Path of socialization and cognitive factors' effects on adolescents' alcohol

use in Taiwan

Chao-Chia Hung

a, Yi-Chen Chiang

b, Hsing-Yi Chang

c, Lee-Lan Yen

c,d,⁎

a

Department of Nursing, College of Wellbeing Science and Technology, Yuanpei University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, ROC bDepartment of Public Health, Chung Shan Medical University, Tai-Chung, Taiwan, ROC

c

Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes, Miaoli, Taiwan, ROC d

Institute of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

a b s t r a c t

a r t i c l e i n f o

Keywords: Adolescents Drinking behavior Social cognitive theory Path analysis

Objectives: The purpose of this study was to explore the direct and indirect effects of alcohol-related socialization factors and cognitive factors on adolescent alcohol use in a country with a low prevalence of drinking. Methods: Data were obtained from the 2006 phase of the Child and Adolescent Behaviors in Long-term Evolution (CABLE) project, at which time the study participants were in grade nine (aged 14–15 years). Data from 1940 participants were analyzed. The main study variables included the current alcohol use of each adolescent, alcohol expectations, alcohol refusal efficacy, alcohol use among parents and peers, attitudes of the parents toward underage drinking, and peer encouragement of drinking. Path analysis was conducted to examine whether parental and peer socialization factors had direct effects on adolescent alcohol use, or whether they acted indirectly via cognitive factors.

Results: Among the participants, 19.54% had used alcohol in the previous month. Path analysis demonstrated that father, mother and peer alcohol use directly influenced alcohol use in adolescents. Attitudes of mothers toward underage drinking, peer drinking and peer encouragement of drinking had indirect effects on adolescent alcohol use that were mediated by cognitive factors.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that alcohol-related socialization factors could directly influence adolescent drinking behavior and had indirect effects on alcohol use that were mediated by cognitive factors partially. Parents and peers play important roles in preventing adolescent alcohol use. Establishing appropriate alcohol expectations and strengthening alcohol refusal skills could aid in decreasing alcohol use in adolescents. © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is the key period in which alcohol use is initiated; the quantity of alcohol consumption increases, and drinking problems begin (Li, Duncan, & Hops, 2001). Studies have shown that a greater number of ninth grade students use alcohol compared to other grades (Kuo, Yang, Soong, & Chen, 2002; Li et al., 2001), which indicates that ninth graders are at high risk for developing alcohol-associated psychological, social or health problems.

Level of economic development influences drinking behavior. In the Western Pacific Region, although there is currently a low prevalence of drinking there is a high level of economic development coupled with strong promotion and marketing of alcoholic products (WHO, 2001, 2004). Research on underage drinking in northern Europe and the United States has demonstrated that the amount of alcohol consumed by adolescents has started to decline in these

countries (Donovan, 2007; Hibell et al., 2003). In contrast, alcohol intake in regions with traditionally lower alcohol consumption, such as East Asia and the Western Pacific region, has increased (WHO, 2004). Early attention to drinking problems in these countries could prevent an increase in the prevalence of harmful drinking behaviors. Cross-national comparisons have found that demographic factors associated with drinking behavior in the past month differ between developed and developing countries (Priscilla, Kenneth, Riyadh, & Nilen, 2007). To date the majority of research on drinking behavior has been conducted in high prevalence settings with much less research conducted in low prevalence countries. There is evidence that alcohol consumption and the prevalence of alcoholism has dramatically increased in the past 40 years in Taiwan (Yang, 2002). The prevalence of underage drinking is also increasing.Chou, Liou, Lai, Hsiao, and Chang (1999)found that the prevalence of alcohol use at least once every month in adolescents aged 13–18 years in Taiwan has increased from 13% in 1991 to 16.7% in 1996. The study of factors associated with adolescent drinking behavior in a country with a low drinking prevalence that is experiencing rapid economic develop-ment, such as Taiwan, is an important area of research. Results from

⁎ Corresponding author at: 17 Hsu-Chow Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan, ROC. Tel.: +886 2 3368062; fax: + 886 2 23917780.

E-mail address:leelan@ntu.edu.tw(L.-L. Yen).

0306-4603/$– see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.004

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Addictive Behaviors

this research will aid in the development of appropriate interventions in Taiwan and other low prevalence drinking countries.

