The Evidence from Collateralized Shares

ABSTRACT

This paper indicates that there is an inverse relationship between collateralized shares and firm performance. Furthermore when the entire sample is divided into a sub-sample of conglomerate firms and a sub-sample of non-conglomerate firms, we show that this inverse relationship exists only in conglomerate firms. These findings imply that agency problems resulting from shares used as collateral by boards of directors are more serious in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms. Moreover, we provide evidence that monitoring by institutional investors, creditors and dividend policy can effectively reduce the agency problems of shares used as collateral and thus can improve firm performance. Empirical findings indicate that institutional holdings, debt ratio and dividend payout ratio can mitigate the negative effect of agency problems on firm performance. In addition, monitoring mechanisms are more beneficial for conglomerate firms than for non-conglomerate firms.

I. Introduction

Traditional agency theory assumes that ownership of a firm is well diversified among shareholders and that managers of the firm have control over it, so the agency problem derives from the conflicts between shareholders and managers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). However, several studies have criticized the validity of the assumption of well-diversified ownership structure, such as Shleifer and Vishny (1986), Morck et al. (1998), Claessens et al. (1999) and La Porta et al. (1999, 2000a). Of these, La Porta et al. (1999) examined the largest firms in 27 high-income economy identities and found that, except for the economies with solid protection for the shareholders, few firms were widely held, with most typically being held by controlling families. Furthermore, the so-called controlling shareholders have controlling rights over cash flow rights through pyramids or participation in corporate management. La Porta et al. also argued that the controlling shareholders are generally not monitored by other large shareholders. Thus, in an economy with controlling shareholders, another kind of agency problem derives from the conflicts between the outside shareholders and the controlling shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). La Porta et al. (1999) suggested that the expropriation of the minority shareholders’ by the controlling shareholder should not be over-emphasized and deserves investors’ attention.

The ownership structure of the firms in Taiwan is that controlling shareholders, as mentioned in La Porta et al. (1999). In addition, Yeh and Lee (2001) pointed out that 76% of the firms listed in Taiwan are controlled by individual families, and that 66.45% of the boards of directors are totally controlled by individual families. Therefore, the agency problem resulting from the controlling shareholders cannot be over-emphasized. Previous studies examining the economy with controlling shareholders have typically focused on how controlling shareholders affect the firm value (or firm performance). The determinants of firm performance related to controlling shareholders include the ownership of board of directors, the proportion of board of directors’ shares collateralized, whether or not the controlling shareholders belong to a family, the size of the board, and the ownership level of the family owning most of the shares. This paper extend that issue to investigate how the agency problem resulting from the collateralized shares by controlling shareholders (or directors) influences firm performance. In addition, from the prospective of corporate

governance, it analyzes whether the current monitoring mechanisms reduce the agency problems.

Claessens et al. (2002) examined the deviation of ownership and control rights in nine East Asia countries. They found that the controlling shareholders have control rights over cash flow rights throughout pyramids1 and crossholding, and that deviations of ownership and control rights are more significant in family-controlled and small firms. For example, according to the definition of La Porta et al. (1999) and Claessens et al. (2000), if a single family owns 11% of outstanding shares of firm A, and firm A owns 21% of outstanding shares of firm B, assuming that A and B do not cross-hold each other, we say the family owns 2% of B’s cash flow rights (the product of 2 ownerships), and it also owns 11% of the control rights of firm B through a pyramid structure. This results in a separation of ownership rights from control right.

La Porta et al. (1999) pointed out that deviation of control rights and cash flow rights provide the controlling shareholders incentive to expropriate the outside shareholders to benefit themselves. Claessen et al. (1999) examined the individual effects of cash flow rights and control rights owned by controlling shareholders on market valuation for Asian public firms. They found that, for those firms, the more the cash flow rights owned by controlling shareholder, the higher the share price is. This is consistent with Jensen and Meckling (1976). However, they also found that concentration of control rights is negatively related to share price, consistent with Morck et al. (1998) and Shleifer and Vishny (1997). In addition, Classens et al. (1999) also found that deviation of cash flow and control right would decrease the firm value, indicating that controlling shareholders expropriate minority shareholders. Shares collateralized by boards of directors or other large shareholders should be considered as personal conducts and should be irrelevant to the operations of the firm under the separation of ownership and control. However, the separation of ownership and control does not apply to firms in Taiwan and leads to a connection between personal collateralized shares and firm performance. The deviation of control rights and cash flow rights owned by controlling shareholders is exacerbated by collateralized shares, providing the controlling shareholders stronger incentive to expropriate minority shareholders. Assuming that a controlling shareholder owns

1

50% of the outstanding shares, the nominal ownership (cash flow right) is 50%. Once the controlling shareholder has collateralized half of his shares for funds, his real ownership is only 25%, making the deviation of control right and cash flow right more significant than that without collateralized shares. Thus, the agency problem between controlling shareholders and outside shareholders more severe when there are collateralized shares than when there is no shares collateralized for funds.

According to statistics from the securities exchange, we collateralized shares in of board of directors are fairly common in Taiwan. Up to November 2000, only 28% (147 firms) of the listed firms did not have shares collateralized by their boards of directors. There are 312 firms (34% of the listed firms) with a collateralized share ratio (defined as the number of shares collateralized by the board of directors divided by the total number of shares owned by the board of directors) lower than 20%. There are 110 firms (21%) with collateralized share ratio between 20% and 50%; 103 firms (20%) with collateralized share ratio higher than 50%; 21 firms (4%) with collateralized share ratio higher than 90%; 17 firms (3.24%) with collateralized share ratio between 80% and 90%; 16 firms (3.05%) with collateralized share ratio between 70% and 80%. Moreover, 40% of the stocks traded in the over-the-counter market experience shares collateralized by board of directors.

Even though collateralized shares held by boards of directors are very popular in Taiwan, there has been little research to examine the relationship between that phenomenon and performance of these firms’ shares of board of directors. This paper examines the effect of agency costs due to collateralized shares on the firm performance, and further examines how to alleviate the agency costs of collateralized shares through corporate control mechanisms. Bushman and Smith (2001) defined corporate control mechanisms as those means by which managers and controlling shareholders are disciplined to act in the investors’ interest. So far, in Taiwan there is no legal regulation on shares collateralized by directors, and the government simply urges the investors to pay attention to the level of collateralized shares held by the directors to protect their own interest. Hence, investors are not protected by any legal regulation on collateralized shares and are at the risk of being expropriated by the controlling shareholders. Lacking legal regulation on collateralized shares of board of directors, it is important to investigate how to mitigate the agency cost of

collateralized shares through monitoring mechanisms from the capital markets. Levine (1977) showed that if investors are not sure about their safety by expropriation by the management, they will not invest money in those firms. The alleviation of agency cost of collateralized shares will increase the willingness of investors to invest in the capital markets. Both the World Bank (1999) and OECD (1999) have point out that boards of directors are the core of corporate governance. However, monitoring of these boards is weak in Taiwan, so monitoring by capital markets is especially important in Taiwan. This paper focuses on the efficiency of monitoring by capital markets such as monitoring by institutional investors to reduce the agency cost of collateralized shares held by directors.

In this paper, we examine whether any of three kinds of monitoring mechanisms from capital markets─ institutional investors, creditors and dividend yield─can efficiently reduce the agency cost of collateralized shares. Shleifer and Vishny (1986) as well as Agrawal and Mandelker (1990) support the monitoring function from the institutional investors. Faced with agency problems, the institutional investors can either monitor the firm or sell out their holdings. This paper examines the role of institutional investors as a monitoring mechanism and how these institutional investors can reduce the agency cost of collateralized shares. Jensen (1986) argues that debt can be considered a good way to alleviate the agency cost. However, the effect of debt’s reducing agency cost is influenced by other monitoring mechanisms. This paper argues that because currently no legal regulation exists to efficiently reduce the agency cost of collateralized shares, debt is an important factor to monitor the behavior of directors in terms of collateralized shares.

Finally, we also examine the role of dividends on reducing the agency cost of shares collateralized by directors. La Porta et al. (2000b) showed that faced with agency problems due to insiders, dividends can protect the benefit of outside investors. The minority shareholders will ask the firm to pay cash dividends to reduce related agency cost of free cash flow. Thus, agency cost is reduced by paying dividends. La Porta et al. also found that the stronger the power of the minority shareholders, the more cash they receive from the firm. This paper also investigates whether the paid dividends can efficiently reduce the agency cost of collateralized shares.

