國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

亞裔美國圖像敘事中的刻板印象與身份認同

Stereotyping and Identity Formation in

Asian American Graphic Narratives

研究生: 鍾政益

指導教授: 馮品佳 博士

亞裔美國圖像敘事中的刻板印象與身份認同

Stereotyping and Identity Formation in

Asian American Graphic Narratives

研究生:鍾政益 Student: Chen Yee Choong

指導教授:馮品佳 博士 Advisor: Dr. Pin-chia Feng

國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Department of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

College of Humanities and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University

In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts

in

Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

August 2014

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China.

中華民國一○三年八月

中

華

民

國

一

○

三

年

八

月

亞裔美國圖像敘事中的刻板印象與身份認同

研究生:鍾政益 指導教授:馮品佳 博士

國立交通大學外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

中文摘要

本文藉著分析四本圖像敘事:《美國早期漫畫中的華人》(1995)、《美生中國 人》(2006)、《短處》(2007)及《秘密身份:亞裔美國超級英雄選集》(2009)來 探討亞裔美國之刻板印象與身份認同。這四本圖像敘事不但反映出紮根在美國文 化中的種族主義,也展現此意識形態對於亞裔美國人身份認同與主體性形成的深 刻影響。 第一章簡介本文中心題旨、動機及圖像敘事之生成脈絡。文中檢視圖像敘事 這一新興文類之重要性和侷限性,並探討此文類如何輔助亞裔美國文學研究。文 中對圖像進行深入剖析,點出其特性與敘事運用手法與機制,藉此指出圖像與文 字敘事相異之處。 第二章著重於解構種族刻板印象。通過檢視美國十九世紀流行之族裔諷刺畫, 此篇提及刻板印象之行徑與戀物癖相似,兩者皆藉由戀物之方式緩和閹割焦慮。 在移民頻繁的時代,刻板印象乃美國白人之「戀物」。通過刻板印象之塑造,美 國白人得以維護其備受「種族他者」威脅之主體性與主導權。 第三章藉由分析《美生中國人》和《短處》來揭示亞裔美國人如何在種族主 義下被建構成「永恆的他者」,同時也檢視此意識形態對於亞裔美國人身份認同 與主體性之影響。文中揭示美國主體性之形成與種族主義之密切關係,故導致美 國國家想像之排他主義。《美生中國人》及《短處》中則以種族閹割之形式來凸 顯亞裔美國人在國家體系中之窘境。 本文以弗洛伊特臨床試驗作結尾,其對戀物癖之剖析不但強調母親陰莖之非 存在性,還揭示母親之陰莖實為想像物。如刻板印象、甚至種族之概念乃與「戀 物癖」屬同性質;同理,種族論述也應為人造之想像物。此類論述不但將身份以 種族的方式本質化,還助長白人對亞裔美國人(與非白人)之象徵暴力,剝奪後者 之身份認同與主體性。故此,亞裔美國圖像敘事提倡以異質性之架構審視身份與 主體性之建構,呵責種族主義之身份二分法。 關鍵字:亞裔美國研究、圖像敘事、族裔諷刺畫、霍米.巴巴、刻板印象、戀物 癖、身份認同、真理政權、種族主義、伊底帕斯情結、種族閹割、男子氣、異質 性Stereotyping and Identity Formation in

Asian American Graphic Narratives

Student: Chen Yee Choong Advisor: Dr. Pin-chia Feng Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

This thesis is an explication of Asian American stereotypes and identity formation. Focusing on four graphic narratives—The Coming Man: 19th Century American Perceptions of the Chinese (1995), American Born Chinese (2006),

Shortcomings (2007), and Secret Identities: the Asian American Superhero Anthology (2009)—my thesis intends to destabilize racism and the stereotypical representations of Asian American. By studying the graphic representation and experience of Asian Americans in these graphic narratives, I argue that racism is at the core of the

American culture, poignantly impacting the identity formation of the Asian American subjects.

Chapter One is an introduction which reviews the significance of graphic

narratives to justify how graphic narratives—as an emerging genre—contribute to the field of Asian American studies. In addition, the first chapter also provides the

definition of “Asian American graphic narratives” as well as the perimeters and limitations of my thesis to justify my choice of texts. Chapter One then proceed to discuss the difference between the Saussurian “system of language” and “system of image,” the characteristics of the image and how meaning is generated and contained in visual narratives.

Chapter Two aims to deconstruct ethnic stereotypes. By examining some of the earliest ethnic caricatures from the nineteenth-century American periodicals and newspapers, I argue that stereotypes are the fetishistic objects constructed to ensure the more general defense of a threatened Anglo-Saxon subjectivity in a time when immigration was profuse and to justify the white’s dominance over the ethnic others. Chapter Three examines how racism construes Asian people as the perpetual figure of xenos whilst exploring the impact of racism on the subjectivity and identity of the Asian American subject. Racism not only plays an important role in delineating the national space of the United States but it also enforces limitation and restriction on Asian Americans, thereby symbolically excluding them from the national

imagination—as exemplified in American Born Chinese and Shortcomings. The final chapter concludes this thesis with a discussion of Sigmund Freud’s clinical picture of the fetish. By emphasizing that the mother’s absent penis is merely a constructed object, I argue that stereotyping, racialized discourse, as well as the concept of race are manmade artifacts invented to reduce identity within the relation field of ethnic distinctions—white/non-white—and to impose symbolic violence on the ethnic others. It is only by situating them in multiple subject positions of a

heterogeneous framework can Asian Americans reclaim their subjectivity and identity.

Key Words: Asian American Studies, Graphic Narratives, Ethnic Caricatures, Homi K. Bhabha, Ethnic Stereotypes, Fetishism, Castration Anxiety, Identity Formation, Regime of Truth, Racism, Oedipal Complex, Racial Castration, Masculinity, Heterogeneity

Acknowledgements

Writing a thesis is never an easy task. It appears evidently so for me as my journey of thesis writing was constantly plagued by indolence, self-doubt, and enticements alike; but, fortunately, I was never alone throughout the course of my thesis writing. My advisor, the committee members of my thesis, friends, and family have not only offered guidance and companionship throughout this journey but their encouragements and sheer faith in me have been a pivotal element in the completion of my dissertation. Without them, I would never been able to complete my thesis.

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my advisor—Prof. Pin-chia Feng—who has supported me with her patience and

instruction throughout my thesis whilst allowing me the freedom to work in my own way. Her advice and vast knowledge in the field of Asian American studies are immensely helpful and invaluable. I could not simply wish for a better and friendlier advisor.

A million thanks to Prof. Shyh-Jen Fuh. I had drawn many of my inspiration from her class. It is a shame that she was unable to be a part of my oral defense. Additionally, I am immensely grateful to Prof. Ying-Hsiung Chou and Prof. Shih-Szu Hsu—who both were the committee members of my oral defense. Their insightful opinions and instructions had helped improve my dissertation.

Special thanks to my classmates at Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics of NCTU—most notably, Yu-Jung Yen, Sébastian Chuang, Michelle Chiu Yu, Alice Hung, Christopher Liao, and Ruth Chang—for bringing excitement and laughter to our lab. School life would be less interesting without them. The same goes to my best friends in Malaysia and Singapore as well—Kai Xiang Yoong, Ke Yang Siow, Khen Wei Cheong, and Yong Sen Yap. Your friendship and companionship are a blessing to me.

Likewise, I would like to thank my girlfriend—Alice Hsu Hanyun—who was always willing to help and give me her best advices. She had always been there to share my frustration and excitement throughout good times and bad. My life in Taiwan would be a lot different without her.

Last but not least, I am greatly indebted to my parents and my two younger sisters. Their unconditional love and support are my greatest motivation.

