The marketisation of higher education in Hong Kong

since 2000

趙致洋

倫敦大學亞非學院碩士

Master‟s graduate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Introduction

Globalisation has been an overwhelming process in recent decades. It is, arguably, a process (or set of processes) which embodies a transformation in the spatial organization of social relations and transactions – assessed in terms of their extensity, intensity, velocity and impact – generating transcontinental or interregional flows and networks of activity, interaction, and the exercise of power (Held, McGrew, Goldblatt and Perraton, 2003, p.68). As Giddens (2002) once suggests, we are now living in “runaway world” that is beyond the control of individual nation-states. As one country “liberalizes” their economy, others have to deregulate the business sector so as to increase competitiveness to conform to the “race to the bottom” agenda in neo-liberal globalization. It encourages the withdrawal of the government in social policy and the participation of the private sector, which is supposed, albeit arguable, to allocate and employ resources more efficiently. Hence, marketisation and privatisation, which will be explored in more detail later on, has transformed different aspects of the public sector. The state is restructured as a result of the sweeping

effect of globalization (Ferlie, Ashburner, Fitzgerald and Pettigrew, 1996, Flynn, 2007, Osbourne and Gaebler, 1993).

Higher education system is thus inevitably influenced by the wave of marketisation and privatization all across the world. In this essay, transformation of the higher education system by marketisation in Hong Kong will be studied. The year 2000 is considered as the turning point because the Chief Executive Tung Chee-Hwa (2000) encouraged the set-up of tertiary institutions by the private sector in his fourth policy address. This paper will argue that higher education in Hong Kong has been largely, if not wholly, marketised since 2000. I will first discuss the idea of traditional higher education and the definition of marketisation and privatization in social policy and higher education. Then, the features and impact of adopting neo-liberal measures in higher education will be critically discussed. By illustrating the case of Hong Kong, the paper attempts to show that marketisation is situated in the wider global context with similar characteristics.

The aims and objectives of

higher education

Higher education in general refers to the education that is given after the secondary education, whereas universities are the main provider. The original word of “Universitas” in Latin means the “whole, total, universe, world”. Universities were established in the middle ages that taught universal knowledge. Developed in the 12th and 13th century where the state and the church were the most powerful institutions, university was also a place for further training on profession like law, theology and medicine. In other words, it was a place for providing the apparatus necessary for “the pursuit of learning” (Oakeshott, 2004). Thus, as a relatively autonomous sector, universities are always supposed to devote to free speech, critical thinking and the search for new knowledge. Academics including students could express their minds and ideas without constraint from the state, and thus provide alternative views to the one of the authorities.

However, as Scott argued (1995), mass higher education systems developed since the 1990 has become more heterogeneous in sociological terms and heterodox in intellectual sense due to divergent culture and social diversity in a post-industrial world. Even so, the education ideal of the university which emphasizes moral integration and intellectual synthesis has not been easily abandoned (Scott, 1995).

In short, as argued by Barnett (1990), in spite of its plurality, higher education continues to play a distinctive role in the society, with a dual aim to emancipate its students through a process of critical reflection and advancing knowledge. The institutionalization of these values, according to Barnett (1990), has made the university as a key instrument in maintaining an open society.

What is marketisation and

privatization?

Marketisation and privatization could be regarded as an important process under the neo-liberal agenda of globalization. Although the two concepts are conceptually different, in practice, they often go in the same direction. A market could be referred as “a system of social coordination whereby the supply and demand for goods or services is balanced through the price mechanism” (Brown, 2009, p.1). Marketisation upholds the neo-liberal ideology that the market is the most efficient and effective mechanism in allocating resources through fair competition. The market could also provide more choices for consumers, more flexibility to respond to needs and, most of all, better quality of services through open flow of information, effective use of resources and keener competition (Djelic, 2006; Peters, 2002). In terms of the role of the state, marketisation encourages the

