Clinical outcomes after interruption of entecavir therapy in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with compensated cirrhosis

Yi-Cheng Chen1, Cheng-Yuan Peng2, Wen-Juei Jeng1, Ron-Nan Chien3, Yun-Fan Liaw1

1 Liver Research Unit, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan

2 School of Medicine, China Medical University, Division of Hepatogastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan 3 Liver Research Unit, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and University, Keelung, Taiwan

Short title: Outcomes after cessation of ETV therapy in patients

Corresponding author

Prof. Yun-Fan Liaw Liver Research Unit

Chang Gung Memorial Hospital

199, Tung Hwa North Road, Taipei, 105 Taiwan

Tel: 886-3-3281200 ext. 8120 Fax: 886-3-3282824

e-mail: liveryfl@gmail.com

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma,

Summary

Background: Long-term nucleos(t)ide analogs therapy may reduce hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC) in chronic hepatitis B patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. Aim: This

retrospective-prospective study aimed to investigate whether this beneficial effect would be reduced in cirrhotic patients who discontinued a successful course of entecavir (ETV) therapy. Methods: The study included 586 hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative patients with compensated cirrhosis, mean age of 53.810 years and 81% males, treated with ETV for at least 12 months. After ETV therapy for 46.5±22.9 months, 205 patients who achieved hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA suppression discontinued therapy. The clinical outcomes were assessed and HCC incidence was compared between propensity score (PS)-matched patients who continued and patients who discontinued ETV therapy by APASL stopping rule.

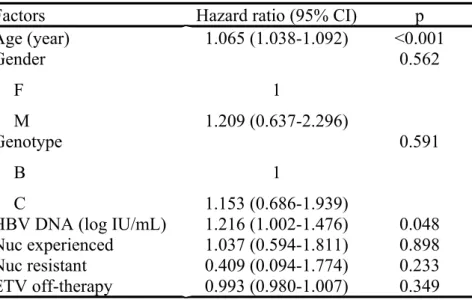

Results: During a mean duration of 59.319 months after start of ETV therapy, 9 and 6 HCC developed in an estimated annual incidence of 2.3% and 1.6% in 154 PS-matched patients who continued and who discontinued ETV therapy, respectively (p=0.587). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses showed that age (HR 1.065, p<0.001) and HBV DNA (HR 1.216, p=0.048) were the significant factors for HCC development. The rates of adverse clinical outcomes were comparable. Conclusions: The clinical outcomes, including HCC, after cessation of a successful course of ETV therapy in patients with compensated cirrhosis were comparable to those who continued therapy. The results suggest that this strategy of finite therapy is safe and a feasible alternative to indefinite therapy, especially in low resources setting.

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a major risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection [1-4]. The annual incidence of HCC was reported to be 2-6% in patients with cirrhosis, collectively estimated 5-year cumulative incidence to be 17% in East Asia and 10% in Western regions [5-7]. Studies have shown that lamivudine (LAM) treatment can reduce the incidence of hepatic decompensation and HCC in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, even in those with drug resistance [8-9]. With adefovir (ADV) rescue for LAM resistance, a review summarizing studies including those from Europe showed that the annual incidence of HCC was reduced as compared with LAM monotherapy [10]. The third generation nucleos(t)ide analog (Nuc), entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), are more potent than LAM and has no or very low incidence of drug resistance [11-13]. As expected, long-term ETV treatment was shown to be better than LAM in reducing HCC in HBV-related patients with cirrhosis [14]. Other

historical control study [15] or cohort studies tend to suggest that the incidence of HCC was reduced by ETV in Asian [16], but not adequately assessed with control group in European patients with cirrhosis [17]. A most recent review further showed that there was ~30% overall HCC risk reduction in patients with cirrhosis included in Asian studies with matched

untreated controls, but a lower HCC risk was not demonstrated in Caucasian studies comparing with natural history data [18].

For hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), indefinite or life-long Nuc therapy is recommended for patients with cirrhosis by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and the European

Association for the Study of Liver disease (EASL) guidelines [11,12]. Weighted against the potential problems of indefinite Nuc therapy such as adherence/persistence and

guidelines suggest that discontinuation of Nuc treatment can be considered after demonstration of undetectable serum HBV DNA on three separate occasions at least 6 months apart [13]. By this APASL stopping rule, recent studies have shown that ETV therapy can be safely stopped in cirrhotic patients if proper off-therapy monitoring is provided to restart therapy timely when needed [19,20]. Given the findings of remarkable fibrosis regression and even reversal of cirrhosis during 6-year (median) ETV therapy [21] or after 5-year TDF therapy [22], the outcomes, including HCC development, of ETV therapy for only 2-4 years were unknown and may be of clinical concerns. We therefore conducted this prospective-retrospective study in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with compensated cirrhosis to compare the HCC incidence between patients with continuing ETV therapy and those who had discontinued ETV therapy by the APASL stopping rule.

Methods

Study population

This prospective-retrospective study included a consecutive series of 586 HBeAg-negative CHB patients with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class A) who were treated with ETV 0.5mg daily for a minimum of 12 months at three medical centers, in which the principle investigators have same training background in the general management of CHB patients. Patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B and C), concurrent hepatitis C virus, delta virus or human immunodeficiency virus infection, alcoholic liver disease and autoimmune hepatitis were excluded. Patients with a history of HCC or who developed HCC within the first 12 months after initiation of ETV treatment were considered to have pre-existing HCC and therefore were excluded from the study. Patients were

anonymized and de-identified for data collection.

(“continued group”) and 205 had ever stopped ETV after achieving virological suppression (HBV DNA below detection limit of the PCR assay) at the discretion of their physicians. Among the 205 patients, 164 discontinued ETV by APASL stopping rule and these patients were selected as “discontinued group”. According to APASL guidelines, patients were retreated with ETV whenever HBV DNA 2000 IU/mL was detected regardless of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level [13]. The patient disposition is shown in Figure 1. Of the 586 ETV-treated patients, 185 were Nuc-experienced [LAM: 132, LAM with resistance: 15; LAM resistance rescued with ADV: 28; ADV: 11; telbivudine (LdT): 3; LdT with resistance: 1].

The propensity score (PS) matching method was used to reduce the significant differences between groups, as described elsewhere [14,23]. A PS was computed using multiple regression analysis. The variables used in the model included age, gender, genotype, Nuc-experienced, Nuc-resistant, baseline serum HBV DNA level and total follow-up period. We performed the optimal matching method or the nearest neighbor matching method within a range of 0.01standard deviation (SD) on the estimated PS of continuing and discontinuing ETV treatment patients[24].

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Surveillance, diagnosis and assays

The baseline was set at the time of starting ETV therapy. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made by histological findings in 397 of the 586 ETV treated patients. The remaining patients were diagnosed with repeated and consistent findings of ultrasonography (US) suggestive of cirrhosis [25] and supported by clinical features [26] such as thrombocytopenia (66 patients), esophageal/gastric varices (108 patients) or additional computed tomography (CT) findings

suggestive of cirrhosis (15 patients). All patients were HBeAg negative and anti-HBe positive at baseline. They were followed up every 3 months or more frequently if clinically indicated. Follow-up studies included clinical assessment, liver biochemical tests, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and US. When liver nodules with suspicion of HCC were detected by US, dynamic CT or magnetic resonance imaging was performed. HCC was diagnosed by histology/cytology or US findings plus AFP level >400 ng/mL [26], or imaging findings of enhanced arterial contrast uptake followed by washout in the portal venous phase and equilibrium phase or the criteria of dynamic imaging studies in generally accepted guidelines [27].

HBV genotype was determined using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the surface gene of HBV. Serum HBV DNA was assayed using Roche Cobas Amplicor HBV Monitor test (Roche COBAS TaqMan HBV Test, lower limit of detection: 69 or 1.84 log10 copies/mL; 12 or 1.08 log10 IU/mL, Roche Diagnostics, Pleasanton, California).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean SD and were compared with

independent student t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as number (%) and were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. Cumulative incidences of HCC development were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test. The patients were censored when development of HCC was confirmed or at the end of follow-up period in those with continuous ETV treatment and at the time of restarting ETV in patients who had ever stopped ETV. HCC developed within 12 months after restarting ETV treatment were included as an end point event of the “discontinued group” in the analyses. The incidence of HCC was compared between patients with continuous therapy (“continued group”) and those who had ever stopped ETV therapy by the APASL stopping rule

