Residents’ attitudes toward island tourism development

in Taiwan

Chia-Pin Yu

School of Forestry and Resource Conservation, National Taiwan University, Taiwan simonyu@ntu.edu.tw

Yu-Chih Huang

Department of Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management, National Chi-Nan University, Taiwan yhuang@g.clemson.edu

Pa-Fang Yeh

School of Forestry and Resource Conservation, National Taiwan University, Taiwan r01625008@ntu.edu.tw

and

Pei-Hua Chao

Department of Bio-Industry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University, Taiwan d02630003@ntu.edu.tw

ABSTRACT: This study examined a proposed model of resident support for tourism

development among selected tourism development stages. The proposed model depicts the relationships among perceptions of tourism impact, tourism-related community quality of life (TCQOL), and resident support for tourism development. Considering the characteristics of island tourism and reviewed tourist arrivals database from 1986 to 2012, three tourism islands in Taiwan (Little Liuqiu, Orchid Island, and Green Island, which represent the growth, rejuvenation, and decline stages respectively) were selected. In total, 376 valid questionnaires were analyzed using path analysis with the observed variables (PA-OV) technique by AMOS. The results illustrated that the relationships among tourism impact, TCQOL, and tourism support vary among tourism development stages. In this study, the concept of destination life cycle was used to elucidate the associations among tourism development stages, tourism impact, TCQOL, and resident support for tourism development.

Keywords: destination life cycle, island tourism development, tourism-related community quality of life (TCQOL), resident attitudes, Taiwan, tourism impacts

https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.32

© 2017 ― Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada.

Introduction

With an abundance and diversity of natural and cultural resources, Taiwan has great potential for tourism development (Lee & Chien, 2008; Liu & Chou, 2016). International tourist arrivals to Taiwan have increased from 8,963,712 to 14,588,923 over the period of 1996-2016, and tourism revenues have thus reached double-digit growth (Tourism Statistics Database, 2017). As suggested by Cheng et al. (2013), island tourism, possessing the characteristics of natural ecology and historic

artefacts, has become one of the emerging tourism types in Taiwan. Island-based tourism provides a variety of nature-based attractions and activities to increase economic growth and, according to Lee et al. (2017), has experienced exponential growth in the past 10 years in Taiwan. Given the popularity of island tourism in Taiwan, it is important to understand residents’ attitudes toward tourism development on tourism islands.

Conceptual frameworks and theories of resident attitudes toward tourism development for clarifying the relationships between attitudes and resident support for tourism development were proposed in tourism impacts literature (Teye et al., 2002). Tourism theorists have provided several theoretical frameworks, such as the Irridex model (Doxey, 1975), destination life cycle (Butler, 1980), social exchange theory (SET) (Ap, 1990, 1992; Perdue et al., 1990), and the intrinsic– extrinsic framework (Faulkner & Tideswell, 1997), which identify factors influencing resident attitudes toward tourism development. The Irridex model by Doxey (1975) delineated resident attitude changes from a state of euphoria to apathy, annoyance, and perhaps antagonism, as the number of tourists increased with tourism development. Butler (1980) considered a tourism destination as a product that may undergo an evolutionary cycle and proposed a destination life cycle concept, namely the tourist area life cycle (TALC). An S-shaped curve with six stages, including exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and decline, determined according to the number of tourists, has been used to illustrate different stages of tourism destination popularity (Butler, 1980). Different stages reflect different degrees of tourism development and comprise various patterns involving the number of tourists and impact of tourism development. Moreover, researchers have investigated the variation in resident perceptions with the tourism development stage by applying Butler’s TALC model (Allen et al., 1988; Doğan, 1989; Johnson et al., 1994; Madrigal, 1993; Perdue et al., 1991; Yoon et al., 1999). The life cycle models suggest that resident attitudes change over time according to the tourism development stage, implying that resident perceptions of various types of economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts are associated with the tourism development stage.

SET has attracted substantial attention from tourism scholars for understanding resident attitudes toward and support for tourism development. According to SET, people tend to engage in an exchange process if the perceived benefits of participating in an activity or using an object outweigh the costs (Ap, 1992; Skidmore, 1975). SET postulates that residents’ opinions depend on their perceived benefits and costs of tourism, subsequently influencing their level of support for tourism (Ap, 1990, 1992). Thus, residents who benefit from tourism likely perceive tourism positively and accordingly support it. Herein, the basic assumption is that residents willingly engage in an exchange process when they perceive more benefits than costs (Jurowski et al., 1997). SET involves trading and sharing tangible and intangible resources between individuals and groups that can be material, social, or psychological in nature (Harrill, 2004). In studies on resident attitudes, three elements have been identified in the exchange process: economic, environmental, and sociocultural elements (Andriotis & Vaughan, 2003). Residents may consider not only economic benefits or costs but also other benefits or costs when evaluating the impact of tourism on their communities. Thus, SET clarifies resident reactions and support for tourism development (Ap, 1990, 1992; Gursoy et al., 2002; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Jurowski et al., 1997; Lindberg & Johnson, 1997; Madrigal, 1993; Perdue et al., 1987, 1990; Yoon et al., 2001). Additionally, host communities of tourism destinations experience diverse consequences of tourism development, these positive and/or negative impacts not surprisingly change residents’ QOL consequently. Researchers further addressed the relationships between quality of life perception and support for tourism (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Ko & Stewart, 2002).

