Self-reported Sleep Disturbance of Patients

With Heart Failure in Taiwan

Hsing-Mei Chen4 Angela P. Clark 4 Liang-Miin Tsai4 Yann-Fen C. Chao

b Background: Western research studies have found that sleep disturbances reduced quality of life and daily functioning of patients with heart failure; however, information about sleep disturbance is lacking in Taiwanese people with heart failure.

b Objectives: The objective of this study was to investigate predictors of self-reported sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with heart failure. The hypothesis was that health-related quality of life (HRQOL) could have significant effect on sleep disturbances, after controlling for demographics, heart failure characteristics, and health-related characteristics. b Methods: A cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational design was used. A purposive sample of 125 participants was recruited from the outpatient departments of two hospitals located in southern Taiwan. Participants were interviewed individually to complete the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and Perceived Health Scale instruments. b Results: Self-reported sleep disturbances were prevalent (74%) among people with heart failure in Taiwan. Five predictors were identified using hierarchical multiple regres-sion analyses with forward methods, accounting for 26.9% of variance in sleep disturbances. They were education, New York Heart Association functional classification, perceived health, HRQOL social functioning, and physical symptoms. After controlling for demographics, heart failure characteristics, and health-related characteristics, the anal-ysis showed that two variables of HRQOL accounted for 9.8% of the variance in sleep disturbances.

b Discussion: The importance of ongoing screening for sleep disturbances in people with heart failure is highlighted based on the study findings about the prevalence of sleep disturbances among the participants in this study. Health-care providers must understand the often multifactorial nature of sleep disturbances to achieve a better and more effective management.

b Key Words: health-related quality of life&heart failure&sleep disturbance

H

eart failure (HF) is a chronic and lethal syndrome characterized with markedly declined heart function and high rates of hospitalization and mortality across theworld (Young, 2004). Symptom burden in HF causes devastating physical and psychosocial functioning and poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL). The major goals for HF treatment are to help patients achieve higher levels of HRQOL and to improve survival (Hadorn, Baker, Dracup, & Pitt, 1994).

Sleep disturbances have been reported as one of the most burdensome symptoms for people with HF (Zambroski, Moser, Bhat, & Ziegler, 2005). Up to 70% of the people with HF complained of sleep disturbances (Chen & Clark, 2007). Sleep disturbances, particularly sleep-related breath-ing disorders, can interrupt the HF compensatory mecha-nisms to accelerate the deterioration of cardiac function and, thus, increase the mortality of HF (Ancoli-Israel et al., 2003; Leung & Bradley, 2001) and reduce HRQOL (Brostrom, Stromberg, Dahlstrom, & Fridlund, 2004; Skobel et al., 2005; Villa et al., 2003). Understanding sleep disturbances could lead to better care for people with HF and improve HRQOL.

One challenge in examining sleep disturbances in people with HF is that many of the symptoms of sleep disturbances are seen as characteristics of HF, such as fatigue, resulting in difficulty in distinguishing symptoms of sleep distur-bances from symptoms of HF or HF treatment (Erickson, Westlake, Dracup, Woo, & Hage, 2003). Using reliable and validated sleep-specific instruments is a convenient and useful strategy for healthcare providers to identify sleep dis-turbance symptoms. The most common symptoms of sleep disturbances reported by patients with HF include having difficulty initiating sleep, waking up and having difficulty getting back to sleep, lacking sufficient refreshing sleep, having inability to sleep flat, having restless sleep, and awakening early (Erickson et al., 2003; Lainscak & Keber, 2003). Sleep disturbances, however, can also cause related effects, such as fatigue, irritability, and loss of concen-tration and further worsen patients’ sleep states (Brostrom, Stromberg, Dahlstrom, & Fridlund, 2001).

Hsing-Mei Chen, PhD, MSN, RN, is Assistant Professor, Chang Gang Institute of Technology Chia-Yi Campus, School of Nursing, Chia-Yi County, Taiwan.

Angela P. Clark, PhD, RN, CNS, FAAN, FAHA, is Associate Professor, The University of Texas at Austin, School of Nursing. Liang-Miin Tsai, MD, is Professor of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Medical Center, Taiwan.

Yann-Fen C. Chao, DNSc, RN, is Professor and Dean, Taipei Medical University School of Nursing, Taiwan.

The contributors of sleep disturbances among people with HF appear to be multifactorial and complex. There is growing recognition that sleep-related breathing disorders, including Cheyne-Stokes respiration with central sleep apnea (CSR-CSA) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), are common in people with HF, with a range of 10% to 60% (Chen & Clark, 2007). They have been shown consistently to cause sleep disruption due to repetitive arousals from sleep (Leung & Bradley, 2001). It is evident that CSR-CSA is more likely to occur in patients with HF with left ventricular ejection fractions less than 45%, whereas OSA may be an independent risk factor to the development of HF and a consequence of HF (Lanfranchi & Somers, 2003; Ventura, Potluri, & Mehra, 2003). Sleep-related breathing disorders, however, have to be recognized by using diagnostic laboratory tests, which may not be available for many patients and locations.

