Research Methodology

This chapter addresses the issues concerning execution of this study. It begins with the research framework under which both the interaction in an interpreting event and its process are investigated and analyzed. It proceeds with research design, including the scope of research, study population, research tools, data collection, and implementation procedures. It then ends with an account of data analysis procedures.

3. 1 Research Framework

Kalina (2002) suggested “quality cannot be determined in relation to the

interpreter’s output alone” (p. 124) and proposed a framework for identifying factors that affect quality. She maintained this framework might help to determine the potential quality of a given interpretation. In her paper, she examines two conference interpreting events as a service process instead of focusing on the interpretation as a text-product. Her scheme divides factors and conditions into those over which the interpreter has control and those s/he does not, but she could not decide whether and to what extent all these are measurable. In the end, she urged for cooperation with other disciplines in analyzing an entire conference for a holistic evaluation. In answering her call, this study adopts script methodology as one of the research tools, which Alford (1998) has proven potent to assess and improve on the process of professional services delivery.

Based on the literature review of this study, effective as script methodology is in determining customer satisfaction by identifying discrepancies in the scripts of both the provider and the client, it may not be able to assess the effect of the provider’s routine practices. For example, an interpreter may arrive early at the conference venue as is

see. However, as described in Chapter 2, because of the CIT’s strengths in reviewing current service procedures, when script methodology is applied jointly with it, the causes of satisfaction and dissatisfaction shall be unearthed. Therefore, this study consists of two research projects: one with the application of script methodology, and the other the CIT.

3. 2 Research Design

3. 2. 1 Scope of research

As indicated in the review of literature, types of interpretation—i.e., depending on where the interpreter works—range from conference interpreting to liaison interpreting (Hsieh, 2003). Roberts (2002) has identified two major subdivisions of interpreting, court interpreting and community interpreting, under the blanket term of liaison interpreting.

She has argued that these three types of interpreting are at very different stages of professionalization. Therefore, with consideration of this factor, time, and resource constraints, this study is limited to discussions of conference interpreting.

3. 2. 2 Study population

Pöchhacker (2001) has noticed a peculiar phenomenon in the research community of interpretation studies that despite his/her importance the employer of professional interpreters, the conference organizer, has captured very little attention from scholars seemingly keen to investigate interpreting quality. Therefore, this study is intended to address the issues of quality and satisfaction in the stance of the interpretation client.

This goal is to be attained through a comparison of the perspectives of the interpreter and the conference organizer. These two roles in an interpreting event are therefore the two populations of this study.

3. 2. 3 Research Tools 3. 2. 3. 1 Script methodology

According to the literature review, scripts reveal expectations of the service provider and the client for a service encounter in a chronological order, and therefore through subsequent comparison of both parties scripts a researcher may determine whether and to what extent a client’s expectations are met, and further identify suspected causes of customer dissatisfaction (Hubbert et al., 1995). Bower et al. (as cited in Ling, 2000) developed retrospective self-report measures for researchers to tap into

respondents’ memory for their scripts. Ling (2000) broke their measures down to three steps as follow:

1) Step 1—self report: The respondent is directed to draw on the sum of their previous experiences of a given service and note down each step taken by both her/himself and his/her counterpart in chronological sequence.

2) Step 2—core script elicitation: All the respondents’ scripts are entered into their own group’s master list of actions (the service provider vs. the customer). Each action is then tallied for its frequency on the list as a proportion to the number of this group’s respondents. Actions with a frequency over 40% are then elicited to form a core script (John & Whitney, 1982).

