©2006 Elsevier & Formosan Medical Association

. . . .

Department of Neurology, National Taiwan University Hospital, College of Medicine, 1Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, and 2Department of Nursing, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: July 12, 2005 Revised: September 6, 2005 Accepted: January 10, 2006

*Correspondence to: Dr Ming-Jang Chiu, Department of Neurology, National Taiwan University Hospital, 7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

E-mail: mjchiu@ntumc.org

There is a growing awareness of the importance of behavioral and psychologic symptoms of de-mentia (BPSD) among patients with dede-mentia. There are several reasons for this. First, BPSD are major sources of a caregiver’s burden1,2and also the most important factor to consider when insti-tutionalizing dementia patients.3Second, despite recent advances in “cognitive enhancing drugs”

such as cholinesterase inhibitors, the capability of modern medicine to improve cognitive functions or delay the mental deterioration process in pa-tients with dementia remains modest.4Third, the development of new generation atypical antipsy-chotics and antidepressants brings substantial re-lief to the frequently encountered BPSD with fewer motor, cognitive and autonomic toxicities to the

Behavioral and Psychologic Symptoms in

Different Types of Dementia

Ming-Jang Chiu,* Ta-Fu Chen, Ping-Keung Yip, Mau-Sun Hua,1Li-Yu Tang2

Background/Purpose: Behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are major sources of a caregiver’s burden and also the most important factor when considering the need for institutionalization of dementia patients. BPSD occur in about 90% of patients with dementia. Studies comparing the BPSD in the major types of dementia using unitary behavioral rating scales are limited. We studied BPSD in patients with four major types of dementias from a memory clinic.

Methods: We recruited patients with dementia from our memory clinic from January 2003 to February 2004. The Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) was used to measure BPSD sever-ity. Clinical Dementia Rating and Mini Mental State Examination were used to determine dementia seversever-ity. Results: A total of 137 patients with four major types of dementia were recruited from 155 patients with dementia who attended the clinic during the study period. The main dementia types identified were Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) in 54.8%, vascular dementia (VaD) in 20.6%, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in 8.4%, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) in 4.5%, and other dementias in 11.6%. BPSD were found in 92.0% of the patients but only 43.1% received psychotropic treatment. The relative risk of receiv-ing psychotropic treatment for BPSD subscales paralleled the extent of caregivers’ burden as assessed by the BEHAVE-AD global rating. Type-specific BPSD, e.g. hallucination was identified for DLB, activity disturbances for FTD, anxiety and phobias for AD and affective disturbance for VaD.

Conclusion: A strategy of targeting type-specific BPSD may be beneficial, such as environmental stimulus control for DLB patients who are prone to have hallucinations, design of a pacing path for patients with FTD who need support for symptoms of wandering and emotional support for patients with VaD who are susceptible to depression. [J Formos Med Assoc 2006;105(7):556–562]

Key Words: Alzheimer’s dementia, behavior, dementia of Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia, psychologic symptoms, vascular dementia

elderly. Study of the nature, prevalence, clinical typing, staging of severity and use of medications in patients with BPSD is required to improve our ability to treat and to care for patients with dif-ferent types of dementia. BPSD are seen in about 90% of patients with dementia.5Among the var-ious types of dementia, BPSD have been best studied in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A review of 24 studies of psychosis involving more than 2200 patients found that delusion was reported in 11–73% of all patients.6There are several rea-sons for such wide variation in the prevalence rates of delusion as well as other BPSD, but the most important is the lack of a consistent ap-proach in defining and measuring BPSD. For ex-ample, lower rates (22%) of delusions in AD patients may be due to a sampling of BPSD occur-ring only in the 4 weeks prior to the interview.7 The most prominent aspect of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a profound change in person-ality and social conduct compared with the pre-morbid state. Verbal outbursts and inappropriate activities were more common among FTD than among AD patients.8 The most frequent BPSD in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are visual hallucinations and delusions. Paranoid delu-sions have been reported to occur in up to 80% and hallucinations in up to 60% of patients with DLB.9,10 Vascular dementia (VaD) is associated with a high frequency of psychosis; delusions may occur in up to 50% of patients11and VaD is also more likely to cause depression (45%) than AD (17%).12However, previous studies have not compared BPSD among the major types of dem-entia using a unitary behavioral rating scale. This is very important since different behavioral rating scales might have different emphasis or weight-ing on various dimensions of BPSD. Furthermore, the appearance and distribution of BPSD and even the caregiver’s burden may be affected by many factors including different cultural back-grounds.13This study obtained clinical informa-tion from patients with various major types of dementia from a single outpatient clinical popu-lation, some of whom received psychotropic medications for their BPSD.

