現代奧運發展的反思

國立臺灣教育大學

李炳昭

中文摘要

本文旨在探討現代奧運發展所帶來的部份議題。其中,進行分析的議題包括現代奧運與 古代奧運的變遷差異,商業化以及專業化的論辯,期能以此提供現代奧運發展另一思考 空間。本文最末提出,近年來所謂「現代」奧運發展機制已經和古希臘時代及古柏坦公 爵所持的「傳統」初衷,大相逕庭。 關鍵詞:現代奧運、商業化、專業化Critical Reflection on Some Issues

of the Modern Olympic Games

Introduction

Over the last hundred years, there have been numerous changes and advances in the areas of technology, communications, transport, global communication, and awareness, medicine and drugs, doping and ergonomics, sports training methods, sports equipment and facilities, and the evolution of scientific and technological research on sports. Having coincided with such development, the modern Olympic Games are always a key focus owing to their symbolic manifestation of modern sports. Indeed, the Olympic Games is a multi-sporting event, a mass media spectacle with global audiences on earth bringing together people from different continents, with different cultural backgrounds, religious beliefs, and national characteristics (Chatziefstathiou, 2004). There is no doubt that the modern Olympic Games have been an enormous success with growth in the number of participants, intensified media awareness, boosted economies, improved levels of achievement and so on (Vigor, Mean & Tims, 2004). However, there is good reason to wonder at this growth not least in the light of the parallel growth of destructive forces that have caused considerable erosion of Olympic ideas (Moller, 2004). In particular, following the huge profit made by Olympic Games in 1984, critical issues have further raised to argue what is Olympism, what is the spirit of the Olympic Games (Bale & Christensen, 2004) since they are moving away from Coubertin’s orientation one century ago.

Within in this context, this article reports the above arguments based on documents published by the International Olympic Academy (IOA) in Greece since the IOA constitutes the intellectual expression of the Olympic Movement, which represents one of the finest aspects of the universal intellectual tradition (NIKOLAOU, 2003). Additionally, a conduction of providing perceptions of academics in Olympic study will help to comment upon the

developing process of the Olympic Games as well as to triangulate with materials collected from the IOA. By doing this, this article seeks to highlight some important issues in relation to the modern Olympic Games. Such issues comprise the difference between the ancient Games and the modern Olympic Games, commercialization, and professionalism which have manifested the development of such a world-sport-festival. As the Olympic Games remain a Western-dominated movement, both in terms of political power and the origin of sports on the program (Guttmann, 1994), critical arguments in relation to development of such Games are clearly Eurocentric and North America centric. Having done this article, the author’s viewpoint attempts to represent non-Western voice, more specifically, a Taiwanese voice, which is typically under-represented in international academic debates about the future of the Olympic Games.

Methods

A major attempt of this article is made to synthesize this evidence to generate a framework for an examination of development of the Modern Olympic Games, reviewing of documentary material published by the International Olympic Academy in Greece. The documentary-based element mainly takes the form of qualitative content analysis, which was applied to the official reports of various sessions held by the IOA. In addition, critical literature in the form of analysis of a number of academic papers, which trace and explain the development of the Olympic Games, was also employed to conduct this study. Finally, the computer software Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching Theorizing (NUD*IST) was employed to help code/categorize the gathering data and subsequently contributes to the analysis of data.

Discussion

A. Spiritual and Ritual Difference between the Ancient Olympic

Games and the Modern Olympic Games

The first phases of the Olympic Games were associated with the gradual development of its cultural basis expressed by religious means (Georgiadis, 2003). This period is significant from a historical point of view, but the religious context of ancient athletics, for obvious reasons, has no deeper consequences for modern times- at a certain stage ancient religion simply ceased to meet human needs (Henry, 2002; Liponski, 1995: 72). The power of relevant ceremonies is enhanced by their quasi-religious character. Pierre De Coubertin consciously borrowed from Catholic ritual to invest Olympic ceremonies with religious quality (Baker, 2000). He had sought to make the Olympic Games a ceremonial affair and envisioned the modern Games as an aesthetic and spiritual festival. Indeed, the ancient Games emphasized religious orientation, a manifestation of ritual (Parry & Girginov, 2005). Toomey and King (1984: 87) have supportably stated that “in Coubertin’s view, Olympism was a classical religion.” In the same vein, Melik-Chakhnazarov have also argued that,

The idea itself of establishing athletic contests in ancient Greece was closely linked to the imperative need for peace. Or rather, it was the wish to contribute, in an effective way, to the consolidation of peace in the Peloponnese that led the people to erect an obstacle to war in the form of truth (Melik-Chakhnazarov, 1998: 175).