中文摘要 ... I

ABSTRACT ... II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... III

CHAPTER I. RHETORIC OF ASIAN AMERICAN GRAPHIC NARRATIVES ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

THEORIZING GRAPHIC NOVELS ... 2

THE COMING MAN AND ASIAN AMERICAN GRAPHIC NARRATIVES ... 6

RHETORIC OF GRAPHIC NARRATIVES ... 7

THE ORGANIZATION OF MY THESIS PROJECT ... 20

CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 26

CHAPTER II. DRAWING AND CONTAINING ANXIETY: ETHNIC CARICATURES, STEREOTYPES, AND ANGLO-SAXON PURITY ... 28

THE FEAR OF DISPOSSESSION ... 30

“REGIME OF TRUTH”:RACIALIZED KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES ... 38

THE MANY FACES OF CHIN-KEE: THE PERSISTENCE OF ETHNIC STEREOTYPES ... 48

CONCLUSION:ETHNIC STEREOTYPES AND ITS IMPACTS ON ASIAN AMERICAN ... 53

CHAPTER III. JOURNEY IN THE WEST: RACISM, NATIONAL IDENTITY, AND ASIAN AMERICAN MASCULINITY ... 55

ASHOELESS INTRUDER... 56

THE MAKING OF THE OTHER:RACISM AT WORK ... 59

BEFORE AND AFTER 1965: FROM MISS COLUMBIA’S SCHOOL TO MAYFLOWER ELEMENTARY.... 63

THE “BASTARD SON” OF AMERICA ... 66

RACIAL CASTRATION:WHY DOES THE “CAUC” MATTER? ... 69

SYMBOLIC EMASCULATION AND THE FEARS OF MISCEGENATION ... 73

CONCLUSION:TORN BETWEEN DANNY AND CHIN-KEE ... 79

CONCLUSION: ... 83

SUBVERTING WHITE FANTASY AND RECLAIMING ASIAN AMERICAN SUBJECTIVITY ... 83

Chapter I

Rhetoric of Asian American Graphic Narratives

Introduction

“…the picture-story, which critics disregard and scholars scarcely notice, has had great influence at all times, perhaps even more than written literature…”

--Rudolphe Töpffer (1799-1846) Understanding comics is serious business.

--Scott McCloud This thesis project attempts to explicate Asian American stereotypes and the identity formation. The formation of one’s identity and subjectivity are intensely affected by one’s perception of his self-image. Amid the process of identity-shaping, one draws on notions and perceptions that define his relationship with the milieu around him. Functioning primarily as an educational tool and a device of social networking, the mass media is replete with these social perceptions and notions that help us to make sense of ourselves and our relationships with others. It presents to one, from a seemingly normative point of view, the “necessary” and “neutral” information of a given society. Since it is deemed neutral, mass media is assumed to be

unproblematic and often left unquestioned. Scholars like Benedict Anderson, however, observes that media creates an illusion of proximity which “may mask our actual lack of contextual knowledge and understanding of our material relationships with others” (3). Put differently, mass media is not intrinsically unbiased because film, television, radio, music, the Internet, newspaper, magazines, and advertisements are social products that teemed with dominant readings and interpretations. The mass media, which are saturated with dominant opinions, hence function as a controlling social

power for the ruling class to gain control over the underclass.1

The practice of stereotyping is an example among all these notions and perceptions as it is a socially constructed artifact. The popular visual culture in our society is replete with the usage of stereotypes. Albeit a seemingly abstract perception, it is powerful enough to alter one’s position in the society, not to mention his identity and subjectivity which are so heavily related to his surroundings. In view of how the popular visual culture is pervaded with stereotypes, I would like to adopt four graphic narratives as my entry point to delve into the problems I raised. Focusing on The Coming Man: 19th Century American Perceptions of the Chinese (1995), American Born Chinese (2006), Shortcomings (2007), and Secret Identities: the Asian American Superhero Anthology (2009), my thesis attempts to destabilize racism and the

stereotypical myth of Asian American. By studying the visual representation and experience of Asian Americans in these graphic narratives, my thesis then proceeds to explore the identity formation of Asian American and its subjectivity.

Theorizing Graphic Novels

A huge bombshell was dropped in the literary field with the publication of Maus in 1991, evoking a great resonance within. Though my rhetoric might be slightly exaggerated, there is no denying that more attention is henceforth shifted to the graphic narrative, “which critics [used to] disregard and scholars scarcely notice” before Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece (McCloud 201). In his groundbreaking graphic novel, Spiegelman recounts his father’s experience as a Holocaust survivor during World War II through the medium of comics. Despite tackling with the complex narrative form of memoir, neither Spiegelman’s iconograph nor his narration has

1

The idea of how mass media functions as an ideological apparatus will be discussed extensively in the next chapter.

failed to present to his reader every possible detail and information. In addition, not only does the graphic novel lend itself well to the narrative form of memoir, but it is also suited for the use of autobiography, biography, nonfiction, travel, history, and even poetry including an ingenious adaptation of T.S. Elliot’s The Waste Land (1999) by Martin Rawson.

Yet, even though Maus is a major success and enjoys a world-wide reputation, graphic narrative is not a newly-invented genre. In fact, it can be dated back as early as the mid-nineteenth century with the creation of comic strip by Rudolphe Töpffer in 1827 and the publication of his seven graphic novels in the subsequent years. The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbucks (1837) was one of the Swiss cartoonist’s graphic novels (and the most famous one) which contains one to six drawn panels with a caption of narration underneath. Nevertheless, Töpffer’s graphic narrative was not read in the U.S. until 1842 when it was eventually translated into English. Comic books—superheroes comics in particular—emerge first in the 1930s and became the dominant genre of the form. The years before World War II saw the glorious days of comic book as it was the dominant medium of youth culture before the advent of television (Costello 3-5). The comic books industry later encountered several setbacks throughout the 1950s and the mid-1990s with economic depression and the invention of television, movies, and video games. Recently, comic books have however

attracted new awareness and interest with successful film adaptations of comic books characters—especially that of the superheroes.2 Today, comic books enjoy a wide readership, ranging from children to adults of both sexes. Whereas comics can be found usually in the form of comic strip in a newspaper, marketing strategy has

2 For the development of my thesis, I have restricted the historical development of comic books only within the region of America. Also, I do not intend to go in depth to explain the historical development of graphic novels as I might spend pages rumbling on it and, worse yet, go sidetrack. For further information, please refer to Matthew J. Costello’s book, Secret Identity Crisis: Comic Books and the

decided to publish comics in a stand-alone storybook. In other words, a graphic novel is actually a comic book with longer story-length. Beverley Crocker suggests that “graphic novel” is a publisher’s term as a mean “to counter the stigma of comic book,” which has been regarded as a low-culture form (3).

Raymond Briggs’s The Snowman (1978) and When the Wind Blows (1982) might be considered as the forerunners of graphic novels through which Briggs experiments with the genres of children’s picture books and comics. Later, with the popular

acceptance of Maus and Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1986-1987), the market for graphic novels has grown rapidly. Despite decades has passed, the craze for graphic novels still remains, heralding the rise of other graphic novels such as Persepolis (2000), The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian (2007), Tales from Outer Suburbia (2008), and Anya’s Ghost (2011).3

Being regarded as a form of popular culture, the importance of graphic novels was trivialized in the past. Many scholars have argued that the graphic novel genre is underutilized, claiming that it carries deep socio-cultural allegory—which offers us an insightful window into the study of cultural change and the impact of this very

alteration has on each social group (including that of Asian Americans). For example, Töpffer’s cartoons present satirical views of the nineteenth century European society. Using Superman as his model, Umberto Eco has argued that the superhero comic is a very appropriate venue for cultural myths of late capitalism. The Walt Disney comic books,4 according to Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, are an agent that helps disseminate the imperialist’s ideology and culture.5 By employing American

3

The graphic novel, Persepolis, is illustrated by Marjane Satrapi and Sherman Alexie is the author of

The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian with Ellen Forney as its illustrator. Tales from Outer Suburbia and Anya’s Ghost are respectively drawn by Shaun Tan and Vera Brosgol.

