癌症病友線上故事 — 台灣某電子佈告欄癌症病友自介貼文之言談分析

全文

(2)

(3) 摘要 網路是現代人尋求資訊以及建立社會網路的重要管道。透過網路尋求醫療相關資 訊也因為網路使用的廣泛而蔚為盛行(Diaz et al. 2002) ,很多不常在社交場合被公開 討論的醫療健康議題,例如:癌症,也因為網路可以匿名的特性而在網路上得到很好 的討論機會。在現代社會中,癌症被認為是一項重症也因此讓其患者感到無可奈何, 癌症診斷本身以及其後續治療並且成為病患感到焦慮的緣由(Merckaert et al. 2010)。 在此種情況之下,癌症病患不僅需要專業的醫療處置也需要來自他人的社會支持。然 而,他們可能會因為擔心受到汙名化以及不一樣的對待(Hilton at al. 2009)而避免在 面對面的場合當中承認自己的罹癌身分,因此,透過網路就成為他們可以完全表達自 我的好方法。除此之外,由於癌症病患的每一社會心理特質都有可能成為其生活品質 的預測指標,了解他們的社會心理特質就成為一件很重要的事(Parker et al. 2003)。 因此,本研究試圖透過分析癌症病患在網路討論區所張貼的自我罹癌經驗以了解他們 的社會心理特質。本研究首先檢視言談特色,接著針對這些言談特色所反映出的癌症 病患社會心理特質進行進一步的討論。 本研究所檢視的線上社會媒體是現今在台灣最被廣泛使用也最受歡迎的 KDD (化名)電子佈告欄,而分析語料「自介貼文」則是來自 KDD 當中的一個癌症相關看 板(以下簡稱為「癌症看板」或「KDD 癌症看板」),此看板的參與者大都為癌症病 友(以下稱為「罹癌板友」)或親友(以下稱為「癌症病患親友」)。自介貼文通常是 此看板板友的第一次貼文或第一次公開介紹自己,而其內容包含了癌症病患的個人基 本資料、從獲知診斷那一刻起至治療過程的種種罹癌經驗與情緒的抒發等。本研究共 得 58 篇來自癌症病患本人的自介貼文,它們的貼文日期為 2005 年 10 月 29 日至 2012 年 6 月 29 日。本研究採用「言談分析」(discourse analysis)的角度檢視自介貼文內 容。 經過檢視,本研究發現以下三個言談特色: (1)高達 84%的癌症病患自介貼文有. i.

(4) 主動「揭露年齡」(age-disclosure)的言談模式。年齡揭露的句型共有六種形式:現 況式、前瞻式、回顧式、條列式、直接式以及間接式。本研究將條列式以及直接式稱 為「中性揭露句型」,將另外四種句型(現況式、前瞻式、回顧式以及間接式)稱為 「非中性揭露句型」;(2)罹癌板友傾向提及罹癌前生活的「正常」與「美好」 ,美 好包含了健康的生活習慣、良好的健康狀況、有前途的工作、順遂的生活以及良好的 教育程度,除此之外,他們也描寫到他們意想不到癌症診斷的一面,此種描述包含兩 個概念:沒有癌症家族病史以及沒想過自己會成為癌症看板的一員;(3)超過一半 (55%)的罹癌板友以鼓勵的話語為他們的自介貼文收尾,他們所提供之鼓勵的話語 可分為三類,第一類包含帶有祈禱和祝福的字詞,例如:‘希望’、‘願’和‘祝’,第二類 則是包含‘加油’此一詞彙,而第三類包含了可以激勵人心與給予正面力量的鼓勵詞 句。 年齡揭露此一言談特色顯示出無論是罹癌板友或是癌症病患親友都是屬於 20-29 歲的年輕族群。根據「年輕」以及以上所提及的三個言談特色,本研究推導出以下三 個和罹癌板友社會心理特質相關的論點: (1)縱使此族群之罹癌板友並非醫療專業人 士,他們本能地意識到年齡於「醫療健康」此情境脈絡的言談討論是重要的基本資訊; (2)他們對於罹癌前正常與美好生活的描述反映出他們難以接受癌症診斷的一面, 而以下三個觀點更說明了他們對於癌症診斷的排斥與抗拒:第一,青壯年階段(20-29 歲)罹癌有悖於一般人對身體健康發展階段的「規範性期望」 (normative expectation) 。 第二,罹癌板友在對於罹癌事實提出質疑的時候附帶提到自己的年齡,代表著「年記 輕輕竟得惡疾」是引發他們無法面對事實以及感到憤怒的緣由(例如:‘為甚麼會是 我?我才 27 歲!!’)。第三、在揭露年齡的時候使用蘊含「違背期待」的副詞‘才’ (例如:‘我才 27 歲!!’)也透露了他們拒絕年輕罹癌的態度; (3)參與 KDD 癌症 看板以及提供鼓勵的話語則反映出他們對於相互支持的需求。 由於年輕癌症病患為癌症看板的主要族群,此看板提供了年輕病患一個專屬於他 們所屬年齡層的心理與社會支持空間。醫療人員對於相關線上病友交流園地的參與有. ii.

(5) 助於了解此年齡層癌症病患的社會心理需求,甚至有助於推動衛教資訊之宣導。此 外,本研究從以下三個方向增加了年齡在醫療脈絡下的理解:年齡是(1)病患疾病 歷程的參考點、(2)人類生命歷程的參考點以及(3)病患抗拒違背身體健康發展階 段規範性期望之診斷的原因。. 關鍵字:線上罹癌故事;年輕癌症病患;電子佈告欄;線上社會支持;言談分析;網 路醫療溝通;電腦輔助溝通;年齡揭露;社會媒體;社會心理特質. iii.

(6) ABSTRACT The Internet is an important contemporary channel that allows people to find information and create social networks. With the universality of Internet use, searching for medical information online is a trend (Diaz et al. 2002). Many health-related topics, such as cancer, which are not typically discussed openly in social conversation, are discussed online because of the anonymity granted to participants. In modern society, cancer is perceived as a serious disease and often leads patients to feel helpless. Being diagnosed with cancer and its subsequent treatment are stressful events (Merckaert et al. 2010). While cancer patients need is medical treatment, they also require support from others. However, concern about others’ reactions and the fear of being treated differently or stigmatized (Hilton at al. 2009), may lead cancer patients to feel embarrassed about acknowledging their identity as cancer patients in face-to-face communication. Communicating online is a practical vehicle for patients to express themselves wholly. Understanding a cancer patient’s psychosocial character is important because their psychological state can act as predictors of their quality of life (Parker et al. 2003). Thus, the present study aims to have a better understanding of cancer patients' psychosocial characteristics by examining their accounts of illness experiences posted on Internet forums. The linguistic features were first examined and then the psychosocial characteristics reflected within the linguistic features are further discussed. The online social medium under investigation in the present study is a Taiwanese Bulletin Board System named KDD (a pseudonym) which is the most famous and widely used one in Taiwan at present. The data examined in the present study, self-introduction posting, is collected from its cancer-related board (‘cancer board’ or ‘KDD cancer board’ hereafter) whose members are mostly cancer patients (‘patient members’ hereafter) and. iv.

