* In 1990, a totalof 22.3 million people of Hispanic origin lived in the US * Various Hispanic populations not

onlytend tolivein

differentregions of the US but are

differentin

educa-tional, occupa-tional,economic, cultural,and health

backgrmund

Cross-cultural

Medicine

A

Decade Later

Getting By

at

Home

Community-Based Long-term Care of Latino Elders

STEVEN P.WALLACE, PhD, andCHIN-YIN LEW-TING,PhD, Los Angeles, CalifomiaAlthough

evidence suggests that the morbidity and mortality of Latino elders(of

any Hispanicancestry)

are similar tothose

of non-Latino whites, Latinos have higher rates of disability. Little is known about influences on the use of in-homehealth

services designed to assist disabled Latino elders. We examine the effects of various cultural and structural factors on the use of visiting nurse, home health aide, and homemaker services. Data are from the Commonwealth FundCommission's

1988national

surveyof

2,299Latinos aged 65 and older.Mexican-American

elders are less likely than the averageLatino

to usein-home health services despite similar levels of need. Structural factors including insurance status areimportant

reasons, butacculturation is not pertinent. Physicians should not assume that Latino families are taking careof their disabled elders simply

because of a cultural preference. They should provide information and advice on the use ofin-home

health services when an older Latino patient is physically disabled.(Wallace SP, Lew-Ting CY: Getting by at home-Community-based long-term care of Latino elders, In Cross-cultural Medicine-A Decade Later [Special Issue]. WestJ Med 1992Sep;157:337-344)

M rs Martinezis an 81-year-old widow with dementia. HerAlzheimer's disease isnowatthe point where she has trouble bathing and dressing independently. Although

she lives alone, her daughter brings herin formedicalvisits and acts as atranslator. The daughter has mentioned thatat

leasttwoother familymembersalso visitMrsMartinez

regu-larly. Born inMexico, MrsMartinezis a permanent United States resident with Medicare and Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid program) benefits. Should a physician discuss long-termcareoptions with thefamily?

Long-term careservices existtocompensate forlost(or neverexisting) functional capacity.IYetfewpatients or

fami-liesknowabout therangeandavailability of servicesintheir communities.2 Long-termcareisoftenerroneously equated only with nursing home care. Physicians play a key role

becauseolderpatientsandtheir familiescommonly turnto

them forinformationand assistance.3

Variousfactors influence the interestandability ofLatino

families(ofanyHispanicancestry)toseek formallong-term

care. Most of the influences can beplaced intotwo broad

categories: culturalandstructural. Wefocuson

identifying

patternsofuseof

community-based

in-homelong-term

carehealth services by Latino elders. We compare the relative importance of cultural and structural factors associated with theuseofthose services and relate those

findings

toclinical practice.Theissueofin-homecaretakesonincreased

importance

when the future demographics of Latino communities are considered. First, the number of Latinos older than 65 is

projectedto increaseby500% by the year

203O.4

This willincrease the strainonthefamily andinformalresourcesthat

currently provide care. Second, that strain will be com-poundedby thedecliningsize offamilies ofminoritygroups, furtherreducing theavailabilityofinformalcare tothe

grow-ingnumber ofaged.

Health Status and Needs ofOlder Latinos

Wetypicallydiscussthehealthofminority populations in

referenceto those withthebest health status inthe United

States, usuallynon-Latino whites. Thestatusfor older Lati-nos is mixed, however. Compared with non-Latino whites, olderLatinos have better health indicators insomeareasand worse inothers.

A commonindicatorofthe healthstatusofpopulations is

deathrates.Unfortunately, ethnicity (Latinoversus

non-La-tino)is notreported byallstatesand is oftenmissingfor some statesthat do report it. From 1979to 1981, 13 of 15 states*

thatwere hometoabout45% of the Latino

population

pro-videdusable dataon Latinodeaths. Inthose states Latinos

aged 65 and older had lower death rates than older

non-Latino whites for almost all causes,especially diseasesofthe heart (athirdlower), chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

andallied conditions(50%

lower),

andmalignant

neoplasms (almost athirdlower).Higher

death rates occurredamong older Latinos for diabetes mellitus(twice

the non-Latinowhiterate); motorvehicle accidents(three-fourths

higher);

*Arizona,Colorado,Georgia,Hawaii,Illinois,Indiana,Kansas,Mississippi,

Ne-braska,NewYork,NorthDakota,Ohio,and Texasreporteddeathratesaccordingto

ethnicity.Califomia(which hasthelargestnumber of MexicanAmericans)and Florida (which has thelargestnumber ofCubans)didnotdifferentiate deathratesaccordingto

ethnicity.

FromtheDepartmentofCommunityHealthSciences,UniversityofCalifomia,LosAngeles,Schoolof Public Health. Presented in partatthe American Public Health Associationmeetings,Atlanta,Ga,November 1991.

This researchwassupportedbyfunds from the UCLA Academic Senate and computerresourcesprovidedbytheUCLA Office of AcademicComputing.

LONG-TERMCAREOFLATINOELDERS

ABBREVIATIONSUSED IN TEXT ADL=activities of daily living

IADL=instrumental activities ofdailyliving

nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis (two-thirds higher); and chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (two-thirds higher). The pattern for older Mexican Americans and PuertoRicanswassimilar,exceptthat deathratesforchronic liverdisease and cirrhosiswerehigher forPuerto Ricans and

the deathrates fordiabetes mellituswerebetween those of

Mexican Americans and non-Latino whites. The deathrates

of older Latinos average a fifth lower than those of

non-Latino whites, with the non-Latino mortality advantage greatest

amongoldermen.5More complete data for 1987-18states

including California-show similar results, with heart

dis-ease accounting for an even lower proportion of the total

number ofdeaths of older Latinos and malignant neoplasms accounting fora somewhat higher proportion.6