Only a few researchers have examined sleep disturbances from the patients’ perspective (Asplund, 2005; Brostrom et al., 2004; Erickson et al., 2003; Redeker & Hilkert, 2005). The limited research studies have suggested various factors related to self-reported sleep disturbances in people with HF. They included demographics such as age, gender, and marital status; HF characteristics, such as symptoms, severity, and treatment-related side effects; health-related characteristics, such as comorbidity, health perception, and functional performance; daily life activity and psychosocial stresses; and HRQOL. However, the associations between those factors and self-reported sleep disturbance have not been shown consistently across studies. Continued research is needed to identify patients who are at risk of sleep disturbance.

Information about predictors of self-reported sleep disturbance in HF is limited. Only one study has been done in this area (Erickson et al., 2003). The study found that demographic, clinical, or HF severity variables were not predictors of sleep disturbance symptoms in 84 people living with HF (Erickson et al., 2003). Similarly, Mystakidou et al. (2007) found that demographics and clinical variables did not predict sleep disturbance in 102 patients with cancer. However, they did find that poor HRQOL predicted sleep disturbances. Mystakidou et al. suggested that healthcare providers should not overlook the effect of HRQOL on sleep disturbance. In another study of patients with HF, Redeker and Hilkert (2005) argued that people with HF who experience poorer HRQOL may compensate by spending more time in bed and having longer sleep latency (Redeker & Hilkert, 2005). The need to understand the causal relationship between HRQOL and sleep dis-turbances, thus, is imperative.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate predictors of self-reported sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with HF. The study hypothesized that demographics, HF characteristics, health-related characteristics, and HRQOL were correlated with self-reported sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with HF. In particular, HRQOL could have a significant effect on sleep disturbances, after controlling for demographics, HF characteristics, and health-related characteristics. The study was conducted

with Taiwanese people with HF because there was no information about sleep disturbances in this population to date. The importance of sleep disturbances may be under-studied because many Taiwanese people tend to attribute sleep disturbances to physical diseases caused by the imbalance of yin and yang and disharmony with nature (Lee, 1995). They may consider not sleeping well reason-able and natural and, thus, engage in few actions to seek help for their sleep condition (Wang, 2005). Understanding the extent of patients’ sleep disturbances and the predictors of sleep disturbances, however, is needed to design effective interventions for the management of this aspect of HF.

Methods

Design

The study used a cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational design. Participants were interviewed individually by the principal investigator at clinical sites or in their homes. Setting and Sample

A purposive sample of 125 participants was recruited from the outpatient departments of a large medical center and an affiliated hospital located in southern Taiwan. This study was reviewed by institutional review boards before data collection. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) a diagnosis of HF with any New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification I, II, III, or IV as determined by physicians; (b) age of 18 years or older; (c) community dwelling; (d) able to communicate either by speaking Mandarin or Taiwanese or writing Mandarin (the official Chinese language); and (e) willing to participate in this study. A minimum sample size of 113 participants was calculated based on Cohen’s (1988) statistical power analysis method, with a level of power of .8 at a significant alpha level of .05. The effect size (.26) was estimated using the smallest Spearman rank correlation coefficient among the associations between sleep variables and major inde-pendent variables from a prior pilot study (n = 13). Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire The demographic

question-naire included demographics, HF characteristics, and health-related characteristics. Demographic data consisted of age, gender, education, marital status, financial status, and employment status. The HF characteristics included type of HF, time since the HF diagnosis, and NYHA class. Health-related characteristics included perceived health, comorbidity, and body mass index (calculated using height and weight).

Charlson Comorbidity Index Comorbidity was measured

using the 19-item Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which is an approach of quantifying preexisting comorbid-ities using medical records (Charlson, Pompei, Ales, & MacKenzie, 1987). The CCI is calculated using assigned weights for each condition (0, 1, 3, or 6) to reflect both the number and the seriousness of the comorbidities. A self-reported version of the CCI was developed by Katz, Chang, Sangha, Fossel, and Bates (1996). The 16-item self-reported CCI has been validated using a sample of

170 inpatients older than 55 years. Respondents were asked to evaluate their comorbid conditions on a two-point scale (yesYno). Intraclass coefficient and Spearman coefficient for testYretest reliability at an interval of 7 to 8 months for the self-reported CCI were .91 and .73, respectively (n = 26). Spearman correlation between the self-report method and the medical-record-based CCI (Charlson et al., 1987) was .63. The self-reported CCI was translated from English into Mandarin Chinese by the principal investi-gator for this study.

Perceived Health Scale Perceived health is individuals’

overall evaluation of their existing health status. Per-ceived health was measured using the two-item PerPer-ceived Health Scale that was adopted from the original four-item Self-rated Health Subscale (Lawton, Moss, Fulcomer, & Kleban, 1982). Respondents were asked to evaluate their overall health and compare their health to 1 year ago on a 4- and 3-point scale. The total score ranges from 2 to 7, with a higher score indicating better health per-ception. Cronbach’s alpha for the Perceived Health Scale was .55.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index The Pittsburgh Sleep