II. Related Literature

2.1 Conflicts between controlling shareholders (or boards of directors) and outside shareholders

Contrary to the separation of ownership and control, which implies that the agency cost of conflict between shareholders and managers, the existence of controlling shareholders implies that there is agency cost of conflicts between controlling shareholders and outside shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Morck et al., 1988; and La Porta et al., 2000a). La Porta et al. (1999) examined the major economies in the world and found that most of the firms in the world are controlled by single families, except for firms in the U.S. The controlling shareholders or controlling families gain control through pyramidal structures and have more control rights than cash flow rights. The deviation of control rights and cash flow rights induces the controlling shareholders to expropriate the outside shareholders. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) show that when there are pyramidal structures, management would draw off cash from the firm, expropriating the outside shareholders not only through free cash flow but also through transfer pricing system. Thus, management could establish an independent firm under a separate name and sell products at lower prices to that firm. In Taiwan, Lee (2001) also found that the greater the deviation of control rights and cash flow rights, the greater the incentive for the controlling shareholders to expropriate outside shareholders, and also the higher the frequencies of stock transactions, non-operations income and non-operations sales among the controlling shareholders and their relative parties.

Yeh and Lee (2001) pointed out that 76% of the listed firms in Taiwan are controlled by family shareholders and 66.45% of the boards of the listed firms are totally controlled by family shareholders. We can consider the role of directors from two different perspectives: monitoring and expropriation. Fama (1980) and Williamson (1988) show that the board structure is influential on functions of governance. In Taiwan, there are controlling shareholders (or families) in most of the firms, and often the board of directors is controlled by family shareholders (Yeh and Lee, 2001). Hence, it is doubtful whether the board can monitor the management efficiently. When the board of directors has control over the managers, managers will act in the interest of the board of directors rather than in the interest of

outside shareholders’. Hence, we should consider the possible expropriation by directors of the minority shareholders.

In Taiwan, boards do not efficiently monitor their firms, and in some cases the board even creates another source of agency problems when the board is controlled by one family. During 1998 and 1999, many firms were in financial distress, which could be partly attributed to the Asian financial crisis. However, some of the causes of this financial distress can also be attributed to expropriations by the board. For example, the boards of Tung Lung Metal Industrial Co. and Ban Yu Paper Mill Co., Ltd. sold the assets of these firms to other firms at with extremely low prices. Similarly, the controlling shareholders of Victor Taichung Machinery Works Co., Ltd. and Chinese Automobile Co., Ltd. used the capital of these firms to support their stock prices, leading to big losses of both firms. Chiou et al. (2002) argued that the higher the collateralized share ratio, the higher the financial leverage of the firms and the higher the possibility of being in distress.

As to the shares held and collateralized for loan by the board of directors, we find that collateralized shares are quite common in Taiwan. However, there has been little research examining the relationship between collateralized shares of board of directors and performance of the firm. So far, research on collateralized shares has generally focused on the relationship between financial distress and collateralized shares during the Asian financial crisis. Chiou et al. (2002) pointed out that collateralization of shares by the board of directors raises the possibility of being in distress. Chen and Hu (2001) show that for the firms with investment opportunities, collateralized shares increase the risk of the firm. In good economic times, collateralized shares of controlling shareholders are positively related to firm performance, whereas collateralized shares of controlling shareholders are negatively related to firm performance in bad economic times.

2.2 Corporate control mechanisms

Corporate control mechanisms are means by which managers and controlling shareholders are disciplined to act in the investors’ interest. Control mechanisms include both internal mechanisms such as managerial incentive plans, director monitoring and internal labor market; and external mechanisms such as outside shareholder or creditor monitoring, the market for corporate control, competition in

the product market, the external managerial labor market, and securities laws that protect outside investors against expropriation by corporate insiders (Bushman and Smith, 2001). Because there is no legal regulation on collateralized shares of controlling shareholders, the monitoring of collateralized shares by the capital markets is even more important. In this paper, we examine three monitoring mechanisms of collateralized shares: institutional investors, creditors and dividend policy.

2.2.1 Role of debt in monitoring agency problems

Under the separation of ownership and control, agency problems result from the separation of decision-making and risk-sharing. Jensen and Meckling (1976) argued that managers have an incentive to consume excessive perquisites and/or other opportunistic benefits since they would gain the entire benefit of such activities but bear less cost related to the entire benefit. Jensen and Meckling considered this as the agency cost of equity.

Literature on agency theory suggests that debt may also be applied to reduce agency costs. The empirical evidence generally supports the agency model implications for the firm’s use of debt. Grossman and Hart (1982) argued that the existence of debt forces managers to consume fewer perquisites and become more efficient and productive owing to the increasing probability of bankruptcy and the loss of control and reputation. The agency theory shows that debt reduces agency costs of the firm, and thus increases the value of the firm. Jensen (1986) similarly argued that debt reduces the managers’ control right over cash flow and induces the managers to engage in non-optimal investments because debt implies the firm’s guarantee of making periodic payments of interest and principal.

2.2.2 Institutional investors as monitoring agents

From a theoretical point of view, Shleifer and Vishny (1986) argued that large shareholders have an incentive to monitor managers for their own interests. They regard the existence of large shareholders as a monitoring mechanism on the behaviors of managers and argue that the presence of large stockholders is good for the value of the firm. Agrawal and Mandelker (1990), Bathala et al. (1994) and Seetharaman et al. (2001) also supported the claim that institutional investors play an important role in monitoring the activities of management and in reducing agency

problems.

2.2.3 The role of dividends in an agency context

Modigliani and Miller (1961) argued that dividend policy is irrelevant to the value of the firm, leading researchers to be curious about the purposes of dividend polices. A typical explanation for paying dividends is that firms can signal their future cash flow by their dividend policies (for example, see Miller and Rock, 1985; and Ambarish et al., 1987). However, DeAngelo et al. (1996) showed that current dividend changes have no predictive power on firms’ future earnings growth.

On the other hand, Jensen (1986), Fluck (1999) and Gomes (2000) argued that dividend policies alleviate the agency problems between insiders and outside shareholders. If earnings are retained in the firms rather than being paid out to shareholders, the insiders will have more fund sources for personal use or for unprofitable projects that provide extra benefits for the insiders. Consequently, outside shareholders prefer dividends to retained earnings. The key point is that free cash flow leads to its diversion or waste, which is hazardous to outside shareholders’ interest.

III. Hypotheses and empirical design

This section investigates the relationship between firm performance and collateralized shares of controlling shareholders and how the governance roles of institutions, creditors and dividend yields reduce the agent conflicts of collateralized shares on firm performance.

3.1 Firm performance and collateralized shares

First we examine the firm performance and collateralized shares. Since collateralized shares exacerbate the deviation of cash flow right and control right held by controlling shareholders, inducing more severe agency problem between controlling shareholders and outside shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; La Porta et al., 1998; Claessens et al., 2000), we therefore expected collateralized shares to have a negative impact on firm performance. In addition, due to the less transparent operations and payment of cash flow for conglomerate firms, we expect that the agency problem related to collateralized shares is more severe in

conglomerate firms than non-conglomerate firms.

The related research indicates that deviation of ownership and control rights provides the controlling shareholders incentives to expropriate the minority shareholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; La Porta et al., 1998; Claessens et al., 2000). For example, Claessen et al. (1999) find that deviation of cash flow rights and control rights decreases firm value. The price discount provides the evidence that controlling shareholders expropriate minority interest. Since the shares collateralized by controlling shareholders decrease the real ownership of controlling shareholders, the agency problem due to deviation of control rights and cash flow rights is more severe when there are collateralized shares than without them. Thus, we expect that collateralized shares will harm the firm performance.

This section also re-examines the relationship between firm performance and collateralized shares based on the following conceptual model:

i i

i f AGENCY CONFLICT OtherControlVariables

PERF

FIRM_ ( _ , )

where FIRM_PERFi is a measure of performance for firm i, and AGENCY_

CONFLICT is a measure of the agency conflict due to collateralized shares. Firm performance consists of accounting performance and financial performance. Accounting performance is measured by ROE or ROA, whereas financial performance is measured by Tobin’s Q. We expect that the higher the agency cost due to collateralized shares of board of directors, the lower the firm’s performance during bear markets.

Second, we test whether the agency problem related to collateralized shares is more severe in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms. A typical conglomerate consists of many diversified and legally independent affiliate entities, which may be controlled by a controlling family. The agency problem related to conglomerates is that the objective of their managers is not shareholder values maximization, but rather controlling family values maximization. Controlling shareholders (or chairman) control the overall business group through the office of the chairman office, which coordinates the internal resources to achieve most economic transaction cost. This office dominates important decisions and surpasses board of

directors in individual affiliated firms.

