Do founders’ own resources matter? The influence of business networks on

start-up innovation and performance

Hao-Chen Huang

a,n, Mei-Chi Lai

b, Kuo-Wei Lo

ca

Graduate Institute of Finance, Economics, and Business Decision, National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, No. 415, Chien Kung Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan, ROC

bInstitute of Health Policy and Management, National Taiwan University, 6F., No.17, Syujhou Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan, ROC c

Graduate Institute of Finance, Economics, and Business Decision, National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, No. 415, Chien Kung Road, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan, ROC

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Available online 20 January 2012 Keywords:

Business networks Founder’s human capital Founder’s ties

Organizational innovation

a b s t r a c t

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the potential influence of founders’ ties and human capital on organizational innovation and organizational performance. In addition, this study determines whether or not business network mediates the relationship among contextual variables. Accordingly, this work devises a hypothesized model for exploring the links among contextual variables. Accord-ingly, in the conceptual model, business network is conceptualized as a second-order construct comprised of three complementary first-order dimensions: supplier interaction, customer interaction, and competitor interaction. To clarify the relationship among these variables, structural equation modeling (SEM) is used to examine the hypothesized model’s fit and the hypotheses. Using data from a study of 222 start-ups’ founders sampled from China-based Taiwanese small and medium enterprises, the result of SEM clearly demonstrates the mediating role of business network in the relationship between founders’ ties and both organizational innovation and firm performance, as well as in the relationship between founders’ human capital and both organizational innovation and firm perfor-mance. Moreover, this paper illustrates the role of business network in the organizational innovation and organizational performance enhancement through empirical evidence from China-based Taiwa-nese small and medium enterprises, which makes a contribution to the current literature.

&2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

A review of the literature on social capital suggests two major themes: (1) how to connect an actor with a network in possession of specific resources; (2) how an actor uses his network structure to construct advantageous social capital. Both themes emphasize the strong relationship between social capital and network structure. A social network is regarded as a web of personal relations which provides powerful means and channels of access to information and resources (Lin and Si, 2010). Accordingly, social capital is the shared resource embedded within social networks. Having different ties, each individual will be able to connect different information and resources. Therefore, social capital can be regarded as a relational resource (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Expanding individual social network to organizational network will create meaningful ties for the organization to connect mutual networks (or business networks) and bring important resources that used to be non-imitable and inaccessible (Ahuja, 2000a;Burt, 1992; Granovetter, 1985; Pfeffer

and Salancik, 1978;Uzzi, 1996). Such business networks may come from alliance, cooperation and mutual investments among organi-zations (Brass et al., 2004;Santos and Eisenhardt, 2009). Or they may come from interaction with suppliers, customers and compe-titors (Gem ¨unden et al., 1996; Kajikawa et al., 2010; Tolstoy and Agndal, 2010). Business networks can help lower transaction costs (Martin and Eisenhardt, 2010), obtain organizational core resources and strategic assets (Andersson et al., 2002), facilitate organizational dynamic learning (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000), or facilitate organiza-tional innovation (Barge-Gil, 2010;Naranjo-Gil, 2009). Based on the above, we know a variety of advantages business networks bring to an enterprise and help bolster up its competitiveness. Since the speed of technological innovation and market vagaries is ever increasing, companies, when faced with external competition and pressure, must expand their own competitive advantages aggres-sively and obtain core capabilities and resources through growing interaction with other business networks. However, how to achieve so in order to innovate an organization and enhance its performance (Gomes-Casseres, 1996) is a problem facing an enterprise sooner or later. Since new companies would encounter fiercer competition than established organizations, it is extremely important for new companies, small and medium enterprises in particular, to manage their business networks. Therefore, it is one of the research motives Contents lists available atSciVerse ScienceDirect

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/technovation

Technovation

0166-4972/$ - see front matter & 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2011.12.004

n

Corresponding author. Tel.: þ886 7 3814526; fax: þ886 7 3836380. E-mail addresses: haochen@cc.kuas.edu.tw (H.-C. Huang),

to explore the influence that the business networks of a start-up have on organizational innovation and performance.

Some scholars point out that an organization would consider the current networks and organizational types when choosing potential ties and networks for the future (Walker et al., 1997). In other words, the past ties of an organization would bring significant implications for the new ties (Baum et al., 2005; Gulati, 1995;

Podolny, 1994). And the new ties are mostly those who they worked with before or those whose types are similar (Gulati, 1995;Podolny, 1994). However, there are few research studies on how start-ups establish their networks and positions and thereafter bring them-selves more ties and margin growth (Hallen, 2008). Logically, the ties and human capital that start-up founders develop should be able to determine the initial network positions of the organizations (Hallen, 2008). After all, start-up companies have insufficient resources in the inception of their operation. They tend to take advantage of their own resources, such as the founders’ own ties and human capital. Therefore, the study, which focuses on founders’ social capital, explores the correlation between founders’ ties and human capital and their business networks. That is the second motive of the research study.

