Occupational stress in nurses in psychiatric institutions in Taiwan

全文

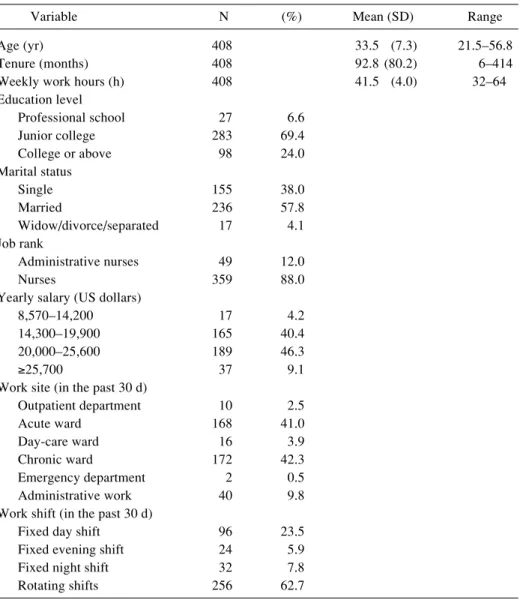

(2) Hsiu-Chuan SHEN, et al.: Stress in Psychiatry Nurses. other hospital workers8, 9, 11). Epidemiological studies utilizing the JCQ have been broadly consistent with Karasek’s hypothesis, showing associations of high levels of job strain with increasing risks of various health problems, including job strain and burnout 9) , psychosomatic symptoms 10) , and poor health 11) . Incorporation of a third dimension, work-related social support added to the power of the model because studies have consistently shown that the deleterious effects of job strain were greater for those with lower levels of social support at work10, 12, 13). The JCQ was previously translated into Chinese, and consists of items for assessment of job control, psychological demands, supervisor support, and coworker support14). The model was shown to be valid and reliable when used among Taiwanese workers. To determine the effects of job content and assault on stress and well-being of psychiatric nurses, this investigation studied a representative sample of nurses among public psychiatric institutions in Taiwan for their psychological demands, job control, and social support at work, as well as potential hazards.. Subjects Nurses from all public psychiatric institutions owned by the State of Taiwan and governed by the Ministry of Health were included in the study population. These five institutions were visited in October to December, 2001, and administrators of the nursing department were invited to participate in this study after careful explanation of the study protocol.. Methods This cross-sectional study utilized a questionnaire to obtain information about the health care worker’s job content and psychological stress. The study protocol was approved by the Institution Review Board at National Cheng Kung University Medical College, and complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki15). A total of 573 nurses were working at the five institutions as of January 1st, 2002. They were included as the study subjects of this investigation. The questionnaires were disseminated by section leaders and collected within one week. The purpose and contents of the questionnaire were explained to the subjects before their voluntary participation. Job stressors and other work environment Chinese versions of two questionnaires were used: the “Job Content Questionnaire” (C-JCQ) 14) ; and the International Quality of Life Assessment Short Form-36 (IQOLA SF-36)16). The C-JCQ includes questions on skill discretion, decision authority, psychological demands, supervisor support and coworker support. In addition, work environment and safety were also inquired, especially on attack or harassment events. Attacks were. 219. categorized into non-sexual attacks (severity: non-violent, violent and life-threatening) and sexual harassment (verbal harassment and physical harassment) according to Rosenberg et al. 17) and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS)3). Perceived occupational stress The extent of perceived occupational stress was assessed by the self-reported response to the question “How often have you felt very stressed at work in the past one month?” Those nurses who answered “almost always” or “often” were grouped as having “high” perceived occupational stress, and those who answered “sometimes”, “infrequently”, or “almost never” were grouped as having “low” perceived occupational stress18). Outcome variables The SF-36 was translated and validated by a joint committee of Taiwanese researchers and has been used in various studies in Taiwan with good validity and reproducibility19, 20). The authors obtained authorization for its use from the committee. Statistical analysis Statistical packages SAS and JMP were used for the analysis. Multivariate linear regression and multivariate logistic regression were used to determine statistical significance. The significance level was set at 0.05. In logistic regression, the difference between the loglikelihood from the fitted model and the log-likelihood that uses horizontal lines is a test statistic to examine the hypothesis that the factor variable has no effect on the response. The ratio of this test statistic to the background log-likelihood is subtracted from 1 to calculate R2. Job control, psychological demands, and workplace support were classified into two levels (high and low) using the national survey mean as cut-off points. Nurses were further categorized into High strain (low control and high demand), Low strain (high control and low demand), Active (high control and high demand), and Passive (low control and low demand) groups.. Results Among the 573 nurses, 544 returned the completed questionnaire. After excluding male nurses (12), parttime nurses (75), those who had worked in the current institution for less than 6 months (23), and incomplete responses to the questions (26), 408 were included in the final analysis. The demographic information is shown in Table 1. Among these 408 nurses, the average age was 33.5 ± 7.3 (standard deviation, SD) years, tenure 92.8 ± 80.2 months, weekly working hours 41.5 ± 4.0 h. The results of C-JCQ scores are shown in Table 2. Job control, psychological demands, and workplace support averaged 66.9 (7.7), 32.9 (4.6), and 23.7 (3.3). Data of.