The governance issue related to conglomerates arises when the power of the controlling family exceeds the individual board of directors in the conglomerate. The controlling family not only sets long-term financial objective for each affiliated firm, but also is involved in daily operation through the chairman’s office. Since the board members are often inside directors appointed by the controlling family, the individual board of directors plays little role in corporate governance. If they lack monitoring by the market, the controlling family tends to ignore the voice of outside shareholders. Claessens et al. (1999) found that the extent of separation of management and ownership is negatively related to firm performance. Faccio et al. (2001) pointed out the separation of management and ownership is negatively related to dividend distribution, indicating that the benefits of outside shareholders in pyramids is systematically expropriated.

Furthermore, since it is much easier for the controlling shareholders to transfer funds within conglomerate firms (such as related-firm transactions and internal transfer pricing to switch income from a high-performance firm to low-performance firms), we argue that agency problems due to collateralized shares are more severe in conglomerate firms. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: There is an inverse relation between firm performance and the level of shares collateralized by controlling shareholders. The inverse relation is more severe in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms.

3.2 The effect of monitoring mechanisms on reducing the agency problems induced by collateralized shares

Accounting to Bushman and Smith (2001), corporate control mechanisms are the means to direct the manager to act for the benefit of investors. Corporate control mechanisms include internal ones, such as manager’s incentive program, monitoring from board of directors; and external mechanisms, such as monitoring from outside shareholders and bondholders, the market for corporate control, product market competition, labor market pressure, and security regulation provided to avoid the expropriation of outside investors by insiders.

Traditional accounting research in governance has focused on how to use accounting information to reinforce the function of governance. In the U.S., since

the separation of ownership and control is popular, most research has focused on how to accommodate accounting information into reward schemes that can induce managers to act in shareholders’ interest (Bushman and Indjejikian, 1993; Feltham and Xie, 1994; Ittner et al., 1997). Accounting information can be considered as the monitoring mechanism with lowest cost. However, Kao and Chiou (2002) have already shown that collateralized shares would reduce the value relevance of accounting information. Therefore, the governance role of accounting information is doubtful. Bushman et al. (2000) showed that when accounting information does not monitor the management efficiently, demand for costly monitoring mechanisms such as boards of directors and “large” investors become stronger. According to Kao and Chiou (2002), we find that accounting information loses value and becomes less relevant when there are agency problems of collateralized shares. Therefore, we need substitutive monitoring mechanisms to reduce the agency costs of collateralized shares. Due to the limits of the information provided by financial accounting reports, the existence of collateralized shares leads to the use of more costly monitoring mechanisms and/or constraints of directors’ behaviors. Since the governance role of board of directors has been criticized, the monitoring of collateralized shares from the capital markets is more important. In this paper, we examine the roles of three monitoring mechanisms for collateralized shares: institutional investors, creditors and dividend policy. The conceptual model of monitoring mechanism on agency cost of collateralized shares is as follows:

i ij j n j i i i X MONITORING CONFLICT AGENCY t cons PERF FIRM * ) ( ) * _ ( * tan _ , 2 1

where, FIRM_PERFi is a measure of firm performance for firm i; AGENCY_

CONFLICT is a measure of the agency conflict due to collateralized shares; and MONITORING is a measure of the corporate control mechanisms. The variable (AGENCY_CONFLICT* MONITORING) is included in the empirical specification to examine whether specified monitoring mechanisms interact with agency conflict or has explanatory power as a main effect. The slope, 1, captures the interaction

between the relative magnitude of the agency conflict in firm i the monitoring mechanisms in firm i, and it also reflects the effects of high corporate control on firm performance through the reduction of agency problems due to collateralized shares held by controlling shareholders. The channel through which we expect monitoring

mechanisms to enhance economic performance is its governance role. The governance roles of monitoring mechanisms enhance economic performance indirectly by lowering the risk premium demanded by investors to compensate for the risk of loss from expropriation by opportunistic managers.

We use Tobin’s Q to proxy for the firm’s performance and use the ratio of share collateralized by directors as a proxy for the agency problems between outside investors and controlling shareholders (i.e., investors’ risk of expropriation by insiders). We observe three monitoring mechanisms: institutional investors, debt/asset ratio and dividend yields. In conclusion, we argue that the negative relation between firm performance and the level of share collateralized by controlling shareholders is weaker for firms with high levels of mechanisms to reduce agency-conflicts than for firms with less of these mechanisms.

3.2.1. Governance roles of institutional investors to reduce the agent conflicts induced from collateralized shares on firm performance.

The empirical results reported in both Bushman et al. (2000) and La Porta et al. (1998) are consistent with the predicted negative relation between the information provided by financial accounting systems and the demand for costly monitoring by large shareholders. In other words, the demands on institutional investors to undertake costly information acquisition and processing activities are likely to be high in settings where the information provided by the financial accounting system is relatively low. In the first part of this paper, we find that collateralized shares reduce the value relevance of accounting information and thus reduces the monitoring effect from accounting information. Under this scenario, capital markets would respect the monitoring effect from institutional investors. Most research supports the view that large institutional investors are able to monitor the activities of management and limit agency problems (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Agrawal and Mandelker, 1990 and Bathala et al., 1994). Nevertheless, the importance of monitoring by institutional investors depends on the proportion of shares owned by these institutional investors. The more shares owned by institutional investors, the more efficient the monitoring from institutional investors. If the institutional investors find that the invested stocks have high agency costs or are performing poorly, they might reduce their holdings or sell out the shares. On the other hand, if the institutional investors own many shares, they will put more efforts in monitoring the firms. In Taiwan, although individual investors are the majority in stock markets, the holdings of institutional investors are

continually increasing. We argue that institutional investors play an important role in reducing the agency costs of collateralized shares. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2A: The negative relation between firm performance and the level of shares collateralized by controlling shareholders is weaker for firms with a high percentage of outstanding shares held by institutions than for firms with a low percentage these shares.

3.2.2.The governance roles of creditors to reduce the agent conflicts induced from collateralized shares on firm performance

The agency literature suggests that debt may also be useful in reducing agency problems (Jensen, 1986), and the empirical evidence is generally favorable to agency model implications for the use of debt in the firm. Jensen (1986) argued that, because debt “bonds” the firm to make periodic payments of interest and principal, it reduces the control of managers over the firm’s cash flow and the incentive to engage in non-optimal activities.

Hypothesis 2B: The negative relation between firm performance and the level of share collateralized by controlling shareholders is weaker for firms with a high debt ratio than for those with a low debt ratio.

3.2.3.The governance roles of dividend policy to reduce the agent conflicts induced from collateralized shares on firm performance

Jensen (1986), Fluck (1999) and Gomes (2000) raised the idea that dividend policies mitigate agency problems between the inside and the outside shareholders. Profits, if not paid out to shareholders, may be diverted by the insiders for personal use or for unprofitable projects that provide private benefits for the insiders. As a consequence, paying out dividends may reduce the risk of expropriation of retained earnings by insiders. We propose two measures for dividend yield: one is the cash dividend yield; the other is a dividend yield consisting of both cash dividends and stock dividends. Overall, the higher the dividends paid, the lower the retained earnings which can be expropriated by the controlling shareholders. Hypotheses 2C and 2D are as follows.

Hypothesis 2C: The negative relation between firm performance and the level of shares collateralized by controlling shareholders is weaker for high cash dividend yield firms than for low cash dividend yield firms.

Hypothesis 2D: The negative relation between firm performance and the level of shares collateralized by controlling shareholders is weaker for high cash plus stock dividend firms than for low cash plus stock dividend firms.

Claessens et al. (1999) pointed out that in West European and East Asian countries, when conglomerate firms are controlled by a controlling shareholder or family, the small shareholders’ interest is more likely to be expropriated by large shareholders. However, this is not the case in United States. However, even in the U.S., the conglomerate firms often transfer wealth among one another through unfair transactions, and according to La Porta et al. (1999), the separation of management and ownership benefits the large shareholders.

The governance issue in conglomerates is quite different from the in non-conglomerate entities. A typical conglomerate includes many diversified and legally independent firms, and affiliate firms are partially financially interlocked. Controlling shareholders or families effectively control the affiliated firms and participate in management.

Moreover, it is easier for the controlling shareholders to transfer funds within conglomerate firms and thus accounting information may have less value for conglomerate firms. Hence, compared to non-conglomerate firms, conglomerate firms will experience more serious agency problems and need more monitoring by the capital markets. This paper argues that the monitoring mechanisms are more important for conglomerate firms and we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Because the transfer of funds within conglomerate firms is less transparent, the monitoring mechanisms are more important for conglomerate firms than for non-conglomerate firms.

