This article was downloaded by:[Chang, Wei-Wen] [Chang, Wei-Wen] On: 12 June 2007

Access Details: [subscription number 779424203] Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Human Resource Development

International

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713701210

The negative can be positive for cultural competence

To cite this Article: Chang, Wei-Wen , 'The negative can be positive for cultural competence', Human Resource Development International, 10:2, 225 - 231 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/13678860701347206URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13678860701347206

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use:http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

Perspectives on Theory

The Negative can be Positive

for Cultural Competence

WEI-WEN CHANG

National Taiwan Normal UniversityABSTRACT The trend of globalization has provoked a wide discussion with regard to cultural competence. In studies regarding cultural competence, researchers have often focused on the positive aspect in order to acquire insights and implications for other practitioners. However, intercultural dynamics involve multiple individuals with diverse backgrounds, for whom these positive aspects convey only a part of their cultural competence. Whereas, in the literature, individuals’ negative feelings are often treated as problems that need to be solved and cured, the purpose of this article is to elaborate on the need to include individuals’ reactions and emotional feelings in research regarding cultural competence.

KEY WORDS: Cultural competence, international HRD, intercultural research, expatriate workers

Today, technology and global economy have blurred national boundaries and significantly increased the interaction between different cultural groups. This trend provokes a wide discussion with regard to cultural competence in various fields, such as that of expatriate business people (e.g. Forster, 2000; Mendehall and Stahl, 2000; Okeefe, 2003; Suutari and Burch, 2001), health care providers (e.g. Bazaldua, 2004; Betancourt et al., 2003; Campinha-Bacote, 2002; Green-Hernandez et al., 2004; MacNaughton, 2002), school educators (e.g. Dana et al., 2002), social workers (McPhatter, 1997). As cultural competence has turned into an essential requirement for many workers in multicultural settings, it has also become a major issue for HRD professionals. For example, Harris (2006) examined the humanitarian aid on post-tsunami Sri Lanka and contended that due to insensitivity to the local disaster needs, increasing recruitment and HRD with international aid agencies resulted in a human resource crisis for local organizations and decreased their emergency response capacities.

Correspondence Address:Wei-Wen Chang, Graduate Institute of International Workforce Education and Development, National Taiwan Normal University, 162, Sec.1, Ho-Ping E. Road, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C. 106. Email: changw@ntnu.edu.tw

Vol. 10, No. 2, 225 – 231, June 2007

ISSN 1367-8868 Print/1469-8374 Online/07/020225-07 Ó 2007 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13678860701347206

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

In studies regarding cultural competence, researchers have often focused on the positive aspect in order to acquire insights and implications for other practitioners. For example, to understand the process of intercultural competence, Taylor (1994) interviewed 12 participants who had had positive experiences of living abroad. In addition, several authors have identified components of cultural competence, and most of these components are associated with positive descriptions, such as having respectful, appreciative, and sensitive attitudes (Campinha-Bacote, 1998, 2002). However, as Cross (2001) wrote, such a description of cultural competence seems ‘idealistic’ (para. 2). Intercultural dynamics involve multiple individuals with diverse backgrounds, for whom these positive aspects convey only a part of their cultural competence. Whereas, in the literature, individuals’ negative feelings are often treated as problems that need to be solved and cured, the purpose of this article is to elaborate on the need to include individuals’ reactions and emotional feelings in research regarding cultural competence.

Connotations of Cultural Competence in the Literature

Campinha-Bacote (2002) identified five components in the process of cultural competence of healthcare practitioners, these being (p. 183):

1. culture awareness: the respectful, appreciative, and sensitive attitudes toward values, beliefs, lifestyles, practices and problem-solving strategies of people from other cultures.

2. cultural skill: the ability to collect information and conduct accurate cultural assessment.

3. cultural knowledge: an understanding of people’s values, worldviews, culture-bound illnesses and health-related needs.

4. cultural encounters: a direct engagement in face-to-face cross-cultural interac-tion, whereby cultural knowledge can be enhanced and adjusted.