(7) relatives and friends of cancer patients (‘non-patient members’ hereafter). The self-introduction postings which are usually the first posting from members in the cancer board or their first time to introduce themselves officially contain cancer patients’ personal basic information, experiences from the time they received their cancer diagnosis to treatment processes and expression of emotions. In total, 58 self-introduction postings by cancer patients were collected. These were posted between October 29, 2005 and June 29, 2012. Empirical discourse analysis was employed to analyze the self-introduction postings. After investigation, three linguistic features are found: (1) 84% of patient members spontaneously disclosed their age in the content of their self-introduction postings, either age at the time of posting or age at the time of their cancer diagnosis. The linguistic pattern of age-disclosure can be divided into six types: stative, prospective, retrospective, listing, direct and indirect. Listing and direct formats are termed as ‘neutral pattern for age-disclosure’ in the present study which made up 53% of all types of age-disclosure formats. The other 47% are termed as ‘non-neutral pattern for age-disclosure’ which consisted of stative, prospective, retrospective and indirect format. (2) Patient members tended to provide descriptions of a sense of normalcy and satisfaction with their lives prior to the cancer diagnosis. The satisfaction they mentioned was derived from a number of factors. These included a healthy lifestyle, good physical condition, promising job, good life and educational background. Apart from these, they also provided descriptions about their counter-expectation to the cancer diagnosis which involved two concepts: having no family history of cancer and the unexpected membership in the KDD cancer board. (3) More than half (55%) of the patient members ended their self-introduction postings with words for encouragement which can be classified into three types. The first type contained words with the meaning of praying and blessing, like ‘希望/hope,’ ‘願/wish’ and ‘祝/bless’ and the second type included the phrase ‘加油/go for it’. The third type contained. v.

(8) encouraging words. The feature of age-disclosure showed that being young (in the age group of 20 to 29) is the social characteristic of all members of the cancer board, including patient members and non-patient members. Based on their being young and the above three linguistic features, we forward three arguments with regard to patient members’ psychosocial characteristics: (1) Even though they are not medical professionals they intuitively know the importance of age in medical contexts. (2) They had difficulties in accepting their cancer diagnosis as reflected by their description of a normal and good life prior to the cancer diagnosis. Moreover, they even resist to the cancer diagnosis as supported by the following three viewpoints. First, getting cancer at such a young age runs contrary to the normative expectation of physical health development. Second, presenting their own age when expressing anger about getting cancer strongly suggests that their age is a contributing factor to their anger (e.g. ‘Why me? I am only 27’). Third, the use of evaluative adverb, such as ‘only,’ when disclosing their own age (e.g. ‘I am only 27’) further emphasizes their vehement rejection of their cancer diagnosis. (3) They were in need of mutual support as reflected by their participation in KDD cancer board and their provision of words for encouragement. Since young cancer patients are the most frequent users of the cancer board, it provides them with an exclusive space to fulfill their psychosocial needs. A dedicated forum also functions as an invaluable corpus of patient voices that can inform health professionals of the needs and concerns of young cancer patients. Moreover, it can equally provide an efficient vehicle for the dissemination of cancer treatment education by health professionals. The present study enhances the understanding of age in medical contexts in the following three directions: Age is (1) a point of reference of a patient’s disease trajectory, (2) a point of reference of a person’s life course, and (3) the reason for denial. vi.

(9) when a patient is faced with a disease that is foreign to his/her expectation because it violates the assumed normal physical development.. Keywords: cancer stories online; young cancer patients; bulletin board system (BBS); social support online; discourse analysis; online health communication; computer-mediated communication; age-disclosure; social media; psychosocial characteristics. vii.

(10) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of my thesis might not go so smoothly without the assistance and supports from those who are around me. First of all, my deepest gratitude goes to my advisor, Dr. Mei-hui Tsai. Her research interests are so distinctive and attractive to me that I decided to work and do research with her. The experiences of taking her courses even guided me to choose the present research topic. During the writing of this thesis, she inspired me a lot by providing me with valuable ideas, advices and comments. Her instruction enriched the contents of this thesis. Next, I am also very grateful to the committee members of my oral defense, Dr. Shin-mei Kao and Dr. Tsung-Hsueh Lu. Thanks them for spending time to read my thesis and providing me with practical suggestions that helped to enhance the quality of my thesis. The supports from my schoolmates are also important for me. Sophia Chang, a senior of mine, helped to release my worries by patiently answering all kinds of questions from me. Kelly Chuang and Sherry Lin, my fellow classmates, enabled me to have energy to complete my thesis by providing me with mutual encouragement. Celia Liao, Nikole Song and Sherry Chou, my junior classmates, helped me with the preparation and the release of my nervousness by accompanying me during my oral defense. Members in the Office 26630 always brought me joy which took me temporarily away from the pressure of writing thesis. Andrew Stoddart, my English consultant, helped to improve the writing of my thesis. Because of their supports, I am able to conquer the challenges. Last but not least, I would like to express my profound gratitude to my beloved family members. Thanks them for in favor of my choices and having great confidence in me. Their tender solicitude enabled me to concentrate wholly on my thesis and it was their loving care that backed me up during my journey of writing the thesis.. viii.

(11) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT (CHINESE) ...................................................................................................... i ABSTRACT (ENGLISH) .................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... viii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... ix LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... xi LIST OF EXCERPTS ......................................................................................................... xii LIST OF EXAMPLES ........................................................................................................ xii GLOSSARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................... xii. CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................1 1.1 Background and Motivation ......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the Present Study ........................................................................................ 3 1.3 Research Questions....................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Preview of the Following Chapters .............................................................................. 4 CHAPTER TWO. LITERATURE REVIEW ......................................................................6. 2.1 Computer-Mediated Communication ........................................................................... 6 2.2 Online Health Communication ..................................................................................... 7 2.3 Storytelling and Narrative Medicine ............................................................................ 9 2.4 Social Support for Cancer Patients ............................................................................. 11 2.5 Age-Disclosure ........................................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY ...........................................................................16 3.1 Data Collection ........................................................................................................... 16 3.2 Data Analysis .............................................................................................................. 19 CHAPTER FOUR. FINDINGS .........................................................................................31. 4.1 Age-Disclosure ........................................................................................................... 31. ix.

(12) 4.2 Normal and Good Life Prior to Cancer Diagnosis ..................................................... 41 4.3 Words for Encouragement ..........................................................................................45 CHAPTER FIVE. DISCUSSION ......................................................................................49. 5.1 The Meaning of Age ................................................................................................... 50 5.2 Resistance to the Shocking Cancer Diagnosis ............................................................ 53 5.2.1 Cancer Diagnosis is Unexpected and Unforgettable ........................................... 53 5.2.2 Resistance to Cancer Diagnosis ........................................................................... 57 5.3 Social Support............................................................................................................. 65 CHAPTER SIX CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATION ..................................................71 6.1 Summary of Main Findings ........................................................................................ 71 6.2 Implications of the Present Study ............................................................................... 73 6.3 Limitations of the Present Study ................................................................................ 74 6.4 Suggestions for Further Studies .................................................................................. 74 6.5 Contributions .............................................................................................................. 76 REFERENCES .....................................................................................................................78. x.