Morbidity patterns provide a similar variation in

inci-denceofdiseases. Formostmajordiseasesexceptdiabetes, Latinosappeartohave lowerratesofillness than non-Latino whites. Both age-adjusted and age-specific hypertension

ratesaresubstantiallylower forLatinos than for non-Latino

whites,' contributing toalower Latino prevalence of

coro-naryheartdisease and stroke.8 The overallage-adjusted

inci-dence of cancer in Latinos is also lower than that in

non-Latino whites (246versus335cases per100,000

popu-lation). Latinos have a lower incidence ofcancer of the

breast, lung, and colon-rectum. Therate isaboutthesame

forprostatecancer,and Latinos haveahigherrateof stomach

cancer.8Themostnotabledisease for which Latinosclearly haveahigher prevalence is diabetes.Self-reported diabetes is

twotothree timesmore commonamongMexicanAmericans

thanamongallwhites.The prevalenceofdiabetes increases withage,with22.7% ofMexican Americans aged 65to74 reporting diabetes9 versus 9.3% of all whites aged 65 and

older.10

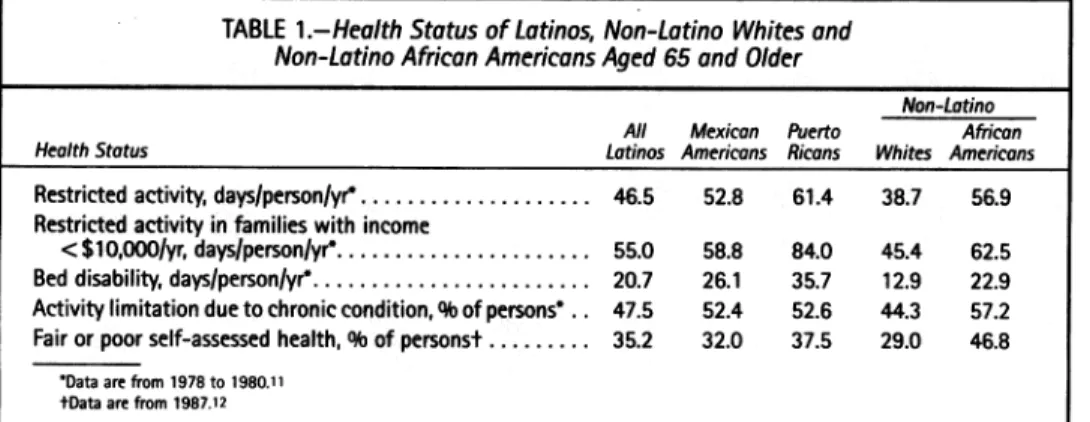

Although the death and diseasepatternsforolderLatinos

show several advantages over older whites, disability and

other health indicators are worse for older Latinos. Older

Latinosaveraged eightmoredaysofrestrictedactivityfrom

1978to 1980 than non-Latino whitesbuttenfewerdays than non-Latino blacks (Table 1). Puerto Rican elders reported

more restricted activity days than any group. Health status

declines withincome, buteven whenwelook onlyat

low-incomeelders, thepatternpersists. A more severe measure

ofdisability is the number of days that an older person is

confinedtobed

during

ayear.Thatmeasureshows that botholder PuertoRicans and Mexican Americanswere more

dis-abled than non-Latino African-American or white elders.

Therateofactivitylimitation duetochronicconditions for olderLatinoswasbetween that of older non-Latino African

Americans and whites. Themostcommonlyusedindicator of

general

healthstatusisself-assessed health. Table1showsthatmorethanathird of older Latinosreported their healthas

fairorpoor(versus goodorexcellent).This isslightly

higher

than theproportionof oldernon-Latino whites but

substan-tiallylower than theproportionofoldernon-Latino African Americans.

Our overallknowledgeofthe healthstatus ofLatino el-ders iscomplicated bydata inadequacies. In general older Latinos have better health than non-Latino whites in death

ratesandprevalences of certainlife-threateningchronic

dis-eases. The major disadvantages for older Latinos include

theirhigher prevalenceofdiabetes,theirgreateractivity

lim-itations,andtheirlowerglobal (self-assessed)healthstatus.

Because older Latinosare disadvantaged inactivity

limita-tions, examiningfactors thatinfluence theuseof

community-based

long-term

careisimportant.

Use of Health Care Services by Latino Elders

Althoughhealthstatusdataindicate the potential

impor-tanceofcommunity-basedin-home healthservices,mostof the researchonhealthcareusebyLatino elders has focused on theuse ofphysiciansand hospitals. In both areas older Latinos appear to receive similar or morecare than older

non-Latinos. Older Latinos havemore physician visits per

year than either non-Latino whites or African Americans

(Table 2).Thispatternholdsevenforthose reportingpoor or

fair health. Less variation occurs in the rates ofhospital admissions, althougholderLatinosareslightlymorelikely to use a hospital than older non-Latino whites or African

Americans.

Adifferentpatternemergeswhenwecontrolfor factors thatinfluence physician and hospitaluseamongmiddle-aged

and older Latinos. Puerto Ricans andMexican Americans

are morelikely than non-Latino whites orAfrican

Ameri-cans to see a physician as their physical activity becomes

limited,evenaftercontrolling forage, sex,healthstatus,and otherfactors. On the other hand PuertoRicans andMexican Americans are less likely tobe admitted to hospital when

theyrate their healthaspoor.13

Limited data existontheuseof long-termcareservicesby

Latino elders. Most data show that older Latinos are less

likely than either older whitesorAfricanAmericanstouse

TABLE 1.-HealthStatus ofLatinos,Non-Latino Whitesand Non-Latino AfricanAmericansAged65and Older

Non-Latino

All Mexican Puerto African HealthStatus Latinos Americans Ricans Whites Americans Restrictedactivity,

days/person/yr*

... 46.5 52.8 61.4 38.7 56.9Restricted activity in families with income

<$10,000/yr,days/person/yr*... 55.0 58.8 84.0 45.4 62.5

Beddisability,days/person/yr*... 20.7 26.1 35.7 12.9 22.9

Activity limitation duetochroniccondition,9bofpersons. . 47.5 52.4 52.6 44.3 57.2

Fairorpoorself-assessedhealth,9bofpersonst... .... 35.2 32.0 37.5 29.0 46.8

*Dataarefrom1978 to 1980.11

tDataarefrom1987.12

nursing homes,14,15evenafter other riskfactorsaretakeninto

account.16 The higher level of disability for Latinos in the communitymaybepartly because disabled Latinosremain in

thecommunity when similarly disabled whitesusenursing

homes.