5. cultural desire: people are willing to actively engage in the process of attaining cross-cultural competence. They want to continue this process instead of having to. Similarly, Lister (1999) presented a taxonomy to develop a culturally competent practitioner. The taxonomy includes cultural awareness, knowledge, understanding, sensitivity, and competence.

1. cultural awareness: the ability to describe the cultural influence of people’s values and beliefs.

2. cultural knowledge: becoming familiar with similarities, differences, and inequalities among different cultural groups.

3. cultural understanding: recognizing the influence of the dominant culture on individuals or groups from other cultural backgrounds and the problems these groups have faced.

4. cultural sensitivity: showing regard for the values and practices within a cultural context and being aware of one’s own culture and its influence.

5. cultural competence: providing care that respects people’s cultural beliefs and addresses their disadvantage due to unequal power relations in society. 226 W.-W. Chang

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

Heeding the fact that cultural competence is made up of multiple perspectives, Betancourt et al. (2003) also noted that a number of terms have been used to better articulate the meaning of cultural competence. The different terms include cultural sensitivity, cultural responsiveness, cultural effectiveness, and cultural humility. Similarly, Papadopulos (2003) also suggested a model that consists of four com-ponents: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural sensitivity and cultural competence.

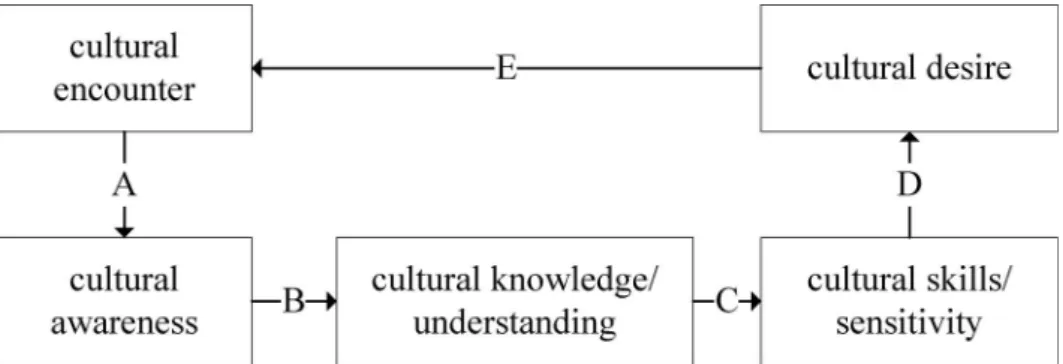

The connotations from the reviewed literature can be integrated, as shown in Figure 1. The process begins from a cultural encounter that often raises people’s cultural awareness (Line A). For example, working with diverse populations or accepting an expatriate assignment invites people to engage in cultural issues. It is common that people do not feel the existence of their own culture until they meet another one and are faced with the differences. Line B indicates that as cultural awareness increases and people learn more about their own and other cultures, cultural knowledge and understanding gain accordingly. Further, Line C shows that, with a higher level of cultural understanding, culturally sensitive behaviours are more likely to occur. At this stage, cultural skills are demonstrated through various observable behaviours and practice. Finally, Lines D and E suggest that if the process of cultural competence continues, the expatriate desires to be more deeply involved in different cultures and to consistently engage in cultural encounters (Figure 1).

A Missing Component

Becoming culturally competent is a learning process (McPhatter, 1997; Taylor, 1994) that involves individuals’ cognitive change. For expatriate workers, their motivation, perception of their career, self-understanding and emotional reactions often affect their adjustment and performance in the host culture (Stahl et al., 2002; Varner and Palmer, 2005). Personal emotional reaction toward cross-cultural incidents can be either a catalyst or a block to the competence process. However, in the above-mentioned process of attaining cultural competence, individual reaction has received limited attention, yet emotional reactions are natural and frequent during cross-cultural encounters. In the current literature, authors pay a significant amount of attention to cultural awareness, understanding, and sensitivity, but relatively little to

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

the individuals’ psychological reactions and their influence on the process of acquiring cultural competence. Although some articles have explored cross-cultural failures of expatriate executives (Rankis and Beebe, 1982; Rao et al., 2005) and teachers in multicultural settings (Eder and McClusky, 1996), these studies did not further investigate how the negative aspects affected their cultural learning.