In this concept, the ancient Greeks tried to constitute a major factor of peace and stability by the games rather competitions between cities. Contradiction between ideals and reality is probably the most permanent feature of the modern Olympic Movement. It should be noted at this point that contrary to the ancient Greek Olympic Games whose character was religious (Georgiadis, 2003), the modern Games are a purely athletic event, aiming at the

promotion of peace and friendly competition among participating athletes and nations (Muller, 2004). Although concept of ‘peace and friendship’ is seen and promoted nowadays, the winning competitions are largely emphasized by the media, international corporations etc. which evidently represent the interests of Commercial ones instead of religious parts.

Further, there are symbolic changes, for example, olive wreaths have been replaced by medals; Hymns praising individual winners have replaced by the anthems of the winners’ countries (Tames, 1996). Indeed, the last quarter of the 19th century was recognized as a major phase in “international spread of sport, the establishment of international sports organizations, the growth of competition between national teams, the worldwide acceptance of rules governing specific sport forms and the establishment of global competitions such as Olympic Games” (Maguire, 1999). People, today, are interested in athlete’s performance and record since more and more professional players attend world sports events. Winning a swag of medals and breaking records has almost become the priority for athletes (Cashman, 2004). With involvement of commercial groups and dramatic development of media, the modern Olympic Games and athlete’s view have also been influenced in order to meet needs of people, surely the benefits of commerce, marketing, media as well (Parry and Girginov, 2005). Sport, in current times, seems to be seen as an ‘entertainment’ by watching athlete’s performance and such a shift is completely different from the fact that “The Olympics could foster an adaptation of fruitful past principles…and in the prime of athletes’ manhood to learn in the chivalrous and friendly rivalry of athletic contests that mutual respect and esteem, which are the only sure basis of International concord” (Tomlinson, 2005: 51). In particular, “the athletic contests in ancient Greece, during their period, were the primary instrument of education and training” (Yalouris, 2001: 74). In this sense, the Olympics and the very grandeur of the scale of the conception of De Coubertin, that constitutes a project of seriously globalizing proportion and potential, ridden with contradictions rooted in De Coubertin’s aristocratic, imperialist, patriarchal roots (Tomlinson, 2005).

B. Commercialization

The relationship between sport and business has significantly changed over the past twenty years. The increased amount of resources provided to sports by private sectors has greatly contributed to making sport big business and there are no sport games bigger than the Olympic Games worldwide. Commercialized sport has become commodified in the past two decades, especially with the arrival of specialized sports television channels who have paid much greater sums for the broadcasting rights than previously (Foster, 2005, see Table 1). In general, the Olympic Games have become a multi-million dollar business system with globalization, marketing, sponsorship, and commercialization paramount (Chappelet & Bayle, 2005). The reciprocal occurrence of ‘The Olympic Partners’ (TOP) program between the IOC and international corporations could be the best example for articulating such phenomenon (see Table 2). Meanwhile, “the sponsor companies recognized that sporting the Olympic Movement with communications that enhance the image is in everyone’s best interests” (Payne, 1998: 62). The idea that multinational corporations have recognized the immense worldwide potential of being associated with the Olympic Movement and are willing to pay “in excess of 50 million dollars for the right to be associated with the Top Program” (Schrettle, 2000: 304) has helped to explain the above claim. Although the underlying philosophy of Olympic marketing is to enhance the enduring and valuable image of the Olympic Movement (Girginov & Parry, 2005: 110), the commercialization of the Olympic Games might result in a dilemma between the spirit of Olympism and the IOC’s concern for the opening of marketing was to ensure the continuity of the Games and to create some reserve funds.

Table 1 Global TV Revenue for Olympics, 1980-2008 Summer Games Revenue

(Million US$)

Winter Games Revenue (Million US$) 1980 Moscow 101 1980 Lake Placid 21 1984 Los Angeles 287 1984 Sarajevo 103

1988 Seoul 403 1988 Calgary 325

1992 Barcelona 636 1992 Albertville 292 1996 Atlanta 895 1994 Lillehammer 353 2000 Sydney 1318 2002 Salt Lake City 748

2004 Athens 1482 2006 Turin 832

2008 Beijing 1697

Source: IOC Olympic Marketing Fact File, No.45, 1999, 2000 (Girginov & Parry, 2005: 110)

