Emerging Markets Finance & Trade / January–February 2012, Vol. 48, Supplement 1, pp. 192–212. Copyright © 2012 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved.

1540-496X/2012 $9.50 + 0.00. DOI 10.2753/REE1540-496X4801S112

The Impact of Bankers on the Board on Corporate

Dividend Policy: Evidence from an Emerging

Market

Yee-Chy Tseng, Ching-Ping Chang, Ruey-Dang Chang, and

Hao-Yun Liao

ABSTRACT: This study collects data from Taiwan publicly traded corporations that have banker directors between 2003 and 2007, together with a matching sample consisting of firms without banker directors. Variables used to construct empirical analyses are from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database. The results indicate that there is a nega-tive relationship between the presence of banker directors and the likelihood of dividend payment. This study contributes to lacuna in the existing banking literature by providing evidence on how banks influence listed corporate dividend policy in emerging markets. KEY WORDS: banker, board of directors, dividend policy.

Corporate governance has received increasing attention from the business press and community, with a strong emphasis on board monitoring and board independence. The causes and consequences of different corporate governance systems in place all over the world have been the subject of extensive scrutiny in recent years (Gugler 2003).

In Germany and Japan, banks take a more active role in managing financial distress. Further, banks can hold equity stakes in nonfinancial firms, making creditor rights in these

countries relatively strong (Kroszner and Strahan 2001).1 In the United States,

regula-tions restrict the range of financial services that banks can offer and prohibit banks from taking equity stakes in nonfinancial firms (Kroszner and Rajan 1997). Banks can take equity as part of a debt restructuring or bankruptcy workout plan, but they are required to sell their holdings after a specified number of years. In contrast to those countries, although banks in Taiwan can own equity stakes in nonfinancial firms, families widely control firms (Claessens et al. 2002) and are represented on the board of directors. The percentage of firms with bankers on the board in Taiwan is much lower than in Germany, Japan, and the United States, and the bank–commerce affiliation is relatively weaker. Given the relatively scarce bank capital and loose governance in the Taiwan stock market, whether banks can curtail the possibly self-serving behavior of families in such a market is questionable (Lin et al. 2009).

An important financial decision that firms’ managers face is the amount and stability of dividends. Miller and Modigliani (1961) argued that dividends are irrelevant in a world with perfect capital markets. Subsequent research discussed the issue of dividends. The finance literature contains several explanations for paying dividends, for example, the

Yee-Chy Tseng (yctseng@cc.kuas.edu.tw) is an associate professor at National Kaohsiung Uni-versity of Applied Sciences, Taiwan. Ching-Ping Chang (140198@mail.tku.edu.tw) is an assistant professor at Tamkang University, Taiwan. Ruey-Dang Chang (corresponding author; rchang@ dragon.nchu.edu.tw) is a professor in the Department of Accounting at National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan. Hao-Yun Liao (robin@takming.edu.tw) is a Ph.D. candidate at National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan.

bird-in-the-hand explanation, the tax-preference theory, and the agency theory.2, Among these, agency theory is one of the dominant explanations. Prior studies have investigated the association between dividends and corporate characteristics. For example, Jensen et al. (1992) claimed that insider ownership, debt, and dividend policy might relate directly through agency and signaling theories. Gugler (2003) found that target dividend levels, smoothing dividends, and the reluctance to cut dividends depend on the identity of the controlling owner. However, most research focuses on ownership related to dividends. Empirical evidence concerning the link between board-appointed bankers and dividends is limited. Accordingly, this study attempts to complement these findings with bankers on the board.

In East Asia, company ownership is concentrated in the hands of families. Families take an active part in management, with marked separation of control and cash-flow rights. This corporate governance system is a poorly functioning one because of the weak legal protection of small shareholders (La Porta et al. 1999). Therefore, Taiwan presents us with unique opportunities to investigate the role of bank directors in a family-dominated business environment. That is, studying how banks influence listed companies’ behav-iors through joining the board in the context of an emerging market should extend our understanding of the role of banks for corporate governance in such a market. This study analyzes the role of bankers on the board in relation to firms’ financial decisions within the context of the debt models of Byrd and Mizruchi (2005) and Kroszner and Strahan (2001), to understand the role of banker directors in this situation. This investigation conducts further research to continue this line of work, testing the influence of bankers on the board upon firms’ dividend policy, as suggested by Byrd and Mizruchi (2005). That is, when banks have some capacity to influence managerial decisions and actions, they can reduce the likelihood of expropriation by family owners. If bankers on the board

lead to lower dividends, they can mitigate the principal–principal problem.3 The

empiri-cal results of the study indicate that companies that have banker directors or a greater percentage of banker directors tend not to pay dividends. In addition, as the percentage of banker directors increases, firms pay fewer dividends.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Bankers on the Board

