以英文為外語學習者口語中之規避語初探

An Exploratory Study on Hedging Expressions in EFL Learner’s

Spoken Discourse

李美麟 國立政治大學英國語文學系講師摘

要

規避語之研究,向來偏重於探討第一語言中男女性使用之差異;或探討 以英語為外語者在學術寫作中有關規避語之使用。少有研究討論其在外語(尤 其是口語)中的使用情形。本研究之目的,經由檢視大學生之英語口語語料, 探討規避語之運用。受測者為北部某大學三十三位大一學生,其中女性二十 二位,男性十一位,蒐集到約 150 分鐘的口語語料,經由語料謄寫與分析, 比對出以英語為母語者及以英語為外語者的使用異同。最後,本文根據研究 結果,提出關於教學及未來研究之建議。 關鍵詞:規避語、英文為外語、口語語料Mei-lin Lee, Lecturer, Department of English, National Chengchi University

Abstract

Previous researches on hedges have been primarily conducted to investigate how hedging expressions are used in English written discourse, especially in the field of ESP. However, few studies have been made to examine how hedges are used in EFL learner’s oral communication. The purpose of this study is to investigate how EFL college students in Taiwan use hedging expressions in the spoken discourse. The subjects are 33 freshman students at a college in northern Taiwan. A speech sample of 150-minute audio-recording of EFL students’ group discussion is transcribed and analyzed. Totally, 667 hedges are identified from the spoken corpus and then classified according to the taxonomy from Salager-Meyer (1994). The use of hedges between native speakers of English and EFL learners are compared and contrasted. Conclusions and pedagogical implications are then drawn from the findings.

I. Introduction

Lakoff (1972), in his pioneering study, refers to hedges as “words or phrases whose job is to make things more or less fuzzy” (p.462). Hedges serve various functions. They may serve as one type of politeness strategies (Crompton, 1997; Grundy, 1995; Mey, 1993; Salager-Meyer, 2000). In our everyday language use, precision in bald statements, which needs to be done appropriately only in certain situations, is usually not preferred. Instead, imprecision or uncertainty of utterances is even more appropriate than bald statements (Chen, 2007; Lakoff, 1972; Lewin, 2005; Salager-Meyer 2000; Grundy, 1995; Stubbs, 1986, 1996). Lakoff (1972) points out that natural language sentences are very often neither true nor false, but rather true to a certain extent and false to a certain extent, true in certain respects and false in other. Grundy (1995) concludes that hedges serve as “a comment on the extent to which the speaker is abiding by the rules for” (1995: 42).

Hedges are rhetorical devices to show speaker’s sensitivity to other’s feeling (Lewin, 2005; Salager-Meyer, 2000). Skelton (1988) argues that hedging makes language more flexible and the world more refined:

Without hedging, the world is purely propositional, a rigid place where things either are the case or not. With a hedging system, language is rendered more flexible and the world more subtle. Indeed, it is impossible to avoid hedging, yet describe or discuss the world (p.38).

The expressions of such hedged utterances-vague, indirect, or unclear -- are pervasive in all uses of languages (Biq, 1990; Chen, 2007; Grundy, 1995; Salager-Meyer, 2000; Skelton, 1988; Stubbs, 1996). In sum, hedging is a salient feature in our language use.

An L2 learner can sound rude or abrupt because

of a limited proficiency or a lack of awareness of such rhetorical device. Although there have been abundant studies on hedges ever since Lakoff (1972), few studies are conducted to examine how speakers use hedging expressions in an L2 context, with a particular focus on the spoken discourse. Previous studies on hedging can be classified into two major categories: (1) studies in L1 sociolinguistics focusing on how hedges are used by native speakers of English, with a particular focus on gender difference; and (2) studies focusing mainly on L2 written discourse, specifically in English for Specific Purpose (such as medical English, scientific English) or EAP (English for academic purpose) (Hyland 1994, 2006; Lau, 1999). The use of hedges in spoken discourse by non-native speakers of English has been overlooked. The functions that hedging expressions serve in English are not well understood by EFL students as well as teachers. Therefore, Stubbs (1986: 22) stresses the significance of hedging in EFL teaching:

I have also discussed more general aspects of the sociolinguistic competence which is involved in expressing polite, tentative, tactful statements... These aspects of language are a notorious problem for foreign learners. For example, it is notoriously difficult to translate modal particles from one language to another. And it is well known that speakers of English as a foreign language can sound rude, brusque, or tactless to native speakers if they make mistakes in this area. One problem is that their mistakes are not recognized as linguistic mistakes at all, but as social ineptitude.