In the field of multinational management, studies have discussed the emotional stress faced by expatriates during their international assignments. For example, McFarland (1996) interviewed US expatriates in Europe and found that these workers often felt unprepared, misunderstood and forgotten. Expatriates faced high failure rate for various kinds of stress, such as cultural shock, family problems, miscommunication and difficulties in language as well as social life (Rankis and Beebe, 1982; Selmer and Leung, 2002; Suutari et al., 2002). Similarly, expatriates working for non-profit organizations also experienced emotional challenges (Bjerneld et al., 2004) or unexpected results (Harris, 2006; Pfeiffer, 2003) when they served in different countries. From 2005 to 2006, I interviewed 15 expatriate workers who have provided international humanitarian assistance in Asia and Africa. When they stepped into a new cultural context, they were faced with conflicting values and negative feelings. For example, a nurse felt frustrated when she saw patients’ families choose not to request any emergent interventions for dying patients. ‘They [the local people] have their own culture . . . . the family did not want us to conduct any interventions. Many times, we felt helpless . . . . I was sad. Why was a life so cheap?’ Similarly, a pastor shared his surprise when learning that in the Thai village where he served, the local people would take twin babies to be cursed monsters while in his own homeland people would view twins as a treasure. Such conflicting values do exist between cultures, and such conflicted feelings do not melt away simply by advocating acceptance or respect of other cultures. Similarly, a female evangelist expressed her shock and frustration when she realized that the group she served did not view human life as valuable. She said,

[In the village] I once saw a mother crying after her baby was buried. I thought the mother cried for the baby, but she explained that she cried because we had used her family’s only blanket to wrap the baby. The mother cried for the blanket, but not her child . . . . Faced with these local situations, I often felt very frustrated.

These humanitarian workers have served in underdeveloped areas providing educational service and medical assistance for years. Their experiences indicate that although negative emotion might sometimes cause an end to their participation in intercultural work, in some cases, negative energy could become an important catalyst for further learning during cultural conflicts.

For those workers who need to consistently face intercultural challenges, the accompanying culture shock, frustrations, and experience of failure are problems as well as solutions. By overlooking a considerable part of the individuals’ reactions (e.g. sadness, resistance, rejection), we could miss seeing some critical obstacles and opportunities that people must experience in becoming culturally adapted.

In cultural competence literature, researchers often suggest that intercultural workers acquire outside world experience, gain knowledge of another culture, and 228 W.-W. Chang

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

become sensitive to that culture’s needs; however, the literature provides little information concerning how to deal with fundamental differences or even minor conflicts between the target culture and one’s own. For example, Caffarella and Merriam (2000) discuss a scenario about cultural misinterpretation in teaching. In order to encourage a Taiwanese student to participate more in the class discussion in a US graduate class, the instructor read the student’s outstanding paper to the class. However, this recognition seemed to embarrass the student. The quality of her future papers dropped, and her participation did not increase either. Caffarella and Merriam placed the responsibility of recognizing cultural differences on the teachers’ shoulders and wrote ‘the professor is [sic] focused on the individual learner. Though well-intentioned, ignoring the student’s cultural context impacted negatively on the student’s subsequent learning’ (p. 64). In emphasizing the teacher’s responsibility, they overlooked another dimension, the teacher’s cultural background. In this case, although the teacher had, based on his past experience, made the best decision from his point of view, this decision led to an unexpected negative consequence. This scenario indicates that the real challenge for those who work in intercultural settings is not only how to respond to the target groups’ cultural background, but how to deal with the dynamic that exists between both the served groups’ and his/her own cultural background. In other words, while it is pivotal to consider how to become sensitive to other cultures, it is also equally important to pay attention to the possible conflicts, difficulties, resistance and frustration that occur within the workers during the encounter of the two different cultural backgrounds. This presents HRD practitioners with two suggested courses of action. First, faced with complicated problems in cross-cultural contexts, HRD people should develop the competence to move beyond the surface of frustrated situations and view the various conflicts as opportunities for them to discern the real facets of different cultures. Second, while designing programmes for multicultural workers, HRD practitioners can help learners to handle negative experiences in cross-cultural settings through discussing both success and failure stories in class, and encouraging participants to examine changes within themselves that occurred during various cultural incidents. Therefore, an important task for HRD programme designers is to create a safe learning environment in which participants can place positive and negative experiences on the table for self-examination and reflection.