(3) 220. J Occup Health, Vol. 47, 2005. Table 1. Demographic characteristics and work conditions of the study population Variable. N. Age (yr) Tenure (months) Weekly work hours (h) Education level Professional school Junior college College or above Marital status Single Married Widow/divorce/separated Job rank Administrative nurses Nurses Yearly salary (US dollars) 8,570–14,200 14,300–19,900 20,000–25,600 ≥25,700 Work site (in the past 30 d) Outpatient department Acute ward Day-care ward Chronic ward Emergency department Administrative work Work shift (in the past 30 d) Fixed day shift Fixed evening shift Fixed night shift Rotating shifts. (%). 408 408 408 27 283 98. 6.6 69.4 24.0. 155 236 17. 38.0 57.8 4.1. 49 359. 12.0 88.0. 17 165 189 37. 4.2 40.4 46.3 9.1. 10 168 16 172 2 40. 2.5 41.0 3.9 42.3 0.5 9.8. 96 24 32 256. 23.5 5.9 7.8 62.7. Mean (SD). Range. 33.5 (7.3) 92.8 (80.2) 41.5 (4.0). 21.5–56.8 6–414 32–64. Table 2. Mean values (standard deviations), and ranges (possible minimum and maximum) of C-JCQ sub-scales JCO sub-scale (# of items). This study. Women (No.) Job control (9) Skill discretion (6) Decision authority (3) Psychological demands (5) Workplace support (8) Supervisor support (4) Coworker support (4). 408 66.9 (7.7) 33.5 (4.0) 33.5 (5.2) 32.9 (4.6) 23.7 (3.3) 11.3 (2.2) 12.3 (1.7). Range (min~max). Female assemblers in Taiwan+. Taiwan national survey, 2001#. 42–92 (24–96) 20–46 (12–48) 12–48 (12–48) 15–48 (12–48) 10–32 (8–32) 4–16 (4–16) 4–16 (4–16). 648 57.7 (10.3) 28.8 (5.1) 28.9 (6.3) 33.6 (4.6) 23.2 (3.2) 10.9 (2.2) 12.3 (1.7). 5,986 61.8 (9.9) 30.5 (5.0) 31.3 (6.1) 30.8 (3.7) _ 10.5 (2.1) 11.8 (1.5). *Job control = Skill discretion + Decision authority; Workplace support = Supervisor support + Coworker support, +Data from Cheng et al. (14), #Data from Cheng et al. (18).