4 Disney comics have a world-wide reception since 1940. Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (since 1940) and Uncle Scrooge (since 1952) are the two most notable comics.

superheroes comics as an entry point to study the socio-political relationship between U.S. and other countries during the Cold War, the graphic novel, according to Costello, “is highly responsive to cultural trends [and] provides a unique window into American popular culture” as it has been a widely circulative medium during most of its history (5). Spiegelman’s Maus and Satrapi’s Persepolis, in particular, have proven that the graphic novel is a representational mode capable of addressing salient political, social, cultural, and historical issues with an explicit, formal degree of self-awareness (Chute 769). The fact that many literary scholars consider Maus and Persepolis as valuable texts to access various issues such as the Holocaust and ethnic studies has confirmed that, like traditional literary genres, graphic novel is also “a form of expression” (McCloud 173). With the delicate combination of words and, mostly, images, to convey meaning, writers, according to Crocker, “finds that it offers opportunities to explore key issues through the interplay of word and image in an extended text through diverse narrative structures and encourages different points of view” (3). Given the exciting potential of the graphic novel and its literary value in shedding light on human condition, no wonder Crocker claims that graphic novel “is a format that is at last achieving mainstream recognition” (1, my emphasis).

In accordance with this line of thoughts, The Coming Man, American Born Chinese, Shortcomings, and Secret Identities: the Asian American Superhero Anthology are selected because together they can serve as an alternative form to (re)examine Asian American immigrants’ experience, as well as contribute to the politics of representation. Nonetheless, some important questions should be answered first before proceeding to discuss the preceding graphic novels, these questions

include: What are Asian American graphic narratives and what qualify them to be one?

Chilton (Bllomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), 124. As for Ariel Dorfman’s and Armand Mattelart’s argument, see How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (London: IG Editions, 1975).

What can graphic narratives tell us? And, finally, how can it as a genre contribute to the field of Asian American studies?

The Coming Man and Asian American Graphic Narratives

Generally speaking, my definition of Asian American graphic novels is graphic novels that are written and illustrated by American authors of Asian ethnicity.

Particularly, the story of the novel should concern about Asian American experiences and characters. Without which, my thesis will lose a focal point in observing the impact of racial stereotypes has had in the identity formation and subjectivity of these Asian American characters. Under such definition, American Born Chinese, which narrates the story of Jin Wang—a second-generation American-born Chinese—clearly fits the bill of Asian American graphic novels. So are Shortcomings and Secret

Identities with the former recounts the tale of a Japanese American couple whose relationship is at a crossroad, and the latter consists of short stories about superheroes of Asian descents and their life in U.S.

Because these graphic texts involve the negotiation of white hegemony, they not only operate as an experimental and revisionary narrative that serves as a meaningful site for examining the politics of culture, representations, as well as identity of past and present but, more importantly, they also challenge the prescriptive paradigms that sets Anglo-Saxon subject as normative whilst projects the burden of difference onto the body of the ethnic subjects. Despite the fact that it lacks of a storyline like the other graphic novels, The Coming Man is selected here inasmuch as it represents a peculiar kind of narrative in revealing the symbolic violence of racism. As a

collaborative effort by three Asian Americans—Philip P. Choy, Lorraine Dong, and Marlon K. Hom—The Coming Man is a compilation of editorial caricatures about

Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth-century United States through the eyes of the dominant white subject. Whilst most of the caricatures in The Coming Man limn Chinese immigrants as a derogatory race prone to vice and illegalities, the

compilation turns to become a narrative strategy to resist and to question the generic scripts of white hegemonic force.

Rhetoric of Graphic Narratives

When dealing with graphic novels, it is instrumental to notice the three major characteristics of the genre: First of all, since graphic novels are teemed with and primarily use images, it is hence necessary to probe into the essential nature of visual images. Secondly, the graphic novel is categorized as one of the eight industries of mass media which transmitted via the medium of images.6 Finally, it has grown to become a form of popular culture over the years for its massive success and public reception. I will discuss the first feature of the graphic novel in this chapter and resumes to discuss the rest in the next chapter respectively as I intend to employ them to expose the power relationship between the ruling elite and the ethnic minority. For instance, the media representations of “yellow peril,”7 which were prevalent in the U.S. during the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, were promoted by dominant periodicals and newspapers such as Puck, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and Harper’s Weekly to stir up public emotion to resist or even discriminate against Asian laborers. Particularly, the Chinese immigrants were

presented in political caricatures as a debased, clannish, and deceitful race which lurks

6 Mass media can be classified into eight mass media industries: books, newspapers, magazines, recordings, radios, movies, televisions, and the Internet (Biagi 9-10).

7 A large amount of Chinese and Japanese began immigrating to the U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century. Many of these immigrants worked as laborers on the transcontinental railroad. A surge in Asian

immigration in the late nineteenth century gave rise to a fear that referred to as the “yellow peril.” The phrase was commonly used in several newspapers, including The San Francisco Examiner and The

to overtake America from the hand of White folks.

“The methodologies for interpreting the visual language of the comic book,” remarks Costello, “remain relatively underdeveloped” (24). In fact, many tend to recourse to film theories when it comes to the study of the graphic novel as both appear to be visual and sequential art forms. Despite the theoretical discourse of film studies might shed light upon graphic novel studies, the graphic novel, nevertheless, has its unique and exclusive features and junctures that mark its difference from film and even animated cartoons. McCloud observes that “the basic difference is that animation is sequential in time but not spatially juxtaposed as comics are. Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space—the

screen—while each frame of comics must occupy a different space” (7-8). Hillary L. Chute and Marianne DeKoven go on to elaborate McCloud’s observation, claiming that:

The graphic narrative… differs from… film… because it is created from start to finish by a single author, and it releases its reader from the strictures of experiencing a work in time. While seminal feminist criticism has

detailed the problem of the passive female spectator following and merging helplessly with the objectifying gaze of the camera, the reader of graphic narratives is not trapped in the dark space of the cinema. She may be situated in space by means of the machinations of the comics page, but she is not ensnared in time; rather, she must slow down enough to make the connections between image and text and from panel to panel, thus working, at least in part, outside of the mystification of representation that film… produces. (769-770)

both are able to provide visual pleasure to the audience and the reader, respectively, allowing them to obtain massive information in a short glimpse. One basic difference between graphic novel and film is that the graphic novel offers a reading

experience—as in traditional reading—in which the reader manipulates the speed of perception and can linger and look back at will. Another distinction between graphic novel and film is that the graphic novel can accommodate reasonably long passages of narration, while film usually includes only dialogues or conversations between

characters.

Additionally, whereas film directors are limited to the appearances of living actors available for necessary roles, a graphic novel illustrator can draw characters as he desires. Such attribute of the graphic novel, I argue, allows us to approach the problem of representation more effectively because the way in which a graphic novel deals with visibility as meaning is fundamentally transmitted through images and appearances in a graphic narrative. The mass media, as contended by scholars such as Stuart Hall and James Lull, is an influential tool which the dominant group employs to exert its social controlling power. Media representations in this sense are teemed with dominant ideology attempting to consolidate white authority whilst enforcing limitations and restrictions upon ethnic minority groups. Focusing on Asian

American’s images in the graphic novel can provoke us to rethink and reexamine racial representations as media construction or as part of the ruling elite’s complex range of strategies to characterize and pigeonhole Asian American subject.

Since the graphic novel is a composition of written words and massive images, it conveys meaning by employing both words and illustrations. Let us first examine the mechanism of words in graphic novels. According to Costello, there are three types of written words in graphic novels: spoken dialogues; internal monologues; and

narrations given by the editor, writer, or other third party (23). Reading a graphic novel require high levels of engagement to both images and words because the general relation between the two can affect, reinforce, alter, or even undermine the apparent meaning of the visual narrative. There is thus a set of rules—including the stylized renderings and drawings—that the reader needs to pay particular attention to in order to acquire a fundamental understanding towards the visual narrative. The mechanism of image functions somewhat irregularly in conveying meaning (a point I will explain later), when a reader fails to grasp the image, he has to resort to the words to make sense of the images he sees. The words, Roland Barthes notes, anchor the way the image is interpreted (33-40). At times, however, the denotative context of the narrative text is contrasted by the connotation of the visual text. In other words, the image may present a view of the text that differs from that conveyed by the word. Such phenomenon offers the reader a space of contention; this is why it is important to scrutinize the mechanism of image in a graphic novel.

