Objective: In this study, we aimed to analyze the length of stay (LOS) and di- rect medical costs (DMC) for psychogeriatric inpatients in Taiwan. Methods: We obtained the data from the Psychiatric Inpatient Medical Claim database of Tai- wan’s National Health Insurance. LOS and DMC of different mental illnesses were analyzed. Results: The average LOS of our study patients was 43.53 days, and the mean DMC was 2,576 US dollars. Dementia was the most common psychiatric di- agnosis. Average LOS and DMC were signifi cantly higher in male patients than female (p < 0.001 and p = 0.022, respectively). Over 90% of DMC were non-drug expenses (NDE). The LOS of patients with dementia and major depression was signifi cantly higher for males than for females (p < 0.001). Patients’ LOS and DMC showed differences among gender, diagnosis, and type of hospital. The LOS of dementia and delusional disorders and the DMC of major depressive disorders had heterogeneities across hospital types. The results of regression analysis indi- cated the LOS and the DMC of schizophrenic patients were signifi cantly higher than those of dementia patients (p < 0.001); the LOS of community hospitals was signifi cantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of general hospitals (medical centers and regional hospitals), with the opposite being true for DMC. Compared to public hospitals, the drug expense (DE) was signifi cantly higher in private hospitals (p <

0.04), but LOS and NDE were lower. Conclusion: The determinants affecting dif- ferences of LOS and DMC of psychogeriatric inpatients were gender, psychiatric diagnosis, and type of hospital. The DE and NDE of DMC were about 10% and 90%, respectively, but only the NDE showed signifi cant difference based on gender.

Length of Stay and Direct Medical Costs for Psychogeriatric Inpatients in Taiwan

Chin-Ming Liu, M.D.

1, 2, Chu-Shiu Li, Ph.D.

3, Chwen-Chi Liu, Ph.D.

4, Chu-Chin Tu, M.S.

2Key words: length of stay, direct medical cost, geriatrics (Taiwanese Journal of Psychiatry [Taipei] 2011; 25: 248-60)

1 Division of Psychosomatics, Cheng Ching Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan 2 Ph.D. Program in Business, Feng Chia University, Taic- hung, Taiwan 3 Department of International Business, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan 4 Department of Risk Management and Insurance, Feng Chia University, Taichung, Taiwan

Received: May 23, 2011; revised: July 18, 2011; accepted: September 15, 2011

Address correspondence to: Dr. Chin-Ming Liu, 7F, No. 221, Section 4, Qingdao Road, Beitun District, Taichung 406, Taiwan

Introduction

Length of stay (LOS) and direct medical costs (DMC) are frequently used to evaluate the healthcare effi ciency and quality as well as hospi- tal resource use [1-4]. At the stage of imbalance of Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) fi nance and reform of the NHI fi nancial system, reducing LOS and DMC for hospital inpatient care is clear- ly a powerful strategic weapon [5]. Among all kinds of diseases, the LOS and DMC of mental illnesses are especially important because of their characteristics of chronicity and diffi culty in treat- ment and restoration of social and occupational functioning. Combined with a predicted signifi - cant increase in the proportion of the elderly (aged 65 years and over) in the Taiwanese population (from 10.7% in 2010 to 41.6% in 2060), fi nancing the medical care may lead to further fi nancial dif- fi culty in the NHI system in Taiwan [5, 6].

The LOS and DMC of psychogeriatric in- patients have become important issues in Taiwan due to three major reasons: First, similar to Japan and South Korea, life expectancy is in- creasing while the growth rate of the population is declining [7]. The increasing number of the elderly often increases in medical costs. Second, LOS and DMC are key subjects for research topics since the global budget system of NHI leads to a diversity of operating strategies in different hospitals for the same disease. This implies that the LOS and DMC of psychiatric inpatients may vary among the levels of medi- cal institutions [8]. And third, different diseases vary in LOS and DMC.

The aim of this study was to examine several factors associated with the LOS and DMC for psychogeriatric inpatients in Taiwan during 2006.

We hope that the fi ndings of this study would pro-

vide an important reference for NHI planning and fi nancing.

Methods

Data source and study sample

The NHI program of Taiwan, implemented in 1995, covers health cares for over 99% of the Taiwan’s inhabitants [9]. All hospitals must pro- vide information of medical services (including patient’s gender, age, diagnosis, medicines and service fees, etc.) to claim reimbursement from the Bureau of NHI.