IV. Data source and Empirical Models

4.1 SampleThis paper examines the relationship between firm performance and collateralized shares and investigates how monitoring mechanisms reduce the agency problems of collateralized shares. Our sample consists of listed firms in Taiwan, and

the data on collateralized shares held by boards of directors and financial data are from the TEJ database. Since TEJ began to report the proportion of collateralized shares owned by stockholders in 1998, our sample period covers the 3-year period from 1998-2000.

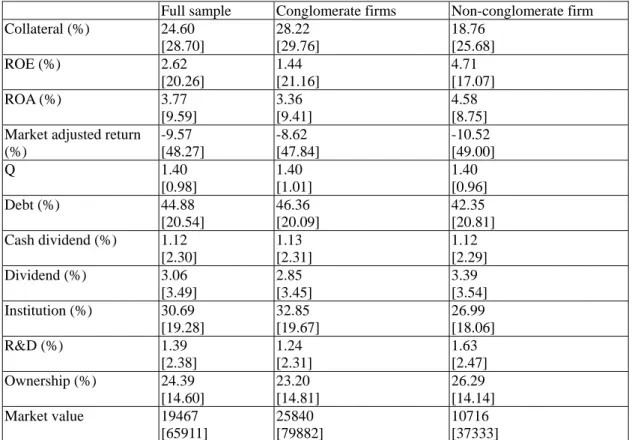

Table 1 shows the mean values and standard deviations in the full sample and two sub-samples, one for conglomerate firms; the other for non-conglomerate firms. For the full sample, the mean of ownership of board of directors and the mean of collateralized share ratio are 24.39% and 24.6%, respectively. The average ownership of board of directors of conglomerate firms is 23.2%, which is lower than that of non-conglomerate firms(26.29%). On the contrary, the average collateralized share ratio for conglomerate firms is 28.2%, which is much higher than the average of collateralized share ratio (18.78%) of non-conglomerate firms. Clearly, the agency problems between the board of directors and outside shareholders is more serious in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms.

[Table 1 about here]

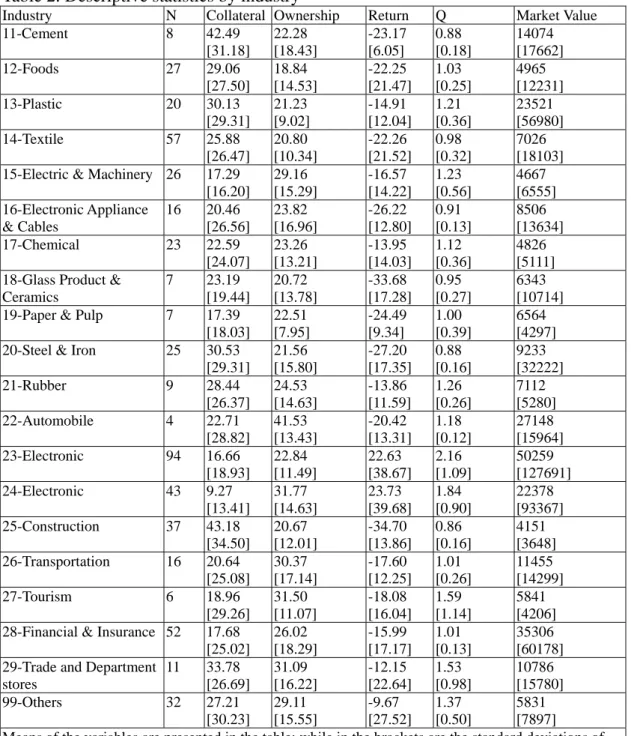

Table 2 summarizes the mean values of collateral ratio and other research variables according to industry. On average, construction and cement industries have the highest collateral ratios, with both having average ratios over 40%. There are followed by the plastics, steel and iron, trade and department store industries have collateral ratios over 30%. The electronics industry has lowest collateral ratio.

[Table 2 about here] 4.2 Variables and model specification

We use accounting profit ratios (ROE and ROA) and Tobin’s Q to measure firm performance. These two measures differ in their time perspectives, since the accounting profit rate is backward-looking, whereas Q is forward-looking. The accounting profit ratio is an estimate of what management has accomplished, whereas Q is an estimate of what management will accomplish. Furthermore, the accounting profit ratio is not affected by investor psychology; but in contrast, Tobin’s Q is strong influenced by investor psychology, because it pertains to forecasts of a multitude of world events that include the outcome of present business strategies (Demsetz and Villalonga, 2000). Because accounting returns and Tobin’s Q reflect different perspectives for firm performance, this paper uses both measures to evaluate firm performance.

To reexamine the relationship between firm performance and shares collateralized by directors, we observe the linkage between the current period’s accounting profit ratios (ROEt and ROAt ) and previous collateral ratio (Collateralt-1).

The first empirical model employed to test the relation between firm performance and shares collateralized by directors (Hypothesis 1) is as follows:

i t t t t t t t t INDUSTRYy OWNERSHIP LogMV D R DEBT COLLATERAL PERF PERF ) ( * ) ( * ) ( * ) & ( * ) ( * ) ( * ) ( * 7 1 6 1 5 1 4 1 3 1 2 1 1 0 (1) where,

PERF =ROE or ROA. These two variables proxy for firm performance.

COLLATERAL = percentage of shares of common stock that is held by directors of the firm and is collateralized to financial institutions.

DEBT = debt-to-asset ratio.

R&D = ratio of research and development expense to net sales.

LogMV = logarithm of the market value of the company’s outstanding common shares.

INDUSTRY = industry dummy. The value is 1 when industry code is equal to 23 or 24; otherwise the value is equal to 0.

Since ROA and ROE measure how efficiently a manager uses resource to produce the output, the independent variables in equation (1) are measured at end of time t-1 (beginning of time t) to match the output at end of time t. In addition to the collateral ratio, we include R&D expense, size, ownership concentration and an industry dummy variable in equation (1) to control for the possible effect of those variables on accounting performance (Demsetz and Lehn, 1985). The relationship between those variables and Tobin’s Q have been validated. Here, we include those variables to check whether this relationship also exists for accounting performance. Debt ratio is included since Chen and Hu (2001) indicated to that controlling shareholders may collateralize shares for funds to finance their firm’s project once the firm’s borrowing is restricted. We also include pervious ROA and ROE to control for missing variables. This procedure is similar to Chen and Hu (2001)

Moreover, to examine whether the agency cost of collateralized shares is more severe in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms, we further divide our full sample into two subgroups: conglomerate firms and non-conglomerate firms and re-test the equation (1).

The sign of regression coefficient 2 is expected to be negative for the entire

sample. Moreover, the negative relation is expected to be more severe in the conglomerate sample than in the non-conglomerate sample.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 test the governance roles of institutional investors, bondholders and dividend policy to reduce the agent conflicts induced from collateralized shares. We employ Tobin’s Q instead of accounting profit ratios as measures for firm performance to examine the investors’ response to the agency costs resulting from collateralized shares and to investigate how the monitoring mechanisms reduce the agency problems. The following empirical models are employed to test the hypotheses 2A, 2B 2C and 2D:

i i OWNERSHIP INDUSTRY LogMV D R MONITOR MONITOR COLLATERAL COLLATERAL Q ) ( * ) ( * ) ( * ) & ( * ) ( * ) * ( * ) ( * 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 (2) where,

The dependent variable:

Q =

asset total of value Book equity of value Market equity of value Book -asset total of value Book , aproxy variable for firm performance. The original version of Tobin’s Q is Market value of equity and debt divided by replacement cost of total asset. However, because market value of debt and replacement cost of total asset are both unavailable, we use an estimate to approximate the original version. We use market value of common stock plus book value of preferred stock and debt (which is equivalent to book value of total asset minus book value of equity plus market value of equity) in the numerator and use book value of total asset in the denominator. This estimate is often called “Pseudo-Q”.

The explanatory variable:

COLLATERAL = percentage of shares of common stock that is held by directors of the firm is collateralized to financial institutions.

The monitoring mechanisms:

MONITOR = This variable represents 4 monitoring mechanisms—INSTITUTION, DEBT, CASH_DIV and DIVIDEND.

DEBT = debt-to-asset ratio.

CASH_DIV = cash dividend yield measured by cash dividends divided by stock price.

DIVIDEND = total dividend yield measured by the sum of cash dividends and stock dividends divided by stock price.

The control variables:

R&D = research and development expenses divided by net sales;

LogMV = logarithm of the market value of the company’s common shares outstanding.