In a Chinese society, social capital is embedded in the social network composed of a wide variety of social relations (Lin et al., 2009). A start-up founder takes advantage of social relations in exchange of the resources the company wants. Therefore, the research, based on the perspective of social capital and network interaction, explores how the ties and human capital of a start-up founder influences organizational innovation and performance, as well as the role a business network plays. The research purposes are as follows: (1) the study uses a second-order factor model to analyze the construct of business network and to discuss whether a business network reflects supplier interaction, customer interaction and competitor interaction for further research and analysis. That is, it is to construct the validity and measurement of the network dimensions, and to decide which kind of interaction is the most important for a up. (2) The research investigates how a start-up relies on the founder’s ties and human capital to form the initial business network and position, and thereby enhances the innova-tion capability and performance. That is, it is to explore whether mediating effects of a business network exist.

As for the structure of the study, the next section will briefly review relevant theories and literature, including social capital and business networks, together with research hypotheses. Then, it will illustrate the research method, including the conceptual model, research variables, data collection, and analytical strategy. Afterwards, there will be correlation analysis, common method variance test, confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modeling, and competing model analysis in the section of the empirical analysis, followed by the conclusion.

2. Theory and hypothesis

2.1. Social capital and business networks

Social capital offers actors with convenient resources, includ-ing norms, trust, and network. As indicated inColeman’s (1988)

social capital theory, an individual does not exist in the society alone but instead forms connections with other people due to various reasons; such connections are called ‘‘social networks.’’ Social capital is an import resource embedded in the relationship structure of these networks and takes advantage of the mutual trust and interpersonal interaction so as to exchange resources and information to fulfill personal goals and action. According to

Burt (1992), social capital is defined as an opportunity to use resources. The opportunity arises from relationship built in the

past. He believed more resources and benefits can be gained by making good use of interpersonal networks and seizing distribu-tion channels to obtain central posidistribu-tions and intermediary status. The definition of business networks is derived from the interaction in a social relationship network. Initially, Mitchell (1969) defined networks as relationship existing in a group of people, affairs and things. Different types give rise to different relationship networks, which consist of three elements, namely actors, relationship among actors and access connecting actors. Relationship among actors refers to the kind of interaction arising from networking. Such interaction could be a formal relationship defined by social norms or laws or an informal one due to constant interaction. Actors build relationship through either two-way or one-way connected access. The access is called ‘‘ties,’’ which can be divided into strong ties and weak ties based on the extent of strength (Granovetter, 1973).

Tichy et al. (1979) explained a specific type of connection among a group of people and then, based on the connection, explained the social behavior of the people in a network. Then,

Knoke and KuKlinski (1982) expanded the idea of a group of people to a certain type of relationship among individuals or affairs. Afterwards, more researchers (e.g., Jarillo, 1988; Larson, 1992; Thorelli, 1986) applied the concept to organizations and companies, giving rise to the idea of business networks to represent the operation of markets and hierarchical structures. Business networks can be regarded as an aggregation of organiza-tions, and are used to cater for a specific market through connected relationship taking place repeatedly within the orga-nizations. Zeng et al. (2010)found that the cooperation among different companies has the most impact on the innovation

performance of small and medium enterprises. Baum et al.

(2000)in their study on Canadian biotech start-ups found that new businesses could raise their innovation performance by lowering the expenses spent on information and technologies in an alliance network. In light of the literature, and according to the perspective of transaction costs, resource dependence view and cross-organizational learning theory, the construction and inter-action of business networks can help an individual network lower costs, diversify risks, procure key resources, enhance competi-tiveness, expand new markets, promote dynamic learning, obtain exterior knowledge, increase innovation efficiency, and even-tually shore up competitive advantages and bring gains to an enterprise.

2.2. Mediating effects of business networks

Generally, when a new organization is short on heterogeneity and valuable resources, its ties to the business networks will be comparably weaker, and it will be difficult for the organization to

construct more advantageous network relationship (Ahuja,

2000b). Therefore, the new organization tends to build relation-ship with previous working partners so that it can indirectly obtain the required resources (Gulati, 1995;Sorenson and Stuart, 2001). Many start-ups have had their own indirect ties before constructing their first network. For example, a start-up founder may have ties with a previous working partner, so the founder can use the ties to acquire the needed information, technologies, or resources to build up his own business networks.