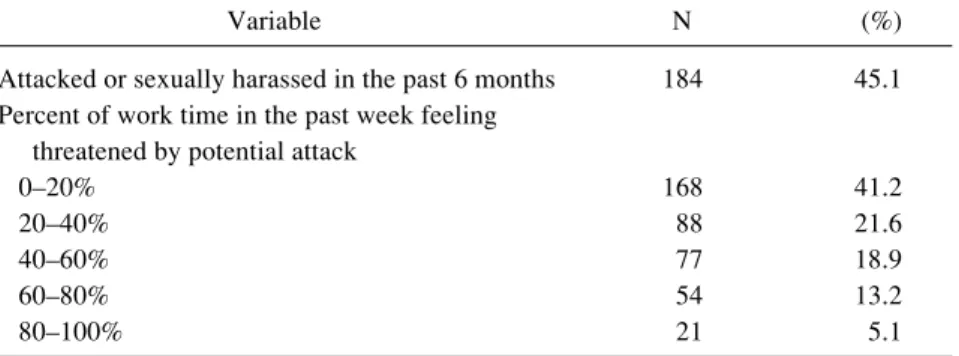

(4) Hsiu-Chuan SHEN, et al.: Stress in Psychiatry Nurses. 221. Table 3. Attacks and threatened attack in nurses in psychiatric institutions in Taiwan Variable. N. (%). Attacked or sexually harassed in the past 6 months Percent of work time in the past week feeling threatened by potential attack 0–20% 20–40% 40–60% 60–80% 80–100%. 184. 45.1. 168 88 77 54 21. 41.2 21.6 18.9 13.2 5.1. Table 4. Risk factors for perceived occupational stress* by multiple logistic regression (R2=0.15) Variable Age 40 yr or older 30–39 yr younger than 30 yr Marital status Married Single Widow/divorced/separated Job rank Nurses Administrative nurses Weekly working hours < = 40 h >40 h Work shift Fixed shift Rotating shift Job control High (≥63) Low (<63) Psychological demands Low (<31) High (≥31) Workplace social support High (≥23) Low (<23) Feeling threat of violent attack in the past one week 0%–60% >60%. N. Odds Ratio. 95%CI of OR. p-value. 75 174 159. 1 2.4 3.6. (0.8–7.9) (1.1–13.4). 0.121 0.037. 236 155 17. 1 1.1 6.9. (0.5–2.2) (1.9–24.7). 0.825 0.003. 359 49. 1 1.44. (0.5–4.3). 0.514. 281 127. 1 2.1. (1.1–3.7). 0.017. 152 256. 1 0.7. (0.4–1.5). 0.376. 307 101. 1 1.2. (0.6–2.3). 0.587. 274 134. 1 3.0. (1.4–7.4). 0.008. 303 105. 1 2.0. (1.1–3.8). 0.028. 333 75. 1 2.6. (1.3–5.1). 0.004. *Often or always under significant stress in the past one month. the C-JCQ survey in female electronics assemblers (14) are shown for comparison. Among the nurses, 16.9%, 25.2%, 50.0%, and 7.8% belonged to the “High strain”, “Low strain”, “Active”, and “Passive” groups, respectively. Concerning workplace injuries, 45.1% had. experienced attacks or sexual harassment in the past 6 months. While asked how frequently they felt the threat of being attacked or harassed in the workplace, 18.3% reported more than 60% of time in the past one week when they felt threatened by potential attacks or.

