Experiences of living with a malignant fungating wound: a qualitative

study

Shu-Fen Lo, Wen-Yu Hu, Mark Hayter, Shu-Chuan Chang, Mei-Yu Hsu and Li-Yue Wu

Aims and objectives. The purpose of this study was to explore the experience of cancer patients living with a malignant fungating wounds.

Background. Malignant fungating wounds are caused by cancerous cells invading skin tissue. These wounds can then bleed, become malodorous and painful causing physical and psychological distress. However, little is know about how individuals experience these lesions.

Design. Qualitative.

Methods. Ten in-depth interviews were conducted with patients in one medical teaching centre in Taiwan. Data were subject to a thematic analysis informed by elements of grounded theory.

Results. Five key themes demonstrated an emerging model that offers an insight into how patients experience their wound. Firstly, ‘Declining physical well-being’ refers to the initial impact of the wound, this is linked to two further themes; ‘Wound related stigma’ and the ‘Need for expert help’. Another theme; ‘Strategies in wound management’ describes the initial, ineffective attempts by participants to manage their wound and the impact of professional help around wound management. This was linked to a fifth theme; ‘Living positively with the wound’ that reflected how patients adjusted to the presence of the wound – significantly influenced by the wound care they received.

Conclusion. This study contributes to the understanding we have of how patients experience living with such wounds. It sets out the clear need for early use of wound specialists as part of the multi-disciplinary oncology team.

Relevance to clinical practice. The results of this study provides a description of patient experiences that can help to guide nursing practice as well as an understanding of what a malignant fungating wound means to cancer patients and how it influences their lives.

Key words: cancer, nurses, nursing, patient experience, qualitative, wound care

Accepted for publication: 16 April 2008

Authors: Shu-Fen Lo, MSc, RN, CWCN, Lecturer, Department of Nursing, Tzu Chi College of Technology and Doctoral Program Student, School and Graduate Institute of Nursing, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; Wen-Yu Hu, PhD, RN, Associate Professor, School of Nursing Science, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; Mark Hayter, RGN, PhD, MSc, BA (Hons) Cert Ed, FRSA, Senior Lecturer in Nursing, Centre for Health and Social Care Studies and Service Development, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK; Shu-Chuan Chang, RPN, PhD, Director, Department of Nursing, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, and

Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan; Mei-Yu Hsu, BSN, RN, Wound Ostomy and Incontinence Nurse, Department of Nursing, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital, & Graduate Student, Graduate Institute of Nursing, Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan; Li-Yue Wu, BSN, RN, Wound Ostomy and Incontinence Nurse, Department of Nursing, Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital

Correspondence: Shu-Fen Lo, Tzu Chi College of Technology, School of Nursing, 880, Sec.2, Chien-kuo Road, Hualien, 970, R.O.C. Taiwan. Telephone: +886 3 857 2158.

Introduction

At the beginning of the 21st century, cancer is increasing in the ageing population and patients often have a greater life expectancy than they did 40 years ago (Payne et al. 2004). As people age and the incidence of cancer increases, it is essential to push the frontiers of oncology care to meet the symptom management needs of these patients. For many, cancer has become a slowly progressive, chronic disease – a change that brings with it particular challenges for oncology nurses (Hoskin & Makin 1998). This paper explores a relatively neglected aspect of cancer care – the issue of malignant fungating wounds (MFW), particularly how cancer patients experience living with these types of wounds and the importance of specialist care in reducing the physical, emotional and social distress they often cause.

Background

Patients with cancer that survive longer often develop a more extensive spread of their tumour, including spread to the skin (Schultz 2001). MFW are caused by malignant cells invading skin tissue and are particularly seen in end stage or ignored cancer. If untreated the wound will progressively invade and destroy adjacent tissue and can also metastasise to other tissues (Bird 2000, Bryant 2000). MFW typically present as a cauliflower shaped lesion but also as an ulcerated area, presenting as a shallow crater, they may also expand further to form a sinus or fistula (Collier 1997, Haisfield-Wolfe & Rund 1997, Wilson 2005). Five to ten percent of patients with metastatic disease experience skin involvement which usually occurs during the last 6–12 months of life (Lo et al. 2006). Approximately 62% of MFW originate from breast cancer, followed by head and neck cancer (24%), genitals and back cancers (3%) and cancers of other areas (8%) (Clark 1992, Naylor 2002).

