Determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients

treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues for

chronic hepatitis B

Short title: Determinants of HBV-HCC under NUCYao-Chun Hsu1,2, Chun-Ying Wu1,3,4, Hsien-Yuan Lane1, Chi-Yang Chang2, Chi-Ming

Tai2, Cheng-Hao Tseng2, Gin-Ho Lo2, Daw-Shyong Perng2, Jaw-Town Lin5*,

Lein-Ray Mo2*

1Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung,

Taiwan

2Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine,

E-Da Hospital/I-Shou University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

3School of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

4Division of Gastroenterology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung,

Taiwan

5 School of Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei, Taiwan

Correspondence to Lein-Ray Mo, MD; Department of Internal Medicine, E-Da Hospital/I-Shou University, 1, E-Da Rd., Kaohsiung 824, Taiwan;

Tel: +886-7-6150011 ext. 2978; Fax: +886-7-6150940; email: moleinray@gmail.com

* Jaw-Town Lin and Lein-Ray Mo supervised and contributed equally to this work.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus; liver cirrhosis; antiviral therapy; diabetes mellitus; risk

stratification 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

Word Counts: 249 in the abstract; 1999 in the main text SYNOPSIS

Objectives: We aimed to identify determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in

cirrhotic patients who received nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Patients and methods: This retrospective-prospective study screened all patients

(N=1,630) who received antiviral therapy for CHB between 1 September, 2007 and 31 March, 2013 at the E-Da Hospital, and enrolled 210 consecutive cirrhotic patients with pretreatment viral DNA >2,000 IU/mL. Those who developed HCC within 3 months of treatment were excluded. All participants were observed until occurrence of HCC, death, or 1 January 2014. The incidence and determinants of HCC were estimated using competing risk analyses adjusted for mortality.

Results: Thirty-five (16.7%) patients developed HCC during a median follow-up of

25.2 months (interquartile range, 16.3-37.3 months), with a cumulative incidence of 24.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.3-32.0%) at 5 years. Multivariate–adjusted analyses identified age >55 years (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.19; 95% CI, 1.03-4.66), male gender (adjusted HR, 3.07; 95% CI, 1.05-9.02), MELD score >12 points (adjusted HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.10-4.23), and diabetes mellitus (DM; adjusted HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.54-7.91) as independent risk factors after adjusting for multiple covariates including anti-diabetes medication. A scoring formula that used information of age, gender, MELD score, DM, and anti-diabetes regimen significantly 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45

discriminated patients at high or low risk of HCC, with sensitivity and specificity of 82.9% and 62.3%, respectively.

Conclusions: Age, gender, hepatic dysfunction, DM, and medication for DM are

baseline factors that stratify the risk of HCC in cirrhotic patients who receive nucleos(t)ide analogues for CHB.

46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the leading etiology of liver-related morbidity and mortality, globally accounting for more than 50% of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs).1, 2 Transcriptional and translational activity of the virus drives

hepatocellular carcinogenesis in the natural history of chronic hepatitis B (CHB).3, 4

Through inhibition of the viral polymerase, antiviral therapy using nucleos(t)ide analogue (NUC) potently suppresses HBV replication.5 It can effectively ameliorate

hepatitis, attenuate liver fibrosis, and delay disease progression.6 Even overt cirrhosis

may regress after long-term NUC therapy.7, 8 Furthermore, a growing body of data has

indicated that NUC treatment is associated with reduced occurrence and recurrence of HBV-related HCC.9, 10

Antiviral therapy may decrease but nevertheless does not eliminate the risk of HCC.11 Some patients, especially those with existing cirrhosis, still develop HCC

despite taking NUCs. The outcome determinants have not been elucidated in patients under antiviral treatment, and risk stratification in treated patients cannot rely on knowledge learned from untreated cohorts. This study aimed to investigate the chronological pattern and pretreatment risk factors of HCC in a CHB cohort with cirrhosis under continuous NUC therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

Study design and patient population

This was a retrospective-prospective cohort study conducted in a teaching hospital in Taiwan (E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan). The institutional review board of the hospital approved this study (protocol identification: EMRP-102-010). Through a computerized database, we first identified all CHB patients who received NUC between 1 September, 2007 and 31 March, 2013, and then manually reviewed their medical records to determine eligibility. The inclusion criteria were a positive serology of HBsAg or a documented history of HBV infection for 6 months or more, antiviral treatment with NUCs, presence of cirrhosis, and serum HBV DNA greater than 2,000 IU/mL. Cirrhosis was either histopathologically or clinically diagnosed. Clinical diagnosis was based principally on the sonographic evaluation of liver surface, parenchyma, vascular structure, and splenomegaly.12 In the absence of

histological proof, reimbursement of NUCs for the indication of CHB-related cirrhosis required presence of splenomegay or esophagogastric varices in addition to sonographic diagnosis.9 Those who met any of the following criteria were excluded:

superimposed infection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus, any malignant disease, organ transplantation, prior exposure to NUC or interferon, and occurrence of HCC within 3 months of therapy.