The effects of bankers on the board on corporate policies have been the focus of several theoretical and empirical works in recent years. Firms may gain several benefits by hav-ing bankers on their board. For example, bankers on the board may provide management expertise, especially in the form of financial or investment advice (Lorsch and Maclver 1989; Mace 1971). In addition, board-appointed bankers may enhance access to capital by economizing the cost of monitoring (Fama 1985), which in turn may lower the cost of funds (James 1987). Board positions also provide monitoring superiors for loan agree-ments due to greater information access and the ability to discipline the management through compensation or termination (Kroszner and Strahan 2001). The information advantage afforded by board positions permits better assessment of a firm’s creditwor-thiness to facilitate loans from the represented bank (Fama 1985; Kroszner and Strahan 2001). Finally, bankers on the board may be a form of certification, helping a firm secure capital from other bankers, public debt markets, or investors (Byrd and Mizruchi 2005; Fama 1985).

Some studies have considered that having bankers on the board may lead to conflicts of interest (Kroszner and Strahan 2001). Unlike other outside directors, a banker on the board of a firm has a conflict of interest between the fiduciary duty to a firm’s owners and

to the bank employer, if the bank is lending to the firm.4 The different payoff structures

associated with debt and equity lead to divergent interests in how each prefers running the firm (Dewatripont and Tirole 1994; Jensen and Meckling 1976). More specifically, shareholders generally prefer higher-risk projects than do lenders because shareholders can capture the upside benefits of risky ventures but are shielded from large losses. This conflict is most intense in firms with very risky investment opportunities and in firms

falling into financial distress (Kroszner and Strahan 2001).5

Several studies have examined the effect of bank relationships on corporate deci-sions as well as value. For example, Hoshi et al. (1991) focused on Japanese firms that

are members of a keiretsu.6 They argued that this close bank relationship can mitigate

information problems that typically arise when debt and equity are diffusely held, and no individual investor has an incentive to monitor the firm. In the case of the United States, Booth and Deli (1999) found evidence that nonlending bankers are associated with higher levels of bank debt, while no significant relationship exists between lending bankers and debt levels. They inferred from these results that nonlending bankers serve on the board as expertise providers, while the role of lending bankers is not clear. Byrd and Mizruchi (2005) suggested two possible explanations for results regarding lending bankers on the board. The first one is that lending bankers may be disabled monitors. The second possibility for the results stems from the limitations of a cross-sectional analysis. Therefore, they examined the three possible role scenarios for bankers on the board: expertise provider, enabled monitor, and disabled monitor. The results suggest that nonlending bankers provide expertise and certification for distressed firms while exercising a monitoring role for nondistressed firms.

Using data from the Spanish market, Gonzalez (2006) suggested that banks make

equity investments for both reasons.7 As banks have incentives to replace equity for debt

if agency costs with shareholders increase, the market views bank equity investment concurrent with reductions in bank debt triggered by an increase in these costs. Similarly, because banks only have incentives to lend additional debt to firms if they have positive information about their future prospects, the market infers that bank equity investment concurrent with increases in bank debt are sparked by the banks having insider informa-tion on a firm’s prospects.

Lin et al. (2009) used detailed information on bank ownership and board composition of Chinese listed companies to understand a bank’s decision to own shares of listed com-panies and the resulting implications for firm performance. They found that comcom-panies with banks as leading shareholders witness relatively poor operating performance. Their further analyses indicated that inefficient investment, resulting from bank ownership, are responsible for the disappointing performance. Lai et al. (2008) investigated the motiva-tions and effects of banks to hold equity and participate on the board of their borrowers in Taiwan. Their empirical results reveal that banks are more likely to enter the board of the businesses with higher profitability, higher proportions of tangible assets, and higher public debt ratio in the whole sample for large firms. The results are consistent with the lenders’ conflict of interest hypothesis. They also found that in the subsample of small firms, banks tend to be on a smaller board with a higher proportion of liabilities from financial institutions, supporting the agency cost hypothesis.