The adverse impacts of such lesions patients are numerous and typically include the physical, psychological and social. The literature on this topic is limited, but when explored, physical symptoms such as malodour, leakage, pain, oedema and bleeding are described by patients (Schulz et al. 2002, Wilkes et al. 2003, Piggin & Jones 2007). Emotional problems are often experienced, often relating to the fear and anxiety of leakage or malodour from the wound – this can also lead to social withdrawal and difficulties in family relationships (Lund-Nielsen et al. 2005, Piggin & Jones 2007). Studies also report that MFW symptom management provides challenges for nurses in oncology and palliative care settings (Haisfield-Wolfe & Rund 2002). The literature also reveals that oncology nurses often lack appropriate in-depth

knowledge about effectively managing MFW (Wilkes et al. 2003). This is particularly the case in Taiwan.

High quality MFW patient care is not easily achieved in Taiwan because there are only eight internationally certified wound therapists in practice there. Furthermore, there are no comprehensive wound training programs in Taiwan. How-ever, the prevalence rates of cancer continue to grow. In Taiwan, Cancer affects 1Æ5 million Taiwanese people and the numbers of patients presenting with MFW is becoming an increasingly common challenge for oncology services. (Department of Health 2007). Lo et al. (2006) conducted a retrospective, descriptive survey of patients with MFW in Taiwan between January 2002–March 2006. A total of 70 patients were identified (46 male, 24 female). The locations of the MFW were varied: head and neck 36 (51Æ4%), breast 13 (18Æ6%), urogential 6(8Æ6%) haematological three (4Æ3%) soft tissue sarcoma three (4Æ3%) and others nine (12Æ0%) (Lo et al. 2006). Patients also had to live with these wounds for some considerable time with the average time between wound formation and death being 12Æ56 months (Lo et al. 2006).

This study sets out to provide some key information about Taiwanese patients’ experiences of living with a MFW to help improve understanding and enhance care for this group of patients. Little is known generally about how patients experience these types of wounds and there have been no studies addressing the experience of Taiwanese people who have a MFW. Furthermore, no current conceptual models exist for MFW experiences in cancer patients. This study, therefore, aims to provide a theoretical description of the trajectory patients undertake from the development of their wound through to the end stages of their illness.

Study aims

The study aimed to explore the experience of cancer patients living with a MFW, specifically seeking to describe:

1 How cancer patients experience living with a MFW; 2 How MFW impacts on the lives of participants;

3 The various processes and strategies participants employ to resolve their main concerns regarding the MFW.

Methodology

In keeping with these research questions, an exploratory qualitative study adopting a thematic analysis was used. The thematic analysis approach employed techniques of data analysis drawn from grounded theory methodology. Data collection and analysis was informed by the work of Charmaz (2000) who argues that the techniques used in

conventional grounded theory can also be used as pragmatic ‘tools’ for studies seeking to explore and describe social situations as well as research attempting to provide an explanatory grounded theory (Charmaz 2000: p. 510). Although this study is not presenting a ‘grounded theory’ as such, it is seeking to explore and understand a social phenomenon – the experience of living with a MFW. Therefore, some of the early data collection and analysis procedures in grounded theory can also make a useful contribution to a thematic analysis – particularly the manner in which early data is coded and placed into themes (Strauss & Corbin 1990). Indeed, several descriptions of thematic analysis share the ideas of line by line coding, developing labels for these and then subsequently placing these data segments into themes that describe the phenomena taking place (Aronson 1994, Joffe & Yardley 2004).

Participants

A purposive sampling procedure was used to recruit partic-ipants from a medical centre in east Taiwan. Particpartic-ipants were recruited from palliative care settings and the oncology out-patients clinic. The purposive sample was selected using the following criteria: (i) participants aged 18 or older; (ii) having a MFW present for longer than four weeks; (iii) absence of diagnosed mental health issues or confusion that would interfere with interviewing process; and (iv) having the ability to communicate in Chinese. Data collection began in February 2006 and was completed in December 2006 – a protracted timescale that was necessary because of the relative rarity of MFW in Taiwan.

A total of 10 patients were involved in the study. Three of the participants were widowed and two of were single while the remaining five were married. The age of participants ranged from 42–72, with a mean age of 54. Six were female and four were men. On average, they had been living with a MFW for 9Æ86 months (ranging from 3–24 months).

Ethical issues

The Chi-Zi Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the research protocol prior to the commencement of the research. The study was explained verbally to participants and they also received a written explanation. They were informed that participation was voluntary and they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were given the opportunity to review field notes that consisted of the researcher recording important issues or particularly emotive issues within each interview prior to the conclusion of interviews. They were also assured that published data would not include any identifying informa-tion. All participants signed a consent form and assurances of confidentiality were given.

