CHAPTER FOUR DISCUSSION

This chapter will further explore the results presented earlier. Section 4.1 probes into the learning styles and multiple intelligences dominating the subjects’

English proficiency. Moreover, Sections 4.2 and 4.3 discuss the differences in learning styles and multiple intelligences between the high achievers and the low achievers. Section 4.4 examines the relationship between the subjects’ English proficiency and their background variables. Finally, Section 4.5 presents a summary of the main points of this chapter.

4.1 Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences Dominating EFL Students’

English Proficiency

In this section, Multiple Regression was performed to investigate the relationship between the subjects’ English proficiency and their learning styles/

multiple intelligences. Results with regard to learning styles and multiple intelligences dominating the subjects’ English proficiency are presented.

4.1.1 Learning Styles v.s. English proficiency

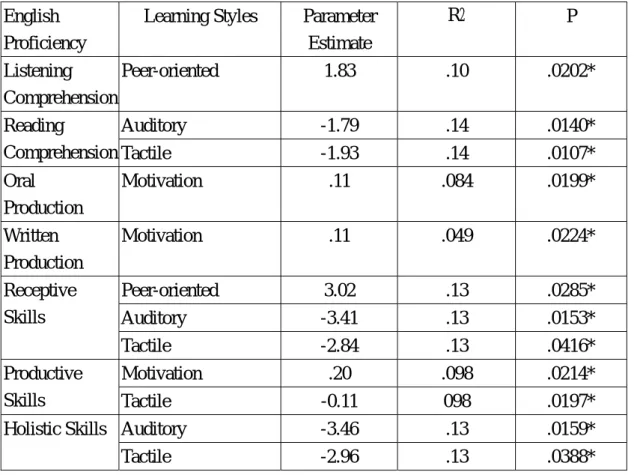

As can be seen in Table 4-1, of all the learning styles, only four were correlated with their English proficiency: peer-oriented, auditory, motivation, and tactile learning:

Table 4-1 Subjects’ Learning Styles v.s. their English Proficiency English

Proficiency

Learning Styles Parameter Estimate

R2 P

Listening Comprehension

Peer-oriented 1.83 .10 .0202*

Auditory -1.79 .14 .0140*

Reading

Comprehension Tactile -1.93 .14 .0107*

Oral Production

Motivation .11 .084 .0199*

Written Production

Motivation .11 .049 .0224*

Peer-oriented 3.02 .13 .0285*

Auditory -3.41 .13 .0153*

Receptive Skills

Tactile -2.84 .13 .0416*

Motivation .20 .098 .0214*

Productive

Skills Tactile -0.11 098 .0197*

Auditory -3.46 .13 .0159*

Holistic Skills

Tactile -2.96 .13 .0388*

Notes: R2 stands for R-square.

*indicates statistically significant difference at p< .05.

It was found that peer-oriented learning was positively correlated with their listening comprehension (R2= .10, p< .05) and receptive skills (R2= .13, p< .05).

Since listening comprehension involves discussion and communication with others, it is understandable why the peer-oriented learners seemed to perform better in the listening comprehension parts. Auditory learning was negatively correlated with the subjects’ reading comprehension (R2= .14, p< .05), receptive skills (R2= .13, p< .05), and holistic skills (R2= .13, p< .05). The result is inconsistent with Tsao’s (2003) and Park’s (1997) findings that the high achievers showed a significantly positive preference for auditory learning. This may be related to the contents of the learning style questionnaire. More specifically, most of the statements regarding the category

of auditory learning involved expressions concerning “ discussion with others”, but generally high achievers were considered more capable of learning on their own.

Many researchers have also found that high achievers preferred individual learning while low achievers preferred group learning (c.f. Park, 1997; Tsao, 2002).

Therefore, such statements were likely to make the low achievers who preferred learning through discussion respond positively to this category. This explains why our low achievers seemed to have a higher preference for auditory learning.

