Situational Leadership Style Identified for Taiwanese Executives

in Mainland China

Peng-Hsian Kao1, Hsin Kao1, Thun-Yun Kao2

1. China institute of Technology

2. Takming University of Science and Technology

E-mail : seankao74@yahoo.com

Abstract

China’s economic power influences the global business environment and draws companies to Mainland China; this applies pressure to Taiwanese investment companies as China opens its market to a global society. The purpose of this study was to investigate the differences among Taiwanese executives’ situational leadership style and demographic characteristics in the traditional enterprises in Shanghais region of Mainland China. This study used a quantitative research methodology. The Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ) was used to measure perceived situational leadership style. The findings show that there was a significant difference among executives’ delegating leadership style based on their age and their years of working in the business.

Keyword: Situational leadership, Mainland China, Taiwanese Executives

1. Introduction

As the East Asia market has grown, its influence on the world economy has become more significant [1]. There are two important economic powers in this market: Mainland China and Taiwan. Control over China’s economy has been decentralized in recent years [2]. Because of economic reforms, what was once a very rigid and centralized economy is becoming a market economy. China’s “open policy” has ended a decade-long isolation that had been in place during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), and allowed China to become a part of the global market. This openness to the international market has brought both new technology and valuable foreign investment to China, increasing its economic growth and aiding in a much-needed modernization. This openness to foreign investors was a drastic change from China’s socialist policy of self-reliance.

Attracted by cheaper raw materials and a cheap labor force in China, Taiwanese companies, who share the same culture and language with the people of the mainland, have been enthusiastic about investing in Mainland China. For the organization to operate, executives must not only control the business direction and procedures, they must also lead employees. According to Erven [3], “Every business needs leadership. Leadership is one of the ways that managers affect the behavior of people in the business. Most successful managers are also successful leaders. They get people to work to accomplish the organization’s goals” (p. 2).

Leadership refers to a person’s ability to guide, modify, and direct the actions of others in such a way as to gain their cooperation in doing a job: It is the ability of a person to facilitate the problem-solving processes of others. Essentially, leadership is a process of influence; personal traits, attitudes, values, and past experience influence leadership styles and performance. According to Nahavandi [4], different leadership behaviors are effective in different situations, leading to what is referred to as situational leadership. Situational factors and the ability to motivate others influence leadership style and performance [5]. A leader must correctly evaluate situational factors ©2007 National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, ISSN 1813-3851

and select the most appropriate and effective leadership style for a given situation. Situational leadership is a popular and widely used approach that emphasizes using more than one leadership style. The theory of situational leadership has been used in several studies focusing on the manufacturing and service industries [6]. It has been applied in studies not just in the United States but in countries around the world [7]. Situational leadership is based on the interplay among the amount of guidance and direction that a leader gives, the amount or depth of relationship support or behavior that a leader provides, and the readiness level that followers exhibit in performing a specific task or achieving an objective [8]. Situational leadership is designed to help all levels of managers become more effective in their daily interactions with others.

Today’s business world is highly competitive. The only way to survive is to adapt to the needs of a rapidly changing business environment; neither an individual nor an organization can afford to ignore change. Shieh [9] indicated that customers not only demand excellent services, they also demand more services, and if a business does not supply it, its competitors will. Organizations are reshaping themselves so that they can change quickly to meet the needs of their customers. Leader must emphasize actions to undergo changes as quickly and smoothly as possible. Leaders know they cannot throw money at every problem; businesses need highly committed and flexible workers. Leader’s leadership style influence a company’s development and future. In Mainland China today, leader’s

leadership styles seem to be in a developing stage; therefore, it is necessary to clarify the question of leadership style in actual operation.

1.1 Purpose of the Research

The purpose of this study was to investigate the difference between Taiwanese executives’ leadership style and demographic characteristics in the traditional Shanghais region of Mainland China using the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ).

2. Theory Foundation and Hypothesis

2.1 Development of Leadership Theory

“Leadership is the ability to present a vision so that others want to achieve it. It requires skill in building relationship with other people and organizing resources effectively” [10]. Therefore, leadership is an important concept to leaders and organizations.

Hesselbein and Cohen [11] offered three elements of leadership. First, leadership is not just about the actions performed; it is a matter of attitude and perception. Although we all spend much of our time building our skills, leaders are defined by their character, not their learned abilities. Second, followers define a leader’s success. A leader’s job is to build a work force with high motivation and ability. A leader has to be able to give direction, ensure commitment to the team’s common task, effectively work with people both within and outside of the organization, and find subordinates who would be worth investing in with both time and attention. Finally, a leader must be able to cross boundaries among customers, the departments and sectors within an organization, other organizations, and the community at large. In crossing these boundaries, a leader must have communicated with and built a community both inside and outside of his or her organization. The world market and workplace are widely diverse, and a leader must be able to express a vision that is clear and effective.