Qual-ity Index (PSQI) was used to measure sleep disturbance (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). It is composed of 18 self-report items regarding sleep quality and sleep disturbances, 1 question asking participants whether they have a bed partner or roommate, and 5 questions rated by the participants’ bed partner or room-mate. The 18 items are grouped into seven components: subjective sleep quality (1 item), sleep latency (2 items), sleep duration (1 item), habitual sleep efficiency (3 items), sleep disturbances (9 items), use of sleeping medication (1 item), and daytime dysfunction (2 items) over a 1-month period. Each component of the PSQI is weighted equally, with a possible scale range of 0Y3. The seven component scores are then summed to produce a global score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates a poor sleep quality. A global PSQI score greater than 5 yielded a sensitivity of 89.6% and a specificity of 86.5% as a cutoff point for identifying poor sleepers (Buysse et al., 1989). The index takes respondents 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

The PSQI was translated into Mandarin Chinese and tested for its psychometric properties by Tsai et al. (2005). Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency reliability was .83 for 208 adults and .72 for 51 primary insomniacs. Pearson correlation coefficient for the testYretest reliability was .85 for all participants and .77 for 51 primary insomniacs at an interval of 2 to 3 weeks. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for domains of PSQI was sleep latency = .78, sleep disturbances = .51, daytime dysfunction = .79, and global PSQI = .70.

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire The Kansas

City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) was used to measure HRQOL (Green, Porter, Bresnahan, & Spertus, 2000). The KCCQ is a 23-item self-report questionnaire designed to quantify several HF-specific domains of HRQOL: physical limitations (6 items); symptoms, includ-ing frequency (4 items) and severity (3 items); symptom stability (1 item); self-efficacy (2 items); social functioning

(4 items); and quality of life (QOL, 3 items; Green et al., 2000). An overall summary score is computed by totaling the scores of the physical limitation, symptom, QOL, and social functioning domains (Green et al., 2000). Patients are asked to answer questions on how HF has affected their lives over the previous 2 weeks. Items are scored using an ordinal response scale ranging from 1 to 7. Score for each domain was transformed to a 0Y100 scale, with a higher score indicating better health status. The average comple-tion time for the KCCQ is approximately 4 to 6 minutes (Green et al., 2000).

The KCCQ was translated into Mandarin Chinese for this study. John Spertus (developer of the KCCQ) served as one of the consultants in the translation project. Knowl-edge about cultural equivalence between the original and translated versions was used to guide the translation (Herdman, Fox-Rushby, & Badia, 1998). Cronbach’s alpha for each domain was from .90 (overall summary score) to .50 (self-efficacy).

Data Analysis

Data collected for this study were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (Version 14.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data analysis approaches included (a) descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage; (b) bivariate correlations for testing relationships between variables; and (c) hierarchical multiple regression analyses with forward method for identifying significant predictors of nocturnal sleep quality. The level of significance was set at .05 for all statistical analyses.

Before employing the hierarchical multiple regression analysis, the data were examined to ensure that they met the assumptions of multiple regression analysis. The assumptions included the following: (a) The normality of the Studentized residual (takes into account the differences in variability from point to point) was examined using analyses of a stem-and-leaf plot and a histogram in addition to a QYQ plot; (b) independence was assessed using the DurbinYWatson test with the Statistical Package for the Social Science software (normal range = 1.5 to 2.5; Norusis, 2004); (c) linearity assumption was evaluated by plotting Studentized residuals against the global PSQI score; and (d) homoscedasticity was examined by plotting the Studentized residuals against the predicted values. Multicollinearity was assessed for all variables that were entered into the regression model by using correlation coefficients (less than .80), tolerances (equal or greater than .2), and variance inflation factors (less than 5; Hutcheson & Sofroniou, 1999).

Results

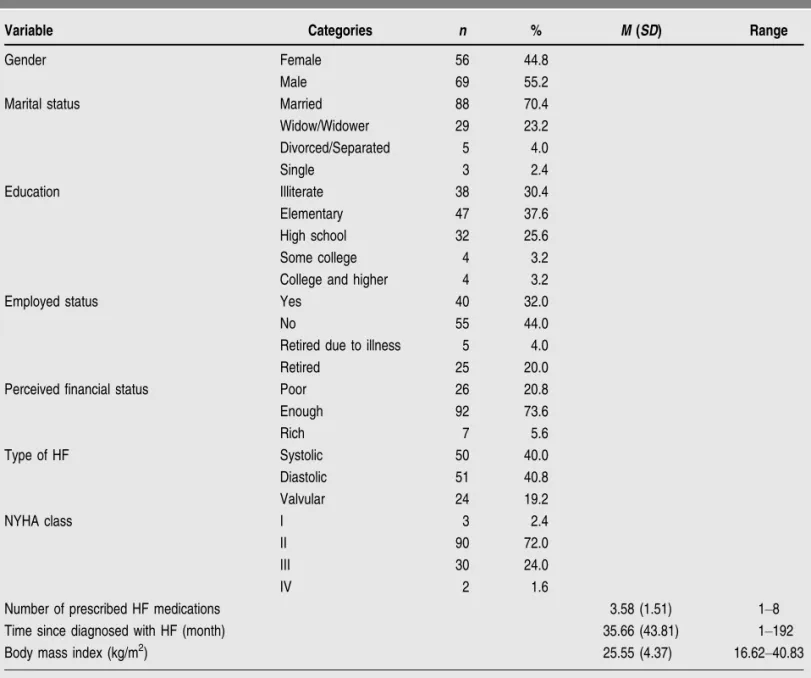

A total of 125 participants were enrolled in the study. Participants’ demographic, HF, and health-related charac-teristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 67.79 years (SD = 12.19 years). Most of the participants were men (55.2%), married (70.4%), literate (69.6%), and unemployed or retired (68%) and reported adequate financial status (79.2%). Forty percent of the participants had systolic HF, 40.8% had diastolic