restructuring and retreat of the state in the provision of public goods and invites private enterprises to manage the non-market institutions such as education and social services (Dale, 1997; Offe, 1990). In other words, the government should deregulate and privatise the public sector as much as possible so that the market could maximize its effects. Thus, marketisation and privatization often go hand in hand in social policy (Chitty, 1997; Ramanadham, 1988). Thus, it could also be regarded as the “mcdonaldization” of society that emphasizes efficiency, quantification and calculability (Mok, 1999; Ritzer, 2008). Nevertheless, in the contemporary neo-liberal globalization, the perfectly free market does not really exist in the realm of social policy because the state is still playing a regulatory role in operation. Thus, what is actually operating nowadays could be called a quasi-market.

Marketisation and Privatisation in Higher education

Discussing marketisation and privatization particularly in the realm of education, Brown (2011) suggests that there are four main indicators to recognize marketisation in higher education. They are, namely, institutional autonomy, institutional competition, price and information. Institutional autonomy refers to the

freedom of higher education institutions to determine their own mission, programmes, fees, admissions, awards, and to a considerable extent, student and staff numbers. Brown (2011) contends that this is the freedom to specify the educational product and the process. By institutional competition, it refers to the amount of competition between institutions for students, income as well as institutional status, and these three elements are interrelated. Competition can be promoted between public institutions as well as between public and private institutions. Price is also an important indicator of marketisation in higher education. According to Brown (2011), it refers to freedom to decide on fees and the degree to which fees are controlled or regulated. As far as information is concerned, the issue is whether students have access to information that assists them in making their choice of programmes and institutions. The underlying assumption is that quality of goods is automatically protected as consumers make use of the available information to select the product that is most suitable for them. For example, institutions are compared by a set of quantified indicators and being ranked by regular „league tables‟. While this information is freely available to students, they will automatically make appropriate choices to protect their own interests.

Judged by the four indicators suggested by Brown (2011), marketisation and privatization in higher education could be manifested in two interrelated dimensions. Firstly, in terms of education policy, it introduces measures that encourage competition, introduces management skills employed in the business sector and changes financing mode from government funding to self-financing (Furedi, 2011). Secondly, in terms education objectives, it represents a retreat from the traditional values of what it means to be education. Hence, it signifies a process of turning students from being learners to consumers of “having” a degree, and higher education institutions from being ones which aim at transforming persons to confirming career opportunities and generating future income. In this process, universities increasingly emphasize the participation of businesses in funding and facilities. Hence marketisation fundamentally changes the core value of higher education as well as the mission of higher educational institutions (Molesworth, Nixon and Scullion, 2009). In short, as Slaughter and Leslie (1997) suggest, universities are eventually turned into corporations where their structure and functions are becoming more alike and provide education that served the economic purposes.

Marketisation and privatization

of higher education: The Case of

Hong Kong

The current education system in Hong Kong

The education system in Hong Kong consists of three major tiers, namely kindergarten, primary and secondary education, and post-secondary education.

Kindergarten is the first tier in the education system of Hong Kong, which is provided for children from 3 to 6 years old. Currently, all kindergartens are privately run.

The second tier of the Hong Kong education system is the primary and secondary education. Currently the Hong Kong government offers 12 years free and universal education for children and young people in Hong Kong, in which 6 years are for primary education and another 6 years are for secondary education. Before the end of Secondary six, students have to sit for the Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (DSE) in order to obtain eligibility for university entrance, or entrance to other private higher education institutes.