Variables such as age, gender, HBV genotype, serum HBV DNA level, experience of Nucs, Nuc resistance and treatment continuity were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for the assessment of significant factors for HCC development. Statistic procedures were performed by Statistics Package for social science (SPSS) software (version 17.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of the whole series of 586 patients with mean age of 53.810 years and 81% males, undetectable HBV DNA was achieved during ETV therapy in 96.6%. Varices bleeding occurred in 22 patients, ascites/spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in 30 patients, hepatic encephalopathy in 6 patients and liver disease-related death in 17 patients. HBsAg

seroclearance was documented in 3 patients who discontinued ETV therapy and in 2 patient who continued ETV therapy. Among 586 patients, HCC occurred in 81 (13.8%) and 37 of them developed between 1 to 3 years during follow-up. The 3-year and 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was 6.6% and 15.7%, respectively, with an estimated annual incidence of 2.98%. The incidence was significantly lower than a PS matched cohort of untreated patients with compensated cirrhosis [9.8%, p<0.001, data not shown].

A total of 205 patients have ever stopped ETV treatment, 164 were by APASL stopping rules (selected as “discontinued group”) and 41 were not. As shown in Table 1, the baseline clinical features and outcomes (including HCC development) of these two subgroups were comparable but the mean duration of ETV treatment and consolidation therapy were

significantly longer in patients who discontinued ETV by APASL stopping rule (30.3 vs 14.2 months, p<0.001 and 22.9 vs 8.2 months, p<0.001, respectively).

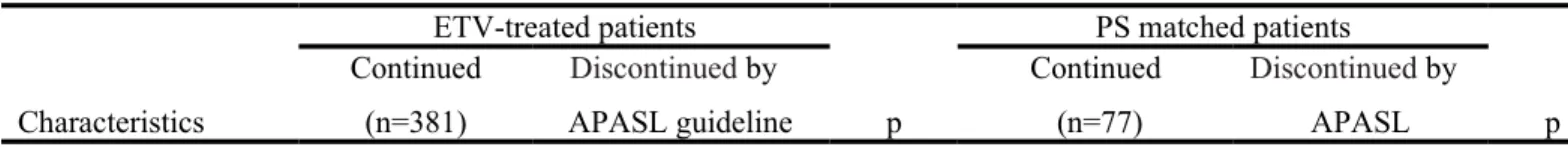

The clinical features and outcomes of the “continued group” and “discontinued group” are compared in Table 2. HCC developed in 65 (17.1%) of the 381 patients in the “continued group” with a 5-year cumulative incidence of 18.4% during a mean follow-up duration of 56.920.6 months. Of the 164 patients in the “discontinued group”, HCC developed in 12 (7.3%) patients with a 5-year cumulative incidence of 9.1% (p=0.008) during a mean follow-up duration of 54.620.6 months [Figure 2A]. The estimated annual incidence of HCC was 3.6% and 1.6% (p=0.004), respectively. PS-matching method performed for the difference in age, gender, HBV genotype, Nuc-experienced, Nuc-resistant, baseline HBV DNA level and follow-up period produced 77 patients each in the “continued” and “discontinued” group [Table 2]. Among the PS matched patients, the mean ETV treatment duration was 59.818.6 and 30.69.8 months in the “continued” and “discontinued” group, respectively (p<0.001). Of the PS-matched “discontinued” group, 41 patients restarted ETV treatment and 36 remained untreated with a mean off-ETV periods of 18.2 and 42.8 months, respectively (p<0.001). The clinical characteristics of these two subgroups are compared in Table 1. The mean duration of consolidation therapy was significantly shorter in retreated patients than those non-retreated (20.6 vs 25 months, p=0.027). Otherwise, there was no significant difference in age, gender, genotype, percentage of previous exposure to Nuc and Nuc-resistance, baseline HBV DNA level and ETV treatment duration [Table 1].