According to the literature, several factors influence local support for tourism development, and they are moderated by the stage of tourism development in the host community. The magnitude and directions of the model of resident support for tourism development might change among different development stages (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010b). This study examined the proposed model, which illustrates the relationships among residents’ perceptions of tourism

impact, their tourism-related community quality of life (TCQOL), and their support for tourism development among tourism development stages. The model explains the factors influencing resident support for tourism at a tourism destination, thus facilitating the planning of strategic development programs at three tourism destinations in Taiwan. The results can specifically aid tourism practitioners, researchers, and policymakers in identifying crucial factors contributing to TCQOL and residents’ support for tourism from the residents’ perspective.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Tourism development has numerous effects on a tourism destination and the lives of the host residents. Studies on resident perceptions of tourism impact have focused on the collective beliefs of residents on the impact of tourism development. The results of tourism impact studies have identified residents’ perceived tourism impact regarding economic, sociocultural, and environmental benefits and costs (Andereck & Jurowski, 2006; Jurowski, 1994; Marcouiller, 1997). Empirical evidence of resident attitudes toward tourism development has illustrated that six types of tourism impact dynamically change resident perceptions of CQOL (Allen et al., 1993; Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Andereck et al., 2007; Andereck & Vogt, 2000; Liu et al., 1986), implying that resident CQOL is an endogenous or dependent variable associated with tourism impact. Studies have examined the complete effects of positive and negative tourism impact on CQOL as well as the effect of a particular type of tourism impact on CQOL (Ko & Stewart, 2002; Roehl, 1999; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009). Therefore, for extensive exploration of how tourism influences resident CQOL, the following six hypotheses are proposed, which are based on the aforementioned conceptual and empirical perspectives:

Hypothesis 1: Residents’ perceived tourism impact in a particular dimension affects TCQOL. H1a: Resident perceived positive economic impact is positively associated with TCQOL. H1b: Resident perceived negative economic impact is negatively associated with TCQOL. H1c: Resident perceived positive sociocultural impact is positively associated with TCQOL. H1d: Resident perceived negative sociocultural impact is negatively associated with TCQOL. H1e: Resident perceived positive environmental impact is positively associated with TCQOL. H1f: Resident perceived negative environmental impact is negatively associated with TCQOL.

Resident support for tourism development has been considered a critical dependent variable in the resident attitudes study model (Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004). Numerous studies have revealed that residents’ positive and negative perceptions of tourism impact predict their support for tourism development (e.g., Andereck & Vogt, 2000; Ap, 1992; Dyer et al., 2007; Getz, 1994; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Jurowski et al., 1997; Ko & Stewart, 2002; McGehee & Andereck, 2004; Perdue et al., 1990). Tourism impact studies have suggested that residents’ perceptions of positive and negative economic, sociocultural, and environmental consequences predict their support for tourism development. Furthermore, resident support for tourism development is positively associated with perceived positive tourism impact and negatively associated with perceived negative tourism impact (Dyer et al., 2007; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Jurowski et al., 1997; King et al., 1993; Ko & Stewart, 2002; McGehee & Andereck, 2004; Perdue et al., 1990; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2001). Based on these conceptual and empirical perspectives, the following six hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Residents’ perceived tourism impact in a particular dimension affects their support for tourism development. H2a: Residents’ perceived positive economic impact is positively associated with their support

for tourism development.

H2b: Residents’ perceived negative economic impact is negatively associated with their support for tourism development.

H2c: Residents’ perceived positive sociocultural impact is positively associated with their support for tourism development.

H2d: Residents’ perceived negative sociocultural impact is negatively associated with their support for tourism development.

H2e: Residents’ perceived positive environmental impact is positively associated with their support for tourism development.

H2f: Residents’ perceived negative environmental impact is negatively associated with their support for tourism development.

Tourism development influences residents’ community living experience, and consequently, their perceived community satisfaction can predict support for tourism development; thus, researchers have suggested that community satisfaction should be integrated into tourism development models (Ko & Stewart, 2002; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009). Furthermore, residents’ satisfaction with neighbourhood or community conditions and with community services predicts their support for additional tourism development (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010a, 2010b). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Residents’ perceived TCQOL is positively associated with their support for tourism development. Researchers have applied the concept of Butler’s TALC model to investigate how resident perceptions, including perceived tourism impact and CQOL, vary with the tourism development stage (Allen et al., 1988; Johnson et al., 1994; Madrigal, 1993; Perdue et al., 1991). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Residents’ perceived tourism impact, perceived tourism support, and CQOL differ among tourism development stages.

To fulfill the research purpose, the proposed model and hypotheses were developed with reference to the literature on resident attitudes (Figure 1). Moreover, the proposed model was examined among three selected study sites.

