This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon.

Exploring the Impact of Mentoring Functions on Job Satisfaction and

Organizational Commitment of New Staff Nurses

BMC Health Services Research 2010, 10:240 doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-240 Rhay-Hung Weng (wonhon@mail2000.com.tw)

Ching-Yuan Huang (yuan@mail2000.com.tw) Wen-Chen Tsai (wtsai@mail.cmu.edu.tw)

Li-Yu Chang (jah0795@mail.jah.org.tw) Syr-En Lin (h500@stm.org.tw) Mei-Ying Lee (ming3076@sph.org.tw)

ISSN 1472-6963 Article type Research article Submission date 11 June 2009 Acceptance date 16 August 2010

Publication date 16 August 2010

Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/240

Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article was published immediately upon acceptance. It can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright

notice below).

Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central.

For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/

BMC Health Services Research

© 2010 Weng et al. , licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Exploring the impact of mentoring functions on job satisfaction and

organizational commitment of new staff nurses

1

Rhay-Hung Weng 2*Ching-Yuan Huang 3 Wen-Chen Tsai 4 Li-Yu Chang 5

Mei-Ying Lee 6 Syr-En Lin Address:

1

Hospital and Health Care Administration, Chia Nan University of Pharmacy and Science, Tainan, R.O.C. 2 International Business and Trade, Shu-Te University, Taiwan, R.O.C. 3 Health Services Administration, China Medical University, Taiwan, R.O.C. 4 Nursing, Jen-Ai Hospital, Taiwan, R.O.C 5 Nursing, Saint Paul's Hospital, Taiwan, R.O.C. 6 Nursing, St. Martin De Porres Hospital, Taiwan, R.O.C.

E-mail: 1

Rhay-Hung Weng (wonhon@mail2000.com.tw) 2

Ching-Yuan Huang (yuan@mail2000.com.tw) 3

Wen-Chen Tsai (wtsai@mail.cmu.edu.tw) 4

Li-Yu Chang (jah0795@mail.jah.org.tw) 5

Mei-Ying Lee (ming3076@sph.org.tw) 6

Syr-En Lin (h500@stm.org.tw) *

Corresponding author:

Ching-Yuan Huang

Department of International Business and Trade Shu-Te University

No. 59, Hengshan Rd., Yanchao, Kaohsiung County, 82445 Taiwan (R.O.C.) TEL: + 886-929-783601

Abstract

Background

Although previous studies proved that the implementation of mentoring program is beneficial for enhancing the nursing skills and attitudes, few researchers devoted to exploring the impact of mentoring functions on job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new nurses. In this research we aimed at examining the effects of mentoring functions on the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new nurses in Taiwan’s hospitals.

Methods

We employed self-administered questionnaires to collect research data and select new nurses from three regional hospitals as samples in Taiwan. In all, 306 nurse samples were obtained. We adopted a multiple regression analysis to test the impact of the mentoring functions.

Results

Results revealed that career development and role modeling functions have positive effects on the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new nurses; however, the psychosocial support function was incapable of providing adequate explanation for these work outcomes.

Conclusion

It is suggested in this study that nurse managers should improve the career development and role modeling functions of mentoring in order to enhance the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new nurses.

Background

Nurse turnover and turnover intent have received considerable worldwide attention

because of their influence on patient safety and health outcomes. The turnover intent

among new nurses is often higher than that among senior nurses[1]. Nurse turnover in

the first year of practice ranges between 35% and 60%[2]. With the high turnover

incidence among new nurses, it is imperative that retention strategies be effective and

that these strategies be examined closely. When new nurses perform their duties in

hospitals, they often have little or no experience in clinical nursing but they are

required to bear full responsibility of patient care. Owing to limited clinical skills,

experience, and full responsibility of patient care, new nurses would often bear heavy

work pressure. Work pressure and nurse attitudes toward jobs have significant impact

on job satisfaction and organizational commitment among hospital nurses [3-5].

Researches from various countries have confirmed that job satisfaction and

organizational commitment are statistically significant predictors of nurse

absenteeism or turnover, or their intent to quit[1, 6, 7]. Thus, in order to reduce the

nurses’ intent to leave, nurse managers should urgently address the issue of improving

the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new nurses.

Proenca and Shewchuck[8] indicate that learning and career development

nurses. Mentors play a vital role in providing these opportunities. Moreover, mentors

can facilitate professional socialization of the new nurses in nursing; facilitate their

transition into the workplace and social culture of the organization; and make them

feel welcome in peer groups, with coworkers and the organization[9]. In addition,

mentoring can promote the transfer of knowledge and values that support a hospital’s

mission. Therefore, a mentoring program is seen as a useful approach in improving

the retention of new nurses[10, 11].