Among the 154 PS-matched patients, HCC developed in 9 (11.7%) patients of

“continued” group and in 6 (7.8%) of “discontinued” group (p=0.587) during a mean follow-up period of 59-60 months from the start of ETV therapy. Three of the 15 HCC patients occurred between 1 to 3 years during follow-up. Of the 6 HCC patients in the “discontinued group”, 4 developed in 36 patients who maintained HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL during post-treatment follow-up and remained untreated. The median ETV post-treatment duration and the time from the start of ETV therapy to HCC development was 32.1 (19.3-42.7) and 64

(50.8-83.1) months, respectively. The remaining 2 developed in 41 retreated patients 4-5 months after restart of ETV treatment. The ETV treatment duration and the time from the primary start of ETV therapy to HCC development were 18.7, 28.4 and 52.9, 37.8 months,

respectively. Nine of the 77 PS-matched patients in the “continued group” developed HCC after a median ETV treatment duration of 40.4 (24.2-46.2) months. The 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was 12.5% and 7.5%, respectively (p=0.182) [Figure 2B], and the estimated annual incidence was 2.3% and 1.6%, respectively (p=0.587) in “continued” and “discontinued” groups. The incidence between 9 (11.7%) HCC patients in 77 of PS-matched “continued group” and 4 (11.1%) in 36 non-retreated patients of PS-matched “discontinued group” was not different (p=1.000).

Of the whole group of 205 patients who had ever stopped ETV therapy, 87 patients (including 36 patients using APASL stopping rule) have never been retreated during a median/mean off-therapy follow-up of 33.8 (6.5-86.2)/39.8±22.2 months or a total follow-up duration of 67.6 (22.9-106.4)/69.8±19.8 months from the start of ETV therapy till their last visit. Nine of them developed HCC at 16.5 (7.2-55.2)/22.5±15.9 months after cessation of ETV therapy. The 5-year cumulative HCC incidence was 8.4% since the start of ETV therapy (1.75% per year) and 15.1% since the end of ETV therapy.

One hundred and 85 patients were Nuc-experienced among 586 ETV treated

compensated cirrhotic patients. The mean age (53.3 vs 54, p=0.414), gender (males 85.4 vs 78.8%, p=0.076), genotype (B 62 vs 61.3%, p=0.941) were comparable with Nuc-naïve patients, whereas mean baseline HBV DNA level was significantly higher (6.2 vs 5.7 log IU/mL, p<0.001) than Nuc-naïve patients. Among 185 Nuc-experienced patients, 44 (23.8%) were found Nuc resistant and 5 of them developed HCC after a median follow-up period of 53 (12.2-119.6) months. The 3-year and 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was 6.4% vs. 7.0% and 16% vs. 15.3% in Nuc-naive and Nuc-experienced patients, respectively (p=0.931

at 5 year). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of HCC between the Nuc-naive and Nuc-experienced patients (13.7 vs. 14.1%, p=1.000).

Associated factors with development of HCC

Factors associated with HCC development were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression model. In the analysis of the 586 patients with ETV treatment, age (HR 1.065, 95% CI 1.038-1.092, p<0.001) and baseline HBV DNA (HR 1.216, 95% CI 1.002-1.476, p=0.048) were the significant independent factors in multivariate analysis for the development of HCC [Table 3]. Gender, genotype, ETV off-therapy duration, Nuc resistance and Nuc-experienced treatment were not associated with the HCC development.

Discussion

The present study showed an estimated annual HCC incidence of 2.98% in 586 HBeAg-negative patients with compensated cirrhosis (mean age 53.8±10.0) treated with ETV for 2-5 years. The annual incidence of HCC in ETV-treated patients with cirrhosis was significantly reduced, as compared with that of the untreated controls. These results have confirmed the findings of earlier studies that around 3 years of ETV therapy significantly reduced HCC as compared with LAM therapy or untreated controls in Asian studies [14,15].

In untreated patients with cirrhosis, the 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was calculated to be 17% in East Asia and 10% in Western regions [7]. The 5-year cumulative HCC incidence of 15.7% in our patients (62% genotype B, 38% genotype C, mean age 53.8 years) treated with ETV for a median period of 54.4 months seems lower than 19.1% in Korean patients with compensated cirrhosis (all genotype C, mean age 47.7 years) treated with ETV for a median of 37 months [16]. However, it was higher than 10.9% in patients with cirrhosis (mainly genotype A and D, mean age 51 years) treated with ETV for a median

of 167 weeks in Caucasians, as reported in a recent European multicenter real-life cohort study [17]. Perhaps the differences in the main HBV genotype(s) and ethnic origin are among the reasons for this difference across studies. Of note is that all studies comparing with untreated control patients invariably show significant reduction in HCC development [14,15,28]. However, there is seemingly no such benefit in the European cohort [17] when compared with the natural history data of patients with great different age [7]. Then, well matched controlled studies in European patients are warranted to confirm or refute the notion that long-term HBV suppression by Nuc therapy may reduce HCC development in patients with cirrhosis.