Antiviral treatment with NUC and surveillance for HCC 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99

Enrolled patients received lamivudine 100 mg, entecavir 0.5 mg, telbivudine 600 mg, or tenofovir 300 mg once daily. Adefovir was not used in the first line but restricted in the rescue setting, per the regulation of the Taiwan National Health Insurance. For those who acquired on-treatment virological breakthrough, adefovir at a daily dose of 10mg was added. Occasionally, dosage might vary according to individual conditions such as renal impairment. All patients were followed up at an interval no longer than 3 months. All received HCC surveillance by means of ultrasonography and serum alpha-fetoprotein every 3 months in general.13 HCC was

diagnosed according to international guidelines.2 Non-invasive diagnosis must fulfil

characteristic features on dynamic images. Patients were observed from the initiation of NUC therapy until occurrence of HCC, death, loss to follow-up, or 1 January, 2014.

Assessment of clinical parameters and laboratory measurement

We manually reviewed and recorded clinical and laboratory data from the computerized database, including the behaviour of alcohol consumption with regard to the duration of drinking, types of beverage, and average amount per day. In principle, alcoholism was defined if the consumption exceeded 40g in men and 20g in women on a daily basis for 5 years.14 Accuracy of the collected information was

audited by the principle investigator (YCH), who also ascertained the outcome of 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118

each enrolled subject. Serology of HBV was assayed by immunoassays (ABBOTT GmbH& Co., Wiesbaden, Germany). The serum level of HBsAg was semi-quantified with the upper bound of 250 IU/mL, per the manufacturer’s protocol. Viral DNA was measured by the branched DNA assay (VERSANT® 440 Molecular System., Siemens

Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA) before 1 May, 2010, and afterward by the real-time PCR method (Roche COBAS® TaqMan® 48; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The detection range was 357 to 17,857,100 IU/mL for the former assay and 6 to 110,000,000 IU/mL for the latter. Viral load was logarithmically transformed for expression, and values above the measurable range were recorded at one log above the upper bound. Virological breakthrough was defined if HBV DNA resurged to more than 10-fold from nadir; signature mutations for resistance were then sought. The Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD) score,15 the Aspartate aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI),16 and the Risk

Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B (REACH-B) score were computed according to the original formulas.17

Data Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed with the median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables with proportions. Death occurring prior to HCC was considered as a competing risk event. The modified Kaplan-Meier method and the 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137

Gray's method were used to calculate the cumulative incidence of HCC.18 Independent

factors associated with HCC were analyzed by the modified Cox proportional hazard model that was adjusted for competing risks and multiple covariates.19 The hazard

ratio (HR) along with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported. Data was managed and analyzed by the commercially available software (Stata, version 9.1; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). The competing risk analyses were performed using the R software with the “cmprsk_2.1-4” package. A p value <0.05 defined statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

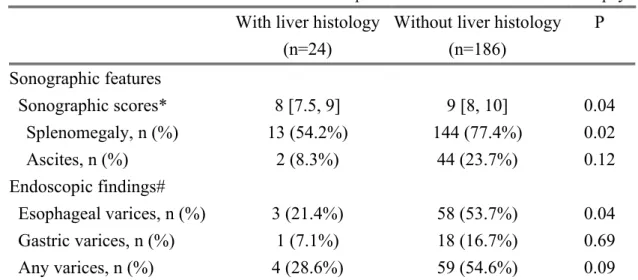

After screening a total of 1,630 consecutive patients (Figure 1), we finally enrolled 210 patients into analysis (Table 1). Thirty of the 49 diabetic patients had been using metformin. Drug resistance was detected in 2 patients taking entecavir (1.1% among all entecavir users). Cirrhosis was clinically diagnosed in most patients whereas histological proof was available in 24 participants (11.4%). Those who were clinically diagnosed appeared to be more severe on ultrasonography and endoscopy ( Table 2). HCC occurrence under continuous NUC therapy

Thirty five (16.7%) patients developed HCC during a median follow-up of 25.2 months (IQR, 16.3-37.3 months), with a cumulative incidence of 24.1% (95% CI, 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157

16.3-32.0%) at 5 years (Figure 2). The vast majority of HCCs (n=34) occurred within 3 years of therapy.