The mentoring program is a formal relationship between a senior nurse and junior

nurses of a hospital directed toward the advancement and support of the junior

nurses[2, 9]. It is a useful approach for new nurses as it provides them with effective

and systematic support in the nursing practice, facilitates their professional

development, and enhances the coordination of care within the unique context of

general practice[12]. Tourigny and Pulich[13] argue that apart from the positive

influence on medical care quality, mentoring programs play an important role in

improving the work performance of the new nurses and establishing their attitudes

toward the organizations they work for. Therefore, after the implementation of the

new nurse mentoring program, mentors provide career development advice,

Psychosocial support functions include acceptance, counseling, and friendship.

Friendship is provided by informal interactions at work, and by a willingness to

discuss a variety of topics. Career development functions include sponsorship,

protection, challenging assignments, exposure, and visibility. Exposure and visibility

involve creating opportunities where important decision makers can observe and

appreciate a person’s competence, abilities, and special talents. Career development

functions focus on the organization and the mentee’s career, whereas psychosocial

support functions affect the mentee at a more personal level and extend to other areas

of life[15-17]. Besides, mentees have observed that mentors play a significant role in

shaping their views on how they would act as mentors, thus highlighting the

importance of role modeling. Role modeling is behaving and acting in a way that

others can emulate; a role model displays appropriate attitudes, values, and behaviors

to learn and follow[18-20]. In other words, role modeling functions focus on the fact

that mentees would try to imitate the mentor’s behavior because of their respect for

and trust in the mentors.

Although it has been proven in previous studies that the implementation of a

mentoring program is beneficial in terms of enhancing nursing skills and attitudes,

few researchers have explored the impact of mentoring functions on the job

paper was to examine the effects of the different mentoring functions on the work

outcomes through a survey of new nurses in Taiwan.

Methods

1 Data Source and Analysis

We employed self-administered questionnaires to collect research data. For our

subjects, we selected new nurses from three regional hospitals in Taiwan. In the

course of the study, the participating hospitals facilitated formal meetings with head

nurses, provided contact information on 308 eligible nurses who had been working in

their hospital for two years or less, and gave their full support and coordination in the

conduct of the research. We sent out 308 questionnaires over two months to survey

the new nurses anonymously.

In all, 306 nurse subjects were obtained with an overall valid response rate of 99.35%.

Because all the research data are self-reported and collected through the same

questionnaire during the same period of time, a common method variance (CMV)

may result in a systematic measurement error and may further bias the estimates of

the true relationship between the theoretical constructs[21]. We have adopted some

procedural techniques designed to address the CMV problem. These included

we also used Harman’s one-factor test to check for the presence of CMV in the data.

The Harman’s one-factor test results were as follows: twenty factors had an

eigenvalue greater than 1, and forty-four factors accounted for 97.85% of the variance.

Thus, CMV was not considered a serious threat to this study[21]. After testing for

CMV, reliability, and validity, we conducted a multiple regression analysis to test the

impact of the mentoring functions.

2 Ethical consideration

The ethical issues of this study were reviewed and approved by the ethical committee

of three sample hospitals. During the process of questionnaire collection, we also sent

out informed consent form to 308 eligible nurses to be sure that they agreed to

participate in this survey.

3 Measurement

3.1 Research Variables

Questionnaire items were designed based on existing theoretical constructs and

literature. Three mentoring experts and six nurse managers made some modifications

and the contents of the questionnaires were validated by experts. The five-point Likert

scale (1 = do not agree at all or not satisfied at all; 5 = extremely agree or extremely

the questionnaire was tested by the confirmatory factor analysis.

3.1.1 Mentoring Function: Mentoring function is defined as the sum of the career development function, psychosocial support function, and role

modeling function as perceived by nurses in the mentoring program. The

measuring scales were based on the mentoring function scales proposed by

Scandura[19], Raabe et al.[22], Sosik & Godshalk[20], and Eby et

al[23]. Nine items were prepared, including three items in three dimensions:

career development function, psychosocial support function, and role

modeling function with a Cronbach’s α value of 0.912. The mean value of

the career development function, psychosocial support function, and role

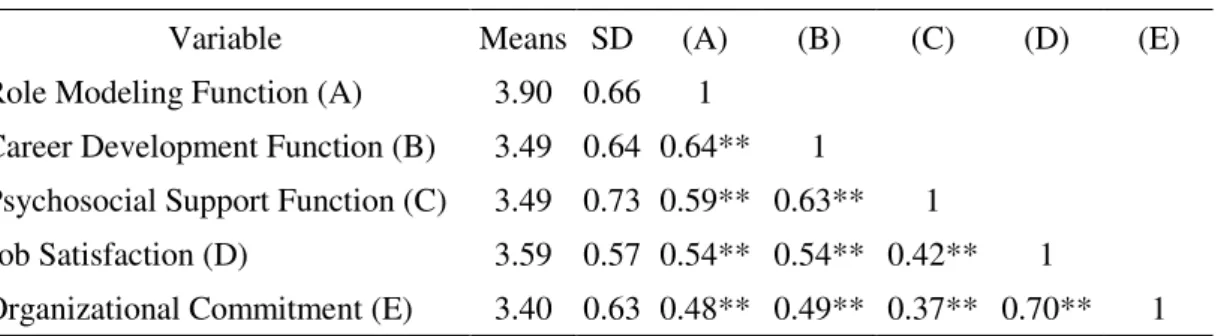

modeling function is 3.49 (SD = 0.64), 3.49 (SD = 0.73), and 3.90 (SD =

0.66), respectively.

