Learning to be Australian:

Adaptation and Identity

Formation of Young

Taiwanese-Chinese Immigrants in

Melbourne, Australia

Lan-Hung Nora Chiang and Chih-Hsiang Sean Yang

Most immigrant parents cannot or will not send their children back home. They rely instead on the strength of their community or of their family to help preserve some connection with the old country and, through these, some semblance of parental authority. They take their children to church or temple, surround them with relatives, pepper them with proverbs in the home language, and sing karaoke with them in an effort to stem dissonant acculturation.1

Background and research questions

S

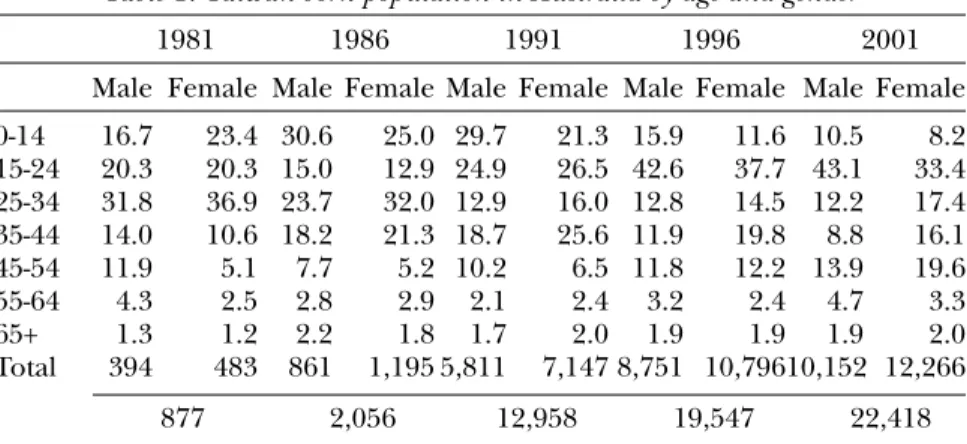

ince the early 1980s, one of the most popular migration destinations for middle-class Taiwanese immigrants has been Australia. The Taiwanese have migrated mainly to obtain better educational environments for their children and particularly to evade the military service required of young men in Taiwan.2As shown in table 1, for the last two census periods, those aged between 15 and 24 years of age formed the largest group of Taiwan-born individuals living in Australia. These young people included the fi rst generation of those born in Taiwan, who immigrated with their parents, and unaccompanied __________________

1 Alejandro Portes and Rubén G. Rumbaut, Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 232.

2 Military service is compulsory to this day, although it varies from strenuous

one-year-and-ten-months training to working in government or academic institutions for up to four years. Previous studies of Taiwanese migrants in Australia (see Chiang and Hsu, Taiwanese in Australia) have shown that some parents make an effort to send their male children abroad, sometimes to a third country, to evade military service, before getting an immigration visa to the destination country. Male children usually leave Taiwan freely before the age of 16 without having completed their military service. Those who have not completed military service before emigration are obliged to complete it on returning. Some avoid doing this by going abroad every four months (extended after the fi rst two months), the maximum amount of time a foreign passport holder can stay in Taiwan without formal residency status. This arrangement is easier if one works in the private sector.

sojourners who stayed in Australia on their own. The literature on Taiwanese immigrants in Australia has largely overlooked these young people, whether born in Taiwan or Australia, in spite of their large number. As they now complete their education, it is meaningful to investigate how well they do compared with their parents, who faced status dislocation in their economic achievement or diffi culties in fi nding jobs or seeking better business op-portunities in Taiwan.3

Table 1. Taiwan-born population in Australia by age and gender

1981 1986 1991 1996 2001

Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female

0-14 16.7 23.4 30.6 25.0 29.7 21.3 15.9 11.6 10.5 8.2 15-24 20.3 20.3 15.0 12.9 24.9 26.5 42.6 37.7 43.1 33.4 25-34 31.8 36.9 23.7 32.0 12.9 16.0 12.8 14.5 12.2 17.4 35-44 14.0 10.6 18.2 21.3 18.7 25.6 11.9 19.8 8.8 16.1 45-54 11.9 5.1 7.7 5.2 10.2 6.5 11.8 12.2 13.9 19.6 55-64 4.3 2.5 2.8 2.9 2.1 2.4 3.2 2.4 4.7 3.3 65+ 1.3 1.2 2.2 1.8 1.7 2.0 1.9 1.9 1.9 2.0 Total 394 483 861 1,195 5,811 7,147 8,751 10,796 10,152 12,266 877 2,056 12,958 19,547 22,418

Source: Compiled from unpublished data, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of

Population and Housing, 1981, 1991, 1996, and 2001.

A majority of Hong Kong and Taiwanese immigrants arrived in Australia under the Business Migration Program (BMP), with many “astronaut” house-holds, where the parents travelled regularly back to Hong Kong or Taiwan to keep their businesses running and visiting their children for parts of the year.4 Pe-Pua et al. noted that frequent travel could lead to emotional stress for couples and to role reversals between men and women and between children and parents. In the family, children may be confused as to what values to adopt: assertiveness, independence and individualism as taught in school, or conformity, humility and obedience as taught at home.5

__________________

3 Lan-hung Nora Chiang, “Dynamics of Self-Employment and Ethnic Business among Taiwanese

in Australia,” International Migration, vol. 42, no. 2 (2004), pp. 153-173.