In addition, motivation was positively correlated with the subjects’ oral (R2= .084, p< .01), and written production (R2= .11, p< .05), and productive skills (R2= .20, p< .05). The finding is in agreement with Cheng (1993), who found that there was a strong association between the students’ motivational intensity and their EFL achievement and Peng (2002), who concluded that learners’ motivational intensity had significant and positive correlation with achievement. In our study, the students’

productive skills were measured by their performances in an oral test and writing task, which required their preparation beforehand. Therefore, the subjects with stronger motivation were more likely to obtain good scores. Besides, tactile learning was found to be negatively correlated with their reading comprehension (R2= .14, p< .05), receptive (R2= .13, p< .05), and productive skills (R2= .098, p< .05), and holistic skills (R2= .13, p< .05). This result was similar to Chang’s (1998) finding that English proficiency1 was correlated with hands-on (tactile) learning styles. In general, tactile learners learn best through hands-on activities or verifying what they have learned.

However, students hardly can use English in their daily lives for it is a foreign language.

Consequently, such EFL environment might be disadvantageous to the tactile learners and contributed to their poor performance in English proficiency.

Finally, it is noticeable that the students’ English proficiency generally had little

1 The English proficiency was determined by the total scores of TOEFL.

to do with their learning styles ( R2≦ .14).

4.1.2 Multiple intelligences v.s. EFL proficiency

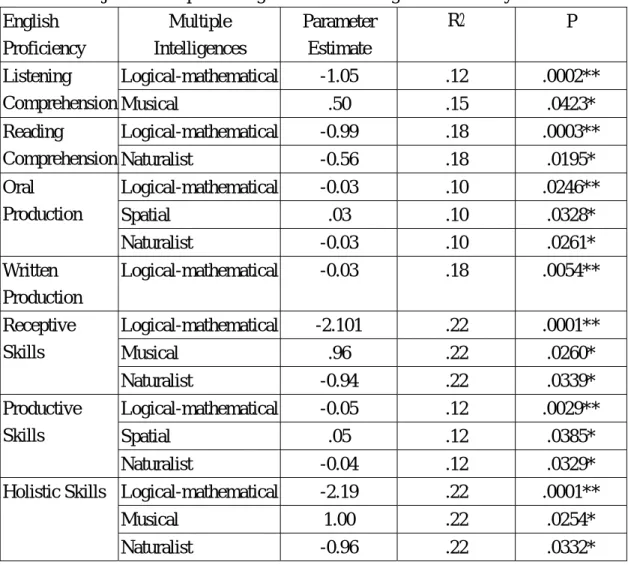

The influence of multiple intelligences on the subjects’ English proficiency is shown in Table 4-2:

Table 4-2 Subjects’ Multiple Intelligences v.s their English Proficiency English

Proficiency

Multiple Intelligences

Parameter Estimate

R2 P

Logical-mathematical -1.05 .12 .0002**

Listening

Comprehension Musical .50 .15 .0423*

Logical-mathematical -0.99 .18 .0003**

Reading

Comprehension Naturalist -0.56 .18 .0195*

Logical-mathematical -0.03 .10 .0246**

Spatial .03 .10 .0328*

Oral Production

Naturalist -0.03 .10 .0261*

Written Production

Logical-mathematical -0.03 .18 .0054**

Logical-mathematical -2.101 .22 .0001**

Musical .96 .22 .0260*

Receptive Skills

Naturalist -0.94 .22 .0339*

Logical-mathematical -0.05 .12 .0029**

Spatial .05 .12 .0385*

Productive Skills

Naturalist -0.04 .12 .0329*

Logical-mathematical -2.19 .22 .0001**

Musical 1.00 .22 .0254*

Holistic Skills

Naturalist -0.96 .22 .0332*

Notes: R2 stands for R-square.

* indicates statistically significant difference at p< .05.

** indicates statistically significant difference at p< .01.

The result showed that of the eight intelligences, four were correlated with the students’ English proficiency: logical-mathematical, naturalist, musical, and spatial intelligences. It is interesting to find that logical-mathematical intelligence was

negatively correlated with the subjects’ English proficiency in every skill (p< .01 ).

