The Impacts of Buddhism in

Hakka Business Management

鍾振華

Abstract

There is a relative dearth in studying the impact of religions on the Hakka culture. This is particularly true for the case of Buddhism. Like most folk religions, Buddhism has been deeply rooted in Hakka societies. Such deep root implies the existence of tremendous impacts which Buddhism exerts upon the Hakka culture. Such impacts certainly deserve more attention by Hakkaology researchers. This research intends to fill the aforementioned gap by investigating the impacts of Buddhist thoughts on the business and management philosophies of Hakka enterprises. A total of 21 Hakka entrepreneurs are interviewed. Although not all of them are self-claimed Buddhists, they are generally open-minded and receptive to Buddhist thoughts. Their management styles, practices and philosophies are quite compatible with both Buddhist and Hakka values. Based on the result of this study, we further propose a preliminary Buddhism-based management model for Hakka enterprises.

1. Introduction

Max Weber (1904-1905, 1958) is the pioneer of investigating the impacts of religiousthoughts on economic activities. He believes that

Protestant ethic is the spiritual foundation ofcapitalism. That is, the Protestant ethic has fostered the social psychological conditions which make possible the development of capitalist civilization in the Occident. He suggests that the connection between economic rationalism and a sense of religious

responsibility stems from the ethics of ascetic Protestantism. Using a similar analysis, he further concludes that due to the effects of the Confucian ethos, rational entrepreneurial capitalism would be retarded in societies influenced by the Confucianism (Weber 1951, p. 104). Weber‟s thesis of the

and economic activities through culture.

In the management literature, there have been studies exploring the impacts of Buddhist thoughts (particularly Zen Buddhism) on management styles. For example, Pascale and Athos (1978, 1981) discussed the

relationship between Zen Buddhism and Japanese management.

Unfortunately, their shallow understanding or even misunderstanding of Zen Buddhism has resulted in wrong conceptions about such relationship. Specifically, they consider “ambiguity” to be what Zen is all about and consequently the management should purposely “create ambiguity”. This is certainly not a correct understanding of Zen and thus can be a dangerous attitude for management.

There is a relative dearth in studying the impact of religions on the Hakka culture, not to mention how religious thoughts may influence the management practices of Hakka enterprises through the force of the Hakka culture. Like most folk religions, Buddhism has been deeply rooted in Hakka societies. Such deep root implies the existence of tremendous impacts which Buddhism exerts upon the Hakka culture. A cursory look at the Hakka culture would give us many traces of Buddhist thoughts which have been ingrained in Hakka people. For example, the Buddhist concepts such as giving,

performing good deeds, the law of cause and effect, etc., are well accepted by Hakka people. Such impacts certainly deserve more attention by Hakkaology researchers.

interviews and other forms of continuous interactions with over twenty Hakka entrepreneurs, we gain a good understanding of the roles which Buddhism plays in Hakka culture and the management styles of Hakka enterprises. This study not only bridges some gaps in Hakkaology research, but also widens the perspectives on Hakka cultures.

The study of the impact of religions on organization management can and should be viewed in the broader context of cultural approaches to organizations and, in parallel, the cultural exploration in the social sciences (e.g., Morrill, 2008; Smircich, 1983; Weeks and Galunic, 2003). Cultural roots play an important role in shaping both the conceptions of organizations and the resultant management styles. This fact has been well documented in the literature (e.g., Allaire and Firsirotu, 1984; Alvesson and Berg, 1992; Burrell and Morgan, 1979, Deal and Kennedy, 1982). Threading such investigation through the factor of ethnic cultures (e.g., Hakka) can be fruitful and valuable to the understanding of organization management. Nevertheless, this is indeed a fertile but yet-to-be-cultivated research field.

In this project, we study how Buddhist thoughts impact the business and management philosophies of Hakka enterprises. Through interviews and other forms

of continuous interactions with over twenty Hakka entrepreneurs, we gain a good understanding of the roles which Buddhism plays in Hakka culture and the management styles of Hakka

insights into the aforementioned cultural approaches to organization sciences (and social sciences, for that matter).

2.Research Protoco

lTo investigate the impacts of Buddhist thoughts on the business and management philosophies of Hakka enterprises, we contacted 30 and successfully interviewed a total of 21 entrepreneurs with varying degrees of in-depth investigation. As shown in Appendix I, these entrepreneurs represent a variety of businesses, including manufacturer and exporter of automobile parts, restaurant owners, publishers, retailers, etc. Interviews were conducted via telephone, e-mail and face-to-face discussions. There is at least one “follow-up” conversation with each of the interviewees.

A set of selected Buddhism-related topics were used as guidelines for interview. We asked the interviewees about their understanding of these concepts. What do they think about these concepts? Have they related or applied these concepts to their

management practices? What are the results of the applications? We also encouraged them to go beyond the selected topics and freely talk about their management styles, practices and philosophies. Memorable experiences, episodes of events, stories and lessons, etc. are particularly welcome. The selected list of topics is briefly described as follows:

(1)Oneness.

subject vs. object, leader vs. followers, etc. Despite the notion of “synthesis, Hegel‟s Dialectics starts with the opposition between thesis and anti-thesis. Although oneness can be considered the anti-thesis of dualism, the true oneness should transcend the dualism between oneness and dualism. Ironically, the notion of transcendence is itself dualistic. By the same token, the true oneness should “transcend” the contrast between dualities such as one versus many. Such transcendence then leads to the concept of “Middle Path of Eightfold Negations” (中道八不) – the doctrine established by Bodhisattva Nagarjuna: (there is) no production, no extinction, no

annihilation, no permanence, no unity, no diversity, no coming, and no going” (不生、不滅、不斷、不常、不一、不異、不來、不去).

(2)The Middle Path.