Among 102 patients who had viral DNA data after one year, 86 patients (84.3%) found virus undetectable in serum. Except for 2 patients who were later confirmed to have drug resistance, all of the patients with detectable HBV DNA had viral load lower than 300 IU/mL (median 34 IU/mL, range 7- 248 IU/mL).

Univariate and multivariate-adjusted factors predictive of HCC under NUC In the univariate Cox regression analyses (Table 3), age, gender, diabetes mellitus (DM), ascites, MELD and REACH-B scores were associated with HCC. In the multivariate-adjusted analysis including adjustment for anti-diabetes drugs in diabetic patients, older age, male gender, higher MELD score, and DM were independent risk factors.

Age >55 years, male gender, MELD score >12 points, and DM significantly discriminate the risk of HCC (Figure 3). Interestingly, the incidence of HCC was significantly lower in diabetic patients who took metformin than those who used other drugs (Supplementary Figure 1).

Risk score to predict the occurrence of HCC

These uncovered risk factors were weighted according to their regression coefficients in the Cox model (Table 4). The simplified calculation using integers was as accurate as that based on the original formula in predicting HCC (Figure 4A). 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177

Information of anti-diabetes medication significantly improved performance of the predictive model (Supplementary Figure 2). A risk score of 5 points or more significantly discriminate patients at high risk of HCC (Figure 4B), with sensitivity and specificity of 82.9% and 62.3%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that despite potent antiviral treatment, HCC still occurred frequently in cirrhotic patients with highly viremic CHB. Age, gender, hepatic dysfunction, and DM were independent risk factors unraveled in the multivariate-adjusted analysis. In addition, information of anti-diabetes medication was associated with improvement of risk stratification in diabetic patients. Our findings not only demonstrate that HCC surveillance remains essential in CHB patients under antiviral treatment, but also uncover those who require particular attention. Furthermore, this research underscores the unmet need for therapies beyond viral suppression to further attenuate risks in patients with advanced CHB.

Characterized by liver cirrhosis, male predominance, advanced age, and high serum level of HBV DNA, this cohort consists of patients at extremely high risk of

HCC.20, 21 Although emerging data indicates that cirrhosis may regress in NUC users,

apparently it takes time, usually requiring 5 years or more.7, 8 Importantly, we did not

find markers of viral activity, i.e. concentration of viral DNA or serology of HBeAg, 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197

could stratify the risk, in contrast to previous studies of untreated CHB. Therefore, our findings exemplify the importance of different models for distinct scenarios. In view of the widespread use of NUCs for CHB, there is an urgent need for more knowledge to better understand the risk stratification in patients under treatment. Of note, our study focused on pretreatment factors that determined later development of HCC, but did not address their dynamic changes. Some parameters such as alpha-fetoprotein may change during treatment in association with occurrence of HCC.22, 23

Because age and hepatic dysfunction indicate chronicity and severity of accumulated hepatic damage, our data suggest that hepatocarcinogenesis in long-standing HBV infection cannot be sufficiently abolished by viral inhibition, at least not within 3 years of therapy. Longer observation is warranted to further elucidate the pattern and predictors of HCC occurring alongside the NUC treatment. Besides, the sexual dimorphism in HCC probably results from mechanisms beyond viral carcinogenesis,24, 25 and therefore it may require a targeted therapy to attenuate the risk

conferred by male gender.

A number of studies have shown the association between DM and HCC,26, 27

although the exact mechanism is incompletely understood.28 Moreover, a recent

research reported that diabetic patients were less likely to have cirrhosis regress after NUC therapy.8 Our data further indicate that DM is becoming a major outcome

198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216

determinant of CHB in the era of antiviral therapy. We also found an inverse association between metformin use and HCC risk, in line with existent literature.29, 30

Because metformin is a first-line agent that diabetic patients usually start with, its use may identify those with early or mild DM and therefore result in the association. Whether there is anti-tumor efficacy associated with metformin is certainly interesting,31 but beyond the scope of the present research. Regardless, our data

supports that information of anti-diabetes medication is valuable for assessing the risk of HCC in diabetic patients.