Etymologically, the word image is linked to the root imitari.8 According to the Oxford Latin Dictionary, the Latin word, imitari, literally means to copy after, to imitate, to simulate, or to counterfeit. We, thus, find ourselves confronted with the problem of representation. If we draw a chair, other will know it is a chair we are drawing because of the similarity or the resemblance of the image we draw with the real chair. Differently put, we copy the image of the chair on a piece of paper.

However, a chair is but an inanimate object, its external form takes up almost all of its representation. It is sufficient for one to recognize it is a chair just from the features of the sketches, even for a few simple lines. The external characteristics thus become the essential traits that give meaning to an illustration or an image because as soon as one

sees the external attributes of a drawing, the visual image that is perceived by him is bound up with his empirical knowledge to determine or define what he sees. Let us draw something animate, say, a person. Some may draw a stick figure, which features a circle for the head and five strokes for the character’s torso and limbs; some with excellent drawing skill might draw something even more realistic. In any case, due to our experience, we can immediately tell what the drawing on the paper is. Now, besides the human resemblance, what else can we tell judging from the drawing? Certainly one has no trouble in identifying the sketched character’s gender (male or a female), stature (fat or skinny), and height (tall or short) by judging from the given information. These given information, albeit constitutes by lines, it nevertheless invokes empirical knowledge for the viewer to tell what the drawing represents. However, it requires a deeper knowledge or more information when the inner characteristic of this very character is enquired. Perhaps this time, a skillful artist is needed to complete this task because what is required has surpassed the scope of a few simple lines can manage. Even experts may possibly fail to meet up our

expectations since we do not share the same experience. Invisible ideas such as sense, emotions, spirituality, and philosophy are hard to draw, or, conveyed by drawing. Indeed, one can simply distinguish whether a drawn character is happy or sad, afraid or secure, but, what if I ask for something more sophisticated? Even if the drawer meant to draw it, the viewer may still fail to make sense of the feelings of the

character when being shown the drawing. Hence, some artist might resort to color, or even by drawing something extra, such as landscape at the background, to provide the extra information needed for his viewers to comprehend his intentionality.

Nevertheless, as Roland Barthes has suggested, an image or illustration is polysemous and opens to all kinds of interpretations (37). Since visible traits transmit meanings

and connotations much more directly in comparison with the abstract ideas and concepts, an illustration tends to show the visible as it speaks across the public

domain and because the public shares the same empirical sense. However, images can be counterfeited. How so? Because an image is something that depends so immensely on external traits, simple and minor alterations can change its fundamental essence as well.

FIGURE I.1. A set of facial expressions.

Figure I.1 verifies my point. While the basic framework of circles enable us to identify them as human heads, and most probably of the same character, we also know that each one of them represents different sets of facial emotion as the lines within the circle clearly differ. Hence, it can be concluded that the lines within the circle govern the expressions or generate certain meanings of the character. Still, the images in graphic narratives are much more advanced and sophisticated than of figure I.1; how, then, do we perceive the intended meaning of an image? As mentioned, Barthes has observed that an image is polysemous. Its meaning is indefinite because it does not function as a Saussurian system of language (la langue). There is no verb, nor an obvious “subject,” nor a grammar of tense in an image. “Image,” as Christian Metz posits, “yields to receive a quantity of indefinite information, like statements but unlike words” (43). While the structures of written language and images are entirely different for Metz, how can we keep meaning from proliferating? Without an indicator to anchor the way the image is interpreted, a picture can lead its viewer to misreading.

This is particularly devastating for a visual narrative. Certainly, our empirical sense and knowledge give us the necessary instinct to interpret the sets of facial expression I enumerated above. And, indeed, the use of written words together with the visual image can possibly provide a much more luminous indicator to establish meaning(s) in comparison with sheer image. Such is the case of most graphic novels but, even so, there is still a risk as the meaning presented by the denotative context of the narrative text and the connotations of the visual image might be unparalleled. If the reader has to resort to written words in order to make sense of the image, caricatures would definitely appear to be nonsensical and meaningless as they are mostly depicted in sheer images. Can caricature still convey meaning or, more importantly, a stable narration? Jonathan Hunt asks a similar question, too: “Can a wordless narrative be literary?” To which he answers, “Despite the absence of words, a visual narrative can be evaluated for plot, character, setting, style, and theme” (425). While many scholars have acknowledged the fundamental difference between visual images and written language, I argue that the structure of image has its own systems of language as well; we may even call it a system of image.

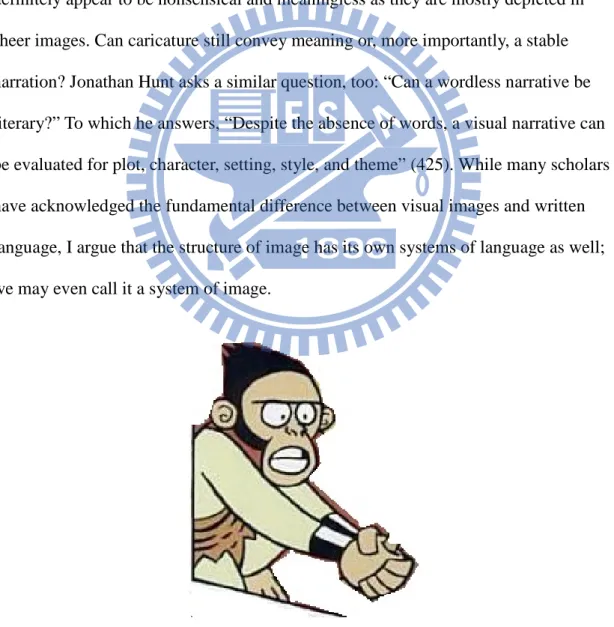

FIGURE I.2. A furious monkey? American Born Chinese. New York: Square Fish, 2006. 17.

According to Saussure, a linguistic sign, due to its arbitrary nature, can never fix or determine its own value without its comparison to other similar signs that stand “outside it” and “in opposition to it” (115). “In language,” Saussure stresses, “there are only differences without positive terms” (120); in other words, the precise meanings of words are relational and negatively comparative. For instance, in the sense of the signifier, tree is what it is because it is not gree or dree; and in the context of the signified, the designation of tree depends upon its negative relation to sapling or shrub. Whereas the Saussurian linguistic model is based on a binary opposition, the unity of the message in an image or picture can be acquired via juxtaposition. The signifying value of one single drawing is arbitrary; hence, it might suffer the

possibility of being opaque because it does not have an indicator to anchor the way it should be interpreted. A viewer will be given more information if a drawing is juxtaposed with another. For example, figure I.2 shows a furious monkey (judging from his facial expression) interlocking his fingers, a viewer may simply fail to decipher more because he is given a very limited perspective.

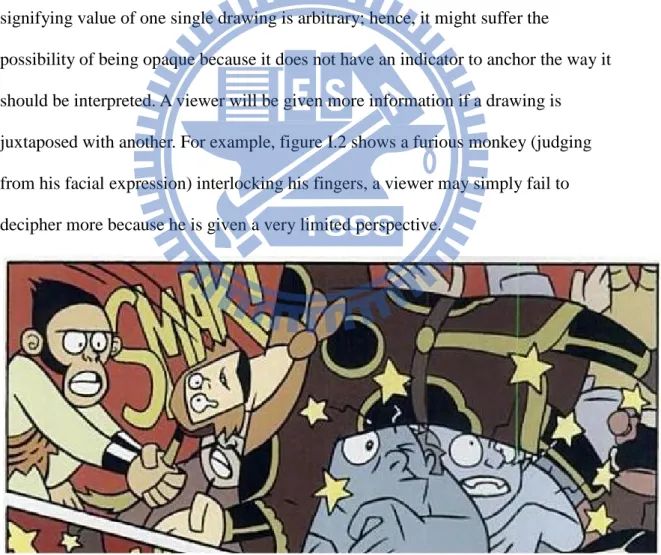

FIGURE I.3. A furious monkey is engaging in a fight. American Born Chinese. New York: Square Fish, 2006. 17.

angry monkey, a picture is immediately being conjured up in the viewer’s mind. By merely looking at the drawing, he might offer a myriad of possible interpretations. A viewer will have a full comprehension (or, comprehend the intention of the artist) about the situation the moment he sees the entire picture. In other words, information, message, and meaning are generated through juxtaposition in an image.