Extracting from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) inpatient claims data, and the Psychiatric Inpatient Medical Claim (PIMC) datasets were constructed accord- ing to patients who were admitted to the psychiat- ric department. We used the PSY2 dataset, one subset of PIMC, in the study. In that dataset, we included patients who had their fi rst psychiatric admissions between 2002 and 2007.

In the dataset, diagnoses of mental illness were coded using the International Classifi cation of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modifi cation (ICD-9-CM). Codes 290-319 indicate mental dis- orders such as dementia disorders, alcohol-related disorders, transient organic brain syndromes, or- ganic mental disorders, schizophrenic disorders, affective disorders and delusional disorders, etc.

Based on the PSY2 database, we extracted information about psychiatric inpatients such as numbers, hospitalization frequencies, demograph- ics, LOS, diagnoses, DMC, and information of health facilities such as ownership type and insti- tution type from the psychiatric service. We in- cluded 96,013 patients in PSY2. Among those pa- tients, 15,109 (16%) elder patients (age 65 years and over) were admitted to psychiatric inpatient ward in the 2002-2007 period. The annual num-

bers of psychogeriatric inpatients from 2002 to 2006 were 2,282, 2,326, 2,590, 2,722, and 2641, respectively.

To examine the common factors infl uencing psychogeriatric inpatients’ LOS and DMC, we se- lected the elderly patients who were admitted to psychiatric wards during a one-year period (January 1, 2006 - December 31, 2006). Excluded were patients who were foreigners or lacked basic information such as gender or age. We also ex- cluded patients with DMC paid after 2006, and LOS which extended beyond December 31, 2006, or LOS or DMC reported to be zero. Ultimately, we included 2,641 inpatients with 3,455 hospital- izations in this study.

Measures and variables

LOS is defi ned as the period from the date of admission to the hospital to the date of discharge (measured in days per admission). For those who had more than one admission during 2006, we took an average, where LOS was calculated as the total length of stay over the total number of hospi- talizations [1]. DMC is defi ned as a psychogeriat- ric inpatient’s hospitalization costs, such as the drug expenses, the service fees, the acute bed fees, the chronic bed fees, etc., per admission. Therefore, we divided the DMC into drug expense (DE) and non-drug expense (NDE). The DMC, DE and NDE were denominated in United States Dollars (US$1/NT$31.42). Two categories of explanatory variables existed in this study. The fi rst type was characteristics of psychogeriatric inpatients, such as gender, age and disease. The second type was referred to characteristics of health facilities. Five- year intervals were used to divide psychogeriatric inpatients into six age groups: 65-69, 70-74, 75- 79, 80-84, 85-89, and 90 years and older [10].

We used the fi rst of fi ve diagnoses (principal diagnosis) in PSY2 claims data to classify patients

into different diseases. We divided all inpatients according to their principal diagnoses in the ICD- 9-CM’s section 290-316 [11]. If patients had mul- tiple admissions with same diagnosis, then they were categorized into “one major diagnosis.” On the contrary, patients were assigned into “more than one major diagnosis,” if they had multiple admissions with different diagnoses. Patients with only one major diagnosis that is not one of the top ten were labeled as “others.” Therefore, our study had 12 diagnosis categories: 290, dementia disor- ders (included ICD-9-CM codes 331.0-331.2);

293, transient organic brain syndromes; 294, or- ganic mental disorders; 295, schizophrenic disor- ders; 296, affective disorder (divided into major depressive disorder and bipolar affective disor- der); 297, delusional disorders; 298, other non-or- ganic mental disorders; 300, anxiety disorders;

300.4, neurotic depression; 311, depressive disor- ders, NOS; others (excluding the top 10 diagno- ses); and more than one major diagnosis. The ICD-9-CM codes were added after the diagnostic terms in Tables.

Institutional characteristics were classifi ed ac- cording to type and hospital ownership. Hospitals are accredited as medical centers, regional hospi- tals, community hospitals and psychiatric hospitals every four years by Taiwan Joint Commission of Hospital Accreditation (TJCHA). In this study, however, institutions were divided into three types:

general, community, and psychiatric hospitals.