With a view of the significance of hedging in EFL learning, teaching L2 learners to appropriately use hedges in communication seems to be important for language teachers. This study aims to provide a preliminary account of how intermediate EFL

students in Taiwan employ hedging devices in their spoken discourse, with a focus on examining the frequency and common types of hedging expressions. Also, this study aims to provide pedagogical implications for language teachers or EFL material writers, who need to design activities or prepare teaching materials to help students generate output as close as possible to natural conversation.

II. Literature Review

Hedges and Gender

Hedges are often regarded as a characteristic of women’s language. Ever since Lakoff (1975) included hedges in her pioneering work on women’s language, these linguistic forms are often associated with stereotypical femininity. This view seems to result from the assumption that hedges are used primarily to express doubt or uncertainty (Coates, 1996, 1997b; Freeman & McElhinny, 1996).

Coates (1997b: 249) reports that hedges perform several functions simultaneously. She investigates how females adopt hedges as politeness strategies, which are particularly important “in the maintenance of friendship.” Hedges are the expressions of doubt and the devices of “avoiding playing the expert” (1996:160). She reports that females are likely to use hedges to show their sensitivity to other’s feelings and to establish a collaborative floor. In brief, females use hedges “to take account of the complex needs of social beings” (1996:172).

Previous studies find that hedges are used more frequently by women than men (Coates, 1988, 1996; Holmes, 1984 cited in Freeman & McElhinny; Tannen, 1986, 1994). However, Holmes (1986) finds that men and women use the hedge “you know” at approximately the same rate to express appeals for confirmation and mutual knowledge between interlocutors. In a more recent study, Coates (2003) reports that one of the male subjects used a very high frequency of hedging tokens (7 tokens of hedges out

of 5 lines) in his narrative– in which the male subject constructs his identity in a self-disclosure in an all-male context. It seems that more recent studies on hedges show contradictory findings to those of previous studies. Therefore, more studies based on a larger corpus are called for to investigate the use of hedges with respect to gender.

Hedges and ESP/EAP

Hedging devices are a particularly significant characteristic of academic writing, in which an objective and impersonal style is required. Hedges thus allow writers to express their uncertainty or tentativeness in order to avoid personal accountability for statements. Previous studies have documented the use of hedges in academic writing or in scientific literature. Prince et al. (1982) examine different types of hedges from a corpus of physician-physician discourse at an intensive-care unit. The result shows that the most salient feature of the corpus is “the number and frequency of hedges” (p.84).

Hyland (1996) investigates how hedging expressions in science research articles are employed, based on a contextual analysis of 26 articles in molecular biology. He proposes a pragmatic framework to account for the use of hedges in scientific texts. Salager-Meyer (1994) finds that the discussion and comment sections of medical journal articles are the most heavily hedged sections, from a corpus of 15 articles from five leading medical journals. The study indicates that the most frequently used hedging devices are shields, approximators, and compound hedges, which account for over 90% of the total number of hedges used in the sample. She concludes that hedging is a necessary and vitally important skill in academic writing.

Although the use of hedging devices allows a writer’s claims to be made with proper caution and modesty (Hyland 1994; Lewin, 2005), studies also

suggest that such kind of expressions need to be used judiciously. Some studies indicate that English speakers often consider the writing of NNSs “vague, and insufficiently explicitly if it does not follow the relatively rigid norms of essay writing” (Hinkel, 1997:362). Therefore, understanding how to appropriately use hedges to sound impersonal or objective in academic/ scientific writing is important for L2 writers. In brief, researches into hedges primarily focus on ESP or EAP writing, with little attention paid to L2 spoken discourse.

Hedges and L2 Learning/Teaching

Previous studies have called for the need of explicit instructions of hedges or formulaic expressions. Hyland (1994) suggests that pedagogic writing materials be in need of revision to incorporate more coverage of hedging devices for students to comply with “the sociolinguistic rules of English speaking scientific discourse communities” (p.252). Proposing that EFL learners should be exposed to hedging devices from the earliest stages of acquisition process, Hyland (1994, 1998, 2004) therefore urge textbook writers and materials developers to incorporate hedges into the textbooks even for introductory levels.

Stubbs (1986) also points out the importance of hedging in foreign language learning as well as teaching. He finds that EFL learners sometimes can sound rude or impolite to native speakers because they do not know or have not acquired how to appropriately use hedging tokens. Therefore, he calls the need for explicit instruction in L2 teaching syllabus and teaching material.