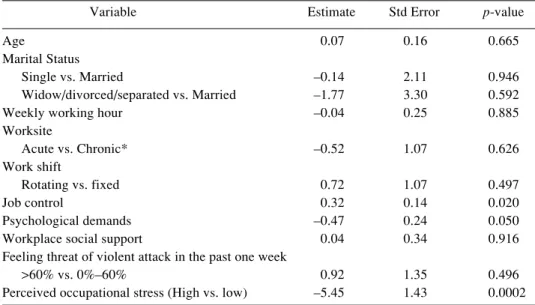

(5) 222. J Occup Health, Vol. 47, 2005. Table 5. Risk factors affecting perceived general health by multiple regression (R2=0.10) Variable Age Marital Status Single vs. Married Widow/divorced/separated vs. Married Weekly working hour Worksite Acute vs. Chronic* Work shift Rotating vs. fixed Job control Psychological demands Workplace social support Feeling threat of violent attack in the past one week >60% vs. 0%–60% Perceived occupational stress (High vs. low). Estimate. Std Error. p-value. 0.07. 0.16. 0.665. –0.14 –1.77 –0.04. 2.11 3.30 0.25. 0.946 0.592 0.885. –0.52. 1.07. 0.626. 0.72 0.32 –0.47 0.04. 1.07 0.14 0.24 0.34. 0.497 0.020 0.050 0.916. 0.92 –5.45. 1.35 1.43. 0.496 0.0002. *Acute sites included acute ward and emergency department; chronic sites included outpatient department, day-care ward, chronic ward, and administrative work. Table 6. Risk factors affecting perceived mental health by multiple regression analysis (R2=0.26) Variable Age Marital Status Single vs. Married Widow/divorce or separated vs. Married Weekly working hour Worksite Acute vs. Chronic* Work shift Rotating vs. fixed Job control Psychological demands Workplace social support Feeling threat of violent attack >60% vs. 0%–60% Perceived occupational stress (High vs. low). Estimate. Std Error. p-value. 0.24. 0.11. 0.036. –0.37 0.21 0.19. 1.5 2.4 0.18. 0.806 0.931 0.297. –0.49. 0.76. 0.516. 0.86 0.42 –0.32 0.51. 0.76 0.10 0.17 0.24. 0.257 <.0001 0.050 0.036. –0.74 –6.25. 0.96 1.00. 0.442 <.0001. *Acute sites included acute ward and emergency department; chronic sites included outpatient department, day-care ward, chronic ward, and administrative work. harassments (Table 3). Concerning perceived occupational stress, 17.2% of the nurses felt they were often or always under significant stress in the past one month (data not shown). Risk factors for perceived occupational stress were analyzed by multiple logistic regression analysis. Potential factors for the model included age, tenure, weekly work hours, education level, marital status, job rank, work site, and work shift (Table 4). The lower age. groups had higher risk of occupational stress especially in the nurses aged <30 yr (OR 3.5, 95% confidence interval, CI 1.1–12.8). Higher risk (OR 6.2, 95% CI 1.7– 22.3) as noted for martial status, widowed/divorced/ separated, as compared with married nurses. Among job control, psychological demand, and workplace support, high psychological demand and low workplace support were associated with perceived occupational stress. Among those nurses who felt threatened by potential.