Medical centers and regional hospitals were com- bined under the general hospitals category because of their similarities in scale of services and the same level of payment by BNHI. Psychiatric hospitals were defi ned as those with beds exclusively for psychiatric patients. This condition did not exist in general hospitals or community hospitals. Basing on ownership, institutions can be classifi ed as pri- vate or public hospitals.

In our regression model, the reference groups were female, 65-69 years of age, dementia, admit- ted to general hospitals, and admitted to public hospitals.

We did not seek study approval from the in- stitutional review board from our institution be- cause the data were de-linked information pur- chased from NHIRD.

Statistical analyses

We used one-way ANOVA and t-test analy- ses to examine the relationship among LOS, DMC, DE, NDE, patient characteristics, and hos- pital characteristics. During the data processing, we found that LOS was positively skewed and DMC was so large that it biased our regression re- sults. All outcome variables, such as LOS, DMC, DE and NDE, were given a natural logarithmic transformation for statistic process that solved po- tential biases. Finally, we used zero-truncated Tobit regression analysis, to assess the correlation between explanatory and outcome variables be- cause zero or negative LOS and DMC of patients were not included in our samples.

All data of the study were computed using Statistical Analytic System (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA) software version 9.13 for Windows. The differences between the groups were considered signifi cant if p-values were smaller than 0.05.