Studies investigating adolescent drinking behavior in industrial-ized countries have found that parents and peers are the key individuals who influence adolescent drinking behavior. The behavior of parents and parental attitudes toward underage drinking influence drinking behavior in adolescents. Adolescents with parents who drink alcohol are more likely to drink alcohol themselves (Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006). In contrast, non-support of underage drinking by parents decreases the likelihood of alcohol use by adolescents (van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, & Dekovic, 2006; Yu, 2003). The drinking behavior of peers and peer encouragement to drink are important peer-related factors that influence drinking behavior in adolescents. The perceived number of classmates and close friends who drink is an important risk factor for adolescent drinking (Li, Barrera, Hops, & Fisher, 2002). Peers can increase the likelihood of alcohol use by adolescents through peer pressure or encouragement to drink (Simons-Morton, 2004). The influence of peers on alcohol consump-tion by adolescents has led to a rising prevalence of alcohol use by adolescents (Duncan et al., 2006), even in low prevalence drinking countries such as Taiwan (Yang, Yang, Liu, & Ko, 1998; Yeh, 2006).

Bandura (1986) states that the impact of the environment on behavior is mediated through cognition. Individuals receive environ-mental stimuli and internalize associated cognitions, which lead to the promotion or limitation of particular behaviors. It is possible that in addition to a direct effect on drinking behavior, parental and peer drinking can influence adolescent alcohol use indirectly via cognitive processes such as alcohol expectations and alcohol refusal efficacy (Nash, McQueen, & Bray, 2005; Young, Connor, Ricciardelli, & Saunders, 2006). The majority of research in this area has investigated the separate effects of individual cognitive factors on alcohol use. However,Young et al. (2006)suggest that the effects of alcohol expectations and alcohol refusal efficacy on the types of drinking behavior should be examined together. In general, alcohol expectations include both positive and negative characteristics (Cameron, Stritzke, & Durkin, 2003). Studies have shown that positive alcohol expectations can predict drinking behavior typology and drinking problems, whereas negative alcohol expectations appear to be less predictive of drinking behavior (Young et al., 2006; Zamboanga, Horton, Leitkowski, & Wang, 2006). Consequent-ly, it is not common for both types of alcohol expectations to be measured in studies examining the use of alcohol in adolescents.Leigh and Stacy (2004)state that because positive and negative outcome expectations share some common, associated factors, the incorporation of both expectancy types into modeling causes suppression effects that can unmask associations between a particular expectancy and alcohol use, thereby influencing the interpretation of the results. Therefore, they recommend that studies include both positive and negative outcome expectations.

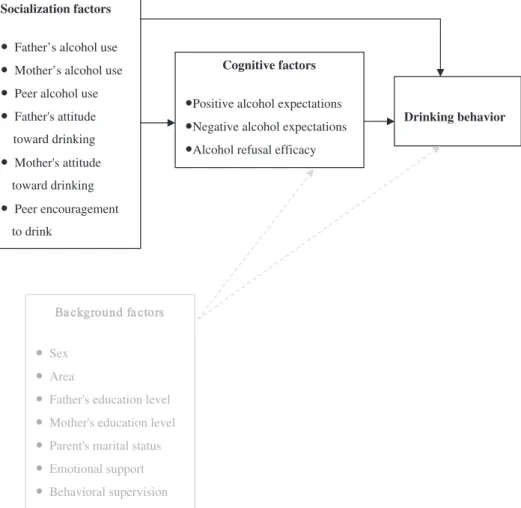

Although extensive research has been conducted on the effects of parental, peer and cognitive factors on drinking behavior, the mutual associations between these factors and their potential mediating effects remain unknown. To date, the majority of research has focused specifically on the effects of parental or peer drinking or another parental/peer factor on drinking behavior. However, in real life, there are no single factors that act alone to influence alcohol use. In the present study, we assumed that cognitive factors could be affected by peer and family factors, and we confirmed the individual contribution of different cognitive factors. The main aim of this study was to examine the relationship of parental and peer factors in influencing adolescent drinking behavior and to elucidate any novel cognitive mechanisms underlying these relationships. We constructed a theoretically driven multiple mediation model (seeFig. 1), and we hypothesized that parental and peer factors influence adolescent drinking behavior directly as well as functioning indirectly through associations with various cognitive factors that subsequently in flu-ence adolescent drinking behavior.

