TheDifference in Medical Utilization and Associated Factors between Children and AdolescentsWith and Without Autism Spectrum Disorders

Ching-MienWua,b, Pei-Tseng Kungc, Chia-Ing Lid,Wen-Chen Tsaia,*

a. Department of Healthcare Administration, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan,

R.O.C.

b. Department of Accounting, ChinaMedical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan,R.O.C. c. Department of Healthcare Administration, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C. d. Department of Medical Research, ChinaMedical University Hospital, Taichung,

Taiwan,R.O.C.

* Corresponding author: Professor Wen-Chen Tsai, Dr.PH Tel: + 886-422073070 Fax: +886-422028895

e-mail:wtsai@mail.cmu.edu.tw

Abstract

This study determined differences in health care utilization and health care expenditures

between children with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and examined possible

reasons for these differences. A retrospective longitudinal study of children agedyounger than

18 years both with and without ASD was conducted using the 2008 database of the Ministry

of the Interior registry of the disabled persons in tandem with the National Health Insurance

Research Database. Propensity score matching for the covariates of age, sex, and parental

monthly salary was used to match children at a ratio of 1:3 for observing health care

utilization among children with and without ASD from 2008 to 2011. Generalized estimating

equation analysis was performed to determine factors that affect health care utilization, such

as physician visits, emergency room (ER) visits, hospitalizations, and health care

expenditures. After matching was completed, the sample size comprised 3280 children with

ASD and 9840 children without ASD. Among the children in the sample, most were boys

(86.68%) between the ages of 6–11 years,and the average age of both samples was 9.8 years.

Afterrelevant factors were controlled for, the children with ASDyielded an average of 14.2

more annual physician visits and were more likely to visit the ER (OR = 1.12, P< .05) or be

hospitalized (OR = 1.48; P< .05) compared with the children without ASD. Compared with

expenditures (NT$26 580 more), higher ER visit expenditures (NT$50 more), higher

hospitalization expenditures (NT$5830 more), and NT$32 460 more total health care

expenditures (all P< .05). Significant predictors of health care expenditures among the

children with ASD were age, parental monthly salary, and severity of comorbidity. The most

common reasons for physician visits or hospitalizations among the children with ASD were

psychiatric illnesses, respiratory illnesses, and digestive illnesses. The children without ASD

most commonly experienced respiratory, digestive, and nervous system or sense organ

illnesses.Health care utilization among children with ASD is higher than that among children

without ASD. The results of this study can serve as a reference for governmental agencies

enacting relevant health care policies.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder (ASD); children and adolescents; health care utilization; health care expenditures

第一章 Introduction

From 2000 to 2012, the number of Taiwanese people with autism spectrum disorder

(ASD) increased by nearly 12000. The percentage of people with ASD among all people with

disabilities increased annually from 0.29% in 2000 to 1.15% in 2012,and thus,ASD is

thesecond most prevalent disability . Most people with ASD(80.62%) are children and

adolescents agedyounger than 18 years . The ratio of unmetspecific health care servicesis

higher among children and adolescents with ASD than among those with other disabilities .

Thus, the health and medical problems experienced by children and adolescents with ASD

should be addressed.

Previous research has shown that the health problems and health care utilization of

children with ASD differ from those of other children. The number of children with

ASDexhibiting limited physical functioning (including crawling, walking, and running) is 12

times that of other children . A health survey of American children aged younger than 18

years revealed that children with ASD experienced more physical and mental health

problems, including respiratory disorders and food or skin allergies, and were 9 times more

likely than other children to be depressed or anxious . Both physician and emergency room

of children with ASD in Taiwan has exhibited a significant increasing trend in recent

decades,and because of inherent inequalities in health care, they are easily overlooked by

governmental health policies. The Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program was

implemented over20 years ago, and although the national coverage rate exceeds 99.89%, few

studies on the health care utilization of children with ASD have been conducted.

Health care utilization is a form of health behavior,and research into the factors affecting

health care utilization has shown that factors other than personal health condition must be

considered. Andersen’s Behavioral Model is a comprehensiveframework of the interactions

and dynamic relationships between health behaviors and the factors affecting those behaviors

and is widely used in scientific research on health behaviors . In other words,

Andersen’sBehavioral Modelcategorizes factors influencing health care utilization as

predisposing characteristics, enabling characteristics, and need characteristics. Predisposing

characteristics are personal traits that evoke the tendencyto use health care,enabling

characteristics refer to the ability to use health care, and need characteristics refer to health

care utilization behaviors after a person perceivesthat medical treatment is necessary .

This study applied Andersen’s Behavioral Model as a basis for examining the health care

utilization behaviors of children with ASD and for analyzing the possible factors that

influence these behaviors. The results can serve as a reference for governmental agencies to

第二章

Methods Study Subjects and Source of DataThe source of data for this retrospective study was the 2008 database of the Ministry of

the Interiorregistry of the disabled persons and the NHI database of the National Health

Research Institutes. The research sample comprised children and adolescentswith and without

ASD aged from 0 to 17 years. The sample of children with ASDwas extracted from the

national database of the registry ofthe disabled persons,and the sample of children without

ASD was extracted from the NHI Database. In this sample, the records of children who were

also in the national registry of the disabled persons were excluded as well as the records of

children who sought medical treatment for ASD, as determined by physician visits coded 299

according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical

Modification (ICD-9-CM).

The participants were children with and without ASD, matched at a 1:3 ratio by using

propensity scores for the covariates of sex, age, and parental(or provider) monthly salary.