INDUSTRY = industry dummy. The value is 1 when industry code is equal to 23 or 24; otherwise the value is equal to 0

OWNERSHIP = The proportion of shares owned by board of directors.

The variable MONITOR examines the roles of institutional investors, creditors and dividend policy as monitoring agents to reduce the agency conflict induced from collateralized shares, respectively. The sign of coefficient 2 is expected to be positive, implying that these three monitoring mechanisms can efficiently reduce the agency problems induced by collateralized shares.

In addition to collateralized shares and monitoring mechanisms, we include several control variables in the regression equations. Variable OWNERSHIP is included in equations (1) and (2) to control for effect of ownership structure on performance. The relation between ownership structure and performance has been the subject of a ongoing debate in the corporate finance literature (e.g., Morck et al., 1988; McConnell and Servaes, 1990; Loderer and Martin, 1997; Cho, 1998 and Himmelberg et al., 1999). However, the results of these previous studies are mixed. R&D used in Equation (2) is to measure the extent of firms’ investments in intangible assets. Since the denominator omits the value of intangible assets, Pseudo Q is distorted as a measure for firm performance. Thevariable LogMV is a measure of firm size and is included in Equations (1) and (2) to control for possible size effect (for example, Morck et al., 1988; McConnell and Servaes, 1990; Smith and Watts, 1992). The variable INDUSTRY is a dummy variable, 1 for electronic industry (industry code is 23 or 24) and 0 otherwise. The variable INDUSTRY is included in Equations (1) and (2) to control for the relatively high performance of electronic industry in Taiwan stock market.

Hypothesis 3 argues that our monitoring mechanisms are more efficient in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms. To test hypothesis 3, the full sample is divided into two groups again: one for conglomerate firms and non-conglomerate firms and we rerun equation (2) for those two sub-samples.

V. Empirical Results

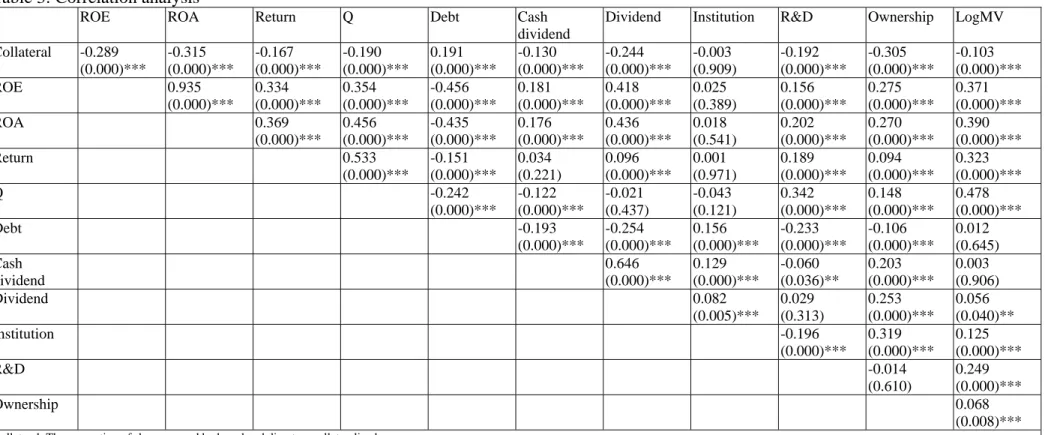

5.1 CorrelationsTable 3 shows the correlation matrix for the sample. The correlations that should be noted are the significantly negative correlations between collateralized shares and 4 alternative measures of firm performance: ROE, ROA, stock return and Q (The correlation coefficients are -0.289, -0.315, -0.167 and -0.190, respectively. ). Consequently, the initial results indicate that the agency problems from collateralized shares reduce the firm performance and also reduce the investors’ evaluation on the firms.

Table 3 also shows that ownership concentration of the board of directors is positively correlated with ROE, ROA, stock return and Q. The correlation coefficients are 0.275, 0.270, 0.094 and 0.148, respectively. The p-values are statistically significant, consistent with the agency theory. Besides, collateralized shares have positive correlation with debt ratio, implying that a firm may use directors’ personal loans to extend the firm is borrowings.

[Table 3 about here] 5.2 Regression results

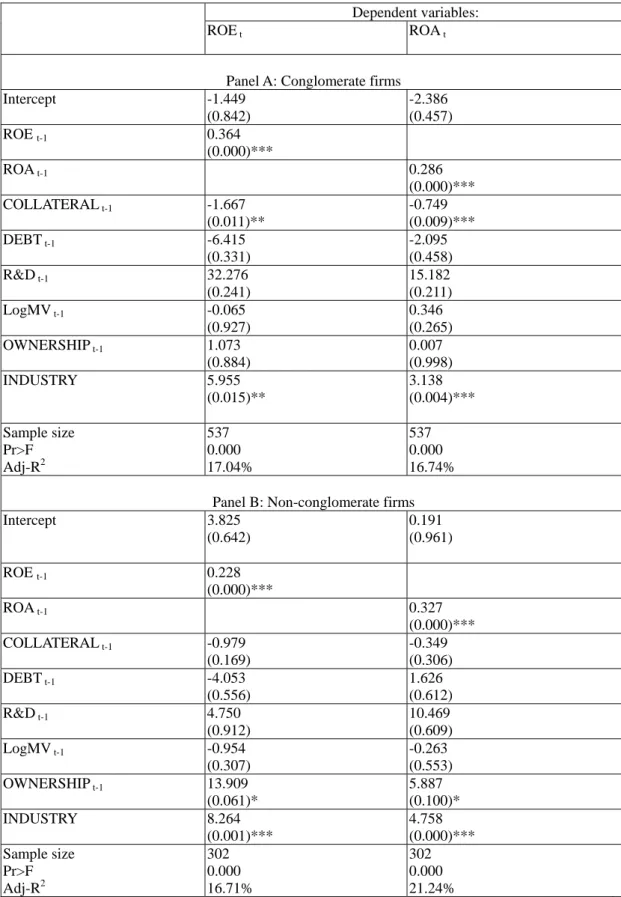

We now discuss the major findings of this study. Table 4 reports the OLS regression estimates of 2 alternative measures of firm performance (ROA and ROE) on collateralized shares for equation (1). The results show that previous-period collateralized shares are significantly negatively related to current-period accounting performance (ROE and ROA) during the sample period. As to other control variables, previous-period ROE (ROA) is positively correlated with current-period ROE (ROA), and the electronics industry (Variable INDUSTRY=1) has higher ROE (ROA) than other industries.

[Table 4 about here]

Table 5 examines whether the effect of agency problems induced by collateralized shares is different for conglomerate firms and for non-conglomerate firms. The OLS results in panels A and B are for conglomerate firms sample and non-conglomerate firms sample, respectively, and the results show that the effect of collateralized shares on firm performance for both sample is quite different. For conglomerate firms, the linkage between accounting profit ratios and collateralized shares is still significantly negative (P-values are 0.011 and 0.009, respectively). This result is consistent with that for the full sample (see Table 4). However, for non-conglomerate firms, the collateralized share ratio plays no role in determining accounting profit ratios (P-values are 0.169 and 0.306, respectively). Table 5 implies that agency problems associated with the collateralized shares are more severe in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms. In sum, the empirical results shown in tables 4 and 5 support our hypothesis 1: There is an inverse relation between firm performance and the level of shares collateralized by controlling shareholders. This inverse relation is more severe in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms.

Tables 4 and 5 show the relations between 2 variables related to controlling shareholders—ownership concentration (OWNERSHIP) and collateralized shares (COLLATERAL)—and accounting performance (ROE and ROA). Table 4 shows that for the overall sample, there is no statistically significant association between ownership concentration and accounting performance, while collateralized shares have a significantly negative impact on firm performance. Once we divide the whole sample into 2 sub-samples, we can see that the agency problems for conglomerate firms and non-conglomerate firms come from difference sources. Panel A of Table 5 indicates the effects of OWNERSHIP and COLLATERAL on ROE and ROA for conglomerate firms. The effect of OWNERSHIP is not statistically significant and the effect of COLLATERAL is significantly negative. This result shows that for conglomerate firms, the ownership concentration of board of directors is useless for reduction of agency problem between controlling shareholder and outside investors, which does not support the traditional agency theory. However, the deviation between control right and cash flow right exacerbated by collateralized shares induces the agency problem and significantly decreases firm performance. In other words, for individuals or entities investing in conglomerate firms, collateralized

shares by boards of directors have more severe agency problems than low ownership concentration.