Similarly, there was a significantly negative correlation between the subjects’

naturalist intelligences and English proficiency (p< .05 ) except for their listening comprehension and written production. Such result seemed to support the common notion that students who do well in science usually obtain poor grades in recitation work. On the other hand, the subjects’ musical intelligences were positively correlated with their listening comprehension (R2=.12, p< .05 ), receptive skills (R2

=.22, p< .05 ), and holistic skills (R2= .22, p< .05 ). This finding is consistent with the common notion that musical intelligence is crucial to competence of perceiving and producing the intonation patterns of a second language (Brown, 1994). Finally, the subjects’ spatial intelligences were positively correlated with their oral production (R2= .10, p< .05 ) and productive skills (R2= .12, p< .05 ). One possible reason is that speaking skills sometimes involve sense of direction, concrete feelings to one’s surroundings, etc. Hence, it may assist an L2 learner in growing comfortable in new surroundings, as Brown (1994) suggests.

On the whole, the correlation between the subjects’ logical-mathematical intelligences and English proficiency was significantly highest (p< .01). Besides, the correlation between the subjects’ English proficiency and their multiple intelligences was found to be negligible ( R2≦ .22).

4.2 Differences in Learning Styles between the High and Low-Achievers

To further examine if there were significant differences in learning styles between the high and low-achievers, a series of t-tests were performed. Besides, interviews2 were conducted to confirm the t-test results and find out why the subjects

2 Six subjects were selected for the interview. Those who were scored high in the four tests (i.e.,

preferred a certain learning style. The t-tests as well as the major interview results are presented and discussed in this section.

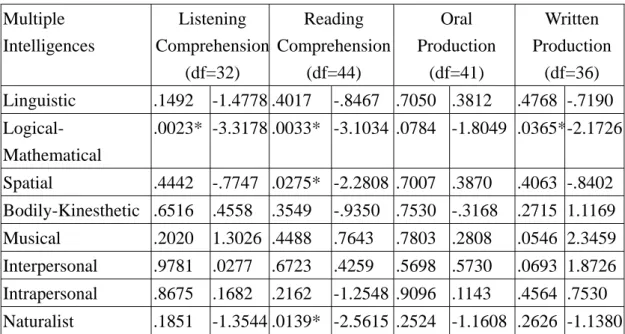

Different from the findings of Park (2000) and Cheng (1997), the t-test results as listed in Tables 4-3 & 4-4 show that there were significant differences in motivation, auditory learning, and tactile learning between the high and low achievers:

Table 4-3 T-tests for Differences in Learning Styles between the High and Low-Achievers in the Four Skills

Styles Listening Comprehension

(df=32)

Reading Comprehension

(df=44)

Oral Production

(df=41)

Written Production

(df=36) Motivation .4795 .7154 .5064 .6700 .3404 .9646 .0031* 3.1756 Persistence .7684 -.2969 .4621 -.7419 .9574 .0538 .8681 .1673 Responsibility .6034 .5247 .9784 .0272 .8392 .2043 .5858 .5499 Structure .2514 1.1682 .9296 -.0888 .7217 .3587 .2295 1.2225 Peer-oriented .4268 .8049 .6229 .4952 .1564 1.4439 .0693 1.8726 Adult-oriented .3725 .9045 .7767 -.2854 .1919 1.3269 .3503 .9462 Auditory .6306 -.4856 .0289* -2.2595 .1498 -1.4678 .7836 .2767 Visual .2634 -1.1383 .4681 -.7320 .7223 -.3578 .1611 -1.4309 Tactile .0759 -1.8346 .0098* -2.7020 .0347* -2.1846 .0845 -1.7740 Kinesthetic .0698 -1.8761 .3281 -.9889 .0711 -1.8527 .7246 -.3551 Notes: The numbers in the left columns are p-value; those in the right columns are

t-value.

* indicates statistically significant difference at p< .05.

Table 4-4 T-tests for Differences in Learning Styles between the High and

listening, reading, speaking, and writing) were grouped as the high achievers (A1, A2, & A3); those who scored low in all tests were as the low achievers (B1, B2 & B3).