4 David Ip, “A Decade of Taiwanese Migrant Settlement in Australia: Comparisons with Mainland

Chinese and Hong Kong Settlers,” Journal of Population Studies, vol. 23 (2001), pp. 113-145; Lan-hung Nora Chiang, “Immigrant Taiwanese Women in the Process of Adapting to Life in Australia: Case Studies from Transnational Households,” in David Ip, Ray Hibbins and Wing Hong Chui, eds.,

Ex-periences of Transnational Chinese Migrants in the Asia-Pacifi c (New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.,

2006), pp. 69-86; Lan-hung Nora Chiang and Richard Hsu, “Taiwanese in Australia: Two Decades of Settlement Experiences,” Geography Research Forum, vol. 26 (2006), pp. 32-60.

5 Rogelia Pe-Pua, Colleen Mitchell, Stephen Castles and Robyn Iredale, “Astronaut Families

and Parachute Children: Hong Kong Immigrants in Australia,” in Elizabeth Sinn, ed., The Last Half

Migration may lead to the loss of a Chinese identity and values, as par-ents in some “astronaut” families fi nd it diffi cult to discipline and control their children, and to ensure that they grow up following the traditional value system. Hsu took a close look at split-household children in Canada, where she found a reconfi guration of the traditional family structure based on the creation of various transnational connections linking the same fam-ily in Taiwan and in Vancouver.6 The children have learned to negotiate within “astronaut” families by situating themselves somewhere between being Taiwanese and being Canadian.

In this study, the authors look at a small group of young Taiwanese trans-nationals who immigrated to Australia with their parents to study, their process of adaptation through social and economic relations, and the forma-tion of their self-identities in Australia. Because previous research showed that parental infl uences on identity are inevitable, we would like to fi nd out what role parents play in their children’s decision to migrate, and the extent of their cultural infl uences on the 1.5 generation, which refers to people who immigrated as children, usually accompanied by their parents, but who grew up and attended school in the host country. Second generation refers to children who were born of immigrants in the host country. Furthermore, we seek to understand how the transnational experiences of the younger generation develop over time, and how they challenge parental authority.

Literature Review

The language barrier tops the list of problems faced by Taiwanese im-migrants, preventing them from fi nding suitable employment despite their high levels of education and entrepreneurship.7 It can be assumed that the language barrier is greatly reduced among second-generation immigrants, regardless of their subethnicity.

Non-recognition of their qualifications poses another major diffi-culty. Ethnographic analysis shows that Taiwanese immigrants, with their backgrounds as successful business people with capital and expertise in manufacturing, export and international marketing, fi nd it hard to take up work that is not commensurate with their educational and economic background. They are therefore unlikely to become wage/salary earners in the host country. Other diffi culties faced by immigrants include a lack of __________________

6 Wei-Shan Hsu, “Reconstituted Lives: Children’s Experiences in the Context of Transnational

Migration between Canada and Taiwan” (master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, 2002).

7 David Ip, Chung-Tong Wu and Christine Inglis, “Settlement Experience of Taiwanese

Immi-grants in Australia,” Asian Studies Review, vol. 22, no. 1 (1998), pp. 79-97; Ip, A Decade of Taiwanese Migrant Settlement; Chung-Tong Wu, “New Middle-class Chinese Settlers in Australia and the Spatial Transformation of Settlement in Sydney,” in Laurence Ma and Carolyn Cartier, eds., The Chinese

Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility, and Identity (New York: Rowman & Littlefi eld Publishers, Inc., 2003);

familiarity with the Australian business culture, labour relations and com-plex rules and regulations, the small size of the market and higher taxes compared to Taiwan.8

Many former business immigrants pursue post-graduate degrees or attend technological and further education (TAFE) courses, which are offered in Australia to provide professional training and certifi cation to help people obtain work. Some might engage in various types of self-employment. Often the male head of the household, the major bread-earner, goes back to work in Taiwan to support his family in Australia, much like Hong Kong nationals have done in North America and Australasia.9 By the same token, a number of Taiwanese have returned to Taiwan, including young fi rst-generation migrants.10 Better opportunities for employment and business, and social support networks, were strong motivating factors for all potential Taiwanese returnees, though many anticipated returning or returning intermittently to maintain the business in Taiwan.11

The literature reviewed above provided the background for an investiga-tion of the young fi rst generainvestiga-tion of Taiwanese immigrants in Australia. This paper sets out to explore the identities of what is frequently referred to as the “1.5 generation” of the Taiwanese communities in Melbourne.This “1.5 generation” comprises people who emigrated to Australia as children, usually accompanied by their parents, and who grew up and attended school in the destination country.12 Given the relatively short history of their settlement in Australia, many of the migrant children are of the “1.5” rather than the second generation. Although the younger generation of migrants is better acculturated than their parents, they are less acculturated than second-generation immigrants, and would be expected to face other problems of adjustment.13

Young transnational migrants have recently received attention in other settings. Using ethnographic case studies and a survey of second-generation __________________

8 Chiang, Dynamics of Self-Employment.

9 Pe-Pua et al., Astronaut Families; Elsie Ho, “Multi-local Residence, Transnational Networks:

Chinese ‘Astronaut’ Families in New Zealand,” Asian and Pacifi c Migration Journal, vol. 11, no. 1 (2002), pp. 145-164; Johanna L. Waters, “Flexible Families? ‘Astronaut’ Households and the Experiences of Lone Mothers in Vancouver, British Columbia,” Social and Cultural Geography, vol. 3, no. 2 (2002), pp. 118-134; David Ley and Johanna L. Waters, “Transnationalism and the Geographical Imperative,” in Peter Jackson, Mike Crang and Claire Dwyer, eds., Transnational Spaces (London: Routledge Press, 2004), pp. 104-121.