Our study has the following strengths. First, stringent criteria for clinical diagnosis ascertained the presence of cirrhosis and enabled application of our findings to a clear patient group. Second, insomuch as virological data after one-year treatment attested potent viral inhibition, therapeutic efficacy was unlikely to confound the analysis. Furthermore, the competing risk analysis has accounted for influence of mortality on estimating the incidence of HCC.32 Finally, all patients were followed up

at an interval shorter than 3 months, allowing timely detection of HCC.

The following limitations are noted. First, it requires external validation to extrapolate our conclusion to patients without cirrhosis. Second, we were unable to explore some potentially important factors including HBV genotype, familial predisposition, exposure to aflatoxin, and co-infection with hepatitis D virus (HDV). 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235

Incorporation of family history into analysis could introduce recall bias, especially when most participants were older than 50 years. Checkup of HDV is regrettably not a routine practice receiving reimbursement in Taiwan where the prevalence is low.33, 34

Nevertheless, previous landmark studies from Asia did not find HDV was a significant determinant of HCC.17, 20, 21 Finally, this single-center study from a referral

hospital could not rule out the possibility of selection bias.

In summary, cirrhotic patients with HBV viremia still have a high risk of HCC despite treatment with NUCs, at least in the first 3 years of therapy. A clinically convenient model based on routinely available parameters that comprise age>55 years, male gender, MELD score>12 points, DM and medication for DM can stratify the risk.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Hsiu J. Ho, Ms. Jing-Ju Lee and Ms. Ya-Li Tseng for their assistance. Preliminary results were presented at the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW) 2013 (OP234 in the session of viral hepatitis B), on 15 October, 2013, in Berlin, Germany.

FUNDING: This study was supported by research grants from the E-Da Hospital

(EDAHP-101009) and the Tomorrow Medical Foundation (Grant No.102-3). 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255

TRANSPARENCY DECLARATIONS

Yao-Chun Hsu reports having received lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Harvester Trading Co. (the authorized distributor of tenofovir in Taiwan). Jaw-Town Lin reports having received research support in another study from the Gilead Sciences. There are no other conflicts of interest to declare. All other authors had nothing to declare.

256 257 258 259 260 261 262

REFERENCES

1. El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1264-1273 e1.

2. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2.

3. Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65-73.

4. Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, et al. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low HBV load. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1140-1149 e3; quiz e13-4.

5. Osborn MK, Lok AS. Antiviral options for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;57:1030-4.

6. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521-31. 7. Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the

reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;52:886-93.

8. Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282

follow-up study. Lancet 2013;381:468-75.

9. Wu CY, Chen YJ, Ho HJ, et al. Association between nucleoside analogues and risk of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following liver resection. JAMA 2012;308:1906-14.

10. Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 2013;58:98-107.

11. Sherman M. Does hepatitis B treatment reduce the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma? Hepatology 2013;58:18-20.

12. Hung CH, Lu SN, Wang JH, et al. Correlation between ultrasonographic and pathologic diagnoses of hepatitis B and C virus-related cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:153-7.

13. Poon D, Anderson BO, Chen LT, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: consensus statement from the Asian Oncology Summit 2009. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1111-8.

14. Lin CW, Lin CC, Mo LR, et al. Heavy alcohol consumption increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2013;58:730-5.

15. Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302

Hepatology 2000;31:864-71.

16. Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2003;38:518-26.

17. Yang HI, Yuen MF, Chan HL, et al. Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B (REACH-B): development and validation of a predictive score. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:568-74.

18. Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann. Stat 1988. 16:1141-1154.

19. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. JASA1999; 94:496-509.

20. Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2009;50:80-8.

21. Wong VW, Chan SL, Mo F, et al. Clinical scoring system to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1660-5.

22. Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Nishimura T, et al. alpha-fetoprotein levels after interferon therapy and risk of hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2013;58:1253-62. 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322

23. Wong GL, Chan HL, Tse YK, et al. On-treatment alpha-fetoprotein is a specific tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving entecavir. Hepatology 2013 (Epub ahead of print).

24. Li Z, Tuteja G, Schug J, et al. Foxa1 and Foxa2 are essential for sexual dimorphism in liver cancer. Cell 2012;148:72-83.

25. Ma WL, Hsu CL, Wu MH, et al. Androgen receptor is a new potential therapeutic target for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2008;135:947-55, 955 e1-5.

26. El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:369-80.

27. Chen CL, Yang HI, Yang WS, et al. Metabolic factors and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by chronic hepatitis B/C infection: a follow-up study in Taiwan. Gastroenterology 2008;135:111-21.

28. Siddique A, Kowdley KV. Insulin resistance and other metabolic risk factors in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2011;15:281-96, vii-x.