When people step out of their comfort zones to face a different culture, values and lifestyles, having a sense of resistance is part of a natural reaction. The complexity of the process in gaining cultural competence cannot be revealed if studies merely focus on the positive aspects and suggest people consistently attain to other cultures rather than allowing them to honestly confront the differences between the two sides. Anderson (1990) uses ‘good-guy liberalism’ to describe those people who believe that ‘all the world’s problems would melt away if we just had a tad more tolerance’ (p. 4). However, the real challenge is that tolerance does not come easily or automatically. In today’s world, some children are still educated in classes of racial groups determined by their colour and taught to ethnocentrically distinguish themselves from people of different cultures. Even for those people with attitudes that are only mildly opposed to different cultures, practicing tolerance, acceptance or inclusion could be new behaviours that require purposeful learning. The good-guy

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

liberalism overlooks the impact of cultural background and simplifies the process of cultural adjustment. Such a fallacy should be minimized in cultural competence research.

Conclusion

As culture involves almost every aspect of people’s lives, the process of becoming proficient in another culture is often chaotic, unstructured, and emotional. In the field of cultural competence, some studies strongly advocate acceptance and respect toward the other culture. However, in practice, the real challenge lies in the fact that even when people determine to do so, they still carry their own cultural baggage which could naturally generate confused, conflicted, and frustrated emotions. Therefore, while a great number of cultural studies have aimed at developing models and solutions to conquer the individuals’ frustration, confusion, and mistakes, they have paid little attention to the negative. This article calls on future research to examine participants’ negative feelings and experiences more deeply while within the intercultural environment. Stepping into the core of cultural conflicts and touching the face of these difficulties can help cultural researchers and practitioners to further understand how these individuals, little by little, become culturally competent. In a cross-cultural context, the problems themselves can provide clues for solutions, and negative experiences may also include positive insights.

In HRD, ‘learning is a central phenomenon in theories of complexity, although learning is typically implied rather than specifically explicated’ (Yorks and Nicolaides, 2006, p. 144). This statement can be applied to the learning process of cultural competence. To become familiar with another culture requires a great amount of implied and chaotic learning. Further studies can invite expatriates to describe their hectic adjustment, unexpected failures and unsolved problems and to explore how these experiences affect their cultural understanding in varied aspects, including local context, work strategies or even their self identification. Through examining not only positive but also negative intercultural experiences, HRD researchers and practitioners will have more opportunities to touch the complexity and step closer to the reality of cultural interaction.

References

Anderson, W. T. (1990) Reality isn’t what it used to be (San Francisco: Harper & Row).

Bazaldua, O. V. and Sias, J. (2004) Cultural competence: A pharmacy perspective, Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 17(3), pp. 160 – 6.

Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E. and Ananeh-Firempong II, O. (2003) Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care, Public Health Reports, 118(4), pp. 293 – 302.

Bjerneld, M., Lindmark, G., Diskett, P. and Garrett, M. J. (2004) Perceptions of work in humanitarian assistance: Interviews with returning Swedish health professionals, Disaster Management & Response, 2(4), pp. 101 – 8.

Caffarella, R. and Merriam, S. B. (2000) Linking the individual learner to the context of adult learning, in: A. Wilson and E. R. Hayes (Eds) Handbook of adult and continuing education, pp. 55 – 70 (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass).

Campinha-Bacote, J. (1998) The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services, 3rd edn (Cincinnati, OH: Transcultural CARE Associates).

Downloaded By: [Chang, Wei-Wen] At: 02:13 12 June 2007

Campinha-Bacote, J. (2002) Cultural competence in psychiatric nursing: Have you ‘ASKED’ the right questions? Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 8(6), pp. 183 – 7.

Cross, T. (2001) Cultural competence continuum. Available online: http://www.nysccc.org/T-Rarts/ CultCompCont.html (accessed 22 October 2004).