Results

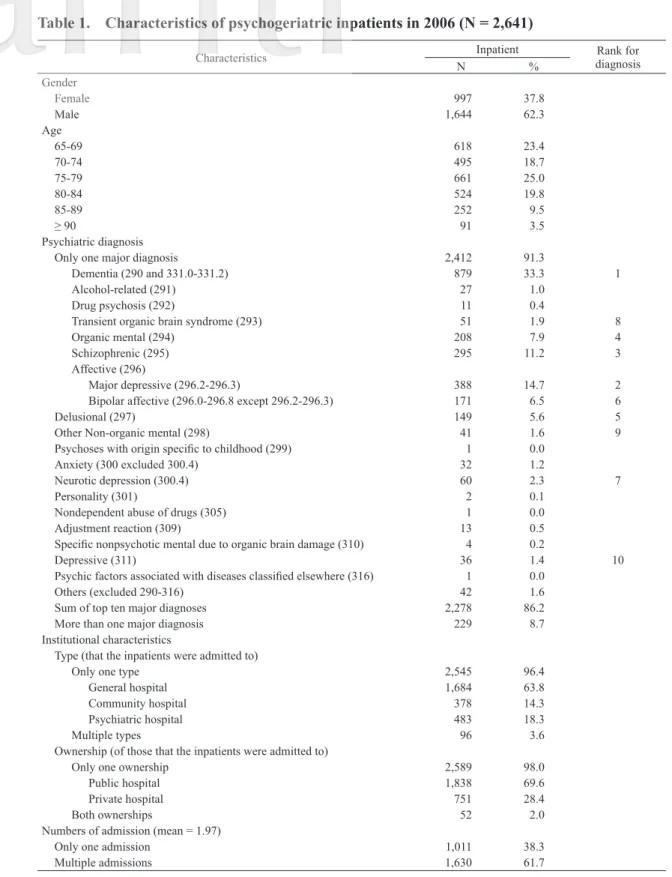

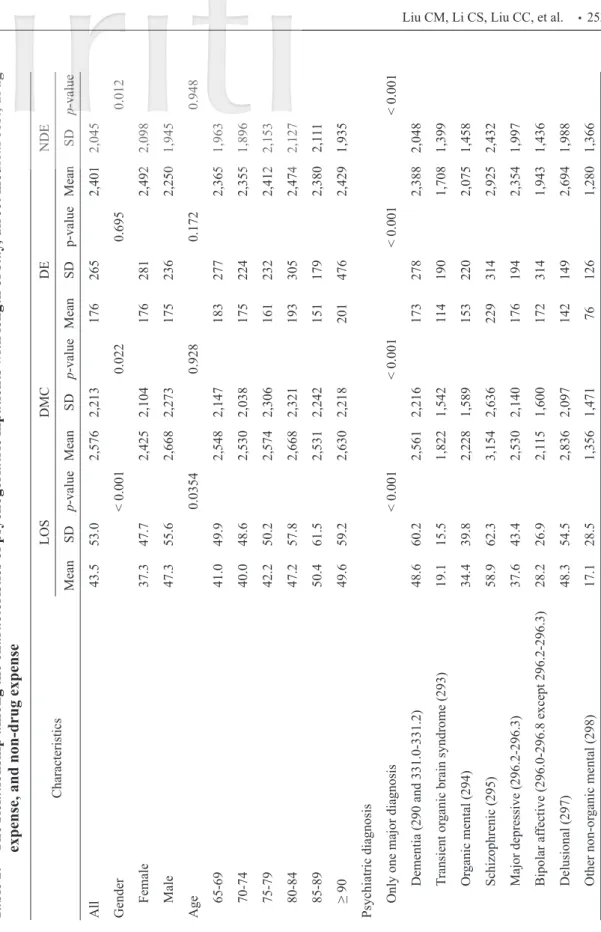

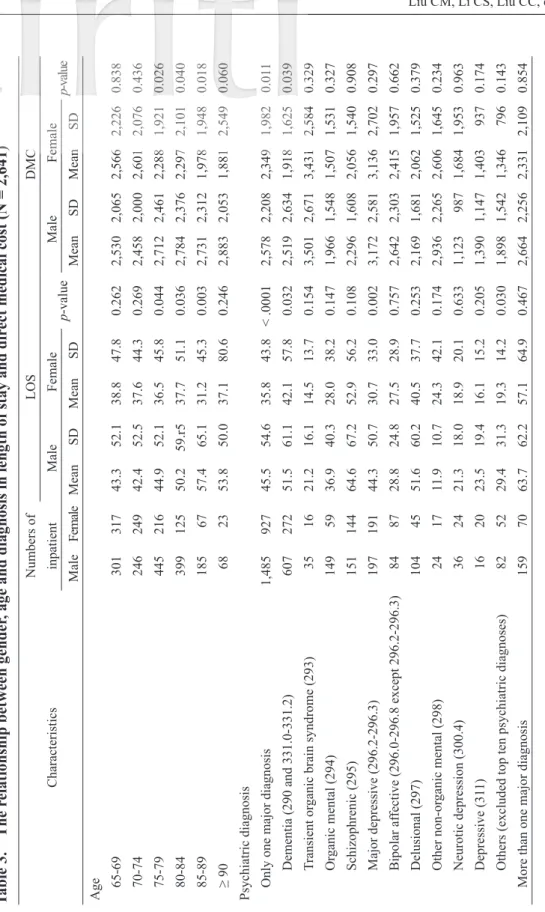

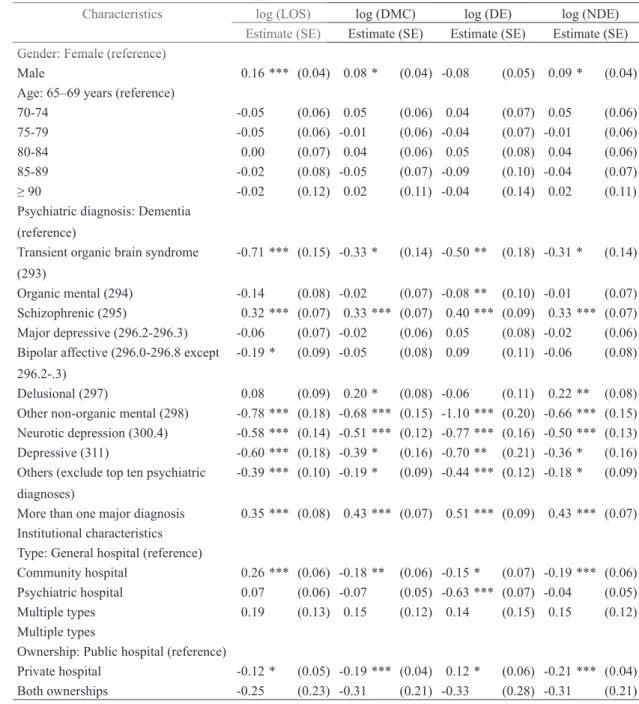

Table 1 lists characteristics of 2,641 psycho- geriatric inpatients in 2006. Table 2 shows the re- lationship among the characteristics of psychoge- riatric inpatients with length of stay, direct medical cost, drug expense and non-drug expense. Table 3 is the relationship between gender, age and diag- nosis in length of stay and direct medical cost (N

= 2,641). Table 4 illustrates the relationship be- tween types of hospitals and psychiatric diagnoses in length of stay and direct medical cost (N = 1,872). And Table 5 represents determinants of psychogeriatric inpatients for length of stay, direct medical cost, drug expense, and non-drug expense (N = 2,641).