29. Singh S, Singh PP, Singh AG, et al. Anti-diabetic medications and the risk of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:881-91; quiz 892. 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342

30. Chen HP, Shieh JJ, Chang CC, et al. Metformin decreases hepatocellular carcinoma risk in a dose-dependent manner: population-based and in vitro studies. Gut 2013;62:606-15.

31. Pernicova I, Korbonits M. Metformin-mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014.

32. Hsu YC, Ho HJ, Wu MS, et al. Postoperative peg-interferon plus ribavirin is associated with reduced recurrence of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013;58:150-7.

33. Huo TI, Wu JC, Lin RY, et al. Decreasing hepatitis D virus infection in Taiwan: an analysis of contributory factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997;12:747-51.

34. Pascarella S, Negro F. Hepatitis D virus: an update. Liver Int 2011;31:7-21. 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

Characteristics All (n = 210) No HCC (n = 175) HCC (n = 35) P

Age, years 52.8 [46.0, 60.3] 52.0 [45.1, 59.9] 57.1 [50.8, 62.0] 0.01 Male gender, n (%) 154 (73.3%) 123 (70.3%) 31 (88.6%) 0.04 Body mass index, kg/m2 25.6 [23.0, 28.2] 25.7 [23.0, 28.2] 24.0 [23.0, 26.4] 0.15

HBeAg positive, n (%) 46 (21.9%) 38 [21.7%] 8 [22.9%] 0.83 HBV DNA, log IU/ml 5.52 [4.22, 6.40] 5.44 [4.26, 6.31] 5.85 [4.21, 6.77] 0.49 HBsAg >100 IU/ml, n (%) 190 (90.5%) 159 (90.9%) 31 (88.6%) 0.75 AST, IU/L 66 [47, 98] 60 [43, 92] 86 [65, 127] 0.0003 ALT, IU/L 54 [42, 87] 53 [41, 83] 64 [48, 112] 0.07 Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/ml 7.77 [4.86, 15.84] 7.2 [4.7, 13.1] 14.3 [7.5, 26.6] 0.003 Bilirubin, mg/dL 1.26 [0.92, 1.77] 1.25 [0.91, 1.74] 1.38 [0.98, 2.34] 0.73 INR 1.12 [1.04, 1.22] 1.12 [1.03, 1.19] 1.16 [1.09, 1.28] 0.03 Creatinine, mg/dL 1.1 [1.0, 1.2] 1.1 [0.9, 1.2] 1.2 [1, 1.3] 0.004 Platelet, 103/µL 110 [75, 144] 111 [76, 145] 106 [68, 137] 0.7 Hemoglobin, g/dL 13.2 [11.3, 14.7] 13. 5[11.7, 14.7] 12.3 [10.9, 14.7] 0.23 Leucocyte, /µL 5230 [4260, 6810] 5230 [4260, 6630] 5200 [4290, 6820] 0.79 Diabetes mellitus, n (%) 49 (23.3%) 36 (20.6%) 13 (37.1%) 0.05 Hypertension, n (%) 31 (14.8%) 23 (13.1%) 8 (22.9%) 0.19 Dyslipidemia, n (%) 14 (6.7%) 13 (7.4%) 1 (2.9%) 0.47 Alcoholism, n (%) 28 (13.3%) 23 (13.1%) 5 (14.3%) 0.79 Splenomegaly, n (%) 157 (74.8%) 135 (77.1%) 22 (62.9%) 0.09 Ascites, n (%) 46 (21.9%] 35 (20.0%) 11 (31.4%) 0.18 Varices*, n/N (%) 63/122 (51.6%) 50/100 (50.0%) 13/22 (59.1%) 0.49 MELD score 10.17 [7.38, 12.38] 9.98 [7.33, 11.91] 11.46 [8.70, 14.97] 0.007 APRI 1.94 [1.03, 2.94] 1.70 [0.99, 2.86] 2.36 [1.60, 4.93] 0.01 REACH-B 11.5 [10,13] 11 [10, 13] 13 [11, 14] 0.005 Antiviral agent 0.04 Entecavir, n (%) 169 (80.5%) 137 (78.3%) 32 (91.4%) Tenofovir, n (%) 25 (11.9%) 25 (14.3%) 0 Telbivudine, n (%) 11 (5.2%) 9 (5.1%) 2 (5.7%) Lamivudine, n (%) 5 (2.4%) 4 (2.3%) 1 (2.9%)

Data are expressed as median [interquartile range) or number (percentage). *Only 122 patients had upper endoscopy at baseline; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B s antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; REACH-B, risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis 355 356 357 358 359 360

B.