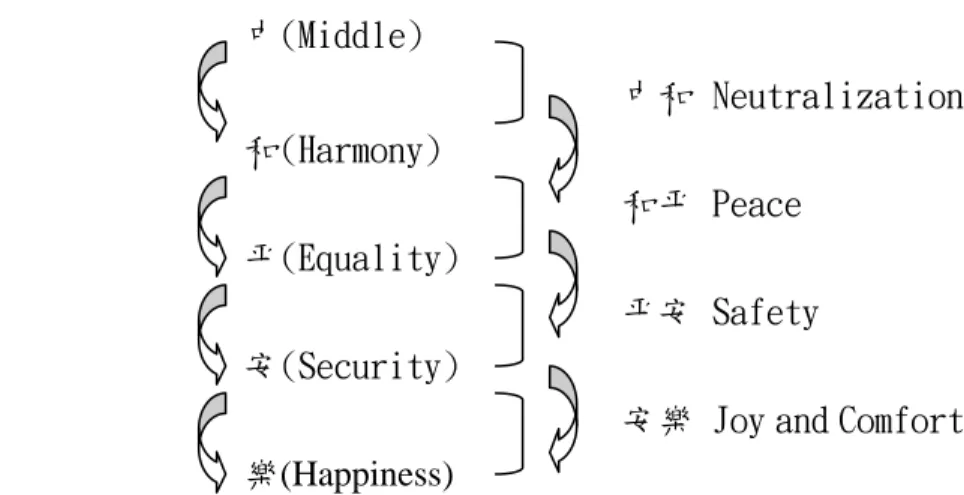

The concept of Middle Path is crucial to the harmony of an organization and to managerial effectiveness. Figure 1 sketches such a relationship.

Figure 1. The Middle Path and Harmony

中(Middle) 中和 Neutralization 和(Harmony) 和平 Peace 平(Equality) 平安 Safety 安(Security)

安樂 Joy and Comfort 樂(Happiness)

in hand with equality. Equality is prerequisite to a peaceful state since any inequality is likely to cause agitation or unrest. Finally, peace is a necessary condition for happiness. In the context of business management, one can further to assert that happy employees are quality and productive employees. Thus Figure 1 suggests that the Middle Path is crucial to both effectiveness and efficiency in organization and management.

(3)Emptiness.

In Buddhism, emptiness does not mean “nothing”. Rather, it implies “infinite possibilities. On the other hand, emptiness characterizes the true nature which is inherent in all things (i.e., all manifestations of the true nature).

(4)The Law of Cause (with Conditions) and Effect.

This is why the transition or transformation process is always “continuous.” Third, any process is just a collection of numerous cyclical causes and effects. Any cause is an effect of past causes. Any effect will be the cause for future effects. Thus, any process is a cyclical process of causes and effects. Any “state” is, in fact, simultaneously the effect of past causes and the cause for future effects (i.e., future “states”). With these three properties, the Law of Cause and Effect is said to be “never empty”. Furthermore, causes will produce effects only “when conditions are right”.

Conditions are thus called secondary causes. The effects are called “conditional occurrences”.

(5)One-Mindedness.

3.Findings and Discussions

Although not all of the Hakka entrepreneurs with whom we have exchanged ideas are self-claimed Buddhists, they are generally open-minded and receptive to Buddhist thoughts. In fact, their management styles, practices and philosophies are quite compatible with both Buddhist and Hakka values. Like most social phenomena, the causal relationship between Buddhism, Hakka value and the management styles

and philosophies of Hakka enterprises may not be easily proved or verifiable. However, the connections are definitely there. We consider our research methodology is a type of “triangulation” – an attempt to look at issues or phenomena from different perspectives.

Among the five Buddhist concepts listed as the guideline for interview, the Law of Cause and Effect are most commonly applied, one way or another, by Hakka entrepreneurs. The “oneness” and the Middle Path concepts follow closely. They treat the “mindfulness” or “one-mindedness” concept with a “common sense” attitude, not necessarily in the context of “true mind” in the Buddhist literature. The “emptiness” concept seems to be rather abstract to most of them. Like most people would, they interpret it simply as

“non-attachment” or the need to let go of worldly things. The findings in each of these and related topics will be discussed below.

“good intentions.” One should not sacrifice righteousness for profit. One should not seek benefit at the expense of others. The “law of retribution” should always be kept in mind in conducting business. This is the foundation of business ethics. This unique characteristic is quite different from the way Western managers and Western management theories treat the issues of business ethics.

The owner of a small business gave the following “testimony”: A majority of his employees is Hakka. He claims that he treated all his

employees (including the non-Hakka) as family members. (He believes this is one of the core Hakka values). He has been quite generous to his employees in terms of pay and fringe benefits. One year during the economic downturn, his company ran into deep financial trouble. He insisted to keep all

employees on job even though there was really not much job due to lack of business. Many of his employees proposed voluntary pay cuts. He hesitated because he claimed to be a “typical Hakka” who is “hard-neck” stubborn and can “swallow anything”. Eventually, he accepted their good-will, but not their offer. Then,

pretty soon, the business turned around. He firmly believes this is the Law of Cause and Effect at work.