Nikula (1996) reports the correlation between the use of such hedges or hesitation markers to L2 learners’ proficiency level. Her study finds that EFL learners produced a much narrower range of fixed phrases or fillers. In her study, even advanced learners produce a much narrower range of

“spoken-like expressions” than native speakers. Hasselgren (1998), Fukuya & Martinez-Flor (2008), and Wood (2009) all call for explicit instructions or focused instruction of such hedging expressions to improve L2 learner’s fluency. These studies support that the use of hedging expressions is important in L2 speaking performance.

Learning how to use such politeness devices is of particular importance to college students in Taiwan, who have already mastered enough grammatical knowledge yet lack the skill or training in properly expressing their opinions with hedging expressions to show politeness or their sensitivity to other’s feeling.

III. Methodology

Research Questions

This study investigates the following research questions: (1) Do EFL learners employ any hedges in their oral communication? What type of hedges do they use? (2) Do L2 learners use these hedges in a similar way that L1 speakers do?

Subjects

The subjects are 33 freshman students, consisting of 9 groups, at the age of 19-20, enrolled in a College English class at a university in northern part of Taiwan. Coming from 5 departments in the College of Commerce, eleven of the subjects are male and twenty-two females. They are asked to discuss topics related to their everyday life in groups. The subjects are chosen because freshman students, after at least six-year’s studying in English, are assumed to have a fair command of oral proficiency and a functional, though limited, repertoire of conversational skills. They could fairly express themselves and are able to communicate with each other in English.

With a casual setting and familiar topics and interlocutors, the speech sample collected is believed to be able to represent student’s proficiency. The

relationship among participants is intimate and friendly since students choose their group members on their own. The solidarity among group members is expected to be fairly high, as they have to finish the discussion task collaboratively to get a score. With a view to the same age and the same educational background, they could be considered as a rather homogenous speech community.

Data Collection

The spoken data is collected from nine audiotapes recording students’ spoken discourse in the group discussion. Students are asked to record the process of their discussion without any interruption. The total length of all the tapes is approximately 150 minutes. In order to motivate students, they are told that their performance in the group discussion would be graded as part of their total semester score. The topics of discussion are the same for everyone. After their discussion, the spoken data is transcribed, coded, and classified according to the taxonomy proposed in the next section.

Classification of hedges

The hedges identified in the spoken data are thus classified according to the four categories. The number of hedges per category is computed as a percentage of the total number of hedges identified in the spoken corpus.

Since the main concern of this study is to examine the frequent types of hedges used by EFL students, the length of pause (or “thinking time”), stress and intonation, and interruptions are not counted in this study.

The classification of hedges is mainly based on Salager-Meyer’s (1994) framework.

1. Shields: modal verbs expressing possibility (can,

will, must); semi-auxiliaries (to appear, to seem);

probability adverbs (probably, likely) and their derivative adjectives; epistemic verbs (to suggest). 2. Approximators: stereotyped “adaptors” and

“rounders” (see Prince et al. 1982) of quantity,

degree, and frequency (for instance, roughly,

somewhat, approximately)

3. Expressions of the speaker’s personal doubt and direct involvement (I think, to our knowledge). 4. Emotionally charged intensifiers: comment words

used to project the speaker’s reactions (extremely

difficult, particularly encouraging).

IV. Results and Discussion

Totally, 667 hedges are identified in the 150-minute corpus. Female speakers (n= 22) used 467 hedges out of the total 667 hedges (70%) while male speakers (n = 11) employed 200 hedges (30%).

The result shows that quite a large number of hedges (667) are used in EFL learners’ spoken discourse. Averagely, every subject in this study use 20 hedges in the spoken discourse. Per minute, 4.76 hedges are used in the corpus. The frequency of occurrence of hedging is surprisingly high. However, only limited types of hedges are adopted by EFL students. As we can see in the following sections, student’s use of hedging devices is mainly restricted to two types of hedges, that is, shields (especially

modals) and expressions of personal involvement,

which account for over 90% of the total number of hedges identified in the sample.