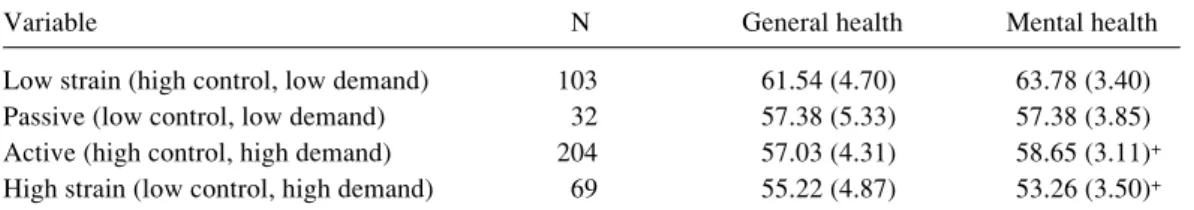

(6) Hsiu-Chuan SHEN, et al.: Stress in Psychiatry Nurses. 223. Table 7. Adjusted SF-36 mental health and general health among the four JCQ groups Variable Low strain (high control, low demand) Passive (low control, low demand) Active (high control, high demand) High strain (low control, high demand). N. General health. Mental health. 103 32 204 69. 61.54 (4.70) 57.38 (5.33) 57.03 (4.31) 55.22 (4.87). 63.78 (3.40) 57.38 (3.85) 58.65 (3.11)+ 53.26 (3.50)+. *Adjusted for age, education, marital status, weekly working hours, worksite, workplace social support, and work shift. +p<0.05, significantly different from the Low strain group by Tukey’s HSD test.. attack or harassment in the past week for 60% of time or more, the perceived stress was much higher (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4–5.1) than those who felt such threat less than 60% of the time. Predictive factors for general health scores and mental health scores by SF-36 were analyzed by multiple regression analysis. Potential factors for the model included age, weekly work hours, education level, marital status, work site, work shift, job control, psychological demand, workplace support, perceived threat of violent attack, and perceived occupational stress (Tables 5, 6). Higher job control, lower psychological demands, and lower perceived occupational stress were associated with increased general health. Higher job control, lower psychological demands, higher workplace support, and lower perceived occupational stress were associated with increased mental health. The nurses were grouped by the JCQ into Low Strain, High Strain, Active, and Passive groups (Table 7). Mental health was found to be lowest in the High Strain group, which was significantly different from the Active and Low Strain groups.. Discussion This is the first study in Taiwan to investigate occupational stress in nurses in psychiatric institutions. Almost all nurses in state-owned psychiatric institutions were included as our target population. We found a generally high self-perceived occupational stress (17.2% of the nurses felt they were often or always under significant stress in the past one month) as compared with previous studies 18, 21). Such occupational stress was associated with younger age, widow/divorced/separated marital status, high psychological demand, low workplace support, and threat of potential attacks at work. Job contents and perceived occupational stress were also risk factors for poorer mental health. In the process of modernization, self-perceived occupational stress can increase as a secular trend. In Japan, more than 50% of workers were found to have job-related distress in nation-wide surveys, and the prevalences were increasing22). Similarly, in the 1994 and 2001 national surveys for workplace safety and health. in Taiwan, 6.5% and 13.5% of employed people reported they were often or always under significant occupational stress18). In this research, the proportion of nurses (17.2%) reporting to be often or always under significant occupational stress was similar to that of a comparable sex and age group (female, aged 25–34, 16.5%) from the 2001 national survey of employees in Taiwan. Whether this is higher than nurses in non-psychiatric institutions is not known, and will be a topic for future studies. Selfperceived occupational stress is associated with JCQ results, that among the high strain, low strain, active, and passive groups, 30.9%, 6.9%, 19.9%, and 3.1% (data now shown) reported to be often or always under significant occupational stress, respectively. The job Content Questionnaire has not been applied broadly to the working population in Taiwan until recently. We compared the findings of our population with data from assemblers in electronics industries14), and the 2001 Taiwan national survey18). The nurses in this study had higher job control compared to all other populations. They also had higher demand compared to women of similar age in the 2001 Taiwan national survey. This is compatible with a previous report that nurses belong to the active class in the Karasek job model23). This is further supported by the categorization using the means of job control and demand in the national survey, which showed that approximately a half of the nurses in this study belonged to the “active” class. A high prevalence of workplace hazards was reported by the nurses in this study, i.e., 14.7% had needle-stick injury in the past 12 months (data not shown), and 45.1% experienced attack or harassment in the past 6 months. This is compatible with a previous survey, in which a rather high rate of needle-stick injuries was found in nurses in Taiwan24). Assault is one of the most important job hazards for nurses in psychiatric institutions. In suburban psychiatric hospitals, career prevalence of ever being assaulted was as high as 82%25). The prevalence of assault incidents in nurses from psychiatric hospitals in London was reported to be 32% in a 14-wk period26). These figures are similar to our findings. Perceived threat of being attacked was highly associated with the experience of being attacked or harassed (data not shown)..