Perhaps the most important finding of the present study is that the beneficial effects of ETV therapy did not reduced in HBeAg-negative patients with compensated cirrhosis who discontinued a 2-4 year successful course of ETV therapy by the APASL stopping rule. This approach did not increase the risk of HCC as compared with the risk in patients who

continued ETV therapy of longer duration (5-year cumulative incidence 7.5 vs 12.5%, p=0.182) [Table 2 and Figure 2B]. In particular, the 5-year cumulative incidence (8.4%) did not increase in the 87 of the 205 patients who had never been retreated for up to 86 months off therapy. Age and baseline HBV DNA were the significant independent factors for the development of HCC in ETV treated patients, whereas ETV off-therapy was statistically insignificant [Table 3]. Among the 77 patients of PS-matched “discontinued group”, 36 non-retreated patients had comparable ETV treatment duration to but significantly longer

consolidation therapy period than the 41 retreated patients. The latter finding was similar to the observation by Chi that prolongation of consolidation therapy decreased the risk of virological relapse [29]. Furthermore, shorter off-ETV therapy period with early virological relapse (>2000 IU/mL) prompted early ETV retreatment in the 41 patients and therefore the incidence of HCC in the retreated subgroup (4.9%) did not increase when compared to the

non-retreated subgroup (11.1%, p=0.410) [Table 1]. In addition, the incidence of HCC in PS-matched “continued group” (9/77, 11.7%) under virological suppression was comparable to that in non-retreated subgroup of PS-matched “discontinued group” with HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL till last visit (4/36, 11.1%) (p=1.000). These findings suggest that the benefit of a successful finite course of ETV therapy in reducing HCC may sustain as long as HBV DNA remains below 2000 IU/mL.

It has been shown that fibrosis regression was demonstrated in up to 59% at 1 year [21,30] and 85% at 3 year [31] during ETV therapy and 60-74% at 3 to 5 year during LAM, ADV or TDF therapy [22, 32] in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. This may be one of the reasons for the long-term beneficial effect observed in patients who were treated with ETV for only 2-4 years in the present study. Actually, the effect of ETV therapy on HCC incidence in earlier studies became evident (during 2.3-4.3 years) before a significant fibrosis regression is expected [14,15], implicating that some elements in the carcinogenesis may be independent of liver pathology [18]. Anyway, this finding adds support to the APASL guidelines that cessation of Nuc therapy can be considered after a successful course of therapy in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with or without cirrhosis [13]. Of note is that the incidences of adverse clinical outcomes in the PS-matched patients who stopped ETV therapy were similar to those with continued ETV therapy [Table 2]. Taken together, this strategy of finite ETV therapy is safe and effective [18,19,33,34] if proper off-therapy monitoring plan offered, and can be considered as a feasible alternative to indefinite Nuc therapy. This strategy is particularly important for low resources countries where cost/reimbursement is a problem and where Nucs with high resistance are still used in substantial number of patients, not only in Asian countries including rich Singapore [35,36] but also in some European countries such as Poland and Turkey in up to 45% of the patients [37].

study comparing within the treated patients using PS matching method. Given the AASLD and EASL recommendation of indefinite or even lifelong Nuc therapy for patients with cirrhosis [11,12], a randomized controlled study is not possible and comparing with a PS matched control group may be the second best approach. Second, because limited patients discontinued ETV by APASL stopping rule, the patient number after PS matching method was relatively small in both “continued” and “discontinued” groups. In addition, PS matching method excluded some patients who developed HCC between one to three years during follow-up period and might lead to study bias. However, the results of the present study have provided a basis for the future prospective randomized control study to test the beneficial efficacy on reducing HCC development between indefinite and finite Nuc therapy. Third, the off-therapy follow-up period in “discontinued” group may be too short because 58% of the patients were retreated with ETV when off-therapy HBV DNA >2000 IU/mL was detected. However, analyses in a subset of 87 patients who had never received off-therapy retreatment showed a comparable 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC during a median off-therapy follow-up of 33.8 (6.5-86.2) months. Fourth, some patients did not have sufficient stored serum for retrospective assays of HBV genotype, HBsAg level and genomic mutations. Our recent study showed that basal core promoter double mutation was a factor for cirrhosis, not directly for HCC development [38].