2.2 Leadership Eras

The study of leadership is the study of change, often reflecting the mainstream view of leadership at the time; therefore, the ways of defining and explaining leadership have changed. There are four major periods in the study of leadership: the trait era, the behavior era, the contingency era, and the new era. The trait theory of leadership was developed between the late 1880s and the mid-1940s. Dessler [12] defined the trait theory of leadership as “the theory that leaders have basic identifiable traits or characteristics that contribute to their success as leaders” (p. 296). Trait theories also focused attention on determining the attributes and qualities of those extraordinary individuals who were recognized as being leaders [13]. The five traits possessed by leaders that were believed to set apart from non-leaders are intelligence, self-confidence, determination, integrity, and sociability [14]. Therefore, leaders were thought to be naturally born with specific traits that may be unique physical and psychological personal characteristics that are not possessed by others and that can differentiate leaders from followers. Ghiselli [15] reported that there are several personality traits associated with leader effectiveness. He found that the higher the person moved in an organization, the more important these traits became. Self-confidence was especially related to hierarchical position in the organization; motivation was another important trait. However, the traits theory of leadership did not apply to most people and it failed to take into account, the leadership could be learned.

Since traits of a leader could not offer enough information to explain leadership effectiveness; many researchers transferred their focus to what leaders did, how they affected groups, and how leadership effectiveness could be reached. The behavioral theory of leadership began in the mid-1940s and lasted until the mid-1970s. Its focus was on particular leadership behaviors that effective leaders used to guide followers and organizations [16]. The assumptions regarding the underpinnings of leadership traits and leadership behaviors were fundamentally different. Trait theory assumes that a leader is born, not created (i.e., a person either is a leader or is not). Behavior theory, however, assumes that a person can learn the specific behaviors that are used by effective leaders; therefore, a training program could be designed to instill those behaviors in students [17]. Newstrom and Davis [18] defined the behavior theory of leadership this way: “Successful leadership depends more on appropriate behavior, skills, and actions, and less on personal traits”. The behavioral theory of leaderships concentrated on task-oriented leadership and relationship-oriented leadership in the work place, both regarded as the best classification of leader behaviors [19]. There were three different studies that describe the behavioral theory of leadership: the Ohio State studies, University of Michigan studies, and the Managerial Grid.

Ohio State studies. In 1945, the Bureau of Business Research at Ohio State University began a series of interdisciplinary studies that focused on leadership. The research team included members from the psychology, sociology, and economics departments. The research team developed the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ) to facilitate the analysis of leadership in different situations [18]. The information obtained by the questionnaire was then subjected to factor analysis, which provided surprisingly consistent results. The analysis consistently produced the same two dimensions of leadership, termed initiating structure behavior and consideration behavior [17].

The contingency theory of leadership began in the 1960s and is still in use today. Fiedler and Chemers [11] said, “Contingency theory is a ‘leader-match’ theory, which means it tries to match leaders to appropriate situations.” It is contingent because a leader’s effectiveness hinges on whether or not the leader’s style fits in the environment.

Situational theory of leadership. According to the situational leadership model, developed in the late 1960s by Hersey and Blanchard, a leader needs to fit his or her leadership to the individual requirement of a situation. The

leader’s behavior should be contingent on the situation [21], [22]. Originally called Life Cycle theory, situational leadership theory focused on the followers, viewing the leader-follower relationship as similar to a parent-child relationship. Like parents, leaders must let go of some of their control in order for their followers to become more mature [17]. Hersey [23] said that situational leadership came out of the interaction between the guidance and direction (task behavior) the leader exhibited; the socio-emotional support (relationship behavior) the leader showed; and finally how ready the leader’s subordinates were to meet a certain goal or to perform a certain role in the organization.

Situational leadership theory viewed leadership as having two dimensions: task behavior and relationship behavior. Task behavior “. . . is defined as the extent to which the leader engages in spelling out the duties and responsibilities of an individual or group.” On the other hand, relationship behavior “. . . is defined as the extent to which the leader engages in two-way or multi-way communication” [23]. Situational leadership comprised four possible leadership styles, depending on the amount and degree of focus the leader put on relationship and task behaviors: low relationship and low task, low relationship and high task, high relationship and high task, and high relationship and low task [24]. There are four styles that could suitably be applied to a given situation, depending on the followers’ maturity levels. By combining followers’ ability and willingness, four levels of follower maturity and leadership styles are produced.

(1) The first style is the telling style, in which followers need specific guidance when they exhibit low ability and low willingness.

(2) The second style is the selling style, in which followers need direct guidance when they exhibit low ability and high willingness.