(7) 224. Therefore it is likely that the threat of being attacked has become an important source of stress among nurses in psychiatric institutions. Risk factors for perceived occupational stress included younger age, widowed/divorced/separated marital status, high psychological demand, low workplace support, and threat of attack or harassment. The effect of age on perceived occupational stress was compatible with the finding of the 2001 Taiwan national survey18), in which perceived stress was highest in the working population aged 25–35, and decreased with increasing age. Psychological demand at work is often reported as associated with occupational stress. A previous study of 4 typical industries in Taiwan showed that low demand and high control were good predictors of job satisfaction 14). In this study, job control was not a predictor of perceived stress. This might be due to the fact that subjects in this study had generally high control and at such a level difference in control did not pose significant effects on perceived stress. The findings from this study are compatible with Caplan et al. who assumed that stress was associated with the feeling of threat from the work environment and a lack of satisfaction with overloaded demands27). Higher perceived occupational stress was associated with lower general health and mental health scores. Occupational stress has been related to health outcomes in the literature. Those negative health outcomes could be the results of the combined effects of insomnia, tension, anxiety, and dissatisfactory situations28). In addition, we found higher job control, lower psychological demand, and higher workplace support associated with lower mental health score, as has been suggested by Karasek et al.7, 10, 12) This is compatible with a representative survey among workers in the Baltimore area, in which three forms of depression were associated with low decision authority29). One limitation of this study was that the JCQ and the health outcome information were obtained in a crosssectional manner, making causal inference less certain. Conceptually, the analysis for risk factors should therefore be considered as association rather than causes of the health outcomes. In addition, the subjects of our study were from public-owned psychiatric institutions and therefore were likely to have better general working conditions as compared with private-owned institutions. In conclusion, a high percentage of nurses in psychiatric institutions in Taiwan belong to the “active” class of work according to the Karasek model. Perceived stress was associated with psychological demand, poor workplace support, and threat of attack. Lower general health was associated with low job control, high psychological demand, and perceived occupational stress. Lower mental health was associated with low job control, high psychological demand, low workplace support, and. J Occup Health, Vol. 47, 2005. perceived occupational stress. This investigation lays the groundwork on occupational stress among nurses in psychiatric institutions and has identified potential problems in these nurses. Further investigation on the long-term effects of job content, perceived stress, and assault are warranted. Acknowledgments: This study was supported by the Mei-Jau Grant for Preventive Medicine Research Scholarship, 2001–2002.. References 1) 2). 3). 4). 5). 6). 7). 8). 9). 10). 11). 12). 13). 14). S Davis: Violence by psychiatric inpatients. Rev Hosp and Comm Psychiat 41, 585–590 (1991) RM Haller and RH Deluty: Assaults on staff by psychiatric in-patients. A critical review. Brit J Psychiat 152, 174–179 (1988) Warchol G. Workplace Violence 1992–96. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report NCJ 168634, 1998. SHS Lee, SG Gerberich, LA Waller, A Anderson and P McGovern: Work-related assault injuries among nurses. Epidemiol 10, 685–691 (1999) Karasek R, Theorell T, eds. Health, Work-Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic Books, 1990. PL Schnall, PA Landsbergis and D Baker: Job strain and cardiovascular disease. Ann Rev Public Health 15, 381–411 (1994) R Karasek, D Baker, F Marxer, A Ahlbom and T Theorell: Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health 71, 694–705 (1981) JA Seago and F Faucett: Job strain among registered nurses and other hospital workers. JONA 27, 19–25 (1997) PA Landsbergis: Occupational stress among health care workers: A test of the job demands-control model. J Organizational Behav 9, 217–239 (1988) PA Landsbergis, PL Schnall, D Deitz, R Friedman and T Pickering: The patterning of psychological attributes and distress by “job strain” and social support in a sample of working men. J Behav Med 15, 379–405 (1992) BC Amick, I Kawachi, EH Coakley, D Lerner, S Levine and GA Colditz: Relationship of job strain and isostrain to health status in a cohort of women in the United States. Scand J Work Environ Health 24, 54– 61 (1998) J Johnson and E Hall: Job strain, work place, social support and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health 78, 1336–1342 (1988) JE Johnson, EM Hall and T Theorell: Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population. Scand J Work Environ Health 15, 271–279 (1989) Y Cheng, WM Luh and YL Guo: Reliability and.