Discussion

As shown in Table 1, we found that the gen- der ratio of the patients was predominantly male with M: F = 1.65: 1. This result was the highest one when compared to fi ndings from studies in Japan (M: F = 1.11: 1), and the ratio was reversed in the data from Shanghai (M: F = 1: 1.87), Korea (M: F = 1: 1.16), and the United States (M: F = 1:

1.43) [1-2, 12-13]. In 1949, Taiwan had the popu- lation of roughly 8 million. But at the end of the Chinese civil war, 600,000 male soldiers retreated from China to Taiwan, which led to obvious changes in Taiwan’s gender distribution pattern [14, www.aamh.edu.au]. Now those soldiers have become part of the elderly population. In addition, preference for sons in Taiwan is another important factor in the further worsening of the imbalance of the gender ratio [15].

Elderly patients’ average LOS (43.53 days) in Taiwan (Table 2) was shorter than that of elder- ly patients in Korea (128 days) and Japan (mini- mum LOS is 146 days) [1-2], but longer than that of the US (11.7 days) [16]. Compared with other countries, DMC in Taiwan (US$2,576) was lower than that of the United States (US$5,904). In addi- tion, DMC of dementic patients in Shanghai (US$708) are lower than that of Taiwan (US$2,572) [12]. The ratio of DE to NDE was reversed; DE (US$172) in our data was lower than that of Shanghai (US$653). Based on this study fi nding, we suggest that the supply of manpower in the

Table 1. Characteristics of psychogeriatric inpatients in 2006 (N = 2,641)

Characteristics Inpatient Rank for

diagnosis

N %

Gender

Female 997 37.8

Male 1,644 62.3

Age

65-69 618 23.4

70-74 495 18.7

75-79 661 25.0

80-84 524 19.8

85-89 252 9.5

≥ 90 91 3.5

Psychiatric diagnosis

Only one major diagnosis 2,412 91.3

Dementia (290 and 331.0-331.2) 879 33.3 1

Alcohol-related (291) 27 1.0

Drug psychosis (292) 11 0.4

Transient organic brain syndrome (293) 51 1.9 8

Organic mental (294) 208 7.9 4

Schizophrenic (295) 295 11.2 3

Affective (296)

Major depressive (296.2-296.3) 388 14.7 2

Bipolar affective (296.0-296.8 except 296.2-296.3) 171 6.5 6

Delusional (297) 149 5.6 5

Other Non-organic mental (298) 41 1.6 9

Psychoses with origin specifi c to childhood (299) 1 0.0

Anxiety (300 excluded 300.4) 32 1.2

Neurotic depression (300.4) 60 2.3 7

Personality (301) 2 0.1

Nondependent abuse of drugs (305) 1 0.0

Adjustment reaction (309) 13 0.5

Specifi c nonpsychotic mental due to organic brain damage (310) 4 0.2

Depressive (311) 36 1.4 10

Psychic factors associated with diseases classifi ed elsewhere (316) 1 0.0

Others (excluded 290-316) 42 1.6

Sum of top ten major diagnoses 2,278 86.2

More than one major diagnosis 229 8.7

Institutional characteristics

Type (that the inpatients were admitted to)

Only one type 2,545 96.4

General hospital 1,684 63.8

Community hospital 378 14.3

Psychiatric hospital 483 18.3

Multiple types 96 3.6

Ownership (of those that the inpatients were admitted to)

Only one ownership 2,589 98.0

Public hospital 1,838 69.6

Private hospital 751 28.4

Both ownerships 52 2.0

Numbers of admission (mean = 1.97)