After matching was completed, differences in health care utilization (ie, physician visits, ER

visits, hospitalization admissions, and health care expenditures) were observed until the end

Measures

The dependent variables in this study were defined as health care utilization and health

care expenditures. Health care utilization modalities were physician visits, ER visits, and

hospitalization. Measured variables were mean number of annual physician visits, whether an

ER visit occurred that year, whether a child was hospitalized that year, mean number of

annual hospitalizations, and mean duration of annual hospitalizations. Furthermore, health

care expenditures includedall NHI costs,and measured variables were mean annual physician

visitexpenditures, mean annual ER visit expenditures, and mean annual hospitalization

expenditures.

The independent variables were whether a child had ASD and factors that influenced

health care utilization behaviors,which were categorized as predisposing, enabling, and need

factors according to Andersen’s Behavioral Model. The predisposing characteristics were sex,

age, and whether a child was aboriginal. Age was divided into 3 ranges: 0–5 years, 6–11

years, and 12–17 years. Information on whether a child was aboriginal was available only for

children with ASD and not for children without ASD; therefore, ethnicity was explored only

as a possible factor of health care utilization behaviors of children with ASD.

Enabling characteristics included parental (or provider’s)monthly salary and urbanization

of the residence areas. Because the participants in this study were children, the monthly

categories: NT$17 880 or less, NT$17 881–NT$22 800, NT$17 881–NT$22 800,

NT$22 801–NT$28 800, NT$28 801–NT$36 300, NT$36 301–NT$45 800, NT$45 801–

NT$57 800, NT$57 801–NT$72 800, and NT$72 801 or more. The degree of urbanization of

the residence areawas based on designations included in the study by Liu et al (2006). The

present study defined 7 degrees of urbanization, of which Level 1 represents the highest

degree and Level 7 represents the lowest. We further combined some of the designations to

form a total of4 categories: highly urbanized cities or areas designated as 1 by Liu et al;

moderately urbanized towns and developing towns or areas designated as 2 or 3; average

towns and aging towns or areas designated as 4 or 5; and agricultural towns and remote towns

or areas designated as 6 or 7.

The need characteristic assessed in this study was severity of comorbidity calculated using

the Charlsoncomorbidity index and ICD-9-CM codes . We defined 3 categories of the

Charlsoncomorbidity index scores: 0, 1, and 2 or higher.

Statistical Analysis

The participants were matched using propensity score matching. The dependent variable

was whether a child had ASD, and the independent variables were sex, age, and parental (or

provider) monthly salary. Logistic regression models were used to calculate the propensity

scores of children with and without ASD, respectively. A greedy algorithm was used for

score. If no matches were identified for a child with ASD, then a match was attempted using a

7-digit propensity score,which was reiterated to 1-digit scores. Because the sample of children

without ASD was sufficiently large, matches were unique.

Incidence and percentage were used to describe the frequency and distribution of the

variables of whether ER visits and hospitalizations occurred. Mean and standard deviation

were used to describe the independent variables related to health care utilization (ie, number

of physician visits, number of ER visits, number of hospitalizations, and duration of

hospitalization). In addition, because the data for health care expenditures yielded a skewed

distribution, all of the values related to health care expenditures were transformed

logarithmically (using log10) prior to analysis.

Because the health care utilization data of the subjects possess the characteristics of

repeated measures, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used for performing

inferential statistical analysis. GEE multiple regression or logistic regression was used

depending on the characteristics of the variable. For example, GEE multiple regression was

used forexamining the variance and associated factors in number of physician visits, number

of hospitalizations, duration of hospitalization, and health care expenditures between children

with and without ASD. GEE logistic regression was used for examining the variance and

without ASD. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary,

NC, USA) in this study.

The Statistics Center of Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, combined all datasets

with personal identification number and then provided us the datasets including the necessary

information for this study after all personal identification information has been deleted. This

study has been approved by the research ethics committee of China Medical University (IRB

No. CMU-REC-101-012).

第三章 Results

Personal Characteristics of the Study Participants and Pre- and Post-Matching Status

In 2008, the number of children with ASD was 3280, and the number of children without

ASD was 4 796 863. Before matching was conducted, age, sex, and parental (provider)

monthly salary were statistically significant (P< .05). After 1:3 matching was completed, the

sample size of children with ASD was 3280, and the sample size of children without ASD

was 9840, yielding a total sample size of 13 120. After matching was completed, no variable

achieved statistical significance (P> .05). Among the children with ASD, the number of boys

(86.68%) was higher than that of girls (13.32%),most of the children were aged between 6

and 11 years (48.64% vs 49.54%), and most had a parental monthly salary range of

Variance in Health Care Utilization Behaviors and Expenditures between Children with and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder

Table 2 indicates that physician visits, whether ER visits occurred, whether hospitalization

occurred, health care expenditures, and duration of hospitalizations were significantly higher

among children aged 0–17 years with ASDthan those among the children without ASD (P< .

05). The mean number of annual physician visits was 26.54 and 12.43, the mean number of

annual ER visits was 0.29 versus 0.25, the mean number of annual hospitalizations was 0.07

versus 0.05, and the average duration of hospitalizations was 1.46 days versus 0.21 days for

the children with and without ASD, respectively. The mean annual physician visit expenditure

was NT$33 190 and NT$6610 for the children with and withoutASD, respectively, and the

mean ER visit expenditure was NT$430 and NT$380, respectively. Furthermore, the mean

hospitalization expenditure was NT$10 310 versus NT$4480, and the mean total health care

expenditure was NT$43 930 andNT$11 470 for the children with and without ASD,

respectively (Table 2).