Data collection

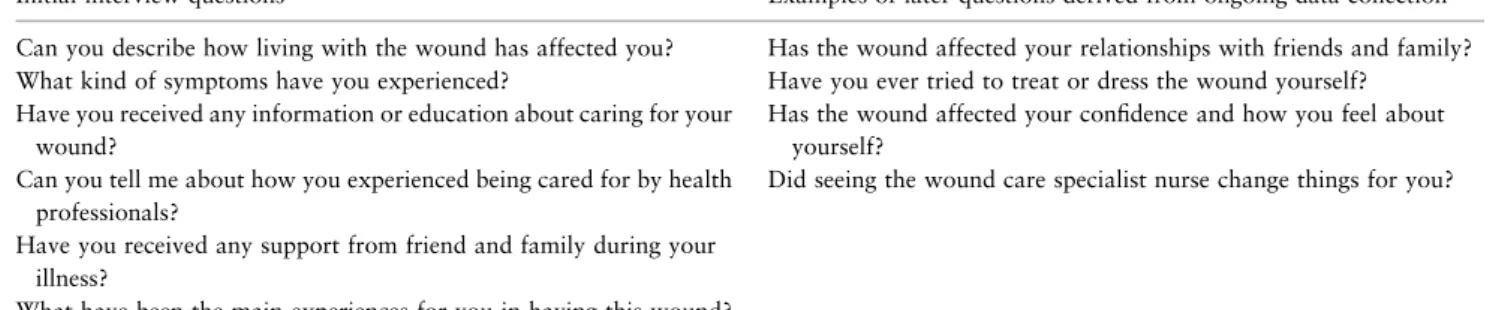

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews by a single researcher. An interview schedule was devised and piloted in one preliminary interview (the data from this interview were included in the study because of the success of the interview and also because of the scarcity of eligible patients). The interview schedule consisted of broad, open questions designed to encourage discussion that were developed by the research team informed by the existing literature base for MFW care. Initial questions about time of diagnosis and social circumstances were asked followed by a series of specific questions that were used as a guide for the interview. As each individual interview proceeded questions were used to clarify and encourage further discussion. As the data collection progressed more ques-tions were added to the overall interview guide – although these were intended to be used flexibly and when appro-priate (see Table 1 for questions used). A quiet area was used so that participants could reflect on their experiences and audio taping could be conducted. Field notes were also

Table 1 Interview questions

Initial interview questions Examples of later questions derived from ongoing data collection Can you describe how living with the wound has affected you? Has the wound affected your relationships with friends and family? What kind of symptoms have you experienced? Have you ever tried to treat or dress the wound yourself?

Have you received any information or education about caring for your wound?

Has the wound affected your confidence and how you feel about yourself?

Can you tell me about how you experienced being cared for by health professionals?

Did seeing the wound care specialist nurse change things for you? Have you received any support from friend and family during your

illness?

recorded to aid subsequent analysis allowing researchers to highlight seemingly important aspects of the interview and also to record any emotions expressed by patients. The audio tape-recorded interviews ranged from 30–60 minutes in length, with the average length being 45 minutes. Data were transcribed verbatim – translation into English was also undertaken.