Through the founder’s indirect ties, other prospective partners

will emerge and work with the start-ups (Hallen, 2008). The

prospective partners will then believe they can gain more advantages or benefits through the connection. Therefore, multi-ple business networks enable the start-up to have contact with other organizations in the same industry (Burt, 1992), to share resources and capabilities (Ahuja, 2000a; Gulati, 1995), to gain financial capital (Katila et al., 2008;Sorenson and Stuart, 2001), to

generate benefits from the ties with suppliers and customers (Uzzi, 1996), or to promote organizational innovation through cooperation (Baum et al., 2000; Powell et al., 1996). Besides, in terms of the perspective of transaction costs, through business network relationship, long-term, and close-knit cooperation can spare the trouble of preventing opportunism, hence lowering the transaction costs, such as searching, negotiation, contracting, supervision, and default. Meanwhile, it also reduces processing time and increases efficiency (Uzzi, 1997), which allows a busi-ness to concentrate on its core competences and to bring forth organizational innovation. Therefore, the study proposes the following hypotheses.

H1a. The ties of a start-up founder can enhance organizational innovation through business network connection.

H1b. The ties of a start-up founder can elevate organizational performance through business network connection.

Though start-ups cannot use their advantages to construct networks in the beginning, prospective partners may get to notice whether founders are capable of enhancing human capital, such as

production skill and knowledge (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven,

1996;Hsu, 2007;Shane and Stuart, 2002). For a new start-up, the professional background, previous achievements and experience of its founder would be taken into account to see whether his human capital is capable of contending with challenges ahead (Baum and Silverman, 2004;Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1990). A founder’s human capital, including various professional skills, knowledge, and successful management experience, is a key factor to attract potential partners to build up relationship. It is because most potential partners will worry whether a startup can sustain manage-ment, whether the relationship can last, and whether the founder is capable of successfully running an organization. Hence, potential partners may work with start-ups whose founder has substantial human capital (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1990; Higgins and Gulati, 2003).

In terms of the resource dependence perspective, a business can gain the required complementary resources through business networks, such as capital, human resources, market information, and technological skills, so as to enhance its competitive advantages (Moller and Halinen, 1999). Through the interaction of business networks, an organization can enjoy benefits, such as human resources exchange, expertise training, technology transfer, and critical knowledge exchange. The start-up can gain the benefits of organizational innovation as well as market information exchange (Chen and Lin, 2002). The start-up can then confirm what require-ment customers have, what product customers prefer, and what price customers can afford. In doing so, it can keep up with market trends, improve practicality of products, streamline production processes, and reinvent products in order to manufacture saleable, reasonably-priced merchandise and enhance efficacy of organiza-tional innovation. Furthermore, according to cross-organizaorganiza-tional learning, business networks also have influence on organizational learning and knowledge exchange. Since networks have an outward characteristic, they can quickly absorb new information and spread outward, expediting the innovation process within networks (Lynn et al., 1996). The interaction of business networks enables the information transfer channel to be more multi-dimensional, and allows knowledge created and absorbed to be more abundant and useful, which will be beneficial to organizational innovation. Based on the literature, the study proposes the following hypotheses. H2a. The human capital of a start-up founder can enhance organizational innovation through business network connection. H2b. The human capital of a start-up founder can elevate organiza-tional performance through business network connection.

2.3. Organizational innovation and performance

According to the resource-based perspective, organizational innovation is helpful in encountering a competitive business environment, organizational management, and establishing com-petitive advantages (Han et al., 1998; Raymond and St-Pierre, 2010). Molina-Morales and Martı´nez-Ferna´ndez (2010)believed innovational activities include product innovation and process innovation. An organization seeking to sustain competitive advantages needs to reinvent itself constantly, and develop new business models, products, and production processes. Successful organizational innovation will reward the organization with customer support, and boost organizational development as well as corporate profits. In the previous research studies, innovation was considered an effective strategy to boost organizational performance (Butler, 1988; Drucker, 1985), and an important mechanism for a business to keep itself informed of the outer

competitive environment. Moreover, Subrahmanya (2005)

defined innovation as a company applying new knowledge or key techniques to development, manufacturing, or service. Besides, according to the literature review on organizational innovation and organizational performance, there is a positive and significant correlation between the two (e.g.,Chen and Chen, 2006; Damanpour et al., 2009; Eddleston et al., 2008; Liao and Rice, 2010; Naranjo-Gil, 2009; Subrahmanya, 2005; Yam et al., 2004). Therefore, the study proposes the following hypothesis. H3. The organizational innovation of a start-up has a positive influence on organizational performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Conceptual framework