Table 1 lists the four types of hedges identified in the data, with the total number and the frequency of occurrence of each type of hedges. The two most frequently used hedging devices, shields (with a frequency of occurrence of 59.8%) and expressions

of personal involvement (38.5%) account for more

than 98% of all the hedges in the corpus. The other two types of hedges, approximators and emotionally

charged intensifiers, only constitute 1.7% of all the

Table 1: Types of Hedges in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse

Types of hedges Frequency Shields 399 59.8% Modals 351 52.6% Probability adverbs 46 6.9% Semi-Auxiliaries 2 0.3% Approximators 7 1.1% Expressions of personal involvement 257 38.5% Emotionally charged intensifiers 4 0.6% Total 667 100 %

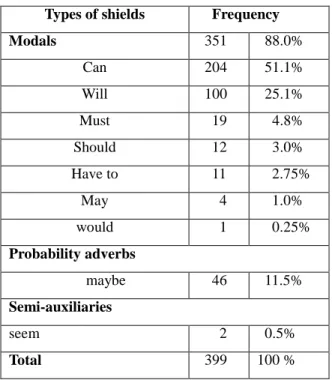

Table 2: Shields in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse Types of shields Frequency Modals 351 88.0% Can 204 51.1% Will 100 25.1% Must 19 4.8% Should 12 3.0% Have to 11 2.75% May 4 1.0% would 1 0.25% Probability adverbs maybe 46 11.5% Semi-auxiliaries seem 2 0.5% Total 399 100 % Shields: Modals

Table 2 shows that of all the types of shields, in which modals constitute an essential part, with a percentage of 88 (351 items from a total of 399 shields). Among all the modals, “can” is the most frequent used one, with a total number of 204 and a percentage of 51.1 in all the shields in the sample. “Will” occurs far less frequently than “can,” with a percentage of 25.1. It is interesting to note that “can”

and “will” are used over 75% of the total shields, while other modals such as “must”, “should”, or

“may” only occur less than 12%. “Can” and “will”

are the most frequent hedges used by the subjects probably because EFL learners acquire the two modals (“can” and “will”) firstly in the process of language acquisition. Consequently, they are most capable of utilizing these two items.

With respect to the use of modals, the L2 subjects in this current study show a divergence from L1 speakers. Modals are used, besides expressing probability, as a kind of pause-filler or hesitation discourse marker since modals are usually followed or preceded by a short period of pause. Example (1) illustrates that “can” was employed as filler when the speaker keeps repeating “I can.” The speaker appears to be looking for appropriate words or phrases to express her opinion.

(1) Lisa: Because I am…I am a student, I can… I can choose whether I go… I go to the class or not,

And … I can… I can choose whether I… I take a part time job or not.

(Tape 1, Line 59-62)

EFL learners and native English speakers demonstrate different preferences in using modals. The current findings from the EFL learners’ spoken corpus seem to contradict to the studies conducted in an L1 context. Celce-Murcia (1980) examines the link between formality and the choice among the modals and concludes that the regular modals ( such as “should,” “must,” and “may”) are more formal than their “periphrastic” modal equivalents (“ought to,” “have to”). That is, native English speakers would prefer, for instance, to use “have to” rather than to use “must” whereas the data in Table 2 indicates that this is not the case for EFL students.

Another difference in terms of the use of modals is that they are used as a pause-filler when L2

learners need to keep the floor; or modals are used as a hesitation discourse marker while EFL students are searching for the words.

Shields: Probability adverbs

Compared to the previous types of shields--modals, the frequency of occurrence of probability adverbs is significantly low, with an 11.5 %. Actually, “maybe” is the only probability adverb used by EFL learners in the speech sample. It appears to indicate that students might lack practice in probability adverbs such as “probably” or “likely” or they have not learned how to use probability adverbs other than “maybe.” Henceforth, their choice of probability adverbs is restricted to “maybe” only.

In terms of its distribution in an utterance, “maybe” usually occurs in the sentence-initial position. It should be noted that “maybe” usually co-occurs with other kinds of hedges (particularly modals or “I think”) (see examples (2), (3), and (4)). Moreover, “maybe” often precedes or follows a pause or hesitation (see example (3)). The function of “maybe” thus seems to serve as an utterance-initial marker or a pause-filler by EFL subjects in this current study.

(2) Phoenix: Maybe we can talk English in our dormitory. (Tape 6)

(3) Betty: Ya…maybe we can … have class together.

Elaine: We can … in the dormitory … talk English.