In conclusion, ETV treatment could reduce the incidence of HCC in HBeAg-negative CHB patients with compensated cirrhosis. More importantly, the beneficial effect in reducing incidence of HCC did not decreased after cessation of a successful course of ETV treatment by the APASL stopping rule during a median observation duration of 45 months. Then, cessation of a successful course of Nuc therapy in patients with cirrhosis is a feasible

alternative strategy, which is also safe if timely retreatment is provided in case of virological relapse.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial and personal relationships with other people or

organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) their work. YF Liaw has involved in clinical trials or served as a global advisory board member of Roche.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the long-term grant support provided by Chang Gung Medical Research Fund (SMRPG1005, OMRPG380061, CMRPG3A0901) and the Prosperous Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan; Ms Li-Hua Lu for laboratory work, Ms Yu-Ju Lan for data collection, and Ms Su-Chiung Chu for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Authorship

Guarantor of article: Yun-Fan Liaw

Specific author contributions:

Yi-Cheng Chen: acquisition of data, first draft of the manuscript, statistic analysis Cheng-Yuan Peng: study concept, acquisition of data

Wen-Juei Jeng: acquisition of data

Rong-Nan Chien: study concept, acquisition of data

Yun-Fan Liaw: study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, material support, study supervision

References

1. Liaw YF, Lin DY, Chen TJ, Chu CM. Natural course after the development of cirrhosis in patients with chronic type B hepatitis: a prospective study. Liver 1989;9:235-241. 2. Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus: the major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer

1988;61:1942-1956.

3. Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, et al. REVEAL-HBV Study Group. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65-73.

4. Chen YC, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Age-specific prognosis following HBeAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;51:435-444.

5. Chu CM, Liaw YF. Hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis: natural history and treatment. Semin Liver Dis 2006;26:142-152.

6. Chen YC, Chu CM, Yeh CT, Liaw YF. Natural course following the onset of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a long-term follow-up study. Hepatol Int

2007;1:267-273.

7. Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol 2008;48:335-352. 8. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, et al. Lamivudine for patients

with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1521-1531.

9. Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Wong VW, Li KC, Chan HL. Meta-analysis: treatment of hepatitis B infection reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2008;28:1067-1077.

10. Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the long term outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Liver Dis 2013;17:413-423.

11. Lok A, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 2009;50:1-36. 12. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines:

Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2012;57:167-185. 13. Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Chan HLY, Chien RN, Liu CJ, et al. Asian-Pacific

consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int 2012;6:531-561.

14. Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 2013;58:98-107.

15. Wong GL, Chan HL, Mak CW, Lee SK, IP ZM, Lam AT, et al. Entecavir treatment reduces hepatic events and deaths in chronic hepatitis B patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2013;58:1537-1547.

16. Kim SS, Hwang JC, Lim SG, Ahn SJ, Cheong JY, Cho SW. Effect of Virological Response to Entecavir on the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Viral Cirrhotic Patients: Comparison Between Compensated and Decompensated Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1223-1233.

17. Arends P, Sonneveld MJ, Zoutendijk R, Carey I, Brown A, Fasano M, et al. Entecavir treatment does not eliminate the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: limited role for risk scores in Caucasians. Gut 2015;64:1289-1295.

18. Papatheodoridis GV, Chan HL, Hansen BE, Janssen HL, Lampertico P. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: Assessment and modification with current antiviral therapy. J Hepatol 2015;62:956-967.

19. Jeng WJ, Sheen IS, Chen YC, Hsu CW, Chien RN, Chu CM, et al. Off therapy durability of response to Entecavir therapy in hepatitis B e antigen negative chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology 2013;58:1888-1896.

20. Sohn HR, Min BY, Song JC, Seong MH, Lee SS, Jang ES, et al. Off-treatment virologic relapse and outcomes of retreatment in chronic hepatitis B patients who achieved complete viral suppression with oral nucleos(t)ide analogs. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:439.

21. Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;52:886-893. 22. Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, et al. Regression of

cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468-475.