(3) The third style is the participating style, in which followers need more to be participative when they exhibit high ability and low willingness.

(4) The fourth style is the delegating style, in which followers need to be able to accept responsibility when they exhibit high ability and high willingness.

The development level of subordinates is one of the core concerns of the situational leadership model. Blanchard [21] defined development level as the level of ability and commitment that the employee exhibited and was necessary for meeting the goal in question. The employee’s ability came from his or her knowledge and competence, while willingness was made up of the employee’s commitment to the goal and his or her self-esteem [25]. A subordinate’s readiness is a measure of the willingness and ability that a subordinate has to perform a task. It was not necessarily a personal trait; rather it varied from job to job. When subordinates are unable and unwilling, they lack commitment, confidence, and/or motivation. When subordinates are not able to do the task but are willing, they lack ability but have a high motivation and make a confident effort so long as the leader provides support. When subordinates are able but unwilling they can perform to the task but do not want to exercise that ability. Finally, when subordinates are able and willing they can and want to perform the task [25]. According to the situational leadership model, effective leaders must be flexible and quick to adapt their leadership style to the current needs of their followers. An effective leader is able to notice and mark levels of readiness in followers and adapt to these varying levels. So a leader must know when and how to use the proper leadership style to support and motivate students and followers. Although there has been little research to confirm the situational leadership model, it is easily understood, well known, and used often in leadership training. The core concept of the model, that leaders must adapt their style to the abilities of their followers, is instantly appealing and popular both with those who practice it and those who

teach it.

2.3 Demographics.

In reality, there are only ambiguous definitions of a leader. For example, in the United States, leaders are defined as people who are decisive, aggressive, ambitious, intolerant of poor performance, and have strong analytical skills. Jack Welch and Andy Grove are examples of two people who have magnetized a large following because their behavior is consistent with the U.S. model of good leadership. However, in Taiwan, the popular management philosophy is teamwork, market-share objectives, and a commitment to quality.

Crainer and Dearlove [26] also mentioned that “demographic predictions in the United States suggest that the number of 35 to 44 year olds─ the traditional executive talent pool─ will fall by 15 percent between 2000 and 2015. At the same time, the number of 45 to 54-year olds—the current senior executive population─ will rise”. Baby boomers in the United States represent an aging workforce and an aging executive population because of a surplus of middle managers in the 1980s.

Moreover, the level of education is an important factor that may affect an executive. Swinyard and Bond [27] conducted a study of executives in 1967–1976 and found that subjects with a master’s of business administration (MBA) degree got their executive positions at a younger age (44 years old) than those without MBAs (47). “New CEOs through this period increasingly relied more heavily on human capital as evidenced by increasing educational levels and greater reliance on a specialized graduate degree, the Master’s of Business Administration” [28].

Furthermore, Doyle [29] noted “…the urgent need for executive development to promote both individual learning and organizational adaptation and renewal” (p. 7). Thus, executive education is seen as a strategic tool. Papadakis and Bourantas [30] found that the greater information-processing capabilities of CEOs stemmed from better education.

Another interesting point is that more recent studies including high technology industries have determined that CEOs in higher technology industries are more likely to have backgrounds in research and development, and tend to be younger than CEOs in lower technology industries [31]. Therefore, high levels of education are associated with favorable attitudes toward innovation, a high capacity for information processing, and tendency to do more analysis and searching for information.

2.5 Hypothesis of the research

There is no significant difference in leadership styles used in the companies (telling, selling, participating, and delegating) based on the demographic variables (gender, age, title, education level, years of service at the institution, and years of working in business).

3. Methodology

3.1 Population and Sampling

The population of this research was of the executives of Taiwanese investment companies doing business in Mainland China. This research focused on the Shanghai area because Shanghai is the center of the southern economic power in Mainland China with a population of 150 million people. Shanghai is the largest business and financial city, and it is one of the largest industrial cities in Mainland China [32]. Shanghai has the highest level of personal wealth and standard of living in the country. Most international investment companies select this area as their base in China. Therefore, Shanghai has become the new and largest business center in all of Asia.

According to the Taiwanese Handbook of Companies in Mainland China (Chinese National Federation of Industries, 2004), it was considered more likely that the companies listed would have headquarters in Taiwan and employ more than 500 workers. The researcher selected a sample of 140 companies and received approval to collect data from the organization and direct access to the companies’ executives. Therefore, a high level of cooperation was assured. 3.2 Measure

Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire

The Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire-Form XII was “ … developed for use in obtaining descriptions of a supervisor by the group members whom he supervises” [33]. The instrument contains two factorial-defined scales, consideration and initiating structure. This is a popular questionnaire that has been used by the military, education, and private industry. Stogdill suggested that “a number of variables operate in the differentiation of roles in social group”, including the ability to tolerate uncertainty, persuasiveness, free will of participants, prediction accuracy, the ability to integrate the way a group handles the divergent needs of its members, and workers’ orientation toward superiors.