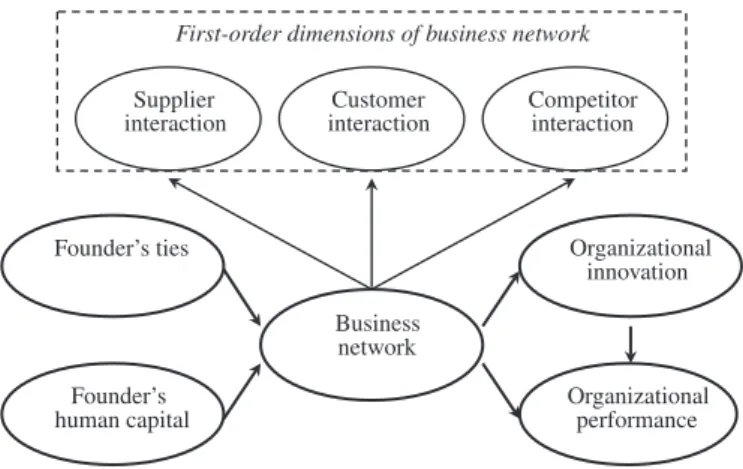

With social capital and business networks in mind, the study explores whether a founder’s ties and human capital, after mediated by business network, would have an impact on organizational innovation and performance. The focal point of the research study is the mediating effect of business network. According toGem ¨unden et al. (1996)andRing and Van de Ven (1992), in a theoretical model, business network is conceptualized as a second-order construct composed of three potential first-order dimensions: supplier inter-action, customer interinter-action, and competitor interaction. Indicated inFig. 1is the conceptual framework.

3.2. Research variables

There are seven research dimensions in the study, including a founder’s ties, a founder’s human capital, supplier interaction, customer interaction, competitor interaction, organizational inno-vation, and organizational performance. The following are opera-tional definitions of variables; the items for measurement are shown in theAppendix.

A founder’s ties refer to the connection that a founder builds with his partners through direct or indirect contact. The dimen-sion regards the number of partners, frequency, interaction, and

depth as the measurement of connection strength (BarNir and

Smith, 2002; Burt, 1992; Hallen, 2008). This study uses four question items to measure founder’s ties. In addition, founder’s ties are focused on individual-level social networks. A founder’s human capital refers to the founder’s education level (Hallen, 2008; Palmer and Barber, 2001; Westphal and Stern, 2006), professional background (Hsu, 2007), previous work experience (Beckman et al., 2007; Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1990), and successful experience (Hsu, 2007;Shane and Stuart, 2002), all of which are characteristics of expertise, wisdom, capability, and

experience. This study uses four question items to measure founder’s human capital.

Business networks are complex webs of interdependent exchange relationships among firms and organizations. From the external stakeholders’’ perspective, business networks may consist of manifold actors and complex interactions with custo-mers, suppliers, creditors (including banks and bondholders), governments, unions, universities, local communities, and the general public. While the study explores the business network, it focuses on the interactions with the upstream supplier firms, downstream firms, and competitors within the industry chain. Compared to the founder’s ties, business network is focused on business-to-business networks. In terms of the level of the net-work, a key distinction is that founder’s tie is interpersonal network, while business network concerns the relationships of inter-firms. Hence, business network comprises three interac-tions, including supplier interaction, customer interaction, and competitor interaction. Supplier interaction refers to the interac-tion with suppliers (Gem ¨unden et al., 1996). This study uses four question items to measure supplier interaction. Customer inter-action refers to the interinter-action with downstream customers (Gem ¨unden et al., 1996). This study uses four question items to measure customer interaction. Competitor interaction refers to the interaction with competitors (Gem ¨unden et al., 1996). This study uses four question items to measure competitor interaction. Organizational innovation is comprised of product innovation and process innovation. Product innovation means that a company can provide a new or differentiated product/service to meet customer requirements (Jime´nez-Jime´nez and Sanz-Valle, 2011;

Mesquita and Lazzarini, 2008). Process innovation means that a company can provide a better production or service process than the current one to help the organization reach the best perfor-mance (Jime´nez-Jime´nez and Sanz-Valle, 2011;Damanpour et al., 2009). This study uses ten question items to measure organiza-tional innovation. Organizaorganiza-tional performance refers to the exam-ination of organizational goal attainment, including average return on investment (ROI), average profit rate, average return of sale (ROS), average market share growth rate, and average sales growth rate. This study uses five question items to measure organizational performance.