23. Kumada T, Toyoda H, Tada T, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, et al. Effect of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy on hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis B patients: A propensity score analysis. J Hepatol 2013;58:427-433.

24. Austin PC. Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulations. Biom J 2009;51:171-184.

25. Lin DY, Sheen IS, Chiu CT, Lin SM, Kuo YC, Liaw YF. Ultrasonographic changes of early liver cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B: a longitudinal study. J Clin Ultrasound 1993;21:303-308.

26. Liaw YF, Tai DI, Chu CM, Lin DY, Sheen IS, Chen TJ, et al. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic type B hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1986;90:263-267.

27. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-1022.

28. Singal AK, Salameh H, Kuo YF, Fontana RJ. Meta-analysis: the impact of oral anti-viral agents on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:98-106.

29. Chi H, Hansen BE, Yim C, Arends P, Abu-Amara M, van der Eijk AA, et al. Reduced risk of relapse after long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue consolidation therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:867-876.

30. Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, Chao YC, Sette H Jr, Janssen HL, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2776-2783.

31. Yokosuka O, Takaguchi K, Fujioka S, Shindo M, Chayama K, Kobashi H, et al. Long-term use of entecavir in nucleoside-naïve Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol 2010;52:791-799.

32. Marcellin P, Asselah T. Long-term therapy for chronic hepatitis B: Hepatitis B virus DNA suppression leading to cirrhosis reversal. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:912-923.

33. Patwardhan VR, Sengupta N, Bonder A, Lau D, Afdhal NH. Treatment cessation in noncirrhotic, e-antigen negative chronic hepatitis B is safe and effective following prolonged anti-viral suppression with nucleosides/nucleotides. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:804-810.

34. Chang ML, Liaw YF, Hadziyannis SJ. Systematic review: cessation of long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:243-257.

35. Liaw YF. Antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B: opportunities and challenges in Asia. J Hepatol 2009;51:403-410.

36. Lim SG, Aung MO, Chung SW, Soon CS, Mak BH, Lee KH. Patient preferences for hepatitis B therapy. Antivir Ther 2013;18:663-670.

Chronic hepatitis B monitoring and treatment patterns in five European countries with different access and reimbursement policies. Antivir Ther 2014;19:245-257.

38. Chu CM, Lin CC, Chen YC, Jeng WJ, Lin SM, Liaw YF. Basal core promoter mutation is associated with progression to cirrhosis rather than hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Br J Cancer 2012;107:2010-2015.

Figure legends

Figure 1. Disposition of the patients with compensated cirrhosis who continued and discontinued entecavir (ETV) therapy. Among the 586 ETV-treated compensated cirrhotic patients, 381 with continuing ETV and 205 with ETV cessation. Propensity score matching method performed to continued and discontinued groups produced 77 patients in each group. HCC developed in 9 and 6 patients of continued and discontinued group, respectively

(p=0.587). ETV cessation: after achieving HBV DNA suppression (undetectable). APASL stopping rules: undetectable HBV DNA on 3 separate occasions at least 6 months apart. Retreat (+): restart ETV when HBV DNA 2000 IU/mL regardless of ALT level. Retreat (-): follow-up HBV DNA <2000 IU/mL after cessation of ETV.

Figure 2. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of HCC between patients “continued” (solid line) and “discontinued” (broken line) entecavir (ETV) therapy. [A]. All patients; [B]. Propensity score matched patients. The reference starting point is beginning of ETV treatment. The 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was 18.4% and 9.1% in 381 continued patients and 205 ETV-discontinued patients, respectively (p=0.008) in overall patients. Under propensity score matching method, the 5-year cumulative incidence of HCC was 12.5% and 7.5% in 77 continued and discontinued patients, respectively (p=0.182).