The LBDQ–XII contains 100 items that describe specific ways in which leaders behave. It represents the fourth revision of the questionnaire and includes 12 subscales; each subscale is composed of either 5 or 10 items. A subscale is essentially defined by its component items and stands for a complex pattern of behavior.

Stogdill [33] noted that subordinates most often used the LBDQ to describe the behaviors of a supervisor. Peers and superiors can also use the questionnaire to evaluate or describe a leader with whom they were sufficiently familiar. With proper changes in instructions, leaders can use the questionnaire to describe their own behavior. Hersey et al [23] found that their concepts of task behavior and relationship behavior were similar to the initiating structure and consideration found in the Ohio State studies. These studies resulted in definitions of four kinds of leadership: (a) high initiating structure and low consideration, which was similar to the telling leadership style; (b) high initiating structure and high consideration, which was similar to the selling leadership style; (c) low initiating structure and high consideration, which was similar to the participating leadership style; and (d) low initiating structure and low consideration, which was similar to the delegating leadership style.

The leadership instrumentation and the modified version of the LBDQ XII developed by Ohio State University has been used in hundreds of studies over the past quarter century. However, most researchers continue to use only the consideration and initiating structure scales [34].

3.3 Data Collection

In the primary data collection phase, the researchers used typical survey procedures, including “…planning and design, administration, data analysis, feedback and interpretation, action planning and follow-through” [35]. Data for this research were acquired through a survey of 140 selected executives who worked in Taiwanese investment companies that do business in Shanghai. These companies had headquarters in Taiwan and employed more than 500 people. Participants were asked to complete and return the surveys within 4 weeks.

The researchers also used secondary data sources, which according to Chien [36] include “…reports, books, essays, dissertations, related periodicals, and academic journals.” The third levels of data sources were related to leadership theory and demographic including encyclopedias, dictionaries, yearbooks, and bibliographies. Data collection was conducted Sept. 16–Dec. 2, 2004. The survey instruments were distributed to 128 companies and an executive was selected in each company. However, executives at 12 companies transferred the questionnaire to their

co-workers, who are also executives in their companies. Therefore, 140 questionnaires were distributed and 87 were returned for a total response rate of 62.14%; 81 valid surveys were returned for a valid response rate of 57.85%. Fifty-three executives did not respond for a non-response rate of 37.85%.

3.4 Data Analysis

After collecting responses, the researcher scored the instruments and organized the data. The researcher then used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) edition 12.0 for Windows XP to analyze the data, utilizing various descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Means, frequencies, percentages, standard deviations, and coefficient were produced after the variables went through descriptive statistical analyses. Additionally, the researcher used a t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Scheffe test. Moreover, the researcher set the probability of statistical significance at α =.05 or α = .01. When analyzing the difference between two variables, for instance in the t-test, the p value is significant at the .05 level (p < .05).

4. Result

4.1 Reliability analysis

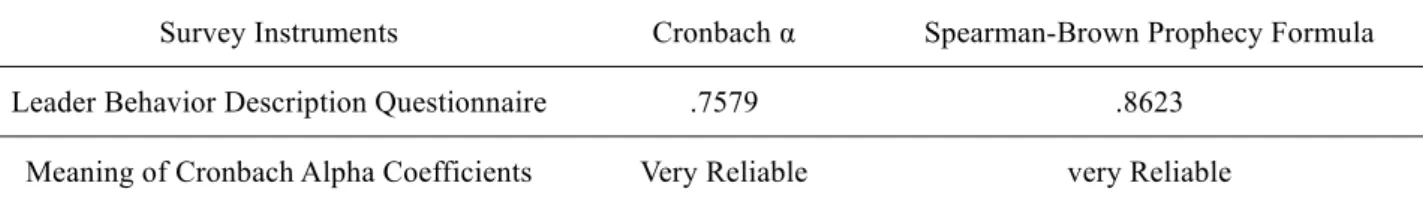

Table 1 indicates that the Cronbach alpha coefficients were .7579 in the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire. After applying the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula, the reliability coefficients range to .8623 and are regarded as proven reliable.

Table 1 Survey Instrument Reliability

Survey Instruments Cronbach α Spearman-Brown Prophecy Formula Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire .7579 .8623

Meaning of Cronbach Alpha Coefficients Very Reliable very Reliable Note. N = 81

Situational Leadership Theory considers leadership along two dimensions: task behavior (initiation of structure) and relationship behavior (consideration) [23]. Hersey stated that these two dimensions produced four styles: telling, selling, participating, and delegating, depending on the high-low levels of the two dimensions. This study showed that the dimensions of consideration and initiating structure have a reliability of 0.584 and 0.780, respectively, and are considered to be reliable.