Data analysis

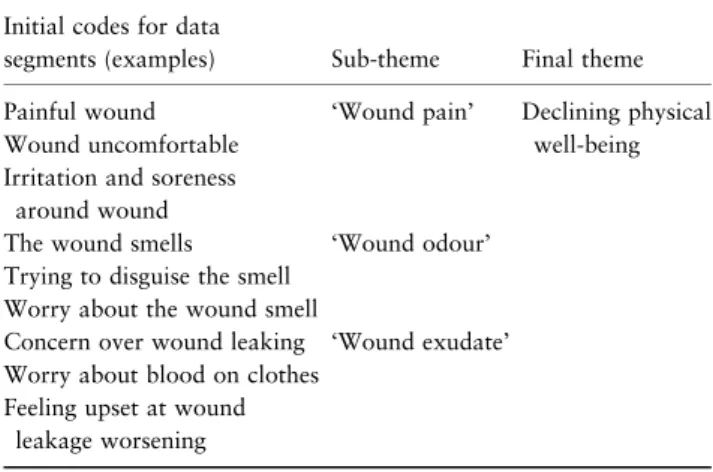

Data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach drawing upon the work of Charmaz (2000) and Strauss and Corbin (1994, 1998) but also informed by Aronson (1994) and Joffe and Yardley (2004). In this approach, data are initially combed for line-by-line segments that describe a particular issue within the informants’ narratives. This procedure is congruent with the technique of ‘open coding’ in grounded theory (Charmaz 2000). The data segments are then given initial labels that best fit the meaning attached to that part of the narrative (Charmaz 2000). As with grounded theory, these segments of data are then merged into more substantial clusters of data (or sub-themes) by a process that examines the data for patterns, links and commonalities. These larger data segments are then placed into larger themes that intend to present a ‘comprehensive picture of the collective experience’ (Aronson 1994: p. 21). Table 2 presents an example of how these initial data segments formed sub-themes and larger sub-themes. In addition, because the data collection period was protracted it enabled some preliminary analysis of the data to take place as data collection progressed. This process, although not as formal, mirrored the notion of the constant comparative method within grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin 1990, 1998) and allowed for some additional questions to be used in subsequent interviews (see Table 1).

Rigour

Several measures were adopted to enhance the trustworthi-ness of the data, drawn from procedures outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985). Member checking techniques allowed participants to comment on the accuracy of transcripts and emerging themes. This was achieved by discussing and explaining the findings with two participants (participants 1 & 2) towards the end of the study. Both remarked that they could identify with the themes and processes emerging from the study. Dependability was enhanced using a peer review coding process whereby members of the research team (SL and WH) sought to establish a consensus around emerging themes, a technique of trustworthiness in the development of a qualitative analysis identified by Lincoln and Guba (1985). As with most qualitative research, transferability is not tested here but is left to other researchers to test the findings in other cultures and care contexts.

Findings

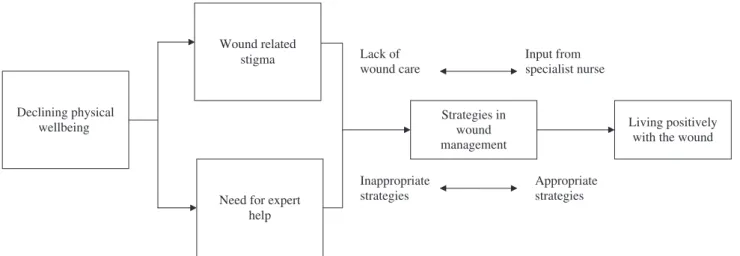

The thematic analysis of data resulted in the emergence of five themes that seem to describe how participants expe-rienced living with their MFW. The five themes were; ‘Declining physical wellbeing’, ‘Wound related stigma’, ‘Need for expert help’, ‘Strategies in wound management’ and ‘Living positively with the wound’. Furthermore, although a small study, the themes derived from this data may also tentatively describe a ‘journey’ participants undertake when living with a MFW. Further, research into the robustness of these themes could add credibility to this notion. A diagrammatic representation of this journey is provided in Fig. 1. The following sections describe the structure and content of these themes using paradigm extracts from the interview data.

Declining physical well being

Participants reported a gradual change in their physical wellbeing as their cancer and wound progressed. The development of the wound served as a starting point for a set of increasingly problematic physical symptoms. Wound odour was something all participants mentioned as an issue that caused them distress both physically and socially. Participant 4 explains how she tried to mask the wound odour:

Despite me using the perfume, it can’t cover the wound odour.

Participant 7 mentions the link between exudate and wound odour, despite him trying to manage the wound himself:

Table 2 Construction of ‘Declining physical well-being’ theme Initial codes for data

segments (examples) Sub-theme Final theme Painful wound ‘Wound pain’ Declining physical

well-being Wound uncomfortable

Irritation and soreness around wound

The wound smells ‘Wound odour’ Trying to disguise the smell

Worry about the wound smell

Concern over wound leaking ‘Wound exudate’ Worry about blood on clothes

Feeling upset at wound leakage worsening

I am still cleaning my wound, however the wound continues to produce green and purulent exudate.

Similarly, participant 2 describes how a leaking wound caused distress:

I always suffer from bleeding after a change of dressing or slight exercise, I don’t feel any improvement until the next day…I didn’t know that so much leaking from the wound would result in me always changing dressings.

In addition to malodour and wound leakage participants reported wound related pain as having a significant impact on their lives, for example:

My sleep and rest always break off because of slight to mild shooting and stabbing pain

Participant 9 had similarly problems saying:

I only eat soft cool noodles and bread, because those can decrease my mouth wound pain.

Wound related stigma

Closely related to the distress caused by the physical symptoms of the wound participants describe how the presence of the wound has significant psychological impact. The theme ‘Wound related stigma’ refers to the way in which participants felt socially isolated because of their wound. It describes how they felt embarrassed because of the odour and leakage from their lesion and sets out how they responded to this by socially isolating themselves:

I always stay home due to the wound leaking so much.