partnership and lost all his investment. Interestingly, he claims that trusting people too easily should not be a Hakka personality. But he believes that Hakka people tend to be simple, if not naïve, in terms of human relations. He took responsibility for his failure by citing the law of cause and effect. He is not alone. Most of the Hakka entrepreneurs in this study express their appreciation of the importance of the causal law in business management. They believe this is particularly true in “change management”. They agree with Aristotle‟s assertion that all changes are caused. A business process, like any process, consists of numerous causes and effects. Earlier we quote a famous assertion in the Buddhist literature – “All dharmas (i.e., all things) are empty while the Law of Cause and Effect is never empty.” As mentioned earlier, there are three fundamental properties of any causal process which explain why the Law of Cause and Effect is never empty. These three properties also have profound implications for business management. First of all, any causal process is a “transformation” process. Since causes always lead to some effects, the episode of going from causes to effects is a transformation or a transition process. In business management, all

organizational activities are nothing but an input-throughput-output process which is a transformation process converting inputs into outputs. One entrepreneur comments that one can visualize the business processes as nothing but the continuous transformation process of causes and effects. Such a perspective helps us trace the process of causes and effects and thus the “root causes” of problems. We can then see how we can “control” the causes and the

conditions” is in the minds of many Hakka Entrepreneurs. Second, the transformation or transition is a continuous process. However, such continuity is simply an illusion. According to Aristotle, change is going on constantly. There is a simultaneous production and extinction of the states. Consequently, there are literally no “gaps” between states. This is why the transition or transformation process is said to be “continuous.” It is not coincident that business management, like the accounting principle, is dealing with a

continuous process and thus should be conducted on the assumption of going concerns. On the other hand, the so-called “states” (in any process) are transitory because of the simultaneous production and extinction of states. In other words, these states are literally inexistent.The

“getting-from-here-to-there” mentality in the traditional change management model is nothing but creating the illusion of certainty where there is none. This is what the ancient philosopher, Lao Tzu, referred to as “trying to understand running water by catching it in a bucket.” Third, any process is just a collection of numerous cyclical causes and effects. Any cause is an effect of past causes. Any effect will be the cause for future effects. Thus, any process is a cyclical process of causes and effects. A “state” is simultaneously the effect of past causes and the cause for future effects (i.e., future “states”). With their firm belief in the Law of Cause and Effect, most Hakka

task of management should be considered as nothing but to create favorable “conditions” for their business – the conditions which convert causes into effects.

Many Hakka entrepreneurs have an interesting interpretation of the notion of “oneness”. They emphasize the importance of “whole picture” and thus “big picture” in business management. This is particularly true in making strategic decisions. Thus,

“oneness” means not to overlook any aspect of the business. All aspects are equally important. The oneness concept is also extended to the time

dimension. That is, big picture implies long-term view, visions, etc. The oneness concept also implies “integration.” Integration leads to minimization, if not total avoidance, of dualistic opposition, contrasts, or even conflicts. Substantial tasks in management are conflict resolution in nature. Indeed, one may consider the task of organization management as nothing but to dissolve any conflicts or dualities. For this reason, the oneness concept is closely related to the Middle Path thesis and the entailed issue of organizational harmony.

would not do good jobs if they are in bad mood. A harmonious organization also provides a better chi (energy, atmosphere, or “magnetic field”) for working environment. Thus the chain in Figure 1 suggests that the Middle Path is crucial to both effectiveness and efficiency in organization and management. With the exception of two or three truly devoted Buddhists, most Hakka entrepreneurs in this study treat the “mindfulness” or

“one-mindedness” concept with a “common sense” attitude. That is, they do not see it in the context of “true mind” in the Buddhist literature. But their attitude toward “mindfulness” and their management practices are quite consistent with the implications of the “true mind” concept. For example, one Hakka entrepreneur talks about one episode of his experience in making “big decisions”. He was facing the decision of acquisition of a small company. He was torn between pros and cons related to the purchase. Then he made a point to take off three days and leave the decision behind. For three days, he

enjoyed hiking and sight-seeing, without a single thought placed upon the “big decision”. After he got back, he had much clearer head (i.e., “purer mind”). He made a decision on the acquisition. He believed he had made the correct decision. Several Hakka entrepreneurs relate similar experience, perhaps not so drastic as “leaving the scene”.

Another interpretation of the Middle Path thesis is the avoidance of being too much or not enough. One Hakka entrepreneur, whose company has been in business of manufacturing and exporting auto parts for years,

best location, the proximity to customers is generally considered one of the most important concerns. Customers will definitely be very happy if suppliers are in close vicinity so as to get fast shipments and services. Under

competition, suppliers are likely to locate closer to customers and to develop close ties with them. However, this particular Hakka entrepreneur gives a different perspective. According to him, if you locate close to customers, they may take things for granted. If you

keep them at a reasonable distance, you can reduce the unreasonable

demands from you customers – “they won‟t bother you if it‟s not convenient for them to do so.” This is indeed an art of applying the Middle Path thesis.

With the exception of two or three truly devoted Buddhists, most Hakka entrepreneurs in this study treat the “mindfulness” or “one-mindedness” concept with a “common sense” attitude. That is, they do not see it in the context of “true mind” in the Buddhist literature. But their attitude toward “mindfulness” and their management practices are quite consistent with the implications of the “true mind” concept. For example, one Hakka

entrepreneur talks about one episode of his experience in making “big decisions”. He was facing the decision of acquisition of a small company. He was torn between pros and cons related to the purchase. Then he made a point to take off three days and leave the decision behind. For three days, he

decision makers can “empty” out delusive thoughts from their minds, they will definitely have a clearer head to make better decisions.

As mentioned earlier, in addition to the above five topics, we encourage interviewees to have open discussions on their management practices,

experiences, memorable moments in their business and careers, as well as their views on various issues related to this study. We would like to detect any Hakka and/or Buddhist “flavors” in their inputs. This part of exchanges proves to be very fruitful.