Overall, banks play an important role in finance by determining the availability and cost of credit. In many countries (e.g., Germany and Japan), banks extend their control and monitor debtors by directly owning company shares and appointing directors (Lin et al. 2009). The existing empirical studies show that the bank relationship has ambigu-ous effects on corporate decisions and value. Many researchers (e.g., Hoshi et al. 1991) agree that bank ownership provides better capital access to and better monitoring for companies. But some studies (e.g., Lin et al. 2009) suggest that banks do not exercise enough monitoring over their loans.

Dividend Policy

Easterbrook (1984) and Jensen (1986) make an agency theory argument where managers pay dividends to reduce the firm’s discretionary free cash flow that could be used to fund suboptimal investments that benefit managers but diminish shareholder wealth.

Using Canadian firms where managers own a large amount of voting stock, Eckbo and Verma (1994) found that cash dividends decrease as the voting power of owner-managers increases, and are almost zero when owner-owner-managers have absolute vot-ing control of the firm. The evidence supports a conflict of interest across various shareholder groups, possibly reflecting a combination of heterogeneous dividend tax rates and managerial preference for free cash flow. Short et al. (2002) also indicate that a positive association exists between dividend payout policy and institutional ownership, while a negative association exists between dividend payout policy and

managerial ownership.8 Iturriaga and Crisostomo (2010) found that dividends play a

disciplinary role in firms with fewer growth opportunities by reducing free cash flow under managerial control.

Jensen et al. (1992) examined the determinants of cross-sectional differences in insider ownership, debt, and dividend policy, and found that insider ownership has a negative effect on firms’ debt and dividend levels. These results indicate that firms set dividend levels that permit managers to finance expected investment internally. If dividend policy corresponds to managerial projections of future investment opportunities, firms can main-tain stable dividends and obmain-tain needed equity financing internally. Myers and Majluf (1984) argued that friction in capital markets leads to competition between dividends and investment projects as potential uses of profits. They showed that firms can build up financial slack by restricting dividends when investment requirements are modest. The cash saved is held as marketable securities or reserve borrowing power.

Farinha (2003) examined the agency theory explanation for the cross-sectional distri-bution of dividend payout in the U.K. He found a strong U-shaped relationship between dividend payout and insider ownership. He asserted that cash payments to shareholders might help reduce agency problems by increasing the frequency of raising external capital and associated monitoring by investment bankers and investors, or by eliminating free cash flow. Consistent with the agency cost explanation, Gugler (2003) found that in state-controlled firms, smooth dividends have large target payout ratios and are most reluctant to cut dividends, despite the potential costs involved for shareholders. In contrast, family-controlled firms pursue a significantly different dividend policy, showing no smoothing dividends, lower target payout ratios, and reluctance to cut dividends. In addition, they found that firms with low growth opportunities and smooth dividends have larger target payout ratios irrespective of who controls the firm. Lin et al. (2010) also showed that

cash dividend preference is positively related to the proportion of state-owned shares and negatively related to the proportion of tradable shares.

In sum, a number of researchers have also examined the importance that managers and investors attach to dividend policy, and have explained firms’ dividend behavior. However, most of these studies involve U.S. data or data from other developed markets, such as the U.K., Canada, and continental Europe, but less research is conducted in emerging markets. In addition, research has neglected the potential relationship between dividend policy and board-appointed bankers. This is especially the case for Taiwanese firms where the ownership structures and institutional framework are different from those of the above-mentioned countries.

The Relationship Between Bankers on the Board and Dividend Policy

While the literature has documented empirical evidence on the relation between dividend policy and management ownership, the potential relationship between dividend policy and the board of directors has been somewhat neglected. The agency cost perspective uses dividends in reducing the agency problem between managers and stockholders. That is, dividend payment reduces the discretionary funds available to managers for perquisite consumption and helps address the manager–stockholder conflict (Easterbrook 1984). In addition to the conflict between stockholders and managers, a similar conflict also exists between stockholders and creditors, since creditors’ interests often differ from those of shareholders. Therefore, stockholders may expropriate wealth from creditors by paying themselves dividends. In this situation, creditors may try to contain this problem through restrictions on dividend payment in the bond indenture.

The bank holdup theory suggests that benefits from monitored debts decrease when firm growth prospects improve. If firms’ moral hazard problems are severe, banks can monitor and control clients’ firms so that monitoring benefits overwhelm costs. When firm quality and growth opportunities improve, the monitoring benefits decrease (Dia-mond 1991). Rajan (1992) also suggests that such holdup behavior by banks affects firm incentives if banks are unchecked; consequently, firms that have better growth prospects prefer more public debts to monitored debts. In contrast, the information production literature emphasizes that high-growth firms prefer monitored debts to public debts. Yosha (1995) argues that relationship-based financing prevents firms from disclosing proprietary information to product-market competitors, and at the same time, produces positive information for high-growth firms. However, bank holdup theory ignores the fact that growth-based firm valuations tend to hamper the use of public debt, whereas the information production literature ignores the actuality that bank rent extraction especially hurts high growth firms. Wu et al. (2009) point out that funding competition from new equity as an effective natural mechanism solves this concern. Using Japanese data, they show that high-growth firms raise more new equity than do low-growth firms and use more equity relative to bonds in external finance.

Given the profound influence of family block holders on the board composition in Taiwan, internal governance systems are significantly weaker. According to agency theory, large family owners may engage in activities that are in their best interest but not necessarily in the best interest of other shareholders who may not have any voice in the governance of the corporation and only limited formal or informal means to protect their interests. Excess cash flows that would be used for empire building through acquisi-tions in unrelated areas or in projects of questionable value are returned to shareholders

through dividends, thus reducing agency problems (Yoshikawa and Rasheed 2010). When bankers are appointed to the board, they may serve as firms’ monitors to help alleviate agency problems. Thus, firms with bankers on the board may not necessarily pay more dividends to reduce agency costs. The following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 1: A banker on the board is negatively associated with the firm’s divi-dend payout.

Research Methodology

Measuring Dividend Policy (DPi,t)

DPi,t represents firms’ dividend policy, measured in two ways. Specifically, this study

sets the first dividend variable, the dividend dummy (DP1i,t), at 1 for firm i in year t if the

annual amount of dividends paid is positive, and 0 otherwise. The other dividend variable

is the dividend payout ratio (DP2i,t), obtained by scaling dividends per share by earnings

per share for firm i in year t. For the first measure, we use the logistic regression; for the other measure, we run the ordinary least squares (OLS) test.

Measuring Bankers on the Board (BCi,t)

This paper uses two proxies for bankers on the board (BCi,t). The first is a dummy

vari-able (BC1i,t), which equals 1 if the firm has a banker on its board and 0 if it does not. The

second is the number of banker directors divided by the size of the board (BC2i,t).

Control Variables

We utilized several controls in our analyses. First, the relationship between growth op-portunity and dividend payout is mixed. According to the signaling theory, firms with high levels of growth opportunities face more information asymmetries (Miller and Rock 1985). Therefore, firms with high growth opportunity have incentives to use permanent positive cash flow shocks to increase dividends and signal higher expected earnings. An alternative view to the signaling theory is the agency costs of free cash flow theory. This theory suggests that managers will not invest to maximize shareholder wealth (Jensen 1986). Thus, a dividend increase can limit possible future suboptimal investment, espe-cially for low growth opportunity firms, which have fewer positive net present value (NPV) projects. Furthermore, because growth opportunities are unobservable, many empirical

definitions exist. To proxy for growth opportunities, this study uses MTBi,t, estimated by

the ratio of market value to the book value of assets. This proxy derives from Chung and Pruitt (1994) and is widely used in research as a measure of growth opportunities.

Previous literature has documented the negative effect of leverage on dividend pay-ment. For example, Rozeff (1982) found that firms with higher leverage pay lower dividends to evade the cost of raising firm external capital. Abor and Biekpe (2007) also argued that debt financing is a dominant factor in corporate decisions in some emerging

countries. Therefore, we add the debt ratio (DEBTi,t) as a control variable, calculated as

total debts divided by total assets, and expected to be negatively related to dividends. Based on the agency theory, institutional shareholders prefer a free cash flow distrib-uted in the form of dividends to reduce the agency costs of free cash flow (Eckbo and Verma 1994). Short et al. (2002) also indicate that institutional shareholders counter

managers’ preference for retaining excessive cash flow to force managers to pay out dividends by virtue of their voting power. Following Francis et al. (2005), this study

measures institutional ownership (INSTi,t) as the proportion of common shares owned

by domestic investment funds, domestic banks, and foreign investors. The coefficient on

INSTi,t is expected to be positive.

SIZEi,t is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. Based on Lloyd et al. (1985)

and Vogt (1994), firm size plays a role in explaining the dividend payout ratio of firms. They found that larger firms tend to be more mature and thus have easier access to the capital markets, which reduces their dependence on internally generated funding and al-lows for higher dividend payout ratios. According to their perspective, this study expects

that larger firms offer relatively greater dividends, and thus, a positive sign for SIZEi,t.

Yoshikawa and Rasheed (2010) indicate that family owners can exert their influence through their representatives on the board. In addition, family owners pay dividends to minor-ity shareholders. As treating minorminor-ity owners fairly is more valuable in countries where legal protection for minority shareholders is weak, establishing a reputation for good treatment of minority shareholders will enable these firms to access equity markets in the future (La Porta

et al. 2000). Therefore, we use FDi,t, measured as the presence of family directors on the board,

as a control variable, and expect the coefficient on FDi,t to be positive.

Almeida et al. (2004) argue that higher cash holding generally increases firms’ capac-ity to undertake profitable investment opportunities. Therefore, the interaction variable

BCi,t_IOi,t is included in the model as a control variable to capture the effect of cash flow/

investment opportunities on dividend policies of those firms that have bankers on the

board, relative to those that do not. We expect a positive coefficient on BCi,t_IOi,t, which

implies that dividends increase when the investment opportunities increase in firms with bankers on the board versus firms without bankers on the board.

Finally, in order to control for the industry, exchange, and year effects, we use one industry dummy variable, one exchange dummy variable, and four-year dummy variables.

Empirical Specification

To examine the relationship between bankers on the board and dividend policy, this study uses regression models as follows. We expect that bankers on the board negatively cause

dividends. The expected signs for BC1i,t and BC2i,t are therefore negative.

DPi t o BC MTB DEBT INST SIZE

i i t i t i t i t i t , =β β+ 1 1, +β2 , +β3 , +β4 , +β5 , + ββ β β β β 6 7 8 9 FD INDUSTRY EXCHANGE BC IO YEAR i t i t i t i t i t t t , , , , _ , + + + + kk i t =

∑

+ 2003 2006 ε, (1)DPi t o BC MTB DEBT INST SIZE

i i t i t i t i t i t , =β β+ 1 2, +β2 , +β3 , +β4 , +β5 , + ββ β β β β 6FD 7INDUSTRY 8EXCHANGE 9BC IO YEAR i t i t i t i t i t t t , + , + , + ,_ , + kk i t , =

∑

+ 2003 2006 ε, (2) whereDpi,t = dividend policy measures for firm i in year t, including the dividend dummy

BC1i,t = the bankers on the board dummy, which equals 1 if the firm has a banker on

its board in year t, and 0 otherwise;

BC2i,t = the percentage of banker directors for firm i in year t;

MTBi,t = the market-to-book ratio for firm i in year t;

DEBTi,t = the ratio of total debt to total assets for firm i in year t;

INSTi,t= the percentage of common shares held by institutional investors;

SIZEi,t = the natural logarithm of total assets for firm i in year t;

FDi,t = the family director dummy, which equals 1 if firm i has one or more family

directors on the board, and 0 otherwise;

INDUSTRYi,t = the industry dummy, which equals 1 if firm i belongs to electronics

industry, and 0 otherwise;

EXCHANGEi,t = the exchange market dummy, which equals 1 if firm i belongs to the

exchange market, and 0 otherwise;

IOi,t = the investment in fixed assets (change in the net fixed assets plus depreciation)

dividend by the beginning of the year net fixed asset for firm i in year t; and

YEARt = the year dummy, which equals 1 for a specific year, and 0 otherwise.

Sample Selection and Data Source Sample Selection

This study analyzes all companies listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TSE) and

over-the-counter (OTC) stock market over a five-year period from 2003 to 2007.9 The sample

is obtained based on the following criteria:

1. Firms with a fiscal year ending other than the calendar year-end are deleted. 2. In line with other studies (e.g., Peasnell et al. 2005; Vafeas 2005), this study

excludes companies in the banking industry because of their substantially different types of corporate investment and accounting data.

3. Firms with substantial events, such as merging, declaring bankruptcy, or being unlisted during the sample period, are excluded.

4. Observations with incomplete data are excluded.

During this sample period, 5,063 observations satisfy these selection criteria. Of these observations, 232 (4.58 percent) are bankers on the board and 4,831 (95.42 percent) are not bankers on the board. The proportion of observations with bankers on the board in Taiwan is rare. Given the limited number of banker directors’ observations, this study further adopts the matched-sample approach and identifies two firms without bankers on the board that match each firm with bankers on the board (i.e., on a two-to-one basis) in

the same period, in the same industry, and of similar total assets (size).10 The technique

employed helps control the influences of industry and size factors on banker directors.

Four observations are eliminated because no suitable match is located.11 The final sample

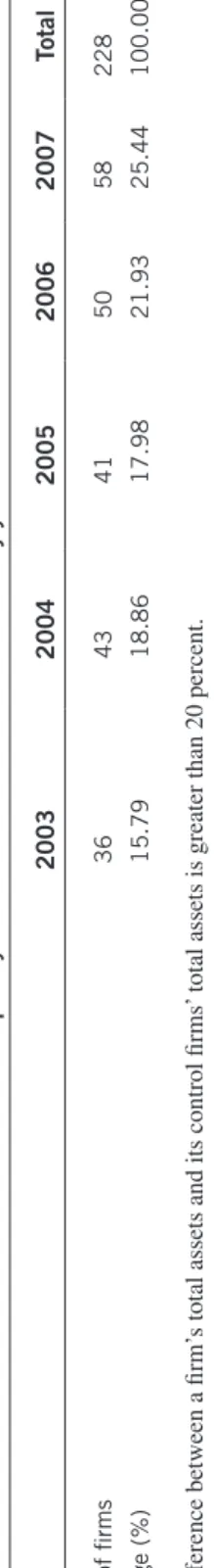

size comprises 684 observations.12 The sample selection process is reported in Panel A of

Table 1. Panel B lists the frequency of firms with bankers on the board within respective sample years. The number of companies with bankers on the board increases over time, suggesting that banks play a role on the board of directors for firms. Table 2 illustrates the industry distribution of sample companies. The electronics industry firms represent the highest percentage (78.07 percent = 534/684). All but the electronics industry comprise less than 10 percent of the sample firms.

Table 1. Sample details

Panel A: Summary of sample selection procedures

Criteria

Number of obs.

Initial sample

5,499

Less: observations with noncalendar fiscal year

-end

10

Observations with banking industry

218

Observations that involved in substantial events

207

Observations with incomplete data

1

Total number of observations

5,063

Dividing into:

Observations with bankers on the board

232 (4.58%)

Observations without bankers on the board

4,831 (95.42%)

Observations with bankers on the board from 2003 to 2007

232

Less: observations for which no control firm identified

4

Number of observations with bankers on the board

228

Add: Number of observations matched on period, industry and size

456

Final sample

684

Panel B: Frequency of firms with bankers on the board by year

Year 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Total Number of firms 36 43 41 50 58 228 Percentage (%) 15.79 18.86 17.98 21.93 25.44 100.00 Note: Dif

ference between a firm’

s total assets and its control firms’

To order reprints, call 1-800-352-2210; outside the United States, call 717-632-3535. Kroszner, R.S., and R.G. Rajan. 1997. “Organization Structure and Credibility: Evidence from

Commercial Bank Securities Activities Before the Glass-Steagall Act.” Journal of Monetary Economics 39, no. 3 (August): 475–516.

Kroszner, R.S., and P.E. Strahan. 2001. “Bankers on Boards: Monitoring, Conflicts of Interest, and Lender Liability.” Journal of Financial Economics 62, no. 3 (December): 415–452. Lai, Y.H.; C.P. Chen; and C.C. Ho. 2008. “Determinants of Bankers on Boards in Taiwan:

Agency Costs and Lenders’ Conflict of Interest Hypotheses.” Journal of Management 25, no. 1 (February): 1–30 (in Chinese).

La Porta, R.; F. López de Silanes; and A. Shleifer. 1999. “Corporate Ownership Around the World.” Journal of Finance 54, no. 2 (April): 471–517.

Lin, X.; Y. Zhang; and N. Zhu. 2009. “Does Bank Ownership Increase Firm Value? Evidence from China.” Journal of International Money and Finance 28, no. 4 (June): 720–737. Lin, Y.H.; J.R. Chiou; and Y.R. Chen. 2010. “Evidence from China’s Privatized State-Owned

Enterprises.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 46, no. 1 (January–February): 56–74. Lloyd, P.; J. Jahera; and D. Page. 1985. “Agency Costs and Dividend Payout Ratios.” Quarterly

Journal of Business and Economics 24, no. 3 (Summer): 19–29.

Lorsch, J.W., and E. Maclver. 1989. Pawns and Potentates: The Reality of America’s Corporate Boards, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Mace, M.L. 1971. Directors: Myth and Reality, Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Miller, M.H., and F. Modigliani. 1961. “Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares.”

Journal of Business 34, no. 4 (October): 411–433.

Miller, M.H., and K. Rock. 1985. “Dividend Policy Under Asymmetric Information.” Journal of Finance 40, no. 4 (September): 1031–1051.

Myers, S.C., and N.S. Majluf. 1984. “Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have.” Journal of Financial Economics 13, no. 2 (June): 187–221.

Peasnell, K.V.; P.F. Pope; and S. Young. 2005. “Board Monitoring and Earnings Management: Do Outside Directors Influence Abnormal Accruals?” Journal of Business Finance and Ac-counting 32, nos. 7–8 (September–October): 1311–1346.

Rajan, R. 1992. “Insiders and Outsiders: The Choice between Relationship and Arm’s Length Debt.” Journal of Finance 47, no. 4 (September): 1367–1400.

Rozeff, M.S. 1982. “Growth, Beta and Agency Costs as Determinants of Dividend Payout Ra-tios.” Journal of Financial Research 5, no. 3 (Fall): 249–259.

Schooley, D.K., and L.D. Barney. 1994. “Using Dividend Policy and Managerial Ownership to Reduce Agency Costs.” Journal of Financial Research 17, no. 3 (Fall): 363–373.

Short, H.; H. Zhang; and K. Keasey. 2002. “The Link Between Dividend Policy and Institutional Ownership.” Journal of Corporate Finance 8, no. 2 (March): 105–122.

Skogsvik, K. 2005. “On the Choice-Based Sample Bias in Probabilistic Business Failure Predic-tion.” SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Business Administration, no. 2005:13. http://swoba. hhs.se/hastba/papers/hastba2005_013.pdf.

Vafeas, N. 2005. “Audit Committees, Boards, and the Quality of Reported Earnings.” Contem-porary Accounting Research 22, no. 4 (Winter): 1093–1122.

Vogt, S.C. 1994. “The Cash Flow/Investment Relationship: Evidence from U.S. Manufacturing Firms.” Financial Management 23, no. 2 (Summer): 3–20.

Wu, X.; P. Sercu; and J. Yao. 2009. “Does Competition from New Equity Mitigate Bank Rent Extraction? Insights from Japanese Data.” Journal of Banking and Finance 33, no. 10 (Octo-ber): 1884–1897.

Yoon, P.S., and L.T. Starks. 1995. “Signaling, Investment Opportunities, and Dividend An-nouncements.” Review of Financial Studies 8, no. 4 (Winter): 995–1018.

Yosha, O. 1995. “Information Disclosure Costs and the Choice of Financing Source.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 4, no. 1 (January): 3–20.

Yoshikawa, T., and A.A. Rasheed. 2010. “Family Control and Ownership Monitoring in Family-Controlled Firms in Japan.” Journal of Management Studies 47, no. 2 (March): 274–295. Young, M.; M.W. Peng; D. Ahlstrom; G. Bruton; and Y. Jiang. 2008. “Corporate Governance in

Merging Economies: A Review of the Principal–Principal Perspective.” Journal of Manage-ment Studies 45, no. 1 (January): 196–220.