Methodology

Selection of study sites

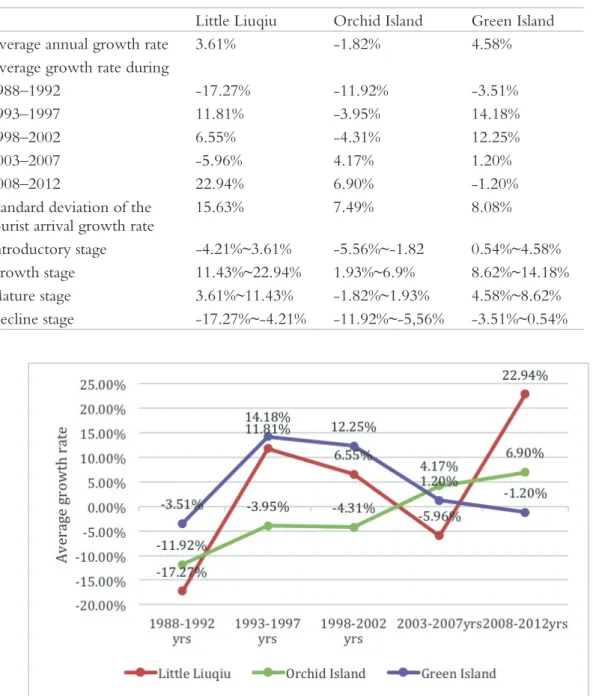

In this study, the tourism development stage was considered as a factor. Conceptually, tourist areas undergo a detectable evolution cycle of tourism development. Based on tourist arrivals and annual growth rate, Haywood (1986) identified four tourism development stages: (1) introductory [from the mean tourist arrival growth rate (TAGR) minus 0.5 standard deviations of the TAGR to the mean TAGR during the available data periods], (2) growth [from the mean TAGR plus 0.5 standard deviations of the TAGR to the highest TAGR], (3) maturity [from the mean TAGR to the mean plus 0.5 standard deviations of the TAGR], and (4) decline [from the lowest TAGR to the mean TAGR minus 0.5 standard deviations of the TAGR]. The development stage criteria calculation is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Tourism development stage criteria calculation. (Source: Haywood, 1986)

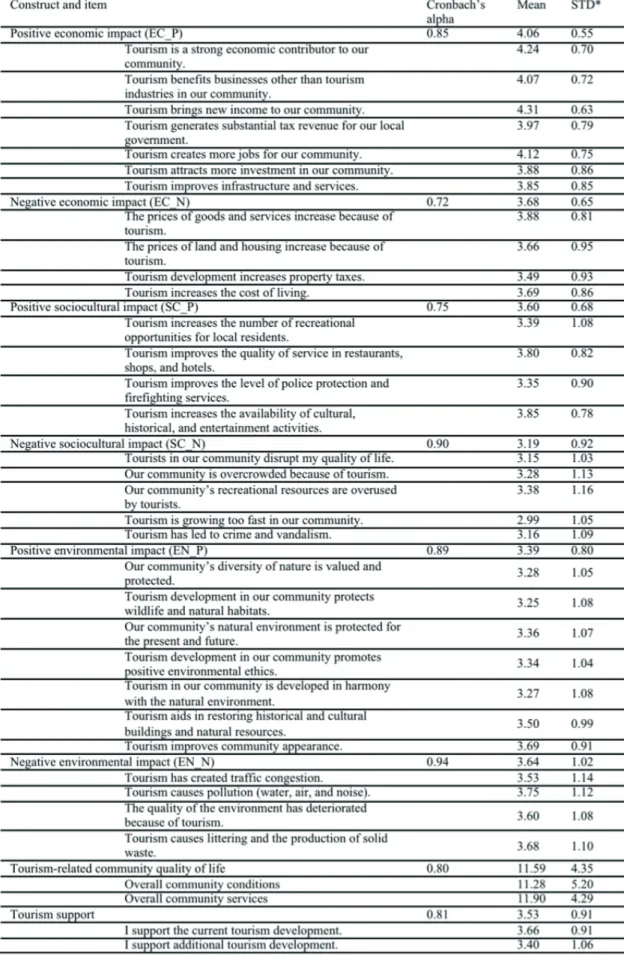

The current study used data from the Taiwan Tourism Statistics (2012) for selecting tourism destinations suitable for each tourism development stage and analyzed the tourist arrival database containing approximately 6,000 data points spread over 450 tourism destinations from 1986 to 2012. Each tourism destination was reviewed using Haywood’s (1986) criteria. Assessing the number of tourists and the degree of tourism development, few tourism destinations were classified in the exploration stage: the exploration stage of tourism islands was absent from 450 contemporary tourism destinations (Taiwan Tourism Statistics, 2012). This research, accordingly, examined the application of Tourism Life Cycle in the stages of growth, rejuvenation, and decline. Moreover, considering the tourism development type and context, three tourism islands were selected as study sites: Little Liuqiu, Orchid Island, and Green Island. The three selected islands, like other tourism islands, take advantage of geographic characteristics and associated with cultural and natural experiences (Baldacchino, 2013). Additionally, tourism plays an important role of their economy (Gossling & Wall, 2007; Karampela et al., 2016). Because of the average growth rate during 2008-2012, Little Liuqiu (22.94%) and Green Island (-1.20%) were identified to be at the growth and decline stages, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 2). Tourist arrivals growth rate in Orchid Island expanded (6.90%) recently and Orchid Island was assumed to be in the growth stage as per the aforementioned criteria. However, considering the past development cycle, Orchid Island was a popular tourism destination the 1980s and the tourist arrivals remained low thereafter. Thus, Orchid Island was identified to be in a rejuvenation stage. Therefore, Little Liuqiu, Orchid Island, and Green Island were selected for studying the growth, rejuvenation, and decline stages, respectively.

Table 2: Average growth rates of the three study sites.

Figure 2: Average growth rate trends at three study sites.

The study sites

Little Liuqiu, located in Pingtung County, Taiwan, has approximately 13,000 residents and is famous for its coral ecosystem as well as its local culture, with fisheries being a crucial industry. Recently, Little Liuqiu has become a well-known tourism destination. The tourist arrivals have substantially increased in the past decade, with an approximately 25% TAGR from 2006 to 2012 (see Figure 3).