Carol: And we can have a day … to be a English day…

Betty: Maybe…everyone just can say English. (Tape 4)

(4) Gigi: Hm…maybe you’re poor, but you can …

you can eat many delicious food in night

market. (Tape 1)

Shields: semi-auxiliaries

The only one semi-auxiliary adopted by students in the data is “seem,” with 2 items out of 399 shields. It is probably due to the reason that the size of the speech sample is too small. Another reason is that “seem” is formal, not suitable for the casual conversation, or that student have not acquired the usage of “seem.” However, further studies need to be conducted to account for the extremely low frequency of occurrence (0.5%) of semi-auxiliaries. Approximators and intensifiers

Table 3 and Table 4 indicate how students use these two types of hedges. In all the hedging devices, approximators (1.1%) and emotionally charged intensifiers (0.6%) only constitute 1.7 % of the total number (667) of hedges used in the sample (see Table 1).

Table 3: Approximators in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse

Approximators Frequency of Occurrence

About 5 71.4%

Somewhat 1 14.3%

a little 1 14.3%

Total 7 100.0%

A particularly intriguing hedging device is the occurrence of “about.” “About” only occurred in Tape 9. In fact, all the five occurrences of “about” were generated by the same speaker. Examples (5) and (6) thus demonstrate all the five uses of “about” in the data:

Table 4: Intensifiers in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse Emotionally charged intensifiers Frequency of Occurrence Actually 2 50.0%

The most important 2 50.0% Total 4 100.0%

(5) Miranda: Do you have a car or … James: No…no…no…

Nicole: When you are twenty? James: About…about…

Miranda: Or because you are a boy, so you have the freedom…

James: About eighteen…eighteen… (Tape 9, line 10-15) (6) Nicole: You earn it…

James: Ya…ya…I earn about … about…twenty-five thousands a month…

(Tape 9, line 81-2)

Owing to the small size of the spoken corpus, the findings seem to be unable to draw a generalization about the use of hedging in EFL spoken data, particularly with respect to the use of approximators and emotionally charged intensifiers. Therefore, further studies need to be conducted in order to explicate the low frequency of occurrence of these two types of hedges.

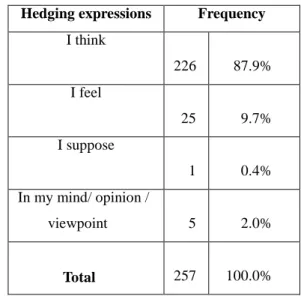

Expressions of the speaker’s personal involvement Table 5 demonstrates how four types of expressions of personal involvement were adopted by EFL learners. “I think” constitutes approximately 88% of all total number of the expressions of personal involvement.

Table 5: Expressions of Personal Involvement in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse

Hedging expressions Frequency I think 226 87.9% I feel 25 9.7% I suppose 1 0.4% In my mind/ opinion / viewpoint 5 2.0% Total 257 100.0%

Among all the hedging expressions, “I think” is the most frequently used hedging devices (33.9%) out of the total of 667 hedges (see Appendix I for a complete list of all the hedges). Hedging devices with similar meaning and function such as “I feel/suppose” and “in my mind/opinion/viewpoint,” together with the hedge “I think,” constitute a substantial part of the hedges identified in this study. (7) and (8) illustrate the use of “I think”:

(7) Alexander: I…I think I can do many things. I can do in daily life

so I think the rest time will be my … hm… will be the time I have the most freedom. And I think the least freedom time I have… I think is the study times.

Because I…I think the study times are I can’t choose what I like or what I don’t like.

(Tape 2, line 18-22)

(8) Bob: Hm…I think I can practice my English with my brother.

My brother now is studying in senior high school.

So I think I can practice English with him every day.

And…I think our English will be better and better.

And another way, I think hm… I can watch film. (Tape 5)

(9) Christine: I think I’m free to do anything. […] Debbie: O.K. I think that I have freedom in the

most area of my daily life. […]

Justine: I think watching a movie is a good way to learn many oral uses in English. […] I think I can try it some day. (Tape 5)

Alexander in example (7) seems to use the hedge “I think” as a utterance or clause-initial marker. He begins his turn by the expression “I think”. Another “I think” is also preceded by a pause (as indicated by the arrow). In example (8), Bob seems not to know how to continue his statement and, accordingly, spends more time on searching for the words. He then uses “I think” to fill the pause while he is searching for words and to hold the floor.

In Examples (7) and (8), both students prefer to use “I think” to fill the pause while they are searching for words or having trouble finding the right words to say what we mean. However, in example (9) the expression “I think” is used as an turn-initial marker: the three speakers use this expression to claim the floor. By this expression “I think,” the speakers are announcing their turn to speak.