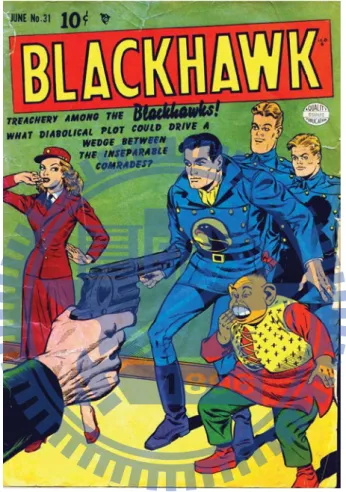

FIGURE I.4. The Blackhawk crews and their sidekick, Chop-Chop. Blackhawk #31, Jun, 1950.

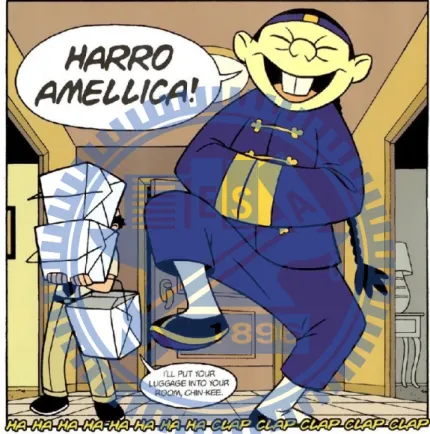

With such notion in mind, let us look at another picture (figure I.4) from DC Comic’s Blackhawk. The yellowish boy at the right bottom corner, whose name is Chop-Chop, demonstrates a strong sense of discordance in juxtaposition with other Caucasian characters in the picture. Chop-Chop’s existence—his petite figure,

comical haircut, and his motley Changshan—seems to be emphasizing his “otherness” in comparison with his charismatic teammates. Likewise, such discordance is

exhibited in Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese as in the case of Danny and Chin-Kee as well (figure I.5). Once again, the viewer finds it hard to identify with Chin-Kee because of his exotic figures—slanted eyes, buck teeth and queue. By presenting the Blackhawk and Danny as the normative characters, a core message is, thus, transmitted via these pictures, that is, the otherness and the exoticism of

Chop-Chop and Chin-Kee.

FIGURE I.5. Chin-Kee makes his appearance in American Born Chinese. American Born Chinese. New York: Square Fish, 2006. 48.

Until now, the approach of juxtaposition is being utilized within a single image; nevertheless, it is equivalently applicable on a larger scale. For example, an editorial caricature of a Chinese immigrant from then nineteenth century can be put in

juxtaposition with a more recent illustration of a Chinese American man. By juxtaposing two entirely distinctive visual genres from different time periods, the outcome of such methodology can be both significant and informative in terms of

their historical, socio-cultural backgrounds as well as the illustrators’ views on the objects in question (a reflection of the public opinion). Juxtaposition in this sense is thus an effective and important way to study the graphic representations and

sociocultural situations of Asian American throughout the ages.

The discussion of how meaning is generated in a picture does not simply end with the concept of juxtaposition. Consider again the two pictures I just enumerated; the mechanism of juxtaposition is made possible due to the vivid contrast between Chop-Chop/Chin-Kee and the Blackhawk/Danny in appearance. Similar to figure I.1 which represents different set facial emotions due to the distinctive lines within the circle, minor alteration on appearance generates different meanings in an image. In addressing to the difference between verbal and visual narratives, McCloud contends: “In the non-pictorial icons, meaning is fixed and absolute. Their appearance

doesn’t affect their meaning because they are invisible ideas. In pictures, however, meaning is fluid and variable according to appearance. They differ from ‘real-life’ appearance to varying degrees.” (28)

McCloud’s argument highlights yet another crucial feature of the image, that is, it is able to fabricate the essence of the object or entity it presents, imposing new meaning or new connotation upon it. As I have contended previously, an object’s appearances control and define most of the meaning it presents. Almost at once, many are able to recognize a character as Asian as long as long as the character is distinctively featured with slanted eyes, buck teeth, and a flat nose without any statement. These visual representations of Asian and Asian American have ingrained so deeply in our empirical knowledge that most people consider it as a matter of course even if they are misleading and untrue. These visual representations, argue Kent A. Ono and Vincent N. Pham, “register on the senses and in the mind, the collective and often

repeated images… become part of memory, both individual and social… Through their repetition and power to educate audiences,” Ono and Pham go a step further to suggest that these deceitful representations “may be reproduced across time

unwittingly” (8). An image, in short, is able to simulate or counterfeit information, replacing or even transcending reality.

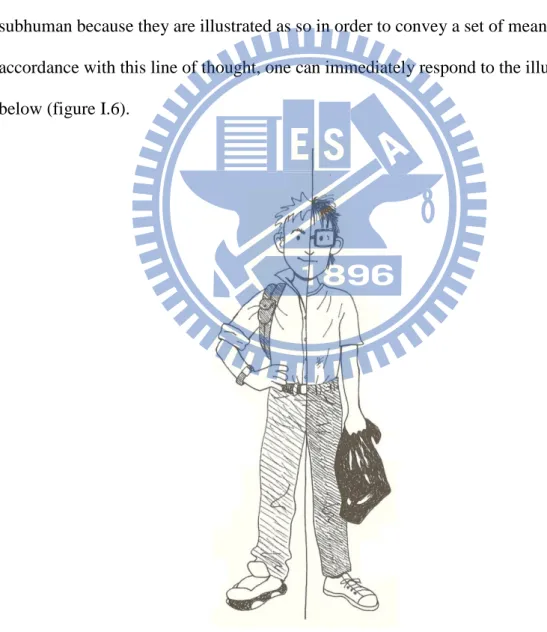

Chop-Chop’s conspicuous miniature stature and Chin-Kee’s bizarre portrayal immediately provokes the reader to associate them with deformity, inferiority, and other negative nuances. Both Chop-Chop and Chin-Kee are condemned to become subhuman because they are illustrated as so in order to convey a set of meanings. In accordance with this line of thought, one can immediately respond to the illustration below (figure I.6).

FIGURE I.6. An edited picture of The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian. The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian . New York: Little, Brown Books for

Young Readers, 2007.

This picture, which I excerpted from The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian, was originally captioned but I edited it for the purpose of demonstrating my point. Surely, one does not need me to point out that the boy in the right has a messy hair and wears a ragged T-shirt, whereas the boy in the left might be richer judging from his shirt, shoes, and wristwatch.

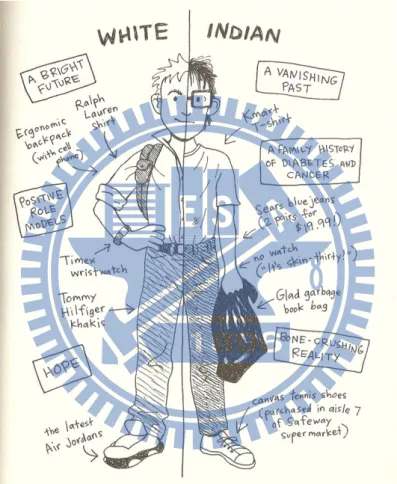

FIGURE I.7. The original illustration. The Absolute True Diary of a Part-time Indian . New York: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2007.