Orchid Island is located on the southeastern coast of Taiwan, and approximately 5,000 residents currently inhabit the island. Orchid Island is famous for its natural resources and aboriginal culture. The Tao tribe has lived on this island for centuries. The island was a popular tourist destination during the 1980s. During the 1990s, tourism development in this island remained slow and steady. However, from 2006 to 2012, tourist arrivals increased at a TAGR of approximately 8% (see Figure 4).

Green Island is a small volcanic island, located off the eastern coast of Taiwan. More than 3,500 residents inhabit this island. On Green Island, tourism has been a crucial economic force for

Little Liuqiu Orchid Island Green Island Average annual growth rate 3.61% -1.82% 4.58% Average growth rate during

1988–1992 -17.27% -11.92% -3.51%

1993–1997 11.81% -3.95% 14.18%

1998–2002 6.55% -4.31% 12.25%

2003–2007 -5.96% 4.17% 1.20%

2008–2012 22.94% 6.90% -1.20%

Standard deviation of the tourist arrival growth rate

15.63% 7.49% 8.08%

Introductory stage -4.21%~3.61% -5.56%~-1.82 0.54%~4.58% Growth stage 11.43%~22.94% 1.93%~6.9% 8.62%~14.18% Mature stage 3.61%~11.43% -1.82%~1.93% 4.58%~8.62% Decline stage -17.27%~-4.21% -11.92%~-5,56% -3.51%~0.54%

local prosperity. In the 1990s, Green Island was included in the list of East Coast National Scenic Areas, resulting in an improved infrastructure (e.g., water, electricity, and airport facilities), increasing the number of tourists; consequently, most residents relied on tourism for their living. Tourist arrivals have declined since 2006, and the average TAGR from 2006 to 2012 was -1.2% (Figure 5).

Figure 3: Tourist arrivals in Little Liuqiu (1986–2012).

Figure 4: Tourist arrivals at Orchid Island (1986–2012).

Figure 5: Tourist arrivals at Green Island (1986–2012).

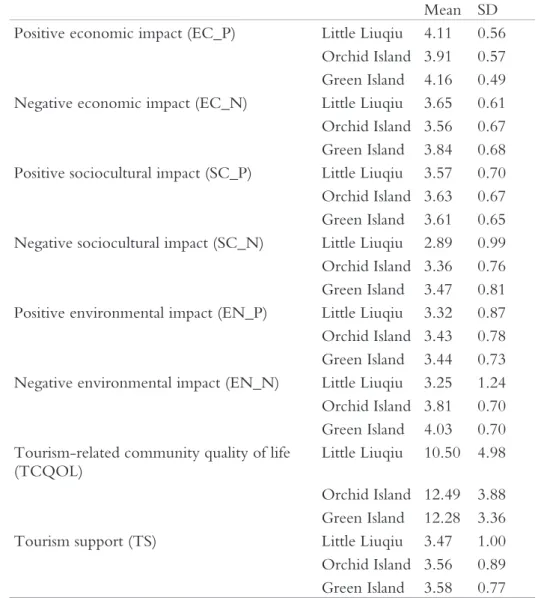

Measurement

The indicators of resident perceptions of tourism impact and support for tourism development were derived from several empirical studies by using five Likert scale items (Dyer et al., 2007; Ko & Stewart, 2002; Lankford & Howard, 1994; Liu & Var, 1986; Milman & Pizam, 1988; Perdue et al., 1987; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009). TCQOL encompasses resident perceptions of community services and conditions; in this study, the scales of resident perceptions of satisfaction, importance, and the tourism effect from the Likert scale were incorporated for measuring overall resident satisfaction with community

services and conditions in the context of tourism development (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011 Brown et al., 1998; Massam, 2002; Sirgy & Cornwell, 2001; Sirgy et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2014). Data collection and analysis approach

Because the study sites were located in remote areas of Taiwan, this study was conducted using an online survey for data collection from May to June 2014. We hired a professional online survey company, Pollster.com, to recruit participants. After elimination of the incomplete questionnaires and the checking of the postal code of each questionnaire, 376 responses were retained for analysis. Resident perceptions of tourism impact, TCQOL, and support for tourism development as well as respondent sociodemographic characteristics were identified. Data were stored and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 16.0 and Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS; version 17.0) software packages. Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 were tested using the path analysis with observed variables (PA-OV) technique through AMOS. For Hypothesis 4, the proposed model with controlled structural weights was compared at different tourism development stages through invariance analysis involving the testing of the equivalency of factors (Bollen, 1989).

Results and discussion

Respondent characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 3. The majority of the respondents were female (54.8%), aged 26-45 years (55.3%), and they were mainly college graduates (69.4%). In Little Liuqiu, more than 50% of the respondents were female, major participants aged 26-45 years (48.4%), and 71.7% were college graduates. On Orchid Island, the majority of the respondents were female (58.7%), aged 26-45 years (56.9%), and 69.7% were college graduates; however, a few respondents were only grade school graduates (2.8%). On Green Island, the sex distribution was even, with 63.9% of the respondents aged 26-45 years and 65.7% being college graduates.