dysfunction, and 19.2% had valvular HF. In Taiwan, these three types are used to describe the etiology of HF (Patel & Konstam, 2001). The majority (72.0%) were in NYHA Class II, indicating a low level of HF severity. The mean number of prescribed HF medications used was 3.58 (SD = 1.51), the mean duration since their HF diagnoses was 35.66 months (SD = 43.81 months), and the mean BMI was 25.55 kg/m2 (SD = 4.37 kg/m2). The average CCI severity score was 2.39 (SD = 1.88), and the mean comorbidity number was 1.86 (SD = 1.25). The perceived health score ranged from 2 to 7, with a mean of 3.26 (SD = 1.07).

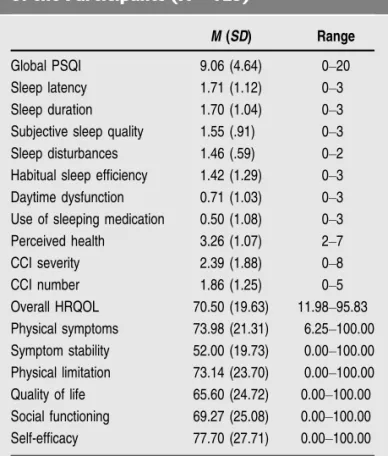

Self-reported Sleep Disturbance The global PSQI scores

of the 125 participants ranged from 0 to 20, with a mean score of 9.06, a median of 8.00, and a mode of 4.00. With a cutoff point of 5 (Buysse et al., 1989), 93 (74.4%) partici-pants were identified as poor sleepers (PSQI greater

than 5). Approximately half of the participants, however, rated their sleep as fairly good, and only 42.8% rated their sleep as fairly bad or very bad. The mean daily sleep dura-tion was 5.62 hours (SD = 1.72 hours). Thirty-six percent of the participants reported that they had a total night’s sleep of 5 to 6 hours, and 25.6% slept less than 5 hours a night. The mean sleep latency was 46.2 minutes (SD = 57.63 minutes). Approximately 40.8% of the participants took less than 15 minutes to fall asleep, whereas 19.2% took more than 1 hour to fall asleep. The mean habitual sleep efficiency was 73% (SD = 22%). Forty-seven (37.6%) had habitual sleep efficiencies of 85%, and 32.8% had sleep efficiencies of less than 65%. A large proportion (80.8%) of the participants did not use sleeping medica-tions, whereas 14.4% took sleeping pills 3 or more days a week during the last month. Similarly, most participants (62.4%) reported that they did not suffer from daytime dys-function, whereas 9.6% had severe problems performing q

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 125)

Variable Categories n % M (SD) Range

Gender Female 56 44.8

Male 69 55.2

Marital status Married 88 70.4

Widow/Widower 29 23.2 Divorced/Separated 5 4.0 Single 3 2.4 Education Illiterate 38 30.4 Elementary 47 37.6 High school 32 25.6 Some college 4 3.2

College and higher 4 3.2

Employed status Yes 40 32.0

No 55 44.0

Retired due to illness 5 4.0

Retired 25 20.0

Perceived financial status Poor 26 20.8

Enough 92 73.6 Rich 7 5.6 Type of HF Systolic 50 40.0 Diastolic 51 40.8 Valvular 24 19.2 NYHA class I 3 2.4 II 90 72.0 III 30 24.0 IV 2 1.6

Number of prescribed HF medications 3.58 (1.51) 1Y8

Time since diagnosed with HF (month) 35.66 (43.81) 1Y192

Body mass index (kg/m2) 25.55 (4.37) 16.62Y40.83

their daily functions. Scores for PSQI components are shown in Table 2 and sleep disturbances in Table 3.

Health-Related Quality of Life Scores for HRQOL

domains are shown in Table 2. The self-efficacy domain had the highest score among domains of HRQOL (mean = 77.70, SD = 27.71), and QOL was the lowest (mean = 65.60, SD = 24.72).