Figure I.7 is the original excerption; compare what you have thought regarding figure I.6 with the given captions. What you thought of figure I.6 must be close, if not exact, to these captions. External traits including skin color, stature, and facial contour not only turn out to be the indicator of the characters’ identities but also who they are

and, internally, as individuals as well.9 The visibility of appearance has, therefore, become a medium through which invisible notions, thoughts, values, and perceptions are conveyed, propagating the ideology of White hegemony at the expense of the ethnic subject. I will go into further detail to discuss this in the next chapter.

What must be remembered that each of these pictures and texts (if any) is a part of a story. Hence, the relationship between one picture and another; one text and another; image and text; must be meditated within the framework of narrative. Only through which we can have a better understanding of the mechanism of graphic novel and the embedded meaning it carries.

The Organization of My Thesis Project

My thesis project consists of three chapters. Since the discussion on graphic novels is relatively new, a literary review regarding the impact of the graphic narrative on the literary field will be provided in the beginning chapter in order to justify, like other literary works, it is a form of expression and a “representational mode capable of addressing complex political and historical issues with an explicit, formal degree of self-awareness” (Chute 769). I will then define “Asian American graphic novels” and the criteria it must meet to qualify as one. Subsequently, I will advance to discuss the “system of image,” including the characteristic of the image; its difference with Saussurian’s la langue; and how meaning is generated and contained in pictures and graphic narratives.

Entitled “Drawing and Containing Anxiety: Ethnic Caricature, Stereotypes, and Anglo-Saxon Purity,” chapter two will take on the challenge of deconstructing racial

9 Indeed, the mechanism of appearance is not limited only for the characters, a change in style, inking, perspective, location in panels, size and type of panels, arrangement of panels on the page, lettering, the use of line, the arrangement of panels on a page, and the presence or absence of a gutter, according to Costello, all has profound influence on the meaning of a narrative (23-24).

stereotypes. Evidently, the issue of racial stereotypes is at the core of American Born Chinese and Secret Identities: The Anthology of Asian American Superhero as both graphic narratives are reek with the usage of easily identified racist images of Asians and Asian Americans. Attaching humor to Chin-Kee’s character and behavior, Gene Luen Yang juggles with the common misconceptions of Chinese and Chinese Americans that proliferate in both historical and contemporary discourses in the United States, including those rooted in American immigration history from the nineteenth century and more recent examples such as the model minority. Jeff Yang and his co-authors in Secret Identities, on the other hand, though somewhat

inconsistent or cohesive, aim to exorcise old racial myths by empowering the Asian community with their creation of various Asian American superheroes. As acclaimed comics writer and artist Will Eisner has noted, “… the stereotype is a fact of life in the comics medium. It is an accursed necessity—a tool of communication that is an inescapable ingredient in most cartoons” (11).

That being said, the approaches of ethnic stereotypes in a graphic novel format is worth exploring inasmuch as, historically, “the mediums of cartoons, comics, and comedy have been used to make fun of Asian Americans and to perpetuate stereotypes of corporeal, cultural, and social differences” (Cong-Hyugen 86). In studying the phylogeny of the comics-genre, Lan Dong writes:

Emerging as a “distinct entertainment medium” in the 1930s, comic books continued to recycle racist stereotypes and to incorporate political

propaganda, including strikingly racist portraits of Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese in comic books published during World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars. When the graphic novel emerged as a popular form in the 1970s, its creators borrowed many conventions from serial comics.

(242-243)

While Dong’s discovery points to the evident connection between graphic novels and editorial caricatures,10 Yang further gestures toward this fact by having Danny attend Oliphant High School (109), an allusion to editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant, who was occasionally accused for his racist caricatures, especially of Asian Americans. With the likes of Dong, Cong-Hyugen, and Hong all calling attention to the importance of editorial cartoons in the discussion of racial stereotypes, this article hence focuses on ethnic caricatures in the development of racial stereotypes. Here, it is worth

mentioning that there are three significant stages that contributed to the creation of ethnic stereotypes in the United States: (1) the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War and the California Gold Rush; (2) the Cold War which spanned from the 1950s to the 1960s; and (3) the transnational stage. Chapter two will mainly focus on the first stage because Asians were first recruited as miners and railroad workers. In particular, the stage has spawned various Asian stereotypes and some of which has remained influential even until today.

Beginning with a brief introduction of Henry B. Wonham’s “ethnic caricature,” I explore the popularity of this graphic creation in American newspapers and

periodicals during the nation’s imperial venture in the nineteenth century. Ostensibly functioning as ethnographic illustrations of the immigrants, caricatures of this variety magnified the racial others’ radical differences from the white race. By exaggerating their innate cultural and ethnic discrepancy, it declared the immigrants unfit for American citizenship whilst reminded white Americans of the immigrants’ menacing potential for sabotaging the necessary (ethnic and cultural) homogeneity of a country. With the national fantasy of racial purity under duress as a result of the influx of

10

Editorial or political caricature is a combination of social critique that usually relates to current events or personalities with sequential artistic scenes (Petersen 32).

immigrants en masse, I argue that the nineteenth-century American was

overshadowed by a collective anxiety that equivalent to that of the Freudian castration anxiety.

Such analysis further paves way for another psychoanalytic notion—that is, reading ethnic stereotype as an analogue of fetishism. Operating as a mode of defense to sustain the subject’s original fantasy, fetishism offers a mediative effect between the subject and the disturbing other through the substitutions of condensation and displacement. By reducing and essentializing all the “knowledge” one needs to understand of the (racial) other as a whole in one single image, ethnic stereotypes become the “regime of truth” (or a de facto erudition) of the other whilst they are in effect “individualized” with unilateral assumptions—what stereotypes represent are not the beliefs based upon reality but ideas which reflect the distribution of power in society, if you will, an expression of ideology (Hall 259-261).

The deployment of stereotypes emphasizes the visible necessity in the exercise of power as a clearly visible part of the other—i.e. its body and skin—becomes the fetish object. One of the most critical narratives from Secret Identities reveals how the epidermal schema of body/skin becomes a “discursive site through which… [the] ‘racialized knowledge’ [is] produced and circulated” (Hall 244). But the fetishistic action can never definitely eradicate the realization of difference due to the

ambivalent nature of the self and the other, according to Jacques Lacan in his

discussion of the mirror stage. Ergo, the relief from anxiety is only short-lived before the fetishistic act must be carried out compulsively and repetitiously again. It is the element of irresolvability that gives a stereotype its currency—its ability to reproduce across mediums and time. Its endurance in popular culure—in contemporary comics culture, for instance—has indicated its lasting imprint in public memory; not to

mention its function as a sign with meaning(s).11

The third chapter of my thesis explores how racism construes Asian people as the perpetual foreigners whilst examines the impact of racism on the subjectivity and identity of Asian American. Focusing on American Born Chinese and Shortcomings, I argue that racism not only plays a dominant role in delineating the national space of the United States but, more importantly, it also has a profound influence on the

identities and subjectivities of the main characters. Structurally identical to Jin Wang’s coming-of-age story, Yang’s reimagining of the Monkey King’s legend not only allegorizes the predicament of the Asian American community but also serves as a social critique towards the establishing symbolic violence of racism. In Yang’s version of the Monkey King myth, the symbolic significance of the shoes is accentuated inasmuch as the footwear is the key signifier in the formation of identities and in delineating the subjective space of the immortals, according to the doorman: access is only granted to those with shoes whilst entry is denied to those without them.

Likewise, the same is clearly true of the United States as the nation’s legislation had legally prohibited the ethnic others from naturalization and immigration as a means not only to ensure the racial homogeneity of the nation and to safeguard the national space, thereby turning ethnic and cultural characteristics as the requisite of national legitimacy. The historical construction of people of Asian heritage as an “object of national prohibition” thus renders them as the perpetual figure of xenos.