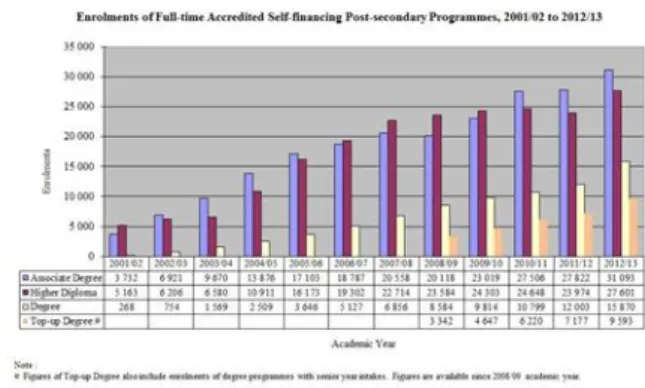

The third tier of the education system in Hong Kong is post-secondary education. At present, there are eight government funded degree awarding universities or higher education institute in Hong Kong1, which together offer a total of 15,000 first-year first degree places for secondary school leavers each year. Apart from government funded higher education institutions, there are at present 25 higher education institutes offering self-financed degree, top-up degree as well as sub-degree places for eligible students. The private sector of post-secondary education has witnessed a great expansion in the last decade. In 2001, only 268 school leavers enrolled in self-financed undergraduate degree programmes, but the number has increased to 25,463 in 2012 (including 9,593 top-up degree places), representing an increase of 94 times over 12 years (See table 1). In addition to the great expansion of self-financed undergraduate degree places, there is also a remarkable expansion in the self-financed sub-degree sector. In 2001, only 8,895 students enrolled in full-time self-financed sub-degree programmes, but this has increased to 58,694, representing an increased on 5.6 times (See table 1). Details of massive expansion and marketisation will be critically discussed in the following sections.

Table 1 : Enrolments of Full-time Accredited Self-financing Post-secondary programmes, 2001/02 to 2012-13

Source: Information Portal for Accredited Post-secondary Programmes, Hong Kong SAR Government, http://www.ipass.gov.hk/edb/index.php/en/home/ statheader/stat/stat_el_index

Prelude to the significant marketisation in 2000: massification from late 1980s to mid-1990s

Although the year of 2000 could be considered as the turning point in the development of higher education in Hong Kong, it was not the starting point of marketisation. Market measures were introduced to higher education institutions since the massification from late 1980s to mid-1990s. Before the 1970s, there were only two universities in Hong Kong, namely The University of Hong Kong and The Chinese University of Hong Kong that provided higher education. The admission rate of students among the age-appropriate group was only 2% and thus higher education was virtually elitist in nature (Wan, 2011). Although there were other private postsecondary education institutions, the two universities were the only government-funded and degree-granting institutions in Hong Kong. On the other hand, higher

education was also considered as highly instrumental and functional to provide human resources that were required by the bureaucracy and the economic development. Thus, though higher education was predominantly elitist, the value and objective was by no means similar to those in the ideal of higher education. It serves the economic demand of the development of Hong Kong.

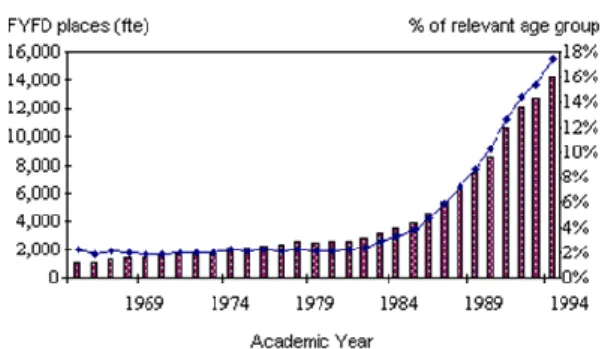

In the late 1980s, the government decided to increase the number of students entering higher education drastically (Education Commission, 1988). By that time, the participation rate of age-appropriate group had already rose from 2% in the 1970s to 8% in late 1980s (University and Polytechnic Grant Committee, 1993; University Grant Committee, 1996), yet the government proposed that the rate should rise to not less than 18% by the year of 1994-95 (Policy Address, 1989) (See Table 2). This goal of expansion in higher education is met by upgrading four local colleges and polytechnics to offer degree programmes (Education Commission, 1992). Thus, higher education in Hong Kong has turned away from elitism and experienced its first massification, where the supply of undergraduate places was doubled in six-year‟ time (Cheng, 1996; Mok, 2001). Nevertheless, the main motivation for the government to change its education policy was still

economically-driven. As the economy of Hong Kong was transformed from labour-intensive to service and knowledge economy in late 1980s, there was higher demand for labour with higher education in both the public and private sector. Students in higher education were necessary to support the sustainable development of the Hong Kong economy (Education Commission, 1990). Hence, the existence of higher education in Hong Kong is not for educating and learning itself, but for producing human resources that are required by labour market demands.