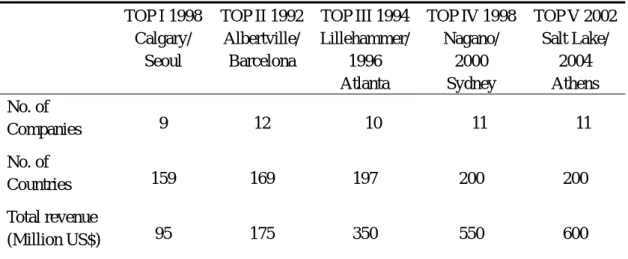

Table 2 Stages of Evolution of the TOP Program TOP I 1998 Calgary/ Seoul TOP II 1992 Albertville/ Barcelona TOP III 1994 Lillehammer/ 1996 Atlanta TOP IV 1998 Nagano/ 2000 Sydney TOP V 2002 Salt Lake/ 2004 Athens No. of Companies 9 12 10 11 11 No. of Countries 159 169 197 200 200 Total revenue (Million US$) 95 175 350 550 600

Source: IOC Olympic Marketing Fact File, Nos. 60, 65, 1999, 2000 (Girginov & Parry, 2005: 111)

As have already noted, a major concern of the Olympic Movement has been the influence or challenged of the critical issue with commercialism, since the huge commercial profit was made in the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Indeed, through the intervention of television and steadily advancing commercialization since the 1980s, “the Olympics have become a very lucrative event involving commercial contracts and the high-scale profits”

(Chatziefstathiou, 2004: 22). Further, it is believed that there is a real threat to the Olympic Movement from aggressive and non- sensitive sponsors. In fact the Olympic Movement, the sponsors and marketers wish to reach, in a positive way, the largest audience possible. In contrast, with sponsors and marketers which deal with materialism and act for profit, the Olympic Movement deals with ideals, and with education (Parry & Girginov, 2005; Muller, 2004). The consumerist values of commerce seem to be in contradiction to the more ethical qualities of the Movement. Sponsors are interested in countries, which offer a wide and solid market for their products. This could hamper possibility of acting as the host of an Olympic festival. The United States has hosted four summer and four winter Games as well. As so far, no Olympic Games have been held in an African, or a Latin American, or a Middle East city. Even though infrastructures are improving in those world areas, they may, in reality, be falling further and further behind in meeting increasingly high standards set for hosting the great festival. Should the IOC set aside resources to support a guarantee that “the Olympic Games will be celebrated from time to time in areas of the world that can only dream of ever serving as host” (Barney, 1994: 130). Ironically, this has led a controversy while the IOC insisting on its universalism in current world.

The Olympic Games is such “a strong brand name that companies in thousands are willing to pay large sums of money for the right to exploit” (Moller, 2004: 204-205). In accepting financial benefits proffered by commercialism, the IOC has had to accept inevitable change which has been reflected throughout the whole of the Olympic Movement. The Olympics just operate as “a giant billboard for the elite crop of multi-national corporations that are the preferred sponsorships partners of the International Olympic Committee” (Tomlinson, 2005: 49). The concern here is expressed as to whether the IOC has complete control over sponsors or whether corporate money is able to diminish the ethics of the Movement. The IOC has to question whether commercial interests over shadow the correct image of the Olympic Movement. Though the important values that the Olympic Movement

ought to always remember that sport, not commercial interests, should control its destiny, one wonders whether the IOC operates in this way, particularly, when a number of corruption/scandals have disclosed (Chatziefstathiou, 2004).

C. Professionalism

For more than five decades, the Olympic Movement consisted of different types of ideals, in which participation was more important than winning and that sport was an inherently valuable activity that offered important benefits to participants (Whitson, 1997). Besides to this point, concepts related to value of athletes should be gentlemen and only amateurs were allowed to compete in the Olympic Games which were also highly promoted by Pierre de Coubertin. However, the change of the ‘excluding’ amateurism requirements from the Olympic Charter in the 1970s has allowed professional participation in international sport in which the appearance of the USA basketball ‘Dream Team’ in 1992 Barcelona’s Olympic Game could be best exemplified. Elite sport has thus become a global norm as the Olympics have become big business and audiences everywhere have become accustomed to the norms and values of professionalism (Donnelly, 1996). And, in a whole succession of sports professionalism has gradually pushed amateur competitions and organizations into the background (Whitson, 1997).The transformation from amateurism to professionalism in sport arena can be deemed as making a living from sport or a standard in order to bring out the athlete’s best performance and competence. Professionalism, therefore, structures the culture of elite sport under whatever auspices it is conducted and these transformations in the culture of the Olympics coincide with the Olympic Movement’s embrace of commercial sponsorship and so on. Thus, a particular feature of the commercialization of sport is the professionalization of the athletes themselves, “brought about by the increased flow of money into sport and the consequently enhanced market value of athletes” (Toohey & Veal, 2000).