Only one admission 1,011 38.3

Multiple admissions 1,630 61.7

Table 2. The Relationship among the characteristics of psychogeriatric inpatients with length of stay, direct medical cost, drug expense, and non-drug expense CharacteristicsLOSDMCDENDE MeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-value All43.553.02,5762,213176 265 2,401 2,045 Gender< 0.0010.0220.6950.012 Female37.347.72,4252,104176 281 2,492 2,098 Male47.355.62,6682,273175 236 2,250 1,945 Age 0.03540.9280.1720.948 65-6941.049.92,5482,147183 277 2,365 1,963 70-7440.048.62,5302,038175 224 2,355 1,896 75-7942.250.22,5742,306161 232 2,412 2,153 80-8447.257.82,6682,321193 305 2,474 2,127 85-8950.461.52,5312,242151 179 2,380 2,111 ≥ 9049.659.22,6302,218201 476 2,429 1,935 Psychiatric diagnosis Only one major diagnosis< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001 Dementia (290 and 331.0-331.2)48.660.22,5612,216173 278 2,388 2,048 Transient organic brain syndrome (293)19.115.51,8221,542114 190 1,708 1,399 Organic mental (294)34.439.82,2281,589153 220 2,075 1,458 Schizophrenic (295)58.962.33,1542,636229 314 2,925 2,432 Major depressive (296.2-296.3)37.643.42,5302,140176 194 2,354 1,997 Bipolar affective (296.0-296.8 except 296.2-296.3)28.226.92,1151,600172 314 1,943 1,436 Delusional (297)48.354.52,8362,097142 149 2,694 1,988 Other non-organic mental (298)17.128.51,3561,47176 126 1,280 1,366

CharacteristicsLOSDMCDENDE MeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-valueMeanSDp-value Neurotic depression (300.4)20.418.71,3961,05986 168 1,310 1,000 Depressive (311)19.417.31,5911,20070 59 1,522 1,166 Others (excluded top ten psychiatric diagnoses)25.526.42,2862,307173 401 2,113 1,985 More than one major diagnosis61.762.93,4802,639235 256 3,245 2,472 Institutional characteristics Type (that the inpatients were admitted to) Only one type< 0.0010.322< 0.0010.085 General hospital 38.046.52,5292,125186 273 2,343 1,946 Community hospital64.974.32,5582,334187 304 2,371 2,136 Psychiatric hospital45.553.52,7032,501125 199 2,578 2,370 Multiple types46.132.32,8311,613199 228 2,632 1,495 Ownership (of those that the inpatients were admitted to) Only one ownership0.011< 0.0010.535< 0.001 Public hospital 45.353.32,7312,309178 269 2,553 2,139 Private hospital 39.552.82,2101,944171 259 2,039 1,773 Both ownerships38.024.22,2311,077135 91 2,097 1,029 Abbreviations: LOS = length of stay, DMC = direct medical cost, DE = drug expense, NDE = non-drug expense, and SD = standard deviation Note: p-values were obtained from t-tests or one-way analyses of variance as appropriate; DMC are in U.S. dollars (US$1/NT$31.42).

(cont.)

Table 3. The relationship between gender, age and diagnosis in length of stay and direct medical cost (N = 2,641) CharacteristicsNumbers of inpatientLOSDMC MaleFemale p-valueMaleFemale p-value MaleFemaleMeanSDMeanSDMeanSDMeanSD Age 65-6930131743.352.138.847.80.2622,5302,0652,5662,2260.838 70-7424624942.452.537.644.30.2692,4582,0002,6012,0760.436 75-7944521644.952.136.545.80.0442,7122,4612,2881,9210.026 80-8439912550.259.r537.751.10.0362,7842,3762,2972,1010.040 85-891856757.465.131.245.30.0032,7312,3121,9781,9480.018 ≥ 90682353.850.037.180.60.2462,8832,0531,8812,5490.060 Psychiatric diagnosis Only one major diagnosis1,48592745.554.635.843.8< .00012,5782,2082,3491,9820.011 Dementia (290 and 331.0-331.2)60727251.561.142.157.80.0322,5192,6341,9181,6250.039 Transient organic brain syndrome (293)351621.216.114.513.70.1543,5012,6713,4312,5840.329 Organic mental (294)1495936.940.328.038.20.1471,9661,5481,5071,5310.327 Schizophrenic (295)15114464.667.252.956.20.1082,2961,6082,0561,5400.908 Major depressive (296.2-296.3)19719144.350.730.733.00.0023,1722,5813,1362,7020.297 Bipolar affective (296.0-296.8 except 296.2-296.3)848728.824.827.528.90.7572,6422,3032,4151,9570.662 Delusional (297)1044551.660.240.537.70.2532,1691,6812,0621,5250.379 Other non-organic mental (298)241711.910.724.342.10.1742,9362,2652,6061,6450.234 Neurotic depression (300.4)362421.318.018.920.10.6331,1239871,6841,9530.963 Depressive (311)162023.519.416.115.20.2051,3901,1471,4039370.174 Others (excluded top ten psychiatric diagnoses)825229.431.319.314.20.0301,8981,5421,3467960.143 More than one major diagnosis1597063.762.257.164.90.4672,6642,2562,3312,1090.854 Abbreviations: LOS = length of stay, DMC = direct medical cost, and SD = standard deviation Note: p-values were obtained from t-tests or one-way analyses of variance as appropriate; DMC are in U.S. dollars (US$1/NT$31.42).