Low-Achievers in English proficiency Styles Receptive Skills

(df=37)

Productive Skills (df=30)

Holistic Skills (df=40) Motivation .0572 1.9628 .0221* 2.4143 .1044 1.6615 Persistence .8939 -.1343 .6395 -.4732 .9445 .0701 Responsibility .7704 .2940 .3494 .9506 .7228 .3572 Structure .8956 -.1322 .5745 .5677 .8234 .2246 Peer-oriented .2106 1.2741 .1121 1.6368 .2702 1.1180 Adult-oriented .9448 .0696 .0806 1.8082 .6640 .4376 Auditory .0330* -2.2150 .7890 -.2700 .0278* -2.2831 Visual .7168 -.3655 .2060 -1.2927 .7265 -.3523 Tactile .0276* -2.2943 .0122* -2.6661 .0266* -2.3028 Kinesthetic .1923 -1.3280 .4259 -.8073 .3377 -.9703 Notes: The numbers in the left columns are p-value; those in the right columns

are t-value.

* indicates statistically significant difference at p< .05.

Motivation v.s. English Proficiency

It was found that the high achievers in the written production and productive skills expressed a significantly stronger motivation than the low-achieving group. In other words, those with stronger motivation tended to did better in the written production and productive skills. This result was similar to that obtained from Multiple Regression that the subjects’ motivation was positively correlated with their performances in writing and productive skills. In fact, the high and low achievers’

degree of interest in English3 also confirmed that the high achievers liked English more than the low-achieving students.

Auditory Learning v.s. English Proficiency

Tables 4-3 & 4-4 show that the high achievers in reading, receptive, and holistic

3 Among the 3 high achievers, two of them chose 1 (I like English very much) and one chose 2 (I kind of like English); on the contrary, all the 3 bottom 3 members chose 4 (I dislike English).

skills showed a significantly negative preferences for auditory learning4. However, the means of the 6 interviewees’ learning styles 5 showed that the high achievers as a whole seemed to show a slightly stronger preference (M=9.7) for auditory learning than their low-achieving counterparts (M=9.2).

To confirm the t-test results, the interview data (see Appendix C, Part 1) from the high and low achievers were analyzed. The result showed that the high achievers expressed a slightly stronger preference for auditory learning than the low achievers6, as one of the high achievers pointed out:

Excerpt 17:

I’m used to learning through ear-hearing when it comes to learning common knowledge, because I can concentrate when I listen or discuss with others. I’m

more likely to get distracted when I’m reading. When I was in junior high school, I

used to listen to the radio program “Let’s Talk in English” every morning. I found it

was quite useful compared with reading the magazine. I would pay more attention to

the intonation of the teachers in the program. (from A1)

According to Excerpt 1, the auditory learners were likely to perform better on

4 The finding is different from Tsao’s (2003) and Park’s (1997) that the high achievers showed a significantly positive preference for auditory learning.

5 The distribution of the six interviewees’ learning styles was shown in the table below:

Table (i) Means of Learning Styles of the High and Low Achievers

Motivation Persistence Responsibility Structure Peer-oriented Adult-oriented Auditory Visual Tactile Kinesthetic

A1 13 10 12 11 15 10 13 10 12 13

A2 15 13 13 12 9 4 6 12 13 9

A3 15 7 9 12 13 9 10 10 8 11

Mean 14.3 10.0 11.3 11.7 12.3 7.7 9.7 10.7 11.0 11.0

B1 14 11 9 10 7 6 6 15 11 13

B2 14 13 13 11 12 6 9 13 16 15

B3 15 11 10 13 14 9 11 10 15 15

Mean 14.3 10.7 11.0 11.5 11.8 7.4 9.2 11.5 12.3 12.4

6 The low achievers showed a stronger preference for visual learning than the high achievers.

7 The interviews were conducted in Chinese and all the data were translated into English for analysis.

their English tests. In fact, a majority of the English teachers in Taiwan prefer instructing in an auditory fashion such as lecturing, reading instructions, asking students to read aloud, playing audio tapes, etc. (Cheng, 1997). Such teaching style tends to favor the auditory learners8, whose learning styles match their teachers’.

In contrast with the t-test results, the interview data supported the previous hypothesis suggested by the researcher that the design of the questionnaire might have something to do with the finding that the subjects’ auditory learning was negatively correlated with their English proficiency9, which was often reflected in reading comprehension10. Consequently, the difference in auditory learning between the high and low achievers was particularly obvious in reading comprehension. Besides, since there was no significant difference in listening comprehension between the high and low achievers, it is understandable that the t-test results concerning receptive skills echoed the finding of reading comprehension.