3.1.2 Job satisfaction: After referencing literatures on job satisfaction[17, 20, 24, 25], and evaluating the nurses’ work responsibilities and experience, job

satisfaction is defined as the nurses’ overall state of satisfaction. Lankau &

Scandura[24] point out that the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire

(MSQ) is a well-constructed scale for measuring work satisfaction in the

five items with a Cronbach’s α value of 0.865 and a mean of 3.59 (SD =

0.57).

3.1.3 Organizational commitment: Organizational commitment refers to the belief in and acceptance of organizational goals and values such that nurses

are willing to make considerable efforts to achieve them, and are willing to

remain with the organization[21, 25-27]. The Organization Commitment

Questionnaire (OCQ) developed by Mowday et al.[28] is accepted as the

most widely used unidimensional measure of organizational commitment. It

contains three dimensions: value commitment, effort commitment, and

retention commitment[26]. Therefore, we developed a total of six items

with a Cronbach’s α value of 0.913 based on the OCQ and a mean of 3.40

(SD = 0.63).

3.2 Control Variables

We used sample source, mentee’s age[24, 29], mentee’s gender[24], mentee’s

education level[24], mentee’s nursing experience[24, 30], mentor’s nursing ladder[20,

30], mentoring period[24, 29], and frequency of interactions with the mentor[24, 29,

30] as control variables in our regression models. Previous literatures have

organizational commitment. Frequency of interactions with the mentor was defined as

the mentee’s perceived degree of frequency rate of interaction with mentor per month.

With respect to the measurement method, the five-point scale (1 = Seldom;

2=Sometimes;3= Normally;4= Usually;5 = Always) was used. Nursing experts

involved in the study suggested that the factors “mentor had been trained for

mentoring” and “mentor had the experience of mentoring” affect the work outcome of

the new nurses in the mentoring program. Therefore, we included these two factors as

control variables in the follow-up regression.

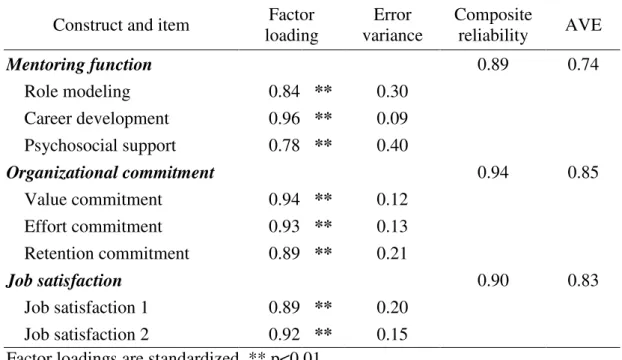

3.3 Measure Validity and Reliability

All measures were subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the AMOS

6.0 to test for unidimensionality, and convergent and discriminant validity[31]. Since

job satisfaction does not include different dimensions, this study divided the five

items of this construct into two composite indicators: the average value for the odd

number items is named “job satisfaction 1,” and the average value for the even

number items is named “job satisfaction 2.”After the CFA analysis, this model

generated acceptable fit indices (χ2/df = 2.535; GFI = 0.969; AGFI = 0.931; RMR =

0.010; CFI = 0.988; NFI = 0.981; RFI = 0.967; IFI = 0.989; TLI = 0.980; RMSEA =

0.071). Table 1 show that the minimum value of the composite reliability of all the

This indicates that every research construct possesses good internal consistency. In

addition, Table 1 shows that the factor loadings of all the research construct items

reach statistically significant levels. This indicates that the measurement model has

good convergent validity[32]. The CFA results also showed that the square roots of all

the AVE values of every research construct are higher than the pairwise correlation

coefficients; the correlation coefficients between mentoring function and

organizational commitment, between mentoring function and job satisfaction, and

between organizational commitment and job satisfaction are 0.54, 0.63, and 0.75,

respectively. This also shows that the measurement model of all the research

constructs had good discriminate validity[32].