Methods

SubjectsPatients with dementia attending a university hos-pital memory clinic between January 2003 and February 2004 were recruited. Patients with dementia or suspected dementia in the hospital were referred to the clinic for diagnosis and treat-ment, and to facilitate caregiver support through consultation and education. Patients who visited the memory clinic received a thorough history tak-ing and comprehensive physical and neurologic examinations. Mental status examinations were also performed, which typically used a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)14 and/or a Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument.

Neuroimaging, biochemical, and hemato-logic studies were performed to rule out treatable causes of dementia. In patients with atypical findings, further detailed neuropsychologic stud-ies were performed to assess general and spe-cific cognitive functions as well as psychiatric symptoms.

Patients were grouped according to the fol-lowing diagnostic criteria: NINCDS-ADRDA cri-teria for AD;15NINDS-AIREN criteria for VaD;16 McKeith et al’s17consensus of diagnosis for DLB; and Neary et al’s18 criteria for FTD. The use of psychotropic medications was recorded. Those patients who failed to visit the memory clinic on a regular basis or had too few visits for adequate information gathering were excluded.

Assessment

After obtaining informed consent, the caregivers were interviewed with the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD)19 to identify and to describe the BPSD of the patient in the past 3 months. The BEHAVE-AD is a 26-item observer rating scale containing seven subscales, each rated 0–3 as follows:

(1) paranoid and delusional ideation; (2) hallucinations;

(3) activity disturbances; (4) aggressiveness;

(6) affective disturbance; and (7) anxiety and phobias.

The 26thitem is a global rating which can be used as an index of the caregiver’s burden due to the BPSD, in which 0 indicates “not at all troubling to the caregiver or dangerous to the patient”; and 3 indicates “severely troubling or intolerable to the caregiver or dangerous to the patient”. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)20was used to evaluate and to stage patients with dementia. MMSE was also administered to assess patient’s cognitive functions.

Data analysis

Gender distribution, CDR scores, and the global rating of the BEHAVE-AD were examined for dif-ferences among patients with four types of dem-entia using χ2test. Differences in mean age and years of education among the four dementia types were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Scheffé

post hoc pairwise comparison. ANCOVA was

per-formed with covariates of CDR scores and the ages among the four dementia types to determine dif-ferences among the adjusted BEHAVE-AD total scores and subscales, using Scheffé method for post

hoc comparisons. Odds ratios of various subscales

were also computed for relative risks of using psy-chotropic medications and for high caregivers’ bur-den (patients whose global ratings of BEHAVE-AD were 2 or 3). Spearman correlations were used to explore relations among total scores or subscales

of the BEHAVE-AD, and for MMSE scores. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 8.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