2. Method 2.1. Study sample

The data used in this analysis were obtained from the Child and Adolescent Behaviors in Long-term Evolution (CABLE) project (Yen, Chen, Lee, & Pan, 2002). The present study included the 2499 students in cohort 2 of the CABLE project who were in thefifth grade in 2002 at study commencement (when study participants were aged 10– 11 years) and in the ninth grade in 2006 (when study participants were aged 14–15 years). Participants with missing data were excluded resulting in afinal sample of 1940 students with complete data that were included in analyses (77.63% of the baseline sample). The chi-squared test was used to assess differences between the baseline andfinal samples in regards to demographic variables (sex, residential area, father's education level, mother's education level). No significant differences were found between the samples.

As the CABLE project is a school-based project, the clustering effect of schools for adolescent drinking behavior should be taken into account. As a result, we used GEE modeling with an exchangeable working correlation matrix to investigate the presence of clustering effects. The correlation coefficient of −0.003 from this modeling indicates that the correlation of ever drinking behaviors among adolescents within each school was very low. Therefore, we were able to ignore the clustering effect and analyze the data as an independent sample.

2.2. Measures

Variables included in the present study were selected based on social cognitive theory. Based on our study aims and a literature review, the dependent variable in our analyses was drinking behavior. After controlling for background variables that are known to be associated with alcohol consumption, including demographics, parental SES, and parenting behavior (Denton & Walters, 1999; Latendresse et al., 2008; Richter, Leppin, & Nic Gabhainn, 2006), we investigated the effects of behavioral modeling, social norms, social persuasion, and cognitive factors associated with positive and negative alcohol expectations and alcohol refusal efficacy on drinking behavior. Data on dependent and independent variables was obtained from the 2006 questionnaire apart from data on parenting behavior that was only collected in the 2004 questionnaire.

2.2.1. Drinking behavior

For a more comprehensive understanding of drinking behavior and to capture a greater range of variability in drinking typologies it is important to consider drinking frequency, drinking quantity, drinking environment and even types of alcohol consumed when measuring drinking behavior (Dawson, 1998; Gmel, Graham, Kuendig, & Kuntsche, 2006; Midanik et al., 1998; Pirkis, Irwin, Brindis, Patton, & Sawyer, 2003). However, the appropriate measure of drinking behavior also depends on the aim of the particular study. As adolescents are at a stage where they experiment with new behaviors, we considered‘ever drinking’ to be an important indicator of their drinking behavior. Ever drinking status was assessed by the single question“Have you ever drunk alcohol?” Responses were rated using a six-point scale that ranged from one (never) to six (every day in the last month). Based on these responses, we divided the ever-alcohol users into two groups: “Have not consumed alcohol in the past month” and “Have consumed alcohol in the past month”.

2.2.2. Parental alcohol use

Participants' perceptions of the alcohol use of their mother and father were measured using a six-point scale. Participants were asked “Does your father drink alcohol?” and “Does your mother drink alcohol?” Responses ranged from one (never) to six (every day in the

past month). These responses were then grouped into new categories as follows: 1) mother/father does not drink alcohol; and 2) mother/ father drinks alcohol (response scores 2 to 6).

2.2.3. Peer alcohol use

Participants' perceptions of peer drinking behavior were also assessed, differentiating between close friends and classmates. Participants were asked “How many of your close friends have drunk alcohol during the last year?” A five-point scale was used to evaluate the responses, which ranged from one (none) tofive (all of my friends). Scores for close friends and classmates were summed to obtain a total score that ranged from 2 to 10 points. A higher score indicated that participants perceived more peers drank alcohol. 2.2.4. Parental attitudes toward drinking

Participants' perceptions of their father's and mother's attitudes toward alcohol consumption were measured by asking“What is your father's attitude about your use of alcohol?” and “What is your mother's attitude about your use of alcohol?” Responses were scored on a five-point scale that ranged from one (he/she is extremely against it) tofive (he/she is extremely supportive of it). Scores ranged from 1 to 5 points. A higher score indicated a higher level of perceived support of drinking by mothers or fathers.

2.2.5. Peer encouragement to drink

Participants' perceptions of the frequency of encouragement to drink by close friends and classmates were assessed by asking“Have your close friends ever encouraged you to drink?” and “Have your classmates ever encouraged you to drink?” Responses were scored using a six-point scale that ranged from one (never) to six (every day

in the past month). Scores for close friends and classmates were summed to obtain an overall frequency of encouragement score for peers that ranged from 2 to 12 points. A higher score indicated a greater frequency of peer pressure to drink.