In-home healthcareisviewedas analternativeto institu-tionalization, but we know little about the effects ofrace,

ethnicity, culture, and class ontheusepatterns of

commu-nity-based and informal long-termcareservices.17Older

La-tinosandnon-Hispanic whitesusepaidin-homecareinabout the sameproportions nationally, whereas older Latinos

re-ceivemoreinformalcare.'8This doesnot,however, control

forlevel ofdisability, availability of family, financialstatus,

orotherfactors that mightincreaseordecrease theneedfor formal and informalcare.

Astudy ofcase-managementclients in Arizona found that olderLatinoswerelesslikelytousecommunity-based

long-term care services than non-Latino whites despite their

greateractivitylimitations."9 The lower level of formal

sup-port received by Latino elders was balanced, however, by

higher levels of informalsupport. Greene and Monahan

cau-tionthat their datadonotindicate whetherthe familysupport

wasprovidedbecause formalsupportwasnotavailableorin

preferencetoformal services. This distinction between

ser-viceusepatternsas aresultof preferencesversusbarriers in

thestructureofthehealthcaresystemforms thecoreofthe

debateoverdifferencesin theuseofhealth servicesby

minor-ity elders.

Culture andInstitutionalStructure Influencing Health Care Use

Forces thatinfluence theuseof health services by

minor-ityelderscanbedivided intotwogeneral categories:cultural

and structural. Cultural influences include the belief

sys-tems,behaviors, and preferences ofa groupthat mightcause

certainpatternsofhealthcare use. Structural influences

in-cludethewaythehealthcaresystemand othersocial

institu-tions are organized and operated. They may present both

incentives andbarriers totheuse ofhealth services.

Culture. Cultural influences would beexpectedtoshape

theusepatternsoflong-term care,especially because

long-termcareofteninvolvesnontechnicalassistance thatcanbe

providedbyfamily members. Culturemayinfluence theuse

offamilyversuspaidcarethroughconceptsoffamily

respon-sibility and attitudes toward the useofpublic services for

those eligible for Medicaid. The strength and centrality of

familyare commonLatinovalues.'5 Apossible explanation

ofwhy Latinoeldersuse nursinghomes less often than do

non-Latinos is that Latino family roles make Latinos more

disposedthan non-Latinostomake the sacrificesnecessary tohelpolder relatives.20

Culturecanalso influence how satisfied patientsarewith their medicalcare.Healthcareprofessionals' lackof

knowl-edgeabout Latino culturalnormsandinabilityto

communi-cateinSpanishareoften citedasfactorsdiscouraging Latinos from seeking needed health care.21-23 Acculturation-an im-migrant's adoptionof attitudes andcommonbehaviors from

the dominantsociety-canaffect both familyfunctioning24 and health serviceuse.25It issurprising,therefore,that most

researchonhealthcare for Latino elders has notexpressly investigated the importance ofacculturation (others26 also

notethisdeficiency). Althoughacculturation doesnot

neces-sarily weaken Latino family functioning

overall,2"

there is evidence that acculturated families provide lower levels of informalsupport totheaged.28Thus,wemightexpectaccul-turatedLatino elderstouse moreformal services than

tradi-tional Latino elders.

Institutionalstructure. Incomeand health insuranceare

themostimportantstructuraldeterminants ofaperson's abil-ity to obtain health care. Older Latinos are

disproportion-atelypoorbecauseofthestructure ofouroccupationaland

economicsystem. Also,ourhealthcaresystemrations care

basedonabilitytopay. Almostall olderpeoplehave

insur-ance coverageforacutecare fromMedicare,but Medicare

paysless than 6% ofall long-term carecosts in the United

States.29

Giventheimportanceofincome and insurance in

deter-mining long-termcareuse,there isamajorgapinthe health

insurance statusofLatinoelders. Inthegeneralpopulation

many more Latinosareuninsured(33%)than whites(13%) orAfricanAmericans(19%).This islargelybecause Latinos

areconcentrated in industries suchaspersonal servicesand

construction that do not offer insurance and because they

disproportionately live in states-Texas and Florida-with

stringentMedicaideligibility criteria.30Asaresult, serious illness in thefamilyis consideredafinancialproblemalmost

twice asoften among Latinos asother whites (39% versus

19%).31

Retrospective Study

The following analysis reports on the use of in-home healthservices forallolder Latinos and for specific Latino

subgroups.Theiruseof services isexaminedby need,

indi-vidual characteristics, family status, acculturation, and health insurance.

Methods of Analysis

The datawerefromthe 1988 nationalsurveyofHispanics

aged65 and older sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund

Commissionon OlderPeopleLiving Alone. Telephone

in-terviews, doneprimarilyinSpanish, wereconducted of 937

MexicanAmericans, 714 CubanAmericans, 368 mainland

TABLE 2.-Use of HealthServices by Latinos, Nn-Latino Whites, and Non-Latino African AmericansAged65andOlder*

Non-Latino All Mexican Africon

Health Service Latinos Americans Whites Americons

No.ofphysicianvisits/person/yr... 8.2 9.1 6.3 6.7

No.of physician visits forthose withfairorpoorself-assessed

health/person/yr. 1.5 12.1 9.6 8.9

>1 Hospitalepisodes, %ofpersons .18.7 18.5 18.3 17.3

LONG-TERM CARE OF LATINO ELDERS

Puerto Ricans, and 280 other Hispanics.* The data were weighted to reflect US population estimates. The survey con-tractor's final report contains a complete methodologic

dis-32

cussion.