Table 2: Undergraduate participation rate in Hong Kong, 1964-1994

Source: University and Polytechnic Grant Commission Committee Interim Report (1993)

As a result of mass higher education, there were comments concerning the decline of quality of higher education and the loss of competitiveness of the students compared to other places in Asia (Mok, 2001). In response to these concerns, the University Grant Committee (UGC) required the universities to enhance global competition for the first time in the interim report in 1993 (Chan, 2011). More importantly in the light of

marketisation, quality assurance reviews and assessment exercises such as Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), Teaching and Learning Quality Process Review (TLQPR) and Management Review (MR) were introduced. These measures thus started to transform the higher education sector towards the market direction. RAE forced the academics to fulfil the requirements for funding through the quantity of articles that are published in internationally peer-reviewed journals. The contributions and performance of academics are thus judged by the quantified indicators rather than the quality of research. TLQPR emphasizes the aspect of teaching and learning processes, placing the obligation and accountability for assuring and enhancing quality of teaching and learning as the highest agenda. Nonetheless, it shifts the education process to external scrutiny which is not based on educational values and objectives but market values. MR also introduces the management styles of the business sector and emphasizes „value-for-money‟. It gives the UGC the authority to intervene in the formerly internal affairs of the managerial systems of the individual higher education institutions to ensure their efficient and effective use of resources. In short, these quality assurance measures have started off the marketisation process of higher education by quantifying the

performance of higher education institutions and academics that could be measured by indicators.

Substantial marketisation since 2000

As mentioned above, the year of 2000 could be considered as the turning point of the development of higher education in Hong Kong, as it experienced another even more drastic expansion in the participation of students to postsecondary institutions. Since the handover of the sovereignty from Britain to China in 1997, the SAR government of Hong Kong has put its policy emphasis on education. In particular, the Chief Executive announced and promised in the Policy Address of 2000 that 60% of age-appropriate youth would receive postsecondary education by the end of that decade to meet the needs of a knowledge-based economy (Tung, 2000). Again, it could be seen that higher education is serving the demands of the economic development and upgrading the students to face the global competition as a result of globalization (Education Commission, 2000; Mok, 2001). It was once commented as a “big leap forward” as the participation rate in higher education was only 18% by the end of the 1990s. Yet, unlike the massification in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the government did not participate more in the provision and funding of higher

education, but to achieve the goals through privatization and marketisation measures.

1. Privatisation of higher education

As Tung made it explicit in his Policy Address (2000), the government “will facilitate tertiary institutions, private enterprises and other organisations to provide options other than the traditional sixth form education, such as professional diploma courses and sub-degree courses” (Paragraph 67). To meet the massive expansion of the participation rate of higher education, the government introduced the Associate Degree (AD) programme focusing on transmitting general knowledge to students, which resembles the community college in USA (Chan, 2011; Wan, 2011). This kind of degree is inferior to the bachelor degree but shorter and cheaper. Yet, the government did not fund them but encouraged the existing UGC-funded universities to offer self-financed AD courses. On the other hand, the government also invited the involvement of private institutions in providing more courses for students. Thus, it started the process of privatization of higher education, and the role of the government is transformed from the sole funder to a regulator (Mok, 2001). The government aimed at creating the competition for students between the self-financed courses provided by the UGC-funded