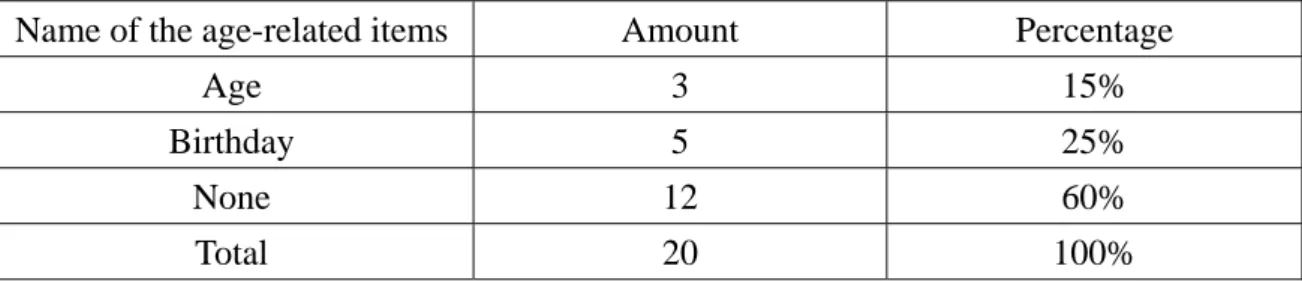

(13) LIST OF TABLES Table 3.1 Demographic information for the 58 self-introduction postings by patient members .........17 Table 4.1 The number of times each type of age-disclosure format was used.....................................32 Table 4.2 Percentage of the age-related items in self-introduction postings form in the 20 randomly selected boards .....................................................................................................................35 Table 4.3 Rate of age-disclosure in self-introduction postings in the 20 randomly selected boards ...38 Table 4.4 The type of age patient members who spontaneously disclosed their own age mentioned .38 Table 4.5 Patient members’ age at posting and age at cancer diagnosis ..............................................39 Table 4.6 Examples of descriptions of a sense of satisfaction with life prior to cancer diagnosis from the self-introduction postings by patient members ..............................................................42 Table 4.7 Examples of descriptions of the counter-expectation of getting cancer diagnosis from the self-introduction postings by patient members ....................................................................44 Table 4.8 Examples of words for encouragement from the self-introduction postings by patient members ...............................................................................................................................45 Table 5.1 Total number of people and total number of cancer patients in 2010 in Taiwan .................58 Table 5.2 Examples of the use of ‘才/only’ plus own age from the self-introduction postings by non-patient members ............................................................................................................64. xi.

(14) LIST OF EXCERPTS Excerpt 4.1 Words for encouragement with encouraging words-1 .......................................................46 Excerpt 4.2 Words for encouragement with encouraging words-2 .......................................................47. LIST OF EXAMPLES Example 3.1 Self-introduction posting by one of the patient members in KDD cancer board .................21 Example 3.2 Self-introduction posting by the patient member who took the lead in writing in listing format ...................................................................................................................................27 GLOSSARY OF TERMS TERM. DEFINITION. age-disclosure (Coupland et al. 1989). spontaneous reference to one’s own age. age at posting. age at the time of posting self-introduction. age at cancer diagnosis. age at the time of receiving cancer diagnosis. non-patient members. members of KDD cancer board who are relatives and friends of cancer patients. patient members. members of KDD cancer board who are cancer patients. . xii.

(15) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background and Motivation The Internet is an important contemporary channel that allows people to find information and create social networks. Therefore, more and more people rely on the immediacy and convenience of the Internet to fulfill their informational and communication needs (Cotten & Cupta 2004). In Internet communication (i.e. computer-mediated communication), there is no need to reveal one’s real identity in life. Thus, one’s personal and private information, such as, age, educational level and appearance can be exempt from being exposed. This is also the reason why the Internet can be a major medium for social activities. With the universality of Internet use, searching for medical information online is a trend (Diaz et al. 2002). Many health-related topics, such as cancer, which are not typically discussed openly in social conversation, are discussed online because of the anonymity granted to participants. In Taiwan, there is a Bulletin Board System (BBS) named KDD (a pseudonym). Within KDD, there is a cancer-related board for cancer patients, as well as relatives and friends of cancer patients, to have interaction under conditions of anonymity. As cancer is generally perceived as a serious or incurable disease, patients are almost invariably reticent to publicly discuss their health condition. Consequently, the Internet provides wonderful opportunities for cancer patients and their relatives or friends to get support from online support groups (Klemm et al. 1998). In modern society, cancer is a serious disease for which the morbidity and mortality are well acknowledged by the general public and which causes its patients to feel helpless.. 1.

(16) Moreover, cancer patients experience a variety of psychological distresses beginning with getting the cancer diagnosis to their subsequent treatment. Stark and House (2000) discuss in their study the problems of anxiety in cancer patients and note that the disease itself and its treatment are two factors that cause anxiety in cancer patients. Receiving a cancer diagnosis and the undergoing of its treatment are stressful events (Merckaert et al. 2010) because they may result in disabilities or functional restrictions, which further lead to variety of psychosocial problems (van’t Spijker et al. 1997). In this situation, what they need is not only medical treatment, but also understanding and support from others, no matter from medical professionals, fellow patients or friends and relatives. Charon (2001a) also stated that apart from the scientific ability in terms of medical treatment, doctors also need the ability to listen to patients’ stories in order to help patients coping with the disease. However, because of the concern about others’ reaction and the fear of being treated differently or stigmatized (Hilton at al. 2009), patients with cancer may feel embarrassed to identify themselves as cancer patients in face-to-face communication. Even if they do not feel uncomfortable when talking about themselves in public, they may keep very personal or private matters in mind (Caughlin et al. 2011) or they may want to protect themselves, participants in the conversation or their relationship between their selves and others (Donovan-Kicken & Caughlin 2010). Therefore, going online is a practical vehicle for patients to express themselves wholly. Understanding a cancer patient’s psychosocial character is important because their psychological state can act as predictors of their quality of life (Parker et al. 2003). Thus, the present study aims to have a better understanding of cancer patients' psychosocial characteristics by examining their accounts of illness experiences posted on Internet forums.. 2.

(17) 1.2 Purpose of the Present Study As stated above, the present study aims to understand cancer patients’ psychosocial characteristics by looking into their own accounts. Because of the widespread use of the Internet and the potential benefits of engaging in online discussion, this study is focused on cancer patients’ accounts shared online. The online medium under investigation in the present study is the cancer-related board in the KDD Bulletin Board System (‘cancer board’ or ‘KDD cancer board’ hereafter). We choose to focus on cancer patients’ psychosocial characteristics by linguistically analyzing their self-introduction postings on the KDD cancer board. In the present study, the self-introduction posting is the posting through which participants using the KDD cancer board (most of whom are cancer patients and relatives and friends of cancer patients) introduce themselves officially for the first time. Its contents include cancer patients’ personal basic information, their experiences from the time they got the cancer diagnosis to treatment processes and expression of emotions. These contents not only help us understand the mental processes cancer patients go through but also provide medical professionals with insights into health care for cancer patients. Therefore, self-introduction postings from cancer patients are the focus of the present study. In our preliminary analysis of the collected data, we found that most of the cancer patients (84%) mentioned their age-related information in self-introduction postings, for example their chronological age or the age when they got diagnosed with cancer. Topics about age are sensitive or even tabooed in social interaction, especially for middle-aged adults and those who reach a certain marriageable age. Thus, only the ages of elderly people and children are acceptable topics of conversation (Coupland et al. 1989); Moreover, we normally do not talk about our own age, even making it difficult for others to guess or know our age, nor do we ask others their age. However, as high as 84% of cancer patients. 3.

(18) using the KDD cancer board spontaneously mention their age-related information even though they can choose not to reveal their private information. We adopt the term ‘age-disclosure’ from Coupland et al. (1989) to refer to the phenomenon of cancer patients’ spontaneous reference to their own age. So what motivates age-disclosure? Besides this feature, are there any other linguistic features of the self-introduction postings by cancer patients? And, can cancer patients’ psychosocial characteristics be reflected or shown by these linguistic features? The present study aims to investigate the above-mentioned phenomena.. 1.3 Research Questions Accordingly, our research questions are presented as following: (1) What are the linguistic patterns of age-disclosure in the self-introduction postings by cancer patients in KDD cancer board? (2) What are other linguistic features of the self-introduction postings by cancer patients in KDD cancer board? (3) What are the psychosocial characteristics of cancer patients that are reflected by these linguistic features?. 1.4 Preview of the Following Chapters In Chapter Two, we review previous literature from five aspects: computer-mediated communication, online health communication, storytelling and narrative medicine, social support for cancer patient, and age-disclosure. In Chapter Three, we introduce the source and collection of our data and also the approach we used to analyze the collected data. In Chapter Four, we present the main findings of the present study. We firstly present the. 4.