Results

The mean age of the sample was 26.83 (SD = 3.87). Thirty-five percent of the sample

had earned a Bachelor of Science degree or higher in nursing and seventy percent of

the new nurses had nursing experience of more than one year. The mean period of the

mentoring program was 3.97 (SD = 2.43), and the frequency rate of interaction

between the mentors and mentees was 3.60 (SD = 0.86). In particular, most mentors

earned the level III of the nursing ladder or higher (69.93%), had been trained for

mentoring (62.09%), and had prior mentoring experience (83.66%) (Table 2). Besides,

During the survey period, we found that all the hospitals that were part of the study

have an existing formal program that required mentors to give guidance and

assistance to new staff nurses for at least two months. We found that the new staff

obtained clinical guidance and mentor assistance for nearly four months, during which

interaction with their mentors was frequent. Nursing managers usually assigned senior

nurses—who had achieved the level III of the nursing ladder or higher—as mentors to

guide the new staff nurses. Besides, mentors often not only had to be trained for

mentoring but also usually had to have mentoring experience. Training program for

mentoring in Taiwan is often designed for mentors. The types of this program include

classes, seminar, workshop, or conference. The topics of all types of this program are

related to the mentor’s role and responsibilities, the mentor’s communication skills,

the mentor’s clinical evaluation ability, mentor’s case teaching ability, mentor’s

teaching evaluation and feedback, medical ethics and laws, or mentor’s experience

sharing. Therefore, there were some requirements related to the mentor’s

qualifications and these not only focused on clinical expertise but also placed

importance on the mentoring abilities and experiences of senior nurses who wanted to

be mentors.

Overall, the current mentoring program for new staff nurses actually works as

the effects of the career development, psychosocial support, and role modeling

functions on them. Of these three functions, the level of the role modeling function as

perceived by the mentees is the highest (mean = 3.90) as compared with the levels of

the career development and psychosocial support functions, which are relatively

lower (mean = 3.49). Thus, the mentors who served as senior nurses actually

produced a role modeling effect on the new nurses; however, the mentees perceived

relatively limited functions that concerned the psychological and development of new

nurses (including career development and psychosocial support functions). We should

focus on this finding and view it as a critical issue that requires our efforts to improve

in the future.

Before conducting the multiple regression analysis, we adopted the Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test to examine the residual normality of the regression models. The result of

the Kolmogorov-Smirov test showed that the residual normality of each regression

model was acceptable (p > 0.05). Besides, the residual analysis plot showed that our

regression models did not violate the assumptions of linearity and homogeneity. We

also assessed the multicollinearity of the models by examining the variance inflation

factor (VIF) and found that all VIF values for independent variables were less than 7.

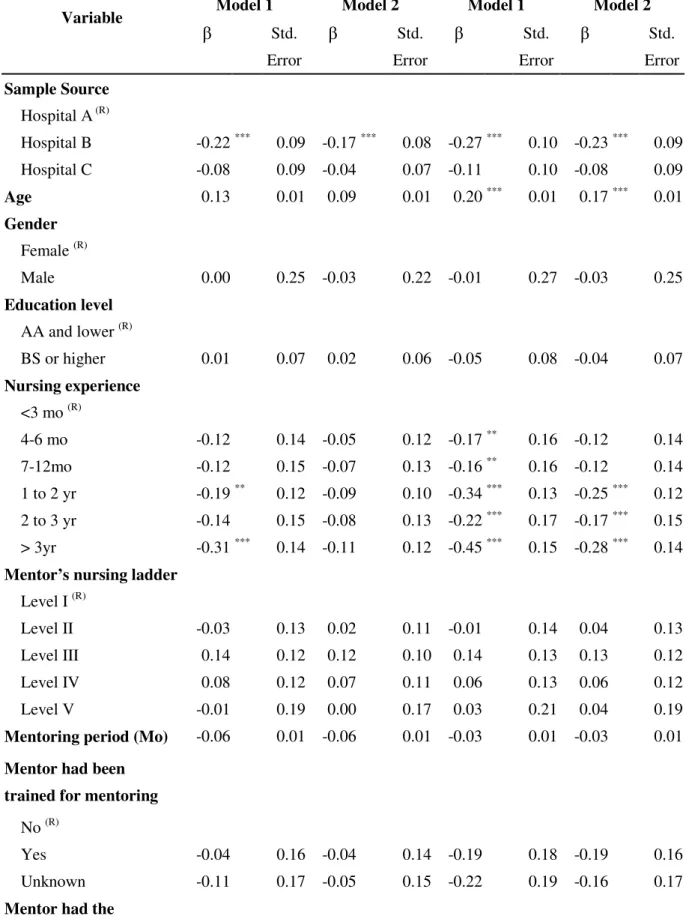

Table 4 shows the results of our multi-regression analysis for job satisfaction. The

result of Model 1 indicates that three control variables—sample source, nursing

experience, and frequency of interaction with the mentor—would significantly affect

job satisfaction. After including the variables of the mentoring functions, only the

career development function (β = 0.31) and the role modeling function (β = 0.30)

were found to be significantly and positively related to job satisfaction; however, the

coefficient of the psychosocial support function was not significant (Model 2). The

results of the regression analysis for organizational commitment showed that four

control variables—sample source, nursing experience, mentor had prior mentoring

experience, and frequency of interactions with the mentor—would have a significant

influence on organizational commitment (Model 1). After including the variables of

the mentoring functions, we also found that the impact of the career development

function (β = 0.28) and the role modeling function (β = 0.26) on organizational

commitment is significantly positive, but the coefficient of the psychosocial support

function is not significant (Model 2).