Wewereprimarily interested in explaining the previous year's use of in-home health services (home health nurse, home health aide, or homemaker). We focused on these ser-vices for two reasons. First, these serser-vices are often covered

byMedicaid, Medicare, or both, and target the most disabled

elders. Second, physicians arecentral to these services be-causephysiciancertification of need or a care plan is required

before Medicare or Medicaid will pay for them in many

situations. Evenwhen physician approval is not necessary, physicians can be an important source of referrals.

Explanatory variables include five health status indica-tors asevidence of need for in-home services: limitations in

activities of daily living (ADL)-bathing or showering,

dressing, transferring, walking, getting outside, using the

toilet; limitations in instrumental activities of daily living

*The largest nationality was Dominican (95 interviewees) followed by in decreasing frequency Spanish, Colombian, Salvadoran, Ecuadoran, Nicaraguan, and 15 other nationalities.

(IADL)-preparing own meals, managing money, using the

telephone, doing light housework,doing heavy housework; self-assessed health status; hospital admission within the past year; and frequent physicianvisits in the past year.

Demographic and social characteristics are often associ-ated withdifferences in the use of health services. We exam-ined the demographic variables of sex and age. Social level variables are subject to intervention and change. They in-cludeindicatorsoftraditional culture (acculturation),

educa-tion, social support(living alone, living withspouse,living

without spouse butwith or near children), income (poverty), and health insurance.

Two variables are frequently used to indicate levels of

acculturation: languageability21'33and agewhenthe

respon-dent arrivedon the USmainland.34 Wecreateda summary variable thatincludes both of these dimensionsand can be interpreted as the extent of acculturation of the respondent in

comparisontotheaveragelevelofacculturation (low)ofall

older Latinos.

Results

Needs and resources of Latino elders. The need for in-homehealthservices forolder Latinosappears tobe

substan-TABLE3.-Characteristics ofLatinos Aged 65and OlderbySubgroup'

All

Latino Mexican Puerto x2

Elders,t American, Cuban, Rican, Statistical

Charocteristic 4l 9b 4b * Significonce

Health

1 or moreADL difficulty ...

1 or moreIADLdifficulty...

Self-assessed health-fairorpoor...

Hospitalusepastyear...

Physicianuse > 12times pastyear...

Demographic

Women... Aged65-74yr...

Social

Immigratedatage55orolder...

Immigratedatage31-54 ...

Immigratedatage17-30 ...

Immigratedatage0-16...

Born in USlmainland ...

NoEnglish (monolingual Spanish)... Poor English§... Speaks English well...

<5yrschool...

6-11 yrschool...

Highschoolgraduateandup...

Livesalone... Lives withspouse...

Withoutspouse,lives withchildrenor

within 30min ... Family income Above poverty... Belowpoverty... Unknownorrefused... CoveredbyMedicare ... CoveredbyMedicaid...

ADL activities ofdaily living,IADL instrumental activities ofdaily

WeightedtoreflectUnitedStatespopulation estimates for oldi tlncludes "otherHispanics:'notpresented separately. *Significanceofx2comparisons amongthreesubgroupsisgiver

§Primary languageisSpanishandreportsfairorpoorEnglishat

39.1 39.6 32.0 44.6 .005 53.4 54.5 44.8 54.3 .005 53.3 57.0 46.7 62.7 .000 22.1 20.7 21.5 31.8 .001 23.9 20.5 28.8 36.7 .000 55.9 53.2 61.7 55.8 .019 62.1 62.3 54.7 69.5 .001 16.0 6.2 41.4 13.1 .000 21.2 10.6 49.8 40.4 12.1 12.4 5.3 34.2 12.4 17.9 3.0 12.3 38.4 52.9 0.5 0.0 39.4 33.8 57.3 37.4 .000 32.5 37.4 30.6 37.3 28.1 28.7 12.1 25.3 42.5 54.3 17.1 41.5 .000 38.7 33.8 49.1 45.1 18.7 12.0 33.8 13.4 22.4 22.3 23.1 26.2 >.05 48.7 50.0 44.6 46.5 >.05 36.6 38.1 33.5 35.6 >.05 31.9 29.8 37.6 30.5 .005 42.2 45.1 35.8 41.8 25.9 25.1 26.6 27.7 79.9 79.6 87.3 79.8 .007 42.2 39.0 52.8 50.7 .000 y living erLatinos. 340

tial but varies among the groups. In general older Puerto Ricans have the highestlevels ofneed,followed by Mexican

Americans and Cubans. Morethanathirdofall older

Lati-noshad one or moredifficulties inADLs, morethan half had

one or moredifficulties in IADLs, and more than half re-ported fair or poor health(Table 3). Morethantwofifths of all older Latinos hadahospitaladmission, andmorethantwo

fifthssaw aphysicianatleast 12 timesduring thepast year.

OlderPuertoRicans hadthe highestuseof medical services. The highADLand IADLdependencies, thelow self-assess-mentof health,andthecommon useof physician and hospital carereinforce the data presented earliershowingahigh need by Latino elders forcommunity-based long-termcare.

The olderLatino population includes more women than men,with most elders in the "young elderly" range (ages 65 to 74). The Cuban population had even more women and wereolder, reflectingtheir different history of migration to

theUnited States.35

Some social characteristics (Table 3) are liabilities for

those needing supportive services, including recent

immi-gration, limited English, low education, and poverty. Only

half of the Mexican-Americanelders and almost no Cuban or

Puerto Ricanelders reported being born in the United States. Asizable proportion, especially Cubans, immigrated at age

55andolder.Almost40%ofolder Latinosreportedspeaking

noEnglish, eventhough morethana quarter reported good

Englishskills. Almost half oftheolder Latinos had less than

aprimary schooleducation. Athird of olderCubans, how-ever,werehigh school graduates.Povertyisa common

prob-lem that ismost acuteamong Mexican-American elders. Resources fordisabled Latino elderspotentially include

health insurance and theavailability of family. Most older

Latinos live witha spouse orwithouta spouse but with or near (within 30 minutes of) their children. The living ar-rangementis theonlycharacteristicwhere there are no

statis-tically significant differences between the Latino subgroups. Althoughmostolder Latinos haveMedicare, the proportion

withoutcoverageis twice the nationalaverage.32On the other

hand older Latinos have high rates of Medicaid coverage,

partlyas aresultoftheirhighpoverty rates.