After sex, age, monthly salary, degree of urbanization, severity of comorbidity, and year

of observation were adjusted for, all of the health care utilization and health care expenditure

categories except for duration of hospitalization were significantly higher among the children

with ASD than those among the children without ASD. Compared with the children without

ERs 1.12 times more frequently, and were hospitalized 1.48 times more often. The physician

visit expenditures were 4.12 times higher, ER visit expenditures were 1.2 times higher,

hospitalization expenditures were 1.25 times higher, and total health care expenditures were

3.97 times higher for the children with ASDcompared withthose without ASD (all P< .05;

Table 2).

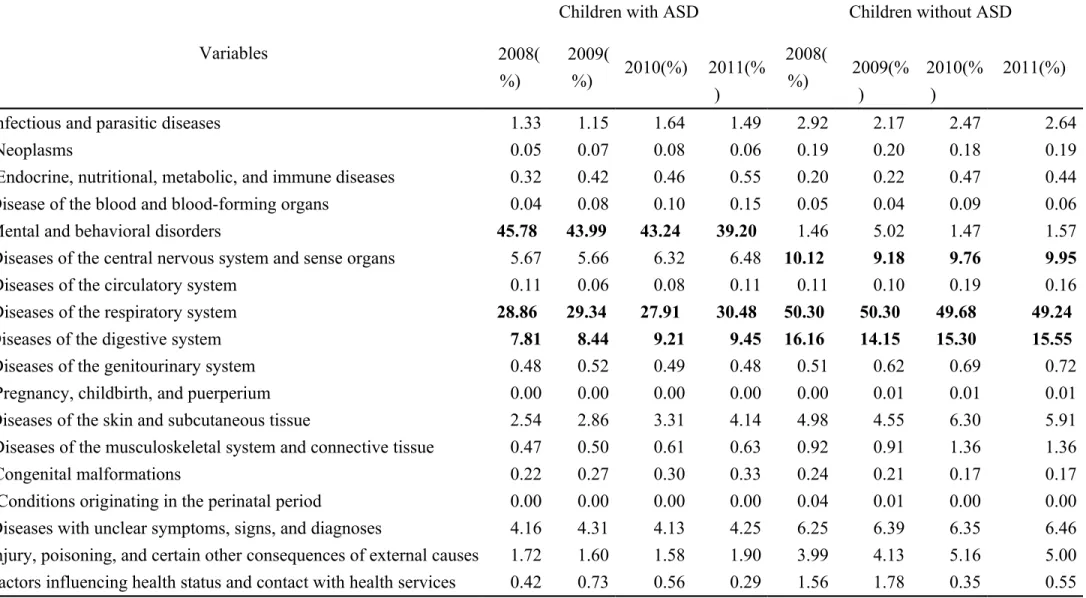

To understand the differences in medical treatment specialties sought by children with and

without ASD, we focused on the diseases and categorized these according to year. The results

showed that the children with ASD most commonly experienced psychiatric illnesses (45.8%

in 2008 and 39.2% in 2011), respiratory illnesses (28.9% in 2008 and 30.5% in 2011), and

digestive illnesses (7.8% in 2008 and 9.5% in 2011),whereas the children without ASD most

commonly experienced respiratory illnesses (50.3% in 2008 and 49.2% in 2011), digestive

illnesses (16.2% in 2008 and 15.5% in 2011), and nervous system or sense organ illnesses

(10.1% in 2008 and 10.0% in 2011; Table 3).

Factors Influencing Health Care Utilization Behaviors and Expenditures among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

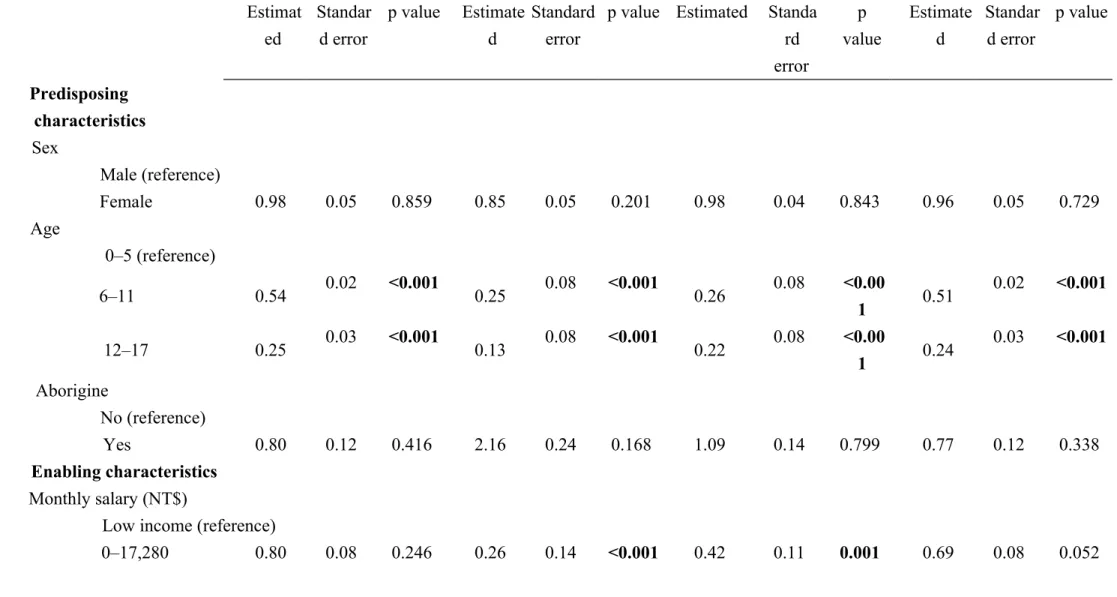

Using GEE multiple regression analysis for predictingthe independent factors of health

care behaviors of the children with ASDrevealed that the children who exhibited a

comorbidity index of 1 averaged 2.87 fewer physician visits compared with the children who

wasobserved for children who exhibited a comorbidity index of 2 or higher. Age, monthly

salary, and severity of comorbidity showed a similar predictability of whether ER visits or

hospitalizations occurred. The only factor that influenced duration of hospitalization was

ethnicity; the duration of hospitalization was 3.16 days longer for aboriginal children

compared with that for non-aboriginal children (P = .033; Table 4).