10 Lan-hung Nora Chiang and Pei-chun Sunny Liao, “Back to base: Adaptation and self-identity

of young Taiwanese trans-nationals,” Occasional Paper No. 18 (Pingtung, Taiwan: National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2006).

11 Robyn Iredale, Fei Guo and Santi Rozario, Return Migration in the Asia Pacifi c (Cheltenham,

UK: Edward Elgar, 2003), p. 38.

12 Peggy Levitt and Mary C. Waters, eds., The Changing Face of Home: The Trans-National Lives of

the Second Generation (New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press, 2004), p. 12.

13 Lai Kuen Wong, “Young Lives in Australia: Stress and Coping of Hong Kong Chinese

Adoles-cent Immigrants” (Ph.D. thesis, University of New South Wales, School of Social Work, 1997); Pe-Pua

schoolchildren in Miami and San Diego, Portes and Zhou have made an argument that second-generation immigrants restricted to poor inner-city schools, bad jobs and shrinking economic niches will experience downward mobility.14 The psychology of the second generation that Portes and Rumbaut studied revealed that the humble aspirations of Mexican Americans are a refl ection of the negative incorporation of their parents. On the other hand, higher parental status and unbroken families support fl uent bilingualism and other manifestations of selective acculturation that, in turn, increase self-esteem, reinforce aspirations, and lower psychological distress.15

The literature on Taiwanese immigrants has largely overlooked the younger generation, partly because of their “passive”migrant status.16 Recent studies on transnational families in Hong Kong and Taiwan may shed some light on the issue. Pe-Pua et al. used the term “parachute kids” for children living with one parent or with both parents back in Hong Kong.17 Wong investigated the Hong Kong Chinese adolescent immigrants’ mental health, their experience of daily hassles, and their perceptions of stress and social support from friends and family.18 Teenagers with little English-language skills on arrival have great diffi culties with their studies in school, as well as with establishing peer rela-tionships, particularly in schools where Chinese enrolments are low.

Immigrant parents’ expectations do not just relate to academic perfor-mance; they often uphold the Chinese traditional value of fi lial piety, and expect their children to accept their advice on various aspects of life, includ-ing management of time, leisure activities, datinclud-ing, retaininclud-ing the Chinese culture through speaking Chinese at home, and preparation for future careers. A generation gap has widened between parents and children, lead-ing to feellead-ings of confusion stemmlead-ing from the confl ictlead-ing expectations of parents and peers.

Several studies illustrated that such “ancient values” still exist in parent-child relationships. Many recent adolescent immigrants from Hong Kong experience considerably increased responsibilities at home, including household chores, gardening, shopping, doing minor repair work, contact-ing overseas family members and relatives, and in some families actcontact-ing as interpreter for parents and relatives who have weak English-language skills, and taking care of younger siblings while both of the “astronaut” parents are away from Australia.19 Some children become more mature and independent __________________

14 Alejandro Portes and Min Zhou, “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and

its Variants,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 530 (1993), pp. 74-97.

15 Portes and Rumbaut, Legacies, p. 231.

16 The word denotes the role played by members of the family other than the chief applicant

for immigrant status.

17 Pe-Pua et al., Astronaut Families. 18 Wong, Young Lives in Australia.

19 Pookong Kee and Ronald Skeldon, “The Migration and Settlement of Hong Kong Chinese

in Australia,” in Ronald Skeldon, ed., Reluctant Exiles? Migration from Hong Kong and the New Overseas

as a result of handling all the changes and challenges, but some may experi-ence tremendous stress and exhibit symptoms of maladjustment.

An early study of Taiwanese immigrants by Lee noted that some children tend to follow their parents’ values in how they perceive Australians, and therefore showed low levels of assimilation since they would not shed their Taiwanese identity.20 More recently, Hsu and Ip found that the “1.5 genera-tion” immigrants whom they interviewed not only asserted their identities as Taiwanese, but they also subscribed to values that are characteristically traditional, and frequently followed well-accepted Chinese gender lines.21 Despite Taiwan’s rapid transition to industrialization, modernization and political liberalization, patriarchal values remain strong, as refl ected in tra-ditional gender roles in the family, and parent-child relationships.22

The literature on Taiwanese immigration to Australia shows that very rarely is the younger generation studied as individuals without any consideration of the generational relationship to their parents. Of late, Chiang and Liao attempted to address the issue of return migration by a qualitative study of adaptation and self-identity of young Taiwanese transnationals.23 Returning to Taiwan not because of poor adjustment in Australia, but because of better employment opportunities at the time of return, they constantly needed to adapt to both Taiwanese and Australian environments, developing a dual/ situated identity. They fi t the description of transnationals by Portes in that they are “often bilingual, move easily between different cultures, frequently maintain homes in two countries, and pursue economic, political and cultural interests that require their presence in both.”24

Methodology

It should be noted that there is an undercount of Taiwanese in the Australian census, as some Taiwanese immigrants were actually born in China before they moved to Taiwan with the nationalist government in

__________________

20 Australia dropped the idea of assimilation in 1960, and the policy was replaced by

“integra-tion.” The word “assimilation” was used in Lee’s work. See Shen Rui Lee, “The Attitude of Taiwanese Immigrants in Brisbane towards Assimilation: An Internal Perspective” (B.A. Honours thesis, Griffi th University, Brisbane, Australia, 1992).