(19) finding regarding cancer patients’ age-disclosure (Research Question 1) and then other linguistic features are also presented (Research Question 2). Chapter Five is about the discussion on the arguments generated from the main findings which are also the answers to the third Research Question. In Chapter Six, we firstly summarize the main findings of the present study which is followed by the presentation of implications and limitations of the present study. Suggestions for further studies are then provided and followed finally by the contributions of the present study.. 5.

(20) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW In this chapter, we review the literature related to the present study from five aspects: computer-mediated communication, online health communication, storytelling and narrative medicine, social support for cancer patients and age-disclosure.. 2.1 Computer-Mediated Communication The advancement in computer technology has brought immense transformations to modern society and communication is one aspect that is being affected (Kiesler et al. 1984). Computer-medicated communication is to send messages and have interaction through computer networks to further achieve the function of communication. Moreover, it is an essential component of the emergence of computer networks (Kiesler et al. 1984) and it becomes the major method of communication or even replaces face-to-face communication because of the universality of Internet (Riva 2002). Online communication media for computer-mediated communication include forum, instant messaging, weblog, email, Facebook, bulletin board system (BBS) and so on. Computer-mediated communication is different from traditional face-to-face communication in many ways (Kiesler et al. 1984) and it has the following characteristics. First, computer-mediated communication is conducted mainly in written language (Bordia 1997). Furthermore, because of the persistent nature of written language, message receivers do not need to be present when messages are being transmitted and are able to catch up on the transmitted messages later (Riva 2002). Second, computer-mediated communication makes it possible for its users to communicate without the restrictions of time and place (Spears & Lea 1994). Therefore, a message can be simultaneously. 6.

(21) transmitted all over the world which raises the efficiency of message transmission (Kiesler et al. 1984). Third, in the process of computer-mediated communication, most of the users present themselves in user name so it is difficult to ascertain their real identities (Riva 2002). Moreover, because of the possibility of identity concealment, users are able to express themselves as much as they like without worrying about the impression other users may have on their real identities (Riva 2002), and they can also get the opportunity to equally participate in discussion without the influence of disparity in real social status among users (Kiesler et al. 1984, Bordia 1997).. 2.2 Online Health Communication Because modern people place more and more importance on health, seeking health-related information through Internet has become a trend with the prevalence of Internet and computer-mediated communication. Through survey, Cotten and Cupta (2004) explored the factors which can differentiate online health information seekers and offline health information seekers. Their results show that age is one of the important factors and those who seek health information online are relatively younger (with the average age of 40) compared with those who do not seek health information online (with the average age of 52). Based on the study by Cotten and Cupta (2004), we may infer that those who are under 40 years old may be more likely to seek health information online. Do cancer patients who seek health information through KDD bulletin board system also belong to the average age of 40 or even younger? This is what we would like to investigate through the third research question. Besides, the study by Cline and Haynes (2001) pointed out that through seeking health information online, Internet users can not only get widespread access to information. 7.

(22) and opportunities to have two-way communication but also have increased opportunity to interact with medical professionals and fellow patients. Moreover, they can get access to information on sensitive topics in the anonymous way. People access health information online primarily in three ways: searching directly, consulting with medical professionals and participating in online support groups (Cline & Haynes 2001). Thus it can be seen that people seeking health information online do so not only to fulfill their information need but also to have further communication with medical professionals and fellow patients. How about the cancer patients in KDD cancer board? What is their function or purpose to participant in cancer board and to post self-introduction? This is also what we would like to figure out through the third research question. Because of the popularity of seeking health information online, more and more studies related to interaction or communication focus on health-related information seeking through the Internet. Locher (2006) examined the discourse features and functions of advice-giving in an American Internet health advice column and found that apart from providing advice in the content of response letters to advice-seekers, the advice provider also provided supportive messages, such as providing wishes (e.g. ‘Good luck with your investigation, p.119’). Locher (2006) pointed out that the aim of providing supportive message is to create a connection with advice-seekers and further create rapport between each other. She termed this behavior as ‘bonding.’ As we can see from the study by Locher (2006), certain linguistic features can achieve certain functions. In her case, the linguistic feature of providing supportive messages is used to achieve the function of creating rapport. How about the linguistic features observed from cancer patients’ self-introduction postings? Besides age-disclosure, what might be other linguistic features, and what are their functions?. This is also what we would like to figure out through the third research. question.. 8.

(23) In the present study, cancer patients have online health communication by participating and posting self-introductions in KDD cancer board. As described previously, the content of their self-introduction postings is like their cancer stories, so posting a self-introduction is like telling one’s cancer stories. Thus, we also review literature related to storytelling in health care and narrative medicine.. 2.3 Storytelling and Narrative Medicine Storytelling (i.e. telling one’s own story) has been used as a way to provide care for patients in health care (Chelf et al. 2000). Chelf et al. (2000) held a storytelling workshop for cancer patients, their family members and people from the public. Three months after the workshop, they emailed evaluation sheets to the participants. According to the evaluation from workshop participants, 97% of them agreed that storytelling is an effective strategy for dealing with cancer because cancer patients are able to transmit cancer-related information and hope, create connection with each other and promote their understanding about themselves by telling their own stories. In addition, 85% of the participants agreed that they obtain hope through the process of listening to others’ cancer stories. Høybye et al. (2005) analyzed the personal cancer stories shared through a breast cancer mailing list and also interviewed the breast cancer patients who were in the list. Their results showed that breast cancer patients were able to obtain encouragement and know how to live with cancer through reading other cancer patients’ stories. Moreover, when playing the role of storytellers, cancer patients can get a new identity different from the ones in medical contexts where they are being passively acted upon. Now we have known the advantages of telling one’s own story or listening to other’s story from patient’s perspective. How about the significance of listening to patients' stories. 9.

(24) from a doctor’s perspective? Charon (2001b) argued that medicine which only emphasizes medical skill may undermine the importance of realizing patients’ suffering and the contexts they are in. Therefore, she brought up the concept of narrative medicine. That is, as she described, to practice medicine with narrative ability to understand, recognize and interpret the situation others’ are in. Through listening to patients’ stories, doctors are able to imagine the situations their patients are in and further enter the world of the patients, and therefore doctors can establish therapeutic relationships with their patients, experience and communicate empathy for patients’ experiences and further help patients to get effective care (Charon 2001a). Greenhalgh and Hurwitz (1999) also mentioned that understanding the contexts of patients’ stories enables their doctors to comprehensively approach their problems and find the therapeutic options suitable for them. We can conclude from the above studies that listening to and conveying empathy for patients’ narratives on their illness experiences and mental processes they went through is the basis of the creation of connection with patients and also the basis of the provision of treatment to patients. Because of the increasingly popularity in using storytelling as a tool to provide care for patients in health care and the importance of understanding patients’ stories in order to provide them with better care, studies that focus on personal illness narratives can provide great insights into getting a better understanding of patients. Chou et al. (2011) collected the personal cancer narratives (i.e. stories told by cancer patients regarding their illness) posted on YouTube and analyzed their linguistic features as well as their functions. In the cancer stories they collected, they found the presence of temporal orientation, such as explicit mentioning of time, like time relative to the narrator’s life (e.g. ‘the day before my 30th birthday,’ e7), and memorable life events surrounding the event of receiving a cancer diagnosis. Apart from temporal orientation, Chou et al. (2011) also found another feature: description of a sense of normalcy. This feature is marked with the use of positive. 10.