contract and take part in competitions. The more successful they are, the more money they earn”. The true amateur spirit of fair play and friendship, was not always seen either despite that the Olympism still insists on it. Today eligibility for the games has moved away from the spirit of amateurism. In many of the Olympic sports, “the incentives to win are now so great that playfulness, enjoyment of the body, and sportsmanship are giving way to work rate, discipline, and tactical” (Whitson, 1997: 3). Therefore, we can see that one of the major changes has been the advent of the professional athlete. The status of the athletes who participate in the Olympic Games is constantly changing, ranging from the bourgeois or military to the professional athlete. Professional athletes, who train full time, have replaced amateur athletes. Olympic sports have thus become more professional (Powell, 1999). This might be a factor that the IOC allows more and more professional players to participate in the Olympic Games in order to attract the global audiences and sponsors’ participation and attention. This tendency, more or less, seems to be consistent with the concept of Coubertin of universalism but against insisted amateurism unfortunately. In addition, the Olympic ideals offered a coherent set of values in which “non-elite participation was more important than the elitism of skill, and in which sportsmanship – meaning respect for opponents and for the rules that make sports meaningful - was more important than winning” (Whitson, 1997: 2). Indeed, though the professionalism of the Game has implied considerable benefits such as global media attention, commercial sponsorship, huge funding etc. it has also supplanted the spirit of amateurism which Pierre de Coubertin and Avery Brundage had sought hard to defend during their presidencies in the IOC and through their later lives. Again, the principles of “the Olympic Creed concerning the importance of taking part as opposed to winning are placed under a certain amount of strain when the direct and indirect financial rewards for winners are remarkable” (Toohey & Veal, 2000: 225).

In regard to the future development of the Olympic Games influenced by the manifestation of professionalism, both positive and negative aspects have been recognized

(International Olympic Academy, 2001). In terms of positive perspective, the best performers can act as role models and encourage new talent and promotion of the Olympic ideals and so on (International Olympic Academy, 2001). Nevertheless, negative influences brought by professionalism of sports in the Olympic Games have also emerged as one can see a growing number of athletes transferred from developing to developed countries have decreased the opportunity for equal participation. Besides, the rising number of individual contract conflicts with the contracts of national teams. Subsequently, to compete for different countries becomes easier and thus national pride decreases. And, professional athletes’ access to more competitions than amateurs results in imbalance in their motivation and performance (International Olympic Academy, 2001). Therefore, the above claims have reflected on a fact that it has become unproblematic for people to prefer professional performance rather than pure Olympic spirit as a tremendous process of mediaization, spectacularization, and commercialization on Olympic Games are abundantly clear (Henry, 2002).

Conclusions

In this paper, an attempt has been made to identify a number of issues relating to the development of the modern Olympic Games in the global context. It has thus sought to provide overview of the modern Olympic Games from explaining the spiritual and ritual difference between the Ancient Games and the modern Olympic Games, together with illustrating how the facts of commercialization and professionalism etc. have impacted the development of this mega sport event.

In respect of the response to the spiritual and ritual difference between the Ancient Games and the modern Olympic Games, this paper argues that the initial religious and ritual concerns of the ancient Olympic Games played a gradually reduced role. The modern Olympic Games have been transforming from a ‘symbolic and spiritual’ emphasis to a

‘concrete and practical’ demand by promoting peace and friendship among participating athletes and nations. Ironically, though some good conventional values of the Olympic Games are still been promoting and emphasizing by the IOC, the Games nowadays are apparently seen as more (or correctly to say almost completely) ‘commercialized’ and ‘professionalized’ in terms of manifestation. Such Games have given different ways despite that Pierre de Coubertin and Avery Brundage had sought to promote and maintain throughout their whole lives, in particular after the ‘successful’ 1984 Game in Los Angeles. Consequently, the Olympic Games system here may be characterized as an environment where ‘interests of commercialization and professionalism’ act mainly as a vehicle for the interests of individuals belong to the IOC, international corporations, some elite athletes etc. and not for those of groups as whole in the global village. The action taken overlaps between the interests of the IOC community (include IOC itself, the top ten sponsors, athletes and so on) and the forces beyond the IOC system in overt ways which have made this development of the Olympic Games somewhat different. More precisely, the system has been characterized by a tension between mechanisms of ‘modern’ development within recent decades, and ‘traditional’ forms of ancient Greeks and Pierre de Coubertin’s orientation.

References

Baker, W. J. (2000). If Christ Came to the Olympics. Sydney: New South Wales University Press.