21 Jung-Chung Hsu and David Ip, “Gender Role and Self among 1 ½ Generation Taiwanese

Migrants in Australia” (paper presented at the 9th Biennial Conference, Chinese Studies Association of Australia, Bendigo, Australia, July 2005).

22 For traditional gender roles, see Nora Chiang, “The New Women of Taiwan: Participation and

Emancipation,” Occasional Paper No. 1 (Pingtung, Taiwan: National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2003). For parent-child relationships, see An-Chi Tung, Chaonan Chen and Paul Ke-Chih Liu, “The Emergence of the Neo-Extended Family in Contemporary Taiwan,” Journal of Population Studies, vol. 32 (2006), pp. 123-152.

23 Chiang and Liao, Back to base.

24 Alejandro Portes, “Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and

1949.25 Field studies of Taiwanese migrants should therefore cautiously treat “place of birth” as a defi ning category, and focus rather on the immigrant’s cultural origin and nationalist ties, since they infl uence their adaptation and self-identity.

This study is based on in-depth interviews and observation of young Taiwan-born immigrants in Melbourne. The city recorded a population of 3.6 million in 2004 and is rated as one of the ten most livable cities in the world by the Economist Intelligence Unit, despite its bad weather (“four seasons in one day”). As one-third of its population is overseas-born, it is a welcoming community to 140 ethnic groups. Melbourne is considered the “cultural city” (wen hua zhi tu) in the eyes of the Taiwanese who brought their children to Australia for better education opportunities.

Melbourne was chosen as the site of the study because contacts were made previously by one of the authors, Chiang, with parents of the “1.5 generation” and various Taiwanese associations. Most informants were recruited through snowball sampling, beginning with personal contacts of the host family where the other author, Yang, stayed, and extended through local Taiwanese com-munity organizations and respondents’ connections. Altogether, fi eldwork took place for one month between June and July 2005. Mandarin Chinese was used throughout, and each interview lasted between one-and-a-half to three hours, thus generating qualitative data for analysis in the later sections.

Research Findings

Profi le of Young Immigrants

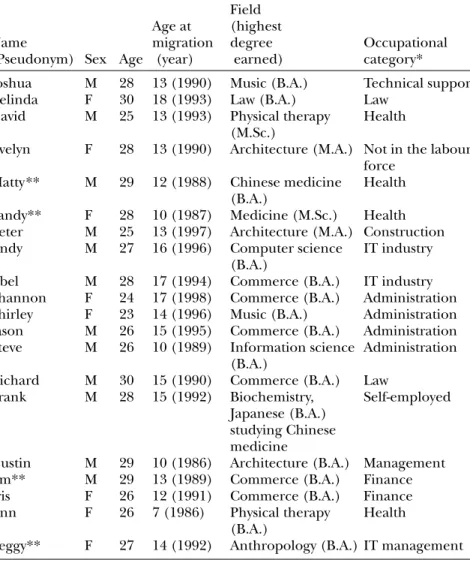

Among the 20 interviewees, there were 12 males and 8 females, ranging in age from 23 to 30 years old, as shown in table 2. Most (16) of them were single, ranging in age from 7 to 18 years old at the time of migration. Most male migrants moved between the ages of 10 and 15, before they reached the age when they could not leave before fulfi llment of military service. On the other hand, a wider age range (7-18) was found among females at the time of migration. They are all Taiwan-born and Mandarin speaking; but whether their parents were born in Taiwan or Mainland China is not known to the authors.

Half of the interviewees had lived in Australia for more than 14 years, while the other half had lived in Australia from 7 to 14 years. While most (19) of __________________

25 In this paper the term “Taiwanese” refers to all the inhabitants of Taiwan of Chinese ancestry.

They consist of three distinct groups defi ned in part by the island's peculiar political history: the Main-landers (Chinese and their descendants who migrated to Taiwan between 1945-1949, about 13 percent of the population); the Hoklo (Chinese and their descendants who migrated from Fujian province in the late seventeenth century, about 70 percent); and the Hakka (Chinese and their descendants who migrated from Guangdong province later, about 15 percent). The latter two are known collectively as the “native Taiwanese,” and have contributed the bulk of the migrants of the post-1950 era.

the interviewees moved during high school, 14 moved with their parents under Australia’s Business Migration Program, and the rest came to school by themselves fi rst, with their parents following later. Four of the interviewees had earned master’s degrees, while the rest had obtained bachelor’s degrees. Except for one who is looking for work overseas, they were all employed at the time of the interview. As the authors use a snowball sampling method,

Table 2: Description of respondents

Field

Age at (highest

Name migration degree Occupational

(Pseudonym) Sex Age (year) earned) category*

Joshua M 28 13 (1990) Music (B.A.) Technical support

Belinda F 30 18 (1993) Law (B.A.) Law

David M 25 13 (1993) Physical therapy Health

(M.Sc.)