3.3. Data collection and samples

The study uses the questionnaire survey as the main data collection tool. The original version of the questionnaire was translated into Chinese by the authors and then translated back from Chinese to English by two bilingual foreign language experts. Content validity refers to the degree to which elements

of a measurement instrument are relevant and the representative of the targeted construct for a particular assessment purpose (Haynes et al., 1995). In order to achieve the content validity of the research instrument, all of the instruments are assessed by nine specialists in the field of strategic management, innovation management, and organization management. In addition, the study conducts field interviews with 10 founders, asking them a series of open-ended questions regarding the role of the founders and organization innovation in an emerging market. After the face-to-face interviews with those founders, the study then conducts the survey. In the pre-test stage, the study chooses 35 founders of China-based Taiwanese small and medium enter-prises to conduct the questionnaire survey. The pre-test results show each dimension of Cronbach’s

a

is above 0.8, and all of the questions are applicable for the subsequent research and analysis. In the formal survey stage, the study samples from China-based Taiwanese small and medium enterprises, and the questionnaire survey has two phases. During the first phase, surveys and introduction letters attached to mails and email are sent to participants. Three weeks later, reminders and surveys are sent to those who have yet to respond. The study also uses the telephone survey as a complementary tool to boost response rates (Dilman, 1978). Since the research subject is China-based Taiwanese small and medium enterprises, the distribution and collection of the questionnaire surveys would be difficult. For the convenience of sampling, the researcher uses his personal net-work relationship and collects 230 copies of surveys. Excluding the incomplete surveys, the valid surveys come to 222 copies. When confirming the representativeness of the research samples, the study conducts the evaluation of the effects of non-response. Therefore, through the comparison between the first batch of collected data (participants who respond earlier) and the second batch of collected data (participants who respond later), the biasof non-respondents can be evaluated (Armstrong and Overton,

1977). According toArmstrong and Overton (1977), t-test is used to examine the characteristics of earlier respondents and later respondents. For example, in terms of organizational scales and annual sales at the 5% of significant levels, there is no significant difference between the earlier respondents and later ones.

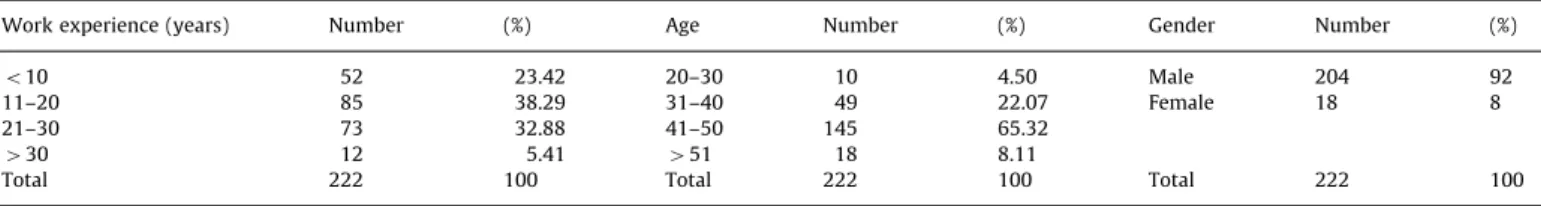

Table 1 is the statistics of the sample. As indicated in the research sample, 92% of the participants are male and 8% of the participants are female. Majority of the respondents (about 92%) are males and this result is not surprising in China-based Taiwanese small and medium enterprises of male-dominated founders. Generally, most Taiwanese entrepreneurs leaving for China are male and females are in the minority. Besides, there are some couples leaving for China together, but the majority of founders are still male. This is the reason why female founder account for only 8% of the respondents. In terms of founders’ work experience, the item of 11–20 years accounts for the most percentage. As for the age of the founders, the item of 41–50 years old accounts for the most percentage. The study collected the questionnaire surveys in 2010, and the collection took approximately two months.

3.4. Analytical strategy

Firstly, the study uses confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the quality and adequacy of the measurement model. CFA is used to test whether measures of a construct are consistent with the nature of that construct. CFA is also frequently used as a first step to assess the proposed measurement model in a structural equation model. Specifically, the study treats the business net-work as a second-order construct with three first-order construct components. Accordingly, second-order factor analysis is con-ducted for testing the construct validity.