Executives’ leadership style data were collected using the LBDQ-XII, which was divided into the consideration and initiating structure dimensions. Following the methodology of Wang [37], leadership styles were created by separating both dimensions at the mean into high and low levels. The four styles are: telling (consideration score lower than the mean, initiating structure score higher than the mean), selling (consideration score higher than the mean, initiating structure score higher than the mean), participating (consideration score higher than the mean, initiating structure lower than the mean), and delegating (consideration score lower than the mean, initiating structure lower than the mean).

4.2 Research Hypothesis

There is no significant difference in leadership styles used in the companies (telling, selling, participating, and delegating) based on the demographic variables (gender, age, title, education level, years of service at the institution, and years of working in the business).This hypothesis was tested using the t test and one-way ANOVA statistical methods. The t test was used to determine if significant differences exist in executives’ leadership style by gender. The one-way ANOVA was performed to determine if any significant differences exist in the executives’ leadership styles among age, title, level of education, years of service at the institution, and years of working in business. According to Table 2, there were no significant differences existing in the telling (t = 1.35, p >.05), selling (t = .408, p >.05), participating (t = .573, P> .05) and delegating (t = .210, p >.05) leadership styles by gender. Because the p values were greater than .05, these data provide substantial evidence that there were no significant differences between the executives’ leadership styles and gender.

Table 2 Significant Differences on Executives’ Leadership Styles by Gender

Gender Mean T P Male 83.30 Telling Female 78.00 1.35 .207 Male 83.80 Selling Female 82.00 .408 .688 Male 74.00 Participating Female 73.00 .573 .573 Male 73.90 Delegating Female 73.30 .210 .853

Note. N = 81 The mean difference is significant at the.05 level

Table 3 shows the telling, selling, and participating leadership styles were not significantly different based on the executives’ age (p > .05). However, there was a significant difference for delegating leadership style based on the executives’ age (F = 3.968, p = .021). The Scheffe test showed the differences were between the executives’ age of 40 or under (mean = 71.333); 41–50 years (mean = 73.400); 51–60 years (mean = 74.142) ; over 60 years (mean = 86).

Table 3 ANOVA for Different Dimension of Leadership Styles on the Executives’ Age

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Telling Between Group 28.375 2 14.187 .896 .442

Within Group 142.542 9 15.838

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Selling Between Group 148.910 3 49.637 1.513 .247

Within Group 557.757 17 32.809

Total 706.667 20

Participating Between Group 5.193 2 2.597 .286 .755

Within Group 172.625 19 9.086

Total 177.818 21

Delegating Between Group 170.261 3 56.754 3.962 .021

Within Group 315.124 22 14.324

Total 485.385 25

Note. N = 81 The mean difference is significant at the .05 level

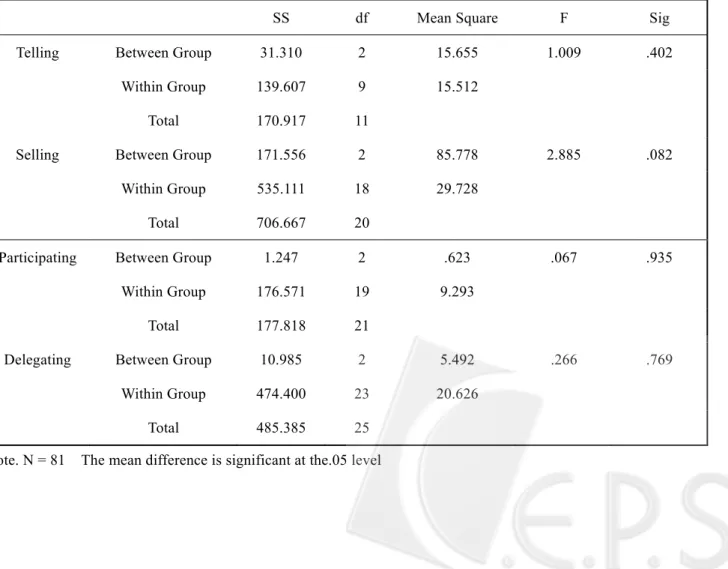

Table 4 shows the telling, selling, participating and delegating leadership styles had no significant differences based on the executives’ education level (p > .05).