Evelyn F 28 13 (1990) Architecture (M.A.) Not in the labour

force

Matty** M 29 12 (1988) Chinese medicine Health

(B.A.)

Sandy** F 28 10 (1987) Medicine (M.Sc.) Health

Peter M 25 13 (1997) Architecture (M.A.) Construction

Andy M 27 16 (1996) Computer science IT industry

(B.A.)

Abel M 28 17 (1994) Commerce (B.A.) IT industry

Shannon F 24 17 (1998) Commerce (B.A.) Administration

Shirley F 23 14 (1996) Music (B.A.) Administration

Jason M 26 15 (1995) Commerce (B.A.) Administration

Steve M 26 10 (1989) Information science Administration

(B.A.)

Richard M 30 15 (1990) Commerce (B.A.) Law

Frank M 28 15 (1992) Biochemistry, Self-employed

Japanese (B.A.)

studying Chinese

medicine

Dustin M 29 10 (1986) Architecture (B.A.) Management

Jim** M 29 13 (1989) Commerce (B.A.) Finance

Iris F 26 12 (1991) Commerce (B.A.) Finance

Ann F 26 7 (1986) Physical therapy Health

(B.A.)

Peggy** F 27 14 (1992) Anthropology (B.A.) IT management

Note: All names are pseudonyms.

* Occupations have been changed to more generic occupational categories to make it more diffi cult to identify interviewees.

they may have left out informants who were not connected to the Taiwanese organizations and key informants who helped them to fi nd interviewees, or those who were not willing or available to be interviewed.

Reasons for Migration and Settlement

In addition to being attracted to Australia’s natural and social environment, previous studies found that immigrants perceived education in Australia to be better than that available in Taiwan.26 Even though parents believed that they were immigrating for the sake of their children’s education, it is quite common that young members of the family werenot asked their opinion on whether to emigrate or not, and were not given a role in the decision-making process. One of the “passive” young migrants recalled:

When I was ten years old, my parents brought me over to study English. I was told that I would be coming to Australia only two months before I left Taiwan. My mother actually took a tour in Australia fi rst, and she decided to immigrate because she liked the environment here. She went back to Taiwan and came back with my dad who had some friends here. My brother and I followed within a month.

Adaptation

Overcoming the language barrier

Learning English was the fi rst challenge faced by newcomers to Australia. Although some of them had attended supplementary English schools (bu xi ban) before migration, they could not use English effectively when they fi rst migrated for three main reasons: they were unfamiliar with the Australian accent, did not know the Australian English-speaking environment, and the English they had learned proved useless. Even though they went through language schools and were assisted by ESL teachers in Australian schools, their studies were affected because of their poor language skills. The only subject that migrants did well in was mathematics. After six months to one year in school, they improved greatly and spoke English fl uently, although not as well as they wished, nor as well as other native speakers in the same class.

The age of the child at migration made a difference. Ann, who migrated at age 7, had few problems with English:

I learned my English mostly from Australia. … I had supplementary English (bu xi ban) for one year before coming to Australia. I went to a public school in Kew right away when I fi rst came at 7. I think my English is now as good as others.

__________________

On the other hand, they all spoke Chinese at home with their parents, although they found that their Chinese had stagnated since their move to Australia.27 However, they spoke Mandarin fl uently in our interviews. They complied with their parents’ request to speak Chinese at home not so much for “cultural preservation” but to maintain their bilingual status and to keep up their competitiveness on the job market in the future. Now working as a systems administrator, Steve explains:

Australia is a multi-national country. I feel that if I master one more language, I will be more competitive in the future. Most Australians can speak only one language, but we are lucky to speak two.

In fact, when young immigrants applied for universities overseas, they used their fl uency in Chinese to fulfi l language requirements or to get extra credit. This helped them to make up for their defi ciencies in other subjects due to their low English profi ciency.

In reality, the longer young migrants stay in Australia, the more their Chinese-language skills suffer. For example, although Matty has a bachelor’s degree in Chinese medicine, he could not get accreditation in Taiwan: after spending 17 years in Australia, he did not pass the medical examination in Taiwan because he could not read or write Chinese. The Chinese language not only helps them as a second language and increases their competitive-ness in the Australian job market, but also enables them to meet friends who speak Chinese, while building a Taiwanese-Chinese identity.

Facing differences in the education system

In previous studies, parents often mentioned that they wanted to spare their children the suffering imposed by the Taiwanese high-pressure educa-tion system.28 However, our informants said that although they had a light workload up to grade 10 in Australia, they started to feel the pressure in grade 11 when they prepared for admission to universities. In order to bet-ter their grades they received supplementary tutoring at home, mostly in mathematics and English. Australia does not administer a sole university entrance examination, as does Taiwan.

__________________

27 Although they speak Chinese well, and speak different Chinese dialects (the mother tongues

of their parents) at home, it would not help them with their written Chinese competency. In Australia, they have less chance to use Chinese in their homework or examinations than in Taiwan, although some of them selected Chinese as their fi rst or second language in school.