Discussion

Bahniuk[33] and Allen[34] have proven that the mentoring program enhances the job

satisfaction of the mentees. During the mentoring process, mentors would often assign

and skills, provide career guidance, support the advancement of job position, help in

resolving task-related problems, and further promote their overall growth. In this way,

mentees improve their knowledge and skills and have a clear picture about their

career development and position advancement [35-37]. The knowledge and

experience exchange and learning opportunities in the mentorship were found to

increase the mentees’ sense of confidence toward their job, decrease their anxiety for

the future, satisfy their career development needs and further create a high level of job

satisfaction [7, 19, 38]. All the above mentioned benefits for mentees primarily stem

from the career development function. Furthermore, McNeese-Smith & Nazarey[39]

had used content analysis to analyze the interview data of 30 nurses. They found that

apart from personal factors, the learning opportunities provided by the organization

are critical factors that have a highly positive relationship with organizational

commitment. In addition to providing a number of learning opportunities, mentoring

programs also provide insight into the hospital systems and regulations; create room

for performance feedbacks, discussions, and feedback friendship and offer the

necessary clinical support. These career-related functions are vital for establishing a

sense of organizational identity and organizational belonging. The organizational

commitment of mentees is positively related to their sense of organizational identity

organizational commitment that connects organizational practices and specific job

characteristics to the emotions and cognitions of employees. He found that an

individual’s perceptions of organizational support are key emotional and cognitive

processes that mobilize commitment in the workplace. Overall, study results have

proven a significant positive relationship between career development function and

job satisfaction or organizational commitment of new staff nurses.

We also found a significant positive relationship between role modeling function and

job satisfaction or organizational commitment of new nurses. As a result of the trust

and respect for the mentors, the mentees can try to imitate the mentor’s behavior in

mentorship (role modeling) and can then upgrade their expertise and skills[13, 41, 42].

Besides, the mentees’ perception of such mentoring relationships as trustful and

respectful will be beneficial for the mentees in improving their workplace experience,

perceptions, and future expectations. Therefore, if mentoring programs produced role

modeling functions, they could effectively improve the expertise and skills of new

nurses. In addition, it would facilitate the mentee’s adaptation to nursing jobs and

nursing environments. If new staff nurses adapt well to their nursing jobs and nursing

environments, they will have higher job satisfaction and few complaints against the

hospitals, invest more effort and initiative in their work, and further strengthen their

role modeling function in the mentorship, it indicates that mentors have more referent

power for mentees. In such conditions, there are fewer conflicts between mentors and

mentees when the former guide the latter. The decline in conflicts is positively related

to the growing improvement in the relationship between the mentors and mentees and

in the learning effects from the mentorship. In addition, the mentees’ commitment to

their organizations would further strengthen and improve the mentor-mentee

relationship and increase the benefits of mentoring [10, 43].

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study examined the influence of career development,

psychosocial support, and role modeling functions on the job satisfaction and

organizational commitment of new staff nurses.

The results indicated that the development of mentoring programs for new staff nurses

in Taiwan has reached a mature state and that the interactions between new nurses and

their mentors are frequent, useful, and enduring. To serve as mentors, nurse managers

assigned senior nurses who had been trained for mentoring, had previous mentoring

experience, and had at least achieved the level III of the nursing ladder. In addition,

mentoring programs for new nurses are indeed capable of generating the role

that mentors do exhibit a higher degree of nursing knowledge and technical

capabilities; thus, the role modeling function appears to be significant in the

mentoring process. However, it is likely that nursing mentors are not concerned about

the psychosocial needs (for example, high praise from their mentors and the

establishment of friendship in the workplace) and career anxieties or directions of new

nurses. Therefore, the psychosocial support and career development functions, as

perceived by new nurses, appear to be lower in Taiwan. Despite being perceived to be

relatively lower by the new nurses, these two functions positively influence their job

satisfaction and organizational commitment. If nurse managers want to improve the

mentoring programs for new staff nurses, they should encourage mentors towards the

direction of lending psychosocial support, providing directions on career development,

giving opportunities for self-expression and promotion, and assigning challenging

tasks that provide more learning opportunities for the new nurses. Effective mentoring

will reinforce the job satisfaction of the new nurses and their commitment to the

hospital.