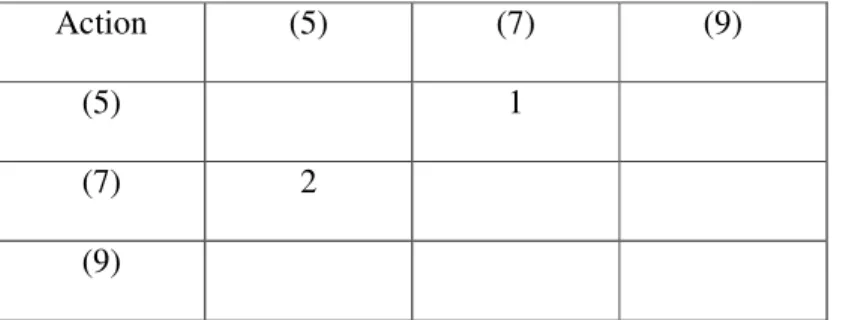

3) Step 3—paired comparison: The order of the actions in the core script is then determined through a paired-comparison technique, as shown in Figure 3.1, developed by John and Whitney (1982). For example, a core script consists of three actions, originally numbered (5), (7) and (9). The researcher has to draw up a grid with each action as both a row and a column header. In the cell is the number of times an action in the row precedes the one in the column.

Subsequent adjustments are made to the order of the actions according to a

comparison of each cell’s number with that of its corresponding cell one by one.

See the figure below as an example. The number 2 in the crossing of row (7) and column (5) indicates that action (7) precedes action (5) in two respondents’

scripts; likewise, the number 1 in the crossing of row (5) and column (7) indicates that action (5) precedes action (7) only in one respondent’s script.

Therefore, action (7) takes place earlier than action (5) more often and they should be reversed in order. The sequence of these three actions in the core script is then changed to (7), (5), and (9).

Action (5) (7) (9)

(5) 1

(7) 2

(9)

Figure 3. 1 Paired comparison of sequential order of actions

Source: Ling, Y. L. (2000).

3. 2. 3. 2 CIT (Critical Incident Technique)

Bitner, Booms, and Tetrault (1990) applied CIT to study the consequential events or behaviors of contact employees in three service industries. They collected answers to the following questions (p. 74):

Think of a time when, as a customer, you had a particularly satisfying

(dissatisfying) interaction with an employee of an airline, hotel, or restaurant.

When did the incident happen?

What specific circumstances led up to this situation?

Exactly what did the employee say or do?

What resulted that made you feel the interaction was satisfying (dissatisfying)?

Bitner, Booms, and Mohr (1994) duplicated the first study on contact employees.

They were asked to first describe a recent incident in which a customer had a particularly satisfying (dissatisfying) interaction with them or their fellow employee, and then to answer the following questions (p. 97):

When did the incident happen?

What specific circumstances led up to this situation?

Exactly what did you or your fellow employee say or do?

What resulted that made you feel the interaction was satisfying (dissatisfying) from the customer’s point of view?

What should you or your fellow employee have said or done? (for dissatisfying incident only)

Bitner et al. (1990, 1994) specified their request for the accounts of incidents that conform to the four following criteria (p. 73, 1990):

Involving employee-customer interaction

Being very satisfying or dissatisfying from the customer’s point of view Being a discrete episode

Having sufficient detail to be visualized by the interviewer.

The questionnaires of this study were designed partly based on the above two sets of questions.

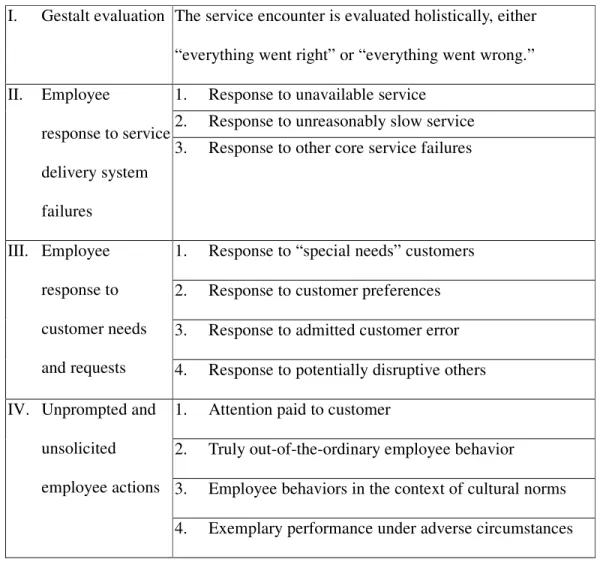

Bitner et al. (1990; 1994) have developed a classification scheme to sort out the collection of incidents, which includes twelve categories under three groups of generic events and behaviors (Bitner et al., 1990). Ling (2000) conducted a similar study on the dental and hairstyling services in Taiwan, and gestalt evaluation became independent from the third group. The groups and categories after Ling’s modification are shown as

shown in Figure 3.2. Together as a system, it is abbreviated in this study as the BBTM classification scheme, and is elaborated upon in the section of data analysis procedures.