2.2.6. Positive alcohol outcome expectations

The questionnaire also assessed the participants' views about the positive effects of alcohol. Five questions were posed, including “Drinking alcohol makes people feel happy”, “Drinking alcohol makes me feel closer to my friends”, “Drinking alcohol helps me to feel brave and charismatic”, “Drinking alcohol helps me to sleep or get rid of pain”, “Drinking alcohol makes me feel more confident”. Responses were scored on a four-point scale that ranged from one (definitely not) to four (definitely). The scores for the five items were summed to obtain a total score that ranged from 5 to 20 points. A higher score indicated greater expectations of positive effects of alcohol. The Cronbach'sα for the scale was 0.83.

2.2.7. Negative alcohol outcome expectations

The questionnaire assessed the participants' views about the negative effects of alcohol by five questions including “Drinking alcohol makes people feel depressed”, “Drinking alcohol facilitates verbal or physicalfights with others”, “Drinking alcohol gives people a bad impression of you”, “Drinking alcohol makes you feel dizzy, nauseous or physically unwell”, and “Drinking alcohol makes people behave strangely”. Responses were scored on a four-point scale that ranged from one (definitely not) to four (definitely). The scores for thefive items were summed to obtain a total score that ranged from 5 to 20 points. A higher score indicated greater expectations of negative effects of alcohol. The Cronbach'sα for the scale was 0.83.

Socialization factors

Father’s alcohol use Mother’s alcohol use Peer alcohol use Father's attitude toward drinking Mother's attitude toward drinking Peer encouragement to drink Cognitive factors

Positive alcohol expectations Negative alcohol expectations Alcohol refusal efficacy

Drinking behavior

Ba ckground fa ctors

Sex Area

Father's education level Mother's education level Parent's marital status Emotional support Behavioral supervision

2.2.8. Alcohol refusal efficacy

The questionnaire assessed the level of confidence of the participants in their ability to refuse alcohol by five questions including:“When you are feeling bad, how confident are you that you will not drink alcohol?”, “When you feel uncomfortable, how confident are you that you will not drink alcohol?”, “When your elders are encouraging you to drink, how confident are you that you will not drink alcohol?”, “When classmates or friends are encouraging you to drink, how confident are you that you will not drink alcohol?”, and “When everyone around you is drinking, how confident are you that you will not drink alcohol?” Responses were scored on a five-point scale that ranged from one (absolutely no confidence) to five (completely confident). The scores for the five items were summed to obtain a score for self-efficacy that ranged from 5 to 25 points. A higher score indicated a greater degree of confidence in the ability to refuse alcohol. The Cronbach'sα for the scale was 0.92.

2.3. Data analysis

The distribution of independent, mediating and dependent vari-ables was described in terms of frequency distributions, means, percentages, standard deviations, maximums and minimums. Path analysis was used to test the multiple mediation model. The associated background, socialization and cognitive factors were entered into the model simultaneously as observed variables to investigate path relationships and path coefficients and standard errors (SE) were computed. More specifically, the present model assessed the effects of parental and peer factors on adolescent drinking behavior, both directly and indirectly through various cognitive factors to test the intermediary role of cognitive factors in the relationship between parental and peer factors and adolescent drinking. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 and LISREL 8.0 statistical software.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics and drinking behavior of the subjects Three hundred and seventy-nine students (19.54%) in the study sample had used alcohol in the previous month. The distribution of background characteristics in the study sample are shown inTable 1. Of the 1940 participants, 51.03% were male and 48.97% were female; 52.37% of the students lived in Taipei City, and 47.63% lived in Hsinchu County. The majority of parents were married and living together

(88.40%) and other marital arrangements were reported in only 11.60% of parents. The most frequent education level was a university degree and above for fathers (49.28%) and senior high school for mothers (49.07%).

3.2. Effects of drinking-related factors in the study sample

Table 2shows the direct and indirect effects of socialization factors on adolescent drinking behavior. With respect to overall effects, alcohol use by mothers (pb0.001), peer alcohol use (pb0.001) and peer encouragement to drink (pb0.05) were all significantly associated with drinking behavior in adolescents, with the strongest effect observed for peer alcohol use. We also found that alcohol use by fathers (pb0.05), alcohol use by mothers (pb0.001), and peer alcohol use (pb0.001) had significant direct positive relationships with drinking behavior, with the strongest direct effect observed for peer alcohol use.

Although no direct relationship between the attitudes of mothers toward drinking and alcohol use among the study participants was observed, the attitudes of mothers toward drinking was the only variable that demonstrated a significant indirect association with adolescent alcohol use (pb0.01).