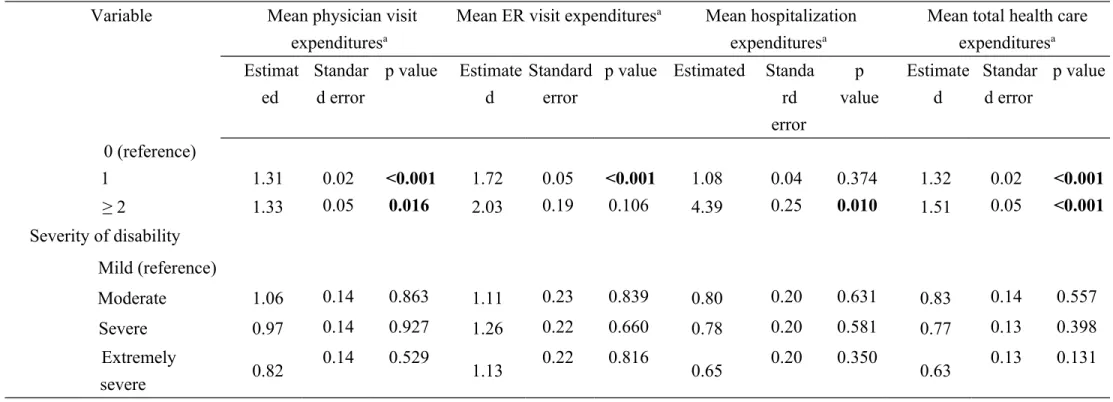

GEE multiple regression analysis for predictingindependent factors of health care

expenditures for children with ASDrevealed that age, monthly salary, and severity of

comorbidity were independent factors that could predict mean physician visit, ER visit,

hospitalization, and total health care expenditures. All expenditure categories were

significantly lower among the children aged older than 6 years with ASD than among the

children aged younger than 5 years with ASD (these values differed by factors ranging from

0.13 to 0.54, all P< .05). Compared with the children with ASD from low-income families,

the children with ASD not from low-income families had lower physician visit expenditures,

ER visit expenditures, hospitalization expenditures, and total health care expenditures (all

P< .05). Compared with the children with ASDwho exhibited lower comorbidity indices, the

children with ASDwho exhibited higher comorbidity indices had higher physician visit, ER

visit, hospitalization, and total health care expenditures (all P< .05; Table 5).

第四章 Discussion

ASD differed from those of the children without ASD, including more physician visits, ER

visits, and hospitalization. These results are consistent with those of American studies .

Studies on health care utilization based on twodatabases (1998–2004 North Dakota Medicaid

claims database and 2003–2004 Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in Southern

California) have indicated that the number of physician visits among children with ASD was

higher than that among children without ASD. In the analysis of the Medicaid claims

database, the number of annual physician visits was 79 versus 11(Croen et al, 2006; Peng et

al, 2009),and in the analysis of the nonprofit Kaiser Permanente Medical Care database the number was 89.8 versus 77.4 (Croen et al, 2006). According to a 2003–2004 survey of 85,272

American families with children aged younger than 18 years, both the number of self-reported

physician and ER visits were higher among children with ASD than that among children

without ASD (2.80 vs 1.56 for physician visits and 0.18 vs 0.10 for ER visits) . Croen et al

(2006) indicated that the percentage of children with ASD who visited the ER (10.9%) was

higher than that of children without ASD (9.8%). American studies have shown that children

with ASDwere hospitalized more often than children without ASD (5 times vs 2 times) (Peng

et al, 2009), and the duration of each hospital stay was longer (25 d vs 5 d) (Mandell et al, 2006). Although children with ASD tended to use health care services more frequently, they were 60% more likely to delay or cease treatment and were 1.14 times more likely to

suggest that health care providers must be increasingly concerned with meeting the health

care needs of children with ASD to avoid leaving the needs of these children unmet despite

frequent health care visits.

Previous studies have revealed that the health care expenditures of children with

ASDwere higher than those of children without ASD,which is consistent with our results.

American studies on Medicaid recipientshave indicated that the health care expenditures of

children with ASDwere 9 times higher than those of children without ASD, and a study of

privatelyinsured children with ASD showed that their health care expenditures were 4 to 6

times higher than those of children without ASD. Compared with these studies, we

determined a smaller variance (3.97 times, or NT$43 930 higher), which could be attributed

to the smaller variance in hospitalization costs observed in this study. Compared with the

children without ASD, the children with ASDused a higher proportion of health insurance

resources. In addition, their frequency of medical visits caused a burden on their families.

Kogan et al (2008) indicated that caring for a child with ASD is more likely to cause

economic hardship than caring for a child without ASD (39% vs 14%).

Wedetermined that children with ASDfrequently sought treatment related to psychiatric

and respiratory illnesses, and children without ASDfrequently sought treatment related to

respiratory and digestive illnesses. These findings are consistent withthe results of previous

with ASD differ from those experienced by children without ASD. Children with ASD

experience increased mental health problems ; they were9 times more likely to experience

depression or anxiety. In addition to mental health problems, children with ASD are likely to

experience respiratory illnesses and food or skin allergies . Differences in health problems

yield differences in health care utilization behaviors. Physician visits among children with

ASDtypically involve psychiatrics . The odds of using psychotropic medications were9 times

higher in children with ASD than in children without ASD,and the odds of using

gastrointestinal medications were 4 times higher in children with ASD than in children

without ASD. In addition, the reasons for hospitalization differ between children with and

without ASD. Children with ASD are more likely to be hospitalized for self-injury behaviors,

aggression toward others, depression, or obsessive-compulsive behaviors . Among children

with ASD, 13% of ER visits are for psychiatric reasons. The odds for children with ASD

visiting the ERfor psychiatric reasons were9 times higher than those for children without

ASD.