28 “Too much memorization and competition … even in primary school in Taiwan” was noted

by Iredale, Guo and Rozario, Return Migration. Harsh treatment by teachers in Taiwan is vividly pre-sented in a popular novel by Ping Ying, Chu Zou Niu Xi Lan [Fleeing to New Zealand: An Educational Experiment of a Mother] (Taipei: Commonwealth Publishing Co., 1995) and commonly brought up by interviewees. In Taiwan, one competes mainly through the Joint Entrance Examination to get into university; this creates a situation where students start to feel the pressure long before they reach grade 12.

Sandy, who came to Australia at 10 to start junior high school, recalled: I had very long school hours in Taiwan, lots of homework, supplementary school (bu xi ban) education, and pressure. There were a lot of exami-nations, and my parents knew that we were under stress. In Australia, we don’t have that many school hours, and the kids go playing after school, exercise, or do other things. Our parents want us to grow up happily here.

Parents who support their children’s education in Australia are strongly involved in their children’s choice of subjects. At the time of the interviews, in-formants had already completed their tertiary education up to the bachelor’s or master’s level. They studied in fi elds considered popular in Taiwan, such as medicine, law, commerce, architecture, computer science, engineering and information technology. Like many students in Taiwan, their choice of subject was infl uenced by perceived job prospects or by their parents. With a B.A. in music, Joshua worked as a systems analyst. He recalled fi ghting with his parents about going to music school:

For them, having an interest in music is OK as a hobby, but to major in music at the university is something else. They did not want to see me ‘starve to death’ as a musician in the future … but I still insisted on choosing music as a major. They did not want to pay my school fees, and suggested that they would only pay if I studied computer science … I was almost kicked out of home.

Choosing careers

Because of the Australian accreditation system, specialized fi elds of study lead to specialized types of employment. Professionalism and specialization were valued in getting jobs, as noted by Sandy who, with a degree in medi-cine, was looking for work:

In Australia specialization counts in getting work. One cannot practice in an area different from one’s training. In Taiwan, if you are an oculist, you cover all areas.

Another consideration in getting jobs is whether companies are run by an Australian or a Taiwanese. It is believed that Australian companies have the advantage of better management styles and employment benefi ts, as noted by several of our informants:

If I stayed in Australia for a long period of time, I would not consider employment at a company owned by an Asian. The social benefi ts and insurance are better in Australian-owned companies. (Shannon, 24, administration)

Asians bring their culture here, and I don’t want to work in such com-panies. I want to work in an Australian-owned company, because I am in

Australia, and I am getting used to the Australian working style. If I work in companies owned by Taiwanese or Asians, it may be harder for me to fi nd work in Australian-owned companies in the future. I would get exposed to various work experiences in an Australian-owned company that does not depend on guanxi (the politics of relationships) as much. (Steve, 26, administration)

After graduation, I worked for eight months in an Asian company, and found that I was not used to the Chinese work culture. The more years I would work, the greater the responsibility I would have but without a fair pay raise … I think it is unreasonable. (Jason, 26, administration)

Given the opportunity to work outside Australia, young immigrants would do so. Moreover, they would avoid working for Asian companies since they tend to be more “exploitative”: long work hours, responsibilities not clearly spelled out, and unfair salaries. Yet, in Australian-owned companies they maintained a friendly and distant relationship with other employees due to language and cultural differences.

When informants were asked if they could see themselves returning to work in Taiwan, they mostly answered in the negative. Some were not willing to give up the Australian “lifestyle,” and others felt that they did not speak Chinese well enough. Having immigrated when she was 7 years old, and working as a therapist among Australians, Ann felt very comfortable in her workplace, even though she was the only Asian in the Australian-owned clinic. Most of our informants were happy about working in Australia and enjoyed their dual identity. They also believed in making a difference as Asians in Australia, since they are often industrious and work long hours. Our con-versations revealed that shop hours and work hours at Australian companies were often extended, as immigrants are used to working long hours, and are also accustomed to the bustling night life in urban Taiwan.

Identity formation

Were informants Australian or Taiwanese? Since childhood they were socialized culturally as Chinese and most single informants still lived with their parents. Some considered themselves Australian, some Taiwanese, and some both Australian and Taiwanese. Those who moved to Australia at a young age tended to speak English only (except with family members), and typically did not have any Chinese or Asian friends. This was the case for Ann, who had lived in Australia for 19 years:

I think I am Australian since I grew up here. Although my skin colour is yellow and I come from Taiwan, I speak perfect English, and am familiar with Australian current affairs. I know nothing about Taiwan and I do not have a single friend from Taiwan here.

Most of the informants claimed to embrace their dual identity, typically answering, “I am both Australian and Taiwanese.” They knew something

about current events in Taiwan, had some Taiwanese friends, and their iden-tity was “positional,” depending on whether they were at home, at school, or in Australian or Taiwanese society.

Parental power

Our informants declared that they were capable of communicating in Chinese at home, and accepted their parents’ nurturing style. However, they would choose to bring up their own children in more liberal ways than those of their parents. They believed in a more “egalitarian” way of treating children, as in Australian families. They wished for more freedom from their parents in their day-to-day activities, and were sensitive to their parents’ infl u-ence in matters such as choosing their subject of study. David talked about his father’s opinions in this way:

My dad sounded like he would not interfere with what I wanted to study, but he actually wanted me to study medicine, but made me believe that I chose to do so.