On the other hand, the result for non-conglomerate firms is the opposite (Panel B of Table 5). The effect of OWNERSHIP on ROE and ROA is significantly positive, while the negative impact of COLLATERAL is not significant. This implies that for non-conglomerate firms, a high ownership concentration of controlling shareholders can reduce potential agency problems and further improve firm performance. However, the agency problem induced by collateralized shares is not severe enough to impact firm performance.

[Table 5 about here]

Regression equation (2) is used to examine the impact of collateralized shares on Q and test whether the three monitoring mechanisms alleviate the impact. The dependent variable in equation (2) is the Q ratio, where Q is defined as the amount of book value of total asset minus book value plus market value of equity divided by total assets. Q is used as a proxy for Tobin’s Q, which is a popular measurement of firm performance (For example, Morck et al., 1998; Yermack, 1996; Lang and Stulz, 1994).

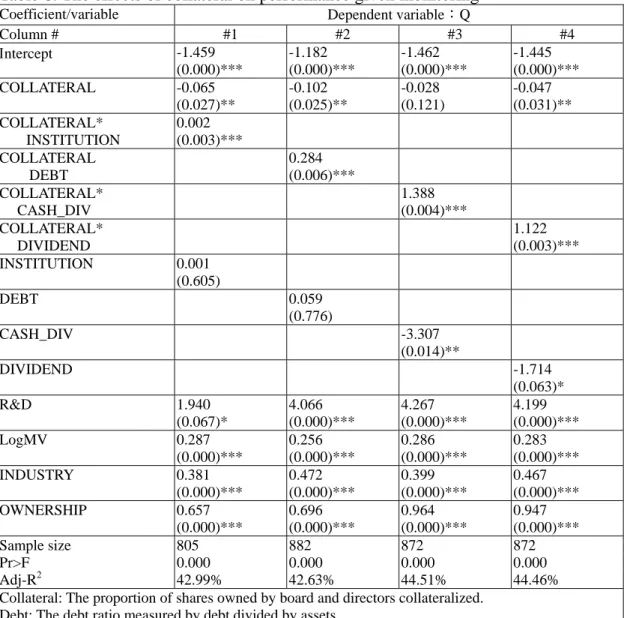

Results for regression equations (2), displayed in Table 6, support the hypotheses 2A, 2B, 2C and 2D. The coefficient for variable COLLATERAL is significantly negative, indicating that collateralized shares decrease firm value. The coefficients for the interaction terms COLLATERAL*INSTITUTION (in column #1), COLLATERAL*DEBT (in column #2), COLLATERAL*CASH_DIV (in column #3) and COLLATERAL*DIVIDEND (in column #4) are 0.002, 0.284, 1.388 and 1.122, respectively (P-values are 0.003, 0.006, 0.004 and 0.003, respectively). Those coefficients are all significantly positive. Thus, adequate monitoring mechanisms can effectively reduce the negative impact of collateralized shares on firm performance.

Results when the monitoring effect of institutional investors is considered (column #1), indicate a positive, statistically significant estimate 2 on the interaction COLLATERAL*INSTITUTION; which implies that the impact of

collateralized shares on Q varies directly with the holdings of institutional investors. The magnitude of 12(INSTITUTION) measures the impact of collateralized shares on Q conditional on different levels of institutional holdings. Column 1 of Table 6 shows that ˆ1 is equal to -0.065 and ˆ2 is equal to The estimates

1

and 2, evaluated for an average firm with percentage of institutional holding of 30.69 (from Table 1), indicate that the average effect of collateralized shares on Q is

0036 . 0 ) 69 . 30 ( 002 . 0 065 . 0 ) ( 2 1 meanof INSTITUTION . That is,

for a firm without institutional holdings, Q is decreased by an amount of 0.065 for each unit of collateral share increase. However, for firms with a percentage of institutional holding of 30.69%, Q is decreased only 0.0036. Thus, we conclude that institutional holding is an effective way to alleviate the negative impact of collateralized shares on Q.

The reasoning is similar for the results considering monitoring effects of creditors (column #2), cash dividend (column #3) and cash plus stock dividend (column #4). The coefficients of COLLATERAL are all significantly negative and the coefficients of COLLATERAL*DEBT (in column #2), COLLATERAL*CASH_DIV (in column #3) and COLLATERAL*DIVIDEND (in column #4) are all significantly positive. These results indicate that the agency problems between outside investors and controlling shareholders hurt the firm performance. However, the specified monitoring mechanisms could mitigate the effect of agency costs on firm performance.

As to other control variables, Table 6 shows that R&D expenditure has positive effects on Q. We attribute this to the distortions that occur in the denominator of Q because accounting practices do not treat intangible and tangible capital similarly. The relation between ownership concentration and Q is also significantly positive, which is consistent with agency theory as proposed by Jensen and Meckling (1976). Furthermore, the firm size has positive linkage with Q and the electronics industry has higher Q value than other industries.

[Table 6 about here]

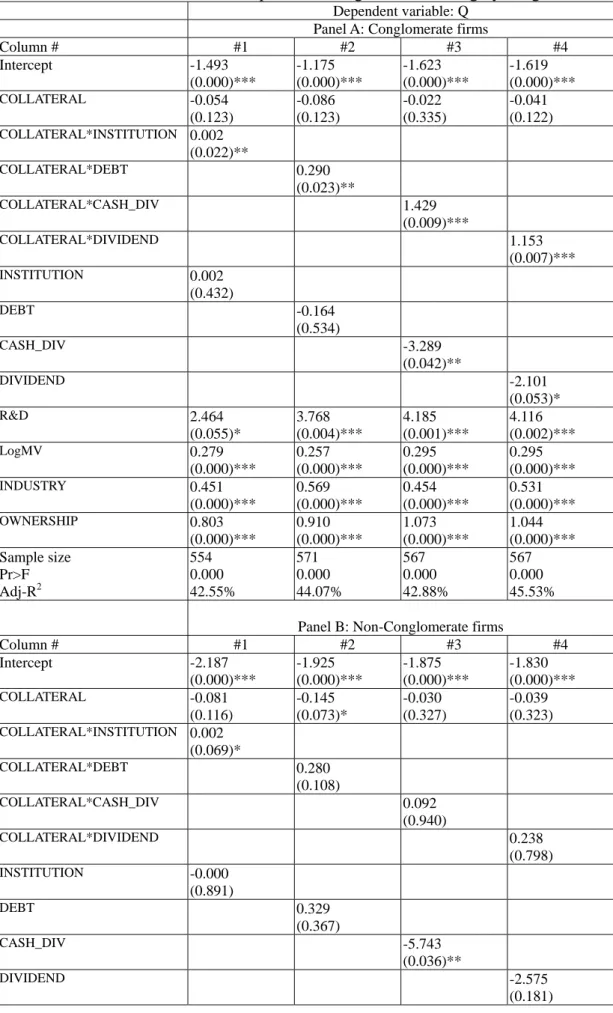

Table 5 supports the argument that agency problems from collateralized shares are more severe in conglomerate firms. Thus, the expected profit in reducing agency problems from monitoring mechanisms should be higher in conglomerate firms than in non-conglomerate firms (hypothesis 3). The results displayed in Table 7 support

this argument, and results for the conglomerate sub-sample are similar to those for full sample (see panel A of Table 7). Thus, the proposed monitoring mechanisms effectively lessen the negative impact of collateralized shares on Q. On the other hand, results for the non-conglomerate sub-sample are inconsistent with those for the full sample (see panel B of table 7). The agency conflict is not severe for non-conglomerate firms and investors do not require costly control mechanisms to monitor the controlling shareholders.

In sum, the coefficients for the interaction terms of collateralized shares and monitoring mechanisms measure how the relation between collateralized shares and firm performance is influenced by monitoring mechanisms. The empirical results support our hypotheses.

[Table 7 about here]

VI. Conclusion

This study investigates the effects of three mechanisms to reduce agency conflicts for mitigating the agency problems induced by directors collateralizing their shares. This study hypothesizes that the use of debt, institutional holding and dividend distribution all could mitigate agency problem related to the collateralization. The empirical evidence provided in this study support these proposed hypotheses.

REFERENCE

Agrawal, A. and G. N. Mandelker, 1990, Large shareholders and the monitoring of managers: The case of anti-takeover charter amendments, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 25: 143-161.

Ambarish, R., K. John, and J. Williams, 1987, Efficient signalling with dividends and investments, Journal of Finance 42: 321-343.

Bathala, C. T., K. P. Moon and R. P. Rao, 1994, Managerial ownership, debt policy, and the impact of institutional holdings: An agency theory perspective, Financial Management 23: 38-50.