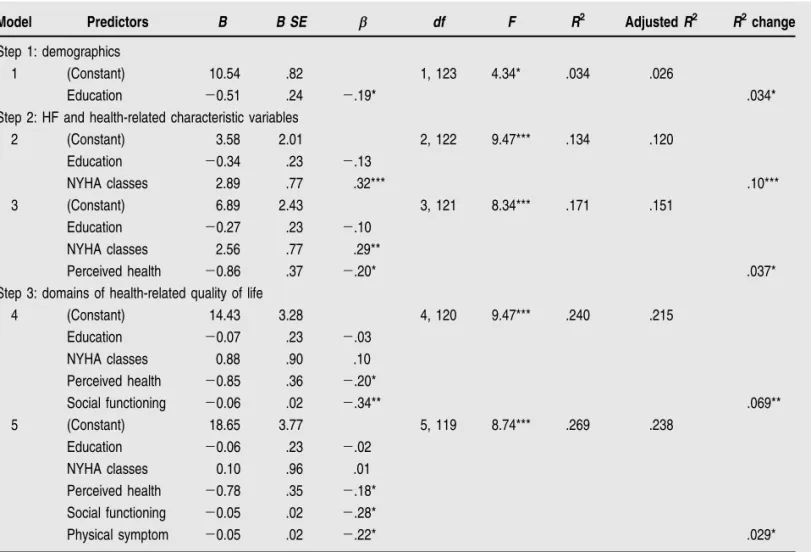

Predictors of Self-reported Sleep Disturbances Bivariate

correlation analyses showed that 10 variables were weakly to moderately but significantly associated with the global PSQI score. They were demographic variables, including gender (r = j.18, p G .05) and education (r = j.18, p G .05); HF characteristic, including NYHA class (r = .35, pG .001); health-related characteristics, including CCI (r = .20, pG .05) and perceived health (r = j.27, p G .001); and 5 domains of HRQOL, including physical limitation (r = j.36, p G .001), physical symptom (r = j.41, p G .001), symptom stability (r = j.21, pG .01), QOL (r = j.28, p G .001), and social functioning (r = j.44, pG .001).

To identify predictors of self-reported sleep distur-bances, the 10 variables then were entered into the regres-sion model based on three hierarchical steps: demographic variables, HF and health-related characteristic variables, and HRQOL variables. Gender and education were avail-able to enter in the first step as covariates. Education, which was the only significant predictor in this step,

ac-counted for 3.4% of the variance (p G .05). The NYHA class, CCI, and perceived health were available to enter inthe second step. Two significant predictors were identified from these three variables. The NYHA class accounted for an additional 10% of the variance in sleep disturbances (p G .001), and perceived health increased the variance by 3.7% (pG .01), from 13.4% to 17.1%. When five KCCQ domainsVphysical limitation, physical symptom, symp-tom stability, QOL, and social limitationVwere available to enter into the third step, only social functioning and physical symptoms were significant predictors of sleep dis-turbances among the five predictor variables. Social func-tioning accounted for an additional 6.9% of the variance (pG .01), and physical symptoms increased the variance by 2.9%, from 24.0% to 26.9%. The summary for the sig-nificant predictor variables on self-reported sleep distur-bances is shown in Table 4.

Overall, the total variance explained by the final model was 26.9%. After controlling for education, NYHA class, and perceived health, the analysis showed that two variablesVsocial functioning and physical symptomV accounted for 9.8% of the variance in sleep disturbances. Participants who experienced poorer social functioning and fewer physical symptoms reported greater sleep disturbances.

Discussion

The findings suggest that sleep disturbances should be taken into account when managing patients’ HF. This study yielded a mean Global Sleep Quality score of 9.06 from the PSQI questionnaire, indicating that sleep distur-bances were a significant problem for patients with HF in the study. Although the PSQI is intended primarily to measure sleep disturbances and identify good or poor sleepers rather than to provide a clinical diagnosis, the q

TABLE 2. Global PSQI and Component Scores of the Participants (N = 125)

M (SD) Range

Global PSQI 9.06 (4.64) 0Y20

Sleep latency 1.71 (1.12) 0Y3

Sleep duration 1.70 (1.04) 0Y3

Subjective sleep quality 1.55 (.91) 0Y3

Sleep disturbances 1.46 (.59) 0Y2

Habitual sleep efficiency 1.42 (1.29) 0Y3

Daytime dysfunction 0.71 (1.03) 0Y3

Use of sleeping medication 0.50 (1.08) 0Y3

Perceived health 3.26 (1.07) 2Y7

CCI severity 2.39 (1.88) 0Y8

CCI number 1.86 (1.25) 0Y5

Overall HRQOL 70.50 (19.63) 11.98Y95.83

Physical symptoms 73.98 (21.31) 6.25Y100.00

Symptom stability 52.00 (19.73) 0.00Y100.00

Physical limitation 73.14 (23.70) 0.00Y100.00

Quality of life 65.60 (24.72) 0.00Y100.00

Social functioning 69.27 (25.08) 0.00Y100.00

Self-efficacy 77.70 (27.71) 0.00Y100.00

Note. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; HQROL = health-related quality of life.

q

TABLE 3. Self-reported Conditions Causing Sleep Disturbances (N = 125)

Score M (SD) 0Y1, n (%) 2Y3, n (%)

Condition

Have to get up to use the bathroom

2.51 (1.29) 21 (16.8) 104 (83.2)

Cannot get to sleep within 30 minutes

1.90 (1.29) 47 (37.6) 78 (62.4)

Wake up at midnight or early morning

1.63 (1.35) 55 (44.0) 70 (56.0)

Have a bad dream 0.92 (1.25) 91 (72.8) 34 (27.2)

Have pain 0.66 (1.14) 97 (77.6) 28 (22.4)

Cough or snore loudly 0.63 (1.10) 99 (79.2) 26 (20.8)

Cannot breathe comfortably

0.52 (1.01) 102 (81.6) 23 (18.4)

Feel too hot 0.25 (0.72) 116 (92.8) 9 (7.2)

Feel too cold 0.21 (0.73) 118 (94.4) 7 (5.6)

Note. 0 = not during the past month; 1 = less than once a week; 2 = once or twice a week; 3 = three or more times a week.

findings suggest a higher 1-month prevalence of sleep disturbance (74%). For participants with greater scores on the PSQI, however, the findings can serve as references for confirming sleep disturbances, which need to be addressed by clinicians. Using more objective measure-ments such as diagnostic criteria and polysomnography will be useful for patients with potential sleep-related breathing disorders, such as CSR-CSA and OSA.