Table 3shows the path coefficients for the effects of socialization factors and cognitive factors on adolescent drinking behavior. We found that cognitive factors were independently associated with peer and maternal factors and with alcohol use in adolescents. Negative alcohol expectations (pb0.001) and alcohol refusal efficacy (pb0.001) were negatively associated with adolescent alcohol use. The attitudes of mothers toward drinking were associated with both positive and negative alcohol expectations, with the strongest association observed for negative alcohol expectations (pb0.01). Peer alcohol use (pb0.01) and peer encouragement to drink (pb0.01) were both positively associated with positive alcohol expectations. Peer encouragement to drink was also negatively associated with alcohol refusal efficacy (pb0.01). These findings demonstrate that out of the three cognitive factors, positive alcohol expectations mediate the effects of maternal and peer factors on adolescent alcohol use. Negative alcohol expectations mediate the effect of maternal attitudes toward drinking on adolescent alcohol use, and alcohol refusal efficacy mediates the effect of peer encouragement to drink on adolescent alcohol use.

4. Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of alcohol use by parents, the attitudes of parents toward underage drinking, peer alcohol use and peer encouragement to drink on drinking behavior in adolescents in a country with a low prevalence of drinking. In addition to direct effects, we investigated the presence of any indirect effects of these variables on adolescent drinking behavior that are mediated by cognitive factors. We found that alcohol-related socialization factors could directly influence adolescent drinking behavior and had indirect effects on alcohol use that were mediated by cognitive factors partially.

Martino, Collins, Ellickson, Schell, and McCaffrey (2006) have demonstrated that alcohol use by peers and other adults is associated with attitudes and positive expectations of minors toward drinking. However, we found that when parental attitudes, number of peers using alcohol, peer encouragement to drink and individual cognitive factors were included in a path analysis model, parental modeling of alcohol use did not demonstrate a significant indirect relationship with adolescent alcohol use mediated by cognitive factors. The attitudes of mothers toward underage drinking only had indirect effects on adolescents' alcohol use that were mediated by positive and negative alcohol expectations. These discrepant results demonstrate the complex mechanisms that underlie drinking behavior.

Table 1

Background characteristics of the study sample.

Characteristic n (%) Mean (SD) Sex: Male 990 (51.03) Female 950 (48.97) Residential area: Taipei city 1016 (52.37) Hsinchu county 924 (47.63)

Parent's marital status:

Married and living together 1715 (88.40)

Other 225 (11.60)

Father's education level:

Junior high school and below 296 (15.26)

Senior high school 688 (35.46)

University and above 956 (49.28)

Mother's education level:

Junior high school and below 304 (15.67)

Senior high school 952 (49.07)

University and above 684 (35.26)

Parenting behavior (score range):

Level of emotional support (6–24 points) 16.42 (4.88) Level of behavioral supervision (3–16 points) 10.96 (3.12)

We found that mother's and father's alcohol use only had direct effects on alcohol use by adolescents. This result indicates that alcohol use in adolescents develops mainly through mimicking parental behavior, and therefore, parents are important role models for decreasing adolescent alcohol use. Research has demonstrated that parents who set rules limiting alcohol consumption can delay the initiation of adolescent drinking (Li et al., 2001; Simons-Morton, 2004; van der Vorst et al., 2006). We found that when controlling for the mother's and father's alcohol use, the attitudes of mothers had a more significant association with adolescent alcohol use. In particular, we found that the attitudes of mothers acted via alcohol expectations to influence adolescent drinking behavior. It is possible that the attitudes of mothers had a greater effect on adolescent drinking behavior due to the greater level of interaction between adolescents and their mothers compared to their fathers. Alterna-tively, this result could be explained by a stronger emotional bond between adolescents and their mothers. It is possible that mothers who do not support adolescent drinking influence drinking behavior by expressing negative opinions about alcohol. Bandura (1986)

investigated the influence of chance encounters on attitudes and found that the ideals and values of an individual determine whether they will accept the influence of the social environment on their behavior. Adolescents with mothers who do not support drinking internalize non-drinking values. Consequently, when they encoun-ter peers who drink or situations involving alcohol consumption, they are better equipped to maintain non-drinking behavior. As the influence of peers increases during adolescence, the non-support of drinking by mothers is an important defense against alcohol use by adolescents.