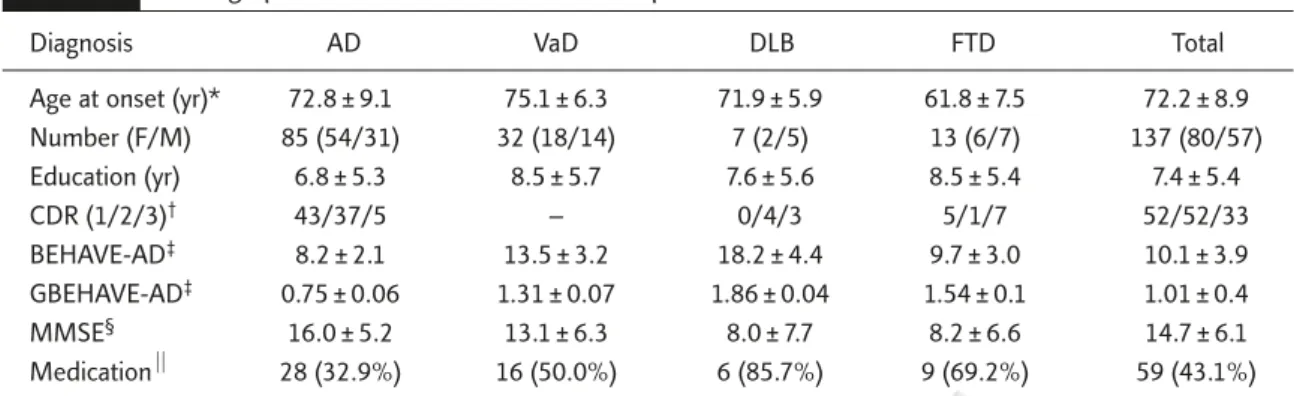

A total of 137 patients with four major types of de-mentia out of 155 patients treated at the clinic during the study period were included (Table 1). The prevalence of different dementia types in these patients were AD 54.8%, VaD 20.6%, FTD 8.4%, DLB 4.5%, and other dementias 11.6%. Patients in the heterogeneous category of “other dementias” were excluded from further analysis. There were no significant differences among pa-tients with different dementia types in the distri-bution of sex (χ2= 4.35, p = 0.226) and years of education (F = 0.91, p = 0.439). However, mean ages were significantly different among types (F = 8.36,

p < 0.001). Scheffé post hoc tests revealed that

patients with FTD were much younger than those with AD and VaD (both p < 0.001).

Scheffé post hoc tests also revealed a signifi-cant difference in MMSE score between patients with AD and FTD (F = 7.73, p < 0.001; Table 1). However, the presence of BPSD may have prohib-ited an adequate mental function test in some patients due to their uncooperative attitude. The high rate of failure to take or complete the MMSE,

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with dementia

Diagnosis AD VaD DLB FTD Total

Age at onset (yr)* 72.8 ± 9.1 75.1 ± 6.3 71.9 ± 5.9 61.8 ± 7.5 72.2 ± 8.9

Number (F/M) 85 (54/31) 32 (18/14) 7 (2/5) 13 (6/7) 137 (80/57) Education (yr) 6.8 ± 5.3 8.5 ± 5.7 7.6 ± 5.6 8.5 ± 5.4 7.4 ± 5.4 CDR (1/2/3)† 43/37/5 – 0/4/3 5/1/7 52/52/33 BEHAVE-AD‡ 8.2 ± 2.1 13.5 ± 3.2 18.2 ± 4.4 9.7 ± 3.0 10.1 ± 3.9 GBEHAVE-AD‡ 0.75 ± 0.06 1.31 ± 0.07 1.86 ± 0.04 1.54 ± 0.1 1.01 ± 0.4 MMSE§ 16.0 ± 5.2 13.1 ± 6.3 8.0 ± 7.7 8.2 ± 6.6 14.7 ± 6.1 Medication⏐⏐ 28 (32.9%) 16 (50.0%) 6 (85.7%) 9 (69.2%) 59 (43.1%)

*ANOVA with Scheffé post hoc, F = 8.36, p < 0.001; †χ2= 47.83 , p < 0.001; ‡ANCOVA adjusted with covariates of CDR scores and ages with Scheffé post hoc, F = 8.644, p < 0.001 for BEHAVE-AD, and F = 6.00, p < 0.001 for GBEHAVE-AD; §ANOVA with Scheffé post hoc, F = 7.73, p < 0.001; ⏐⏐χ2= 13.00, p = 0.005. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; VaD = vascular dementia; DLB = dementia of Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; F/M = female/male; CDR = clinical dementia rating; BEHAVE-AD = adjusted mean ± standard deviation of total scores; GBEHAVE-AD = adjusted mean ± standard deviation of global ratings of BEHAVE-AD; MMSE = mini mental state examination; Medication = percentages of patients receiving psychotropic medications.

especially in patients with DLB (57%) and FTD (33%), prevented further comparative analysis of MMSE data among groups.