I. Gestalt evaluation The service encounter is evaluated holistically, either

“everything went right” or “everything went wrong.”

1. Response to unavailable service 2. Response to unreasonably slow service II. Employee

response to service delivery system failures

3. Response to other core service failures

1. Response to “special needs” customers 2. Response to customer preferences 3. Response to admitted customer error III. Employee

response to customer needs

and requests 4. Response to potentially disruptive others 1. Attention paid to customer

2. Truly out-of-the-ordinary employee behavior

3. Employee behaviors in the context of cultural norms IV. Unprompted and

unsolicited

employee actions

4. Exemplary performance under adverse circumstances

Figure 3. 2 The BBTM Classification Scheme first developed by Bitner et al. (1990;

1994), and later modified by Ling (2000)

3. 2. 4 Data collection

3. 2. 4. 1 Design of questionnaires

The first draft of two questionnaires is based on the application procedures of these two research instruments to collect data from the two populations of this study. One is

intended to solicit responses from the interpreter, and the other from the conference organizer. Both consist of four parts. In the first part of both questionnaires, the

respondent is directed to first read through a script for opening a bank account, and then follow it as an example to write down each step taken towards the completion of

interpreting services in chronological order. For the second and third parts, after reading the exemplary incidents, the respondent is asked to first provide an account of interpreting services experience that is satisfactory, and then another account that is dissatisfactory both in the stance of the client from his/her own perspective, either as an interpreter or a conference organizer. Finally, the respondent is inquired about background information with regard to interpretation services experience.

The first draft of the questionnaires was presented to a marketing scholar and the advisor of this study, a conference interpretation instructor, for revision. The marketing scholar suggested the request for accounts of satisfactory and dissatisfactory events should precede the elicitation of the script. The interpretation instructor made corrections in the wording of the questionnaire’s request for responses.

The second draft was later completed with the integration of the above opinions into the design of the questionnaires. The questionnaire for the interpreter was then administered to a novice interpreter. It took more than forty-five minutes to finish.

Afterwards, concern with the time-consuming and laborious nature of the questionnaire was raised. In addition, after a close inspection of the answers, it was found that they were not as complete as expected, and request for clarification in meaning was necessary.

A pretest was conducted on a conference organizer with the questionnaire of the second edition for the client. Ambiguity in the meaning of the responses and reluctance to complete the entire questionnaire was detected. After discussion on the above problems with the marketing scholar, this study decided to organize an interview with potential

respondents based on the questionnaires instead of having them fill in the questionnaire manually.

3. 2. 4. 2 Implementation procedures

The research procedures include selecting samples, conducting interviews, and confirming transcription of responses.

3. 2. 4. 2. 1 Sample selection

This study is intended to investigate how quality in conference interpretation services is perceived, and also what determines client satisfaction in general. Therefore, a diversified body of respondents was preferred.

3. 2. 4. 2. 1. 1 Client—conference organizers

Clients’ contact information was requested from a local interpreting equipment rental company. Fourteen clients were selected from the company’s customer profiles, and a final list of twenty organizations was put together with the information of the other six obtained from different sources. Three of them are government agencies, four

non-profit organizations, two political organizations, seven private corporations, one media outlet, and three state-owned corporations. The topics of conferences held by these organizations include environmental protection, trade and development, competition practices, financial security, investment, international relations, labor and management, public relations, law, marketing, culture and education, politics, and regional security.