The majority of alcohol consumed by adolescents is obtained from peers (Harrison, Fulkerson, & Park, 2000). We found that peer encouragement to drink was significantly associated with adolescent drinking behavior, which is consistent with the findings of other studies (Duncan et al., 2006). Our results showed that the relationship between peer pressure to drink alcohol and adolescent drinking behavior was mediated by alcohol refusal efficacy. Moreover, peer

pressure to drink alcohol was not associated with alcohol outcome expectations. In other words, whether adolescents are influenced to drink alcohol through peer pressure does not depend on their attitudes toward the effects of alcohol but rather on whether they possess confidence in their ability to refuse their peers. Peer pressure can be difficult to resist. As indicated by previous research, the greater the confidence in the ability to refuse alcohol in various situations, the lower is the likelihood that adolescents will drink alcohol (Ma, Zhang, & Johnston, 2003; Yeh, 2006). Therefore, to reduce the influence of peers, it is important to facilitate alcohol refusal skills in adolescents. We found that the effects of peer factors were stronger compared to parental factors with respect to both direct effects on alcohol use and the total combined direct and indirect effects. This result indicates that peers have a greater influence on adolescents than do parents, which supportsfindings reported byNash et al. (2005). In addition, we found that all peer-related variables were associated with positive alcohol expectations. Evidently, adolescents are likely to view the behavior of their peers in a positive light. To a ninth grader, peers provide strong social support and emotional closeness. Adolescents readily identify with and mimic the behavior of their peers, and therefore, the presence of a large number of peers who drink increases the likelihood of adolescent alcohol use. As a result, decreasing alcohol use by peers is an important intervention strategy.

There is ample evidence (Ma et al., 2003; Zamboanga et al., 2006) that positive alcohol expectations can predict drinking behavior typologies and drinking problems, whereas negative alcohol expec-tations are less strongly predictive of drinking behavior. In contrast, we found that although positive alcohol expectations were associated with peer and maternal factors, drinking behavior in adolescents was significantly associated with negative rather than positive alcohol expectations, after adjusting for a comprehensive list of other factors.

Dunn and Goldman (1998)state that positive alcohol expectations are better at predicting the drinking behavior of adolescents who consume large volumes of alcohol. In contrast, the drinking behavior of adolescents who consume small quantities of alcohol is associated with negative alcohol expectations. Therefore, the relatively low alcohol consumption in our sample could explain why negative alcohol expectations were predictive of drinking behavior in our study. Moreover, according toFromme and D'Amico (2000), positive alcohol expectations are more sensitive in predicting the quantity of alcohol consumed. However, in the present study, we only measured the prevalence of alcohol use and not the quantity of alcohol ingested, which could have contributed to our failure to detect a significant effect of positive alcohol expectations. Our study supportsfindings that perceived negative outcomes from drinking are important factors in influencing the decision of adolescents to abstain from drinking alcohol. Therefore, discussion with adolescents about the negative effects that can be expected from alcohol use could decrease their alcohol consumption.

Table 2

Direct and indirect effects of socialization factors on adolescent alcohol use. Variable Total direct effect Total indirect effect Total effect

Father's alcohol use 0.09⁎ 0.01 0.08

Mother's alcohol use 0.19⁎⁎⁎ 0.00 0.19⁎⁎⁎

Peer alcohol use 0.22⁎⁎⁎ 0.01 0.23⁎⁎⁎

Father's attitudes 0.08 −0.01 0.07 Mother's attitudes 0.13 0.05⁎⁎ 0.19 Peer encouragement 0.10 0.04 0.14⁎ ⁎ pb0.05 (Z-score≥1.96). ⁎⁎ pb0.01(Z-score≥2.58). ⁎⁎⁎ pb0.001(Z-score≥3.29). Table 3

Path coefficients for the effects of socialization factors and cognitive factors on adolescent alcohol use behavior.

Variable Positive alcohol expectations Negative alcohol expectations Alcohol refusal efficacy Alcohol use

Father's alcohol use 0.07 0.06 0.02 0.09⁎

Mother's alcohol use 0.02 0.04 −0.02 0.19⁎⁎⁎

Peer alcohol use 0.11⁎⁎ 0.03 −0.09 0.22⁎⁎⁎

Father's attitudes −0.06 0.01 0.08 0.08

Mother's attitudes 0.17⁎ −0.21⁎⁎ −0.15 0.13

Peer encouragement 0.18⁎⁎ 0.02 −0.28⁎⁎ 0.10

Positive alcohol expectations 0.01

Negative alcohol expectations −0.15⁎⁎⁎

Alcohol refusal efficacy −0.14⁎⁎⁎

⁎ pb0.05 (Z-score≥1.96). ⁎⁎ pb0.01(Z-score≥2.58). ⁎⁎⁎ pb0.001(Z-score≥3.29).