Perhaps due to the fact that Hakka people are big on “blood ties”, most Hakka entrepreneurs have one way or another emphasized the importance of the “family” concept. That is, they tend to consider a business firm as a family and treat employees as family members. Many of them feel the obligation to look after their employees. Unless absolutely necessary, they try their best not to lay off workers. It should be noted that, although being big on blood ties, they do not discriminate against non-Hakka people, in hiring, compensation, rewards and promotion, as well as in employee welfare in general. Several Hakka entrepreneurs purposefully pointed out that they are in business to take care of others, rather than simply to make money. Take care of other people; the business will take care of itself. To be exact, take care of other people, other people will take care of your business. This is just another example of the causal law at work.

they really appreciate the idea that quality consists of three ingredients: attention to details, hard work and dedication. One of them even points out that these three ingredients are quite compatible with the generally accepted description of Hakka people – “hard neck” (i.e., stubborn or insistent), thrifty and diligent. Indeed, dedication requires “hard neck”. Hakka people are generally hard workers. When you are thrifty, you will definitely pay attention to details. This attitude is something more than the advice that a penny saved is a penny earned. As one entrepreneur puts it, “Save nickels and dimes now; a lot of businesses need you to invest in the future.

Another Buddhist idea which the Hakka entrepreneurs frequently mentioned is the notionof “yuan” (緣). There are many more subtle connotations of this term. In fact, it is more than what is commonly know meaning of “conditions”, as in the context of cause-condition-effect. In organization management, it may mean affiliation, connection, or relation in the cases of human relations. It may also mean opportunities for activities. Hakka entrepreneurs often emphasize the importance of build good connections. They also talk about the need to be ready when opportunities knock. As one Hakka entrepreneur puts it, “In life or in our careers, you often need someone, powerful people or guarding angels, to lend you a hand. But you must prepare yourself for taking advantage of such help or

One unexpected, but not surprising, finding in our study is that most of the Hakka entrepreneurs show great sense of humor. Perhaps this is simply a natural (and necessary) tendency for people who is hard working or in adverse circumstances. A sense of humor not only provides relaxation, but also carries people through adversity. Thus, this quality should go hand in hand with the Hakka traits such as hard work and hard neck. This should be an interesting topic for future studies in Hakkaology. Interestingly, people should also find that the Buddha indeed has great sense of humor too. In many of the Buddha‟s teachings, particularly the stories, metaphors, analogies, etc. told by the Buddha, we can appreciate his sense of hum or

4.Toward a Buddhism-Based

Hakka Management Model

As a summary of the study reported above, we propose a preliminary Buddhism-based Hakka management model. As the name suggests, the model should incorporate both the Buddhist concepts and the traits of Hakka people and Hakka culture.

The model is adapted from the traditional Confucian framework of the triad of monarch, parent and teacher. No doubt, modern interpretation of these terms is necessary since the “monarch” concept is out of date. This

Table 1. The Buddhism-Hakka Connections in the Monarch-Parent-Teacher Triad

Traditional Modern Buddhist Hakka (Confucian) Concepts Values Values

Concepts

Monarch Leader -- Four Types of -- Reverence for Benevolence * Ancestors,Deities, etc.

Parents Parents -- Filial Piety -- Filial Piety (Love and Care) -- Compassion -- Cherish “blood ties” Teacher Teacher -- Respect Teache - Respect Teacher

(Education and -- The Buddha as -- Respect Books and Edification) the “Original Papers containing Teacher Writings

*

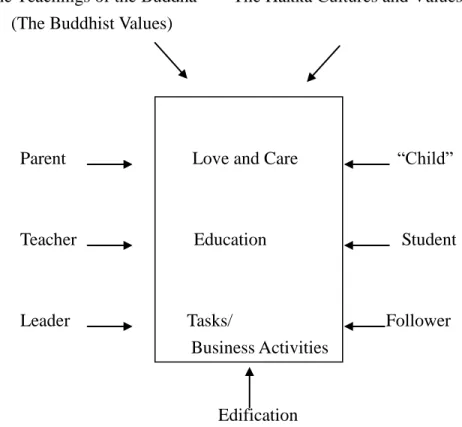

Figure 2. A Buddhism-Based Hakka Management Model

The Teachings of the Buddha The Hakka Cultures and Values (The Buddhist Values)

Parent Love and Care “Child”

Teacher Education Student

Leader Tasks/ Follower

Business Activities

Edification It is commonly believed that a leader is the “central point” of an organization. However, a leader is at the same time a follower. Also, any organization member is both a leader and a follower simultaneously. Thus, any organization is really a “centerless network” – a network of partners. To be exact, every member is a center. All members are equal because they are partners. Thus, a CEO is in equal status with a sanitary engineer (i.e., a janitor) – they are partners.

addition to being both a leader and a follower simultaneously, any organization member would also be both a “parent” and a “child” simultaneously and be both a teacher and a student simultaneously.

It should be noted that the relationship between parents and children is a two-way street. Parents love and care about their children. Children also love and care for their parents. Similarly, teachers teach students and also learn from students. If a leader is at the same time a follower, we can analogously conclude that a parent is at the same time a “child” and that a teacher is at the same time a student.

In interacting with colleagues, organization members are teaching each other and learning from each other. Therefore, any organization member is a teacher and a student at the same time. On the other hand each member is a parent and a child simultaneously. By “parent is at the same time a child,” we do not refer to the parent‟s role as his or her parents‟ child. Rather, a parent is a “child” to his or her own children. This may sound absurd. However, it is only human nature that parents, from time to time, are longing for their children‟s attention, respect, love, care, etc. (Worse yet, parents are sometimes very “childish”.) Furthermore, we can define a parent as someone who is on the giving end, while a “child” on the receiving end, of love, care, etc. Every human being needs love and care. Any human being is capable of giving love and care. In fact, it is a human nature to love and to care. Thus, any

organization member can and should be a parent and a child simultaneously. As a partner, any organization member plays the six roles of leader/follower,

When we say that “an organization member plays the six roles

simultaneously,” we do mean simultaneously. For example, parents not only

love and care for their children, but also, as a leader, set examples for their children. On the other hand, children not only love and care for their parents, but also serve as “teachers” to their parents. Children are fast-learners. Oftentimes, parents simply cannot catch up with their kids. A majority of adults have to turn to their youngsters for help with computers, internets, etc. Also, from time to time, children are the best leader or role model for their parents. Most children are pure, honest and straightforward. They are generally not tricky and treacherous like some adults. Their minds are not contaminated.