Participant 1 identifies how the wound has affected her confidence and body image:

Before developing the wound, I was quite confident about my appearance. Now, I am very ashamed and lose self-confidence, due to the malodour.

Participant 4 experienced similar feelings, remarking that although he feels people can understand his cancer diagnosis the wound is hard for others to accept:

I can tell everyone I got cancer, but I can’t share my wound, it is so horrible, not everyone can understand it.

Participants often remarked at how the presence of the wound affected their social behaviour, with them becoming progressively isolated from the outside world. For example, participant 1 says:

I don’t go too far away, because I need to frequently change my wound dressing and clothing; I always wear over neck jacket even though it’s hot. I think that this way I can prevent odour and exudates escaping from my wound.

Participant 4 also mentions how keeping the wound secret also extends to family members:

My mother and sister say they want to see my wound, but I don’t agree because the wound is so disgusting, I want them to keep a good impression of me.

Participants 3 remarked how the wound affects his decisions to travel out with his family:

Before the wound was present I would always travel with my family. Now, I worry about bleeding and leakage…I don’t travel any more.

Participant 7 described how he experienced other patients reactions to his wound whilst in hospital:

Strategies in wound management

Lack of Input from wound care stigma Wound related specialist nurse Appropriate strategies Inappropriate strategies Declining physical wellbeing

Need for expert help

Living positively with the wound

Another patient said they didn’t want to become ward-mate with me, because they saw my wound and smelled the odour…the wound made me feel so embarrassed.

Living with the wound also affected some family members, particularly those who become involved in helping to manage the wound, participant 5 says

I feel so sad and sorry about my daughter who can’t work because she needs to help me change my wound dressing.

Finally, in this section, some participants regarded the wounds presence as a constant reminder of their cancer and also of their terminal illness. A good example of this is the comments of Participant 8 who remarks:

I don’t want to die; however, this wound looks as if death is more and more near me. I can’t escape, I feel so distressed.

Need for expert help

In response to their ‘declining physical well being’ and ‘wound related stigma’ the participants attempted to take action to overcome it. Participants described how they expected help from specialists in the early stages of their illness. They particularly identified their needs included wound related information, pain relief and financial support for dressings. Unfortunately, they didn’t initially obtain appropriate wound related information from the medical care team.

Participant 1 mentioned that:

Before I met the wound specialist, no nurses told me how observe my wound and deal with it. I worried about this because I didn’t know what would happen to it [the wound].

Participant 2 had a similar lack of knowledge and support, remarking:

I am afraid of the wound bleeding, so I remove my dressing by shower and that takes at least 10–15 minutes.

Participant 10 mentions that he experienced almost constant pain from his wound before he received specialist care input:

Before I met the wound specialist I usually experienced moderate to strong pain even though I took analgesics.

Participant 4 describes how the lack of wound related information affected how he understood his wound and caused him anxiety:

I didn’t know that the wound would always bleed, have malodour and a lot of white coloured tissue? Is it slough? It is linked to my treatment or a sign of cancer cell spread?

Strategies in wound management

Before gaining appropriate specialist help the participants had attempted various strategies to self-manage their wound. These coping strategies came about as they strove to minimise the embarrassment and social isolation they were experienc-ing because of the wounds presence. However, often these attempts were ineffective or actually worsened the condition of their wound. For example, Participant 1 describes her attempts to disguise wound leakage:

I used toilet paper to cover my wound to avoid leakage.

Some of the strategies adopted could also be harmful to general health or the wound specifically, for example, Participant 5:

I restrict my water intake, then I can reduce pass urine, if urine leakage my wound dressing, I just remove outer dressing.

Participant 6 describes how her wound treatment was aimed at ‘curing’ the wound, clearly adopting a harmful practice:

I brush at my wound used baby toothbrush, I think that I can damage it then I can cure my wound.

Another example of this is participant 10’s attempts to treat her own wound:

I put hydrogel dressing on the wound edge, I didn’t want to cover it on centre of wound and I think that can help exudates pass through.

Social stigma also contributed to participants trying to self-manage their wounds. In this following extract Participant 4 describes concerns about health professionals seeing the wound:

I am very ashamed to expose my breast wound for a male physician; therefore I used traditional Chinese herb to put on the wound surface.