In brief, the expression “I think” is used either as a pause-filler while speakers are searching for words, or an utterance-initial marker to claim a turn. The rather high frequency of this expression may be attributed to the fact that some students use this expression to claim the floor. They are likely to begin every sentence with “I think.” Another use of the expression “I think” is similar to the use of modals. It is used as a pause-filler: it is usually followed or

preceded by a period of silence or hesitation.

V. Conclusions

This study is a case study investigating how intermediate EFL learners use hedging expressions in their oral discourse. The findings indicate that the most frequently used hedging devices in this study are shields and expressions of personal involvement. Compared to Salager-Meyer’s (1994) study which concludes that shields, approximators, and compound hedges account for over 90% of the hedges, this current study reveals a similar finding that shields are probably the most preferred hedging devices among EFL students. Although subjects in this study demonstrate a high frequency in using hedging expressions, the types of hedges adopted by EFL learners are mainly restricted to two devices– “modals” and expressions of personal involvement “I think.”

The findings in this current study support previous researches on L1 spoken data in that hedges are useful devices for signaling that a speaker is searching for a word (Coates, 1996; Holmes, 1995). However, there is a discrepancy between L1 and L2 speakers in terms of the types of hedges. For instance, in this study, EFL learners use more formal modals or expressions (such as “must “instead of “have to”, and “I think” instead of “I mean”). Coates (1996) finds that “sort of” and “kind of “are the two hedges most frequently used to keep a conversational floor while a speaker searches for a word. In this study, “I think” is the most frequently used expressions to hold the floor and a pause-marker. One more discrepancy is that in our study EFL learners seldom used hedges to express vagueness or sensitivity to other’s feeling as L1 speakers do.

The limited number of types of hedges in this study may be due to the following reasons: (1) Limited by their oral proficiency, L2 learners have only acquired a small repertoire of hedging

expressions. As a result, they are not skillful in using various hedges. (2)The casual setting, the topic of the conversation, and their intimate relationship probably do not require students to adopt various hedging expressions to show politeness, though further studies need to be made to confirm this inference. Pedagogical Implications

This study finds that the types of hedges used by EFL students are limited and different from those preferred by L1 speakers. The findings suggest that students need explicit instructions of the various forms and functions of hedges. Moreover, EFL material writers should also include such expressions in the textbooks.

Previous studies have also called for the need of explicit instructions of hedges or formulaic expressions. Nikula’s (1996) study reports the correlation between the use of such fillers or hesitation markers to L2 learners’ proficiency level. Her study finds that EFL learners produced a much narrower range of fixed phrases or fillers. In her study, even advanced learners produce a much narrower range of discourse markers than native speakers. These studies support that the use of hedges or fillers is important in L2 speaking performance. Hasselgren (1998), Fukuya & Martinez -Flor (2008), and Wood (2009) all call for explicit instructions or focused instruction of such hedging expressions to improve L2 learner’s fluency.

In a similar vein, the findings in this study support previous studies that students need more explicit instructions to familiarize themselves with appropriate use of hedging expressions. By drawing attention to the use of hedges, students can accordingly increase their awareness to such politeness devices and, therefore, improve their competence in oral communication.

Problems with the taxonomy

The first problem the study encountered has to do with the classification of modals. According to the

taxonomy of hedges adopted in this study, modal verbs “expressing possibility” are counted as hedges. However, it is difficult to make a clear distinction between modals expressing capability and those expressing probability.

Since the goal of this study is to identify the hedges used in the spoken data, no attempt has been made to draw a distinction between modals signaling ability and modals expressing probability. Therefore, all modals in this study were classified as shields. For the sake of convenience in classification, the “periphrastic” modal equivalent-- “have to” was classified as a regular modal. This may partly account for the high frequency of modals occurring in the data.

The second problem is that any taxonomy is intrinsically problematic since no one can provide an exclusive classification of all the hedges occurring in a language. The fact makes the problem more complicated that researchers have reached little agreement on the functions and forms of hedges. The various taxonomies of hedges proposed by different researchers, therefore, make any attempt to provide a classification of hedges inherently problematic in some ways.

According to Low (1996), hedges and intensifiers serve totally different functions. Low (1996) provides a differing taxonomy in which he distinguishes between intensifiers and hedges. He argues that foregrounding devices (or intensifiers) increase “a small set of semantic dimensions,” (p.4) whereas background terms (or hedges) decrease the dimensions.