(25) descriptors and emphatic adverbials, such as, “great” and “never even”, respectively. We have mentioned that cancer patients’ self-introduction postings in KDD cancer board can be said to be their personal cancer stories. Can we find similar linguistic features observed in the study by Chou et al. (2011) in cancer patients’ self-introduction postings? This is what we would like to figure out through the second research question.. 2.4 Social Support for Cancer Patients Kyngäs et al. (2001) interviewed 14 young cancer patients from ages 16 to 22 and investigated the strategies they used to deal with cancer. They found that the primary strategy their interviewees employed is social support. Those young cancer patients used emotional and informational support from family members, friends, fellow patients and medical professionals to confront cancer. Rodgers and Chen (2005) examined the psychosocial benefits breast cancer patients can receive through participation in an online breast cancer discussion board by analyzing the postings posted in it. One of the psychosocial benefits they pointed out was giving and receiving social support. They found in the postings they analyzed that numerous breast cancer patients indicated the enjoyment of being able to provide support for one another and of receiving support from others. Based on the research by Kyngäs et al. (2001) and Rodgers and Chen (2005), we can infer that the obtainment of social support is very important for cancer patients. Klemm et al. (1998) also stated that cancer support groups are created because cancer patients can benefit from the interaction with other cancer patients. Participants of cancer support groups get together to provide mutual support, exchange information and share experiences, and they are usually cancer patients and relatives and friends of cancer patients (Klemm et al. 1998). By participating in support. 11.

(26) groups, patients can not only receive emotional support from fellow patients but also adopt others’ experiences to deal with their own unknown future because the major advantage of participating in support groups is to get support and feedback from fellow patients (Weis 2003). Different from traditional face-to-face support groups, online support groups are available 24 hours and participants of online support groups can participate in the groups and have interaction with participants all over the world at home at any time they are available (Klemm et al. 1998, Weinberg et al. 1996). Im (2011) reviewed the literature related to Internet cancer support groups and came up with five factors which influence the use of Internet cancer support groups: disease factors, background factors, cultural factors, need factors and Internet use factors. With regard to background factors, Im (2011) found that those who obtain cancer related information online are more likely to be younger. Moreover, those who get used to searching information through the Internet have the tendency to turn to Internet for help when they are in need of cancer related information and they also tend to use Internet cancer support groups for getting emotional support. Thus, active participants in Internet cancer support groups are also active Internet users. Based on the study by Im (2011), we can infer that when Internet users get used to searching information via Internet, they will also use Internet for other functions and purposes, such as, having social interaction. Searching information related to their condition and getting support from support groups through Internet are two of the functions cancer patients are in need of.. Since our preliminary finding has shown that cancer patients in KDD cancer board tend to disclose their own age spontaneously, we review the literature related to age-disclosure in 2.5.. 12.

(27) 2.5 Age-Disclosure Coupland et al. (1989) investigated the communication pattern between elderly people and young adults. They arranged for 20 elderly people (aged 70 to 87) and 20 young adults (aged 30 to 40) to have intergenerational conversation (one elderly person paired with one young adult). The elderly people and young adults who participated in their study did not know each other prior to their participation in the research and were asked to get to know each other only through conversation. After analyzing the conversations, Coupland et al. (1989) found the disclosing of chronological age in 15 out of the 20 conversations, and in over half of the cases (12), disclosing of the elderly’s chronological age was done by elderly people themselves. Age-disclosures by young participants in the other three cases were either the result of the alignment with elderly people’s children or an inquiry from the elderly. In the same research, Coupland et al. (1989) also interviewed 40 elderly people individually. During the interview, 32 (80%) out of the 40 elderly people spontaneously disclosed their own age when they were asked questions related to the experiences of health care, such as, ‘How is your health generally?’ (p.134). Based on their research results, Coupland et al. (1989) considered the discourse pattern of age-disclosure from elderly people to be closely related to health and aging because the socially agreed association between aging and decrement can be reflected from the pattern of age-disclosure from the elderly people, such as, ‘I’m seventy…this October so I find I can’t do it so good’ (p.135). Therefore, they argued that age-disclosure is not merely to reveal personal information; it is also a way to pursue some particular aims. For example, age-disclosure can be a way to rationalize one’s health degeneration (e.g. ‘oh not very good (.) well I’m almost eighty and I can’t expect much,’ p.136) or to give positive evaluation on one’s physical condition (e.g. ‘mind I’m gone eighty I’m going eighty one! … and I think I’m pretty good,’ p.137). 13.

(28) Coupland et al. (1989) proposes that there are two kinds of age: chronological age and contextual age. Chronological age is one’s real age so it is predictable based on his/her birth year. Contextual age, on the other hand, is unpredictable and may be changed according to one’s physical or mental circumstances, such as, being ill. For most people, there is a preference to delay the progress of both chronological and contextual age. However, there is a tendency for one’s contextual age to be younger than his or her chronological age because the passing of time is inevitable. Coupland et al. (1989) further stated that the meaning and function of age-disclosure correlate closely with the relationship between chronological and contextual age. They argued that if one conceived that his/her mental age was congruent with his/her chronological age and positively evaluated his/her physical condition, age-disclosure did not imply any particular significance other than revealing one’s basic information. Therefore, age-disclosure is unlikely to be observed in this situation (p.139). On the other hand, if one conceived that his/her mental age was congruent with his/her chronological age but negatively evaluated his/her physical condition, age-disclosure in this situation was used to rationalize one’s health degeneration (p.136). To consider it another aspect, age-disclosure serves to get rid of the association between aging and health degeneration if one conceived that his/her mental age was younger than his/her chronological age and positively evaluated his/her physical condition (p.137). Conversely, if one conceived that his/her mental age was older than his/her chronological age and negatively evaluated his/her physical condition, the action of age-disclosure, then, is highly face-threatening. That is because age-disclosure in this situation is equal to the acknowledgement of ‘I’m bad for my age’ (p.139). In the self-introduction postings analyzed in the present study, most of the cancer patients in KDD cancer board also spontaneously disclose their age within posting content. What is the function of age-disclosure in self-introduction postings by cancer patients? Is there any. 14.

(29) similarity between the age-disclosure in self-introduction postings by cancer patients and the situation stated by Coupland et al. (1989)? This is also what we would like to figure out through the third research question.. 15.

(30) CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY In this chapter, we introduce the source and collection of our data (3.1) as well as the way we analyze the collected data (3.2).. 3.1 Data Collection The data examined in the present data are postings in Bulletin Board System (BBS). Bulletin Board System is a kind of online forum. Its distinctive feature is to provide forums for different topics and free two-way communication; that is, every user is both reader and writer. The BBS chosen for the present study is the most famous and widely used one in Taiwan at present, named KDD. It was founded by the students from the Department of Information Engineering of a university in northern Taiwan in 1995 and up to now, it is still administrated by that school. KDD provides a free, rapid, open and real-time platform for discussion. It is divided into different boards in accordance with different topics and has about 6,000 boards in total, including sports, politics, travel, food and jobs. There is no restriction on user registration in KDD, but most users are young people, ranging roughly from high school students to those in their 30s. Up to November 4, 2012, the total number of those who registered in KDD was more than one million and five hundred thousand. The data for the present study was collected from KDD cancer board. The members of this board are mostly cancer patients (‘patient member’ hereafter) and relatives and friends of cancer patients (‘non-patient member’ hereafter). They come here to share experiences as well as medical news, express emotions or seek other members’ opinions and suggestion on their questions about diagnosis and treatment. Up to July 25, 2012, there were 11,683 postings in KDD cancer board. For ease of categorization, titles of the postings in cancer. 16.