3. 2. 4. 2. 1. 2 Client—conference organizers Service provider—interpreters

Difference in career seniority is the primary consideration in selecting respondents from the pool of conference interpreters so as to discern whether working experience may

contribute to customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction and whether the elaborateness of a respondents’ script could be tied to his/her service seniority. Eleven interpreters of different ages and lengths of service were enlisted. The above decision is based on Robert’s statement (2002) that reality in the marketplace does not allow interpreters to confine their professional activities to a certain setting. Given the assertion that interpreters are supposed to be adaptive to various working contexts, it would seem reasonable to presume interpreters’ versatility when it comes to subject matters they deal with. Therefore, this study does not take into account interpreters’ specialties even though they may have had years of experience under their belts interpreting for conferences of a particular trade or discipline so they may be crowned as an expert interpreter in a certain field. Namely, the experiences chosen interpreters draw upon are bound to be across industries.

3. 2. 4. 2. 2 Interviews

Only the two respondents who helped to complete the pretests provided their responses by filling in the questionnaires. Interviews were then carried out one by one with the conference organizers and interpreters from the first week of November to the second week of December in 2004. Individual interviews lasted from fifteen to forty minutes. Responses to the questions on the questionnaire were elicited without

interruption unless ambiguity in meaning was detected and clarification was necessary.

The gist of each interview was noted down on a blank copy of questionnaire on the spot and all the interviews were also recorded for later reference and transcription.

3. 2. 4. 2. 3 Transcript confirmation

Transcripts were later emailed to the respondents for confirmation. Corrections

were then made.

3. 3 Data Analysis

The collection of data includes satisfactory incidents and dissatisfactory incidents from both the conference organizers and the interpreters, and their scripts. Two sets of procedures are applied to the analyses for the data: one is CIT and the other is script methodology.

3. 3. 1 Script methodology

The interpreters’ general script and that of the conference organizers undergo a matching process. The general script is the modified core script after adjustments in sequential order are made through paired comparisons of individual actions. The results of comparison will subsequently be checked against the findings of other empirical studies of script methodology and the prescribed procedures dictated by the three interpreters’ professional associations.

3. 3. 2 CIT

After all the stories are sifted through for valid accounts, the next step in the study is to identify generic events and behaviors that cut across the conference interpreting services industry and cause the client to render a service encounter as satisfying or dissatisfying.

The collected data are first read through carefully time and again, and then

categorized in a systematic and rigorous manner. All the valid incidents, both satisfactory and dissatisfactory, reported in the CIT research project are placed in different categories of the Service Theater and BBTM classification schemes. Detailed classification

procedures follow closely the review of the studies by Bitner, Booms, Tetreault, and Mohr

(1990, 1994), Grove and Fisk (as collected in Lovelock, 2001) and Ling (2000, 2003).

The operational definitions of the variables in two classification schemes, i.e. the service theater and the BBTM modified by Ling (2000), have been adapted and are prescribed as follow.

3. 3. 2. 1 The Service Theater Classification Scheme

This scheme consists of four groups and fourteen categories under them.

A. Setting: the physical environment or facilities in or through which the service provider interacts with the client and delivers the service

a. Décor: decorations at the conference venue; the created atmosphere

b. Layout: the position of the interpreters’ booth; the location of the podium from behind which the interpreter speaks relative to the speaker (Kalina, 2002) c. Interpreting facilities: the soundproof quality of the interpreter’s booth; the volume of the interpreter’s voice in the listener’s earphone or that escapes from it; the degree of acoustic intervention in the reception of interpretation B. Actors: the service provider, including the interpreters, their agent, the staff of the

interpreting equipment rental company

a. The appearance and personal attributes of the service provider: voice quality, accent, articulation, poise, public speaking; dressing, makeup (Kalina, 2002) b. The attitudes and behavior of the service provider: the manner in which the

service is delivered or the service provider interacts with other immediate stakeholders in a conference setting

c. The level of excellence of the service provider’s technical skills: regardless of their performance or task difficulty in a particular event, the personnel’s average ability to deliver interpretation to the audience without complaints in return

d. The commitment of the service provider to the promise made to the client:

preparation in advance; keeping confidentiality; honoring the agreement C. Audience: the client, or the persons receive services

a. The willingness and attitude of the client to cooperate in the service production:

whether or not the client is willing to facilitate the completion of the service, and in what manner s/he does it

b. The competence of the client in facilitating the service production: whether a client has the knowledge and ability to assist the service provider in delivering the service and how well s/he does it

c. Interactions among clients: two-fold in this regard—customer compatibility (Matin & Pranter, 1989), meaning whether the client appreciates the service provider’s other clients; policing the service beneficiary, meaning the client’s prevention of and dealing with disruptive behaviors in the audience