Scale properties and reliability

Descriptive analysis was conducted on the constructs of tourism impact, TCQOL, and support for tourism development. Table 4 illustrates the means and standard deviations for each indicator in each construct. Tourism has both positive and negative economic effects on a host community. The descriptive statistics in Table 4 display the mean score of each indicator from an economic perspective. Most respondents agreed that they and the community benefit economically from tourism (M = 4.24, STD = 0.70). Moreover, the respondents reported that tourism generates new income (M = 4.31, STD = 0.63), creates employment (M = 4.12, STD = 0.75) and investment opportunities (M = 3.88, STD = 0.86), and provides other benefits. Nevertheless, the respondents were uncertain regarding the negative economic consequences of tourism. Considering the sociocultural impact on a host community, tourism generates positive and negative consequences. The results presented in Table 4 indicate that the residents agreed that they perceived positive sociocultural consequences. The respondents agreed that tourism improves the service quality in restaurants, shops, and hotels (M = 3.80, STD = 0.82) as well as the service quality of police and firefighters (M = 3.35, STD = 0.90). The respondents also indicated that tourism produces a mild negative sociocultural impact on the communities. From an environmental perspective, the respondents asserted that tourism improves community appearance (M = 3.69, STD = 0.91) and facilitates the restoration of buildings and natural resources (M = 3.50, STD = 0.99). A few negative environmental consequences were perceived, such as traffic congestion (M = 3.53, STD = 1.14), pollution (M = 3.75, SD = 1.12), and environmental deterioration (M = 3.60, STD = 1.08).

Eight constructs, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.72–0.94, which is higher than the recommended level, were presented in this study (see Table 4). This indicates that the variables exhibited a strong correlation within their construct grouping and that they were internally consistent (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Results of Hypothesis Testing

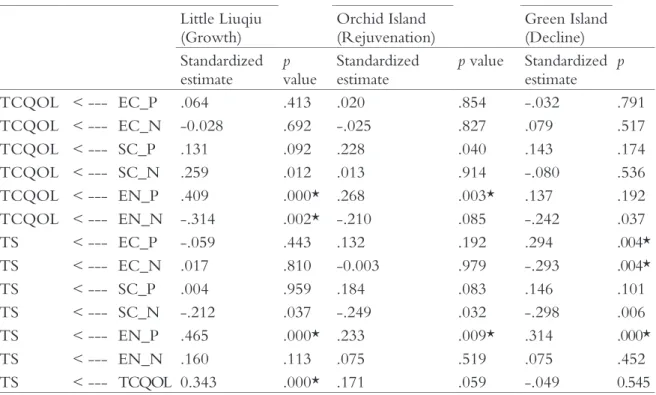

A model that is a combination of observed variables was used. Table 5 highlights the means and standard deviations of six perceived types of tourism impact, TCQOL, and tourism support. Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 were further tested in this study by using the PA-OV technique through AMOS. For Hypothesis 4, the proposed model was compared among tourism development stages through invariance analysis with controlled structural weights.

The overall model fit for Little Liuqiu was χ2 (4) = 11.645 (p = 0.020), comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.816, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.110; χ2 (4) = 4.669 (p = 0.323), CFI = 0.997, and RMSEA = 0.039 for Orchid Island; and χ2 (4) = 8.69 (p = 0.020), CFI = 0.982, and RMSEA = 0.105 for Green Island. The results indicate that the structural models have acceptable overall model fit (Table 6); thus, the hypothesis testing was reliable. The results of model testing are presented in Table 7. In Little Liuqiu, four paths, EN_P to TCQOL, EN_N to TCQOL, EN_P to TS, and TCQOL to TS, were significant. Moreover, on Orchid Island, two paths, EN_P to TCQOL and EN_P to TS, were significant. Finally, on Green Island, four paths, EC_P to TS, EC_N to TS, SC_N to TS, and EN_P to TS, were significant.

Table 5: Descriptive results of tourism impact, TCQOL, and tourism support.

Table 6: Overall model fit indices of the study sites.

Mean SD Positive economic impact (EC_P) Little Liuqiu 4.11 0.56

Orchid Island 3.91 0.57 Green Island 4.16 0.49 Negative economic impact (EC_N) Little Liuqiu 3.65 0.61 Orchid Island 3.56 0.67 Green Island 3.84 0.68 Positive sociocultural impact (SC_P) Little Liuqiu 3.57 0.70 Orchid Island 3.63 0.67 Green Island 3.61 0.65 Negative sociocultural impact (SC_N) Little Liuqiu 2.89 0.99 Orchid Island 3.36 0.76 Green Island 3.47 0.81 Positive environmental impact (EN_P) Little Liuqiu 3.32 0.87 Orchid Island 3.43 0.78 Green Island 3.44 0.73 Negative environmental impact (EN_N) Little Liuqiu 3.25 1.24 Orchid Island 3.81 0.70 Green Island 4.03 0.70 Tourism-related community quality of life

(TCQOL)

Little Liuqiu 10.50 4.98 Orchid Island 12.49 3.88 Green Island 12.28 3.36 Tourism support (TS) Little Liuqiu 3.47 1.00 Orchid Island 3.56 0.89 Green Island 3.58 0.77

Little-Liuqiu (G) Orchid Island (R) Green Island (M)

X2 11.645 4.669 8.69

Df 4 4 4

P .020 .323 .069

CFI .986 .997 .982

Table 7: Model testing results of the study sites. (Note: Significance was set at the 0.01 level)

Table 8: Hypothesis testing at the three study sites.