(31) board are labeled with keywords for categorization, such as, ‘問題/question’, ‘新聞/news’ and ‘自介/self-introduction.’ The posting labeled with ‘自介/self-introduction’ is usually the first posting from members in the cancer board or their first time to introduce themselves officially (cf. Examples 3.1 and 3.2). Apart from cancer patients, those who post self-introduction in the cancer board may be relatives and friends of cancer patients. However, because the present study focuses on psychosocial characteristics of cancer patients, self-introduction postings by non-patient members are not included in the process of data collection. We use ‘自介/self-introduction’ as a keyword to search the postings labeled with ‘ 自 介 /self-introduction’ in the KDD cancer board and got 166 self-introduction postings in total. After skimming through their posting content, we excluded the self-introduction postings by non-patient members (108 in total) and got 58 self-introduction postings by patient members. As shown in Table 3.1 which presents the demographic information for these 58 patient members, the time of posting of these 58 self-introduction postings dates from October 29, 2005 to June 29, 2012 and the types of cancer these 58 patient members had amounts to more than ten. Among them, lymphoma takes up the highest percentage (21%), leukemia the secondary high (16%), and breast cancer (16%) the third high.. Table 3.1 Demographic information for the 58 self-introduction postings by patient members. ID. Time of posting. Reported age. Reported gender. Type of cancer gotten. 1. Ka. 2012/06/29. 27. Male. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 2. P. 2012/03/29. 26. Female. Lymphoma . 3. B9. 2012/03/10. 25. Not mentioned. Lymphoma. 4. Hu. 2012/01/17. 23. Male. Lymphoma. 5. Fi. 2012/01/06. 21. Male. Leukemia. 17.

(32) 6. Fa. 2011/12/22. 26. Male. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma . 7. Cu. 2011/10/27. 30. Female. Breast cancer. 8. Lo. 2011/10/26. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Colorectal cancer. 9. Po. 2011/10/23. 29. Male . Bone cancer. 10. Mu. 2011/10/06. 35. Male . Kidney cancer. 11. Al. 2011/06/22. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Leukemia . 12. Ya. 2011/06/17. 26. Female. Breast cancer. 13. Mi. 2011/02/28. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Leukemia . 14. Co. 2010/12/28. 20;18*. Female. Bone cancer . 15. Su. 2010/06/28. 28;15*. Not mentioned. Leukemia. 16. Kas. 2010/04/06. 33. Female . Breast cancer. 17. Ph. 2010/04/02. 27. Female . Breast cancer. 18. Gi. 2009/12/14. 27. Female . Endometrial cancer. 19. Se. 2009/12/14. 19. Female . Lymphoma. 20. Au. 2009/11/29. 22. Female . Ovarian cancer. 21. Rc. 2009/10/12. 22. Female . Ovarian cancer . 22. Coo. 2009/10/01. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor. 23. Tw. 2009/09/21. 21. Male. Colorectal cancer. 24. Ts. 2009/08/07. 27. Female. Breast cancer. 25. Af. 2009/05/27. 17. Not mentioned. Lymphoma. 26. Ch. 2009/04/03. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Leukemia. 27. Ku. 2009/03/20. 27. Female. Cerebellar cancer. 28. Ba. 2009/02/17. 25. Male. Colorectal cancer. 29. En. 2008/12/07. 25. Female. Lung cancer. 30. Ni. 2008/11/25. 23. Not mentioned. Lymphoma. 31. El. 2008/11/14. 35. Male. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 32. Bl. 2008/09/26. 24. Not mentioned. Tongue cancer. 33. Vi. 2008/09/19. Not mentioned. Female. Breast cancer . 34. Ma. 2008/06/19. 23. Not mentioned. Osteosarcoma. 35. L. 2008/05/19. Not mentioned. Female . Breast cancer. 36. Es. 2008/05/16. Not mentioned. Female . Breast cancer . 37. B. 2008/03/05. 24. Male. Leukemia . 18.

(33) 38. Vm. 2008/01/12. 24. Female. Endometrial cancer. 39. Lu. 2007/10/10. 25. Not mentioned. Leukemia. 40. Mo. 2007/10/06. Not mentioned. Not mentioned. Lymphoma. 41. Sc. 2007/05/01. 25. Not mentioned. Lymphoma. 42. Pol. 2007/03/01. 28. Not mentioned. Lung cancer . 43. Pa. 2006/10/12. 23. Male . Thyroid cancer. 44. Ja. 2006/09/20. 20. Male . Lymphoma. 45. An. 2006/09/04. 23. Male . Testicular cancer. 46. Sn. 2006/08/31. 15. Not mentioned. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 47. Kk. 2006/08/29. 24. Female . Lymphoma. 48. St. 2006/08/23. 23. Female . Breast cancer. 49. Min. 2006/08/07. 18. Not mentioned. Osteosarcoma . 50. Am. 2006/04/25. 21. Not mentioned. Leukemia. 51. Ki. 2006/01/21. 27. Male. Soft-tissue sarcoma. 52. Jam. 2005/12/19. 23. Male . Colorectal cancer. 53. Di. 2005/11/02. 46. Female. Tongue cancer . 54. Ws. 2005/11/02. 28. Male . Leukemia . 55. Re. 2005/11/01. 27. Male . Lymphoma. 56. Cc. 2005/10/29. 24. Male . Testicular cancer . 57. Sa. 2005/10/29. 27. Female . Lymphoma. 58. C. 2005/10/29. 22. Female . Nasopharyngeal carcinoma . *These two patient members presented both their age at the time they posted self-introduction and their age at the time of their cancer diagnosis.. 3.2 Data Analysis We examined the contents of self-introduction postings from the perspective of discourse analysis. Discourse is a part of language use which can be either in oral or in written form and its length ranges from a discourse marker, full sentence, to a narrative of personal experience (Sherzer 1987). According to Sherzer (1987), there is a wide variety of sources. 19.

(34) of discourse, for example, transcription of interviews, samples of conversations, media and web based materials. The self-introduction postings examined in the present study are a kind of discourse because they are a written form of personal experiences and they are from a bulletin board system, an online medium. Discourse analysis is to study and analyze language use (Hodges et al. 2008). It starts from the analysis of the text of an interaction. Through analyzing its discourse elements, from word usage and sentence pattern to choice of language and discourse structure, discourse analysis provides an in depth understanding of the pragmatic function of language use (Mishler 1991, Roberts & Sarangi 2005, Hodges et al. 2008). Because discourse generates from actual instances of language use, it should also be interpreted with consideration of its contexts (Sherzer 1987). By understanding the local circumstances and contexts of the discourse under examination, we will be able to discover the ideologies and beliefs participants unconsciously bring to the interaction (Roberts & Sarangi 2005). Hodges et al. (2008) also mentioned that we should not understand the meaning of a discourse merely at the semantic level but should do it at a higher level. Therefore, to interpret the collected data, we focus not only on the linguistic features of cancer patients’ accounts but also pay attention to the relevant social or contextual background the discourse is taken from (i.e. KDD cancer board) and also how the linguistic features correlate to such background information and discourse participants. There are many approaches to discourse analysis and Hodges et al. (2008) simplified them into three types: formal linguistic discourse analysis, empirical discourse analysis and critical discourse analysis. What is employed in the present study is closer to empirical discourse analysis. To seek functions of language use, empirical discourse analysis puts more emphasis on sociological uses of language and its aim is to interpret how the meaning of the language is conveyed by the language users (Hodges et al. 2008). Hodges. 20.

(35) et al. (2008) further stated that discourse analysis is an effective method for research related to health care and the health professions. Thus, we employ this approach in order to figure out the psychosocial characteristics of cancer patients that are reflected by the language they use. To sum up, discourse analysis is conducted to figure out the mode of discourse (how it is said) by analyzing the text of an interaction (what is said) and to further understand the function interaction participants would like to convey or cultural and psychosocial characteristics reflected in the interaction of interaction participants. We use Examples 3.1 and 3.2 presented below to briefly exemplify how we code the collected data. Sentence segmentation of the postings is based on the patient members’ original segmentation. These two patient members’ disclosed their age-related information through Line 18 in Example 3.1 and Line 2 in Example 3.2, respectively. Thus, these two lines were coded as instances of age-disclosure. The patient member in Example 3.1 mentioned her wonderful life prior to the cancer diagnosis in Lines 2 to 5 and thus these lines were coded as instances of description of the sense of satisfaction with life prior to the cancer diagnosis. Moreover, through Line 1, this patient member indicated that the membership in KDD cancer board was unexpected to her and thus it was coded as an instance of a description of the counter-expectation of getting cancer diagnosis. Besides, this patient member contained the phrase ‘加油/go for it’ in the last line, Line 41, as an encouragement and thus it was coded as an instance of words for encouragement.. Example 3.1 Self-introduction posting by one of the patient members in KDD cancer board. 標題. [自介] 焉知非福?!. Title. [self-introduction] A blessing in disguise?!. 21.

