child-directed

speech: Color, number and time. First Language, 28, 87–100.

Wang, Q., Leichtman, M. D., & Davies, K. I. (2000). Sharing memories and telling stories: American and Chinese mothers and their 3-year-olds. Memory, 7, 149–177.

Zhou, J. (2002). Pragmatic development of Mandarin-speaking children from 14 months to 32 months. Nanjing, China: Nanjing Normal University Press.