Bushman, R. and A. Smith, 2001, Financial accounting information and corporate governance, Journal of Accounting and Economics 32: 237-333.

Bushman, R. and R. Indjejiikian, 1993, Accounting income, stock price and managerial compensation, Journal of Accounting and Economics 16: 1-23. Bushman, R., Q. Chen, E. Engel, and A. Smith, 2000, The sensitivity of corporate

governance systems to the timeliness of accounting earnings, working paper, University of Chicago.

Chen, Y. and S. Hu, 2001, The controlling shareholder’s personal stock loan and firm performance, working paper, National Taiwan University.

Chiou, Jeng-Ren, Ta-Chung Hsiung, and Lanfeng Kao (2002), A Study of the Relationship between Financial Distress and Collateralized Shares, Taiwan Accounting Review 3(1): 79-111.

Cho, M. H., 1998, Ownership structure, investment and the corporate value: An empirical analysis, Journal of Financial Economics 47: 103-121.

Claessens, S., S. Djankov and L. Lang, 1999, Expropriation of minority shareholders in East Asia, Working paper, World Bank, Washington, DC.

DeAngelo, H., L. DeAngelo and D. Skinner, 1996, Reversal of fortune: Dividend signaling and the disappearance of sustained earnings growth, Journal of Financial Economics 40: 341-371.

Demsetz, H. and B. Villalonga, 2000, Ownership structure and corporate performance, working paper, University of California, Los Angeles.

Fama, E. F., 1980, Agency problem and the theory of the firm, Journal of Political Economy 88: 288-307.

Feltham, G. A and J. Xie, 1994, Performance measure congruity and diversity in multi-task principal/agent relations, Accounting Review 69: 429-453.

Fluck, Z., 1999, The dynamics of management-shareholder conflict, Review of Financial Studies 12: 347-377.

Gomes, A., 2000, Going public with asymmetric information, agency costs and dynamic trading, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Grossman, S. and O. Hart, 1982, Corporate financial structure and managerial incentives, in J. J. McCall Ed: The Economics of Information and Uncertainty, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 123-155.

Himmelberg, C. P, R. G. Hubbard and D. Palia, 1999, Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance, Journal of Financial Economics 53: 353-384.

Ittner, C., D. Larcker and M. Rajan, 1997, The choice of performance measures in annual bonus contracts, Accounting Review 72: 231-255.

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling, 1976, Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure, Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305-360. Jensen, M., 1986, Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeover,

American Economic Review 76: 323-329.

Kao, Lanfeng and Jeng-Ren Chiou, 2002, The Effect of Collateralized shares on Informativeness of Accounting Earnings, working paper.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer and R. Vishny, 1998, Law and finance, Journal of Political Economy 106: 1113-1155.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer and R. Vishny, 2000a, Investor protection and corporate governance, Journal of Financial Economics 58: 3-27. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer and R. Vishny, 2000b, Agency problems

and dividend policies around the world, Journal of Finance 55:1-33.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer, 1999, Corporate ownership around the world, Journal of Finance 54: 471-517.

Lee, T., 2001, The Effect of Corporate Governance on the Related-Party Transaction, Master thesis, Graduate Institute of Finance, Fu-Jen University.

Levine, R., 1997, Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda, Journal of Economic Literature 35: 688-726.

Loderer, C. and K. Martin, 1997, Executive stock ownership and performance: Tracking faint traces, Journal of Financial Economics 45: 223-255.

McConnell, J. and H. Servaes, 1990, Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value, Journal of Financial Economics 27: 595-612.

Miller, M. H. and F. Modigliani, 1961, Dividend policy, growth and the valuation of shares, Journal of Business 34: 411-433.

Miller, M. H. and K. Rock, 1985, Dividend policy under asymmetric information, Journal of Finance 40: 1031-1051.

Morck, R., A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny, 1988, Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis, Journal of Financial Economics 20, 293-315. Seetharaman, A., L. S. Zane and S. Bin, 2001, Analytical and empirical evidence of

the impact of tax rates on the trade-off between debt and managerial ownership, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 16: 249-272.

Shen, Y. P. and C. J. Huang, 2001, Subsidiary trading in parent stocks: Trading behavior of major Taiwan corporations, Journal of Financial Studies 9: 53-70. Shleifer, A. and R. Vishny, 1986, Large shareholders and corporate control, Journal of

Political Economy 94: 461-488.

Shleifer, A. and R. Vishny, 1997, A survey of corporate governance, Journal of Finance 52: 117-142.

Williamson, O., 1988, Corporate finance and corporate governance, Journal of Finance 48: 567-592.

Yeh, Y. H. and T. S. Lee, 2001, Corporate governance and performance: The case of Taiwan, The Seventh Asia Pacific Finance Association Annual Conference, Shanghai.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics by conglomerate

Full sample Conglomerate firms Non-conglomerate firm Collateral (%) 24.60 [28.70] 28.22 [29.76] 18.76 [25.68] ROE (%) 2.62 [20.26] 1.44 [21.16] 4.71 [17.07] ROA (%) 3.77 [9.59] 3.36 [9.41] 4.58 [8.75] Market adjusted return

(%) -9.57 [48.27] -8.62 [47.84] -10.52 [49.00] Q 1.40 [0.98] 1.40 [1.01] 1.40 [0.96] Debt (%) 44.88 [20.54] 46.36 [20.09] 42.35 [20.81] Cash dividend (%) 1.12 [2.30] 1.13 [2.31] 1.12 [2.29] Dividend (%) 3.06 [3.49] 2.85 [3.45] 3.39 [3.54] Institution (%) 30.69 [19.28] 32.85 [19.67] 26.99 [18.06] R&D (%) 1.39 [2.38] 1.24 [2.31] 1.63 [2.47] Ownership (%) 24.39 [14.60] 23.20 [14.81] 26.29 [14.14] Market value 19467 [65911] 25840 [79882] 10716 [37333]

Means of the variables are presented in the table; while in the brackets are the standard deviations of the variables.

Collateral: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors collateralized. ROE: Return on equity.

ROA: Return on assets.

Market adjusted return: Annual return minus annual market return. Debt: The debt ratio measured by debt divided by assets.

Cash Dividend: The cash dividend yield measured by cash dividend divided by stock price.

Dividend: The total dividend yield measured by the sum of cash dividend and stock dividend divided by stock price.

Institution: The proportion of shares of the firm owned by institutional investors. R&D: R&D expenses divided by net sales.

Ownership: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors. LogMV; The logarithm of market value.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics by industry

Industry N Collateral Ownership Return Q Market Value 11-Cement 8 42.49 [31.18] 22.28 [18.43] -23.17 [6.05] 0.88 [0.18] 14074 [17662] 12-Foods 27 29.06 [27.50] 18.84 [14.53] -22.25 [21.47] 1.03 [0.25] 4965 [12231] 13-Plastic 20 30.13 [29.31] 21.23 [9.02] -14.91 [12.04] 1.21 [0.36] 23521 [56980] 14-Textile 57 25.88 [26.47] 20.80 [10.34] -22.26 [21.52] 0.98 [0.32] 7026 [18103] 15-Electric & Machinery 26 17.29

[16.20] 29.16 [15.29] -16.57 [14.22] 1.23 [0.56] 4667 [6555] 16-Electronic Appliance & Cables 16 20.46 [26.56] 23.82 [16.96] -26.22 [12.80] 0.91 [0.13] 8506 [13634] 17-Chemical 23 22.59 [24.07] 23.26 [13.21] -13.95 [14.03] 1.12 [0.36] 4826 [5111] 18-Glass Product &

Ceramics 7 23.19 [19.44] 20.72 [13.78] -33.68 [17.28] 0.95 [0.27] 6343 [10714] 19-Paper & Pulp 7 17.39

[18.03] 22.51 [7.95] -24.49 [9.34] 1.00 [0.39] 6564 [4297] 20-Steel & Iron 25 30.53

[29.31] 21.56 [15.80] -27.20 [17.35] 0.88 [0.16] 9233 [32222] 21-Rubber 9 28.44 [26.37] 24.53 [14.63] -13.86 [11.59] 1.26 [0.26] 7112 [5280] 22-Automobile 4 22.71 [28.82] 41.53 [13.43] -20.42 [13.31] 1.18 [0.12] 27148 [15964] 23-Electronic 94 16.66 [18.93] 22.84 [11.49] 22.63 [38.67] 2.16 [1.09] 50259 [127691] 24-Electronic 43 9.27 [13.41] 31.77 [14.63] 23.73 [39.68] 1.84 [0.90] 22378 [93367] 25-Construction 37 43.18 [34.50] 20.67 [12.01] -34.70 [13.86] 0.86 [0.16] 4151 [3648] 26-Transportation 16 20.64 [25.08] 30.37 [17.14] -17.60 [12.25] 1.01 [0.26] 11455 [14299] 27-Tourism 6 18.96 [29.26] 31.50 [11.07] -18.08 [16.04] 1.59 [1.14] 5841 [4206] 28-Financial & Insurance 52 17.68

[25.02] 26.02 [18.29] -15.99 [17.17] 1.01 [0.13] 35306 [60178] 29-Trade and Department

stores 11 33.78 [26.69] 31.09 [16.22] -12.15 [22.64] 1.53 [0.98] 10786 [15780] 99-Others 32 27.21 [30.23] 29.11 [15.55] -9.67 [27.52] 1.37 [0.50] 5831 [7897] Means of the variables are presented in the table; while in the brackets are the standard deviations of the variables.