Table 4 ANOVA for Different Dimension of Leadership Styles on the Executives’ Education Level

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Telling Between Group 31.310 2 15.655 1.009 .402

Within Group 139.607 9 15.512

Total 170.917 11

Selling Between Group 171.556 2 85.778 2.885 .082

Within Group 535.111 18 29.728

Total 706.667 20

Participating Between Group 1.247 2 .623 .067 .935

Within Group 176.571 19 9.293

Total 177.818 21

Delegating Between Group 10.985 2 5.492 .266 .769

Within Group 474.400 23 20.626

Total 485.385 25

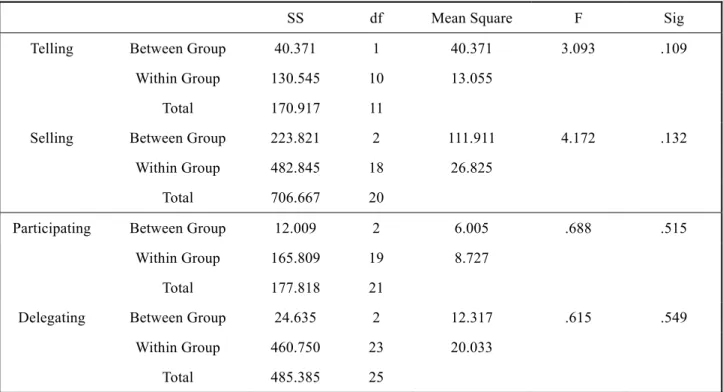

Table 5 show the telling, selling, participating, and delegating leadership styles were not significantly related based on the executives’ title (p > .05).

Table 5 ANOVA for Different Dimension of Leadership Styles on the Executives’ Title

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Telling Between Group 40.371 1 40.371 3.093 .109

Within Group 130.545 10 13.055

Total 170.917 11

Selling Between Group 223.821 2 111.911 4.172 .132

Within Group 482.845 18 26.825

Total 706.667 20

Participating Between Group 12.009 2 6.005 .688 .515

Within Group 165.809 19 8.727

Total 177.818 21

Delegating Between Group 24.635 2 12.317 .615 .549

Within Group 460.750 23 20.033

Total 485.385 25

Note. N = 81 The mean difference is significant at the .05 level

Table 6 presents the results of the analysis of the different leadership styles based on the executives’ years of working in the business. The telling, selling, and participating leadership styles were not significantly related to the executives’ years of working in business (p > .05). However, the delegating leadership style was significantly related to the executives’ years of working in the business (F = 3.134, p = . 030). The Scheffe test showed that for the delegating leadership style, the differences were between the executives’ years of working in business of 11–15 years (mean = 71.666); 10 or under years (mean = 72.500) ; 16–20 years (mean = 73.100) ; 26–30 years (mean = 76.750) ; over 30 years (mean =86).

Table 6 ANOVA for Different Dimension of Leadership Styles on the Executives’ Years of Working in Business

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Telling Between Group 39.250 5 7.850 .358 .860

Within Group 131.667 6 21.944

Total 170.917 11

Selling Between Group 194.786 5 38.957 1.142 .381

Within Group 511.881 15 34.125

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Participating Between Group 23.577 5 4.715 .489 .780

Within Group 154.242 16 9.640

Total 177.818 21

Delegating Between Group 213.235 5 42.647 3.134 .030

Within Group 272.150 20 13.607

Total 485.385 25

Note. N = 81 The mean difference is significant at the.05 level

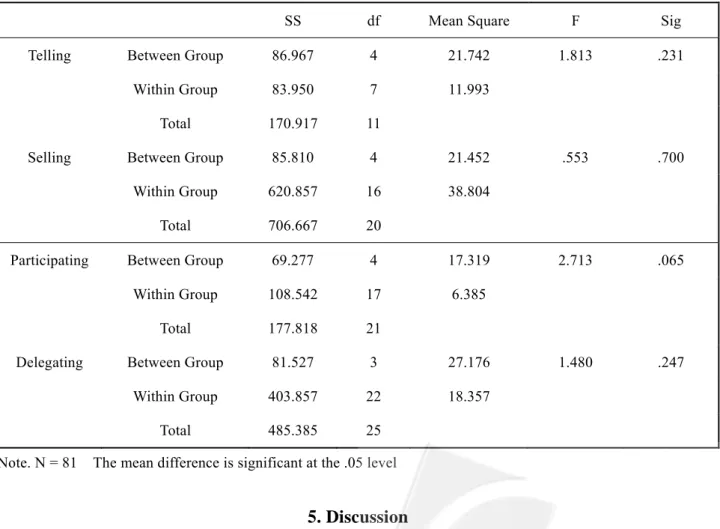

Table 7 show the telling, selling, participating, and delegating leadership styles were not significantly related based on the executives’ years of service at institution (p > .05).