Like the six roles being an integrated one, the “activities” associated with the three pairs of relationship (i.e., love and care, education, and business tasks) are also an integrated one. The three types of activities are indeed inseparable. For example, employees need to be taught in order to carry out various tasks in the organization.

Chung (2011) suggests that we should look into the cultural politics‟ perspectives of Hakkaology. Cultural politics is “the complex process by which the whole domain in which people search and create meaning about their everyday lives is subject to politicization and struggle” (Angus and Jhally, 1989). The evolution and development of Hakka values and all activities which Hakka people engage in would necessarily involve the search and create meanings while such processes are inevitably subject to

evolution and development of Hakka culture (or for any culture or

sub-culture, for that matter). Obviously, the management practices of Hakka enterprises are no exception – as shown in Figure 2.

The notion of “edification” is adapted from Rorty (1979). He coins this term to stand for the project of finding new, better, more interesting, more fruitful ways of speaking. Thus, implicit in this term is a dynamic and interactive process which goes on in all human relations. The term

“edification” is used in place of “education” because the latter may give the impression of simply “the transfer of knowledge.” The aim of edification is at continuing a conversation – conversation with oneself and with others -- rather than at discovering truth. The purpose of continuing conversation is to enhance understanding, consciousness and awareness, rather than just “knowingness.” Thus the notion of “edification” serves well for describing the dynamic interactive process of business activities, love/care and education as discussed in the previous section. Indeed, all three types of organizational activities which partners engage in -- love/care, education/learning, and tasks/business activities – involve “continuing

conversations.” Effective partnership would require organization members strive for enhancing understanding, awareness and consciousness. These concepts can be best summarized by the following three premises associate with the edification and re-description.

• Edification enhances people’s consciousness and awareness, rather than

knowingness and pigeonholing, of what goes on in the field.

• Edification helps people expand their horizons of understanding.

understanding.

The edification philosophy entails at least two closely related requisites for successful management through the process of constant re-description (i.e., a continuing conversation). First, the edification philosophy advocates

open-mindedness and therefore the importance of both extending horizon and widening perspectives. Second, the edification philosophy encourages

creativity for coming up with new and novel descriptions. Open-mindedness can remove many unnecessary constraints and obstructions to the generation of creative ideas required by the re-description activities. With extended horizon of understanding and widened perspectives, one becomes more receptive to new and novel ideas. One will be able to see bigger pictures. This, in fact, helps one maintain strategic focus.Open-mindedness also sets one free from the fixation on his or her own value systems, conceptual

frameworks, or favorite descriptions. One then becomes more conscious and aware of the circumstances and more sensitive to changes in the environment. There are at least two (again, closely related) ways to enhance both

open-mindedness and creativity. First, one may find it useful to use

use metaphors and extend them to different problem settings without worrying about issues such as replicability and generalizability. As Frisina (2002) puts it, “We can let go of the effort to describe the world „as it is‟ and enjoy the unmitigated pleasure of creatively playing with metaphors that we use to constitute ourselves and the world around us.” (p. 38) The notion of “continuing re-description” suggests that these descriptions can hardly be qualified as “truth” – because they are changing constantly. Another important way to enhance open-mindedness and creativity is to develop habitual “mindfulness.” In recent years, the issue of mindfulness has received increasing attention from researchers in organization science. Langer (1997) specifies the concept of mindfulness as a state of active awareness

characterized by the continual creation and refinement of categories, an openness to new information and a willingness to view contexts from multiple perspectives.

Earlier we mentioned that most of the Hakka entrepreneurs in this study (like the Buddha) show great sense of humor and that such sense of humor can facilitate not only teaching, but also effective communication in

organizations. During the re-description process, stories, metaphors, analogies, etc. are often used. Such usage

5.Conclusions

In this study, we intend to investigate the impacts of Buddhist thoughts on the business and management philosophies of Hakka enterprises. We interviewed a total of 21 entrepreneurs. They represent a variety of businesses. A set of selected

Buddhism-related topics were used as guidelines for interview. Although not all of the Hakka entrepreneurs in this study are

self-claimed Buddhists, they are generally open-minded and receptive to Buddhist thoughts. Their management styles, practices and

philosophies are quite compatible with both Buddhist and Hakka values.

Among the five Buddhist concepts used as the guideline for interview, the Law of Cause and Effect are most commonly applied by Hakka entrepreneurs. The “oneness” and the Middle Path concepts follow closely. They consider the “mindfulness” or “one-mindedness” concept just a “common sense” for conducting business, rather than what is called the “true mind” in the Buddhist literature. The

“emptiness” concept seems to be rather abstract to most of them. They interpret it simply as “non-attachment” or the need to let go of worldly things.

Hakka values are integrated in this model. Since it is “preliminary”, the model should be further fine-tuned by incorporating more Buddhist theses and Hakka values. For example, in the Buddhist literature, the following eight factors are consider important perspectives one should take when dealing with worldly affairs: Essence (體), Phenomena (相), Functions/Applications (用), Causes (因), Conditions (緣), Effects (果), Universals (理) and Particulars (事). These eight factors should, one way or another, be

incorporated into business management processes.

Future studies should also be directed to more comprehensive and comparative investigation of the impacts of Buddhism upon other ethnic groups or subcultures. In this way, we can have a better

understanding of the unique characteristics and styles

(if any) of Buddhism oriented Hakka business management, as contrast to those in other subcultures. Similarly, the proposed

preliminary Buddhism-based Hakka management model needs to be further fine-tuned and tested in different environments. After all, as suggested by the aforementioned “edification” concept, the evolution and development of the Hakka culture, of Hakkaology, and of the Hakka

References

Allaire, Y. and Firsirotu, M. (1984) “Theories of Organizational Culture,”Organization Studies, 5(3), pp. 193-226.