The distribution of severity based on CDR scores among different types of dementia was not even (χ2= 47.83, p < 0.001). Thus, further analy-ses of the total scores or subscales of BEHAVE-AD were done with adjusted ages and CDR scores.

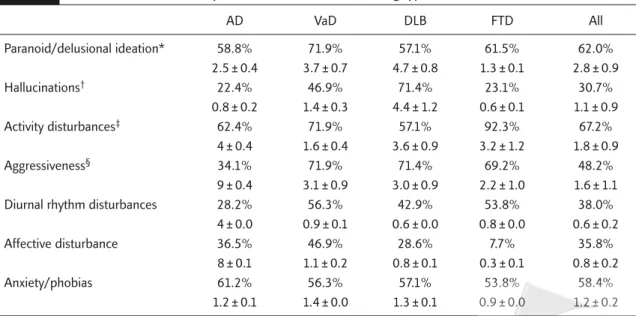

The most frequent symptom dimension noted among the subscales was activity disturbances. More than two-thirds (67.2%) of patients had activity problems in which purposeless activity took the lead (48.9%) followed by wandering (43.8%) and inappropriate activities (30.7%). The second most frequent symptom dimension was paranoid and delusional ideation (62.0%) in which suspiciousness/paranoia (42.3%) was the most frequently encountered manifestation fol-lowed by the delusion that “people are stealing things” (40.1%). The third most frequent symp-tom dimension was anxiety and phobias (58.4%) with the most common anxiety arising from up-coming events (36.5%). The fourth most frequent symptom dimension was aggressiveness (48.2%) in which verbal outbursts (36.5%) were more frequent than physical threats or violence

(16.1%). Affective disturbance (35.8%), either as tearful episodes (29.2%) or as depressed mood (21.2%), was also found in some patients. Hallucinations (30.7%), most frequently in the form of visual hallucinations or their verbal, physical or emotional responses (25.5%), were also not infrequently noted.

Clinical type-specific BPSD patterns were read-ily identified. DLB was associated with a high incidence of hallucinations (71.4%) and aggres-siveness (71.4%), FTD with a high incidence of activity disturbances (92.3%), AD with a high incidence of anxiety and phobias (61.2%) and VaD with a high incidence of paranoid and delu-sional ideation (71.9%) and affective disturbance (46.9%; Table 2).

ANCOVA with adjusted CDR scores and ages revealed significant between-subject effects of BEHAVE-AD total scores (F = 8.64, p < 0.001) among different types of dementia (Table 1). Scheffé post hoc test indicated that these differences were greatest in DLB out of the four dementia types and also that those for VaD were higher than for AD and FTD (all p < 0.001). Further analysis of the subscale data disclosed significant differences in aggressiveness (F = 11.10, p < 0.001), activity

Table 2. Relative incidence and adjusted subscales of BPSD among types of dementia

AD VaD DLB FTD All Paranoid/delusional ideation* 58.8% 71.9% 57.1% 61.5% 62.0% 2.5 ± 0.4 3.7 ± 0.7 4.7 ± 0.8 1.3 ± 0.1 2.8 ± 0.9 Hallucinations† 22.4% 46.9% 71.4% 23.1% 30.7% 0.8 ± 0.2 1.4 ± 0.3 4.4 ± 1.2 0.6 ± 0.1 1.1 ± 0.9 Activity disturbances‡ 62.4% 71.9% 57.1% 92.3% 67.2% 4 ± 0.4 1.6 ± 0.4 3.6 ± 0.9 3.2 ± 1.2 1.8 ± 0.9 Aggressiveness§ 34.1% 71.9% 71.4% 69.2% 48.2% 9 ± 0.4 3.1 ± 0.9 3.0 ± 0.9 2.2 ± 1.0 1.6 ± 1.1