Hypothesis 1 assumes that resident perceived tourism impact in a particular dimension affects TCQOL. Both positive and negative economic and sociocultural impact affecting TCQOL was not supported in the growth, rejuvenation, or decline stage (Table 8). Positive environmental impact affecting TCQOL was supported in Little Liuqiu and on Orchid Island; negative environment impact affecting TCQOL was supported in Little Liuqiu. The results imply that residents in the growth stage are more concerned with both positive and negative effects of

Little Liuqiu (Growth) Orchid Island (Rejuvenation) Green Island (Decline) Standardized estimate p value Standardized estimate p value Standardized estimate p TCQOL < --- EC_P .064 .413 .020 .854 -.032 .791 TCQOL < --- EC_N -0.028 .692 -.025 .827 .079 .517 TCQOL < --- SC_P .131 .092 .228 .040 .143 .174 TCQOL < --- SC_N .259 .012 .013 .914 -.080 .536 TCQOL < --- EN_P .409 .000* .268 .003* .137 .192 TCQOL < --- EN_N -.314 .002* -.210 .085 -.242 .037 TS < --- EC_P -.059 .443 .132 .192 .294 .004* TS < --- EC_N .017 .810 -0.003 .979 -.293 .004* TS < --- SC_P .004 .959 .184 .083 .146 .101 TS < --- SC_N -.212 .037 -.249 .032 -.298 .006 TS < --- EN_P .465 .000* .233 .009* .314 .000* TS < --- EN_N .160 .113 .075 .519 .075 .452 TS < --- TCQOL 0.343 .000* .171 .059 -.049 0.545 Little Liuqiu (Growth stage) Orchid Island (Rejuvenation stage) Green Island (Decline stage) Paths Hypotheses Results Results Results EC_P → TCQOL H1a Rejected Rejected Rejected EC_N → TCQOL H1b Rejected Rejected Rejected SC_P → TCQOL H1c Rejected Rejected Rejected SC_N → TCQOL H1d Rejected Rejected Rejected EN_P → TCQOL H1e Accepted Accepted Rejected EN_N → TCQOL H1f Accepted Rejected Rejected EC_P → TS H2a Rejected Rejected Accepted EC_N → TS H2b Rejected Rejected Accepted SC_P → TS H2c Rejected Rejected Rejected SC_N → TS H2d Rejected Rejected Accepted EN_P → TS H2e Accepted Accepted Accepted EN_N → TS H2f Rejected Rejected Rejected TCQOL → TS H3 Accepted Rejected Rejected

environmental impact on their CQOL. In the rejuvenation stage, the host community’s major concern regarding CQOL was positive environment effects. Notably, residents in the decline stage reported that the tourism impact did not influence their CQOL. This might have been due to the limited tourism impact with regard to the current tourism development, which could not considerably affect their lives. Positive tourism impact may improve resident CQOL, whereas negative tourism impact may reduce it, but this may not always be true in practice. This phenomenon may be explained by the differences in the degree of tourism development and the capacity to absorb tourism impact. This concept supports the principles of life cycle models, implying that resident perceptions of various types of economic, sociocultural, and environmental impact on CQOL are specifically associated with the tourism development stage.

Considering the influence of a particular type of tourism impact domain on resident support for tourism development (Hypothesis 2), the results indicated that both positive and negative economic impact affected tourism support in the decline stage (Green Island). Additionally, negative sociocultural impact affected tourism support in the decline stage (Green Island). Furthermore, positive environmental impact affecting tourism support was supported among the growth, rejuvenation, and decline stages. The results imply that both positive economic impact and CQOL are the residents’ major concerns in the growth stage regarding their support for tourism. In the rejuvenation stage, the residents highlighted their support for tourism on the basis of environmental quality. The residents in the decline stage considered economic development, negative sociocultural impact, and environmental quality as determinant factors for their support for tourism. Furthermore, the residents’ support for tourism development was positively associated with perceived positive tourism impact and negatively associated with perceived negative tourism impact (Dyer et al., 2007; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Jurowski et al., 1997; King et al., 1993; Ko & Stewart, 2002; McGehee & Andereck, 2004; Perdue et al., 1990; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2001). Overall, the results are consistent with those of previous empirical studies. The nonsignificant relationships may be explained by the importance that communities place on tourism (Akis et al., 1996; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Husbands, 1989).

Moreover, the results indicated that TCQOL influences resident support for tourism development (Hypothesis 3) only in the growth stage (Little Liuqiu). Although empirical studies have integrated community satisfaction into resident attitude models (Ko & Stewart, 2002; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010a, 2010b; Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2009), their results have been inconsistent. For example, Ko and Stewart (2002) identified no evidence of the relationship between community satisfaction and support for tourism; however, Vargas-Sanchez et al. (2009) revealed a significantly negative relationship between community satisfaction and support for additional tourism development at their study site. A reason for this disparity may have been the high degree of context sensitivity at the study sites.

For Hypothesis 4, the structural weights were controlled among the three models, and the results were significant [χ2 (39) = 164.453, p < 0.05]. The proposed model revealed differences among tourism development stages. The results indicated that this model reports the differences among tourism development stages, illustrating that these stages potentially moderate the relationships among tourism impact, TCQOL, and tourism support.

Conclusion

By using a destination life cycle model and SET, this study clarified the effects of residents’ perception of tourism impact on their CQOL and those of their perceived tourism impact and CQOL on their support for tourism development. Furthermore, it compared the relationships and demonstrated the differences among tourism impact, TCQOL, and tourism support among tourism development stages. Conceptually, SET postulates that residents’ perceived benefits and costs of tourism subsequently influence their level of support for tourism. However, this may not be universally applicable to tourism destinations.

This study can aid in the planning of strategic development programs for tourism destinations. The analytical framework can facilitate tourism practitioners’ understanding of the factors influencing residents’ CQOL and their support for tourism at a tourism destination. Specifically, based on the findings, several suggestions for local tourism practitioners are proposed: 1. For Little Liuqiu, environmental sustainability actions can improve resident CQOL. An environmental protection plan can contribute to resident support for tourism development and ensure high-quality local community services.