Alvesson, M. and Berg, P. O. (1992) Corporate Culture and

OrganizationalSymbolism, Berlin: De Gruyter,

Burrell, G. and Morgan, G. (1979) Sociological Paradigms and

Organizational Analysis, London: Heinemann,

Angus, I. and Jhally, S. eds. (1989) Cultural Politics in

Contemporary America,Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc.

Argote, L. (2006) “Introduction to Mindfulness”, Organization Science, 17(4), p. 501.

Calder, G. (2003) Rorty, London: Wiedenfeld & Nicholson. Chang, W. A. (2007)“An Investigation on Hakka Entrepreneurs in Taiwan”, 張維安 (2007)「台灣客家企業家的探索」(客家委員會講 助計劃結案報告).

Chung, C. H. (1985), “Reshaping the Mentality for Productivity”,

Operations Management Review, Fall, pp. 25-29.

Chung, C. H. (1994), "Beyond A Science of Operations Management," Decision Line, Vol. 25, No. 5, September/October, pp. 8-9.

Chung, C. H. (1999) "It's The Process: A Philosophical Foundation for Quality Management,”Total Quality Management, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 179-189.

Chung, C. H. (2003) “A Supradisciplinary Approach to Decision and ManagementSciences Research,” Proceedings of 2003 Midwest

Decision Science Institute Meeting, Miami, Ohio.

Institute Meeting, Boston.

Chung, C. H. (2005), “Towards a Philosophy of Decision and

Management Science,” Proceedings of 2005 National Decision

Science Institute Meeting, San Francisco.

Chung, C. H. (2009) “Hidden Potential and Imprints – A New Theory of Quality”, Working Paper, University of Kentucky.

Chung, C. H. (2011) “Hakkaology: A Cultural Politics Perspective”, Presentation at National Pingtung University of Education, March 11.

Chung, C. H. (2011) “Towards a Philosophy of Decision and

Management Science,” International Journal of Business Research

and Management, (forthcoming).

Chung, C. H. and J. Chung (2008) “Conductor Is Just Another Musician: Partnership As Leader-Member Interaction”, Journal

of Business and Leadership.

Chung, C. H., J.M. Shepard and M. J. Dollinger (1989), “Max Weber Revisited: Some Lessons from East Asian Capitalistic

Development”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 6, No. 2, PP. 307-321.

Deal, T. and Kennedy, A. (1982) Corporate Cultures, Reading,Mass.:Addison-Wesley.

Frisina, W. G. (2002) The Unity of Knowledge and Action: Toward a

Nonrepresentational Theory of Knowledge, State University of

New York Press.

Longmeadow Press.

Langer, E. J. (1997) The Power of Mindfulness, Cambridge MA: Perseus Books.

Levinthal, D. and Rerup, C. (2006) “Crossing an Apparent Chasm: Bridging Mindful and Less-Mindful Perspectives on

Organizational Learning,” Organization Science, 17(4), pp. 502-513.

Miyamoto, M. (1982) The Book of Five Rings, New York: Bantam Books.

Morrill, C. (2008) “Cultur and Organization Theory,” Annals

American Academy Political Social Science, 619, pp. 15-40.

Pascale, R. T. and Athos, A. G. (1978). “Zen and the Art of Management”, Harvard Business Review, March-April. Pascale, R. T. and Athos, A. G. (1981). The Art of Japanese

Management, New York: Warner Books.

Rorty, R. (1979) Philosophy and the mirror of nature, New Jersey: Princeton Unversity Press.

Rorty, R. (1991) Objectivity, Relativism and Truth, Cambridge University Press.

Smircich, L. (1983) “Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(3), pp. 339-358.

Weber, M. (1951), The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, translated and edited by H. H. Gerth, New York: Free Press. Weber, M. (1958), Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism,

translated by T. Parsons, Charles Scribner‟s Sons. Weeks, J. and Galunic, D. C. (2003) “A Theory of the Cultural

Evolution of the firm: The Intra-Organizational Ecology of Memes,” Organization Science, 24(8), pp. 1309-1352.

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M. and Obstfeld, D. (1999) “Organizing for High Reliability: Processes of Collective Mindfulness,” B. Staw and R. Sutton, eds., Research in Organizational Behavior, 21, Greenwich, CT: JAI, pp. 81-123.

Appendix I

List of Hakka Businesses Participated in this Study

** We do our best to preserve the privacy and anonymity of the interviewees.

1. Accounting Firm This accounting firm specializes in international and domestic,

business and personal taxes. The company is headquartered in the U.S. But it has extended its business to East Asian countries. The founder who is also the current owner of the company is a Buddhist. 2. Architect

The architect received a master‟s degree from University of Kentucky and a

Ph.D. degree from University of Florida. After he returned to Taiwan, he first became a partner in an architect firm and later had his own company. As both an architect and a developer, he established his business and reputation in Central Taiwan area. Sadly, he passed away in April, 2011.

3. Auto Parts Design, Manufacturing and Export The company was founded more than thirty years ago. Currently it has over 100 employees. The company Headquartered in Southern Taiwan with warehouses and offices in the U.S. This Hakka

latter venture accounts for about 10% of the company‟s overall profit. It provides a cushion for the company‟s financial health. This is particularly important move since the export business is too sensitive and vulnerable to the global recessions.

4. Car Dealer This is, in fact, a failed business. The car dealership was a joint

adventure in China. The Hakka “entrepreneur” put up the majority of the capital while the counterpart Chinese partners provided the “local connections” with local government to obtain land, showroom building, license, etc. Less than three years, after the business stabilized, the Hakka entrepreneur was kicked out of the partnership and lost all his investment. Before this failure, the Hakka

entrepreneur did have a successful

transportation company (focusing on limousine services) in Southern Taiwan.