4.1. Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Because underage drinking is illegal behavior and the data were obtained by self-report, it is possible that drinking behavior was underestimated in the present study. However, because the CABLE project has been running for 6 years, we believe that the trusting relationships built between participants and study personnel over this period aided in the collection of valid data. Moreover, there was no specific publicity regarding the research on substance use behavior during data collection. A further limitation of our study is that our sample excluded adolescents who had dropped out of school, and therefore, our results are only generalizable to adolescents who are currently enrolled in school. Finally, another limitation of the present study was the use of only a general question“have you ever drunk alcohol” to measure adolescent alcohol use. Although drinking quantity and drinking patterns are associated with health problems and social factors that are worthy of attention, compared to non-drinkers adolescents who consume alcohol are more likely to consume excessive quantities of alcohol and have poorer quality of life once they reach adulthood (Chen & Storr, 2006; Englund, Egeland, Oliva, & Collins, 2008). Moreover, as the sample used for the present study had a relatively low consumption of alcohol and are from a culture where drinking in adolescence is not common, we considered it more appropriate to use ever consumption of alcohol to represent drinking behavior. Future research could further investigate factors associated with drinking frequency, drinking quantity and experiences of intoxication in Taiwanese adolescents. Longitudinal analyses would enable confirmation of whether socialization factors and cognitive factors lead to particular drinking behaviors.

4.2. Implications for prevention

Based on the present results, we propose the following recom-mendations: health and educational organizations should address the problem of adolescent drinking by implementing preventive strate-gies that delay the initiation of alcohol use and decrease the quantity of alcohol consumed. These strategies should encourage a reduction of drinking by parents and peers to establish non-drinking norms and promote the non-support of drinking by mothers. Another important strategy is to strengthen alcohol refusal skills, in particular the ability to resist pressure from peers to drink. Finally, it is important to develop intervention strategies that aim to establish appropriate alcohol expectations.

Role of funding sources

Funding for this study was provided by National Health Research Institute (NHRI) Grant HP-090-SC03. The NHRI had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

All authors participated in the design of the study, and read and approved thefinal manuscript. CCH completed data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript; YCC and HYC were involved in critical revision of the manuscript; LLY contributed to data interpretation, and provided data analysis advice.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Cameron, C. A., Stritzke, W. G., & Durkin, K. (2003). Alcohol expectancies in late childhood: An ambivalence perspective on transitions toward alcohol use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 44(5), 687−698. Chen, C. Y., & Storr, C. L. (2006). Alcohol use and health related quality of life among

youth in Taiwan. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 752e9-e16.

Chou, P., Liou, M. Y., Lai, M. Y., Hsiao, M. L., & Chang, H. J. (1999). Time trend of substance use among adolescent students in Taiwan, 1991–1996. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 98(12), 827−831.

Dawson, D. A. (1998). Measuring alcohol consumption: Limitations and prospects for improvement. Addiction, 93(7), 965−968.

Denton, M., & Walters, V. (1999). Gender differences in structural and behavioral determinants of health: An analysis of the social production of health. Social Science & Medicine, 48(9), 1221−1235.

Donovan, J. E. (2007). Really underage drinkers: The epidemiology of children's alcohol use in the United States. Prevention Science, 8(3), 192−205.

Duncan, S. C., Duncan, T. E., & Strycker, L. A. (2006). Alcohol use from ages 9 to 16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81(1), 71−81.

Dunn, M. E., & Goldman, M. S. (1998). Age and drinking-related differences in the memory organization of alcohol expectancies in 3rd-, 6th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(3), 579−585. Englund, M. M., Egeland, B., Oliva, E. M., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Childhood and

adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction, 103(Suppl 1), 23−35. Fromme, K., & D'Amico, E. J. (2000). Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome

expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14(2), 206−212.

Gmel, G., Graham, K., Kuendig, H., & Kuntsche, S. (2006). Measuring alcohol consumption—should the ‘graduated frequency’ approach become the norm in survey research? Addiction, 101(1), 16−30.

Harrison, P. A., Fulkerson, J. A., & Park, E. (2000). The relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Preventive Medicine, 31(1), 39−48.