Table 7 ANOVA for Different Dimension of Leadership Styles on the Executives’ Years of Service at Institution

SS df Mean Square F Sig

Telling Between Group 86.967 4 21.742 1.813 .231

Within Group 83.950 7 11.993

Total 170.917 11

Selling Between Group 85.810 4 21.452 .553 .700

Within Group 620.857 16 38.804

Total 706.667 20

Participating Between Group 69.277 4 17.319 2.713 .065

Within Group 108.542 17 6.385

Total 177.818 21

Delegating Between Group 81.527 3 27.176 1.480 .247

Within Group 403.857 22 18.357

Total 485.385 25

Note. N = 81 The mean difference is significant at the .05 level

5. Discussion

5.1 Gender

Many studies discussing executives’ gender issues in the United States, including Lyness and Thompson’s investigation [38] of both the position and compensation of female executives compared with male executives. They

found that although there were no significant differences in base salaries or bonuses between male and female executives, male executives had more authority than did female executives.

Moreover, women often find themselves in stereotypically feminine areas (i.e., education, health, social services) and in less powerful positions than their male colleagues when they advance to managerial and higher level positions [39]. Therefore, female executives, faced with a lack of power and status in their positions, are forced to adopt a more deferential leadership style in order to get the cooperation that they require [40]. According to research done at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, the number of female executives in the United States is now lower than it was 10 years ago (Crainer & Dearlove, 1999). In 1987, there were 11 female directors at Fortune 500 companies; by 1997, there were just eight. The number of women CEOs in these companies was two in 1987 and remains the same a decade later [26].

There was no significant difference in leadership styles based on gender. In the sample included 72 men and only 9 women. Therefore, there was not enough of a balance between the genders to test any significant difference between men and women. The Taiwanese investment companies may have been deeply influenced by Confucianism, which posits that men have more ability to lead than women. According to Redding [41], two of Confucius’ “Five Cardinal Relations” involved the subordination of the younger brother to the elder, and the wife to the husband. These basic rules permeate Chinese social life, even in modernized societies like Singapore and Hong Kong. The authority of male is socially ingrained.

5.2 Delegating leadership style based on the age and executives’ years of working in the business

In the hypothesis, there was a significant difference among executives’ delegating leadership style depending on their age. Through the multiple comparisons, the results show that the executives older than age 60 preferred to use a delegating leadership style. In the hypothesis, there was a significant difference among executives’ delegating leadership style depending on their years of working in business. Through the multiple comparisons, the results show that the executives with more than 30 years of working in business preferred to use a delegating leadership style. With that amount of experience, the executives are most likely to have in-group managers. Those managers will usually have a tenure of 15 to 20 years. Therefore, the managers receive a great deal of trust from the executives, and their long-time managers are like family, with the managers giving the executives their loyalty and devotion in return.

The age and number of years of working in the business were important factors that influenced the executives’ leadership styles. Hambrick and Mason said that a manager’s personal experiences and values can be concluded from perceptible demographic categories, such as age and year of experience. A top business executive can expect members of a management team to act as a cohesive unit. Over time a self-selection process becomes evident by which only those who embrace certain norms and perspective are willing or allowed to stay in an organization [42]. The longer an executive is at a company, the more pronounced his or her leadership style becomes. Allen and Cohen [43] found that background and work experiences in an organization shape the ways that people process information. Katz [44] pointed out that those managers are likely to depend increasingly on their past experiences and routine information sources rather than on new information with growing organizational experience.

6. Conclusion

In general, the executives usually had two or three leadership styles in different situations; there was no one best leadership style. Executives can effectively use a variety of leadership styles, depending on the competence and

commitment of the individual employee. Moreover, research suggests that homogeneity on length of time of leading in the organization can lead to similar interpretation of events ([43], [45]) and a common vocabulary [46], and can enhance communication among group members [47].

Many leadership practitioners and scholars [48] have proposed that followers need leadership to inspire them and enable them to enact revolutionary change in today’s organizations. Situational Leadership style is intuitively appealing and popular with practicing managers in such areas as business, research and development, communications, project management, health care, and education [49].

Reference

[1] Yi, Y., Marketing in East Asia: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Psychology & Marketing (1986-1998), 15, 6, 1998.

[2] Zhang, Q., Changing economy, changing market, A sociolinguistics study of Chinese yuppies. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, California, 2001.

[3] Erven, B. L., Becoming an effective leader through situational leadership. Columbus, OH: Department of Agricultural, Environment, and Development Economics, Ohio State University Extension, 2001.

[4] Nahavandi, A., The art and science of leadership (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2003. [5] Yeakey, G. W., Situational leadership. Military Review, 82 (January- February), 72–82, 2002.

[6] Benson, F., The one right way doesn’t work with leadership either. The Journal for Quality and Participation 17(4), 86–90, 1994.

[7] Avery, G. C., Situational leadership preferences in Australia: Congruity, flexibility and effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 22(1), 11–21, 2001.