Table 2. Clinical evaluation of liver cirrhosis in patients with and without liver biopsy

With liver histology (n=24)

Without liver histology (n=186) P Sonographic features Sonographic scores* 8 [7.5, 9] 9 [8, 10] 0.04 Splenomegaly, n (%) 13 (54.2%) 144 (77.4%) 0.02 Ascites, n (%) 2 (8.3%) 44 (23.7%) 0.12 Endoscopic findings# Esophageal varices, n (%) 3 (21.4%) 58 (53.7%) 0.04 Gastric varices, n (%) 1 (7.1%) 18 (16.7%) 0.69 Any varices, n (%) 4 (28.6%) 59 (54.6%) 0.09

Notes. *The sonographic scores comprised evaluation of liver surface, parenchyma, vascular structure, and splenomegaly, with a minimum of 4 and maximum of 11 points. # Endoscopy was performed in 122 patients at baseline.

361 362

363 364 365

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for the risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma

Univariate analysis Multivariate analysis

Variable Crude HR 95 % CI P Adjusted HR 95% CI P

Age, per year 1.04 1.01~1.07 0.01

Age >55 years 2.16 1.09~4.29 0.03 2.19 1.03-4.66 0.04

Male gender 3.05 1.08~8.64 0.04 3.07 1.05-9.02 0.04

Body mass index, kg/m2 0.92 0.84~1.01 0.07 HBsAg >100 IU/ml 0.54 0.19~1.55 0.25

HBeAg positive 1.28 0.58~2.82 0.55

HBV DNA, per log IU/ml 1.06 0.85~1.31 0.63

AST, per 10U/L 1.0 0.99~1.01 0.90

ALT, per 10U/L 1.0 0.98~1.01 0.76

Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/ml 1.0 1.0~1.0 0.95 Bilirubin, per mg/dL 1.0 0.90~1.10 0.93

INR, per unit 2.26 0.72~7.10 0.16

Creatinine, per mg/dL 1.14 0.93~1.41 0.20 Platelet, per 103 cells/µL 1.0 0.99~1.01 0.73 Hemoglobin, per g/Dl 0.92 0.80~1.05 0.21 Leucocyte, per 103 cells/µL 1.06 0.94~1.20 0.32

Diabetes mellitus* 2.13 1.07~4.23 0.03 3.49 1.54-7.91 0.003 Hypertension 1.63 0.74~3.60 0.22 Dyslipidemia 0.34 0.05~2.50 0.29 Alcoholism 1.16 0.45~3.00 0.76 Splenomegaly 0.63 0.32~1.25 0.19 Ascites 2.11 1.03~4.32 0.04

MELD score, per point 1.06 1.01~1.12 0.02

MELD >12 points 2.69 1.38~5.23 0.004 2.16 1.10-4.23 0.03

APRI, per point 1.01 0.95~1.06 0.83

REACH-B, per point 1.23 1.04~1.45 0.02 Antiviral therapy

Entecavir 1

Tenofovir ※

Telbivudine 1.18 0.28~4.99 0.82

Lamivudine 1.33 0.18~9.73 0.78

*adjusted for use of metformin in the multivariate analysis, ※ not calculable due to no HCC in tenofovir users; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HBeAg, 366

367

368 369

hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; REACH-B, risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B.

Table 4. β coefficient in the Cox proportional hazard model and the corresponding risk scores to predict development of hepatocellular carcinoma

β coefficient 95% CI Score 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394

Age > 55 years 0.78 0.08~1.48 2 Gender Male 1.11 0.05~2.17 3 MELD score > 12 points 0.76 0.07~1.45 2 Diabetes mellitus

Diabetics using metformin -0.55 -1.76~0.66 0

Diabetics without metformin 1.31 0.53~2.10 3

FIGURE LEGENDS:

Figure 1: Flow chart of the enrollment process. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411

Figure 2: Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients under nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B.

Figure 3: Incidence of hepatocelluar carcinoma stratified by risk factors at baseline. (A) stratified by age > or ≦55 years; (B) stratified by gendr; (C) stratified by

MELD score > or ≦12 points; (D) stratified by DM; DM, diabetes mellitus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Figure 4: Performance of the risk scores based on the baseline risk factors. (A)

the receiver operating characteristic curves of the predictive formula to predict HCC; (B) a risk score of 5 points or more identifies patients at high risk of HCC. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423