The nation’s form of citizenship and civil rights law were fundamentally reformed following a shift in the U.S.’s mode of capital to transnational capitalism during the 1960s. With America’s agenda to maintain its “positional superiority” on

11 I have suggested previously in this chapter that information and meaning in a picture are encrypted visually. Deciphering these visual encryptions requires a reader to take extra heed of a (or more) character’s facial contour, skin color, behavioral attributes, and so forth inasmuch as meaning is encoded within these visible identifiers—they inform the readers about what the illustrator intends to convey.

the global economic market, former structural barriers such as the restrictive laws in citizenship were renounced, hence catalyzing the categorical birth of “Asian

American” (Li 6-8). However, despite the state’s commitment to formal equality to all races, Asian American citizen status remains marginalized on the cultural front where white cultural force still dominates. Due to the ambivalence status of the Asian subject, David Leiwei Li hence argues that “Asian American has been turned into an

‘abject’”—as he is neither the total alien nor the full-fledged citizen (6). With identity continues to be made explicit through ethnic distinctions of white/non-white, Jin Wang’s and Ben Tanaka’s desire to fit in is thus severely impeded. Yet, their aspiration is in effect a socialized process to claim subjectivity; but their failure to do so not only renders the process incomplete but, worse yet, put their subjectivity in peril. Here, their threatened subjectivity is equivalent to the boy’s castration anxiety depicted by Jacques Lacan in his psychoanalytic discourse of the Oedipal complex (Dor 111-19). Whereas the boy’s castration anxiety or Oedipal aspiration can be ephemerally alleviated through the achievement of the paternal metaphor; the Asian American subject, on the other hand, is excluded by the Law,12 and hence his Oedipal aspiration can never be fulfilled. Being put permanently in the state of castration, the Asian subject thus experiences what David Eng terms as a kind of “racial castration” (345-52).

As the topics of masculinity and manhood are central to both American Born Chinese and Shortcomings, Yang and Tomine graphically suggest that Asian

Americans are symbolically emasculated. To list a few, Jin’s aspiration to date Amelia Harris is violently put to an end by Greg and Ben’s morbid infatuation towards white women has driven his girlfriend—Miko Hayashi—away from him. Regrettably,

12 Briefly put, the Law is synonymous to Lacan’s notion of the-Name-of-the-Father, the laws and restrictions that regulates the subject’s desire and the rules of communication. I will further elaborate on the Lacanian Oedipal complex as well as his overall psychoanalytic model in Chapter III.

because of space constraint my thesis can only focus on the issue of Asian American masculinity and cannot go further into the discussion of Asian American women. Perhaps such limitation can be compensated in future research.

Confronting with social, cultural, and emotional rejections, Jin and Ben are both forced to develop coping mechanisms to manage their desires and fears as Asian American men. Whilst Ben attempts to cut lose his connection to his racial heritage, Jin otherwise fabricates a different person for himself—a Caucasian teenager named Danny. However, these coping mechanisms are not unproblematic as we see Ben is tormented with self-hatred and Danny is constantly haunted by the intrusion of his Chinese cousin, Chin-Kee, leaving their identity and subjectivity unresolved. Towards the end of Chapter 3, I contend that the Asian subject is torn between his ancestral heritage and his desire for assimilation, hence in need of a new perspective in reclaiming Asian American subjectivity.

Concluding Remarks

Graphic novels should be taken seriously aesthetically as well as politically. Whereas most graphic novels in the past have limited representation of minority groups, by the same token, the negative mass media portrayals and their damaging impact can be subverted and resisted with members of social minority groups

establishing their own minority media; in this case, creating their own graphic novels. The establishment of individual media has been not only to fight against unjust treatment and attain social as well as political parity with the dominant groups in society; but also to achieve a sense of empowerment and cultural awareness for the minority groups. The genre of the graphic novel, as argued by McCloud, Lavin, Hunt, Christensen, and Boatright, not only has provided countless opportunities but has also

initiated a new ground of expression and meaning, even Spiegelman asserts that, “graphic narratives, on the whole, have the potential to be powerful precisely because they intervene against a culture of invisibility by taking the risk of representation” (Chute 772). Following this line of thought, I see the publication of American Born Chinese, Shortcomings, and Secret Identities: the Asian American Superhero Anthology as an act of self-empowerment for Asian American as these four graphic novels might have provided them with the opportunity of self-representation. As such, Asian Americans are able to reclaim their subjectivity in visual media and challenge the ideology of White hegemony, which had long deprived of their autonomy to construct their own identity and self-representation. By studying Asian American graphic novels, the power relationship between social groups will be uncovered and questioned. Such inquiry will be made more effectively by scrutinizing the

employment of images and narrative in graphic novels as they highlight the artificial nature of social groups, pop culture, and even racial stereotypes. The graphic novel is, thus, a subversive tool of cultural criticism and a counter-hegemonic force that

empowers the minority groups to rise against the dominant elite and reclaim its subjectivity in the field of visual representation.

Chapter II

Drawing and Containing Anxiety:

Ethnic Caricatures, Stereotypes, and Anglo-Saxon Purity

This chapter enumerates some of the earliest ethnic caricatures from the more proletarian periodicals—White and Bauer, Life, and Judge, for example—to uncover ethnic stereotypes as a defensive mechanism of narcissism for an Anglo-Saxon subject in a time when immigration was profuse and as a primary mode to justify the white subject’s dominance over the ethnic others.

Here I would like to acknowledge my indebtedness to Homi K. Bhaba’s criticial essay, “The Other Question… the Stereotype and Colonial Discourse” (1983). Ethnic stereotypes are employed to rationalize oppression—oppression that fist materialized as a result of colonialism and colonial expansion—although Bhabha’s writing seems to focus primarily on the colonial relations. Asian Americans’ marginal status and invisibility in popular media have exemplified the continuation of colonial rule and colonial relations. By examining caricatures and graphic narratives, my essay shows that ethnic stereotypes actually reveal nothing about the other; per contra, they tell us a lot about the white people since they are used to reassure the reader of the safety of their opinions and prejudices.

Anthologizing cartoons and illustrations mostly from the more plebeian periodicals (such as The Wasp, Puck, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly), Coming Man (1995) is a compilation edited by Philip P. Choy et al about Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth-century United States. Irrespective of its aesthetic value, Choy’s collection is highlighted by its potential to expose how racism is unfolded in graphic images, as modes of stereotypical discourse and of

identification, within the unique political and racial climates of America. In spite of the miscellaneous styles in drawing, most graphic caricatures

collected in Coming Man have visualized Chinese people generally alike,

characterizing them often as one with greenish yellow skin, squint eyes, bucktooth, and a queue hairstyle. In addition to their graphic similitude, they are visually delineated as a degenerated race prone to violence, anarchy, corruption, vice, and illegalities—such as prostitution, gambling, and opium smoking. Disturbing as they are, such ethnographic illustrations of (racial) otherness were surprisingly popular within the public domain of nineteenth-century United States.

Distinguished by its significant ethnic dimension, Henry B. Wonham addresses caricatured images of this variety as ethnic caricatures. Graphic caricatures of this sort, as exemplified by Choy’s Coming Man, functioned to highlight the differences of the other and were undergirded by racial stereotypes.13 The almost ethnographic mode of illustration—in physical appearance, in the foods, religion, and society of the people in question—often condemned the other as objectionable with dehumanized and dehumanizing associations; but, most importantly, Wonham sees the images on racial and cultural differences as a “graphic assault” on “groups perceived to be lacking in [the] essential components of American citizenship” (24). Whilst the “values of honest work, patriotism, common sense, and masculine authority” can be equivocal and abstract, American political identity was otherwise explicitly articulated in many of the ethnic caricatures. The evident lack of “American” qualities among non-white immigrants clearly indicated that they were unworthy of a citizen status, but, more specifically, it also connoted that American citizenship was racially exclusive to white men.