Mexican-Ameri-can elders, however, have the highest poverty rate and the

lowest Medicaid rate.

Characteristics of eachgroupreflect its immigrationand

occupational history. Older Mexican Americans are most

likelyto have been born in the United States but have had

limited occupational opportunities and have faced housing

discrimination.35 Among thisgroup, for example, 21%

re-ported farm work as their primary lifetime occupation.32 Thishistory explainswhyolderMexican Americans have the lowest educational levels, only average English abilities,

above-average

povertyrates, andincomplete Medicare cov-erage(Table 3).Inaddition,someolderMexican

Americans avoidgovernmentprograms, suchasMedicaid,and servicesbecausetheyareundocumented residents. In the1986

immi-gration legalization program,

1%

of Mexican immigrantsapplyingtoregularize theirstatus wereaged65orolder.36In contrast, olderCubans include manyprofessionals who

im-migratedasadults afterthe end of theCuban revolution in

1959.3' Consequently, Cuban elders have the most educa-tion, the least English ability,andoldestagesatthe timeof immigration. They can receive Medicaid because oftheir

special refugee status.38 Puerto Ricans are like Mexican Americansinmostsocialcharacteristics, althoughnoPuerto

Ricanelder in this survey was born on themainland. Puerto Ricans, however, are all US citizens as a function of the

commonwealthstatusofPuertoRico and thereforeneverface immigration status barriers to the receipt ofMedicaid.

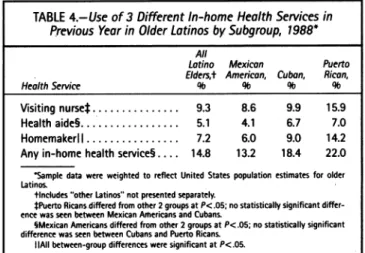

Useofservices.Given thehighlevels ofdisabilityamong the Latinoelders,weexpectedtofindhigh levels of service use. Table4shows thehighuseofcommunityservices,with somedifferences by subgroup.Visitingnurses werethemost commonly used in-home healthservice, followedby

home-makers andthen home health aides. Thehigheruseof most

in-home health services byolderPuertoRicans mirrors their higher levelsofdisability andpoorerhealth.

Mexican-Amer-ican eldersuse in-home health services less than Cuban

el-dersintwoof thethreeservices, but thislowerusedoesnot

reflectanyhealth status differences. It isimportant tonote

that each population is concentrated in different areas:

Puerto Ricans in New York City, Cubans in Florida, and Mexican Americans in the Southwest. Some of the

differ-encesinuse mayhave resulted from differences in the

avail-abilityofservicesinthe different areas.

Correlations show therelationshipsbetween theuseof

in-home healthservices and theneeds, individual characteris-tics, and social characteristics of each subgroup of Latino elders(Table 5). For correlations thatarestatistically

signifi-cant, we need to compare the size of the correlations to

determine the practical relevance. In particular, the

cor-relationsshow therelatively high importance of need factors

and Medicaidand therelatively lowimportanceof cultural factors.

Theneed indicators of ADL and IADLdisabilityhave the

largestcorrelations with theuseof in-home healthcare

(Ta-ble 5). Medical care use-hospital and frequent physician

care-has smaller butimportantcorrelations withtheuseof

in-home healthcare. Theonlyother correlations similarin

magnitude to theneed indicators are advanced ageand

re-ceiptofMedicaid. Smaller correlationsinclude thenegative relationship-decreases the chance of service

receipt-be-tweenlivingwithaspouseandin-home health services. For

Mexican-American and Puerto Rican elders, living alone

increases the chance that serviceswill be used.

Aswewouldexpect, ADLs, IADLs,andbeingadmitted

to a hospitalare each predictors of in-home health service

use. Part of the role ofvisiting nurses, homemakers, and

home health aides istoassist the disabledelderlywith ADLs

and IADLsorotherneeds thoseimpairmentsmightcreate.

TABLE4.-Use of 3 Different In-home Health Services in Previous Year in Older LatinosbySubgroup, 1988*

All

Lotino Mexican Puerto Elders,t Americon, Cubon, Rican,

HealthService 0lb 9l 0b 9lb

Visitingnursel... 9.3 8.6 9.9 15.9

Healthaide§... 5.1 4.1 6.7 7.0

Homemakerl ... .... 7.2 6.0 9.0 14.2

Anyin-homehealthservice§.... 14.8 13.2 18.4 22.0

Sampledata wereweightedtoreflect United Statespopulationestimates for older Latinos.

tincludes "otherLatinos"notpresented separately.

tPuertoRicansdifferedfrom other2groupsatP<.05;nostatistically significant

differ-ence was seenbetween MexicanAifericansandCubans.

SMexican Americansdiffered from other2groupsatP<.05;nostatistically significant differencewas seenbetween Cubans and Puerto Ricans.

Similarly, the pushtodischargethe elders fromhospitals as early as possible has moved some of the care formerly

pro-videdin the hospital into the home, increasing the need for

posthospitalnursing and other care.39 Further analysis, not

presented here, foundthatself-assessed health and physician visits did not predict the use of in-home health services after

controlling for other variables.40 Bothaglobal assessment of

healthas poor andfrequent physician visits can be the result

ofavariety of health conditionsnotrelated to a disability that requires long-term care. Consequently, older Latinos who use in-home care are more likely than non-in-home care users to see aphysician (the correlation), but physicianuse

itself doesnotincrease the use of in-home health services.