Diurnal rhythm disturbances 28.2% 56.3% 42.9% 53.8% 38.0%

4 ± 0.0 0.9 ± 0.1 0.6 ± 0.0 0.8 ± 0.0 0.6 ± 0.2

Affective disturbance 36.5% 46.9% 28.6% 7.7% 35.8%

8 ± 0.1 1.1 ± 0.2 0.8 ± 0.1 0.3 ± 0.1 0.8 ± 0.2

Anxiety/phobias 61.2% 56.3% 57.1% 53.8% 58.4%

1.2 ± 0.1 1.4 ± 0.0 1.3 ± 0.1 0.9 ± 0.0 1.2 ± 0.2

*ANCOVA of subscales adjusted for CDR scores and ages (F = 3.11, p = 0.017) for paranoid/delusional ideation; †F = 7.09 and p < 0.001; ‡F = 8.36 and p < 0.001; §F = 11.10 and p < 0.001. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; VaD = vascular dementia; DLB = dementia of Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; % = incidence of subscales of BPSD in each subtype of dementia and in total number of patients; mean ± SD of subscales in different types of dementia and in total number of patients.

disturbances (F = 8.36, p < 0.001), hallucinations (F = 7.09, p < 0.001) and the paranoid/delusional ideation subscale (F = 3.11, p = 0.017). Post hoc tests showed that the hallucinations subscale score was highest in the DLB group, followed by VaD. The activity disturbance subscale score was also highest in DLB followed by FTD, although the rel-ative incidence of such behavior was highest in FTD. In contrast, FTD followed all other dementia types in scores both for affective disturbance and for anxiety/phobias subscales (both p < 0.001).

The mean total scores for the BEHAVE-AD were significantly different between patients re-ceiving (14.8 ± 8.8) and not rere-ceiving (6.5 ± 6.4) psychotropic medications (F = 41.44, p < 0.001). The relative risk of receiving psychotropic med-ications in symptom subscales represented by odds ratios were aggressiveness (2.81), para-noid/delusional ideation (2.24), hallucinations (2.12), diurnal rhythm disturbance (1.79), activ-ity disturbances (1.56), affective disturbance (1.28), and anxiety/phobias (1.07). Relative risk of high caregiver’s burden paralleled the risk of receiving psychotropic medications, with odds ratios in the order of aggressiveness (17.57), paranoid/delusional ideation (5.77), hallucina-tions (4.26), diurnal rhythm disturbance (4.00), activity disturbances (2.64), affective disturbance (1.85), and anxiety/phobias (1.40).

MMSE scores showed significant negative corre-lations with subscales of the BEHAVE-AD includ-ing activity disturbances (n = 105, Spearman rho

r =−0.358, p<0.001) and aggressiveness (r=−2.59, p < 0.001) but not with the total score (r =−0.155, p = 0.115). CDR was positively correlated with total

BEHAVE-AD (n = 137, Spearman rho r = 0.379, p < 0.001) as well as with subscales of aggressiveness (r = 0.410, p < 0.001), activity disturbances (r = 0.303,

p < 0.001), and hallucinations (r = 0.254, p = 0.003).

Discussion

FTD was characterized by much younger mean age of onset than AD and other types of dementia in this study, which is compatible with previous

observations.21The FTD patient with the earliest age of onset in this series was a 49-year-old male. DLB accounts for only 4.5% (7/155) of demen-tia cases in this study. Although this series of patients was from a memory clinic, its distribu-tion might not represent the prevalence of demen-tia in the general population. A previous study in the UK found DLB to be the second most common pathologic cause of dementia, comprising 20% of autopsy cases.22An epidemiologic study in sub-urban London found that DLB accounted for 10.9% of all types of dementias.23An inpatient-based study in Hong Kong, however, reported a low prevalence rate of 2.9% DLB among all dementias in a psychogeriatric population,24and a community-based study in a Japanese rural population found a DLB rate of 2.8%.25These findings suggest the possibility of ethnic differ-ences in the prevalence rate of DLB, but neuro-pathologic confirmation is required.