In addition, the results of this study show that the role modeling function provided by

mentors will positively influence the job satisfaction and organizational commitment

of new staff nurses. If the nursing mentors can exhibit a high degree of nursing

benchmarks, it will facilitate the mentee’s adaptation to their jobs and workplaces and

will further enhance their job satisfaction and improve their organizational

commitment. Therefore, while selecting senior nurses as mentors for new nurses,

nurse managers should carefully consider their expertise and abilities. Besides

expertise and abilities, nursing managers should reinforce the mentor’s professional

attitudes about nursing care and assist in improving their mentoring abilities in order

to strengthen the role modeling functions of the mentoring programs.

Limitations and future research suggestions

Since this study has a cross-sectional design, it has certain empirical limitations with

regard to the verification of the relationship between research constructs. Therefore, it

is suggested that future researchers use a study with a longitudinal design to further

consider the impact of mentoring functions on job satisfaction and organizational

commitment. In addition, we used Harman’s one-factor test to assess the seriousness

of common method biases. Although test results indicated that CMV was not

considered a serious threat to this study, we suggest that if future researchers can

overcome the data-collection and time-limitation problems, they can try to use the

temporal, proximal, psychological, or methodological separation of measurement to

Furthermore, this study only surveyed new staff nurses of Taiwan’s hospitals;

therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to other countries. Future researchers

may collect samples from different countries and continue to test the assumptions of

this research. Finally, future researchers can continue to investigate from different

perspectives in order to explore the influential factors and the impact of these factors

on the different dimensions of work outcomes (such as patient safety performance)

and further strengthen the integrity of the theory of mentorship in nursing.

Competing Interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

WRH conceived of the study and made substantial contributions to study design, data

acquisition, and data analysis and result interpretation. He also took responsibility for

drafting and revising the manuscript. HJY performed the statistical analysis, assisted

in interpreting the results and writing the manuscript. TWC was involved in designing

the study, interpreting the analysis results and providing many important directions for

literature review and discussion. CLY, LMY, and LSE took responsibility for data

collection, participated in the data analysis and contributed to discussions. All authors

Appendix.1 Construct Measurement Items Mentoring Function

Career development

The mentor gave me many important assignments that provided me with

opportunities to learn nursing skills, for example, case analysis.

The mentor provided me with many suggestions about career development and

highlighted the relevant concerns.

The mentor gave me a lot of information about position advancement

opportunities.

Psychosocial support

I would discuss my private concerns and problems with my mentor.

I actually see my mentor as my “real” friend.

After work, I still kept in touch with my mentor.

Role modeling function

I tried to adapt my mentor’s behavior.

I really respect and admire my mentor’s nursing expertise and skills.

I really respect and admire my mentor for her mentoring expertise and skills.

Job Satisfaction

With regard to the sense of achievement while finishing my jobs, I feel…….

With regard to the performance feedbacks, I feel…….

With regard to whether my salary and welfare are commensurate with the

workload, I feel…….

With regard to the interactions with my coworkers, I feel…….

Organizational Commitment

Effort commitment

I am willing to put in extra efforts for my hospital.

I am willing to make an all-out effort to keep up with the hospital’s development.

Value commitment

I feel a sense of pride in doing my job at this hospital.

My current work environment is the ideal one, which I always hoped to work in.

Retention commitment

Even though there are better opportunities outside, I will not leave this hospital.

I have strong commitment to continue providing my services at this hospital until

retirement.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council in Taiwan

References

1. Beecroft PC, Dorey F, Wenten M: Turnover intention in new graduate

nurses: A multivariate analysis. J Adv Nurs 2008, 62:41-52.

2. Halfer D, Graf E, Sullivan C: The organizational impact of a new graduate

pediatric nurse mentoring program. Nurs Econ 2008, 26:243-249.

3. Lu H, While AE, Barriball KL: Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature

review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2005, 42:211-227.

4. Chu CI, Hsu HM, Price JL: Job satisfaction of hospital nurses: An

empirical test of a causal model in Taiwan. Int Nurs Rev 2003, 50:176-182.

5. Brief AP, Aldag RJ: Antecedents of organizational commitment among

hospital nurses. Work and Occupations 1980, 7:210-221.

6. Lee TY, Tzeng WC, Lin CH, Yeh ML: Effects of a preceptorship

programme on turnover rate, cost, quality and professional development.

J Clin Nurs 2009, 18:1217-1225.

7. Salt J, Cummings G, Profetto-McGrath J: Increasing retention of new

graduate nurses: A systematic review of interventions by healthcare organizations. J Nurs Adm 2008, 38:287-296.

8. Proenca EJ, Shewchuck: Organizational tenure and the perceived

importance of retention factors in nursing homes. Health Care Manag Rev

1997, 22:65-73.

9. Beecroft PC, Santner S, Lacy ML, Kunzman L, Dorey F: New graduate

nurses' perceptions of mentoring: Six-year programme evaluation. J Adv

Nurs 2006, 55:736 -747.

10. Andrews M, Wallis M: Mentorship in nursing: A literature review. J Adv Nurs 1999, 29:201-207.

11. Greene MT, Puetzer M: The value of mentoring: A strategic approach to

retention and recruitment. J Nurs Care Qual 2002, 17:63-70.