Tactile Learning v.s. English Proficiency

Tables 4-3 & 4-4 show that there were significant differences in tactile learning between the high and low achievers with regard to reading comprehension, oral production11, receptive skills, productive skills, and holistic skills.

The high and low achievers’ means of the learning styles5 showed that the

8 Hodges’s (1982) findings also confirmed that a majority of traditional classroom instruction for teenagers in U.S. secondary schools catered to the auditory learners.

9 Because most of the statements regarding the category of auditory learning involved expressions connected with “ discussion with others”. Since generally high achievers were considered more capable of learning on their own without discussion/others’ instructions, such statements were likely to cause the low achievers who preferred learning through discussion to respond positively in this auditory learning styles.

10 Of all the four skills, the correlation between reading skills and the other three skills was the strongest, implying that reading ability plays a crucial role in the master of the other three skills (See Table 3-4).

11 This result was inconsistent with the findings of Thomas et al. (2000) that there was no strong relationship between learning style and TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication) scores.

former as a whole had a lower preference (M=11) for tactile learning than the low achievers (M=12.3). Likewise, the interview data (see Appendix C, Part 2) showed that the high achievers didn’t like tactile learning while their low-achieving counterparts expressed a stronger preference for tactile learning, such as doing experiments. Therefore, the interview data confirmed the t-test results that the high achievers did not show preferences for tactile learning. To prepare students for the JCEE, English instruction in this school focused on the development of reading competence and seldom got students involved in hands-on activities. This might explain why the students who preferred tactile learning did not do well in English.

Moreover, it was found that tactile learners seemed to be more nervous when learning English (Cheng, 1997). They were afraid of being corrected by their English teacher.

Such attitude of being anxious12 and fearing making mistakes might affect their performance in English.

Besides, it is interesting that there was almost no difference in persistence (10.9 v.s. 10.8) and responsibility (11.2 v.s. 11.0) between the high and low achievers based on the subjects’ means of leaning styles. In addition, the high achievers seemed to have a stronger preference for peer-oriented learning than their low-achieving counterparts (11.6 v.s. 10.8). In order to confirm these results, the 6 high and low achievers were interviewed and the results are presented as follows:

Persistence/ Responsibility v.s. English Proficiency

Although the statistic result showed there was no big difference in persistence/

responsibility between the high and low achievers, the interview results (see Appendix

12 Scovel (1978, p.139) commented on Alpert and Haber’s (1960) distinction between facilitating and debilitating anxiety, “ facilitating anxiety motivates the learner to ‘fight’ the new learning task;

debilitating anxiety, in contrast, motivates the learner to ‘flee’ the new learning task; it stimulates the individual emotionally to adopt avoidance behavior.”

C, Part 3) showed that compared with their low-achieving counterparts, the high achievers as a whole showed more persistence/ responsibility. See the following two excerpts:

Excerpt 2:

If it is something I like, I’ll do my best. However, I’ll still make some efforts in

something I’m not interested in, if it’s necessary and important to me. For instance, I still spend some time studying math, though I don’t like it at all.(from A1)

Excerpt 3:

Compared with my younger brother, I am more self-disciplined and

responsible. So my parents have been very liberal in my upbringing. They seldom worry about my studies, because they think it’s my business. I can usually complete

what I should do on my own. If I hang out with friends before finishing my homework, I would feel very anxious. And I would feel very scared at being punished

by my teachers. (from A2)

On the whole, the high-achieving students would hang on to what they were doing, even though they were not interested in it. On the contrary, the low achievers’ persistence was “conditional,” just as B1 mentioned, “If I’m not interested in something I am doing, I often give it up in the middle of it.”

One possible explanation for the result that the high achievers did not show significantly greater persistence/ responsibility might be connected with the gender.

Because all the subjects in the present study were female students, who were generally considered self-disciplined and diligent. This might be why there was no significant difference in the persistence/ responsibility between the high and low achievers.