2. An environmental protection plan could considerably influence residents’ CQOL and their support for tourism on Orchid Island.

3. For increasing the level of support for tourism on Green Island, tourism economic initiatives and environmental protection policies should be included in local development. The cost of living and negative sociocultural impact should be further controlled.

This research helps tourism practitioners identify residents’ concerns regarding their CQOL and support for tourism, indicating that resource planners must preserve the factors that are most valued by the people in a community and develop appropriate programs during tourism development. Enhancing resident CQOL can generate stronger support for tourism; thus, reaction to tourism development and tourists may be more receptive and friendly. This approach can provide a more satisfactory tourist experience and may result in repeated visits and positive word-of-mouth advertising. Moreover, this study provided a useful framework for monitoring resident experiences of tourism development. Tourism practitioners can adopt this framework to identify how tourism impact alters resident perceived CQOL and subsequently influences support for tourism throughout the tourism development stages. This paper contributes to theoretical advancement in the field of resident attitude studies by considering both the tourism development life cycle model and SET for explaining residents’ perceived tourism impact, their CQOL, and their support for tourism development.

This study contributes to the literature on islanders’ perceptions of tourism development and its impacts on tourism-related community quality of life by validating the research frameworks of destination life cycle (Butler, 1980) and social exchange theory (Ap, 1990, 1992). The findings of this study offer insights to scholars in the relam of island tourism who seek to understand residents’ perceptions and support for tourism development, reinforcing the TALC and SET propositions arrived at from previous studies (e.g. Chuang, 2013; Hunt & Stronza, 2014; Lundberg, 2015; Nunkoo & So, 2016). Another contribution of this study is that it expands scholarship and knowledge about residents’ perception of tourism development by examining three islands in which the tourism industry has a strong influence on residents’ community quality of life, in line with past studies (Andereck & Nyaupane, 2011; Allen et al., 1988; Yu et al., 2014). While this research posits an integrated model in understanding resident perceived tourism impacts, community quality of life, and their support for tourism among development stages, tourism development could contribute to regional inequality that affects standard of living of host community (Chancellor et al., 2011). Researchers further argue that tourism destinations consist of different types of places (e.g. tourism, non-tourism, and shared) and associated different levels of impact and attitude to tourism (McKercher et al., 2015). A more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between social geography and residents’ attitudes would allow tourism practitioners to mitigate concerns of tourism development of host community. This research theme contributes to building a stronger knowledge in residents’ attitudes study.

This study collected data by employing an online survey, requiring research participants to access to the Internet and be comfortable with computer use. As a result, the current study lacks

participation of elderly people (above 65 years old), which poses a limitation to our comprehensive understanding of residents’ attitudes toward tourism development.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (R.O.C.) under research grant MOST 102-2410-H-002-164.

References

Akis, S., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: the case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17(7), 481-494.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00066-0

Allen, L.R., Hafer, H.R., Long, P.T., & Perdue R.R. (1993). Rural residents’ attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 31(4), 27-33.

https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759303100405

Allen, L.R., Long, P.T., Perdue, R.R., & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 27(1), 16-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728758802700104

Andereck, K.L. & Jurowski, C. (2006). Tourism and quality of life. In G. Jennings & N.P. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality Tourism Experiences (pp. 136-154). Oxford: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-7811-7.50016-X

Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G.P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 248-260.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

Andereck, K.L., Valentine, K.M., Vogt, C.A., & Knopf, R.C. (2007). A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(5), 483-502. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost612.0

Andereck, K.L. & Vogt, C.A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104

Andriotis, K., & Vaughan, R. D. (2003). Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: the case of Crete. Journal of Travel Research, 42(2), 172-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503257488

Ap, J. (1990). Residents’ perceptions research on the social impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(4), 610-616. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90032-M Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4),

665-690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

Baldacchino, G. (2013). Island tourism, In A. Holden & D. A. Fennell (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of tourism and the environment (pp. 200-208). London: Routledge.

Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118619179

Brown, I., Raphael, D., & Renwick, R. (1998). Quality of life profile, 2. Toronto: University of Toronto: Quality of Life Research Unit, Center for Health Promotion.

Butler, R.W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien, 24(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

Chancellor, C.C., Yu, C.P., & Cole, S.T. (2011). Exploring quality of life perceptions in rural midwestern (USA) communities: an application of the core-periphery concept in a tourism development context. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(5), 496-507. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.823

Cheng, T.M., C., Wu, H., & Huang, L.M. (2013). The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(8), 1166-1187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.750329

Chuang, S.T. (2013). Residents’ attitudes toward rural tourism in Taiwan: a comparative viewpoint. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(2), 152-170.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1861

Doǧan, H.Z. (1989). Forms of adjustment: sociocultural impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(2), 216-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(89)90069-8

Doxey, G.V. (1975). A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants’ methodology and research inferences. In Conference Proceedings of the sixth annual conference of the Travel Research Association. San Diego, CA.

Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., & Carter, J. (2007). Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Management, 28(2), 409-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.002 Faulkner, B. & Tideswell, C. (1997). A framework for monitoring community impacts of

tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 5(1), 3-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589708667273

Getz, D. (1994). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism: a longitudinal study in Spey Valley, Scotland. Tourism Management, 15(4), 247-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)90041-8 Gössling, S., & Wall, G. (2007). Island tourism. In G. Baldacchino (Ed.), A world of islands: an

island studies reader (pp. 429-453). Luqa & Charlottetown: Agenda Academic & Institute of Island Studies.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: a structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7

Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D.G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism: an improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495-516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

Harrill, R. (2004). Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: a literature review with implications for tourism planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 18(3), 251-266.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412203260306

Haywood, K.M. (1986). Can tourist life cycle be made operational? Tourism Management, 7(3), 154-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(86)90002-6

Hunt, C., & Stronza, A. (2014). Stage-based tourism models and resident attitudes towards tourism in an emerging destination in the developing world. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(2), 279-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.815761

Husbands, W. (1989). Social status and perception of tourism in Zambia. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(2), 237-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(89)90070-4

Johnson, J.D., Snepenger, D.J., & Akis, S. (1994). Residents’ perceptions of tourism

development. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 629-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90124-4

Jurowski, C. (1994). The interplay of elements affecting host community resident attitudes toward tourism: a path analytic approach. Doctoral dissertation. Virginia Tech University, Blacksburg, VA.

Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williams, D. R. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2), 3-11.

https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759703600202

Karampela, S., Kizos, T., & Spilanis, I. (2016). Evaluating the impact of agritourism on local development in small islands. Island Studies Journal, 11(1), 161-176.

King, B., Pizam, A., & Milman, A. (1993). Social impacts of tourism: host perceptions. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(4), 650-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90089-L Ko, D.W., & Stewart, W.P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for

tourism development. Tourism Management, 23(5), 521-530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

Lankford, S.V., & Howard, D.R. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(1), 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90008-6 Lee, C.C., & Chien, M.S. (2008). Structural breaks, tourism development, and economic

growth: evidence from Taiwan. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 77(4), 358-368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2007.03.004

Lee, T.H., Jan, F.H., Tseng, C.H., & Lin, Y.F. (2017). Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: a case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1354865

Lindberg, K., & Johnson, R.L. (1997). Modeling resident attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 402-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80009-6 Liu, C.H.S., & Chou, S.F. (2016). Tourism strategy development and facilitation of integrative

processes among brand equity, marketing and motivation. Tourism Management, 54, 298-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.014

Liu, J.C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(2), 193-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90037-X Lundberg, E. (2015). The level of tourism development and resident attitudes: a comparative

case study of coastal destinations. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(3), 266-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1005335

Madrigal, R. (1993). A tale of tourism in two cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(2), 336-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90059-C

Marcouiller, D.W. (1997). Toward integrative tourism planning in rural America. Journal of Planning Literature, 11(3): 337-357. https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229701100306 Massam, B.H. (2002). Quality of life: public planning and private living. Progress in Planning,

58(3), 141-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(02)00023-5

McGehee, N.G., & Andereck, K.L. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131-140.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

McKercher, B., Wang, D., & Park, E. (2015). Social impacts as a function of place change. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 52-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.002 Milman A., & Pizam, A. (1988). Social impacts of tourism on central Florida. Annals of Tourism

Research, 15(2), 191-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90082-5

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010a). Modeling community support for a proposed integrated resort project. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 257-277.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903290991

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010b). Residents’ satisfaction with community attributes and support for tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(2), 171-190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010384600

Nunkoo, R., & So, K.K.F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism: testing alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847-861.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972

Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. Perdue, R.R., Long, P.T., & Allen, L.R. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals

of Tourism Research, 17(4), 586-599. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90029-Q Perdue, R.R., Long, P.T., & Allen, L.R. (1987). Rural resident tourism perceptions and

attitudes. Annals of Tourism Research, 14(3), 420-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(87)90112-5

Perdue, R.R., Long, P.T., & Gustke, L.D. (1991). The effect of tourism development on objective indicators of local quality of life. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual TTRA Conference, Salt Lake City, UT.

Roehl, W.S. (1999). Quality of life issues in a casino destination. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 223-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00203-8

Sirgy, M.J., & Cornwell, T. (2001). Further validation of the Sirgy et al.’s measure of community quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 56(2), 125-143.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012254826324

Sirgy, M.J., Rahtz, D.R., Cicic, M., & Underwood, R. (2000). A method for assessing residents’ satisfaction with community-based services: a quality-of-life perspective. Social Indicators Research, 49(3), 279-316. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006990718673

Skidmore, W. (1975). Theoretical thinking in sociology. New York & London: Cambridge University Press.

Taiwan Tourism Statistics (2012). Taiwan Tourism Statistics.

http://recreation.tbroc.gov.tw/asp1/statistics/year/INIT.ASP (in Chinese). Teye, V., Sirakaya, E., & Sonmez, S.F. (2002). Residents’ attitudes toward tourism

development. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 668-688. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00074-3 Tourism Statistics Database (2017). Tourism Statistics Database.

http://stat.taiwan.net.tw/system/index.html

Vargas-Sanchez, A., Plaza-Mejia, M.A., & Porras-Bueno, N. (2009). Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. Journal of Travel Research, 47(3), 373-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508322783 Yoon, Y., Chen, J.S., & Gürsoy, D. (1999). An investigation of the relationship between

tourism impacts and host communities’ characteristics. Anatolia, 10(1), 29-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.1999.9686970

Yoon, Y., Gursoy, D., & Chen, J.S. (2001). Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modeling. Tourism Management, 22(4), 363-372.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00062-5

Yu, C.P., Cole, S.T., & Chancellor, C.C. (2014). Assessing community quality of life in the context of tourism development. Applied Research in Quality Life, 11(1), 147-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9359-6