Table 1. The clinical characteristics and comparison between patients discontinued ETV therapy by APASL rule and those not and between retreated and non-retreated patients in PS-matched discontinued group

Cessation of ETV (n=205) PS-matched discontinued group (n=77) Characteristics APASL guideline yes (n=164) APASL guideline no (n=41) p Non-retreated (n=36) Retreated (n=41) p Age(y) 53.49.6 54.48.7 0.562 50.97.8 54.19.3 0.112 Gender Male Female 138(84.1) 26(15.9) 36(87.8) 5(12.2) 0.733 33(91.7) 3(8.3) 37(90.2) 4(9.8) 1.000 Genotype B C 96(65.8) 50(34.2) 32(80) 8(20) 0.126 21(58.3) 15(41.7) 31(75.6) 10(24.4) 0.170 Nuc- experienced 71(43.3) 16(39) 0.751 14(38.9) 15(36.6) 1.000 Nuc- resistant 20(12.2) 4(9.8) 0.791 2(5.6) 4(9.8) 0.679 Platelet 144.448.6 133.961.9 0.459 160.860.7 141.141.6 0.368 HBV DNA 5.91.5 5.91.4 0.981 6.01.3 6.01.3 0.941 ETV treatment duration (m) 30.310.8 14.22.1 <0.001 32.39.2 29.110.2 0.157 Consolidation therapy (m) 22.910.7 8.22.1 <0.001 25.09.4 20.67.5 0.027 Off-ETV period (m) 25.518.6 38.328.2 0.001 42.818.4 18.211.7 <0.001 Follow-up(m) 54.620.6 48.826.0 0.130 72.416.7 46.712.9 <0.001 Retreatment 92(56.1) 26(63.4) 0.502 Varices bleeding 7(4.3) 1(2.4) 1.000 0 0 Ascites 6(3.7) 1(2.4) 1.000 0 0 Encephalopathy 0(0) 0(0) 0 0 HCC 12(7.3) 4(9.8) 0.532 4(11.1) 2(4.9) 0.410 Death 1(0.6) 1(2.4) 0.361 0 0

ETV: entecavir; PS: propensity score; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Nuc, nucleos(t)ide analogue; HBV DNA, log IU/mL

Table 2. The baseline demographics and outcomes of overall and propensity score matched patients who continued and those discontinued (by APASL guideline) ETV treatment

ETV-treated patients PS matched patients Characteristics Continued (n=381) Discontinued by APASL guideline p Continued (n=77) Discontinued by APASL p

(n=164) guideline (n=77) Age(y) meanSD 53.910.3 53.49.6 0.579 54.09.9 52.68.7 0.380 Gender Male Female 300(78.7) 81(21.3) 138(84.4) 26(15.9) 0.180 67(87) 10(13) 70(91) 7(9) 0.607 Genotype B C 184(57.7) 135(42.3) 96(65.8) 50(34.2) 0.121 57(74) 20(26) 52(67.5) 25(32.5) 0.478 Nuc- experienced 98(25.7) 71(43.3) <0.001 28(36.4) 29(37.7) 1.000 Nuc- resistant 20(5.2) 20(12.2) 0.008 4(5.2) 6(7.8) 0.744 Platelet 121.853.2 144.448.6 0.001 129.051.9 149.250.5 0.104 HBV DNA meanSD 5.81.4 5.91.5 0.744 6.11.3 6.01.2 0.464 ETV treatment duration (m) 56.920.6 30.310.8 <0.001 59.818.6 30.69.8 <0.001 Follow-up(m) meanSD 56.920.6 54.620.6 0.230 59.818.6 58.719.5 0.724 Varices bleeding 14(3.7) 7(4.3) 0.930 1(1.3) 0 1.000 Ascites 22(5.8) 6(3.7) 0.415 2(2.6) 0 0.497 Encephalopathy 6(1.6) 0(0) 0.185 0 0 HCC 65(17.1) 12(7.3) 0.004 9(11.7) 6(7.8) 0.587 Death 15(3.9) 1(0.6) 0.049 3(3.9) 0 0.245

ETV: entecavir; PS: propensity score; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Nuc, nucleos(t)ide analogue; HBV DNA, log IU/mL

Table 3. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for factors associated with HCC development in ETV treated patients with compensated cirrhosis

Factors Hazard ratio (95% CI) p

Age (year) 1.065 (1.038-1.092) <0.001 Gender F M 1 1.209 (0.637-2.296) 0.562 Genotype B C 1 1.153 (0.686-1.939) 0.591

HBV DNA (log IU/mL) 1.216 (1.002-1.476) 0.048 Nuc experienced 1.037 (0.594-1.811) 0.898 Nuc resistant 0.409 (0.094-1.774) 0.233 ETV off-therapy 0.993 (0.980-1.007) 0.349

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; PS: propensity score;CI: confidence interval; Nuc: nucleos(t)ide analog; ETV: entecavir