Numerous studies have shown that predisposing characteristics, such as age, sex, and

ethnicity were independent predictors of health care utilization behaviors among children with

ASD. For example, health care utilization may differ according to sex and ethnicity. Mandell

et al (2012) asserted that females with ASDwere hospitalized less often than males with ASD

insurance coverage, specialized care of autistic children differed according to ethnicity.

Nonwhite children with ASD were less likely to receive colonoscopies, fecal tests, brain

magnetic resonance imaging, and sleep assessment compared with white children . Barrett et

al (2014) analyzed the 6-month medical expenditures of 96 children with ASDbetween the

ages of 14 and 17 years and determined that each year increase in age resulted in ₤4917 less

spending and that expenditure was unrelated to sex, ethnicity, or comorbidity. Similarly, we

observed no differences in health care utilization related to sex or ethnicity, and age was the

only demographic factor that was a predictor of health care utilization. Cidav et al (2013)

asserted that as children aged, physician visits, hospitalization, and total medical expenditures

increased. Similarly, we observed that all medical expenditures increased as age increased

among the children with ASD. However, we determined that the children with ASD

agedyounger than 5 years had higher rates of hospitalization,and this rate decreased as the

children aged. This trend conforms to the British study but differs from twoAmerican studies

that have indicated that hospitalization rates increased as age increased . In addition to age, we

determined that monthly salary and comorbidity were factors affecting the total health care

expenditures of the children with ASD; however, Barrett et al (2014) indicated that

comorbidity was unrelated to medical expenditures.

Lin et al (2011) analyzed the hospitalization rate of a random sampling of children with

their study lacked an appropriate control group and could notexamine the differences in health

care utilization among children with and without ASD. In addition, theirstudy examined only

children with ASD who had been previously hospitalized and excluded those who had not

been hospitalized; therefore, the estimations of hospitalization rates and durations were

exceedingly high. We used the records of all nationally registered children with ASD in 2008,

for a total sample size of 3280 children,who were appropriately matched with children

without ASD. Their health care utilization and expenditures were calculated for a period of 4

years. Thus, this study can accurately reflect the health care utilization of children with ASD.

第五章 Conclusion

In summary, the health care utilization and expenditures of children with ASD are higher

than those of children without ASD. Children with ASD frequently seek treatment for

psychiatric illnesses, while children without ASD frequently seek treatment for respiratory

illnesses. Age, monthly salary, and severity of comorbidity are crucial predictors of health

care utilization among children with ASD. Because children with ASD cannot communicate

effectively and have mental disabilities, their cognitive and self-care abilities are inadequate.

Therefore, providing appropriate health education and preventative medical treatment to

第六章

LimitationsThis study used the secondary data to analyze. Because ofthe limitations caused bythe

fixed state of the records in the NHIRD, we could analyze only some of the variables. We

could notexamine the relationship between factors such as life style or health behavior and

health care utilization. In addition, because children earn no income of their own, we could

reference only the monthly salaries of the parents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (DMR-103-077; CMU101-ASIA-14) from China

Medical University Hospital, China Medical University, and Asia University, Taiwan.We are

grateful for the use of the National Health Insurance Research Database as provided by the

Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein

References

Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of health and social behavior, 36, 1-10.

Barrett, B., Mosweu, I., Jones, C. R., Charman, T., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Happe, F., & Byford, S. (2014). Comparing service use and costs among adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, special needs and typical development. Autism : the

international journal of research and practice.

Boulet, S. L., Boyle, C. A., & Schieve, L. A. (2009). Health care use and health and functional impact of developmental disabilities among US children, 1997-2005.

Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 163, 19-26.

Broder-Fingert, S., Shui, A., Pulcini, C. D., Kurowski, D., & Perrin, J. M. (2013). Racial and ethnic differences in subspecialty service use by children with autism. Pediatrics, 132, 94-100.

Cidav, Z., Lawer, L., Marcus, S. C., & Mandell, D. S. (2013). Age-related variation in health service use and associated expenditures among children with autism. Journal of

autism and developmental disorders, 43, 924-931.

Croen, L. A., Najjar, D. V., Ray, G. T., Lotspeich, L., & Bernal, P. (2006). A comparison of health care utilization and costs of children with and without autism spectrum disorders in a large group-model health plan. Pediatrics, 118, e1203-1211.

Deyo, R. A., Cherkin, D. C., & Ciol, M. A. (1992). Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 45, 613-619.

Fontanella, C. A. (2008). The influence of clinical, treatment, and healthcare system characteristics on psychiatric readmission of adolescents. The American journal of

orthopsychiatry, 78, 187-198.

Frazier, T. W., Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B. P., Wagner, M., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of psychotropic medication use in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder with and without caregiver-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology,

21, 571-579.

Gurney, J. G., McPheeters, M. L., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Parental report of health conditions and health care use among children with and without autism: National Survey of Children's Health. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 160, 825-830.

Kalb, L. G., Stuart, E. A., Freedman, B., Zablotsky, B., & Vasa, R. (2012). Psychiatric-related emergency department visits among children with an autism spectrum disorder.

Pediatric emergency care, 28, 1269-1276.

Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Blumberg, S. J., Singh, G. K., Perrin, J. M., & van Dyck, P. C. (2008). A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005-2006. Pediatrics,

122, e1149-1158.

Mandell, D. S., Cao, J., Ittenbach, R., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2006). Medicaid expenditures for children with autistic spectrum disorders: 1994 to 1999. Journal of autism and

developmental disorders, 36, 475-485.

Mandell, D. S., Xie, M., Morales, K. H., Lawer, L., McCarthy, M., & Marcus, S. C. (2012). The interplay of outpatient services and psychiatric hospitalization among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent

medicine, 166, 68-73.

Peng, C. Z., Hatlestad, P., Klug, M. G., Kerbeshian, J., & Burd, L. (2009). Health care costs and utilization rates for children with pervasive developmental disorders in North Dakota from 1998 to 2004: impact on Medicaid. Journal of child neurology, 24, 140-147.

Shimabukuro, T. T., Grosse, S. D., & Rice, C. (2008). Medical expenditures for children with an autism spectrum disorder in a privately insured population. Journal of autism and

developmental disorders, 38, 546-552.

Welfare, M. o. H. (2014). The Disabled Population by Classification and Grade. In NO (Ed.),

Statistical Yearbook of Social Welfare (- ed., Vol. 2014, pp. NO). Taipei: Ministry of

Health and Welfare.

Highlights:

Children with ASD had more annual physician visits, ED visits, and hospitalization. Medical expenses are 3.9 times higher inchildren with ASD than those without ASD Children with ASD oftensought treatment for psychiatric and respiratory illnesses Age, monthly salary,and comorbidity are predictors of health care expenditures.

Before matching After 1:3 matching

Variable Children with ASD Children without ASD P value Children with ASD Children without ASD p value

N % N % N % N % Total 3280 0.07 4 796 863 99.93 3280 25.00 9840 75.00 Sex <0.001 1.000 Male 2843 86.68 2 491 022 51.93 2843 86.68 8529 86.68 Female 437 13.32 2 305 841 48.07 437 13.32 1311 13.32 Age (years) 0.00 <0.001 0.493 0–5 478 14.57 1 232 610 25.70 478 14.57 1434 14.57 6–11 1625 49.54 1 654 524 34.49 1625 49.54 4756 48.33 12–17 1177 35.88 1 909 729 39.81 1177 35.88 3650 37.09 Average Age(SD) 9.41(5.04) 9.87(3.95) 9. 9.77(4.36) 9.87(3.95) Monthly Salary(NT$) <0.001 1.000

Low income household 75 2.29 89 750 1.87 75 2.29 225 2.29

0–17,280 14 0.43 449 609 9.37 14 0.43 42 0.43 17,281–22,800 816 24.88 1 645 895 34.31 816 24.88 2448 24.88 22,801–36,300 777 23.69 1 479 677 30.85 777 23.69 2331 23.69 36,301–45,800 377 11.49 429 783 8.96 377 11.49 1131 11.49 45,801–57,800 325 9.91 308 944 6.44 325 9.91 975 9.91 57,801–72,800 367 11.19 241 681 5.04 367 11.19 1101 11.19 ≧72,801 529 16.13 151 524 3.16 529 16.13 1587 16.13

Table 2Comparison of differences in health care utilization and expenditures among children with ASD and without ASD

Bivariate analysis

Multivariate generalized estimating equation models a

Children without ASD

Children with ASD

t test Children with ASD versus children

without ASD

Variable Mea

n

SD Mean SD P value Dependent variable Estimate

d 95% confidence interval P value Mean number of physician visits 12.4 3 10.0 8 26.54 2.67 <0.001 Mean number of physician visits 14.20 13.43 14. 97 <0.00 1 Mean number of ER visits 0.25 0.46 0.29 0.52 0.001 Whether ER visit occurredb 1.12 0.05 0.1 8 <0.00 1 Mean number of hospitalizations 0.05 0.21 0.07 0.23 <0.001 Whether hospitalization occurredb 1.48 0.28 0.5 1 <0.00 1 Mean duration of hospitalization in days 0.21 1.35 1.46 11.32 <0.001 Mean duration of hospitalization in days 0.10 -0.48 0.6 8 0.735

Average physician visit expenditure (NT$)c

6.61 8.18 33.19 54.36 <0.001 Average physician visit expenditure (NT$)d 4.12 3.76 4.5 1 <0.00 1 Average ER visit expenditure (NT$)c 0.38 0.82 0.43 0.92 0.007 Average ER visit expenditure (NT$)d 1.20 1.10 1.3 1 <0.00 1 Average hospitalization expenditure (NT$)c 4.48 111. 19 10.31 131.1 6 0.022 Average hospitalization expenditure (NT$)d 1.26 1.15 1.3 8 <0.00 1 Average total health care

expenditure (NT$)c 11.4 7 112. 41 43.93 143.3 9

<0.001 Average total health care expenditure (NT$)d

3.97 3.63 4.3

5

<0.00 1

aMultivariate generalized estimation equation was used to adjust for sex, age, monthly salary, degree of urbanization, severity of morbidity, and year of observation

bEstimation of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals c The unit of health care expenditures is NT$1,000

Table 3Yearly physician visits according to diseases as a percentage of total visits

Variables

Children with ASD Children without ASD

2008( %) 2009( %) 2010(%) 2011(% ) 2008( %) 2009(% ) 2010(% ) 2011(%)

Infectious and parasitic diseases 1.33 1.15 1.64 1.49 2.92 2.17 2.47 2.64

Neoplasms 0.05 0.07 0.08 0.06 0.19 0.20 0.18 0.19

Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic, and immune diseases 0.32 0.42 0.46 0.55 0.20 0.22 0.47 0.44