As a result, there are a number of other expressions which are difficult to locate according to the taxonomy, such as “inevitably.” Because of the limit of this study and their low frequency of occurrence, these expressions are not included. Limitations & Future Directions

hedges, this study has the following limitations. First, the speech sample is rather small. A corpus based on a 140-minute audio recording is rather limited to draw any generalizations about EFL college students’ oral discourse. Further studies based on a larger corpus need to be conducted to find general patterns about how EFL learners use hedging devices.

Another limitation is the rather formal conversational style in some groups. In order to be easily graded by the teacher, some students thus prefer to speak in a monologue form in the group.

Due to the difficulty in the classification mentioned above, the small sample of spoken corpus, and the limited proficiency level of students, the findings seem unable to provide a generalization but they may point to new directions for future research on a larger scale. However, this case study, hopefully, will be able to draw EFL learners’ and teachers’ awareness to this respect. Therefore, further studies need to be conducted to provide a more complete account of how EFL learners employ hedging expressions in their spoken discourse.

Further studies are urged in the following directions: (1) to examine whether there is any correlation between EFL speakers’ level of proficiency and their use of hedging, in terms of the quality and quantity of hedging devices; (2)to conduct a comprehensive analysis of how hedges are treated in current EFL textbooks in Taiwan and to draw pedagogical applications; (3) to undertake a comparative analysis to examine data from both EFL learners and native speakers, using the latter to evaluate the former and to suggest directions for the design of classroom activities.

Learning how to use polite language is of particular importance to college students in Taiwan, who have already mastered enough grammatical knowledge yet lack the skill or training in appropriately and subtly expressing their opinions

with hedging expressions.

References

[1]劉賢軒(1999)。台灣研究所學生所寫英文學術期 刊論文中的謹慎語。行政院國家科學委員會專 題研究計畫。(NSC-88-2411-J-007-018)。 [2]Biq, Y.O. (1990). Question words as hedges in

conversational Chinese: A Q and R exercise. In Bouton L.B. & Kachru, Y. (Eds.), Pragmatics &

Language Learning, Monograph series 1 (pp.141-157). Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois.

[3]Brown, P.; & Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness:

Some universals in language usage. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

[4]Celce-Murica, M. (1980). Contextual analysis of English: Application to TESL, in D. Larsen-Freeman (ed.), Discourse analysis in second

language research. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

[5]Chen, Y. P. (2007). A corpus-based study of hedges in Mandarin spoken discourse. Unpublished Master’s thesis, the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University.

[6]Coates, J. (1996). Women talk: Conversation

between women friends.Oxford: Blackwell.

[7]Coates, J. (1997a). The construction of a collaborative floor in women’s friendly talk.

Conversation: Cognitive, communicative and social perspectives, T. Givon (ed.), 55-89. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

[8]Coates, J. (1997b). Women’s friendships, women’s talk. Gender and discourse, R. Wodak (ed.), 245– London: SAGE Publications.

[9]Coates, J. (2003). Men talk: Stories in the making

of masculinities. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

[10]Crompton, P. (1997). Hedging in academic writing: Some theoretical problems. English for

[11]Crompton, P. (1998). Identifying hedges: Definition or divination? English for Specific

Purposes, 17, 303-311.

[12]Freeman, F. & B. McElhinny. (1996). Language and gender. Sociolinguistics and language teaching, in S. McKay & N. Hornberger (eds.), 218-280. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[13]Fukuya, Y. & Martinez-Flor, A. (2008). The interactive effects of pragmatic-eliciting tasks and pragmatic instruction. Foreign Language Annals, 41(3): 478-500.

[14]Givon, T. (1993). English Grammar -- A

Function- Based Introduction, Vol. I. Philadelphia:

John Benjamins Publishing Company.

[15]Grundy, P. (1994). Context-learner context, in P. Franklin and H. Purschel (eds), Intercultural

communication in institutional settings.

Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

[16]Grundy, P. (1995). Doing pragmatics. New York: Edward Arnold.

[17]Hasselgren, A. (1998). Smallwords and valid

testing. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of English, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. Cited in Luoma, S. (2004),

Assessing speaking, Cambridge University Press.

[18]Hinkel, E. (1997). Indirectness in L1 and L2 academic writing. Journal of Pragmatics 27(3), 361-386.

[19]Holmes, J. (1984). Hedging your bets and sitting on the fence: some evidence for hedges as support structures. Te Reo 27, 47-62.

[20]Holmes, J. (1986). Functions of ‘you know’ in women’s and men’s speech. Language in Society 15.1: 1-22.