Our informants clearly felt the hierarchical relation between their par-ents and themselves when they were exposed to parpar-ents and children being equals or friends in Western families. The differences in family expectations sometimes posed a problem when they participated in school activities. Occasionally, they faced the confl icting demands of their parents and peers in everyday matters. As David explained,

[i]t is sometimes painful to be caught in the middle, if you want to be Chinese and Western at the same time. If you want to colour your hair, for example, you would consider your family’s opinion, whereas the Australian mother supports the child’s decision and disregards the rules of the school.

Even if the young Taiwanese did not agree with their parents, they avoided using a confrontational approach. Since they knew that their parents did not understand English, they spoke English to create their own “space of autonomy and power” at home. By doing so they took better control of the relationship with their parents and the latter became less domineering. The following example from Ann illustrates the situation:

We speak English to our friends in face-to-face conversation and over the phone. If we use English, our parents do not know our secrets, since their English is not so good … When I meet Taiwanese my age, I normally speak English; but my parents told me to use Chinese as much as I can.

Young Taiwanese who lived with their parents had limited freedom: they could not return home late or spend the night at a friend’s home. As a result,

they tended to associate with either Asians from Hong Kong or other Chinese whose parents made similar demands:

Wai guo ren (non-Chinese) invite friends over for parties at home, but zhong guo ren (Chinese) are more reserved. I join these parties anyway,

even though my parents may have some reservations over this. Sometimes I have parties too and must reassure my parents that most of my friends are Asians; but I need to tell them ahead of time, otherwise, they would not be used to seeing Westerners in my home. (David)

My friends are mostly from Asia, such as Singapore; but I am quite mul-ticultural. I do have some limitations as to who my friends are because of my family. (Joshua)

Financially dependent on their parents, the young had to submit to their parents’ approval of their friends. These fi ndings support those of studies conducted with young Hong Kong immigrants to Australia and young return migrants from Australia.29 Inevitably, when the young children were exposed to Australian culture, they developed views that often confl icted with those held by their parents. They started to wonder why their parents were differ-ent from Australian pardiffer-ents, who would not require children to come back home early in the evening, nor expect them to choose certain subjects as majors. In this case the generation gap stemmed from differences in values and on the parents’ insistence on traditional behaviour and authority over their children. This is why many young immigrants conclude: “I will not treat my children the way my parents treat me.”

Peer relationships

Similar cultural backgrounds can draw young migrants together into small groups. Our informants’ identities are primarily built on language, thus on peer relationships in school, and on the length of their stay in Australia.

For David, language was the fi rst barrier to overcome at school: In my early school days, there were only three students from Taiwan in my class. All the others were ABC, or Chinese from Asia or Hong Kong who speak other dialects. They spoke Cantonese or other dialects which are unintelligible to most Taiwan migrants. Although I attended language school before I entered a formal school, I still fi nd it hard to adjust to learning my subjects in English.

Sandy, who immigrated at 10 years old, mixed with other Chinese since there were only one or two Taiwanese children in her class:

__________________

When I was small, I mixed with Chinese from China and Hong Kong, and my friends were mostly Asians … we belonged to the same group. When I grew older, I began to make the acquaintance of people of other racial groups in class; but I still hung around with Hong Kongers, or Chinese mainlanders after class.

Language played an important role, as David pointed out:

It depends on the level of your English. If you spoke good English, you would not be considered as an outsider. As they say, in this country eve-ryone is equal; but you are still differentiated by the amount of English you use.

Language skills played a key role in the self-identity of young migrants in schools. Their inability to communicate well in English led some young Taiwanese to seek out small groups in which they felt comfortable. However, this may have resulted in misunderstanding or discrimination on the part of the majority English speakers.

Mainly due to poor English-language skills, the young migrants got ac-quainted with other Chinese easily, with the exception of earlier arrivals. Over time, their social circles expanded, and they befriended members of other ethnic groups.30

Ethnicity was normally a non-issue for parents when it came to social activities and making friends.31 However, parents generally preferred their children to select boyfriends or girlfriends (and therefore potential spouses) who were of Taiwanese origin, or at least spoke Mandarin, and had a similar cultural background. Also, Taiwanese parents were more willing to accept an Australian son-in-law because traditionally daughters were to be married out.

Identity at the workplace

The workplace provided the young Taiwanese with opportunities to meet people from other ethnic groups, as most of them preferred not to work for Taiwanese companies. They were ready to blend into Australian society in other ways, beyond applying specialized skills and following professional practices.

Language played an important role in the young immigrants’ friendships with colleagues, and they still found it easier to communicate with people of Chinese origin, especially if they had known them in high school. By keep-ing a social distance from English speakers, the immigrants could not fully embrace the Australian culture. This pattern was found among immigrants from other nationalities as well:

__________________

30 Hsu and Ip, Gender Role and Self; Chiang and Liao, Back to base. 31 Chiang and Liao, Back to base.

Our company is like a United Nations. We come from Vietnam, Sri Lanka, the U.K., etc. We all speak English and get along well; but we all belong to our own circles, and keep our own culture. (Jason)

Like the young return migrants Chiang and Liao previously studied, most of the interviewees’ friends were from Taiwan, and they went back to Taiwan every year for a vacation or to visit their relatives.32 Most, however, claimed that they were both Australian and Taiwanese.