First-order dimensions of business network

Business network Organizational innovation Organizational performance Competitor interaction Customer interaction Supplier interaction Founder’s ties Founder’s human capital

Then, to clarify the relationship among these variables, struc-tural equation modeling (SEM) is used to examine the hypothe-sized model’s fit and the hypotheses. The structural equation model comprises two parts, the measurement model and the structural equation model. The measurement model indicates how latent variables or hypothetical constructs depend upon or are indicated by the observed variables. The model describes the measurement properties (reliabilities and validities) of the observed variables. Meanwhile, the structural equation model specifies the causal relationships among the latent variables, describes the causal effects, and assigns the explained and unexplained variance (J ¨oreskog and S ¨orbom, 1996).

Finally, this study uses the recommendations of Bentler and Bonett (1980)and uses the nested models comparison for further analysis of mediating effects. The nested model is a simpler model derived from a more complex model; that is, the model comes from another limited model. In other words, when free para-meters are limited in a certain model, a containment relationship appears between the two models. This is called the ‘‘nested relationship’’, and the model required to meet this relationship is called the ‘‘nested model’’. Using the nested model not only verifies the goodness of fit of the model, but also helps compare different models and discover their goodness of fit. Nested model analysis is based on the chi-square difference test, which com-pares the goodness of fit of the model to the data to test the framework of this study and the appropriateness of the logical derivation. This study focuses on business network and explores whether there is a mediating effect and influence between the founders’ own resources and start-up outcomes (innovation and performance).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The study firstly illustrates the results of the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis and then conducts the analysis of structural equation modeling (SEM). Indicated in

Table 2 are the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis of each research variable.

4.2. Common method variance test

Common method variance (CMV) is a potential problem for behavioral research (Podsakoff et al., 2003), which could occur when a single participant responds either to all the variables or to all the items within a single survey (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). As a precaution, the study has adopted measures, such as hiding the information of the participants, hiding the meanings of the items, randomizing the order of the items, devising the items in a reverse order and organizing the wording of the items to prevent the occurrence of common method variance. Besides, the study also adoptsHarman’s (1967)single factor analysis to conduct posterior

examination of the common method variance (Podsakoff and

Organ, 1986). After conducting the initial factor analysis of the evaluation items, the study generates 10 factors, accounting for 76.3% of the accumulative explanation, of which factor 1 accounts for 15.3% of the variance. Since the single factor analysis does not yield much of a difference, the problem of common method variance in the study is not very serious.

4.3. Confirmatory factor analysis

The study uses confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the convergent validity of each construct.Table 3indicates that the t-test values of each construct’s evaluation items are above the significant level (t-values greater than 1.96). The factor loadings (

l

) of all the observatory variables versus latent variables are between 0.65 and 0.82. These values climb above the thresh-old, 0.45, proposed byBentler and Wu (1993), which indicates that all of the observatory variables can reflect their constructs and that the scale of the study has a certain extent of convergent validity. In terms of the composite validity of the construct, the composite reliability of the seven constructs is between 0.82 and 0.86, which also meets the requirement of 0.6 and suggests that the constructs have validity. In terms of average variance extracted, the values of the seven constructs are all above 0.5,Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis (N ¼ 222).

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

1. Founder’s ties (0.89)

2. Founder’s human capital 0.388nn

(0.90) 3. Supplier interaction 0.430nn 0.308nn (0.88) 4. Customer interaction 0.134nn 0.167nn 0.306nn (0.91) 5. Competitor interaction 0.346nn 0.332nn 0.431nn 0.438nn (0.89) 6. Organizational innovation 0.261nn 0.376nn 0.487nn 0.407nn 0.527nn (0.90) 7. Organizational performance 0.303nn 0.316nn 0.251nn 0.246nn 0.411nn 0.476nn (0.92) Mean 5.545 5.672 5.870 5.834 5.860 5.670 5.985 S.D. 0.570 0.534 0.592 0.567 0.584 0.589 0.540

Figures in parentheses are Cronbach’s alphas. nn

po0.01. Table 1

Characteristics of the sample.

Work experience (years) Number (%) Age Number (%) Gender Number (%)

o10 52 23.42 20–30 10 4.50 Male 204 92

11–20 85 38.29 31–40 49 22.07 Female 18 8

21–30 73 32.88 41–50 145 65.32

430 12 5.41 451 18 8.11

Han, J.K., Kim, N., Srivastava, R.K., 1998. Market orientation and organizational performance: is innovation a missing link? Journal of Marketing 62 (4), 30–45.

Harman, H.H., 1967. Modern Factor Analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Haynes, S.N., Richard, D.C.S., Kubany, E.S., 1995. Content validity in psychological

assessment: a functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological Assessment 7, 238–247.