Peer-oriented Learning v.s. English Proficiency

Despite the fact that the high achievers seemed to have a stronger preference for peer-oriented learning than their low-achieving counterparts, the interview data (see Appendix C, Part 4) indicated that the high achievers generally preferred studying alone to studying with their peers. For example,

Excerpt 4:

I enjoy learning new things with my friends because I usually get more motivated.

However, I prefer to study alone because I would feel kind of uneasy and

uncomfortable when studying with my friend(s). And studying with them would distract my attention because sometimes we passed on notes to each other. (from A2)

In contrast with their low-achieving counterparts, the high achievers were more self-disciplined and aware of the risk of getting distracted when studying with their peers. On the other hand, the low-achieving students enjoyed studying with their peers more, just as B2 described herself, “ I prefer studying with my friends, because I can discuss with them”, showing that small group seemed to offer a “comfort zone”

for those with limited English proficiency. Obviously, compared with their low-achieving counterparts who benefited more from group discussion, the high achievers felt more secure when studying alone. This also implied that the high achievers were more capable of learning on their own.

4.3 Differences in Multiple Intelligences between the High and Low-Achievers To further examine if there were significant differences in multiple intelligences between the high and low-achievers, a series of t-tests were performed. Besides, interviews were conducted to confirm the t-tests results. The t-tests and the major interview results are presented and discussed in this section.

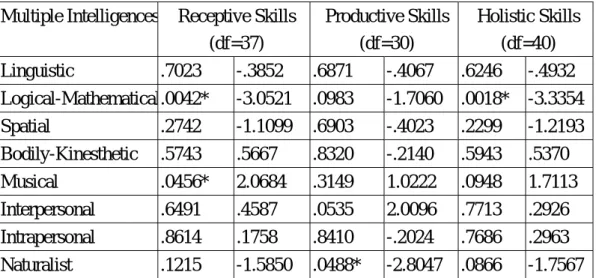

According to the t-test results in Tables 4-5 and 4-6, it was found that there were significant differences in naturalist, logical-mathematical, spatial, and musical intelligences between the high and low achievers, which are discussed respectively as follows:

Table 4-5 T-tests for Differences in Multiple Intelligences between the High and Low-Achievers in the Four Skills

Multiple Intelligences

Listening Comprehension

(df=32)

Reading Comprehension

(df=44)

Oral Production

(df=41)

Written Production

(df=36) Linguistic .1492 -1.4778 .4017 -.8467 .7050 .3812 .4768 -.7190 Logical-

Mathematical

.0023* -3.3178 .0033* -3.1034 .0784 -1.8049 .0365*-2.1726 Spatial .4442 -.7747 .0275* -2.2808 .7007 .3870 .4063 -.8402 Bodily-Kinesthetic .6516 .4558 .3549 -.9350 .7530 -.3168 .2715 1.1169 Musical .2020 1.3026 .4488 .7643 .7803 .2808 .0546 2.3459 Interpersonal .9781 .0277 .6723 .4259 .5698 .5730 .0693 1.8726 Intrapersonal .8675 .1682 .2162 -1.2548 .9096 .1143 .4564 .7530 Naturalist .1851 -1.3544 .0139* -2.5615 .2524 -1.1608 .2626 -1.1380 Notes: The numbers in the left columns are the p-value; those in the right columns are

the t-value.

*indicates statistically significant different at p< .05.

Table 4-6 T-tests for Differences in Multiple Intelligences between the High and Low-Achievers in English Proficiency

Multiple Intelligences Receptive Skills (df=37)

Productive Skills (df=30)

Holistic Skills (df=40) Linguistic .7023 -.3852 .6871 -.4067 .6246 -.4932 Logical-Mathematical.0042* -3.0521 .0983 -1.7060 .0018* -3.3354 Spatial .2742 -1.1099 .6903 -.4023 .2299 -1.2193 Bodily-Kinesthetic .5743 .5667 .8320 -.2140 .5943 .5370 Musical .0456* 2.0684 .3149 1.0222 .0948 1.7113 Interpersonal .6491 .4587 .0535 2.0096 .7713 .2926 Intrapersonal .8614 .1758 .8410 -.2024 .7686 .2963 Naturalist .1215 -1.5850 .0488* -2.8047 .0866 -1.7567 Notes: The numbers in the left columns are the p-value; those in the right columns are

the t-value.