Disease of the blood and blood-forming organs 0.04 0.08 0.10 0.15 0.05 0.04 0.09 0.06

Mental and behavioral disorders 45.78 43.99 43.24 39.20 1.46 5.02 1.47 1.57

Diseases of the central nervous system and sense organs 5.67 5.66 6.32 6.48 10.12 9.18 9.76 9.95

Diseases of the circulatory system 0.11 0.06 0.08 0.11 0.11 0.10 0.19 0.16

Diseases of the respiratory system 28.86 29.34 27.91 30.48 50.30 50.30 49.68 49.24

Diseases of the digestive system 7.81 8.44 9.21 9.45 16.16 14.15 15.30 15.55

Diseases of the genitourinary system 0.48 0.52 0.49 0.48 0.51 0.62 0.69 0.72

Pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01

Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue 2.54 2.86 3.31 4.14 4.98 4.55 6.30 5.91

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue 0.47 0.50 0.61 0.63 0.92 0.91 1.36 1.36

Congenital malformations 0.22 0.27 0.30 0.33 0.24 0.21 0.17 0.17

Conditions originating in the perinatal period 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.04 0.01 0.00 0.00

Diseases with unclear symptoms, signs, and diagnoses 4.16 4.31 4.13 4.25 6.25 6.39 6.35 6.46 Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes 1.72 1.60 1.58 1.90 3.99 4.13 5.16 5.00 Factors influencing health status and contact with health services 0.42 0.73 0.56 0.29 1.56 1.78 0.35 0.55

Note: The 3 highest percentages per year are presented in bold

Note: The 18 classifications of illnesses are based on the international classification of diseases, injury, and death in the 1975 edition of the ICD-9

Table 4Multivariate generalized estimating equation model analysis of health care utilization behaviors in children with ASD

Variable

Average number of physician visits

Whether ER visit occurred

Whether hospitalization occurred

Average duration of hospitalization in days Estimat ed 95% C.I. p value OR 95% C.I. p

value OR 95% C.I. p value

Estimated 95% C.I. p value Predisposing characteristics Sex Male (reference) Female 10.77 -9.1 30.64 0.288 0.90 0.7 6 1.06 0.205 0.98 0.75 1.28 0.862 0.18 -3.34 3.7 0.919 Age 0–5(reference) 6–11 2.37 -0.56 5.3 0.113 0.52 0.4 4 0.61 <0.00 1 0.31 0.24 0.39 <0.001 0.08 -4.62 4.77 0.974 12–17 2.25 -1.02 5.51 0.177 0.33 0.2 7 0.39 <0.00 1 0.23 0.17 0.30 <0.001 0.3 -4.37 4.98 0.898 Aborigine No (reference) Yes 21.22 -49.3 91.74 0.555 1.52 0.9 0 2.59 0.118 1.13 0.53 2.39 0.753 3.16 0.26 6.07 0.033 Enabling characteristics Monthly

Variable

Average number of physician visits

Whether ER visit occurred

Whether hospitalization occurred

Average duration of hospitalization in days Estimat ed 95% C.I. p value OR 95% C.I. p

value OR 95% C.I. p value

Estimated

95% C.I. p value salary (NT$)

Low income (reference)

0–17,280 -4.26 -9.89 1.37 0.138 0.45 0.3 2 0.64 <0.00 1 0.34 0.19 0.62 <0.001 -0.48 -3.51 2.54 0.754 17,281– 22,800 -3.03 -8.57 2.51 0.283 0.54 0.4 1 0.71 <0.00 1 0.48 0.31 0.74 <0.001 0.87 -2.43 4.17 0.604 22,801– 36,300 -3.25 -8.43 1.93 0.219 0.45 0.3 4 0.60 <0.00 1 0.42 0.27 0.65 <0.001 -0.24 -3.04 2.56 0.865 36,301– 45,800 -2.48 -8.25 3.3 0.401 0.54 0.3 9 0.73 <0.00 1 0.54 0.33 0.88 0.013 3.04 -2.35 8.42 0.269 45,801– 57,800 -2.45 -8.25 3.35 0.408 0.53 0.3 9 0.73 <0.00 1 0.44 0.26 0.73 0.002 -2.23 -7.56 3.11 0.413 57,801– 72,800 -2.26 -8.27 3.75 0.461 0.48 0.3 5 0.65 <0.00 1 0.45 0.28 0.74 0.002 -0.49 -3.89 2.91 0.777 ≥ 72,801 -2.72 -8.18 2.74 0.329 0.51 0.3 7 0.69 <0.00 1 0.49 0.30 0.79 0.004 -0.12 -3.15 2.92 0.94

Variable

Average number of physician visits

Whether ER visit occurred

Whether hospitalization occurred

Average duration of hospitalization in days

Estimated

95% C.I. p value OR 95% C.I.

p valu e OR 95% C.I. p value Estimated 95% C.I. p value Degree of urbanization 1 (reference) 2+3 -1.84 -4.49 0.82 0.176 0.9 3 0.83 1.04 0.20 8 1.04 0.85 1.28 0.682 -2.46 -6.34 1.43 0.215 4+5 -1.65 -6.07 2.77 0.464 0.9 9 0.84 1.17 0.91 8 1.16 0.86 1.58 0.323 -1.01 -3.84 1.83 0.487 6+7 -1.79 -8.68 5.11 0.612 1.0 1 0.76 1.34 0.95 1 0.99 0.59 1.65 0.979 -2.74 -7.33 1.86 0.243 Need characteristics Severity of comorbidity 0 (reference) 1 -2.87 -5.21 -0.53 0.016 1.3 8 1.21 1.58 <.00 01 1.09 0.86 1.40 0.455 -0.95 -3.66 1.76 0.491 ≥ 2 -4.18 -10.47 2.1 0.192 1.4 2 0.93 2.16 0.10 5 3.00 1.60 5.70 0.001 -18.31 -44.5 4 7.91 0.171