Mexican-American and Cuban men are somewhat less

likelytousein-home health services thanwomen (Table 5)

becausetheyaregenerallyyoungerthan thewomenand more

likelytobelivingwith a spouse. Gender by itself does not

influence theuse ofin-home health services.40 Frail older

TABLE

W-;tro

bh ealt5i~Os

by

AD',

Iy:.;:_mom)e L...:2uu8 .3

lAi. I( ormore.).27 .25 .33 .33 1 -fai -rpor,

60-eceto

rgood ....17 .18 .18 .12Hos0pita

admission ps y 0-nio,1-Yes .28 .25 .26 .23*-12

y... 13 .11 .11 .23 Sex-0female f male. -.08 -.11 -.12 .09t Age, r0-i65-7441 75.7 .23 .24 .24 .24 Accultuaion.V...C.-.04. -.01± -.05± -.10± Educatlion- <6 yr 6Allyr,12yrandup . -.05 -.03± --.06± -~.18Liv aWene-O-no, I-yes. 12A .17 .02± .15

Liewt

puse--0=o,1-yf-es... ~-.11 --.09 --.13 --.15

Live witout spouse and

0-no yes.0.±...17 .02± .02±

FmilpvryQ-o1ys .09 .10 .01± .19

§Mdicare-.0 0-n =yes.fI ** 09 .-.07± .00 .16

:edaid-Q-no,1=y1es ...20 .17 .19 .17

M)-clisof dail living,IADL=~instumntlactvitesofdailiving Smpl dataiewited withthenl00o08ied

tAli 0ltnarevigniflcantat.t:000 P<05e.n.tstatistical2etOsew which ar y

;significant - 7. 23 24 .4 2

Latinos (age 75 andolder) are morelikelyto usein-home

services independent of need and social factors.40Agemay

increase the number and severity of disabilities (we only

measured theirpresence) or weaken informal support(for

instance,anagingspouse may nolonger bephysically ableto

provide thesamelevel of assistance), orboth.

Asweexpected, wealsofound correlations between

in-homehealthcare useandsomeof the socialresources.

Liv-ing alone, which indicatesalower level ofavailablesupport,

increases the chance ofusing in-home health services for

mostsubgroups.Accessibilitytofamily help,asindicatedby

living with a spouse, reduces the use of in-home services.

When other variables arecontrolled, living without a spouse but with or near childrenalso reduces the use of in-home healthservices.40 What the data do not show is the causal order-whether family is used in preference to formal

ser-vicesorbecause formal servicesareunknown orunavailable.

Latinoelders with Medicaidcoverage are morelikely to use services,* demonstrating the importance of financial barri-ers to in-home service use. Medicaidcan pay for in-home

health services, reducing the financial burden for low-in-comeLatino elders.

The small and not statistically significant correlations

withsome variables are asimportantasthe larger correla-tionsjust described. Inparticular, acculturationhas an

unex-pectedlysmall or notsignificant correlation withthe use of

in-home health services (Table 5). Similarly, despitethe

em-phasisonfamily in Latino culture, the accessibility of

chil-dren for those living without a spouse had no statistically significant correlation with the use of in-home health

ser-vices. Acculturation, whichwasmeasuredby knowledge of English and age atimmigration, hadnorelevant correlation within-home health serviceuse. Evenwhencontrolling for othervariables, acculturation remainednotsignificant.

Sim-ilarly, graduation from high school hadnoindependent effect

on the use of in-home services.40 The lack of any overall

acculturation effectsupportsthe conclusion thatfamily sup-portisnotprimarily aresult ofastrongculturalpreference for family help. Cuban elders had few significant correla-tions of socialcharacteristics with serviceuse.

Aftercontrolling for all the other variables,PuertoRican eldersarestill twiceaslikelyto usein-homehealthservices

astheother Latinogroups.40 This is possibly because older

PuertoRicanscommonlylive in New YorkCity, which hasa

relatively well-developednetworkof in-home services com-pared with otherparts of the country (V. Levy, New York

City Department for the

Aging,

oralcommunication,

No-vember 1991). Similarly, Mexican-American elders may

have lower in-home health serviceusebecausesomelivein

nonurbanareasandin states where fewer services exist.

Summary

Latinoelderscompriseadiversesetofsubgroups.t Our data showthat allsubgroupsfrequently have functional

limi-tationsand low health status, with PuertoRicanshaving the

worsthealth. Acculturation has littleor noeffectontheuseof in-home healthservicesfor anysubgroup, whereas structural factorssuchashealth insurance andthe localavailability of services have a moderate effect on all subgroups. These structural factors are the most likely reasonthat

Mexican-American elders use in-home health services less than the othersubgroups.

StructureorCulture-WhatDoesIt Matter?

Inanidealhealthcaresystem,theuseofservices would

bedeterminedonly byneed andpersonal preferences. Our datashowthat needfactorsareamongthe strongest predic-tors oftheuse of in-homehealth services. Weconsistently

*The increased chance of usebythose in poverty ismostlycausedbythose in povertybeingmorelikelytohaveMedicaid,tolivealone,and tohave ADL or IADL

limitations,each of whichindependentlyincreases the use of in-home health services.

tTherewere notenoughCentral Americans in thesampletoform any

generaliza-tions,butthoselivinginthe Southwestprobablyhave many characteristics similar to Mexican-American elders: asignificantproportion willbe undocumentedresidents,

and mostwill have lowincomes,lowMedicaid coverage, and low in-home health service use. Few will have been bom in the United States.41

found,

however,

that health insurance status andliving

ar-rangements alsoinfluence theuseof in-homehealth services.

Ifwe are to ensure that Latino elders receive appropriate

health

services,

we need tounderstand the extent to whichstructural andcultural forces arealsoinvolved intheuseof services.