* indicates statistically significant different at p< .05.

Naturalist Intelligence v.s. English Proficiency

Tables 4-5 and 4-6 show that there were significant differences in reading comprehension and productive skills between the high and low achievers’ naturalist intelligences. In other words, those with lower naturalist intelligences tended to do better in reading comprehension and productive skills. In fact, the means of the 6 interviewees’ multiple intelligences13 showed that the high achievers had lower

13 Table (ii) Means of the High and Low Achievers’ Multiple Intelligences

Linguistic

Logical-

mathematical Spatial Bodily-

kinesthetic Musical Interpersoanl Intrapersonal Naturalsit

A1 31 19 32 28 35 37 29 22

A2 31 24 31 35 30 35 31 15

A3 25 17 25 26 25 29 28 18

Mean 29.0 20.0 29.3 29.7 30.0 33.7 29.3 18.3

B1 34 29 39 29 25 28 42 38

B2 34 38 39 39 38 36 31 24

B3 31 22 27 29 31 30 29 28

Mean 30.7 24.1 31.8 30.8 30.6 32.7 31.3 23.3

natural intelligence compared with their low-achieving counterparts. Likewise, the interview results (see Appendix C, Part 5) showed that the high achievers did not show any interests in observing patterns in nature while their low-achieving group did.

One of them explained why she liked science-related subjects:

Excerpt 5:

For one thing, I think they are more interesting compared with subjects which

emphasize recitation like history and English. For another, the scientific theorycan be verified through experiments, which makes it easier to understand. That’s why I enjoy doing experiments. All in all, I cannot memorize things until I completely

understand it. Otherwise, I would feel my brain is too “full” to absorb things. (from B2)

According to B2, we can infer that in contrast with English, science was considered more logical for her because most of its theories could be verified through experiments and scientific procedures. On the other hand, English as a particular system of expressions used by foreigners, is an accumulation of historical background, customs, and habits, etc., which makes it seem to lack logic in essence. This might explain why those who had higher naturalist/ logical-mathematical intelligences usually found English grammars unreasonable and difficult to learn and therefore failed to perform well in English.

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence v.s. English Proficiency

With respect to logical-mathematical intelligence, Tables 4-5 and 4-6 showed that there were significant differences between the high and low achievers with regard to listening and reading comprehension, written production, receptive skills, and holistic skills. More specifically, the subjects with lower logical-mathematical

intelligences did better in their English tests. In fact, the means of the 6 high and low achievers’ multiple intelligences14 showed that the high achievers had lower logical-mathematical intelligences compared with their low-achieving counterparts.

Similarly, the interview results regarding the students’ logical-mathematical intelligences (see Appendix C, Part 6) revealed that all the high achievers considered math difficult to learn and got poor grades in it. Therefore, the interview data supported the t-test results that the subjects with better English proficiency generally showed a significantly lower logical-mathematical intelligence. Again, the tendency to learn through logical reasoning seemed to have a negative impact on the low achievers’ productive skills.

Spatial Intelligence v.s. English Proficiency

With regard to spatial intelligence, Tables 4-5 and 4-6 showed that there were significant differences in reading comprehension between the high and low achievers.

Likewise, the interview result (see Appendix C, Part 7) revealed that compared with their high-achieving counterparts, the low achievers in general showed more spatial intelligences. One possible explanation for this result might have to do with Taiwanese juveniles’ degenerate level of reading ability. As we know, an increasing number of young people nowadays prefer absorbing knowledge through pictures (e.g., comic books) instead of written words. However, the development of English reading ability mainly relies on a large amount of extensive reading. Since the ability to read pictures is an important index of the tendency for spatial intelligence, it is understandable why those who had more spatial intelligences did not perform well in their English reading comprehension tests.