12. Gibson T, Heartfield M: Mentoring for nurses in general practice: An

Australian study. J Interprof Care 2005, 19:50-62.

13. Tourigny L, Pulich M: A critical examination of formal and informal

14. McCloughen A, O'Brien L: Development of a mentorship programme for

new graduate nurses in mental health. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2005, 14:276-284.

15. Ragins BR, Cotton J: Mentor functions and outcomes: A comparison of

men and women in formal and informal mentoring relationships. J Appl

Psychol 1999, 84:529-550.

16. Scandura TA: Mentorship and career mobility: An empirical investigation. J Org Behav 1992, 13:169-174.

17. Scandura TA: Mentoring and organizational justice: An empirical

investigation. J Vocat Behav 1997, 51:58-69.

18. Kram KE: Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in

organizational life. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman; 1985.

19. Scandura TA, Williams EA: An Investigation of the moderating effects of

gender on the relationships between mentorship initiation and protégé perceptions of mentoring functions. J Vocat Behav 2001, 59:342-363.

20. Sosik JJ, Godshalk VM: Leadership styles, mentoring functions received,

and job-related stress: A conceptual model and preliminary study. J Org

Behav 2000, 21:365-390.

21. Podsakoff P, Organ D: Self-reports in organizational research: Problems

and prospects. J Manag 1986, 12:531-544.

22. Raabe B, Beehr TA: Formal mentoring versus supervisor and coworker

relationships: Differences in perceptions and impact. J Org Behav 2003, 24:271-293.

23. Eby LT, Lockwood AL, Butts M: Perceived support for mentoring: A

multiple perspectives approach. J Vocat Behav 2006, 68:267-291.

24. Lankau MJ, Scandura TA: An investigation of personal learning in

mentoring relationships: content, antecedents, and consequences. Acad

Manag J 2002, 45:779-790.

25. Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J: The impact of workplace

empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses' work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Manag Rev 2001, 26:7-23.

organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev 1991, 1:61-89.

27. Payne SC, Huffman AH: A longitudinal examination of the influence of

mentoring on organizational commitment and turnover. Acad Manag J

2005, 48:158-168.

28. Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW: The measurement of organizational

commitment. J Vocat Behav 1979, 14:224-247.

29. Godshalk VM, Sosik JJ: Aiming for career success: The role of learning

goal orientation in mentoring relationships. J Vocat Behav 2003, 63:417-437.

30. Day R, Allen TD: The relationship between career motivation and

self-efficacy with protégé career success. J Vocat Behav 2004, 64:72-91.

31. Bollen KA: Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989.

32. Fornell C, Larcker DF: Evaluating structural equation models with

unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 1981, 48:39-50.

33. Bahniuk MH, Dobos J, Kogler Hill SE: The impact of mentoring, collegial

support, and information adequacy on career success: A replication. J Soc

Behav Pers 1990, 5:431-451.

34. Allen TD, Russell JEA, Maetzke SB: Formal peer mentoring: Factors

related to protégés satisfaction and willingness to mentor others. Group

Organization Manag 1997, 22:488-507.

35. Fawcett DL: Mentoring--what it is and how to make it work. Association of Operating Room Nurses 2002, 75:950-954.

36. Gibson T, Heartfield M: Mentoring for nurses in general practice: An

Australian study. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2005, 19:50-62.

37. Tourigny L, Pulich M: A critical examination of formal and informal

mentoring among nurses. The Health Care Manager 2005, 24:68-76.

38. Underhill CM: The effectiveness of mentoring programs in corporate

settings: A meta-analytical review of the literature. J Vocat Behav 2006, 68:292-307.

organizational commitment among nurses / practitioner application. J

Healthc Manag 2001, 46:173-187.

40. Fang SR: An emperical study on relationship value, relationship quality

and loyalty for retailing bank industry. J Manag 2002, 19:1097-1130.

41. Scandura TA, Williams EA: Mentoring and transformational leadership:

The role of supervisory career mentoring. J Vocat Behav 2004, 65:448-468.

42. Wanberg CR, Welsh ET, Hezlett SA: Mentoring research : A review and

dynamic process model. Hum Resour Manag 2003, 22:39-124.

43. Donaldson SI, Ensher EA, Grant-Vallone EJ: Longitudinal examination of

mentoring relationships on organizational commitment and citizenship behavior. J Career Development 2000, 26:233-249.

Tables

Table 1 Assessment of Convergent and Discriminant Validity (n=306) Construct and item Factor

loading Error variance Composite reliability AVE Mentoring function 0.89 0.74 Role modeling 0.84 ** 0.30 Career development 0.96 ** 0.09 Psychosocial support 0.78 ** 0.40 Organizational commitment 0.94 0.85 Value commitment 0.94 ** 0.12 Effort commitment 0.93 ** 0.13 Retention commitment 0.89 ** 0.21 Job satisfaction 0.90 0.83 Job satisfaction 1 0.89 ** 0.20 Job satisfaction 2 0.92 ** 0.15 Factor loadings are standardized. ** p<0.01.