universities and those by private institutions. It intended to allow the market mechanism to decide the numbers of student admitted and the level of tuition fee of each institution. Nonetheless, this has not resulted as perfect as the government intended. The university affiliated institutions were in a much more advantageous and competitive position in attracting students than the private institutions in terms of prestige, reputation and resources. As a result, in the name of fair competition, the government urged the total separation between the self-financed programmes and their affiliated universities and banned cross-subsidy between them (UGC, 2002). Yet, in spite of being financially independent, university-affiliated self-financed sectors could still enjoy better prestige and reputation to attract more students. In short, the massification of higher education since 2000 represented the beginning of privatization by inviting private organizations to provide postsecondary education. In the private market, students are nothing more than customers who pay the tuition fees for a qualification. Private institutions are also competing for students like in any other markets competing for customers. Both the price (tuition fees) and the quantity (numbers of students) are decided by the demand and supply in the market. To satisfy the demands of the customers, academics are pressurized to suit their

taste and sacrifice education needs. Thus in this angle, higher education of the private institutions is highly marketised.

2. Deepening marketisation in the publicly-funded higher education

Apart from the privatization of higher education since 2000, the government-funded higher education has also experienced the deepening of marketisation, which had started in the 1990s through adopting the quantified indicators of the market.

Firstly, role differentiation between the eight UGC-funded universities was introduced (UGC, 2004). The universities were requested to develop excellence in their unique role based on its strengths. Admittedly, role differentiation and developing quality education is not necessarily a measure of marketisation. However, the role-related performance accounts for about 10% of the funding of UGC to universities (UGC, 2005). It is said that it is used to “provide an assurance that the institutions are following their chosen roles and that they perform well in those roles” (UGC, 2005, Paragraph 15). Yet, it in fact introduces competition between institutions for the funding and sanctioned them when they are not up to “standard”.

Besides, the UGC also marketised the funding system which allows competitive bidding. Constituting 22%

of the university subsidy by the government, research grants are marketised when the UGC introduced the strategy of top-slicing by designating a certain percentage to be re-allocated by market competition (UGC, 2010). Moreover, similar measures were proposed by the UGC in terms of student quota to increase the incentive for competition. Traditionally, student quota of the universities was set by the UGC according to their different roles, and the number of students of each university account for 66% of the funding from UGC each year. The strategy of top-slicing was again used in 2010 to “liberalize” the student quota, in which 5% of the first-year-first-degree intakes by a particular UGC-funded university are re-allocated by competition (UGC, 2010). In the same report, the UGC (2010) also promised that competition will increasingly become the major mode of funding. By creating an internal market within the higher education sector that allows competition for funding and number of students, it is believed that public accountability, efficiency and effectiveness of the use of resources are achieved in the governance of universities under the ethos of neoliberalism and public sector management (Chan, 2007; Chan, 2011; Chan and Lo, 2007; Hood, 1995; Mok, 1999, 2001), where quality of teaching and research is believed to be achieved through competition of limited resources

(UGC, 2010). However, this process creates and perpetuates internal inequality of resources between institutions, where the „haves‟ tend to gain more, and the „have-nots‟ further suffer from inferiority in terms of prestige and resources.

In addition, marketisation has also created inequality between academics within and between universities. This is attributed to the delinking of staff salary packages between the UGC-funded higher education institutions and those in the civil service. As a result, the wage rates and benefit package of academics are determined according to the market based on quantifiable demand and supply, and academics have to demonstrate their „value-for-money‟ by means of quantified outputs. This change is supported by the rationale that it gives more freedom and flexibility to the management of higher education institutions. Nevertheless, at the same time, universities have to depend on the support of private sector funding to sustain their growth and to perform their assigned role in Hong Kong so as to receive the funding of the government. As a result, they have to accommodate the interests of the businesses so as to attract their funds. It further added pressure to the higher education institutes to reform themselves in neo-liberal terms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this essay has critically evaluated the extent of marketisation of higher education in the case of Hong Kong, in particular after the year of 2000. It is argued that higher education is marketised to a very large extent. Not only are involvement of privatized institutions introduced, education nowadays emphasizes quality and excellence in terms of measurable indicators, accountability to external scrutiny and efficient and effective use of resources through market competition. Higher education in Hong Kong has departed from the traditional aims and objectives of higher education. Although participation in higher education is widened, the relationship between students and academics is transformed to service provider and customer (Furedi, 2011).