Higgins, M.C., Gulati, R., 2003. Getting off to a good start: the effects of upper echelon affiliations on underwriter prestige. Organization Science 14 (3), 244–263.

Hsu, D., 2007. Experienced entrepreneurial founders, organizational capital and venture capital funding. Research Policy 36 (5), 722–741.

Huang, H.C., 2011. Technological innovation capability creation potential of open innovation: a cross-level analysis in the biotechnology industry. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 23 (1), 49–63.

Huang, Y.A., Chung, H.J., Lin, C., 2009. R&D sourcing strategies: determinants and consequences. Technovation 29 (3), 155–169.

Jap, S.D., Ganesan, S., 2000. Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commit-ment. Journal of Marketing Research 37 (2), 227–246.

Jarillo, J.C., 1988. On strategic networks. Strategic Management Journal 9 (1), 31–41. Jime´nez-Jime´nez, D., Sanz-Valle, R., 2011. Innovation, organizational learning, and

performance. Journal of Business Research 64 (4), 408–417.

J ¨oreskog, K., S ¨orbom, D., 1996. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Scientific Software International, Chicago. Kaasa, A., 2009. Effects of different dimensions of social capital on innovative activity:

evidence from Europe at the regional level. Technovation 29 (3), 218–233. Kajikawa, Y., Takeda, Y., Sakata, I., Matsushima, K., 2010. Multiscale analysis of

interfirm networks in regional clusters. Technovation 30 (3), 168–180. Katila, R., Rosenberger, J.D., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2008. Swimming with sharks:

technology ventures, defense mechanisms and corporate relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly 53 (2), 295–332.

Knoke, D., KuKlinski, J.H., 1982. Network Analysis: Basic Concepts. Sage, Beverly Hills. Koch, C., 2004. Innovation networking between stability and political dynamics.

Technovation 24 (9), 729–739.

Larson, A., 1992. Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: a study of the govern-ance of exchange relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly 37 (1), 76–104. Li, Y., Vanhaverbeke, W., 2009. The effects of inter-industry and country difference in supplier relationships on pioneering innovations. Technovation 29 (12), 843–858. Liao, T.S., Rice, J., 2010. Innovation investments, market engagement and financial performance: a study among Australian manufacturing SMEs. Research Policy. 39 (1), 117–125.

Lin, J.L., Fang, S.C., Fang, S.R., Tsai, F.S., 2009. Network embeddedness and technology transfer performance in R&D consortia in Taiwan. Technovation 29 (11), 763–774.

Lin, J., Si, S.X., 2010. Can guanxi be a problem? Contexts, ties, and some unfavorable consequences of social capital in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 27 (3), 561–581.

Lynn, L.H., Reddy, N.M., Aram, J.D., 1996. Linking technology and institutions: the innovation community framework. Research Policy 25 (1), 91–106. Marsh, H.W., Hocevar, D., 1985. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the

study of self-concept. Psychological Bulletin 97, 562–582.

Marsh, H.W., Hocevar, D., 1988. A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses. Journal of Applied Psychology 73, 107–117. Martin, J.A., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2010. Rewiring: cross-business-unit collaborations

in multibusiness organizations. Academy of Management Journal 53 (2), 265–301.

McEvily, B., Zaheer, A., 1999. Bridging ties: a source of firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities. Strategic Management Journal 20 (12), 1133–1156. Mention, A.L., 2011. Co-operation and co-opetition as open innovation practices in

the service sector: which influence on innovation novelty? Technovation 31 (1), 44–53.

Mesquita, L.F., Lazzarini, S.G., 2008. Horizontal and vertical relationships in developing economies: implications for SMEs’ access to global markets. Academy of Management Journal 51 (2), 359–380.

Mitchell, J.C., 1969. Social Networks in Urban Situations: Analyses of Personal Relationships in Central African towns. Manchester, Published for the Institute for Social Research, University of Zambia, by Manchester U.P.

Molina-Morales, F.X., Martı´nez-Ferna´ndez, M.T., 2010. Social networks: effects of social capital on firm innovation. Journal of Small Business Management 48 (2), 258–279.

Moller, K., Halinen, A., 1999. Business relationships and networks: managerial challenge of network era. Industrial Marketing Management 28 (5), 413–427. Morgan, R.E., Berthon, P., 2008. Market orientation, generative learning, innova-tion strategy and business performance inter-relainnova-tionships in bioscience firms. Journal of Management Studies 45 (8), 1329–1353.