Bale, J. & Christensen, M. K. (2004). Post-Olympism. In J. Bale & M. K. Christensen (Eds.),

Post-Olympism? Questioning sport in the Twenty-first Century (pp. 1-10). Oxford: Berg.

Barney,R. K. (1994). Golden Egg or Fool’s Gold? American Olympic Commercialism and the

Olympic Academy.

Cashman, R. (2004). The Future of a Multi-sport Mega-event: Is There a Place for the Olympic Games in a ‘Post-Olympic’ World? In J. Bale & M. K. Christensen (Eds.),

Post-Olympism? Questioning sport in the Twenty-first Century (pp. 119-134). Oxford:

Berg.

Chappelet, J. & Bayle, E. (2005). Strategic and Performance Management of Olympic Sport

Organizations. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Chatziefstathiou, D. (2004). For Sale and Wanted: The Olympic Games. Label 18, p 22-23. Donnelly, P. (1996). Prolympism: Sport Monoculture as Crisis and Opportunity, Quest, 48, p

25-42.

Foster, K. (2005). Alternative Models for the Regulation of Global Sport. In L. Allison (Ed.),

The Global Politics of Sport: The Role of Global Institutions in Sport (pp. 63-85).

London: Routledge.

Georgiadis, K. (2003). Olympic Revival: The Revival of the Olympic Games in Modern Times. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon.

Girginov, V. & Parry, J. (2005). The Olympic Games Explained: A Student Guide to the

Evolution of the Modern Olympic Games. London: Routledge.

Henry, I. P. (2002). Modernity, Postmodernity and Olympism. From Ritual to Record - from

Record to Spectacle: The Cultural Politics of Olympism. Paper to the 10th International Postgraduate Seminar on Olympic Studies.

International Olympic Academy (2001). Special Subject, Olympic Games: Athletes and

Spectators. International Olympic Academy 40th Session for Young Participants. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Nikolaou, L (2003). The Introduction of the International Olympic Academy. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Literature, and Art. Report of the Thirty- Fourth Session 18th July- 2nd August 1994. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Maguire, J. (1999). Global Sport: Identities, Societies, Civilizations. Cambridge: Polity. Melik-Chakhnazarov, H. E. (1998). The Olympic Truce- Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. Report

of the Thirty- Seventh Session 7th-22nd July 1997. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Moller, V. (2004). Doping and the Olympic Games from an Aesthetic Perspective. In J. Bale & M. K. Christensen (Eds.), Post-Olympism? Questioning sport in the Twenty-first

Century (pp. 201-210). Oxford: Berg.

Muller, N. (2004). Olympic Education. The Sport Journal 17 (1). Retrieved January 10, 2006 from http://www.thesportjournal.org/2004Journal/Vol7-No1/muller.asp

Payne, M. R. (1998).The Sponsoring and Marketing of the Atlanta Olympic Games. Report of the Thirty- Seventh Session 7th-22nd July 1997. Olympia: IOA.

Powell, J. T. (1999). Consolidated Report. Report of the Thirty- Eighth Session 15th-30th Jul8y 1997. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Schrettle, B. (2000). The Sacred Truce of Olympia Roots and Ideology. Report on the I.O.A.’s Special Sessions and Seminars 1998. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.

Tadesse, W. (1998). Amateurs and Professionals at the Ancient Olympics: Problems and

Prospects of Professionalism Today. Report on the I.O.A.’s Special Sessions and

Seminars 1997. Olympia: International Olympic Academy. Tames, R. (1996). The Ancient Olympics. Crystal Lake: Rigby.

Tomlinson, A. (2005). Olympic Survivals: The Olympic Games as a Global Phenomenon. In L. Allison (Ed.), The Global Politics of Sport: The Role of Global Institutions in Sport (pp. 46-62). London: Routledge.

Toohey, K. & Veal, A. J. (2000). The Olympic Games: A Social Science Perspective. Sydney: CABI Publishing.

Toomey, W. A. & King, B. J. (1984). The Olympic Challenge: Events, History, Athletes,

Records. Virginia: Reston.

Vigor, A., Mean, M. & Tims, C. (2004). After the Gold Rush: A Sustainable Olympics for

London. London: Demos.

Whitson, D. (1997).Olympic Sport, Global Media, and Cultural Diversity. Los Angeles: Amateur Athletic Foundation - Fourth International Symposium for Olympic Research. Yalouris N. (2001). The Olympic Games in Ancient Greece- Athletes and Spectators. Report

of the Fortieth Session 23rd July-8th August 2000. Olympia: International Olympic Academy.