(8) Hsiu-Chuan SHEN, et al.: Stress in Psychiatry Nurses. 15). 16). 17). 18). 19). 20). 21). Validity of the Chinese Version of the Job Content Questionnaire (C-JCQ) in Taiwanese Workers. Int J Behav Med 10, 15–30 (2002) 41st World Medical Assembly: Declaration of Helsinki: Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. B Pan Am Health Organ 24, 606–609 (1990) Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B, eds. SF36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Nimrod Press, Boston, MA, 1993. ML Rosenberg, PW O’Carroll and KE Powell: Let’s be clear: Violence is a public health problem. JAMA 267, 3071–3072 (1992) Y Cheng, YL Guo and WY Yeh: A national survey of psychosocial job stressors and their implications for health among working people in Taiwan. Int Arch Occup Env Health 74, 495–504 (2001) SJ Wang, JL Fuh, SR Lu and KD Juang: Quality of life differs among headache diagnoses: Analysis of SF-36 survey in 901 headache patients. Pain 89, 285–292 (2001) JL Fuh, SJ Wang, SR Lu, KD Juang and SJ Lee: Psychometric evaluation of a Chinese (Taiwanese) version of the SF-36 Health Survey amongst middleaged women from a rural community. Quality Life Res 9, 675–683 (2000) Tai CF, Yang SC, Yeh WY. Survey of employees’ perceptions of safety and health in the work environment in 2001 Taiwan. Inst for Occu Safety and Health (IOSH) Report #90–H304, 2002.. 225. 22) N Kawakami and T Haratani: Epidemiology of job stress and health in Japan: Review of current evidences and future direction. Ind Health 37, 174–186 (1999) 23) RA Karasek, C Brisson, N Kawakami, I Houtman, P Bongers and B Amick: The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 3, 322–355 (1998) 24) YL Guo, JSC Shiao, YC Chuang and KY Huang: Needlestick and sharp injuries among health care workers in Taiwan. Epidemiol Infect 122, 259–265 (1999) 25) E Baxter, RJ Hafner and G Holme: Assaults by patients: the experience and attitudes of psychiatric hospital nurses. Aust N Z J Psychiat 26, 567–573 (1992) 26) R Whittington and T Wykes: Violence in psychiatric hospitals: Are certain staff prone to being assaulted? J Adv Nurs 19, 219–225 (1994) 27) RD Caplan and KE Jones: Effect of work load, role ambiguity and Type A personality on anxiety, depression and heart rate. J Appl Psychol 60, 713–719 (1975) 28) TG Cumming and CL Cooper: A Cybernetic framework for studying occupational stress. Human Relation 32, 395–481 (1979) 29) H Mausner-Dorsch and WW Eaton: Psychological work environment and depression: Epidemiologic assessment of the demand-control model. Am J Public Health 90, 1765–1770 (2000).

(9)

數據

相關文件

Quadratically convergent sequences generally converge much more quickly thank those that converge only linearly.

denote the successive intervals produced by the bisection algorithm... denote the successive intervals produced by the

Wallace (1989), "National price levels, purchasing power parity, and cointegration: a test of four high inflation economics," Journal of International Money and Finance,

The purposes of this research are to find the factors of raising pets and to study whether the gender, age, identity, marital status, children status, educational level and

Umezaki,B., Tamaki and Takahashi,S., "Automatic Stress Analysis of Photoelastic Experiment by Use of Image Processing", Experimental Techniques, Vol.30 , P22-27,

In addition, the study found that mood, stress, leadership and decision-making will affect the employees’ job satisfaction1. In other words, those factors increasing or

(1980), A Conceptual Formulation for Research on Stress, In J.E.McGrat, Social and psychological factors in stress, New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. (1982), “Counselor’s Role

The purposes of this research are to find the factors of affecting organizational climate and work stress, to study whether the gender, age, identity, and