Other ways of expressing their identities were as “part Australian” and “part Taiwanese,” or “neither Australian, nor Taiwanese.” Steve, who had lived in Australia for 16 years, stated:

I think I am in the middle … I never watch news on Taiwan politics. … Australians expect you to discuss current affairs with them. If you express indifference, they ask: ‘Are you not interested because you are a for-eigner?’ The point is that they want to know if you care about Australia. I don’t really care about Taiwan, because I don’t live there, but my dad does. I know more about Australia because I grew up here.

There is no simple way of defi ning and expressing one’s identity, as it is complex and can change over time and space, due to a multicultural back-ground. Joshua spent 15 years in Melbourne:

We are people of different colours here. Even though we claim that we are not prejudiced against others, we actually all are. When you are Asian, you are a ‘visible minority’ no matter how long you stay in Australia. You are forever an Asian, no matter how you behave in the workplace. Three or four years ago, I said that I was Australian, and I had never said that I was Chinese, since I had never been to China. After visiting China, I feel that I identify more with Chinese culture. (Matty, health)

When treated differently or discriminated against in the workplace, the young respondents were reminded of their identity. They knew that they needed to work harder than Australians:

Racial prejudice is not serious in the place I work … Maybe it is not dis-crimination. They just want to look superior to you. (David, health) We are regarded as different by the wai guo ren (non-Chinese) here. They would like to see that you are doing better than they expect … but due to self-respect, they would not allow you to supersede them, even if they know that you are better. (Joshua, technical support)

__________________

Young Taiwanese felt even more like Asians in the workplace than they did at school. However, they did not identity with the Taiwanese community. They did not particularly look up to or become involved with Taiwanese organizations, which they perceived as “places of gossip,” “narrowly focused on their interests” and “too politically oriented.” Nevertheless, some were attracted by religious organizations, such as the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu-chi Foundation and various Christian churches that catered to the younger generation. In spite of their lengthy stay in Australia, many had accepted their parents’ values of fi lial piety and had kept up with Chinese customs such as ancestral worship and respect for older brothers and sisters. The lunar New Year was celebrated in the family, and ancestral worship was still practiced by some. It would appear that the Chinese culture that pre-vailed in one’s family or group of friends still had a signifi cant impact on the younger generation.

Conclusion: Becoming Australian

This study focuses on young fi rst-generation migrants from Taiwan living and working in Melbourne. These young people were either brought over by their parents or came to Australia by themselves to get a better educa-tion. As in other countries of East Asia, their children’s education played a critical role in the parents’ decision to immigrate to Australia. Studies have repeatedly shown that middle-class families in East Asia (including Taiwan and Hong Kong) provided their offspring with a Western education or an international experience by studying abroad for short or lengthy periods of time as a means of reproducing their social status. It has been argued that the acquisition of foreign educational credentials is conceived as part of a more general child-centred familial strategy of capital accumulation involving migration and transnational household arrangements.33 While young new-comers faced many problems in Australia, including language and school, social relationships, relationships with their families, and adjustment to the workplace, they had a tendency to accept the traditional values of their cultural origin. Within the framework of the Australian policy of multicultur-alism, their exposure to a global education and a variety of cultures enabled them to be competitive not only in Australia but also in Taiwan, China, Asia, and elsewhere in the world.

In another study of the “1.5 generation” in Australia, Hsu and Ip found that the majority of their informants identifi ed as unambiguously “Taiwanese,”

__________________

33 Johanna L. Waters, “Transnational family strategies and education in the contemporary Chinese

diaspora,” Global Networks, vol. 5, no. 2 (2005), p. 360. Johanna L. Waters, “Geographies of cultural capital: education, international migration and family strategies between Hong Kong and Canada,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 31 (2006), pp. 179-164.

with only a few seeing themselves as possessing a hyphenated identity,34 and even fewer considering themselves “Australian.”35 In contrast, our interview-ees commonly embraced “dual identities”; this may be due to long periods of residency and employment in Australia.Through our in-depth analysis of the “1.5 generation” of Taiwanese residing in Melbourne, we found that immigrants were capable of engaging in transnational ways of belonging to the host society, and that permanent settlement in Australia was most likely to take place in the future.

Like the young migrant returnees studied previously, the identities of the Taiwanese migrants we studied were embedded in the ways they selected their education and their employment pathways.36 They were likely to acquire an Australian identity because they had decided to pursue their careers in Australia instead of returning to Taiwan. We conclude that the identities of the “1.5 generation” are fl uid, fl exible and complex, and do not follow ethnic or racial boundaries.

This study may serve as a basis for future research. Members of the fi rst generation of young bilingual migrants are more cosmopolitan than their parents and have done much better in terms of employment, social adapta-tion and commitment to Australian citizenship. Rooted in Australia, they will, over time, contribute to the mainstream immigrant culture of their adopted country.

National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, March 2008

__________________

34 A hyphenated identity in the Australian case would mean that they became

Taiwanese-Chinese-Australian, similar to Hong Konger-Chinese-Australian. This would differentiate them from other Chinese (from Mainland China, Malaysia and Singapore, by the origin of their migration). See Hsu and Ip, Gender Role and Self.

35 The “1.5 generation” of Taiwanese migrants studied by Hsu and Ip ranges between 16 and

28 years of age (while our sample ranged from 23 to 30 years of age). The large majority was from Brisbane and not working full-time when they were interviewed. Taiwanese in Brisbane include more native Taiwanese than native Mainlanders, as they are originally from central and southern Taiwan. See Hsu and Ip, Gender Role and Self.