Nocturia was the most frequent cause of sleep dis-turbance, affecting 104 (83.2%) of the participants in the sample. Nocturia in HF is a consequence of an increase in the atrial natriuretic peptide hormone (Asplund, 2004). The effects of nocturnal polyuria, which include dry eyes and dry mouth, might explain partially the finding that 11.2% of the participants complained of dry mouth during sleep and had to get up to drink liquids. The previous studies have shown that nocturia was correlated with less sleep among community-dwelling adults aged 40 years and older (Yu et al., 2006) and poorer sleep quality and higher mortality in older adults (Asplund, 2005). However, the lack of adequate information about the effect of nocturia

on sleep suggests that nocturia is an area that has been ignored in HF clinical practice.

Education played an important role in sleep distur-bances in this sample. Participants with higher educational levels reported greater sleep efficiency and better overall sleep quality. This finding was consistent with the Coro-nary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, which showed that more education correlated with greater sleep efficiency (Lauderdale et al., 2006). Similarly, in the Office of National Statistics Omnibus Survey in the United Kingdom, Adams (2006) found that women with lower levels of education reported a greater quantity of sleep (greater than 8.5 hours per night) compared with those with higher levels of education. In the current study, approximately 30% of the participants were illiterate. It is not clear whether Taiwanese people with lower educa-tion have greater difficulty in receiving medical informaeduca-tion printed in the Mandarin Chinese language. As a result, they may have poorer ability to adjust to their illness and employ better critical thinking in making decisions about their treatments. More research is needed to further q

TABLE 4. Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Predictor Variables on Sleep Disturbances (N = 125)

Model Predictors B B SE " df F R2 Adjusted R2 R2change

Step 1: demographics

1 (Constant) 10.54 .82 1, 123 4.34* .034 .026

Education j0.51 .24 j.19* .034*

Step 2: HF and health-related characteristic variables

2 (Constant) 3.58 2.01 2, 122 9.47*** .134 .120 Education j0.34 .23 j.13 NYHA classes 2.89 .77 .32*** .10*** 3 (Constant) 6.89 2.43 3, 121 8.34*** .171 .151 Education j0.27 .23 j.10 NYHA classes 2.56 .77 .29** Perceived health j0.86 .37 j.20* .037*

Step 3: domains of health-related quality of life

4 (Constant) 14.43 3.28 4, 120 9.47*** .240 .215 Education j0.07 .23 j.03 NYHA classes 0.88 .90 .10 Perceived health j0.85 .36 j.20* Social functioning j0.06 .02 j.34** .069** 5 (Constant) 18.65 3.77 5, 119 8.74*** .269 .238 Education j0.06 .23 j.02 NYHA classes 0.10 .96 .01 Perceived health j0.78 .35 j.18* Social functioning j0.05 .02 j.28* Physical symptom j0.05 .02 j.22* .029*

Note. Analyzed by the forward method. F for final equation = 8.74, with df = 5, 119, pG .001. HF = heart failure; NYHA class = New York Heart Association functional classification.

*pG .05. **pG .01 level. ***pG .001 (two-tailed).

understand the effect of health literacy on sleep condition in people with HF.

Although approximately 72% of the participants were in NYHA Class II, this study found that participants who had higher NYHA classifications experienced more sleep disturbances. The finding was similar to previous study findings (Principe-Rodriguez, Strohl, Hadziefendic, & Pina, 2005; Redeker & Hilkert, 2005) but incon-sistent with that by Erickson et al. (2003). However, NYHA classification was not a significant predictor of sleep disturbance when HRQOL social func-tioning and physical symptom were added to the regression model, partic-ularly social functioning. This indicated

that HRQOL including social functioning and physical symptoms may mediate the effect of NYHA class on sleep disturbances. Further research is needed to clarify the causal relationships among sleep disturbances, NYHA classes, and HRQOL.

The participants appeared to avoid using sleeping medication despite its benefits. Almost half of the par-ticipants reported poor subjective sleep quality, yet only 16.8% used sleeping medication for their sleep problems once or more per week over the month before the interview for this study. The use of sleeping medication was lower than that in the study of Erickson et al. (2003) of patients with HF (32%) and the study of Lin, Su, and Chang (2003) of institutionalized elderly people (38.5%). During the interviews for this study, several participants explained that they did not take sleeping medication frequently because of their concerns about sleeping medication dependence and about interactions between sleeping medication and HF medications. In addition, a small number of the partic-ipants explained that many of their friends and physicians attributed their sleep problems to mental problems, and as a result, the participants felt too embarrassed to continue seeking medical help. That finding suggests that healthcare providers should refrain from attributing sleep disorders to psychogenic illnesses when they discuss the causes of sleep disorders with Taiwanese people (Lee, 1995). By avoiding the use of psychological terms and phrases such as neuro-sis, anxiety, and worry too much, healthcare providers might be more effective in helping patients. The underlying causes of the sleep disorders, including both physical and psychological mechanisms, should be identified to help obtain accurate diagnoses and plan effective interventions. Although the severity of HF in the participants in this study was low, perceived health was found to be a predictor of sleep disturbance. Participants who perceived poorer health experienced more sleep disturbances. The findings were similar to those of Katz and McHorney (2002) that perceived health was correlated with insomnia in people with chronic illness. In the sleep study across three Asian countries, Nomura, Yamaoka, Nakao, and Yano (2005) also found that insomnia was associated with health dissatisfaction in general Taiwanese people. It is worth noting that many participants in the current study

indicated that they perceived that their health predominantly hindered them from doing the things they wanted. As a result, they adopted sedentary lifestyles to prevent exacerbation of their HF condition. It is possible that improve-ments in perceived health may lead to improvements of sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with HF.