The

importance

ofliving arrangements-especially

after otherfactors aretaken into account-could bedescribed asthe result ofacultural

preference

forfamily help

inplace

of formal assistance. Acculturation has nosignificant

effect,however,

which contradicts theinterpretation

that relianceonfamily

inplace

offormal in-home health services isasimple

cultural

preference.

Themorelikely explanation

isthat fami-lies coulduseandbenefit from theextrahelp provided by

in-home health care,regardless

of their cultural orientation. Latinoelders,

theirfamilies,

and all otherelders, however,

generally

havealowawarenessoftheexistence and purpose of in-home health services.2"3 Their low-incomeback-grounds

make them lesslikely

to think that paid help is feasible.A moderate use of

physician

services did notindepen-dently

increase older Latinos' use ofin-home healthser-vices,

despite

the fact that thephysicians

are the mostcommon sourceof information about

long-term

care inthegeneral population.3

Ifmostphysicians

assessedthe disabili-ties of the older Latinopatients they

see often and made referralstoin-home health services when indicatedby need,wewould expectto see

physician

visitsindependently

associ-ated with increased serviceuse.One reason

physician

visits may not increase in-home health servicesuseisthat manyphysicians

mayobserve thefamily providing

in-home assistance and assumethat such assistance isprovided

for cultural reasons. It is possible,however,

that thefamily

assistance isprovided

because the elder and thefamily

are notaware ofthe range ofoptions

availableoraredeterred

by

thecomplexity

of thelong-term

caresystem and itsfinancing.

Families may also think that because caregiving

has not yet become acrisis,

it is notappropriate

toask for additionalhelp.

ForLatino elders who have Medicaid and therefore access to a case manager, it would behelpful

forphysicians

to assessthefunctionaldis-ability

level oftheirpatients

andcounsel their disabled older Latinopatients

about the range ofcommunity

services availa-ble tosupplement

the carethey

mayalready

be receiving from theirfamilies. Researchonthegeneral

olderpopulation finds that formalservicescomplement

rather thanreplace

the efforts offamily.42

Older Latinos often holdexpectations

of assistance from theirfamilies,2"

43butthoseexpectations

donotmeanthat formal services wouldnot

improve

thestatusofthe eldersandtheircare

givers

orthatin-home health carewould be refused if offered.

For Mrs Martinez

(opening

paragraph),

thephysician

should discuss the

availability

ofMedicaid and otherhome-makerservicesas an

option

forproviding

someofthebasiccarethat she needs.Ahomemaker could

help

MrsMartinez get up,bathe,

anddressinthemorning,

thereby allowing

thefamily

tocontinueproviding

otherADL, IADL,

andemo-tional support. Because the

steadily deteriorating

nature of Mrs Martinez'sdementia willplace increasing

demandsonher

family

supportsystem,the formal assistancemight help

preventthefamilysupportfrombecoming prematurely

over-whelmed.

Weshouldalsonot

ignore

theroleofculture in thecareofLatinoelders. Attention to cultural values such as respect,

the involvement of family members inhealth decisions, and

use of the Spanish language have beenshown to beimportant

aspects of thequalityof care forLatinos.21'44'45 Attentionto

culture should notdiverthealth careprofessionals from en-suring that older Latinos have theopportunity toreceive in-home health services when their physical conditionmerits it.

For Mexican-American elders especially, who facethe most

structural barriers tothe receipt ofcare, physicians should

make an effort to ensure access to needed visiting nurse, home health aide, and homemaker services.

REFERENCES

1. KaneRA, Kane RL: Long-TermCare:Principles,Programs, and Policies. New York, NY, Springer, 1987

2. Holmes D, Teresa J, Holmes M: Differences among black, Hispanic, andwhite people in knowledge about long-term care services. Health Care Financ Rev 1983;

5:51-67

3. Local Information on Long-Term Care: Consumers' and Providers' Points of

View. Washington,DC, Health Advocacy Services Section, American Association of RetiredPersons, 1991

4. US Senate Special Committee on Aging: Aging America: Trends and Projec-tions.Washington DC,GovernmentPrinting Office, 1989

5. Mauren JD, Rosenberg HM, Keemer JB: Deaths of Hispanic origin, 15 report-ing states, 1979-1981. VitalHealth Stat[201 1990; (18):1-73

6. National Centerfor Health Statistics: Advance report of finalmortality statis-tics, 1987. MonthlyVital Stat Rep 1989; 38(5 suppl)

7. Pappas G, Gergen PJ, Carroll M: Hypertension prevalence and the status of awareness, treatment,and control in theHispanic HealthandNutrition Examination Survey(HHANES) 1982-1984. Am J Public Health 1991; 80:1431-1436

8. Report of the Secretary's Task Force on Black andMinorityHealth.Washington,

DC, US Dept of Health and HumanServices (DHHS), 1985

9. Perez-Stable EJ, McMillen MM, Harris MI, et al: Self-reported diabetes in Mexican-Americans: HHANES 1982-1984. Am J Public Health 1989; 79:770-772

10. Ries PW: Health of black and white Americans, 1985-1987.Vital Health Stat

[1011990; (171):1-114

11. Trevino FM, MossAJ:Healthindicators for Hispanic, black, and white Amer-icans.Vital Health Stat [101 1984; (148):1-88

12. RiesPW:Americans assess their health: United States, 1987. Vital Health Stat [10] 1990;(174):1-63

13. Wolinsky FD, Benigno EA, Fann U, et al: Ethnic differences in the demand for physician and hospitalutilization among older adults in major cities: Conspicuous evidence of considerable inequalities. Milbank Q 1990; 67:412-449

14. Sirrocco A: Nursing home characteristics: 1986 Inventory of long-term care places.Vital Health Stat [14] 1989; (33):1-32

15. Wallace SP, Facio EL: Moving beyond familism: Potential contributions of gerontologicaltheory to studies of Chicano/Latino aging. J Aging Stud 1987; 1:333-354

16. Greene VL, OndrichJI: Risk factors for nursing home admissions and exits: A discrete-time hazard function approach. J Gerontol Soc Sci 1990; 45:S250-258