Variable

Average number of physician visits

Whether ER visit occurred

Whether hospitalization occurred

Average duration of hospitalization in days

Estimated

95% C.I. p value OR 95% C.I.

p valu e OR 95% C.I. p value Estimated 95% C.I. p value Severity of disability Mild (reference) Moderate 6.81 -70.76 84.37 0.864 1.1 1 0.51 2.41 0.80 2 0.83 0.31 2.18 0.705 -0.2 -4.32 3.92 0.923 Severe -2.95 -78.59 72.7 0.939 1.2 1 0.55 2.61 0.63 9 0.76 0.30 1.99 0.582 -0.36 -3.87 3.16 0.843 Extremely severe 11.93 -63.2 87.06 0.756 1.1 3 0.52 2.44 0.76 5 0.59 0.23 1.54 0.281 -0.56 -3.71 2.59 0.727 Year under observation 2008 (reference) 2009 -1.55 -2.2 -0.9 <0.001 1.2 3 1.11 1.38 <0.0 01 1.11 0.92 1.34 0.277 0.8 0.13 1.47 0.019 2010 -4.85 -5.71 -4 <0.001 0.9 5 0.84 1.08 0.44 6 0.90 0.73 1.13 0.378 -0.55 -1.38 0.28 0.197 2011 -5.5 -7.34 -3.67 <0.001 1.0 2 0.90 1.15 0.78 8 0.84 0.67 1.06 0.154 -1.51 -2.41 -0.61 0.001

Table 5Multivariate generalized estimating equation model analysis of health care expenditures in children with ASD Variable Mean physician visit

expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value Predisposing characteristics Sex Male (reference) Female 0.98 0.05 0.859 0.85 0.05 0.201 0.98 0.04 0.843 0.96 0.05 0.729 Age 0–5 (reference) 6–11 0.54 0.02 <0.001 0.25 0.08 <0.001 0.26 0.08 <0.00 1 0.51 0.02 <0.001 12–17 0.25 0.03 <0.001 0.13 0.08 <0.001 0.22 0.08 <0.00 1 0.24 0.03 <0.001 Aborigine No (reference) Yes 0.80 0.12 0.416 2.16 0.24 0.168 1.09 0.14 0.799 0.77 0.12 0.338 Enabling characteristics Monthly salary (NT$)

Low income (reference)

Variable Mean physician visit expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value 17,281–22,800 0.77 0.07 0.119 0.34 0.12 <0.001 0.53 0.10 0.007 0.67 0.07 0.022 22,801–36,300 0.77 0.08 0.130 0.27 0.12 <0.001 0.49 0.10 0.003 0.67 0.08 0.023 36,301–45,800 0.83 0.08 0.308 0.34 0.13 <0.001 0.57 0.11 0.028 0.73 0.08 0.083 45,801–57,800 0.89 0.08 0.504 0.33 0.13 <0.001 0.49 0.11 0.005 0.78 0.08 0.184 Table 5Multivariate generalized estimating equation model analysis of health care expenditures in children with ASD (continued)

Variable Mean physician visit expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value 57,801–72,800 0.82 0.08 0.258 0.28 0.13 <0.001 0.51 0.11 0.006 0.72 0.08 0.066 ≥ 72,801 0.65 0.08 0.023 0.31 0.13 <0.001 0.54 0.11 0.014 0.59 0.08 0.005 Degree of urbanization 1 (reference) 2+3 1.03 0.02 0.634 0.90 0.04 0.211 1.00 0.03 0.947 1.03 0.02 0.607 4+5 0.98 0.04 0.860 0.98 0.06 0.904 1.12 0.05 0.311 1.03 0.04 0.702 6+7 0.99 0.06 0.908 1.00 0.10 0.995 1.01 0.08 0.946 1.03 0.06 0.829 Need characteristics Severity of comorbidity

Variable Mean physician visit expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value 0 (reference) 1 1.31 0.02 <0.001 1.72 0.05 <0.001 1.08 0.04 0.374 1.32 0.02 <0.001 ≥ 2 1.33 0.05 0.016 2.03 0.19 0.106 4.39 0.25 0.010 1.51 0.05 <0.001 Severity of disability Mild (reference) Moderate 1.06 0.14 0.863 1.11 0.23 0.839 0.80 0.20 0.631 0.83 0.14 0.557 Severe 0.97 0.14 0.927 1.26 0.22 0.660 0.78 0.20 0.581 0.77 0.13 0.398 Extremely severe 0.82 0.14 0.529 1.13 0.22 0.816 0.65 0.20 0.350 0.63 0.13 0.131

Table 5Multivariate generalized estimating equation model analysis of health care expenditures in children with ASD (continued) Variable Mean physician visit

expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value

Variable Mean physician visit expendituresa

Mean ER visit expendituresa Mean hospitalization expendituresa

Mean total health care expendituresa Estimat ed Standar d error p value Estimate d Standard error

p value Estimated Standa rd error p value Estimate d Standar d error p value 2008 (reference) 2009 1.01 0.02 0.839 1.38 0.04 <0.001 1.08 0.03 0.244 1.01 0.02 0.694 2010 0.90 0.02 0.019 0.94 0.04 0.524 0.96 0.03 0.543 0.91 0.02 0.032 2011 0.95 0.02 0.293 1.04 0.04 0.664 0.90 0.03 0.127 0.95 0.02 0.279