The finding that HRQOL influ-enced sleep disturbance was similar with that in a study of patients with cancer (Mystakidou et al., 2007). How-ever, physical symptom in this current study was a predictor of sleep distur-bance, which was inconsistent with the finding of Erickson et al. (2003), which showed that HF symptoms did not predict significant sleep disturbances. In this study, par-ticipants who suffered from the symptoms of swelling, fatigue, and shortness of breath reported more sleep disturbances. Results from the current study may support the view that participants with greater HF symptoms are more likely to experience sleep disturbances. Further clarification is needed of whether sleep disturbances are caused by HF itself or by sleep-related breathing disorders such as OSA and central sleep apnea.

Social functioning explained 6.9% of the variance in sleep disturbances. Participants who had greater limitations in pursuing hobbies, recreational activities, household chores, working, visiting families or friends, and maintaining intimate relationships with loved ones experienced higher sleep difficulties. Skobel et al. (2005) found that social functioning was correlated moderately with apnea or hypo-pnea index in patients with HF and sleep-related breathing disorders. Dissatisfaction with social life was a predictor of insomnia in samples aged 15 years and older taken from three general populations, namely, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Italy (Ohayon, Zulley, Guilleminault, Smirne, & Priest, 2001). Satisfaction with social life was also a protective factor against insomnia for persons of any age. Life events such as retirement, death of a spouse, and physical and mental illnesses could have a great influence on the sleepYwake pattern. Encouraging patients to continue to engage in social activities is an important intervention for helping them preserve better sleep health. Several par-ticipants in the current study, however, stated that the reason they did not engage in hobbies or recreational activities was that they were exercise intolerant. Therefore, interventions to enhance cardiopulmonary fitness have to be considered when patients are being encouraged to en-gage in social activities.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Because the data were collected from one medical center and an affiliated hospital located in southern Taiwan, the study findings may not reflect the situations of the patients who were living in other areas of Taiwan. The lack of objective sleep measure-ment data using laboratory devices and diagnostic criteria limited the ability to identify and diagnose sleep-related

Encouraging patients to continue to engage in

social activities is an important intervention for

helping them preserve better sleep health.

breathing disorders. Future research should include partic-ipants with more severe HF and typical HF symptoms to help understand the effects of HF on sleep disorders. Likewise, longitudinal studies are needed to identify the development and trajectory of sleep disorders in people with HF.

Conclusions

Several factors were associated with sleep disturbances, sug-gesting that sleep is a complex concept. Healthcare pro-viders must understand the often multifactorial nature of sleep disturbances to achieve more effective management. The importance of ongoing screening for sleep disturbances in people with HF is highlighted based on the study find-ings about the prevalence of sleep disturbances among the participants in this study. Early detection of sleep distur-bances may help healthcare providers improve outcomes in people with HF. Likewise, assessing patients’ HF severity and HRQOL and impact on sleep is important as a part of HF care and teaching. Effective interventions including pharmacological (e.g., sleeping medication) and nonphar-macological treatments (e.g., relaxation strategies) for sleep disturbances in patients with HF should be designed in accordance with each patient’s lifestyle. Replication stud-ies, however, are needed to support the findings of this current study. q

Accepted for publication July 7, 2008.

Corresponding author: Hsing-Mei Chen, PhD, MSN, RN, Room A502, No. 2, Chia-pu Road, West Sec. Pu-tz, Chiayi, 61363, Taiwan (e-mail: hsingmei@ntu.edu.tw).

References

Adams, J. (2006). Socioeconomic position and sleep quantity in UK adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(3), 267Y269.

Ancoli-Israel, S., DuHamel, E. R., Stepnowsky, C., Engler, R., Cohen-Zion, M., & Marler, M. (2003). The relationship between congestive heart failure, sleep apnea, and mortality in older men. Chest, 124(4), 1400Y1405.

Asplund, R. (2004). Nocturia, nocturnal polyuria, and sleep quality in the elderly. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(5), 517Y525.

Asplund, R. (2005). Nocturia in relation to sleep, health, and medical treatment in the elderly. BJU International, 96(Suppl. 1), 15Y21.

Brostrom, A., Stromberg, A., Dahlstrom, U., & Fridlund, B. (2001). Patients with congestive heart failure and their con-ceptions of their sleep situation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(4), 520Y529.

Brostrom, A., Stromberg, A., Dahlstrom, U., & Fridlund, B. (2004). Sleep difficulties, daytime sleepiness, and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(4), 234Y242.

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., 3rd, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychia-try Research, 28(2), 193Y213.

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L., & MacKenzie, C. R. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in

longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(5), 373Y383.