What emerged clearly from the data was the impact that eventual input by wound care specialist nurses had on the participants’ experiences. This input helped participants manage the wound physically by being taught cleaning and dressing techniques – this also involved being taught how to assess the wound bed and dress appropriately. Participants were also informed about the signs and symptoms of wound infection. Specialist nurse input also involved comprehensive pain assessment and a management strategy was employed. Participants also had access to fragrance therapy to manage wound malodour problems. This care resulted in appropriate wound care management taking place and participants clearly identified this as a significant change in their experience of living with the MFW. Participant 4 explained the way he felt:

When I used Aqucel-Ag to control wound infection, I noticed reduced wound odour and less pain’. ‘When I receive fragrance therapy, the drop of essential oil on my secondary dressing improved my emotion and improved my appetite.

Participant 1 reported similarly, saying:

When I used the foam dressing and Metronidazole it was so magical, I just change the dressing and don’t experience any more malodour.

Participant 8 described how the wound specialist helped him:

The wound specialist is always gentle when irrigating my wound by syringe, it makes me more comfortable. I don’t feel any pain after the wound dressing.

Participant 6 felt the same way, saying:

When I apply morphine gel on my oral wound surface, I can eat more and have a good sleep. I trust you and the wound related team, because you always pay attention to my problems and concerns.

What seems clear from this data is that the eventual input of the wound care specialist team significantly altered the trajectory these patients were on when living with their MFW. Access to sensitive, knowledgeable and skilled care made the participants feel much better about their wounds, an aspect reflected in the final category described in the grounded theory.

Living positively with the wound

This final theme describes how participants eventually became able to live more positively with their wound. This transition was closely related to them getting the information and care they required to manage their wound from the intervention of the wound care specialist nurse. This often involved participants receiving a combination of wound care advice, appropriate dressings and support for self-care. Participants described that they experienced positive wound outcomes such as improved wound bed condition, reduced pain and improved sleep quality, that enabled them to regain self-confidence. For example, after the specialist nurse taught him to care for his wound, participant 6 remarked that this would enable him to teach the home care nurse about the appropriate wound care he required:

I am very happy that I can go home, I hate to stay in hospital long term, if you didn’t help me by teaching district nurses to care for my wound, I think that the physician would not permit this.

Participant 7 said:

After I used this new dressing, the pain is much better, I have good sleep now.

Specialist nurse input also helped to alleviate some of the social discomfort reported by the participants earlier in their MFW experience. Participant 5 mention that now she had been helped to manage her wound and use appropriate dressings she felt much more able to travel with her family:

I went to Japan with my family at last week, because I know that how to observe my wound and choose a suitable wound dressing to cover it. That is a nice journey.

Participant 9 said:

When the odour had gone I felt I could touch other people with more confidence.

Specialist nurse help also had an impact on participants’ families. Participant 5 mentions how wound education helped her daughter to manage her care better:

When the wound specialist nurse teaching my daughter how to observe the wound bed and choose the correct dressings, I just needed to change the secondary dressing 1–2 times per day. I am very happy about this, because my daughter can go back her normal working life.

Finally, participant 1 summarises the impact of skilled care from the wound specialist nurses:

I think that the wound specialist is my angel, because she drives out my wound malodour and exudate. I was very pleased to meet her.

Discussion

Appropriate individual wound management strategies are crucial element in the MFW disease process. Ten cancer adults were interviewed about the MFW experience in this study. The study identified how MFW related symptoms affected almost every aspect of the participants’ lives. The data illustrates the pain and social stigma they experience – it also illustrates the impact that appropriate wound care can have on their sense of physical and emotional wellbe-ing. Lack of information initially in the wound process led to pain, social isolation and inappropriate wound manage-ment techniques. Specialist help addressed these problems and led to participants feeling more positive about their wound.

The general literature in oncology clearly identifies the importance of good symptom control in palliative/terminal care (Benzein & Berg 2005, Scanlon 2006). Symptom control is not only important for physical health – it improves an individuals self-esteem and restores some sense of purpose (Herth & Cutcliffe 2002). The MFW process

described in this study is often accompanied by a range of losses, particularly loss of body image, loss of self-esteem, loss of hope and loss of a normal daily life. The impact of these losses is exacerbated by the intentional withdrawal from normal social activity prompted by the stigma of the wound, findings that particularly resonate with the work of Piggin and Jones (2007). In this sense the wound is having a stigmata effect, the anxiety of being seen to be ill and disfigured clearly relates to Goffman’s (1963, 1967) work on stigma and social embarrassment and the desire individuals have to hide the outward signs of disease. The participants reactions in this study are also reflective of the intentional withdrawal from society by individuals affected by loss, anxiety and reduced self-esteem – in a sense the participants are grieving for their altered body image (Parkes & Markus 1998).

Participants in this study identified a need for informa-tion about their wound from medical staff involved in their care – this was initially lacking. This in turn led to participants trying to care for their own wound in numerous, sometimes, harmful ways. This seemed to occur out of desperation related to pain and also social embar-rassment. In this study, a lack of MFW knowledge and expertise led to the poor symptom control reported by participants. The literature does identify that specific symptom management is often a challenge for nurses in oncology and palliative care settings (Haisfield-Wolfe & Rund 2002). Numerous studies have reported that nurses find uncontrolled symptoms in cancer patients, particularly intractable pain and malodour, very stressful and frustrat-ing (Hatcliffe et al. 1996, Wilkes & Beale 2001). Unfor-tunately, in this study, a lack of wound training, lack of wound management skills and a lack of enough wound care guidelines in palliative care exacerbated this problem. Most nurse and clinicians initially involved in caring for the participants in this study seemed to develop their own individual approaches through trial and error, within environments that were not conductive to effective wound management. Care protocols that include the early inclu-sion of specialist nurse involvement in such cases are clearly needed in Taiwan.

One of the key improvements specialist nurse involve-ment had was the use of appropriate and effective wound assessment and dressings. The use of these dressings and patient education were clearly highlighted as important by participants. This aspect of the study reinforces a similar study by Lund-Nielsen et al. (2005) who interviewed 12 women with breast MFW in Denmark and describe how the women reported significant improvements in wound odour and leakage. Lund-Nielsen et al. (2005) also

highlighted the value of specialist nurse involvement in patient care as did Piggin and Jones (2007). The develop-ment of the nurse specialist role in tissue viability is an important consideration in providing quality care to patients with MFW.

What seems clear from this study and the others cited is that the management of MFW is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach to care. Care should be flexible and focus on the patient’s priorities, as well as the manage-ment and control of symptoms (Dowsett 2002). This approach is vital in ensuring that effective wound interven-tion succeeds in increasing patients’ physical and psychoso-cial well-being and reducing sopsychoso-cial isolation (Lund-Nielsen et al. 2005). Wound symptom control, social support, learning about wound management and meaningful engage-ment with skilled staff can empower MFW patients to live more positively with their condition. Wound therapists therefore play a powerful role in enhancing the quality of wound care when they develop trusting relationships and individualised nursing interventions to meet the needs of their patients. It is important that they are involved as early as possible in the care and management of individuals with MFW.

Limitations of the study

This was a small, exploratory study and participant numbers were small with data collection limited to one study setting only. Therefore, although providing some useful insights, generalised application of the findings to other populations requires caution. Further research in different clinical settings will add to the credibility of the findings reported in this study. In particular, further studies are needed to explore the robustness of the tentative links made between the themes and the description of a possible MFW ‘journey’ in this study. Further studies with more patients in other cultures and care settings may strengthen, amend or further develop our initial work in this field.

Conclusion

This study raises awareness of exactly how patients can feel living with such a wound and the impact upon daily living. This study strengthens the knowledge base of MFW by describing, from the point of view of cancer patients, what specialist nurse interventions can do to promote patients’ quality of life during the final stages of their illness. In doing so it also provides evidence about what kind of nursing action helps and supports the cancer patients suffering from a MFW. To improve patient care and

promote patient’s quality of life, the palliative multi-disci-plinary team not only should understand how to undertake a comprehensive assessment of MFW, but also need to add MFW management into training programs. In particular, focusing on interventions consisting of; communication, education, support and multi-disciplinary team working. Furthermore, this study outlines that the appropriately selected wound dressing can decrease MFW symptoms and relieve pain. Specialist wound care nurses can particularly help with this aspect of care.

Further research is needed to investigate in more detail those areas identified by this study. Studies could be usefully conducted to evaluate differences in wound dress-ing, wound management protocol and quality of life in patients with MFW. Wound related information plays a key role in the level of anxiety experienced by patients experiencing a MFW. Unfortunately, the majority of participants in this study initially experienced low levels of accurate information from medical professionals. This could be due to the relative scarcity of MFW in Taiwan. One way forward would be to establish an evidence –based MFW management protocol to help nurses manage MFW and provide quality of care for patients.

Author contributions

Study design: SL; WH; data collection and analysis: SL, MYH, MH; SCC; manuscript preparation: SL, WH, SCC, MYH, LYW, MH.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Tzu Chi College of Technology in Taiwan who funded research financial. We would also like to thank the participants in this research for openly sharing their MFW experiences.