Although the manifestations of BPSD may be influenced by a variety of factors, they are pri-marily the results of underlying neurobiologic changes in the brain. Previous clinicopathologic correlation studies of BPSD had limited and in-conclusive findings. Paranoid/delusional ideation has been related to a temporal dysfunction.26 Neurobiologic studies of agitation and aggression uncovered several relationships. Functional imag-ing usimag-ing 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET showed that agitation and disinhibition correlated with de-creased frontal and temporal cortical metabolic rate.27The extent of white matter injury and the overall severity of the neuropsychiatric symptoms as well as severity and depression were also well correlated.28Left frontal lobe lesion has been pro-posed to be pathogenic for depression, especially the lesions of the left anterior frontal lobe.29

Previous studies found patients with AD often manifested motor behavior disturbance, aggres-siveness, mood disturbances, and psychotic symp-toms.30–33In this study, we found patients with AD had relatively increased incidence of anxiety and phobias. Transcultural or multiethnic studies suggested that these manifestations had ethnic, cultural, and social background dependencies.30–32

More apathy and depression were reported in western populations30,31in contrast to more activ-ity disturbances and aggressiveness in oriental patients.32,33However, such comparisons may be confounded by differences in clinical populations including various severities or differences in pro-fessional backgrounds of the interviewers.

One of the main findings of this study was the delineation of subtype-specific patterns of BPSD. For example, hallucination had the highest inci-dence and severity in patients with DLB. Recurrent visual hallucination is typically well-formed and is one of the essential core features of DLB in the con-sensus criteria of McKeith et al.17 Activity distur-bances were noted in almost all patients (92.3%) with FTD in this series, similar to a previous re-port.8 Nevertheless, the early appearance of im-paired language function in FTD could prevent the expression of some BPSD such as affective distur-bance, hallucinations or anxiety and phobias. On the other hand, affective disturbance was most fre-quently encountered in VaD (46.9%) in that nearly one out of two patients exhibited such problems.34 Patients with DLB had the highest mean total scores of BEHAVE-AD, caregiver’s burden, and inci-dence of receiving psychotropic medications. On the contrary, VaD had the highest scores in several subscales such as aggressiveness, diurnal rhythm disturbances or paranoid/delusional ideation in addition to the aforementioned affective distur-bance. VaD was not as aggressively treated as DLB and FTD. The discrepancy should be further elu-cidated. The presence of more caregiver-disturbing or stress-producing BPSD such as aggressiveness, paranoid/delusional ideation and hallucinations, was associated with more frequent prescription of psychotropic medications. This suggests that the main purpose of using psychotropic medications is to relieve the caregiver’s burden. In contrast, BPSD with lower odds ratios of high caregiver’s burden such as activity disturbances, affective dis-turbance and anxiety-phobias, could be more eas-ily handled by nonmedication methods.

The relationship between BPSD and cogni-tive deficits, either in terms of cognition or func-tional status in patients with dementia, was not

conclusive. However, psychotic symptoms, activity disturbances, and aggressiveness seemed to have an adverse effect on cognitive functions or vice versa.35 Although this study included a total of 137 of 155 patients with dementia who visited a memory clinic during the study period, the numbers of some dementia types such as DLB and FTD remained small due to their comparatively low incidence. This is a major limitation of this study and should be kept in mind when considering possible generalization of the findings.

Conclusion

The study found the subtype-specific BPSD in dif-ferent types of dementia including hallucination in DLB, activity disturbances in FTD, and affective disturbance in VaD. The relative risk of psycho-tropic medications was highly correlated with the severity of caregivers’ burden, indicating that caregivers’ burden prompted physicians to pre-scribe psychotropic medications for patients with dementia. Since nonpharmacologic interventions for BPSD are helpful for caregivers of patients with dementia, the need for different strategies of care-giving for patients with different types of dementia should be emphasized, including environmental stimulus control for DLB patients who are prone to having hallucinations, design of a pacing path for patients with FTD who need support for symp-toms of wandering, and emotional support for pa-tients with VaD who are susceptible to depression.

References

1. Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, et al. The cost of behav-ioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J

Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;7:403–8.

2. Cohen RF, Swanwick GRJ, O’Boyle CA, et al. Behavior dis-turbance and other predictors of caregiver’s burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;12:331–6. 3. Stell C, Rovner B, Chase GA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer’s patients. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1049–51.

4. Wilkinson D. How effective are cholinergic therapies in improving cognition in Alzheimer’s disease? In: O’Brien J,

Ames D, Burns A, eds. Dementia. Arnold: London, 2000: 549–69.

5. Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, et al. The behavior rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1349–57. 6. Molchan SE, Little JT, Cantillon M, et al. Psychosis. In: Lawlor BA, ed. Behavior Complications of Alzheimer’s

Disease. Washington, DC: American Psychiatry Press,

1995:55–76.

7. Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1996; 46:130–5.

8. Mendez MF, Perryman KM, Miller BL, et al. Behavioral differences between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison on the BEHAVE-AD rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr 1998;10:155–62.

9. Klatka LA, Louis ED, Schifer RB. Psychiatric features in dif-fuse Lewy body disease: a clinicopathologic study using Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease comparison groups. Neurology 1996;47:1148–52.

10. McKeith IG, Fairbairn AF, Bothwell RA, et al. An evaluation of the predictive validity and inter-rater reliability of clinical diagnostic criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type.

Neurology 1994;44:872–7.

11. Cummings JL, Miller B, Hill MA, et al. Neuropsychiatric aspects of multi-infarct dementia and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 1987;44:389–93.

12. Ballard C, Bannister C, Solis M, et al. The prevalence, asso-ciations and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disor 1996;36:135–44.

13. Pang FC, Chow TW, Cummings JL, et al. Effect of neuropsy-chiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease on Chinese and American caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:29–34. 14. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-Mental State’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of pa-tients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. 15. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical

diag-nosis of Alzheimer’s type: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurology 1984;34:939–44.

16. Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular de-mentia: diagnostic criteria for research studies: report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 1993; 43:250–60.

17. McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guide-lines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996;47:1113–24. 18. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal

lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998;51:1546–54.

19. Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, et al. Behavioral symp-toms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treat-ment. J Geriatr Psychiatry 1987;48:9–15.

20. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current ver-sion and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–4. 21. Neary D, Snowden JS, Northen B, et al. Dementia of

frontal lobe type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51: 353–61.

22. Perry RH, Irving D, Blessed G, et al. Senile dementia of Lewy body type. A clinically and neuropathologically distinct form of Lewy body dementia in the elderly. J Neurol Sci 1990; 95:119–39.

23. Stevens T, Livingston G, Kitchen G, et al. Islington study of dementia subtypes in the community. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:270–6.

24. Chan SSM, Chiu HFK, Lam LCW, et al. Prevalence of de-mentia with Lewy bodies in an inpatient psychogeriatric population in Hong Kong Chinese. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2002;17:847–50.

25. Yamada T, Hattori H, Miura A, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies in a Japanese population. Psychiatry Clin

Neurosci 2001;55:21–5.

26. Cummings JL. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1985.

27. Sultzer DL, Mahler ME, Mandelkern MA, et al. The relation-ship between psychiatric symptoms and regional metabo-lism in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiat Clin Neurosci 1995;7:476–84.

28. Sultzere DL, Mahler ME, Cummings JL, et al. Cortical abnor-malities associated with subcortical lesions in vascular dementia. Arch Neurol 1995;52:773–80.

29. Robinson RG, Chait RM. Emotional correlates of structural brain injury with particular emphasis on post-stroke mood disorders. Critic Rev Clin Neurobiol 1985;1:285–318. 30. Chen JC, Borson S, Scanlan JM. Stage-specific prevalence

of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease in a multi-ethnic community sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;8: 123–33.

31. Binetti G, Mega M, Magni E, et al. Behavioral disorders in Alzheimer disease: a transcultural perspective. Arch Neurol 1998;55:539–44.

32. Chow TW, Liu CK, Fuh JL, et al. Neuropsychiatric symp-toms of Alzheimer’s disease differ in Chinese and American patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:22–8.

33. Lam LCW, Tang WK, Leung V, et al. Behavioral profile of Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese elderly – a validation study of the Chinese version of the Alzheimer’s disease behavioral pathology rating scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16: 368–73.

34. Groves WC, Brandt J, Steinberg M, et al. Vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: is there a difference? A compar-ison of symptoms by disease duration. J Neuropsychiatr

Clin Neurosci 2000;12:305–15.

35. Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, et al. Relationship of behavioral and psychological symptoms to cognitive impairment and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease.