國 立 交 通 大 學

管理科學系

博士論文

No. 006

網路訂價公平性認知

Perceived Fairness of Pricing on the Internet

研 究 生 : 張清德

指導教授 : 黃仁宏 教授

國 立 交 通 大 學

管理科學系

博士論文

No. 006

網路訂價公平性認知

Perceived Fairness of Pricing on the Internet

研 究 生 :張清德

指導教授委員會 :楊 千 教授

林富松 教授

黃仁宏 教授

指導教授 :黃仁宏 教授

中 華 民 國 九十三 年 五 月

網路訂價公平性認知

Perceived Fairness of Pricing on the Internet

研

究 生:張清德 Student:Ching-Te Chang

指導教授:黃仁宏

Advisor:Jen-Hung Huang

國立交通大學

管理科學系

博士論文

A Dissertation

Submitted to Institute of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of

Doctor

of

Philosophy

in

Management

May 2004

Hsin-Chu, Taiwan, Republic of China

中華民國九十三年五月

網路訂價公平性認知

研究生:張清德

指導教授 :黃仁宏

楊 千

林富松

國立交通大學管理科學研究所博士班

摘 要

價格調整,認知上是否公平,在經濟及行銷文獻上,是探

究甚多之主題。本文就網路上,消費者對訂價是否公平之認

知,由消費者面向予以調查,從:擴大市場力,網路上之公

平價格,訂價機制,差別取價方法及差價管理等五個方向做

探討。

從台灣

276 個問卷調查中,得知網路上之價格若與傳統行

銷管道之價格相同,則被認為是不公平,接受調查者認為,

網路上不同之訂價機制,是公平的,而差別取價及差價管理

被認為是不公平的。

關鍵字:網路 訂價 公平

Perceived Fairness of Pricing on the Internet

Student:Ching-Te Chang

Advisor : Jen-Jung Huang

Chain Yang

Fu-Song Lin

Institute of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

The perceived fairness of price changes has been a

subject of much inquiry in economic and marketing literature.

This paper examines consumers’ perceptions of the fairness of

pricing on the Internet. Increased market power, fair prices on the

Internet, pricing mechanisms, methods of price discrimination

and yield management are investigated from a consumer’s

perspective. Results obtained from 276 questionnaires collected

in Taiwan indicate that the Internet prices that equal those in the

traditional channels are perceived to be unfair. Respondents

considered various pricing mechanisms on the Internet to be fair

while many practices of price discrimination and yield

management were perceived to be unfair.

誌

謝

博士論文之完成,首先感謝指導教授-黃仁宏教授,由

於黃教授的一路帶領,才能突破困苦,種種心路歷程,點滴

感激。其次要感謝口試委員何照義教授、韋端教授、楊千教

授、褚宗堯教授、林富松教授、祝鳳岡教授之指正,使得論

文紮實一體。

博士課程期間,楊千教授一再鼓勵,要堅忍持志,交

通大學師長們,朱博湧教授、王耀德教授、許和鈞教授、張

力元教授、王克陸教授、王淑芬教授、謝國文教授、姜齊教

授等在研究方法之嚴格訓練,使得自己頗有自信及心得,非

常感謝。能在交通大學張俊彥校長帶領的這些第一流學者下

受教,真是人生有幸!

另外,要感謝我的父親張順來先生,雖然他已逝去二

十三年,但他的寬厚、不計較且不佔便宜的心胸,影響我一

輩子;我的母親張賴阿柔女士,溫賢睿智,含辛帶領七子女,

張月英、張月真、張月照、張清惠、張清雲、張清發,真是

令人敬佩感恩;內人及摯愛盧秀娟女士,是一賢內助,踏實

勤儉持家,又時時敦促,是我完成博士學位之最大助力;本

論文也要獻給我的兩個兒子:張鼎聲、張鈺聲,他們的傑出

Table of Contents

中文摘要

...i

英文摘要

...ii

誌謝

...iii

目錄

...v

List of Tables ...vii

List of Figures ...viii

Chapter

1.

Introduction ...1

1.1 Background...1

1.2 Motives and Objectives of This Study...2

1.3 Organization of the Dissertation...3

Chapter 2. The Fairness of Pricing and Literature Review ...4

2.1 Fairness ...4

2.1.1 Distributive justice...5

2.1.2 Procedural justice...7

2.2 Pricing ...9

2.2.1 Pricing

dynamics ...9

2.2.2 Bundling and prospect theory...10

2.3

Types and Taxonomy of dynamic pricing...12

Chapter 3. Pricing Mechanisms and Methods on The Internet .15

3.1

Increased Market Power ...16

3.2

Fair Prices on The Internet ...16

3.3 Pricing

Mechanism...17

3.4 Price

Discrimination...18

3.5 Yield

Management...19

3.6

The Framework of The Survey...20

Chapter 4. Methodology and Survey...21

4.1 Q-methodology...21

4.2 The

Survey...22

Chapter 5. Results of The Survey ...23

5.2 Fair Prices on the Internet...25

5.3 Pricing Mechanism ...27

5.3.1 Auction...27

5.3.2 Group-Buying discount...29

5.3.3 Priceline model ...31

5.3.4 Negotiation...32

5.4 Price Discrimination ...33

5.4.1 Random discounting...33

5.4.2 Couponing ...34

5.4.3 Geographic discrimination ...35

5.4.4 Discounting to new or loyal customers...36

5.4.5 Discrimination based on price sensitivity ...37

5.5 Yield

Management...38

5.6

Summary of the Results...40

Chapter 6. Conclusions and Suggestions...42

6.1 Conclusions...42

6.2 Suggestions ...43

References...45

Appendix...50

自傳

...61

博士班研究期間著作一覽表

...64

List of Tables

List of Figures

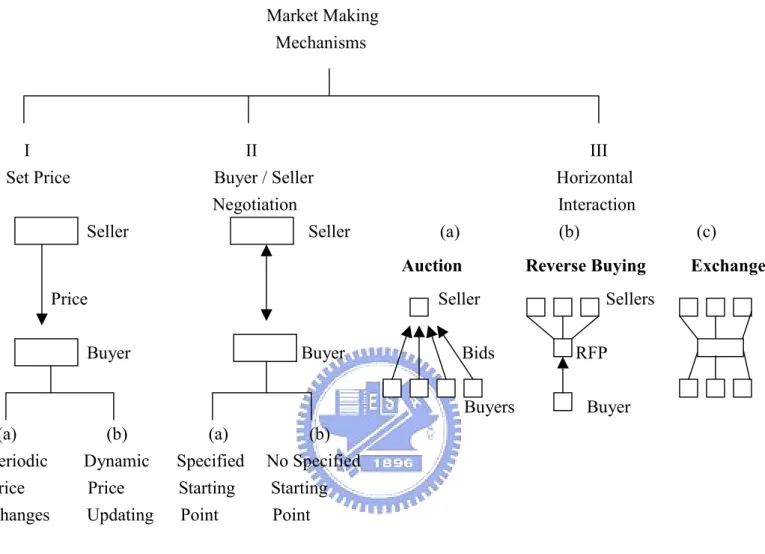

Figure 1. Three Types of Marketing Making Mechanisms ...13

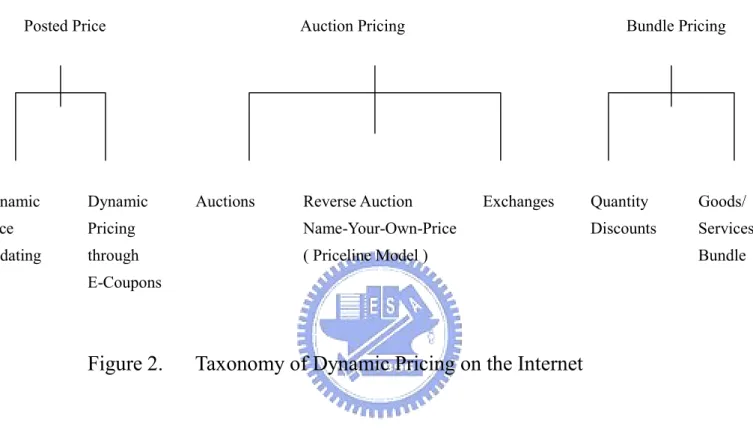

Figure 2. Taxonomy of Dynamic Pricing on the Internet ...14

Figure 3. The Framework of the Survey of Perceived Fairness of

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Applying the principles of economics to setting prices on the Internet can be precarious to the reputation of a firm. Amazon.com, the cyberspace retailer,

encountered problems when some customers who had bought DVD movies began to compare prices on online discussion boards. News media picked up on the disparity and consumer outcry erupted. Amazon.com finally refunded 6,896 customers an average of $3 (Kong, September 29, 2000).

Amazon.com claimed that it had been performing random pricing tests, randomly offering the same DVDs at various prices. An Amazon.com spokesman claimed that the tests were useful in determining a price point – the right balance between how much Amazon.com could charge while maintaining a good sales volume. However, Amazon.com faced allegations that the various prices were based on customer data it obtained when the customers visited its site. Such data might include a person's mailing address and how much he or she might have previously spent at Amazon.com. Amazon.com was accused of charging their loyal customers higher prices than new customers.

Setting prices based on shoppers' incomes or buying habits is known as “dynamic pricing” (Kannan and Kopalle, 2001). Dynamic pricing is not new.

Retailers frequently charge more for goods in stores in better neighborhoods, or more in areas of less competition. For example, Wal-Mart’s prices in remote locations with no direct competition from a large discounter were 6% higher than that at locations where it was next to a Kmart (Foley et al., 1996). The price of a can of Coke varies with the type of outlet, from DM 2.20 in newsstand in a train station, to DM 0.64 in a large supermarket (Dolan and Simon, 1996). Airlines are also known to change prices

frequently according to demand and the timing of a reservation. Very few people seem to complain about such pricing practices.

On the Internet, opportunities for dynamic pricing are greater for at least two reasons – customer information can be more easily collected and list prices can be more easily changed (Dolan and Moon, 2000). Furthermore, it is easier to check competitors’ prices and availability of products. With such information, the dynamics of demand and supply can be better understood and prices adjusted accordingly.

The Internet supports not only the mechanism whereby sellers set prices, while consumers “take it or leave it,” but also other mechanisms of transaction, such as group-discounting, negotiation, auction and reverse auction. Each type of transaction has its pros and cons from economic perspectives. For example, Wang (1993)

compared posted-price selling with auctions in a traditional retail setting and found that auctions were optimal in most situations. Auctions would be even more attractive on the Internet since the associated costs would be much lower than those of auctions in the real world.

Most mutually satisfying exchange relationships require fairness. The perception of fairness is more critical on the Internet than in traditional channels, since feasible practices in brick-and-mortar stores, such as that adopted by Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., may not be tolerated on the Internet. As Kahneman et al. (1986b, p. S299) stated, “The rules of fairness cannot be inferred either from conventional economic principles or from intuition and introspection,” but should be empirically tested.

1.2 Motives and Objectives of This Study

This dissertation aims to examine consumers’ perceptions of fairness of pricing on the Internet, addressing increased market power, fair prices, pricing mechanisms, price discrimination and yield management. The pricing of hotel rooms are examined

for two reasons: first, most people have experience using the service; and second, many hotels have their own websites for taking reservations. Since many studies have examined the relationship between perceived fairness and purchasing intentions, this study focuses on fairness. Previous studies have shown that perceived unfairness leads to distrust and diminished shopping intentions both off and on the Internet (Campbell, 1999; Huang, 2001; Kahneman et al., 1986a, 1986b; Piron and Fernandez, 1995).

1.3 Organization of the Dissertation

This dissertation, including six chapters, is organized as follows.

Chapter one is introduction, which describes the background of some cases and previous researches that are related to fairness on the Internet. Chapter two review related literature about fairness. Chapter three describes the pricing mechanisms and methods on the Internet. Chapter four states the methodology. Chapter five reports the results of survey. Chapter six reaches conclusions and draws suggestions for future studies.

Chapter 2 The Fairness of Pricing and Literature Review

The same hotel chain as well as Wal-Mart and Car-rental companies charge different prices for different locations. Very few people seem to complain about such pricing practices. Why is it that Amazon.com’s pricing perceived as being unfair? Is it fair that some customers pay corporate rates and some pay regular rates for a hotel stay? Is it fair that a hotel raise price when a nearby competitor is closed for renovation? Can a hotel alleviate unfair perception when the differential rates are employed or when the rate for a room is raised for increased demand? These

questions indicate that perceived fairness of price is a complex issue. Answering these questions requires an understanding of the concepts and theories of fairness. 2.1 Fairness

In any exchange relationships, questions of fairness surface. The study of fairness has engaged researchers from many disciplines such as economics,

psychology, marketing, organization, and social psychology. Researchers generally think of exchange transactions as involving both an outcome and a process by which that outcome is achieved. In the case of pricing, the outcome in question is the selling price of a good or service: is it the price higher or lower than its fair price? The process of an exchange transaction consists of the assessment procedures used to make the decision; for example, the considerations that go into setting the price. Fairness judgments regarding outcomes are usually studied under the term of

distributive justice, whereas those involving the process are labeled procedure justice. (Adams, 1965; Lind & Tyler, 1988; Colquitt et al., 2001) Perceived price fairness has been identified as one psychological factor that exerts an important influence on consumers’ reactions to prices ( Kahneman 1986 a.b. )

An understanding of principles of price fairness, one should understand the concept of distributive and procedural justice, as well as equity theory and dual entitlement. ( Cox , 2001)

2.1.1 Distributive justice

Most mutually satisfying exchange relationships require fairness, or distributive justice, as it is called in social psychology (Jasso, 1980; Messick and Sentis, 1979). Deutsch (1975) contended that equity, equality, and needs serve as distribution rules for determining perceptions of exchange fairness and different conditions give rise to use of the different allocation rules. Equity rather than equality or need is the dominant principle of distributive justice in cooperative relations that focus on economic productivity. According to Adams’s (1965) equity theory, what people were concerned about was not the absolute level of outcomes per se but whether those outcomes were fair. One way people determine whether an outcome was fair was to calculate the ratio of one’s “input” to one’s outcome, and compare the ratio with that of the other. Oliver and Swan's (1989) survey of automobile purchasers’ inputs to and outcomes from the sale transaction and their perceptions of the inputs and outcomes of the salesperson revealed that fairness dominates satisfaction judgments. Satisfaction, in turn, is strongly related to the consumer’s intention cognition. Discrepancies between actual outcomes and “just” outcomes produce emotional distress, motivating actors to restore a sense of fairness, such as refusing to deal with the company again.

Although principles of justice come from social norms and are objective features of social exchange, perceptions of fairness are inherently subjective. Self-interest and perceptual biases strongly influence fairness judgments. Individuals are more likely to find justice in distribution rules that favor their own position (Messick and

Sentis, 1979). Comparing the scenario in which a subject works seven hours while another works ten hours with another scenario in which a subject works ten hours while the other works seven hours reveals that a significantly greater proportion of subjects in the former case than in the latter case consider equal economic outcomes to be fairest. When the other worker has worked for seven hours and has been paid $25, subjects judge the fairest amount for themselves to be $37.07 for ten hours of work. However, when the subjects have worked seven hours and been paid $25, they judge that the fairest amount for the other worker to be $32.79 for working 10 hours of work. Similarly, a pricing mechanism is likely to be considered fairer by those respondents who receive lower prices than those who have to pay higher prices.

The perceived fairness of pricing has been extensively studied in economic and marketing literature (Campbell, 1999; Dickson and Kalapurakal, 1994; Kahneman et al., 1986a, 1986b; Seligman and Schwartz, 1997). Kahneman et al. (1986a) surveyed randomly selected adults from Vancouver and Toronto metropolitan areas regarding the fairness of various hypothetical business transactions. They contended that community norms of what constitutes a fair price are used to make judgments about fairness. They proposed the principle of “dual entitlement,” which states that buyers are entitled to the terms of the reference prices and firms are entitled to their reference profits. When the reference profit of a firm is threatened, increasing prices to protect that profit is perceived to be fair. A firm need not pass along savings to buyers when its costs decrease. However, a firm’s exploiting increased market power, such as during a supply shortage, is unacceptable. Many studies have confirmed and extended these findings (Gorman and Kehr, 1992; Kachelmeier et al., 1991; Schein, 2002; Kristensen, 2000).

One of the focuses of pricing study in marketing has been the role of internal reference price held by buyers in evaluating the utility of a purchase ( Rajendran and

Tellis, 1994). By comparing the actual price with the internal reference price,

consumers form the fairness perception of prices. They found that fairness perceptions are driven by comparisons to past prices, competitor prices, and perceived costs. Consumers systematically underestimate the effects of inflation, even when provided with explicit inflation rates, current prices, and historical data. When looking across competitors, consumers tend to attribute store price differences to profit rather than to cost. From a consumer’s perspective, price differences appear fairest only if they can be attributed to quality differences. Other differences such as suppliers’ volume discount, which is beyond the store’s control, may be judged as unfair. Many costs are ignored and some costs are viewed as unfair, leading to high and sticky profit estimates that contribute to perceptions of unfairness. In other word, consumers’ internal reference prices and fairness judgments, just as other social exchange, are strongly influenced by self-interest and perceptual biases.

Broadly viewed, the concept of distributive justice is concerned with the distribution of the conditions and goods which affect individual well-being. “ Well-being” broadly to include its psychological, physiological, economic, and social aspects.( Deutsch, 1975 )

2.1.2 Procedural justice

While the distributive justice of exchange relationships affect the perception of fairness, the process that comes to the conclusion is also important in determining the perception of fairness. For example, research on defendant reactions to their

experiences in Chicago’s traffic court revealed that a positive outcome did not always result in a satisfied defendant (Lind and Tyler, 1988).

Procedures should (a) be applied consistently across people and across time, (b) be free from bias, (c) ensure that accurate information is collected and used in making

decision, (d) have some mechanism to correct flawed or inaccurate decisions, (e) conform to personal or prevailing standards of ethics or morality, and (f) ensure that the opinions of various groups affected by the decision have been taken into account.

In the context of pricing, consumers care not only the price they have to pay but also how the price is derived. “Dual Entitlement” not only deals with distributive justice: fair price and fair profit (Cox, 2001), it also deals with the processes which are judged by consumers for the fairness of price (Maxwell, Nye and Maxwell, 1999). The same price increase can be perceived as fair or unfair, depending on whether the process meet society norms or not. For example, 79% of the respondents found it acceptable for a local grocer to maintain their profits by raising the price of lettuce by 30 cents per head to cover the increased cost. However, 79% of the respondents found it unfair for a grocery store to raise price immediately on the current stock of peanut butter when the grocery owner hears that the wholesale price of peanut butter has increased (Kahneman et al., 1986). Amazon’s customers were not angry about the prices per se, but about the way the prices were set –– loyal customers pay more.

The stream of research on fairness concentrates on the perceived fairness of adjusting prices to respondents (Kahneman et al. 1985a; Campbell 1999). Only a limited number of studies have examined the perceived fairness of varying prices across the customers, i.e., differential prices. Feinberg et al. (2002) built and tested models to demonstrate that consumers’ preferences for their favored firm declines if the firm offers a special price to another firm’s present customers but not to their own present customers. As cited in Cox 1999, pointed out that, for basic items such as groceries, an individual paying a higher price than a lower-income buyer will perceive the situation as being fair, whereas, for luxury items such as imported bottled water, a lower-income individual pays lower prices will be perceived as being unfair by the higher-paying individual.

Shaw, Wild and Colquitt (2003), in a meta-analysis, found strong effects of explanation on fairness perception, and the effect are moderated by outcome favorability.

Previous research demonstrates that people evaluate their own inputs as more important than those of others, and that those in power-advantaged positions perceive exchange outcomes as more fair than do those in disadvantaged positions (Molm, Takahashi, and Peterson, 2003).

2.2 Pricing

Pricing is a very important role in marketing and even in the integration of management. There are lots of related topics have been studied and many executives have taken action for decisions in practices.

2.2.1 Pricing dynamics

The pricing methods including mark-up pricing, target-return pricing, perceived value pricing, value pricing, going-rate pricing and whole transaction pricing.

( Kotler,2002)

But the recent years, because of the software, hardware and dynamics of interface network intelligence, the new pricing dynamics on the internet was hugely be used, so that the probe of consumers’ perception of fairness and pricing methods on the Internet is an interesting and timing issue.

Nagle and Holden (1995) presented the strategy and tactics of pricing decision and dynamics of pricing for marketing transaction. Mitchell (1990), stressed on the issues of the prompt increasing oil price just after the Iraq attacked Kuwait, and proposed that it should be carefully reviewed on the fairness, explanation, consumers’

communication, low-visibility and legal contract or regulation on the mutual sides of pricing issues. Nagle and Holden (1995), Rajendran and Tellis (1994) studied about the reference prices and psychological pricing. Monroe (1973) proposed the Buyers’ subjective perceptions of price. Yadav and Monroe (1993) researched the perceive savings in a bundle price and bundle’s transaction value. Anonymous (1999) demonstrated the ability of quick and case analyzing the retail traffic in websites., collecting consumers’ preferences and demographic data facilitate, supporting the real-time setting of dynamic pricing policies. Geng et al. (2001) discussed the on-line auction . Kauffman and Wang (2001) studied the group-buying discounts on the internet. Kimes (2002) analyzed yield management related the consumer perceived fairness and showed that many survey respondents considered the use of yield management in the hotel industry to be very unfair.

Economic consideration is only one of factors that need to be taken into account when setting prices off or on the internet. Consumers’ perception of fairness is an important issue that has to be borne in mind. Although internet offer sellers the opportunities to practice price crimination, it is also easier for consumers to compare prices and challenge the practices of pricing. Furthermore, internet is a new media of which the norms of pricing practices have yet to be recognized and accepted by many consumers.

2.2.2 Bundling and Prospect Theory

Bundled pricing, the selling of two or more products or services for a single price, is a quite common practice in the service industry. Hotels, for example, often offer packages that combine lodging and attraction admissions. A tour package usually comprises of transportation, lodging, meals and attraction admissions. From companies’ perspective, the use of bundling as a marketing strategy for services

makes economic sense by increasing the sales as well as profits. While a lot of the pricing bundling literature is based on economic principles, in the past two decades, considerable behavioral research has focus on consumers’ perceptions of bundles (Stremersch and Tellis, 2002). Most of the behavioral research on bundling is grounded in prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979)

Individual choices in risky situations underweight probable outcomes in

comparison with outcomes that are certain, a phenomenon labeled the certainty effect. The certainty effect brings about risk-aversion in choices involving certain gains and risk-seeking in choices involving certain losses. Winning a one-week tour of England with certainty is valued more than 50% chance to win a three-week tour of England, France, and Italy. In addition, the isolation effect indicates that individuals facing a choice among different prospects disregard components that are common to all prospects under consideration. This isolation effect will cause the framing of a prospect to change the choice that the individual decision-maker makes (Kahneman and Tversky 1979).

According to the prospect theory, decisions in risky situations are made based on values assigned to gains and losses with respect to a reference point and decision weight.

Charging customers different prices for the same product is not automatically going to create a situation of price unfairness. Rather, a lack of consideration for distributive and procedural justice as well as equity theory and the concept of dual entitlement, when setting prices may result in negative customer reaction.( Cox. 2001)

2.3 Types and Taxonomy of dynamic pricing

The related domestic Doctoral Dissertations of keywords : Internet, pricing, fairness are two articles, but they studied the Internet practices, specially on the network planning and management, they were not stress on the pricing and fairness orientation.

The following will examine the perceived fairness and the types of dynamic pricing on the Internet. The framework we examine here was initial induced from Kahneman et al (1979,1986a,1986b). Dolan and Moon (2000) suggested the market making mechanisms as Figure 1.

Market Making Mechanisms

I II III Set Price Buyer / Seller Horizontal Negotiation Interaction

Seller Seller (a) (b) (c) Auction Reverse Buying Exchange

Price Seller Sellers Buyer Buyer Bids RFP

Buyers Buyer (a) (b) (a) (b)

Periodic Dynamic Specified No Specified Price Price Starting Starting Changes Updating Point Point

Figure 1.

Three Types of Marketing Making Mechanisms

( Dolan and Moon,2000)

Kannan and Kopalle (2001) classified the dynamic Pricing on the Internet as Figure 2.

Posted Price Auction Pricing Bundle Pricing

Dynamic Dynamic Auctions Reverse Auction Exchanges Quantity Goods/ Price Pricing Name-Your-Own-Price Discounts Services Updating through ( Priceline Model ) Bundle E-Coupons

Figure 2. Taxonomy of Dynamic Pricing on the Internet

Chapter 3 Pricing Mechanisms and Methods on the Internet

Dolan and Moon (2000) discussed pricing mechanisms on the Internet. The mechanisms are of three fundamentally different types. Type I is the set price

mechanism, wherein the prices are set by the seller. Buyers are expected to “take it or leave it.” With this type of pricing, prices can be adjusted periodically, such as once every three months, or updated frequently, such as hourly or daily. Prices can also be customized for each buyer according to various rules that involve, for example, customer location, purchased history and click pattern. Type II is the negotiated price mechanism, wherein the buyer and the seller negotiate prices back and forth on the Internet. Type III is a class of mechanisms that rely on competition among buyers and sellers to produce prices. Type III consists of three subclasses – auction, reverse buying and exchange. In an auction system, the seller does not specify a price but rather provides an item, enabling buyers compete for the right to buy it in a bidding process. In a reverse buying system, the customer takes the lead in organizing the pricing process. For example, a buyer develops a Request for Proposal on an item or service, the price for which is determined in a competition involving bidding among potential sellers. In an exchange system, multiple buyers and multiple sellers come together in much the same way as at a stock exchange. Since an exchange system is rarely used in the transaction between a firm and its customers, its perceived fairness is not examined in this study.

Kannan and Kopalle (2001) derived the dynamic pricing on the Internet and studied the importance and implications for customers’ behavior. The pricing practices are more dynamic and timing, the participants involving seller and buyers of different aspects are from all-over the world, the content of the transactions are guite different

from the traditional posted-price styles. They compared the physical and virtual value chains and classified Internet dynamic pricing into three types of posted price.

Auction pricing and bundle pricing , including dynamic updating, posted price, dynamic e-coupons, auctions, priceline model, exchange, quantity discount model and bundled goods or services

From the previous papers, we probe the perceived fairness of pricing on the Internet from different pricing mechanisms and methods.

Kahneman et al ( 1986 a.b. ) used Q-methodology in studying the fairness pricing in transaction, and examined the increased market power, fair prices transaction by eighteen questions, and proposed the dual entitlement conception.

We aggregated and synthesized the pricing mechanisms and methods as five categories : increased market power, fair prices on the Internet, pricing mechanism, price discrimination and yield management.

3.1 Increased Market Power

When it was in special occurrence or shortage in market power, Kahneman (1986 a.b. ) found the increased market power as unfair. Campbell (1999 ) found the

increased market good or bad power based on motive or profit combined pricing and purchasing intention. Foley et al ( 1996 ) studied the wal-mart increased market power by pricing and competition factors.

3.2 Fair Prices on the Internet

Fairness played an important role in pricing and transactions. Campbell (1999 ) perceived unfair led to lower shopping intention. Feinberg et al ( 2000 ) examined “ What you pay will be determined by where you live or who you are “ Freg and

Pommerehne ( 1993 ) indicated a rise in price to copy with excess demand is considered unfair. Huang ( 2001 ) examined the commitment, trust, fairness and purchasing intention on unethical behaviors of web-sites, Kachelmeier et al ( 1991 ) suggested that fairness can affect market prices, but the effect decline over time, the purchase behavior not only on monetary incentives, but also consider of fairness.

Kimes ( 2002 ) discovered fair behavior is instrumental to the maximization of long-run profits. Piron and Fernandez ( 1995 ) found it was a large loss when unfairness happened. Schein ( 2001 ) probed the fairness of Isarel housing market. Tang and Xing ( 2001 ) compared the traditional retailers pricing and the Internet retailers pricing and revealed that the prices of Interent retailers are lower than the traditional retailers’ pricing.

3.3 Pricing Mechanism

Geng et al ( 2001 ) stressed the on-line auction and the auction based radically new product introductory frame work. Kauffman and Wang ( 2001 ) described the bidding and auction theory, group-buying discounts, on-line retailing and

Internet-based electronic market.

Kannan and Kopalle ( 2001 ) explained the price methods on the Internet. Kristensen ( 2000 ) found that fair price play an important role in negotiation. Maxwell et al ( 1999 ) found that with fairness and price negotiation, a seller can increase a buyer’s satisfaction without sacrificing profit. Molm et al ( 2003 ) discussed the implications for theory and for negotiation. Wang ( 1993 ) studied the auction vs posted-price selling.

The price mechanisms we examined here with perception of fairness on the Internet are : auction, group-buying discounts, price-line model and negotiation.

3.4 Price Discrimination

In Type 1 price system, the seller sets the price. All three types of discrimination discussed by economists can be applied because prices can be easily adjusted.

Practicing first-degree discrimination, a seller can offer a price based on a customer’s past purchases and mailing address, skimming as much as possible from each buyer. Firms practice second-degree discrimination by setting prices according to the quantity purchased. Practicing third-degree discrimination, a seller can offer a price based on geographical areas or on a customer’s price sensitivity. When a customer logs into q website through a price comparison site, a lower price can be posted.

Furthermore, the seller can change prices according to specified rules, such as random discounting, and discounting to new customers. Customers would consider some of these pricing practices fairer then others.

Feinberg et al ( 2000 ) pointed out the Internet was supposed to empower customers, and the pricing in Internet based on customer’s history, and personal information. Foley et al ( 1996 ) found the wal-mart adopted the different discounting in different location. Anonymous ( 1999 ) indicated that it is very easy to perform the dynamic pricing of price discrimination based on customer’s data : income level, buying habit, and customers’ address.

What we choose the survey items of price discrimination are : random, couponing discounts, geographic discrimination, discounting to new or loyal customers and discrimination based on price sensitivity.

3.5 Yield Management

Yield management, unlike any of the price discrimination methods mentioned above, involves temporal consideration in changing prices. Airlines frequently sell tickets at lower prices when reservations are made months before departures, but charge higher prices for tickets purchased one or two days ahead. On the Internet, yield management is easy to implement. The posted prices can be adjusted continually based on current demand situations and the time to receipt of service. However, customers usually do not know how the seller adjusts prices, but the may notice that prices differ each time they log into the website. Kimes ( 2002 ) found that the yield management seems to be fair.

3.6 The Framework of the Survey

From the previous traditional and dynamic Internet pricing, we propose the survey and

examination framework of this study as Figure 3.

Survey

Increased Fair Pricing Price Yield

Market Prices on Mechanism Discrimination Management Power the Internet

Auction Group- Priceline Negotiation Buying Model

Discounts

Random Couponing Discrimination Discount Geographic based on Price Discrimination Sensitivity

Discounting to New or Loyal Customers

Chapter 4 Methodology and Survey

4.1 Q-methodology

The methodology of this study is Q-methodology, (Stephenson, 1953) and Q technique is a set of procedures used to implement Q-methodology ( Kerlinger, 1992)

The Q-study of perception of behavior is very popular in social scientific and educational research.

The strength of Q-methodology (Q) is its affinity to theory. If a theory can be expressed in categories, then Q can be a powerful approach to testing theory. Q is also very suitable for intensive study of the individual, while one-way or two-way

structured sorts analysis, the study of this survey is focus on the intuition of fairness . Q can be used to test the effects of independent variables on complex dependent variables.

But Q also has its’ weakness. It’s very rare to have sufficient large samples in Q, therefore, many articles discussed the specific customer’s perception instead of the large scale examination. We used Q rank-order method, a forced-choice procedure, then how serious the violation of independence assumption, so that this study is a fairly large number and raises the requirement for statistical significance.

There are lots of studies used Q to test the perceived fairness of pricing.

Campbell (1999) used Q to test the effect of perceived unfairness including reputation and profit perception. Dickson and Kalapurakal (1994) tested the bulk electricity market by Q-methods. Oliver and Swan (1989) used Q-methodology to examine the automobile transaction perceptions. Piron and Fernandez (1995) probed the fairness and profit seeking by Q-method. Schein (2001) used Q to study the fairness

perception of pricing on Israeli housing market. Seligman and Schwartz (1997) used the same Q to compare the results with Kehneman (1986a). These authors had

examined the perception of fairness on pricing basically from the Q-methodology of Kahneman et al (1986, a.b.)

So this dissertation used the same methodology to study the framework of survey of perceived fairness of pricing specially on the Internet.

4.2 The Survey

The survey consisted of 23 questions on judgments of fairness. The methodology followed that of surveys conducted by other researchers (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Kahneman et al., 1986a). The survey presented different scenarios, which respondents were asked to rate for fairness on a five-point scale from 1 (very fair) to 5 (very unfair). Since some of the questions were similar to each other, the questions were spread across three separate questionnaires. Some questions appeared in more than one questionnaire, although the majority of the questions appeared in only one questionnaire. A respondent answered only a single questionnaire, which included from seven to ten questions.

The questions concerned the pricing of hotel rooms. Respondents were told that they were making a reservation for a hotel room on the Internet and that the hotel was located in the U.S. or in Europe.

The questionnaires were administered to MBA students in a university class in northern Taiwan. A student was randomly given one of the three questionnaires. Each student was given six extra questionnaires, which were identical to the one answered by the student. The students were asked to take the questionnaires to their coworkers or friends to collect more data. A total of 276 usable questionnaires were returned.

These 276 responses consisted of 44% males and 56% females. The majority of respondents (90%) were aged between 22 and 40. Eighty percent of the respondents had a college degree. Full time students represented 29% of the respondents.

Chapter 5 Results of The Survey

The survey results are discussed in five sub-sections, concerning increased market power, fair prices on the Internet, pricing mechanisms, price discrimination, and yield management.

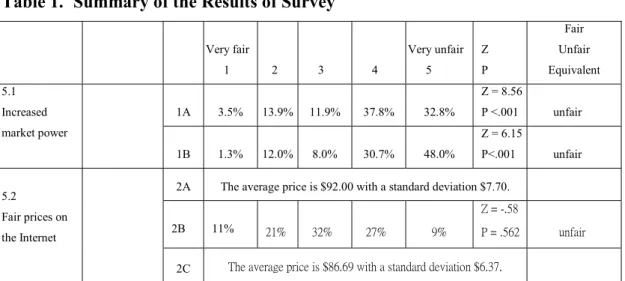

5.1 Increased market power

The following two questions about hotel pricing when market power increases were asked to facilitate a comparison with the results of previous research.

Question 1A. There are two big hotels, A and B, in a town. Hotel A is closed for renovation. The price for a room in Hotel B used to be $100 per night. However, when Hotel A is closed for renovation, Hotel B raises the price to $120. Is this price increase fair?

(N=201) Very fair 3.5% 13.9% 11.9% 37.8% 32.8% Very Unfair

About 71% (37.8% + 32.8%) of respondents (out of N=201, where N represents the number of respondents who answered the question)

considered raising prices to take advantage of the supply situation unfair. To determine whether the number of respondents who consider the price

increase is unfair is equal to those respondents who consider the price

increase fair, those in the middle are deleted and a test of the null hypotheses H0: p=0.5 is performed, where p denotes the proportion who consider the

pricing unfair out of those who consider the pricing either unfair or fair. According to our results, Z= 8.56, p < .001 for a two-tailed test. This finding

suggests that the unfairness group is significantly larger than the fairness group.

The size of the unfairness group is comparable with those of Kahneman et al. (1986a) (82%, N=107) and Frey and Pommerehne (1993) (83%, N=215). The scale used herein has a mid-point, while scales in the studies of Kahneman et al. (1986a) and Frey and Pommerehne (1993) did not have a mid-point, forcing respondents to choose either fair or unfair.

Question 1B. There are five big hotels in a town. Hotel A is closed for renovation. The price for a room in Hotel B used to be $100 per night. However, when Hotel A is closed for renovation, Hotel B raises the price to $120. The other three hotels do not raise their prices. Is this price increase fair?

(N=75) Very fair 1.3% 12.0% 8.0% 30.7% 48.0% Very Unfair Most of the respondents considered the increased market power unfair

( 78.7% vs 13.3%, Z= 6.15, P<.001). Respondents considered that Hotel B is unfair to raise prices in this scenario is equivalent as in the previous scenario (78.7% vs. 70.6%, Z = -1.34, p = .09 for a one-tailed test). The result is comparable with the finding of Frey and Pommerehne (1993). Frey and

Pommerehne (1993) found that raising the price of water is less acceptable if a second supplier exists and does not raise the price than if no second supplier exists at all. Stable prices of other products or of the same products sold by other suppliers enhance consumers’ suspicions that the supplier in question acted deliberately to treat consumers unfairly.

5.2 Fair prices on the Internet

Although no particular reasons justify differences between prices on the Internet and those in traditional channels, leading Internet retailers, such as Amazon.com, are often perceived as offering lower fixed prices than their real-world counterparts (Dolan and Moon, 2000). Lee and Gosain (2002) conducted a longitudinal price comparison of prices of music CDs in electronic and brick-and-mortar markets. They found that old-hit albums are cheaper in the Internet market, but that the prices of current-hit albums in the physical markets are comparable to those in the Internet market. Thus, consumers can be reasonably assumed to expect lower prices on the Internet than in traditional channels.

According to Prospect Theory, price expectation, or reference price, plays a crucial role in a customer’s choice processes (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). If a price is lower than expected, a consumer is likely to consider the outcome as a gain and thus fair. If a price is higher than expected, the consumer considers the outcome as a loss and thus unfair. People make choices based on perceived gain or loss, and people hate losses. Hence, reference price is an important variable for understanding perceived fairness on the part of consumers. The following three questions ask about customers’ expected prices and their perceptions of fairness on the Internet.

Question 2A. You plan to stay in a hotel. Suppose that you know that your friend has just made a reservation by fax and the price was $100. If you log into the hotel’s website and make a reservation on the Web, how much do you think the fair price should be? If you think that the fair price is higher than $100, why do you think so? If you think that the fair price is lower than $100, why do you think so? The average price is $92.00 (N = 75) with a standard deviation $7.70. Thirty-two percent of respondents answered $90, 28% answered $100, 15% answered $95 and

13% answered $80. Most respondents thought that booking on the Internet reduces the hotel’s cost, which should be passed on to consumers.

Question 2B. You plan to stay in a hotel. Suppose that you know that your friend has just made a reservation by fax and the price was $100. You know that if you make the reservation on the Web, the hotel would save manpower and thus cost, as compared with making a reservation by phone or fax. How fair is the hotel’s charging the same price on the Web as by fax or by phone?

(N=100) Very fair 11% 21% 32% 27% 9% Very Unfair No clear trend reflects such an evaluation and different and almost equal

opinions exist about price differences on the web compared to fax or phone (33% vs. 36%, Z= -.58, p = .562 for a two-tailed test).

Question 2C. You plan to stay in a hotel. Suppose that you know that your friend has just made a reservation by fax and the price was $100. Suppose that you estimate that the hotel can save $20 by having a customer make a reservation on the Web. How much do you think that the hotel should charge you to be fair?

The average price is $86.69 (N=101) with a standard deviation $6.37. Respondents expect a relatively large share of cost saving from booking on the Internet. Dual entitlement is not applicable here simply because the reference price has been lowered on the Internet.

Overall, respondents considered the same price on the Internet as in the

traditional channels to be unfair. Firms cannot keep all of the savings from operating on the Internet but should pass some on to consumers. As the results of Question 2A showed, respondents considered a saving to them of about 8% to be fair since

consumers do not usually know how much the firm is saving by accepting reservations on the Internet.

Cost saving on the Internet for hotels may be less than that for other retailers such as book retailers. Book retailers on the Internet do not need to pay overheads such as shop rental and clerks in the stores. Hotels still have all the usual running costs and administration costs as customers ordered on the Internet. Whether respondents expect different savings for different types of products on the Internet await to be explored.

5.3 Pricing Mechanism

This section examines the perceived fairness of various pricing mechanisms. Respondents considered various pricing mechanisms on the Internet to be fair,

including auction, group-buying discounts, the Priceline model and negotiation. They considered such practices to be even fairer when they enjoyed a low price than when they paid a high price.

5.3.1 Auction

A retail store, which found a Cabbage Patch doll unexpectedly, auctioned the doll to the highest bidder. This practice was considered unfair because the auction benefited the firm at the expense of the customer (Kahneman et al., 1986a). However, if the store were to declare that the proceeds from the auction were to go to UNICEF, the auction would be considered fair. Hence, the auction per se is not unfair, rather the perceived motive is being judged (Nelson, 2002). The following two questions examine the perceived fairness of an auction with an outcome that benefits either customers or the firm.

Question 3A. A resort hotel claimed that due to an economic slump its occupancy rate was very low and it had decided to auction off its rooms for a specific weekend on the Internet as a way of promoting itself. The going rate for the hotel is $100 per night. The hotel set a minimum bid price of $40. The final bid price turned out to be $70. How fair do you consider the auction of the hotel’s rooms?

Most of the respondents considered the auction fair (77.4% vs. 6.7%, Z= 7.27, p < .001 for a two-tailed test).

Question 3B. A resort hotel claimed that due to a nearby sporting event, the demand for its rooms was going to be much higher than the supply. The hotel decided to auction off on the Internet some of its rooms for the week of the event. The hotel set a minimum bid price of $100, which was the actual going rate. The final bid price turned out to be $130. Is this auction of hotel rooms fair or unfair?

(N=101) Very fair 17.8% 31.7% 28.7% 11.9% 9.9% Very Unfair About half of the respondents (49.5%) thought that the auction was fair.

Although the percentage of respondents who considered the auction to be fair in this case is significantly lower than that in the previous scenario (49.5% vs. 77.4%, Z = -3.75, p < .001 for a one-tailed test), the respondents who considered this auction to be fair outnumbered those who considered it unfair (49.5% vs. 21.8%, Z = 3.90, p<.001 for a two-tailed test). Again, the auction appears to be acceptable.

The results differ from those obtained in response to Question 1A, in which demand did not increase but customers did not have another choice. The current scenario concerns an increase in demand, not a supply shortage. Raising prices due to (N=75) Very fair 42.7% 34.7% 16.0% 2.7% 4.0% Very Unfair

general demand conditions is more acceptable than doing so because customers having no other choice (Schein, 2002).

5.3.2 Group-buying discounts

Group-buying appeals to buyers in that the final price paid is probably lower than the purchase price of the same items at other posted-price retailers. Buyers can obtain a lower price as the size of the group of buyers increases, so consumers have an incentive to recruit other consumers, reducing the retailer’s customer acquisition cost. However, a transaction can take days to complete as consumers wait for other buyers to join in the volume purchase. The time involved in completing the transaction is such that this pricing scheme may appeal only to deal-prone, price-sensitive

customers. Kauffman and Wang (2001) believed that group-buying business models lack key elements of sustainable competitive advantage. However, retailers can use this method to sell some of their units to generate interest and traffic at their websites, in the hope that consumers will remember the website and return for posted-price items. Such a pricing scheme does not guarantee that consumers enjoy prices lower than those on a posted-price website. Two scenarios are considered here – one with prices lower than the reference price, and another with a starting price that exceeds the reference price.

Question 4A. A resort hotel claimed that due to an economic slump, its occupancy rate was very low and it had decided to adopt a group-buying scheme to sell a weekend stay on the Internet. Suppose that the real actual going rate of a room is $100. The price of a hotel room will depend on the number of rooms sold. The price schedule is as follows

Number of Rooms Sold Price 0-30 $100

31-60 $80 Over 61 $65

Restated, if fewer than 30 rooms are sold, the price per room would be $100. However, if more than 31 rooms, but no more than 60 rooms are sold, the price per room would be $80. And if more than 61 rooms are sold, the price per room would be $65. Is this group-buying practice fair or unfair?

(N=100) Very fair 18% 39% 19% 19% 5% Very Unfair

Most respondents (57%) considered the group-buying discounts to be fair (57% vs. 24%, Z = 4.07, p <.001 for a two-tailed test).

Question 4B. [Same as above question]

Number of Rooms Sold Price 0-30 $110

31-60 $85 Over 61 $65

[Same as above question]

(N=75) Very fair 21.3% 32% 14.7% 26.7% 5.3% Very Unfair

Although the initial price exceeded the reference price, the respondents considered the group-buying discounts in this case to be equivalent (53.3% vs. 32%, Z = 2.16, p = .03 for a two-tailed test).

The current scenario and the scenario in Question 4A do not differ significantly (53.3% vs. 57%, Z = .48, p = .31 for a one-tailed test). Apparently, group-buying is acceptable to respondents.

5.3.3 Priceline model

In the Priceline model, when consumers know about the price and do not obtain a good deal, they are likely to be frustrated. However, when consumers are uncertain or lack the knowledge to make an informed bid, they may become conservative in their estimates and bid very low prices, increasing the percentage of unsuccessful bids and frustrating consumers. The Priceline model attracts only those customers who are knowledgeable about prices and consistently bid low to get a good deal. Thus, the margins are likely to be thin, which fact contributed to the downfall of Warehouse Club, a subsidiary of Priceline. The Priceline model was tested with two scenarios: one in which consumers obtain a price lower than the reference price, and another in which consumers must pay a higher price than the reference price. Consumers who obtain a price not higher than the reference price are expected to perceive the scheme to be fairer than those who have to pay a high price.

Question 5A. A hotel decided to adopt a pricing strategy that is similar to the Priceline model of pricing on the Internet; that is, you name a price and the hotel decides whether it would accept your offered price. If you make an offer and the hotel accepts, you cannot renege. You know a room in a similar hotel costs $100. Suppose you offer $90 for a room for one night stay and that this bid was accepted. Is this pricing method fair or unfair?

(N=75) Very fair 30.7% 46.7% 9.3% 9.3% 4% Very Unfair Most respondents considered the Priceline model to be fair when obtaining a price below the reference price (77.4% vs. 13.3%, Z = 6.12, p < .001 for a two-tailed test).

Question 5B. [Same as above] You know a room in a similar hotel costs $100. Suppose you offer $90 for a room for one night’s stay and this bid was rejected.

Hotels in the vicinity area are full, so you go back to the hotel and offer $110 for a room. Now the hotel accepts your offer. Is this pricing method fair or unfair? (N=101) Very fair 12.9% 30.7% 20.8% 21.8% 12.9% Very Unfair

Roughly the same number of respondents perceived equivalent that the method is fair as compared with those who considered it unfair (43.6% vs. 34.7%, Z =1.14, p = .25 for a two-tailed test). This is despite the fact that they must pay a higher price. When respondents obtain a price below the reference price, they tend to consider the scheme fair, as shown by the responses to Question 5A. However, when they did not enjoy a low price, the proportion of respondents who considered the scheme fair dropped sharply. The drop is statistically significant (77.4% vs. 43.6%, Z = 4.49, p < .001 for a one-tailed test).

5.3.4 Negotiation

Question 6. Suppose that you can negotiate price on the Internet, in a manner similar to negotiating for a new car. The seller gives you an asking price. You can accept or make a counter offer. The seller can accept your counter offer or make another offer. The process continues until either side quits or a price is agreed upon. You can negotiate with several vendors at the same time on the Internet. Furthermore, your offers are not binding. In other words, if a seller accepts your offer, you can still walk away with no obligation to purchase. Is this type of pricing method fair or unfair?

(N=75) Very fair 25.9% 22.4% 14.9% 24.1% 12.6% Very Unfair

Roughly the same number of respondents think that the method is fair as compared with those who think it is unfair (48.3% vs. 36.7%, Z = 1.18, p = .23 for a

two-tailed test). Intuitively, such negotiation would be considered to be very fair. That a large percentage of respondents considered the negotiation unfair is surprising. Further questioning of the respondents revealed that they considered the procedure unfair because they felt that the buyer’s backing off after negotiating a price was unfair to the firm. Apparently, buyers’ considerations of fairness extend to the seller. Buyers may feel uncomfortable if they feel that they are taking advantage of the seller.

5.4 Price Discrimination

Price discrimination involves charging different prices according to specific characteristics of customers. Random discounting, couponing, geographic

discrimination, discounting for new or loyal customers and discounting based on price sensitivity are all considered here. The results show that discounting for loyal

customers and using a pop-up window for price sensitive customers are two acceptable discounting methods.

5.4.1 Random discounting

Question 7A. When a customer logs into a hotel’s website to make a reservation, the website quotes a price selected randomly from two possible prices. For example, one customer’s price may be $105, while another customer’s price may be $95. Is this pricing method fair or unfair?

(N=98) Very fair 4.1% 8.2% 11.2% 34.7% 41.8% Very Unfair

The majority of respondents considered the pricing method unfair (76.5% vs. 12.3%, Z = 7.15, p < .001 for a two-tailed test). That Amazon.com charged their

better customers a higher price for the same DVD outraged consumers. Apparently, their explanation of random price testing was equally unacceptable.

Question 7B. [Same as above question] If the selected price is the lower one, the customer is congratulated and told that the hotel is giving randomly select customers a discount. [Same as above question]

(N=101) Very fair 5.9% 16.8% 21.8% 29.7% 25.7% Very Unfair This question is basically the same as Question 7A, except in that customers are congratulated and informed about the random discounting. The percentage of respondents who considered the pricing method fair is higher than for the preceding question (22.7% for this question, 12.3% for the preceding question, Z = 1.95, p = .025 for a one-tailed test). However, over half of the respondents still considered the pricing method unfair, and the number exceeded those who considered it fair (55.4% vs. 22.7%, Z = 4.20, p < .001 for a two-tailed test).

5.4.2 Couponing

Question 8. A hotel mails discount coupons to some of its potential customers via email, but not to others. When a customer with a coupon logs into the hotel’s website to make a reservation, the customer can enter the number on the discount coupon to obtain a discount. The customers who did not receive the discount coupon pay the full price. Hence, for example, one customer’s price may be $105, while another customer may pay $95 after the discount. Is the pricing method fair or unfair?

Coupons are not extensively used in Taiwan. About 41.3% of the respondents considered the use of coupon on the Internet fair, while about an equal number

considered it unfair (41.3% vs. 38.7%, Z = .28, p = .77 for a two-tailed test). Targeted promotions involving coupons on the Internet seem easier than in traditional channels. Consumers may feel that they can more easily obtain one in the real world by asking or searching for it if they want one. A consumer would feel frustrated and that the scheme unfair if he/she would like to use a coupon but could not obtain one anywhere on the Internet.

5.4.3 Geographic discrimination

Question 9A. Suppose you log into a hotel’s website to make a reservation for a hotel room. You are asked to indicate your location, Asia, Europe, Northern America, Southern America or Others. The hotel is quoting different prices to people from different regions. Since you are from Asia, your price is $95 (The price for people from Europe and Northern America is $105, and that for people from South America and Other regions is $95). Is this fair or unfair?

(N=99) Very fair 8.1% 19.2% 23.2% 21.2% 28.3% Very Unfair

Half of the respondents considered geographic price discrimination to be unfair even when they obtained a favorable price. This number is significantly higher than those who considered it fair (49.5% vs. 27.3%, Z = 2.87, p = .004 for a two-tailed test).

Question 9B. [Same as above] Since you are from Asia, your price is $105 (The price for people from Europe and Northern America is $95, and that for people from South America and Other regions is $105). Is this fair or unfair?

(N=75) Very fair 8.0% 14.7% 7.8% 22.7% 46.4% Very Unfair

Respondents considered charging different prices for customers who come from different geographic areas unfair (69.1% vs. 22.7%, Z = 4.37, p < .001 for a

two-tailed test). The perception of unfairness is significantly greater when the

respondents have to pay a higher price (69.1% for the current question, 49.5% for the preceding question, Z = 2.67, p = .004 for a one-tailed test).

5.4.4 Discounting to new or loyal customers

Questions 10A. Suppose you log into a hotel’s website to make a reservation for a hotel room. You find out that the hotel quotes prices according to customers’ purchasing history. Hence, for example, the price for a loyal customer is $105; while, for promotional purposes, the price for a new customer is $95. How fair do you think the hotel’s pricing is?

(N=101) Very fair 3.0% 6.9% 5.9% 28.7% 55.4% Very Unfair

Respondents perceived the situation to be the most unfair of all. A total of 84.1% of respondents consider this method to be unfair, while only 9.9% consider it to be fair (Z = 7.93, p < .001 for a two tailed test). Consumers are likely to leave such a firm to avoid being punished for their loyalty. Charging loyal customers higher prices is the essence of first-degree price discrimination. However, implementing such a scheme has very negative effects, as the Amazon.com incident indicates.

Question 10B. Suppose you log into a hotel’s website to make a reservation for a hotel room. The hotel indicates that it sets prices according to customers’

purchasing history. For example, the price for a loyal customer is $95; while the price for a new customer is $105. How fair do you think the hotel’s pricing is? (N=100) Very fair 21% 48% 13% 11% 7% Very Unfair

Giving discounts to new customers while charging loyal customers a higher price is considered to be extremely unfair. However, giving such a discount to loyal

customers is considered very fair (69% vs. 18%, Z = 5.86, p < .001 for a two-tailed test).

5.4.5 Discrimination based on price sensitivity

A firm may employ two strategies to discriminate among customers according to their price sensitivity. First, if a consumer logs into the company’s website through a price-comparison site, the consumer is more likely to be price sensitive. The firm can offer this type of consumer a lower price. Second, a consumer that logs into a

company’s website without making a reservation is more likely to be shopping around than one who makes a reservation. The firm can offer a discount to the former type of consumers using a pop-up window. This study posed the following two questions. Question 11A. Suppose you log into a hotel’s website to make a reservation for a

hotel room. You found out that when a customer visits the website directly, the price is $100. However, for a customer who uses a third-party search tool to compare prices among a number of competitors, and then connect to the hotel’s website, the price is $90. Is this fair or unfair?

The majority of respondents considered it unfair charging a lower price to those who use a price comparison site than to those who do not (80.2% vs.10.9%, Z = 7.64, p < .001 for a two-tailed test).

Question 11B. Suppose you log into a hotel’s website to reserve a hotel room. When you almost finish the reservation process, you decided that you did not want to make a reservation at that time and closed the windows that connect to the website. At this moment a new window pops up, offering you a 15% discount if you make a reservation immediately. Is this fair or unfair?

(N=74) Very fair 18.9% 35.1% 13.5% 12.2% 20.3% Very Unfair

Respondents considered it is equivalent (54.0% vs. 32.5%, Z = 2.13, p = .03 for a two-tailed test). This scenario is similar to the last one in that it seeks respondents’ perceptions of fairness of price discrimination. However, it differs from the last question in two important respects. First, in this scenario, the respondents receive the lower price, whereas in the last scenario, they did not. Second, the scenario is very similar to the bargaining situation in traditional markets. This type of market is very popular in Taiwan and people are used to bargaining. A buyer often walks away in the middle of bargaining. If the seller calls the buyer back, the buyer can return to finish the transaction. Norms plays an important role here in influencing respondents’ perception of fairness. Respondents may perceive this transaction differently in a country where bargaining is not a daily activity.

5.5 Yield Management

Yield management on the Internet involves raising or reducing prices according to market conditions. Therefore, this study posed two questions concerning price

changes; one about price increases and the other about price reductions. Following Kimes (2002), consumers are expected to complain of unfairness when they encounter price changes either upward or downward. However, consumers will perceive price increases to be less fair than price reductions.

Question 12A. You were planning to take a vacation and logged into the Internet to check prices of hotel rooms. You found a room for $100 on a hotel’s website that is acceptable. However, you did not make a reservation immediately. Two days later, you have made up your mind to reserve the room and log in to the same website. You found that the price of the hotel room has been raised to $110. How fair do you consider the price change to be?

(N=100) Very fair 6% 19% 24% 32% 19% Very Unfair

Question 12B. [Same as above] Two days later, you have made up your mind to reserve the room and log in to the same web site. You found that the price of the hotel room has been lowered to $90. How fair do you consider the price change to be?

(N=74) Very fair 18.9% 32.4% 14.9% 27.0% 6.8% Very Unfair

Only 25% of the respondents considered the price hike fair, while 51%

considered the price hike unfair (Z = 3.42, p < .001 for a two-tailed test). However, roughly half of the respondents (51.3%) considered the price reduction fair, while respondents considered it is equivalent perceived fairness (Z = 1.76, p = .07 for a two-tailed test). The difference in proportion between the two scenarios is statistically significant (25% vs. 51.3%, Z = -3.56, p < .001 for a one-tailed test). Seemingly,