fi eld of psychogeriatric care in Taiwan was more suffi cient than that in Shanghai.

The higher LOS and DMC in male compared to female inpatients might be caused by a patriar- chal culture, shame and negative attitudes toward mental illnesses [17], the more aggressive behav- ioral symptoms of males [18], and less adherence to treatment among males [19, 20]. In Korea, LOS is consistent with our study fi ndings of being higher among males than among females [1].

As shown in Table 2, our study result showed a signifi cant difference in LOS among age groups (p = 0.035). This fi nding is similar to that in Korea [1]. But differences among age groups in this study were not found signifi cant in DMC (Table 2).

Further indicated in Table 2, the clinical and symptomatic courses of dementia disorders,

schizophrenic disorders, and delusional disorders in psychogeriatric inpatients were longer than those in other disorders such as transient organic brain syndromes, other non-organic mental, anxi- ety, and depressive disorders (NOS). Longer treat- ment programs were needed, and more staff and facility resources were used for dementia, schizo- phrenic, and delusional disorders, thus leading to longer LOS and higher DMC, especially for the part of NDE (Table 2).

Based on the fi ndings of our study, we found that longer LOS was associated with higher DMC (Table 2). In this study (Table 5), community hos- pitals were found to have signifi cantly higher LOS than that in general hospitals (p < 0.001). Again, this study fi nding is also true in Korea [1]. But the results were not found to be signifi cantly different for DMC in this study because a comparison of Table 4. The relationship between types of hospitals and psychiatric diagnoses in length of

stay and direct medical cost (N = 1,872*) Panel A: LOS

Diagnosis/Hospital type All hospitals

General hospital (N = 1,273)

Community hospital (N = 334)

Psychiatric hospital (N = 403)

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD p-value

Dementia (290) (N = 858) 48.7 60.7 45.5 48.9 38.2 48.6 31.0 35.5 < 0.001 Organic mental (294) (N = 203) 33.8 39.6 65.9 77.2 63.2 62.2 53.1 56.9 0.225 Schizophrenic (296) (N = 282) 58.8 63.2 45.7 58.4 38.6 51.9 36.1 39.9 0.319 Major depressive (296.2-296.3) (N = 382) 37.4 43.6 75.8 81.9 42.5 45.3 40.7 42.7 0.377 Delusional (297) (N = 147) 48.1 54.7 71.0 77.6 44.7 53.4 42.6 54.7 0.009 Panel B: DMC

Dementia (290) (N = 858) 2,551 2,228 2,589 2,395 2,634 2,426 2,512 2,104 0.801 Organic mental (294) (N = 203) 2,197 1,566 2,398 1,632 2,135 1,822 2,184 1,499 0.816 Schizophrenic (296) (N = 282) 3,158 2,676 2,853 2,574 3,341 2,840 3,176 2,622 0.559 Major depressive (296.2-296.3) (N = 382) 2,519 2,144 1,569 1,702 2,608 2,528 2,650 2,129 0.006 Delusional (297) (N = 147) 2,804 2,054 2,974 2,271 2,558 1,852 2,874 2,089 0.644 Abbreviations: LOS = length of stay, DMC = direct medical cost, and SD = standard deviation

Note: p-values were obtained from one-way analyses of variance. DMC are in U.S. dollars (US$1/NT$31.42).

* Included in our cross analyses, each psychogeriatric inpatient had only one of the top fi ve psychiatric diagnoses and was admitted to only one type of institution.