(36) 1. 好吧!我得承認,其實自己從來沒想過得要來這個版做自介:( ‘Well! I have to confess that in fact I have never even thought that I would have to come to this board to do self-introduction :(’. 2. 在一個月前,老娘我還是個天之嬌女。 ‘A month ago, I was still in very good condition, just like the dearest daughter of God.’. 3. 剛在國外念完我的第二個碩士,在倫敦知名的時尚產業找到工 作, ‘Just got my second master’s degree abroad, found a job in famous fashion industry in London.’. 4. 每天在設計師與精品中打轉,唯一需要想的是下個 party 要穿什 麼, ‘Everyday stayed with designers and fashion goods, the only thing I needed to think was what I should wear to the next party’. 5. 開開心心地請假回台灣過農曆年... ‘Joyfully asked for a leave for coming back to Taiwan during Chinese New Year …’. 6. 我想,其實上帝很眷顧我。 ‘I think in fact God has mercy on me.’. 7. 我沒有摸到腫瘤,也沒有任何的不舒服, ‘I did not touch any tumor, neither have any discomfort.’. 8. 但我做了個夢,夢到自己得了乳癌,夢境實在太真實,醒來我在 和夢裡同個地方, ‘But, I made a dream. I dreamed that I got breast cancer. The dream was too real that after I woke up in the same place as in the dream’. 22.

(37) 9. 我摸到了。 ‘I feel it.’. 10. 一開始去義清觸診,心裡還老大不願意,畢竟網路上都說有 80% 都是良性的, ‘In the first place I went to Yi Qing1 for palpation but I was in fact unwilling to go because on the Internet it is said that 80% is benign.’. 11. 人都是這樣,總是會想,我沒那麼倒楣吧?! ‘Human beings is always like this, always think that I am not so unfortunate, right?!’. 12. 但真的是因為我的夢,我還是硬著頭皮去了... ‘But it was really because of my dream; I still forced myself to go to the hospital.’. 13. 過程很快,乳房超音波看得很清楚,細針穿刺後也證實是惡性腫 瘤。 ‘The process went through quickly, it was very clear through ultrasonic mammography; after fine-needle aspiration it was also verified to be a malignant tumor.’. 14. 過程可以用幾句話帶過,但心情可不是這樣! ‘The process can be explained in a few sentences but my mood is not!’. 15. 從小我就愛面子,在醫生面前我沒有哭,很堅強的問了所有我知 道的問題: ‘I am so sensitive about my reputation from my childhood that I did. 1. pseudonym for a hospital in northern Taiwan . 23.

(38) not cry in front of the doctor but hardily asked every question I know:’ 16. 手術什麼時候做?腫瘤有多大?以後治療的方式有哪些? ‘When should I undergo operation? What is the size of the tumor? What are the treatments afterwards?’. 17. 回家後抱著媽媽,不知道哭了幾天,不斷地問著媽媽... ‘After I returned home, I hugged my mom and did not know for how many days I cried and kept asking my mom…’. 18. 為甚麼會是我?我才 27 歲!!家裡沒有遺傳,我也不符合高危 險群,為甚麼會是我?! ‘Why me? I am only 27!! It is not hereditary in my family and I am not from high-risk populations. Why me?!’. 19. 媽媽說,其實你很幸運,如果繼續待在國外,以妳的個性一定懶 得去看醫生, ‘My mom said that in fact you are very lucky, if you kept staying abroad, according to your personality, you must be too lazy to go to see a doctor.’. 20. 拖到後來都不知道會有多嚴重了,要換個方向想!碰到了就只能 去面對它! ‘You will not know how serious it might be if you kept putting it off. You have to think it in another way! Once you ran into it, you have to face with it!’. 21. 爸爸也說,錢不是問題,就算是賣房子,爸爸也一定會給你最 好的! ‘My dad also said that money is not a problem, even if I have to sell. 24.

(39) house, daddy will definitely provide you with the best!’ 22. 有家人的支持,心裡真的會放心很多,謝謝爹地媽咪:) ‘With family’s support, I can really set my mind at ease. Thanks daddy and mommy:)’. 23. 在義清要切片時,當我躺在手術台上醫生竟然說,腫瘤還很小, 我看乾脆直接拿掉吧! ‘When I was doing biopsy at Yi Qing and lying on the operating table, the doctor, to my surprise, said that the tumor is still very small. Let me just take it away!’. 24. 結果,造成之後改去漲生做前哨淋巴切除手術時,還被醫生再切 了一次怕之前沒切乾淨 ‘As a result, after I transferred to Zhang Sheng2 and underwent sentinel lymph node dissection, the doctor there being afraid that there were still something remained did biopsy again.’. 25. 昨天手術後複診順便看報告, ‘Yesterday I had a subsequent visit after the operation and also read the report.’. 26. 期數是 t1c (c 又是代表什麼呢?),前哨淋巴拿了兩顆都沒有感 染:) ‘Stage is t1c (What does c mean?) and the two sentinel lymph node taken out were not infected:)’. 27. tumor size 1.6*1.4*1.2cm ‘tumor size 1.6*1.4*1.2cm’. 28. tumor grade: score:6 nbr grade: 2 (這個是什麼意思呢). 2. pseudonym for a hospital in northern Taiwan . 25.

(40) ‘tumor grade: score:6 nbr grade: 2 (What does this means)’ 29. ER(3+, 90%), PR(-,<2%), HER-2-NEU(3+) ‘ER(3+, 90%), PR(-,<2%), HER-2-NEU(3+)’. 30. 但由於腫瘤再義清時已被拿光,漲生的腫瘤醫生又不信任義清的 切片結果, ‘Because the tumor was clearly taken out in Yi Qing and the doctor in Zhang Sheng did not trust the result of biopsy from Yi Qing,’. 31. 所以還得等到最後 FISH 出來後才能決定最後的治療方法:( ‘I have to wait for the result of FISH in order to decide what eventually will be the treatment:(’. 32. 但稍微有和醫生討論一下,如果真的是 her2 neu3+的話, ‘But I have slightly discussed with the doctor, if it is true that it is her2 neu3+,’. 33. 就是四次小紅莓+四次紫杉醇+五個禮拜的電療和一年的賀癌平 ‘the treatment will be Doxorubicin for four times + Taxol for four times + electrotherapy for five weeks and Herceptin for a year.’. 34. 這些全部都得自費! ‘I have to pay for all of these at my own expense!’. 35. 我的疑問是...如果真的只是第一期,有必要做到八次的化療嗎? ‘My question is … if it is really just in stage 1, do I need to undergo chemotherapy for eight times?’. 36. 這樣的治療方式那和已經擴散出去的應該沒有什麼差別了 吧?! ‘This kind of treatment is nothing different from the treatment for the cases of metastasis, right?!’. 26.