[21]Holmes, J. (1995). Women, men and politeness. London: Longman.

[22]Hyland, K. (1994). Hedging in academic writing and EAP textbooks. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 239-256.

[23]Hyland, K. (1996). Writing without conviction?

Hedging in science research articles. Applied

Linguistics, 17(4): 433-454.

[24]Hyland, K. (1998). Hedging in scientific research articles. John Benjamin Publishing Company.

[25]Hyland, K. (2000). Hedges, boosters and lexical invisibility. Language Awareness, 9, 179-197. [26]Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions:

metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. Journal

of Second Language Writing, 13(2): 133-151.

[27]Hyland, K. (2006). English for academic purposes: An advanced resource book. New York: Routledge.

[28]Lakoff, G. (1972). Hedges: a study in meaning criteria and the logic of fuzzy concepts. In P. Peranteau, J. Levi and G. Phares (eds.), Papers

from the Eighth Regional Meeting, Chicago

Lingistics Society.

[29]Lakoff, R. (1975). Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper & Row.

[30]Levinson, S. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[31]Lewin, B.A. (2005). Hedging: an exploratory study of authors’ and reader’s identification of ‘toning down’ in scientific texts. Journal of

English for Academic Purposes, 4, 163-178.

[32]Lin, H.O. (1999) Reported speech in Mandarin

Chinese. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University.

[33]Lindemann, S., & Mauranen, A. (2001). “It’s just real messy”: The occurrence and function of just in a corpus of academic speech. English for Specific

Purposes, 20, 459-475.

[34]Low, G. (1996). Intensifiers and hedges in questionnaire items and the lexical invisibility hypothesis. Applied Linguistics, 17(1): 1-37. [35]Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing speaking.

Cambridge University Press.

Oxford: Blackwell.

[37]Nikula, T. (1996). Pragmatic Force Modifiers: A study in interlanguage pragmatics. PhD thesis, Department of English, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, FI., cited in Luoma, S. (2004),

Assessing speaking, Cambridge University Press.

[38]Powell, M. (1985). Purposive vagueness: An evaluative dimension of vague quantifying expressions. Journal of Linguistics, 21(1): 31-50 [39]Prince, E. F., Frader, R. J., & Bosk, C. (1982).

On hedging in physician-physician discourse. In J. di Prieto (Ed.), Linguistics and the Professions (pp. 83-97). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

[40]Salager-Meyer, F. (1994). Hedges and textual communicative function in medical English written discourse. English for Specific Purposes, 13, 149-170.

[41]Salager-Meyer, F. (1998). Language is not a physical object. English for Specific Purposes, 17, 295-302.

[42]Salager-Meyer, F. (2000). Procrustes’ recipe: Hedging and positivism. English for Specific

Purposes, 19, 175-187.

[43]Shirato, J. & Stapleton, P. (2007). Comparing English vocabulary in a spoken learner corpus with a native speaker corpus: Pedagogical implications arising from an empirical study in Japan. Language Teaching Research, 11 (4): 393-412.

[44]Skelton, J. (1988). The care and maintenance of hedges. ELT Journal, 42(1): 37-43.

[45]Stubbs, M. (1986). A matter of prolonged field work: Notes toward a modal grammar of English.

Applied Linguistics, 7(1): 1-25.

[46]Swales, J. (1990). Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[47]Tannen, D. 1986. That’s not what I meant. New York: Ballantine Books.

[48]Tannen, D. 1994. Gender and discourse. New

York: Oxford University Press.

[49]Wood, D. (2009). Effects of focused instruction of formulaic sequences on fluent expression in second language narratives: a case study.

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 12(1):

39-57.

[50]Yu, S. (2009). The pragmatic development of hedging in EFL learners. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Department of English, City University of Hong Kong.

Appendix I A Taxonomy of Hedges in EFL Learners’ Oral Discourse

Hedging expressions Frequency Expressions of personal involvement

I think 226 33.9%

I feel 25 3.8%

I suppose 1 0.4%

in my mind / opinion / viewpoint 5 0.75% Modals can 204 30.6% will 100 15.0% must 19 2.8% should 12 1.8% have to 11 1.6% may 4 0.6% would 1 0.15% Probability Adverbs maybe 46 6.9% Semi-Auxiliaries seem 2 0.3% Approximators about 5 0.75% somewhat 1 0.15% a little 1 0.15%

Emotionally charged intensifiers

actually 2 0.3%

the most important 2 0.3%