Table 2 Frequencies and Percentages on Selected Respondent Characteristics (n=306)

Variable Frequency % Variable Frequency %

Sample Source Mentor’s nursing ladder

Hospital A 81 26.47 Level I 31 10.13

Hospital B 108 35.29 Level II 61 19.93

Hospital C 117 38.24 Level III 119 38.89

Sex Level IV 83 27.12

Female 301 98.37 Level V 12 3.92

Male 5 1.63 Mentor had been trained for

mentoring

Education level No 14 4.58

AA and lower 199 65.03 Yes 190 62.09

BS or higher 107 34.97 Unknown 102 33.33

Nursing experience Mentor had the experience

of mentoring <3 mo 32 10.46 No 13 4.25 4-6 mo 31 10.13 Yes 256 83.66 7-12mo 27 8.82 Unknown 37 12.09 1 to 2 yr 94 30.72 2 to 3 yr 24 7.84 > 3yr 98 32.03

Table 3 Means, Standard Deviation and Correlation Matrix for Research Constructs

Variable Means SD (A) (B) (C) (D) (E)

Role Modeling Function (A) 3.90 0.66 1

Career Development Function (B) 3.49 0.64 0.64** 1

Psychosocial Support Function (C) 3.49 0.73 0.59** 0.63** 1

Job Satisfaction (D) 3.59 0.57 0.54** 0.54** 0.42** 1

Organizational Commitment (E) 3.40 0.63 0.48** 0.49** 0.37** 0.70** 1 ** p < .05

Table 4 Results of multiple regression analysis a (n=306)

Job Satisfaction Organizational Commitment

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2

Variable β Std. Error β Std. Error β Std. Error β Std. Error Sample Source Hospital A (R) Hospital B -0.22 *** 0.09 -0.17 *** 0.08 -0.27 *** 0.10 -0.23 *** 0.09 Hospital C -0.08 0.09 -0.04 0.07 -0.11 0.10 -0.08 0.09 Age 0.13 0.01 0.09 0.01 0.20 *** 0.01 0.17 *** 0.01 Gender Female (R) Male 0.00 0.25 -0.03 0.22 -0.01 0.27 -0.03 0.25 Education level AA and lower (R) BS or higher 0.01 0.07 0.02 0.06 -0.05 0.08 -0.04 0.07 Nursing experience <3 mo (R) 4-6 mo -0.12 0.14 -0.05 0.12 -0.17 ** 0.16 -0.12 0.14 7-12mo -0.12 0.15 -0.07 0.13 -0.16 ** 0.16 -0.12 0.14 1 to 2 yr -0.19 ** 0.12 -0.09 0.10 -0.34 *** 0.13 -0.25 *** 0.12 2 to 3 yr -0.14 0.15 -0.08 0.13 -0.22 *** 0.17 -0.17 *** 0.15 > 3yr -0.31 *** 0.14 -0.11 0.12 -0.45 *** 0.15 -0.28 *** 0.14

Mentor’s nursing ladder

Level I (R)

Level II -0.03 0.13 0.02 0.11 -0.01 0.14 0.04 0.13

Level III 0.14 0.12 0.12 0.10 0.14 0.13 0.13 0.12

Level IV 0.08 0.12 0.07 0.11 0.06 0.13 0.06 0.12

Level V -0.01 0.19 0.00 0.17 0.03 0.21 0.04 0.19

Mentoring period (Mo) -0.06 0.01 -0.06 0.01 -0.03 0.01 -0.03 0.01

Mentor had been trained for mentoring

No (R)

Yes -0.04 0.16 -0.04 0.14 -0.19 0.18 -0.19 0.16

Unknown -0.11 0.17 -0.05 0.15 -0.22 0.19 -0.16 0.17

Mentor had the

No (R)

Yes 0.11 0.17 -0.02 0.15 0.25 ** 0.19 0.14 0.17

Unknown 0.10 0.19 0.02 0.17 0.24 ** 0.21 0.18 0.19

Frequency of interacting

with the mentor 0.23

*** 0.04 -0.02 0.04 0.21 *** 0.04 0.00 0.04 Mentoring function Role modeling 0.31 *** 0.06 0.26 *** 0.07 Career development 0.30 *** 0.06 0.28 *** 0.07 Psychosocial support 0.05 0.05 0.03 0.06 R2 0.15 0.39 0.18 0.36 Adj.R2 0.09 0.34 0.12 0.30 F Change 2.47 *** 36.81 *** 3.13 *** 25.55 *** a

Standardized regression coefficients are shown in the table ** p < .05;*** p <.01; (R) reference group