(41) 37. 另外,我知道標把健保沒有給付,但連小紅莓和紫杉醇也沒有 嗎? ‘Besides, I know that NHI does not pay for targeted drug but is it true that they also do not pay for Doxorubicin and Taxol?’. 38. 我不是個很樂觀的孩子,但總希望可以和媽咪說得一樣,塞翁 失馬焉知非福, ‘I am not an optimistic child but I hope it will be just like what mommy said a setback may turn out to be a blessing in disguise.’. 39. 希望這次生病,能夠改變我的生活作息和飲食習慣,也是一件好 事:) ‘I hope the experience of falling ill can change my lifestyle and dietary habit and that will be a good thing:)’. 40. 現在每天都乖乖地三餐正常和運動!希望接下來面對化療可以 也一切順利! ‘Now I obediently have normal meals and exercise everyday! Hope the following chemotherapy will go smoothly as well!’. 41. 大家一起加油吧!!! ‘We can do this!!!’. Example 3.2 Self-introduction posting by the patient member who took the lead in writing in listing format. 標題. [自介] 病友一號小金剛報到. Title. [self-introduction] fellow patient no. 1 Little King Kong check in. 1. ID︰C (女) ‘ID: C (female)’. 27.

(42) 2. 年齡︰22 ‘Age: 22’. 3. 所在地︰新竹 ‘Location: Hsinchu’. 4. 病名︰鼻咽癌併發骨轉移(第 IV-c 期) ‘Name of disease: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with bone metastasis (in the stage of IV-c)’. 5. 治療方式︰四年前放療 41 次+化療 3 次、一年前轉移至大腿骨化 療半年無效, ‘Way of treatment: four years ago, I underwent radiation therapy for 41 times + chemotherapy for 3 times and a year ago, it had metastasized to thighbone and so I underwent chemotherapy for half a year but in vain.’. 6. 局部放射 1X 次、然後在今年五月發現再度轉移至脊椎附近, ‘Partial radiation therapy for 1X times and then this May it was found to metastasize again to nearby spine.’. 7. 三個化療療程無效,改用局部放射 11 次,現在休息等待下次化 療。 ‘Three courses of chemotherapy were in vain so it is changed to partial radiation therapy for 11 times, now I am taking a rest to wait for next chemotherapy.’. 8. 就醫所在地︰漲生腫瘤科 放射腫瘤科 ‘Place for taking medical treatment: Division of Oncology and Division of Radiation Oncology in Zhang Sheng’. 9. 目前狀態︰閒閒沒事在家發發燒修養中。. 28.

(43) ‘Present condition: fooling around and staying at home, having fever and taking a rest’ 10. 目標︰再活個幾十年,環遊世界當浪人。 ‘Goal: to be alive for ten more years and traveling around the world to be a vagrant’. 11. 註備︰目前我只想得到這些,大致上這樣應該就好了吧?有想到 再補上來, ‘Remarks: at present I can only think of these, it is enough in substance, right? I will add more information if I think of any other’. 12. 還有人有什麼建議的話,盡量表示喔! ‘If anyone has any suggestion, please bring it up as much as possible!’. 13. 家屬的話,請不只介紹你的家人,也多介紹自己本人喔。 ‘If you are family members of cancer patients, please not only introduce your family members but also introduce more about yourselves.’. 14. 還有我也是第一次當版主,很多不懂,也請多多指教。 ‘And, it is also my first time to be the host of a board, there are many things I do not understand and please kindly give me your advice.’. 15. 小的心路歷程請洽︰(the link to C’s personal weblog is taken off here) My experiences please refer to: (the link to C’s personal weblog is taken off here). 29.

(44) In order to strengthen our arguments and make them more valid, we make some comparison and provide some other related information. They will be mentioned later in the sections they correlate to. Besides, we have to declare that because interaction on the Internet is not face-to-face and identities of Internet users do not necessarily reflect those in real life, we can never be sure regarding the real social characteristics of the members in BBS (Riva 2002), such as, gender, age, level of education and so on. Therefore, our analysis of social characteristics of members in KDD cancer board is simply based on the information presented or constructed in the members’ self-introduction postings.. 30.

(45) CHAPTER FOUR FINDINGS In this chapter, we present our three major findings: (1) age-disclosure (2) normal and wonderful life prior to cancer diagnosis (3) words for encouragement.. 4.1 Age-Disclosure After reading through the self-introduction postings from patient members, we found that 49 out of the 58 patient members (84%) spontaneously mentioned their own age or the year they were born. The age they mentioned was either age at the time of posting (‘age at posting’ hereafter) or age at the time of their cancer diagnosis (‘age at cancer diagnosis’ hereafter). There were also cases where both of them were mentioned. We found that the linguistic pattern for age-disclosure can be divided into six types. Table 4.1 shows the number of times, percentage and examples of each type from our collected data. Most of these 49 patient members mentioned their age-related information only once within their posting content. However, three of them mentioned twice and thus the total number of times each types used (52) is more than 49. The first three types, stative, prospective and retrospective, are adopted from Coupland et al. (1989). According to them, age was reported as a state in stative format (e.g. ‘我今年 26 歲/This year I am 26.’). Also according to Coupland et al. (1989), prospective format and retrospective format report age as a developmental process. For the sake of better understanding, we define prospective format as reporting future age in future tense, such as, ‘下星期六 我要過 23 歲生日/Next Saturday I am going to have my 23rd birthday.’ and define retrospective format as reporting the age at that time reflectively like doing a review, such as, ‘發病的那一年 我才 15 歲/In the year I got cancer, I was only 15 years old.’ Type four to six are new patterns observed. 31.

(46) from our collected data. The forth type is listing format in which age is listed as an item in a list like ‘年齡:23/Age: 23.’ The fifth type is direct format in which age or the year they were born is mentioned neither with a sentence subject nor under an item in a list. (e.g. ‘74 年次(26 歲) 男性/Born in 1985 (26 years old) male’). The last one is indirect format. In this type, members did not explicitly mention their age but mentioned it indirectly within the content of self-introduction posting, such as, ‘第一次發現的時候(23 歲)是第二期 /When it was first discovered (23 years old), it is in second stage.’ As it is shown in Table 4.1, listing format was used with the highest percentage (38%).. Table 4.1 The number of times each type of age-disclosure format was used. Type of format. Number of times. Percentage. Stative. 9. 17%. Prospective. 3. 6%. ‘Next Saturday I am going to have my 23rd birthday.’ 發病的那一年 我才15歲. Retrospective. 5. 10%. Listing. 20. 38%. ‘In the year I got cancer, I was only 15 years old.’ 年齡:23. Direct. 8. 15%. Indirect. 7. 14%. Total. 52. 100%. Examples from the collected data 我今年26歲 ‘This year I am 26.’ 下星期六 我要過23歲生日. ‘Age: 23’ 74年次(26歲) 男性 ‘Born in 1985 (26 years old) male’ 第一次發現的時候(23歲)是第二期 ‘When it was first discovered (23 years old), it is in second stage.’. We also found that listing format and direct format both present age-related. 32.

數據

相關文件

Estimated resident population by age and sex in statistical local areas, New South Wales, June 1990 (No. Canberra, Australian Capital

As we shall see later (Corollary 1 of the global Gauss-Bonnet theorem) the above result still holds for any simple region of a regular surface.. This is quite plausible,

• Three uniform random numbers are used, the first one determines which BxDF to be sampled first one determines which BxDF to be sampled (uniformly sampled) and then sample that

Consequently, these data are not directly useful in understanding the effects of disk age on failure rates (the exception being the first three data points, which are dominated by

People of lesser capacities had to learn Hinayana teachings first in order to increase their intellectual power before they turned to Mahayana; the result was the gradual doctrine.

根據國民健康署統計資料顯示,食道癌 發生率在台灣地區每年約有 2000 多名新 病例發生,於 2017

The oxidation number of oxygen is usually -2 in both ionic and molecular compounds. The major exception is in compounds called peroxides, which contain the O 2 2- ion, giving

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it