Hibell, B., Andersson, B., Bjarnason, T., Ahlström, S., Balakireva, O., Kokkevi, A., et al. (2003). The ESPAD report 2003: Alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries. Available at: http://www.sedqa.gov.mt/pdf/information/ reports_intl_espad2003.pdfAccessed August 4, 2008.

Kuo, P. H., Yang, H. J., Soong, W. T., & Chen, W. J. (2002). Substance use among adolescents in Taiwan: associated personality traits, incompetence, and behavioral/ emotional problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 67(1), 27−39.

Latendresse, S. J., Rose, R. J., Viken, R. J., Pulkkinen, L., Kaprio, J., & Dick, D. M. (2008). Parenting mechanisms in links between parents' and adolescents' alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(2), 322−330. Leigh, B. C., & Stacy, A. W. (2004). Alcohol expectancies and drinking in different age

groups. Addiction, 99(2), 215−227.

Li, F., Barrera, M., Jr., Hops, H., & Fisher, K. J. (2002). The longitudinal influence of peers on the development of alcohol use in late adolescence: A growth mixture analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25(3), 293−315.

Li, F., Duncan, T. E., & Hops, H. (2001). Examining developmental trajectories in adolescent alcohol use using piecewise growth mixture modeling analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(2), 199−210.

Ma, X., Zhang, Y., & Johnston, M. (2003). Effects of school experience on substance use among Canadian children: The power of the circle of friends. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 2, 143−164.

Martino, S. C., Collins, R. L., Ellickson, P. L., Schell, T. L., & McCaffrey, D. (2006). Socio-environmental influences on adolescents' alcohol outcome expectancies: A prospective analysis. Addiction, 101(7), 971−983.

Midanik, L. T., Rehm, J., Makela, K., Kubicka, L., Greenfield, T. K., & Dawson, D. A. (1998). Comments on Dawson's measuring alcohol consumption: Limitations and prospects for improvement. Addiction, 93(7), 969−977.

Nash, S. G., McQueen, A., & Bray, J. H. (2005). Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(1), 19−28.

Pirkis, J. E., Irwin, C. E., Jr., Brindis, C., Patton, G. C., & Sawyer, M. G. (2003). Adolescent substance use: Beware of international comparisons. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(4), 279−286.

Priscilla, R., Kenneth, R., Riyadh, O., & Nilen, K. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of substance use among high school students in South Africa and the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 97(10), 1859−1864.

Richter, M., Leppin, A., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (2006). The relationship between parental socio-economic status and episodes of drunkenness among adolescents: Findings from a cross-national survey. BMC Public Health, 6, 289−297.

Simons-Morton, B. (2004). Prospective association of peer influence, school engage-ment, drinking expectancies, and parent expectations with drinking initiation among sixth graders. Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 299−309.

van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C., Meeus, W., & Dekovic, M. (2006). The impact of alcohol-specific rules, parental norms about early drinking and parental alcohol use on adolescents' drinking behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(12), 1299−1306.

WHO (2001). Global status report: Alcohol and young people. Available at:http:// whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.1.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2008. WHO (2004). Global status report on alcohol. Available at:http://www.who.int/ substance_abuse/publications/global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2008.

Yang, M. J. (2002). The Chinese drinking problem: A review of the literature and its implication in a cross-cultural study. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 18(11), 543−550. Yang, M. S., Yang, M. J., Liu, Y. H., & Ko, Y. C. (1998). Prevalence and related risk factors of

licit and illicit substances use by adolescent students in Southern Taiwan. Public Health, 112(5), 347−352.

Yeh, M. Y. (2006). Factors associated with alcohol consumption, problem drinking, and related consequences among high school students in Taiwan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 60(1), 46−54.

Yen, L. L., Chen, L., Lee, S. S., & Pan, L. Y. (2002). Child and adolescent behavior in long-term evolution (CABLE): A school-based health lifestyle study. Promotion & Education Supplement, 1, 33−40.

Young, R. M., Connor, J. P., Ricciardelli, L. A., & Saunders, J. B. (2006). The role of alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy beliefs in university student drinking. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41(1), 70−75.

Yu, J. (2003). The association between parental alcohol-related behaviors and children's drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69(3), 253−262.

Zamboanga, B. L., Horton, N. J., Leitkowski, L. K., & Wang, S. C. (2006). Do good things come to those who drink? A longitudinal investigation of drinking expectancies and hazardous alcohol use in female college athletes. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 229−236.