5. Convenient Stores (2) One traditional, the other franchisee of a major chain. The

traditional store is just a typical Mom and Pop store.

6. (Director of) Branch Office of a Nonprofit Organization Founder of a branch organization of a Buddhist foundation in a major (Midwest U.S.) city.

7. Engineering Consulting (2) Both major in Civil Engineering with concentration on

“structure engineering”; one focuses on water-related projects and the other more into construction business. Both got their master‟s degree from University of Kentucky. 8. Engineering Design (2) One has aerospace industry as major clients. The other is a

software engineering company. Both in California, U.S.A.

10. Orchid Farmers (2) One engages in farming only, the other also in sales.

11. Publishers (2) They are publishers of magazines and books, one founder of a

magazine and the

other successor. The latter has expanded the operation into publication of additional magazines and books. The magazine

managed to survive and celebrated its twentieth anniversary in 2010.

12. Restaurants (3) One owns 3 restaurants, another owns 3 at different times, and

the third one owns 4 at different times. The first is in Taiwan while the latter two in the U.S.

13. (Senior Executive of a) Utility Company

The senior executive has a master‟s degree from the U.S. Before joining the company, he had work for television maker, a company of Formosan Corps, and one research institute. He even had a short stint in teaching technical college.

14. Tea Sellers (2) One has an on-line business in selling tea, but not a very

Appendix II

Sample Conversations with the Interviewees

***

“We are in the business of helping people save and manage money. We always emphasize that saving money and good financial management should be oriented to „love‟ – the love for one‟s family and children. Thrift is a well known Hakka virtue. But you need to know why and how to be thrifty. The „why‟ is for loving the family and children. The „how‟ is to do a better job in financial management. That is also what my business all about.”

“Revenue generation is an important part of financial

management. The Buddha tells us that the more you give, the more you receive. Money spent in giving or charity

is mostly tax-deductible. But there is more to such acts, particularly if you are taking the aforementioned „love‟ perspective. You generate and accumulate blessings for your children and family through the act of generous giving, the giving for good causes.”

“We help clients save taxes. But everything has to be done legally. The Buddha teaches us (in the Keyura Sutra 瓔珞經) that we should never ever cheat on taxes.

That is also one way (out of four) to pay back the benevolence of the nation (i.e., government) – another important teaching by the

Buddha.”

***

for new settlements. I do believe my designs reflect such traits and values.”

“I am not a devoted Buddhist, neither am I well-versed in Buddhist literature. But I am impressed by the open-mindedness of my Buddhist friends. I also learned this from my Buddhist relatives when I was young. To some extent, I have been influenced by such attitude. This is also compatible with my risk-taking mentality. I am always open to bold design. I am always willing to try out new ideas.”

***

“The Hakka traits play an important role in my career. I have only junior high school education. I started my career as an apprentice in a mechanical shop. In

addition to working hard in learning the skills, I was responsible for numerous chores, running errands, etc. As I look back, I am surprised that back then I never shed a tear no matter how tough the situations were and no matter how homesick I was. I was a man when I was just fifteen. Indeed, thrift, hard work and hard neck are the Hakka traits. I am proud to say that “I have them all!” That prepared me for taking challenges when opportunities knock.”

“I started my own business in lumber and building supplies. Actually it was not the business I started. I worked for this company which has several branches in Taiwan. When the boss was looking for someone to take the place of his son in Tainan branch, I was his top choice because he was impressed by my hardworking and honest. Later I bought this branch office and became independent. In life or in our careers, you often need someone, powerful people or guarding angels, to lend you a hand. But you must prepare yourself for taking advantage of such help or opportunities.”

“Later I got out of the lumber business and started

making lighting systems for recreation vehicles. Certainly, the major market for such products is in the U.S. When the financial crisis hit the U.S. economy, the market shrinks substantially. You bet we were prepared to find new products and new markets even before the economic downturn. We got into manufacturing of other car parts such as luggage racks, etc. We

also moved into making sirens for police cars and emergency vehicles. You should always look for new opportunities long before your business goes bad. You can always find your niche. You don‟t have to, perhaps you should not, chase after fads. See, by doing so,our business did not suffer much during the economic downturns. We did not follow many people‟s step to move operations to China. We don‟t have the need to do this. It‟s more important to find the niche, to find new products and new markets, rather than to look for the advantage of cheap labors. In fact, nowadays, the labor costs in China are not much cheaper than those in Taiwan. We kept our quality workers for years. Quality workers are more valuable than anything else in business.”

“You may be right. My strategy may be a good model for most industries in Taiwan. We don‟t have to be big companies. Just find the niche. You can always find the niche. You do not have to chase after fad. You do not need to compete with mega companies head on. We can conserve our resources and still do business in the world. People may consider me too conservative. Of course, I am conservative. You may not believe this. I have been in business for over thirty years. But I have never borrowed one penny from banks. Most people believe in using other people‟s money to make

may suggest that I can borrow money to expand my business. That may be true. But I don‟t want to lose sleep or even lose my business after I expand and the economy goes south. I don‟t have to worry about my employees might lose their jobs because of my bold

expansions. As long as you find the niche, you do not need to be a big company.”

“We take good care of our employees not because we fear that we might lose them. We simply treat them like family members. We have quite a few who have stayed with us since I started my business. Even for the new comers, we treat them with the same care and love. We try not to hire graduates from big name schools. We probably would not hire you guys from National Taiwan University. The graduates

from big name schools are usually looking for big companies for big paychecks anyway. Once they got into a big company, they became specialists in narrow fields. (Yes, you are right. An expert or a specialist is someone knows more and more about less and less). When big companies need to lay off people, these specialists may have hard time finding a new job. Our new hires tend to be more willing to learn different skills. If they need to move on to other companies, they have the capabilities to do so.