[8] Lowell, R., Situational leadership T+D. Alexandria, 5(4), 80-81, 2003.

[9] Shieh, T. H. The leader condition and the leadership potency relations research - take middle some chain-like retail trade as an example. Masterly Dissertation, The Chung-Chang University, Taiwan, 2002.

[10] O’Connor, C., Successful leadership. New York: Barron’s Educational Series, 1997.

[11] Hesselbein, F., & Cohen, P. M. (Eds.).. Leader to leader: Enduring insights on leadership from the Drucker Foundation's award-winning journal. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

[12] Dessler, G., Management (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. [13] Bingham, W. V., The psychological foundations of management. New York: Shaw, 1927. [14] Northouse, P. G., Leadership: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001.

[15] Ghiselli, E. E., The validity of management traits in relation to occupational level. Personnel Psychology, 16, 109–113, 1963. [16] Morgan, L. E., The perceived leader behavior of academic deans and its relationship to subordinate job satisfaction. Doctoral

dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin, 1984.

[17] Robbins, S. P. Organizational behavior (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2001. [18] Newstrom, J. W. & Davis, K., Organizational Behavior. (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

[19] Yukl, G., Gordon, A., & Taber, T., A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9, 15–39, 2002.

[20] Fiedler, F. E., & Chemers, M. M., Leadership and effective management. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Co, 1974. [21] Blanchard, K. H., SLII: A situational approach to managing people, Escondido, CA: Blanchard Training and Development,

1985.

[22] Blanchard, K. H., Zigarmi, D., & Nelson, R., Situational leadership after 25 years: A retrospective. Journal of Leadership Studies, 1(1), 22–36, 1993.

[23] Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Johnson, D. E., Management of organizational behavior: Leading human resource (8th ed.).Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall,(2001.

[24] Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Johnson, D. E., Management of organizational behavior: Utilizing human resource (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1996.

[25] Hersey, P., The situational leader (4th ed.). Escondido, CA: Center for Leadership Studies, 1992. [26] Crainer, S. & Dearlove, D., Death of executive talent. Management Review, 88(7), 16–24, 1999. [27] Swinyard, A. W. & Bond, F. A., Who gets promoted? Harvard Business Review. 19 (1), 5–15, 1980.

[28] Keiser. J. D., Chief Executives from 1960–1989: A trend toward professionalization. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10 (3), 52–69, 2004.

[29] Doyle, M. Organizational transformation and renewal: A case for reframing management development? Personnel Review, 24(6), 6–19, 1995.

[30] Papadakis, V. & Bourantas, D., The chief executive officer as corporate champion of technological innovation: An empirical investigation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 10 (1), 89–110, 1998.

[31] Hambrick, D. C., Black, S., & Fredrickson, J. W., Executive leadership of the high technology firm: What is special about it? In L. R. Gomez-Meija, & M. W. Lawless (Eds.), Top management and effective leadership in high technology (pp. 255–271). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1992.

[32] Daizen, K., The China impact, Taipei, 2002.

[33] Stogdill, R. M., Manual for the leader behavior description questionnaire– Form XII. Columbus, OH: Bureau of Business Research, Ohio State University, 1963.

[35] Kraut, A., Organizational surveys: Tool for assessment and change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996.

[36] Chien, C. S., Leadership style and employees’ organizational commitment: An exploration study of managers and employees of Hsin-Zhu Science Park. Doctoral dissertation, The University of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio, TX. 2003.

[37] Wang, G. L., A study of the government leader’s leadership behavior in Kaohsing city hall. Masterly Dissertation, The Chung-Shan University, Taiwan, 2002.

[38] Lyness, K. S. & Thompson, D. E., Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 359–375, 1997.

[39] Burress, J. H., & Zucca, L. J., The gender equity gap in top corporate executive positions. Mid - American Journal of Business. 19, 55–63, 2004.

[40] Kanter, R. M., Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic, 1977.

[41] Redding, S. G., The spirit of Chinese capitalism. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 1990.

[42] Pfeffer, J., Organizational demography. Research in Organizational Behavior, 5, (1983), 299–357.

[43] Allen, T., & Cohen, S., Information flow in research and development laboratories. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14 (1), 12-19, 1969.

[44] Katz, D., The effects of group longevity on project communication and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27 (1), 81-104, 1982.

[45] Lawrence, P. & Lorsch, J.,Leadership and organizational performance: A study of large corporations. American Sociological Review, 37 (1), 117–130, 1967.

[46] Rhodes, R., Theory and methods in British public administration: the view from political science. Political Studies, 39 (5), 533–554, 1991.

[47] March, J. G. & Simon, H. A., Organizations. New York: Wiley, 1958.

[48] Bass, M. B., Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press, 1985. [49] Yukl, G. A., Leadership in organizations (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989.