References

Aronson J (1994) ‘A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis.’ The Qualitative Report 2 Spring. Available at: http://www. nova.edu/ssss/QR/BackIssues/QR2-1/aronson.html (accessed Au-gust 2007).

Benzein EG & Berg AC (2005) The level of and relation between hope, hopelessness and fatigue in patients and family members in palliative care. Palliative Medicine 19, 234–240.

Bird C (2000) Managing malignant fungating wounds. Professional Nurse 15, 253–256.

Bryant RA (2000) Acute & Chronic Wounds: Nursing Management, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis, MO, USA.

Charmaz K (2000) Ground theory: objective and constructivist methods. In Handbook of Qualitative Research (Denzin NK & Lincoln YS eds). Sage Publication, Thousands Oaks, CA, pp. 509– 535.

Clark L (1992) Journal of wound care nursing. Caring for fungating tumours. Nursing Times 88, 66–70.

Collier M (1997) The assessment of patients with malignant fungating wounds – a holistic approach: part 1. Nursing Times 93, S1–S4.

Department of Health, Taiwan, R.O.C., Executive Yuen, (2007) Health and Vital Statistics. Department of Health, Taipei. Dowsett C (2002) Malignant fungating wounds: assessment and

management. British Journal of Community Nursing 7, 394– 400.

Goffman E (1963) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Pendice-Hall, Inc, Englewood Ciffs.

Goffman E (1967) Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Beha-vior. Pantheon Books, New York.

Haisfield-Wolfe M & Rund C (1997) Malignant cutaneous wounds: a management protocol. Ostomy/Wound Management 43, 56–60 62, 64–66.

Haisfield-Wolfe M & Rund C (2002) Malignant cutaneous wounds: developing education for hospice, oncology and wound care nur-ses. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 8, 57–66. Hatcliffe S, Smith P & Daw R (1996) District nurses’ perceptions of

palliative care in the home. Nursing Times 92, 36–37.

Herth KA & Cutcliffe JR (2002) The concept of hope in nursing 3: hope and palliative care nursing. British Journal of Nursing 11, 977–984.

Hoskin P & Makin W (1998) Oncology for Palliative Medicine. Oxford University Press, London.

Joffe H & Yardley L (2004) Content and thematic analysis. In Re-search Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology (Marks DF & Yardley L eds). Sage, London, pp. 59–69.

Lincoln Y & Guba E (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA.

Lo SF, Hsu MY & Chang SC (2006) Clinic follow-up of patient with malignant fungating wounds in adults in Taiwan. Proceedings of the 16th Biennial Congress of the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists, abstract A180. Hong Kong Enterostomal Therapist Association, Hong Kong.

Lund-Nielsen B, Muller K & Adamsen L (2005) Malignant wounds in women with breast cancer: feminine and sexual perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing 14, 56–64.

Naylor W (2002) Malignant wounds: aetiology and principles of management. Nursing Standard 16, 45–56.

Parkes CM & Markus A (1998) Coping With Loss: Helping Patients and Their Families. BMJ, London.

Payne S, Seymour J & Ingleton C (2004) Palliative Care Nursing: Principles and Evidence for Practice. Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Piggin C & Jones V (2007) Malignant fungating wounds: an analysis of the lived experience. International Journal of Palliative Care 13, 384–391.

Scanlon C (2006) Creating a vision of hope: the challenge of pallia-tive care. Oncology Nursing Forum 33, 491–498.

Schultz VM (2001) The Development of a Malignant Wound Assessment Tool. PhD Thesis, University of Alberta, Canada.

Schulz V, Triska O & Tonkin K (2002) Malignant wounds: care-giver-determined clinical problems. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 24, 572–577.

Strauss A & Corbin J (1990) Basic of Qualitative Research: Ground Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publication, Thousands Oaks, CA.

Strauss A & Corbin J (1994) Ground theory methodology: An overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research (Danzin NK & Lincoln YS eds). Sage Publications, London, pp. 1–18.

Strauss A & Corbin J (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research. Tech-niques and Procedures for Developing Ground Theory, 2nd edn. Sage Publication, Thousands Oaks, CA.

Wilkes L & Beale B (2001) Palliative care at home: stress for nurses in urban and rural New South Wales, Australia. International Journal of Nursing Practice 7, 306–313.

Wilkes LM, Boxer E & White K (2003) The hidden side of nursing: why caring for patients with malignant malodorous wounds is so difficult. Journal of Wound Care 12, 76–80.

Wilson V (2005) Assessment and management of fungating wounds: a review. British Journal of Community Nursing 10, S28–S34.