Well, we do not lay off people that often, not even during the economic downturns. Like I said, we try to treat them as family members and take care of them. I am not saying that I am a saint or sage. But when I look for new products, new markets, or new opportunities, I do not put profit as my first priority. What in my mind is usually that I am looking for ways to keep my employees, to look after them, etc. They have families to take care. They have their careers too.”

***

am not a devoted Buddhist, I have been influenced by my parents‟ religions. Well, strictly speaking, they were not „pure‟ Buddhists. They mixed Buddhism with folk religions. But they did instill in me

many of the Buddha‟s teachings. The law of cause and effect is probably the most appropriate description of my career. I was quite successful in my limousine service business. But greed got into me. I could not resist the temptation of making more money when I was invited as a partner to invest in China. I could not resist the sweet talks. I trusted people too easily, almost a blind trust. I would not blame that as a Hakka personality. But we Hakka people tend to be simple, if not

naïve, in terms of human relations. I pay the price for my greed.” “On the positive side, the Buddhist teachings helped me getting through the down period. Ah, how I wish I had remember even a little bit of the Buddhist teachings when I was at the peak of my business. Endurance and patience carried me through. I came back home literally penniless. Fortunately, my parents left me a small piece of land. Now I am happy to be a farmer, well, learning to be a farmer.”

***

“Although this is a Buddhist organization, we are still human. The best advice still comes from the Buddha. Patience is the best and perhaps the only way in dealing with business. We are a nonprofit organization in which human relations can be a substantial part of the

business. We need to mobilize people from time to time. Even though

the Buddha preaches compassion, we should not expect everyone showing the same amount of compassion, at least not at this stage of our cultivation. Nonprofit

“Certainly we cannot claim that Hakka people are more compassionate or kinder than other ethnic groups. But generally speaking Hakka people are kind and compassionate indeed.”

***

“You bet I treat all my employees as family members, whether they are Hakka or non-Hakka. Don‟t you think that we Hakka people are always nice to people? I try to share my wealth with my

employees as much as possible through good pays and excellent fringe benefits. After all, they are the ones who create the wealth for me. I do so not that I want them to be nice to me or to be thankful to me. But I firmly believe in the Law of Cause and Effect. One year during the economic downturn, the company ran into deep financial trouble. I insisted to keep all employees on job even though there was really not much job due to lack of business. I was deeply moved by their understanding of the company‟s condition. Many of them even offered to take voluntary pay cuts. I would never go for that. I am a „typical hard-neck Hakka‟. I can „swallow anything‟. I accepted their good-will, but not their offer. Fortunately, pretty soon, the business turned around. We survived. The Law of Cause and Effect is at work again.”

***

“I like the idea that emptiness does not the same as nothing; rather, it means

mind. What we need is indeed the empty mind, not the focused mind.”

***

“Although having two years of graduate education in the U.S. and some American work experiences, I consider myself a „true Taiwanese‟ with a deep root in traditional Hakka values. Central to my management philosophy is to treat all employees equal. My parents raised me to be kind and considerate to others. So I try to treat every employee like just another family member. I even provided financial support to one employee for completing his graduate degree and encouraged him to seek a „better‟ job elsewhere. During the weekly meetings, I often emphasized the concept of treating the whole business as a family and thus created an

atmosphere in which colleagues would earnestly help out each other. Consequently, all employees felt that they were not only a team, but also a family.”

***

“I came from a relatively poor family. Growing up, I learned how to be thrifty, but not unreasonably thrifty. My mother used to go door to door to sell bananas and guava fruits. Each evening, even though she was tired, she would carefully count how much money she made. We would suggest her take a rest instead of counting those nickels and dimes. After all, she usually did not make much money. She would insistently say, „Yes, I would count each nickel and dime because each nickel and dime counts. Save nickels and dimes now; a lot of businesses need you to invest in the future.‟ So, I would be very careful with money management. Thrifty but not stingy.”

***

feel. You will be amazed how smart customers are.”

“Yes, thrift is a well-know Hakka value. However, in restaurant business, you should not be thrifty at the expense of food quality. If you do not throw away anything

which is not fresh, just for the sake of thrift, you are fooling yourself. Your business will suffer because customers can easily tell the quality difference.”

***

“I like your process-oriented philosophy. They are quite consistent with the Buddhist teachings and with the Hakka values. The Buddha teaches us to focus on „here and now‟. In a sense, that means the focus on the process, rather than the product or the result. Results are always illusive. To be exact, even the processes are illusive because they are always transient. The third premise is particularly appropriate in change management. Over the years, I have witnessed changes in people, in working environment, in the ways people do business, etc. I guess the best strategy is like what the Buddha teaches us: Do not have attachment or fixation on anything. This does not mean we should not have any principle. We just have to be more flexible in seeing things. In fact, the less attachment or fixation we have, the

clearer we can see things. I believe your process-oriented philosophy is quite consistent with the Buddha‟s teachings.”

[The process-oriented philosophy was developed as a

management philosophy. But it is definitely applicable to our daily life, work, and career. The three premises of this philosophy are: (1) The process is usually more enjoyable than the product; (2) Take care of the process, the product will take care of itself; and (3) Any

product is only part of an endless process. For details, see Chung (1999).]

“We offer many types and many grades of tea. Different

customers may have different tastes. However, sometimes customers need to be „educated‟ to appreciate the quality of tea. The ways you prepare the tea definitely affect its taste. It also takes time to „learn‟ how to appreciate the quality of tea. I believe the same principle is applicable to any product. The Buddha has eighty-four- thousand dharma methods to teach sentient beings. I wish I have

eighty-four-thousand ways in preparing teas for customers. Or, I should take that back. Any particular customer does need