D. Performance: the client’s service experiences; the service provider’s professional work; the result of the service or its effect on the client

a. Quality of the core service: quality in interpretation relative to its price b. Service delivery: the speed at which the service is delivered; the time the

client is kept on waiting

c. Service process and system design: the process of service delivery being smooth or jolty; the design of an interpreting event as a package

d. Integrated performance: having multiple features stated in the above

3. 3. 2. 2 The BBTM classification scheme modified by Ling (2000)

This scheme consists of four groups and twelve categories under them.

I. Gestalt evaluation

1. Holistic evaluation: the client is unable to attribute dis/satisfaction to any single feature of the service encounter. The service encounter is evaluated holistically, either “everything went right” or “everything went wrong”;

success or failure in the core service delivery coupled with other factors.

II. Employee response to service delivery system failures: incidents in this group are related directly to failures in the core service (interpretation) and inevitable system failures that occur for even the best of service providers.

1. Response to unavailable service: in the event of normally available services lacking or absent, whether apology, compensation, explanation or even suggestion of alternatives is offered to the client

2. Response to unreasonably slow service: in the event of services or the provider’s performances perceived as inordinately slow, whether apology, compensation, explanation or even suggestion of alternatives is offered to the client

3. Response to other core service failures: in the event of other aspects of the core service not meeting basic performance standards for the industry, whether apology, compensation, explanation or even suggestion of alternatives is offered to the client

III. Employee response to customer needs and requests: incidents in this group contain either an explicit or inferred request for customized service (adaptation of the service delivery system to suit the individual client’s unique needs) from the client’s point of view.

1. Response to “special needs” customers: incidents involving customers who have special medical, dietary, psychological, language, or sociological difficulties.

2. Response to customer preferences: incidents when, from the client’s perspective, “special requests” (reflecting personal preferences unrelated to his/her sociological, physical, or demographic characteristics) are made, such as adopting preferred terminology, and performing tasks not included in the pre-conference agreement

3. Response to admitted customer error: incidents in which a client’s error strains the service encounter, such as working the service provider overtime,

changing the conference agenda or content of presentations, providing insufficient or inadequate conference materials

4. Response to potentially disruptive others: incidents in which the service provider copes with disruptive person(s) properly or not

IV. Unprompted and unsolicited employee actions: this group includes events and the service provider’s behavior that are truly unexpected from the customer’s point of view.

1. Attention paid to customer: incidents in which the level of attention paid the customer is viewed very favorable or very unfavorably

2. Truly out-of-the-ordinary employee behavior: incidents in which the service provider does some small thing that for the customer translates into a highly satisfactory or dissatisfactory encounter, such as extraordinary actions or expressions of courtesy or thoughtfulness or on the contrary yelling, rudeness, etc.

3. Employee behaviors in the context of cultural norms: incidents reflecting provider behavior relating to cultural norms such as punctuality, dutifulness, honesty, or on the contrary discrimination, theft, etc.

4. Exemplary performance under adverse circumstances: incidents in which the

client is particularly impressed/displeased with the way a provider handles a stressful situation

After being sorted out according to the above two sets of definitions, these incidents were then each tagged with two labels. One indicated the end result of sorting with the Service Theater classification scheme, and the other with the BBTM. These results were subsequently to be analyzed, and their implications in the general context of conference interpreting discussed based on the review of literature in Chapter 2.

3. 3. 3 Limitations of the script methodology

Script methodology has been applied primarily to study a service relationship between two parties. However, as indicated in the review of the literature, an intermediary also plays a vital role in an interpreting event. Therefore, it is considered a minor study population. Due to constraints in time and resources, this study only interviewed the interpreting equipment rental company that provided the list of clients for its script. The analysis of its script is included in the comparison and contrast between the clients’

general script and that of the interpreters’.