Musical Intelligence v.s. English Proficiency

As for musical intelligence, Tables 4-5 & 4-6 showed that there were significant differences in receptive skills between the high and low achievers, too. That is to say, the students with higher musical intelligences did better in their receptive skills. In fact, the interview results (see Appendix C, Part 8) showed that in contrast with their low-achieving counterparts, the high achievers as a whole expressed a greater tendency for musical intelligence, as A1 mentioned, “I can usually remember the major melody of a song after listening to it once,” and A2 described, “I like imitating the intonation of people who talk in a special way.” Hence, the interview data confirmed the t-test results that the high achievers in receptive skills showed a significantly more musical intelligences. It also supported the result obtained from Multiple Regression that musical intelligence was positively correlated with the students’ listening ability and receptive skills. Obviously, a student’s sensitivity to perceive melody, pitch, and tone contributes to his/ her better receptive skills to certain degree.

4.4 The Relationship between EFL Students’ English Proficiency and Their Background Variables

Besides learning styles and multiple intelligences, the influence of background variables on the students’ English proficiency is another aspect to explore. Section 4.4.1 discusses the result with respect to the subjects’ experiences of studying English;

section 4.4.2, their parents’ attitude.

4.4.1 The Relationship between English Proficiency and Experiences of English Learning

The three questions concerning the subjects’ previous experiences of studying English included (see Appendix A): (i) when they started studying English, (ii) how long they had studied English, and (iii) how they liked English. Pearson Correlation Coefficients were performed to examine the correlation between the subjects’ English proficiency and the three variables. The results showed that there was a minor to moderate correlation between the subjects’ English proficiency and the span of their English study (r= .33, p<.01) and to what degree they liked English (r= -.38, p<.01), as can be seen in Table 4-7. Generally speaking, the longer the subjects had studied English, the better their English proficiency was. In addition, the subjects’ stronger motivation for English learning contributed to their higher English proficiency.

Table 4-7 Correlation between the Subjects’ English Proficiency and Experiences of English Learning

Question Items df p r

When they started studying English

106 .087 .10

How long they had studied English

106 .0001** .33

How they liked English 106 .0001** .38 Notes: ** indicates statistically significant difference at p< .01

Moreover, according to the interview data concerning motivation (see Appendix C, Part 9), the high achievers reported that they liked English for two main reasons: (a) Compared with the other subjects at school, their performance in English brought them a great sense of achievement; (b) it was fun and practical for

them to be able to communicate with native speakers of English. On the other hand, the low achievers disliked English because of the complexity of English, and no sense of achievement.

4.4.2 Parents’ Attitude

The interview data (see Appendix C, Part 10) showed that the high achievers were motivated by their parents, who put more emphasis on the importance of English learning:

Excerpt 6:

My mother has been very concerned about my academic performance, especially English. She thinks it’s very important to have good language proficiency, so she asked me to go to cram school to improve my English. I would be

blamed whenever I failed the tests. That’s why I’ve studied so hard. (from A3)

Excerpt 7:

My parents put a great emphasis on English. For example, to arouse my interest in English, they offered me a chance to go to the U.S. for a study tour. Also, my dad

often asks me to read some English novels and magazines. They also encourage me

to take the GEPT (intermediate level). (from A1)

Clearly, the high achievers’ parents put great emphasis on the importance of learning English. Moreover, they were often encouraged to do extensive reading.

On the contrary, the low achievers were less motivated and encouraged by their parents in learning English, which might partly contribute to their poor performances in English. To conclude, our result supports Milgram & Price’s (1993) finding that high achievers in foreign language were more parent-motivated.

4.5 Summary of Chapter Four

In this chapter, the researcher has further discussed and interpreted the findings reported in Chapter Three. Generally speaking, it was found that the subjects’

English proficiency was positively correlated with their motivation and their learning was peer-oriented while negatively correlated with their auditory and tactile learning.

On the whole, there were significant differences in motivation, auditory learning, and tactile learning between the high and low achievers. The high achievers showed stronger motivation but weaker preferences for auditory and tactile learning. With respect to multiple intelligences, it was found that the subjects’ English proficiency was positively correlated with their musical and spatial intelligence while negatively correlated with their naturalist and logical-mathematical intelligences. Moreover, there were significant differences in naturalist, logical-mathematical, spatial, and musical intelligences between the high and low achievers. The high achievers showed higher musical intelligences and lower naturalist, logical-mathematical intelligences. Besides, the subjects’ English proficiency was also positively correlated with the span of their English learning, their interest in English, and their parents’ attitude.