Dana, R. H., Aguilar-Kitibutr, A., Diaz-Vivar, N. and Vetter, H. (2002) A teaching method for multicultural assessment: Psychological report contents and cultural competence, Journal of Personality Assessment, 79(2), pp. 207 – 15.

Eder, D. and McClusky, A. T. (1996) Teaching across the barriers: The classroom as site of transformation, Transformations, 7(1), p. 37.

Forster, N. (2000) Expatriates and the impact of cross-cultural training, Human Resource Management Journal, 10(3), pp. 63 – 78.

Green-Hernandez, C., Quinn, A. A., Denman-Vitale, S., Falkenstern, S. K. and Judge-Ellis, T. (2004) Making nursing care culturally competent, Holistic Nursing Practice, 18(4), pp. 215 – 18.

Harris, S. (2006) Disasters and dilemmas: aid agency recruitment and HRD in post-tsunami Sri-Lanka, Human Resource Development International, 9(2), pp. 291 – 8.

Lister, P. (1999) A taxonomy for developing cultural competence, Nurse Education Today, 19(4), pp. 313 – 18.

MacNaughton, N. (2002) Cultural competence in nursing: Foundation or fallacy? Nursing Outlook, 50(5), pp. 181 – 6.

McFarland, J. R. (1996) Perspectives of United States expatriates in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France on expatriation and the role of their sponsoring organizations. Academy of HRD Conference Proceedings, Minneapolis, MN, 29 February – 3 March.

McPhatter, A. R. (1997) Cultural competence in child welfare: What is it? How do we achieve it? What happens without it? Child Welfare, 76, pp. 255 – 78.

Mendenhall, M. E. and Stahl, G. K. (2000) Expatriate training and development: Where do we go from here? Human Resource Management, 39(2,3), pp. 251 – 65.

Okeefe, T. (2003) Preparing expatriate managers of multinational organizations for the cultural and learning imperatives of their job in dynamic knowledge-based environments, Journal of European Industrial Training, 27(5), pp. 233 – 43.

Papadopoulos, R. (2003) The Papadopoulos, Tilki and Taylor model for the development of cultural competence in nursing, Journal of Health, Social and Environmental Issues, 4(1). Available online: http:// www.mdx.ac.uk/www/rctsh/modelc.htm (accessed 1 April 2005).

Pfeiffer, J. (2003) International NGOs and primary health care in Mozambique: the need for a new model of collaboration. Social Science and Medicine, 56(4), pp. 725 – 38.

Rankis, O. E. and Beebe, S. A. (1982) Expatriate executive failure: An overview of the underlying causes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (68th), Louisville,

KY, 4 – 7 Nov.

Rao, A., Southard, S. and Bates, C. (2005) Cross-cultural conflict and expatriate manger exploratory study, Technical Communication, 52(1), p. 106.

Selmer, J. and Leung, A. S. M. (2002) Career management issue of female business expatriates, Career Development International, 7(6), pp. 348 – 58.

Stahl, G. K., Miller, E. L. and Tung, R. L. (2002) Toward the boundless career: A closer look at the expatriate career concept and the perceived implications of an international assignment, Journal of World Business, 37(3), pp. 216 – 27.

Suutari, V. and Burch, D. (2001) The role of on-site training and support in expatriation: Existing and necessary host-company practices, Career Development International, 6, pp. 298 – 311.

Suutari, V., Raharjo, K. and Riikkila, T. (2002) The challenge of cross-cultural leadership interaction: Finnish expatriates in Indonesia, Career Development International, 7(7), pp. 415 – 29.

Taylor, E. W. (1994) Intercultural competency: A transformative learning process, Adult Education Quarterly, 44(3), pp. 154 – 74.

Varner, I. I. and Palmer, T. M. (2005) Role of cultural self-knowledge in successful expatriation, Singapore Management Review, 27(1), pp. 1 – 25.

Yorks, L. and Nicolaides, A. (2006) Complexity and emergent communicative learning: An opportunity for HRD scholarship, Human Resource Development Review, 5(2), pp. 143 – 7.