In the future, it could be foreseen that the higher education would march towards the direction of more competition to maximize the economic efficiency. It effectively differentiates those students who are able and willing to pay higher tuition fees from others. However, it should be noted that Hong Kong is not the only experience that higher education is marketised and the problem is situated in the wider context globally. Under the influence of neo-liberal globalization, the pressure of marketisation in higher education is across other parts of Asia and the world (Chan and Mok, 2001; Lynch, 2006; Mok, 2003; 2007; Mok and Lo, 2002; Tan, 1998).

Bibliography

Barnett, R. (1990). The idea of higher education. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

Brown, R. (2009). The role of the market in higher education, Higher Education Policy Institute, Available from:

http://www.hepi.ac.uk/2009/03/18/the-ro le-of-the-market-in-higher-education/ (accessed on 26/5/2014).

Brown, R. (2011). The march of the market. In M. Molesworth, R. Scullion & E. Nixon (Eds.), The marketisation of higher education and student as

consumer (pp. 11-24). Oxon: Routledge. Chan, D. K. K. (2007). Global agenda, local responses: changing education governance in Hong Kong‟s higher education. Globalization,

Societies and Education, 5 (1), 109-124. Chan, D. K. K. & Lo, W. (2007). Running universities as enterprises: university governance changes in Hong Kong. Asian Pacific Journal of

Education, 27 (3), 305-322. Chan, D. & Mok, K. (2001). Educational reforms and coping strategies under the tidal wave of marketisation: a comparative study of Hong Kong and the Mainland.

Comparative Education, 37 (1), 21-41.

Chan, Y. M. (2011). Higher

education policy in the midst of change: role transformation of the government in Hong Kong. Bristol: University of Bristol.

Cheng, K. (1996). Markets in a socialist system: reform of higher education. In K. Watson, S. Modgil, & C. Modgil (Eds.), Educational

dilemmas: debate and diversity, vol. 2: reforms in higher education (pp. 238-249). London: Cassell.

Chitty, C. (1997). Privatization and marketization. Oxford Review of

Education, 23 (1), 45-62.

Dale, R. (1997). The state and the governance of education: an analysis of the restructuring of the state-education relationship. In A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown & A. S. Wells (Eds.),

Education: Culture, Economy and Society (pp. 273-282). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Djelic, M. (2006). Marketisation: from intellectual agenda to global policy-making. Transnational

governance, Institutional dynamics of regulation, 53-73.

Education Commission (1988). Education Commission Report, No.3. Hong Kong: Education commission.

Education Commission (1990). Education Commission Report, No.4. Hong Kong: Education commission.

Education Commission (1992). Education Commission Report, No.5. Hong Kong: Education commission.

Education Commission (2000). Learning for life; learning through life: reforms proposals for the education system in Hong Kong. Hong Kong SAR: Education Commission.

Ferlie, E., Ashburner, L.,

Fitzgerald, L. & Pettigrew, A. (1996). The new public management in action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flynn, N. (2007). Public sector management. London: SAGE Publications.

Furedi, F. (2011). Introduction to the marketisation of higher education and the student as consumer. In M. Molesworth, R. Scullion & E. Nixon (Eds.), The marketisation of higher education and student as consumer (pp. 1-8). Oxon: Routledge.

Giddens, A. (2002). Runaway world: how globalisation is reshaping our lives. London: Profile Books. Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D. & Perraton, J. (2003). Rethinking Globalization. In D. Held & A. McGrew

(Eds.), The global transformations reader: an introduction to the globalization debate (pp. 67-74). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hood, C. (1995). The “new public management” in the 1980s: variation on a theme. Accounting, Organization and Society, 20 (2/3), 99-109.

Information Portal for Accredited Post-Secondary Programmes (2013). Enrolments of full-time accredited self-financing post-secondary

programmes. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printers. Available from: http://www.ipass.gov.hk/edb/index.php/e n/home/statheader/stat/stat_el_index (accessed on 19/5/2014).

Lynch, K. (2006). Neo-liberalism and marketisation: the implications for higher education. European Educational Research Journal, 5 (1), 1-17.

Mok, K. H. (1999). The cost of managerialism: the implications for the „McDonaldisation‟ of higher education in Hong Kong. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 21 (1), 117-127.

Mok, K. (2001). Academic

capitalization in the new millennium: the marketisation ad corporatization of higher education in Hong Kong. Policy and Politics, 29 (3), 299-315.

Mok, K. (2003). Globalisation and higher education restructuring in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China. Higher Education Research & Development, 22 (2), 117-129.

Mok, K. H. (2007). The search for new governance: corporatisation and privatisation for public universities in Malaysia and Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 27 (3), 271-290. Mok, J. K. H. & Lo, E. H. C. (2002). Marketisation and the changing governance in higher education: a comparative study. Higher Education and Management and Policy, 14 (1), 51-82.

Molesworth, M., Nixon, E. & Scullion, R. (2009). Having, being and higher education: the marketisation of the university and the transformation of the student into consumer. Teaching in Higher Education, 14 (3), 277-287. Oakeshott, M. (2004). The idea of a university. Academic Questions, 17 (1), 23-30.

Offe, C. (1990). Reflection on the institutional self-transformation of movement politics: a tentative stage model. In R. J. Dalton & M. Koehler (Eds.), Challenging the political order: new social and political movements in western democracies (pp. 232-250). New York: Oxford University Press.

Osbourne, D. & Gaebler, T. (1993). Reinventing government: how the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. New York: Penguin. Peters, B. G. (2002). The changing nature of public administration: from easy answers to hard questions. Asian Journal of Public Administration, 24 (2), 153-183.

Ramanadham, V. V. (1988). The concept and rationale of privatization, In V. V. Ramanadham (Ed.), Privatisation in the UK (pp. 3-25). London:

Routledge.

Ritzer, G. (2008). The

McDonaldization of society 5. London: Pine Forge Press.

Scott, P. (1995). The meanings of mass higher education. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Slaughter, A. & Leslie, L. L. (1997). Academic capitalism: politics, policies and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tan, J. (1998). The marketisation of education in Singapore: policies and implications. International Review of Education, 44 (1), 47-63.

Tung, C. W. (2000). The 2000 Policy Address: serving the community; sharing common goals. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer.

University and Polytechnic Grants Committee (1993). Higher education 1991-2001 - an interim report. Hong Kong: University and Polytechnic Grants Committee.

University Grants Committee (1996). Higher education in Hong Kong: report of the University Grants Committee. Hong Kong: University Grants Committee.

University Grants Committee (2002). Higher education in Hong Kong: report of the University Grants Committee. Hong Kong: University Grants Committee.

University Grants Committee (2004). Hong Kong higher education: to make a difference, to move with the times. Hong Kong: University Grants Committee.

University Grants Committee (2005). A note on the funding

mechanism of UGC: formula, criteria and principles for allocating funds

within UGC-funded institutions. Hong Kong: University Grants Committee.

University Grants Committee (2010). Aspirations for the Higher Education System in Hong Kong: Report of the University Grants Committee. Hong Kong: University Grants Committee.

Wan, C. (2011). Reforming higher education in Hong Kong towards post-massification: the first decade and challenges ahead. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33 (2), 115-129.

Wilson, D. (1989). 1989-90 Policy Address. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer.

附註

1. Government funded universities include: City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Baptist

University, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Lingnan University, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong University of Science of Technology, and the University of Hong Kong.