Table 3: Correlation analysis

ROE ROA Return Q Debt Cash

dividend

Dividend Institution R&D Ownership LogMV

Collateral -0.289 (0.000)*** -0.315 (0.000)*** -0.167 (0.000)*** -0.190 (0.000)*** 0.191 (0.000)*** -0.130 (0.000)*** -0.244 (0.000)*** -0.003 (0.909) -0.192 (0.000)*** -0.305 (0.000)*** -0.103 (0.000)*** ROE 0.935 (0.000)*** 0.334 (0.000)*** 0.354 (0.000)*** -0.456 (0.000)*** 0.181 (0.000)*** 0.418 (0.000)*** 0.025 (0.389) 0.156 (0.000)*** 0.275 (0.000)*** 0.371 (0.000)*** ROA 0.369 (0.000)*** 0.456 (0.000)*** -0.435 (0.000)*** 0.176 (0.000)*** 0.436 (0.000)*** 0.018 (0.541) 0.202 (0.000)*** 0.270 (0.000)*** 0.390 (0.000)*** Return 0.533 (0.000)*** -0.151 (0.000)*** 0.034 (0.221) 0.096 (0.000)*** 0.001 (0.971) 0.189 (0.000)*** 0.094 (0.000)*** 0.323 (0.000)*** Q -0.242 (0.000)*** -0.122 (0.000)*** -0.021 (0.437) -0.043 (0.121) 0.342 (0.000)*** 0.148 (0.000)*** 0.478 (0.000)*** Debt -0.193 (0.000)*** -0.254 (0.000)*** 0.156 (0.000)*** -0.233 (0.000)*** -0.106 (0.000)*** 0.012 (0.645) Cash dividend 0.646 (0.000)*** 0.129 (0.000)*** -0.060 (0.036)** 0.203 (0.000)*** 0.003 (0.906) Dividend 0.082 (0.005)*** 0.029 (0.313) 0.253 (0.000)*** 0.056 (0.040)** Institution -0.196 (0.000)*** 0.319 (0.000)*** 0.125 (0.000)*** R&D -0.014 (0.610) 0.249 (0.000)*** Ownership 0.068 (0.008)***

Collateral: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors collateralized. ROE: Return on equity.

ROA: Return on assets.

Market adjusted return: Annual return minus annual market return. Debt: The debt ratio measured by debt divided by assets.

Cash Dividend: The cash dividend yield measured by cash dividend divided by stock price.

Dividend: The total dividend yield measured by the sum of cash dividend and stock dividend divided by stock price. Institution: The proportion of shares of the firm owned by institutional investors.

R&D: R&D expenses divided by net sales.

Ownership: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors. LogMV; The logarithm of market value.

Dependent variables: ROE t ROA t Intercept -0.430 (0.935) -1.983 (0.403) ROE t-1 0.285 (0.000)*** ROA t-1 0.258 (0.000)*** COLLATERAL t-1 -1.437 (0.004)*** -0.618 (0.006)*** DEBT t-1 -6.874 (0.152) -1.562 (0.457) R&D t-1 22.232 (0.328) 12.891 (0.208) LogMV t-1 -0.210 (0.689) 0.242 (0.304) OWNERSHIP t-1 6.701 (0.210) 2.822 (0.239) INDUSTRY 6.633 (0.000)*** 3.707 (0.000) Sample size 841 841 Pr>F 0.000 0.000 Adj-R2 16.79% 18.04%

ROE: Return on equity. ROA: Return on assets.

Collateral: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors collateralized. Debt: The debt ratio measured by debt divided by assets.

R&D: R&D expenses divided by net sales. LogMV; The logarithm of market value.

Ownership: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors. Industry: 1 for electronic firms and 0 otherwise.

Table 5: Regression analyses of collateral on performance by conglomerate

Dependent variables:

ROE t ROA t

Panel A: Conglomerate firms Intercept -1.449 (0.842) -2.386 (0.457) ROE t-1 0.364 (0.000)*** ROA t-1 0.286 (0.000)*** COLLATERAL t-1 -1.667 (0.011)** -0.749 (0.009)*** DEBT t-1 -6.415 (0.331) -2.095 (0.458) R&D t-1 32.276 (0.241) 15.182 (0.211) LogMV t-1 -0.065 (0.927) 0.346 (0.265) OWNERSHIP t-1 1.073 (0.884) 0.007 (0.998) INDUSTRY 5.955 (0.015)** 3.138 (0.004)*** Sample size 537 537 Pr>F 0.000 0.000 Adj-R2 17.04% 16.74%

Panel B: Non-conglomerate firms Intercept 3.825 (0.642) 0.191 (0.961) ROE t-1 0.228 (0.000)*** ROA t-1 0.327 (0.000)*** COLLATERAL t-1 -0.979 (0.169) -0.349 (0.306) DEBT t-1 -4.053 (0.556) 1.626 (0.612) R&D t-1 4.750 (0.912) 10.469 (0.609) LogMV t-1 -0.954 (0.307) -0.263 (0.553) OWNERSHIP t-1 13.909 (0.061)* 5.887 (0.100)* INDUSTRY 8.264 (0.001)*** 4.758 (0.000)*** Sample size 302 302 Pr>F 0.000 0.000 Adj-R2 16.71% 21.24%

ROE: Return on equity. ROA: Return on assets.

Market adjusted return: Annual return minus annual market return.

Collateral: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors collateralized. Debt: The debt ratio measured by debt divided by assets.

R&D: R&D expenses divided by net sales. LogMV; The logarithm of market value.

Ownership: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors. Industry: 1 for electronic firms and 0 otherwise.

Table 6: The effects of collateral on performance given monitoring

Coefficient/variable Dependent variable:Q

Column # #1 #2 #3 #4 ntercept -1.459 (0.000)*** -1.182 (0.000)*** -1.462 (0.000)*** -1.445 (0.000)*** COLLATERAL -0.065 (0.027)** -0.102 (0.025)** -0.028 (0.121) -0.047 (0.031)** COLLATERAL* INSTITUTION 0.002 (0.003)*** COLLATERAL DEBT 0.284 (0.006)*** COLLATERAL* CASH_DIV 1.388 (0.004)*** COLLATERAL* DIVIDEND 1.122 (0.003)*** INSTITUTION 0.001 (0.605) DEBT 0.059 (0.776) CASH_DIV -3.307 (0.014)** DIVIDEND -1.714 (0.063)* R&D 1.940 (0.067)* 4.066 (0.000)*** 4.267 (0.000)*** 4.199 (0.000)*** LogMV 0.287 (0.000)*** 0.256 (0.000)*** 0.286 (0.000)*** 0.283 (0.000)*** INDUSTRY 0.381 (0.000)*** 0.472 (0.000)*** 0.399 (0.000)*** 0.467 (0.000)*** OWNERSHIP 0.657 (0.000)*** 0.696 (0.000)*** 0.964 (0.000)*** 0.947 (0.000)*** Sample size 805 882 872 872 Pr>F 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Adj-R2 42.99% 42.63% 44.51% 44.46%

Collateral: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors collateralized. Debt: The debt ratio measured by debt divided by assets.

Cash Dividend: The cash dividend yield measured by cash dividend divided by stock price.

Dividend: The total dividend yield measured by the sum of cash dividend and stock dividend divided by stock price.

Institution: The proportion of shares of the firm owned by institutional investors. R&D: R&D expenses divided by net sales.

LogMV; The logarithm of market value. Industry: 1 for electronic firms and 0 otherwise.

Ownership: The proportion of shares owned by board and directors. ***, ** and * represent 1%, 5% and 10% significant levels, respectively.