Chen, H. -M., & Clark, A. P. (2007). Sleep disturbances in people living with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22(3), 177Y185.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Erickson, V. S., Westlake, C. A., Dracup, K. A., Woo, M. A., & Hage, A. (2003). Sleep disturbance symptoms in patients with heart failure. AACN Clinical Issues, 14(4), 477Y487.

Green, C. P., Porter, C. B., Bresnahan, D. R., & Spertus, J. A. (2000). Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiol-ogy, 35(5), 1245Y1255.

Hadorn, D., Baker, D., Dracup, K., & Pitt, B. (1994). Making judgements about treatment effectiveness based on health outcomes: Theoretical and practical issues. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 20(10), 547Y554.

Herdman, M., Fox-Rushby, J., & Badia, X. (1998). A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: The universalist approach. Quality of Life Research, 7(4), 323Y335.

Hutcheson, G. D., & Sofroniou, N. (1999). Introductory statistics using generalized linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Katz, D. A., & McHorney, C. A. (2002). The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. Journal of Family Practice, 51(3), 229Y235. Katz, J. N., Chang, L. C., Sangha, O., Fossel, A. H., & Bates, D. W.

(1996). Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Medical Care, 34(1), 73Y84. Lainscak, M., & Keber, I. (2003). Patient’s view of heart failure:

From the understanding to the quality of life. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2(4), 275Y281.

Lanfranchi, P. A., & Somers, V. K. (2003). Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure: Characteristics and implications. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 136(2Y3), 153Y165. Lauderdale, D. S., Knutson, K. L., Yan, L. L., Rathouz, P. J.,

Hulley, S. B., Sidney, S., et al. (2006). Objectively measured sleep characteristics among earlyYmiddle-aged adults: The CARDIA study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 164(1), 5Y16.

Lawton, M. P., Moss, M., Fulcomer, M., & Kleban, M. H. (1982). A research and service oriented multilevel assessment instrument. Journal of Gerontology, 37(1), 91Y99.

Lee, Y. J. (1995). Sleep disorders in Chinese culture: Experiences from a study of insomnia in Taiwan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 49(2), 103Y106.

Leung, R. S. T., & Bradley, T. D. (2001). Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 164(12), 2147Y2165.

Lin, C. L., Su, T. P., & Chang, C. (2003). Quality of sleep and its associated factors in the institutionalized elderly. Formosan Journal of Medicine, 7, 174Y184.

Mystakidou, K., Parpa, E., Tsilika, E., Pathiaki, M., Gennatas, K., Smyrniotis, V., et al. (2007). The relationship of subjective sleep quality, pain, and quality of life in advanced cancer patients. Sleep, 30(6), 737Y742.

Nomura, K., Yamaoka, K., Nakao, M., & Yano, E. (2005). Impact of insomnia on individual health dissatisfaction in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Sleep, 28(10), 1328Y1332. Norusis, M. (2004). SPSS 12.0 guide to data analysis. Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ohayon, M. M., Zulley, J., Guilleminault, C., Smirne, S., & Priest, R. G. (2001). How age and daytime activities are related to insomnia in the general population: Consequences for older

people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49(4), 360Y366.

Patel, A. R., & Konstam, M. A. (2001). Assessment of the patient with heart failure. In M. H. Crawford, & J. P. DiMarco (Eds.), Cardiology (pp. 5.2.1Y10). London: Mosby.

Principe-Rodriguez, K., Strohl, K. P., Hadziefendic, S., & Pina, I. L. (2005). Sleep symptoms and clinical markers of illness in patients with heart failure. Sleep & Breathing, 9(3), 127Y133. Redeker, N. S., & Hilkert, R. (2005). Sleep and quality of life

in stable heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 11(9), 700Y704.

Skobel, E., Norra, C., Sinha, A., Breuer, C., Hanrath, P., & Stellbrink, C. (2005). Impact of sleep-related breathing disorders on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 7(4), 505Y511. Tsai, P. -S., Wang, S. -Y., Wang, M. -Y., Su, C. -T., Yang, T. -T.,

Huang, C. -J., et al. (2005). Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Quality of Life Research, 14(8), 1943Y1952.

Ventura, H. O., Potluri, S., & Mehra, M. R. (2003). The conundrum of sleep breathing disorders in heart failure. Chest, 123(5), 1332Y1334.

Villa, M., Lage, E., Quintana, E., Cabezon, S., Moran, J. E., Martinez, A., et al. (2003). Prevalence of sleep breathing disorders in outpatients on a heart transplant waiting list. Transplantation Proceedings, 35(5), 1944Y1945.

Wang, F. -T. (2005). Quality of life, self-care behavior and social support in patients with heart failure. Unpublished thesis, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei.

Young, J. B. (2004). The global epidemiology of heart failure. Medical Clinics of North America, 88(5), 1135Y1143. Yu, H. -J., Chen, F. -Y., Huang, P. -C., Chen, T. H. -H., Chie, W. -C.,

& Liu, C. -Y. (2006). Impact of nocturia on symptom-specific quality of life among community-dwelling adults aged 40 years and older. Urology, 67(4), 713Y718.

Zambroski, C. H., Moser, D. K., Bhat, G., & Ziegler, C. (2005). Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 4(3), 198Y206.