Nahapiet, J., Ghoshal, S., 1998. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organiza-tional advantage. Academy of Management Review 23 (2), 242–266. Naranjo-Gil, D., 2009. The influence of environmental and organizational factors

on innovation adoptions: consequences for performance in public sector organizations. Technovation 29 (12), 810–818.

Palmer, D., Barber, B.N., 2001. Challengers, elites and owning families: a social class theory of corporate acquisitions in the 1960s. Administrative Science Quarterly 46 (1), 87–120.

Pfeffer, J., Salancik, G.R., 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

Podolny, J.M., 1994. Market uncertainty and the social character of economic exchange. Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (3), 458–483.

Podsakoff, P.M., Organ, D.W., 1986. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. Journal of Management 12 (4), 531–544.

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P., 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recom-mended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5), 879–903.

Powell, W.W., Koput, K.W., Smith-Doerr, L., 1996. Interorganizational collabora-tion and the locus of innovacollabora-tion: networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (1), 116–145.

Raymond, L., St-Pierre, J., 2010. R&D as a determinant of innovation in manufac-turing SMEs: an attempt at empirical clarification. Technovation 30 (1), 48–56. Ring, P.S., Van de Ven, A.H., 1992. Structuring co-operative relationships between

organizations. Strategic Management Journal 13 (7), 483–498.

Santos, F.M., Eisenhardt, K.M., 2009. Constructing niches and shaping boundaries: a model of entrepreneurial action in nascent markets. Academy of Manage-ment Journal 52 (4), 643–671.

Shane, S., Stuart, T.E., 2002. Organizational endowments and the performance of university start-ups. Management Science 48 (1), 154–170.

Sorenson, O., Stuart, T.E., 2001. Syndication networks and the spatial distribution of venture capital investments. American Journal of Sociology 106 (6), 1546–1588. Subrahmanya, M.H.B., 2005. Pattern of technological innovations in small

enter-prises: a comparative perspective of Bangalore (India) and Northeast England (UK). Technovation 25 (3), 269–280.

Tichy, N.M., Tushman, M.L., Fombrun, C., 1979. Social network analysis for organizations. Academy of Management Review 4 (4), 507–519.

Tippins, M.J., Sohi, R.S., 2003. IT competency and firm performance: is organiza-tional learning a missing link. Strategic Management Journal 24 (8), 745–761. Thorelli, H.B., 1986. Networks: between markets and hierarchies. Strategic

Management Journal 7 (1), 37–51.

Tolstoy, D., Agndal, H., 2010. Network resource combinations in the international venturing of small biotech firms. Technovation 30 (1), 24–36.

Uzzi, B., 1996. The sources and consequences of embededness for the economic performance of organizations: the network effect. American Sociological Review 61, 674–698.

Uzzi, B., 1997. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: the paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly 42 (1), 35–67.

Venkatraman, N., 1989. The concept of fit in strategy research: toward verbal and statistical correspondence. Academy of Management Review 14, 423–444. Venkatraman, N., 1990. Performance implications of strategic coalignment: a

methodological perspective. Journal of Management Studies 27, 19–41. Walker, G., Kogut, B., Shan, W., 1997. Social capital, structural holes and the

formation of an industry network. Organization Science 8 (2), 109–125. Westphal, J.D., Stern, I., 2006. The other pathway to the boardroom: interpersonal

influence behavior as a substitute for elite credentials and majority status in obtaining board appointments. Administrative Science Quarterly 51 (2), 169–204. Yam, R.C.M., Guan, J.C., Pun, K.F., Tang, E.P.Y., 2004. An audit of technological innovation capabilities in Chinese firms: some empirical findings in Beijing, China. Research Policy 33 (8), 1123–1140.

Zeng, S.X., Xie, X.M., Tam, C.M., 2010. Relationship between cooperation networks and innovation performance of SMEs. Technovation 30 (3), 181–194.

Hao-Chen Huang is currently an Assistant Professor of the Graduate Institute of Finance, Economics, and Business Decision, National Kaoh-siung University of Applied Sciences in Taiwan. He received his Ph.D. degree in organization and strategy from Graduate Institute of Business Administration, National Taiwan University. His research areas include strategic management, innovation management, performance manage-ment, and organizational behavior.

Mei-Chi Lai is currently a Ph.D. Candidate of the Graduate Institute of Health Care Organization Administration, National Taiwan University in Taiwan. Her research areas include health care organization manage-ment, performance managemanage-ment, and strategic management.

Kuo-Wei Lo is a Master of the Graduate Institute of Commerce, National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences in Taiwan. His research areas include health care organization management, strategic management, and innovation management.