17. Antonucci TC, Cantor MH:Strengtheningthe family support system for older minoritypersons,InJackson JS (Ed): Minority Elderly: Longevity, Economics, and Health.Washington, DC, Gerontological Society of America, 1991, pp 32-37

18. Hing E: Long-Term Care Use By Black and White Elderly. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, New York City, October 1990

19. Greene VL, Monahan DJ:Comparative utilizationof community based long term care services by Hispanic and Anglo elderly in a case management system. J Gerontol 1984;39:730-735

20. Morrison BJ: Sociocultural dimensions: Nursing homes and the minority aged, In Getzel GS, Mellor MJ (Eds): Gerontological Social Work Practice in Long-term Care. New York, NY, Haworth Press, 1983, pp127-145

21. Valle R, Mondoza L: The Elder Latino. San Diego,Calif,Campanile Press, 1978

22. Lacayo CG: A National Study to Assess the Service Needs of the Hispanic Elderly. Los Angeles,Calif,Asociacion Nacional Pro Personas Mayores, 1980

23. Berkowitz SG: Assessing the Unmet Service Needs of Elderly Homebound Blacks, Hispanics, and Vietnamese in Arlington: Recommendations for Improving Delivery and Overcoming Barriers to Utilization, FinalReport. Washington, DC, Gerontological Society of America Technical Assistance Program, 1989

24. Becerra RM: The Mexican-American-Aging in a changing culture, In McNeely RL, Colen JN(Eds): Aging in Minority Groups. Beverly Hills,Calif,Sage, 1983, pp108-1 18

25. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL,BumamMA, Karno M: Acculturation and the probability of use of health services by Mexican Americans. Health Serv Res 1989; 24:237-257

26. HarelZ, McKinney EA, Williams M: Aging, ethnicity and services: Empirical and theoretical perspectives,InGelfand DE, Barresi CM (Eds): Ethnic Dimensions of Aging. New York, NY,Springer, 1987, pp 196-2 10

27. Keefe SE, Padilla AM:Chicano Ethnicity. Albuquerque, NM, University of New MexicoPress, 1987

28. Lubben JE, Becerra RM: Social support among black, Mexican, and Chinese elderly, In Gelfand DE, Barresi CM (Eds): Ethnic Dimensions of Aging. New York, NY,Springer, 1987, pp 130-144

LONG-TERM CARE OFLATINOELDERS

29. Policy Choices for Long-term Care. Washington, DC, US Congressional Bud-getOffice, 1991

30. HispanicAccess toHealth Care:SignificantGaps Exist. Testimony before the HouseSelect Committee onAging and theCongressional HispanicCaucus, publica-tion GAO/T-PEMD-91-13.Washington, DC, General Accounting Office, 1991

31. Anderson RM, Giachello AL, Aday LA: AccessofHispanics to health care and cutsin services: A state-of-the-art review. Public HealthRep1986; 101:238-252

32. A Survey of Elderly Hispanics, Final Report-Conducted for the Common-wealth Fund Commission on Elderly People Living Alone. Rockville,Md, Westat,

1989

33. Cuellar 1, Harris LC, Jasso R: An acculturation scale for Mexican American normaland clinicalpopulations. Hispanic J Behav Sci1980;2:199-217

34. Zuniga-Martines M: Los Ancianos: A Study of the Attitudes of Mexican AmericansRegarding Support for the Elderly(Dissertation). Waltham, Mass, Bran-deisUniversity, 1980

35. Portes A, Bach R: Latin Journey. Berkeley,Calif, Universityof California Press, 1986

36. US Immigration and Naturalization Service: ProvisionalLegalization

Applica-tionStatistics, Dec1,1991.Washington, DC, StatisticsDivision,Office of Plans and Analyses, 1991

37. Queralt M: The elderly of Cuban origin, In McNeely RL, Colen JN (Eds): Aging in MinorityGroups. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1983, pp 50-65

38. Pedraza-BaileyS: Political and Economic Migrants in America: Cubans and Mexicans. Austin, Tex, University of TexasPress, 1985

39. Morrisey MA, Sloan FA, Valvona J: Shifting Medicare patients out of the hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 1988; 7:52-64

40. WallaceSP, Lew-Ting CY: Formal Service Use and Family Support of Latino Elderly. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Atlanta, Ga, October 1991

41. Wallace SP: The new urban Latinos: Central Americans in a Mexican immi-grantenvironment. Urban AffQ 1989; 25:239-264

42. Noelker LS, Poulshock SW: TheEffects on Families of Caring for Impaired Elderly in Residence. Washington, DC, US DHHS, Administration on Aging, 1982

43. MarkidesKS, Martin HW, Gomez E: Older Mexican Americans. Austin, Tex, University of Texas Press, 1983

44. Cuellar JB:Hispanic Americanaging: Geriatric education curriculum devel-opmentfor selectedhealth professionals, In Harper MS (Ed): Minority Aging. Wash-ington, DC, US DHHS, Health ResourcesAdministration,1990, pp 365-413

45. ApplewhiteSR,Daley JM: Cross-cultural understanding for social work prac-tice with the elderly, chap 1, InApplewhite SR (Ed): Hispanic Elderly in Transition. New York, NY, Greenwood Press, 1988, pp 3-16

* * *

IN

APRIL, HEARING THE NEWS

it's beforebeing

ahostageto

lossanddying numbsandeach

word ischarged

andwhen my mother tells me I'mso

prettyasI see

her sit down

inSearslooking lost then looks

upatme and

waves asshe does

from the other

twin bed whenI can'ttellsince

she often sleeps with hereyes open ifshe's sleepingand I wasn'tdrained fromstaying 11 weeks in ahouse that's acageis fullof cages as mysister tries to jail everything

thatshouldbreathe

before thenight

mare ofliving inahouse in

enemyterritory wastheprice

forhaving

her still

LYN LIFSHIN©)

Niskayuna,NewYork 344