13 Stereotypes are often used as part of the language in graphic storytelling. According to Will Eisner, in comics there is little time or space “to develop a character. The image or caricature must [thus] settle the matter instantly” (12). Eisner’s description has further indicated that stereotypes are representations of idealized character types that are not based on observation but on previous representations. Over time these ethnic stereotypes tend to become widely accepted standards of reference. Saturated with stereotypes, ethnic caricatures have functioned to deliver disgraceful racist images to the masses throughout history.

The Fear of Dispossession

If ethnic caricatures represent an assertion of Anglo-Saxon subjectification, such a racial prerogative must have been regarded as somehow threatening, to begin with. In his discussion of the U.S. citizenship, David Leiwei Li believes that the racial threat posed by the others must be understood in terms of their impact on the concept of nation (1-4). Whilst the unity of a nation was supposedly hinged on its racial and cultural homogeneity, America’s imperial venture during the nineteenth century inevitably “[entailed] the unwelcome elements of difference” in its process of absorbing diverse lands and labor (3), hence risking to disrupt the nation’s

homogeneity.14 Foreigners were brought into the nation whilst the U.S. exerted and expanded its economic, military, and cultural influence worldwide. In this context, foreigners were identified as a threat to the (idea of) nation as well as its ingredients of citizenry. Apart from disrupting the necessary homogeneity, they also “threatened to adulterate the national fantasy of Anglo-Saxon purity,” thereby giving rise to a collective anxiety (1, my emphasis).

Wonham likewise perceives a growing tension within the nineteenth-century U.S. society. Emphatically describing the collective anxiety as a “sense of dispossession,” he writes:

…white middle-class anxieties were running unusually high at the close of the nineteenth century. As affluent Americans flocked to sanatoriums and medical resorts to express their sense of dispossession in nervous suffering, middle-class urban whites turned to the more affordable pages of Harper’s Weekly or Puck for a different sort of medicine, one designed to codify

social distinctions in an atmosphere of debilitating uncertainty. (25)

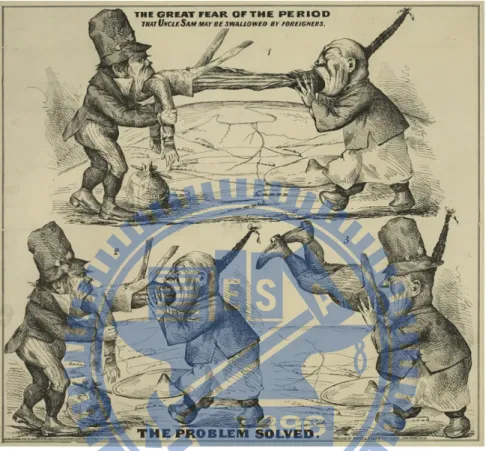

Interestingly, the thematic inspiration of many ethnic caricatures evinced a discursive consistency to Wonham’s observation. Some collection of Choy’s, for instance, vividly expresses the fear of “dispossession.”15

FIGURE II.1. The Great Fear of the Period that Uncle Sam may be swallowed by Foreigners: The Problem Solved. San Fransico: White and Bauer, between 1860 and 1869.

A representative lithograph from the 1860s explicitly visualizes such fervent anxiety with its unnerving caption and appalling illustration (figure II.1). Uncle Sam being devoured by an Irish peasant and a “Chinaman” is “the great fear of the period,” as the first scene depicts that foreigners will gluttonously consume the history,

heritage, and culture of Anglo-Saxon America represented by Uncle Sam. The cartoon further reveals that the Chinese is the worse of the two enemies as he eventually

swallows his Irish counterpart, too. Whilst traces of Irish remain observable—the traditional Irish hat is now worn by the irrepressible “Heathen Chinee,” indicating the preservation of a part of the Irish culture—there is nevertheless no evidence left of Uncle Sam, thus hinting at the massive in-flow of immigrants will result in the complete dispossession of Anglo-Saxon America.

With Asian immigrants swarming into America as a result of the mining boom during the California Gold Rush and the subsequent building of the transcontinental railroad system (Yin 12), the fear escalated and contributed to a height of

anti-Sinicism.16 The creation of “yellow peril” (or sometimes yellow terror),17 a widely used expression in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth

century,18 was driven exactly by this impulse—the fear of dispossession. According to Kent A. Ono and Vincent N. Pham, the term generally refers to the irrational fear that East Asian societies would “take over, invade, or otherwise negatively Asianize the US nation and its society and culture” (25). Unsurprisingly, this racialized discourse was ubiquitous in contemporary popular culture as many addressed the issue through a number of topics—based upon my observation on the

nineteenth-century ethnic caricatures—among them, the perceived competition with the white labor force from Asian workers; the supposed moral degeneracy of Asian people; the possible military invasions from Asia; and fears of potential genetic mixing (i.e. miscegenation) of Anglo-Saxons with Asians.

16 A massive migration to California from all over the world—including China—took place precipitately as soon as the discovery of gold at John Sutter’s sawmill on January 24, 1848. 17 The term was reportedly coined by King of Prussia—Kaiser Wilhelm II—in referring to Japan’s sudden rise as a military and industrial force in the late nineteenth century; it took on a more general meaning embracing the whole of Asia. Gary Okihiro and Gina Marchetti otherwise suggest the notion may date back centuries earlier as Okihiro sees yellow peril as a way of thinking about the Persians by the Greek during the fifth century BC; whereas Marchetti thinks of the term as a reference to the medieval fears of the Mongolian invasion of Europe (Ono 25).

18 Kent A. Ono and Vincent N. Pham otherwise argue that the yellow peril is discursively entrenched and remains influential in the media representations of Asians and Asian Americans until today. For more information, read Ono’s and Pham’s Asian Americans and the Media (2009).

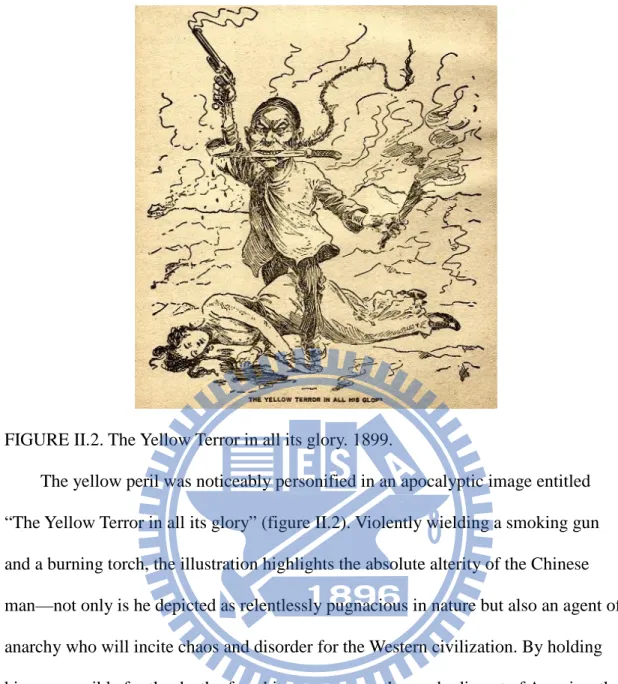

FIGURE II.2. The Yellow Terror in all its glory. 1899.

The yellow peril was noticeably personified in an apocalyptic image entitled “The Yellow Terror in all its glory” (figure II.2). Violently wielding a smoking gun and a burning torch, the illustration highlights the absolute alterity of the Chinese man—not only is he depicted as relentlessly pugnacious in nature but also an agent of anarchy who will incite chaos and disorder for the Western civilization. By holding him responsible for the death of a white women, another embodiment of America, the lithograph further connotes the Chinese is a mortal threat to the nation, as represented by the body lying on the ground. With blood streaming out of her lips, the gruesome scene cautions the public that the U.S. would share the lady’s ghastly fate should the Chinese flock the nation.

The graphic representations of Uncle Sam and the white woman—notably their ethnicities—further articulate an underlying Anglo-Saxon selfhood.19 As a common national personification of the U.S. in editorial cartoons, Uncle Sam’s symbolic