Table 5. Determinants of psychogeriatric inpatients for log(length of stay), log(direct medical cost), log(drug expense), and log(non-drug expense) (N = 2,641)

Characteristics log (LOS) log (DMC) log (DE) log (NDE)

Estimate (SE) Estimate (SE) Estimate (SE) Estimate (SE) Gender: Female (reference)

Male 0.16 *** (0.04) 0.08 * (0.04) -0.08 (0.05) 0.09 * (0.04)

Age: 65–69 years (reference)

70-74 -0.05 (0.06) 0.05 (0.06) 0.04 (0.07) 0.05 (0.06)

75-79 -0.05 (0.06) -0.01 (0.06) -0.04 (0.07) -0.01 (0.06)

80-84 0.00 (0.07) 0.04 (0.06) 0.05 (0.08) 0.04 (0.06)

85-89 -0.02 (0.08) -0.05 (0.07) -0.09 (0.10) -0.04 (0.07)

≥ 90 -0.02 (0.12) 0.02 (0.11) -0.04 (0.14) 0.02 (0.11)

Psychiatric diagnosis: Dementia (reference)

Transient organic brain syndrome (293)

-0.71 *** (0.15) -0.33 * (0.14) -0.50 ** (0.18) -0.31 * (0.14)

Organic mental (294) -0.14 (0.08) -0.02 (0.07) -0.08 ** (0.10) -0.01 (0.07) Schizophrenic (295) 0.32 *** (0.07) 0.33 *** (0.07) 0.40 *** (0.09) 0.33 *** (0.07) Major depressive (296.2-296.3) -0.06 (0.07) -0.02 (0.06) 0.05 (0.08) -0.02 (0.06) Bipolar affective (296.0-296.8 except

296.2-.3)

-0.19 * (0.09) -0.05 (0.08) 0.09 (0.11) -0.06 (0.08)

Delusional (297) 0.08 (0.09) 0.20 * (0.08) -0.06 (0.11) 0.22 ** (0.08)

Other non-organic mental (298) -0.78 *** (0.18) -0.68 *** (0.15) -1.10 *** (0.20) -0.66 *** (0.15) Neurotic depression (300.4) -0.58 *** (0.14) -0.51 *** (0.12) -0.77 *** (0.16) -0.50 *** (0.13) Depressive (311) -0.60 *** (0.18) -0.39 * (0.16) -0.70 ** (0.21) -0.36 * (0.16) Others (exclude top ten psychiatric

diagnoses)

-0.39 *** (0.10) -0.19 * (0.09) -0.44 *** (0.12) -0.18 * (0.09)

More than one major diagnosis 0.35 *** (0.08) 0.43 *** (0.07) 0.51 *** (0.09) 0.43 *** (0.07) Institutional characteristics

Type: General hospital (reference)

Community hospital 0.26 *** (0.06) -0.18 ** (0.06) -0.15 * (0.07) -0.19 *** (0.06) Psychiatric hospital 0.07 (0.06) -0.07 (0.05) -0.63 *** (0.07) -0.04 (0.05)

Multiple types 0.19 (0.13) 0.15 (0.12) 0.14 (0.15) 0.15 (0.12)

Multiple types

Ownership: Public hospital (reference)

Private hospital -0.12 * (0.05) -0.19 *** (0.04) 0.12 * (0.06) -0.21 *** (0.04)

Both ownerships -0.25 (0.23) -0.31 (0.21) -0.33 (0.28) -0.31 (0.21)

Abbreviations: log(LOS) = log-transformed length of stay; log(DMC) = log-transformed direct medical costs; SE = stan- dard error.

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

general and psychiatric hospitals yielded no sig- nifi cant differences in LOS or DMC (Table 5).

Three major reasons accounted for the differences of LOS among three levels of hospitals: First, the different LOS control policies have been used by top hospital administrators. Second, the different intensities of medical and paramedical profes- sional manpower (minimal human resource stan- dards set by TJCHA) have been set differently among general, psychiatric, and community hos- pitals, which resulted in producing dissimilar LOS in different kinds of hospitals. This fi nding refl ects the issue of healthcare manpower supply. And third, hospitals’ strategic considerations were di- rected at fi nancial goal attainment [21].

Under DMC, the DE value of psychiatric hospitals was found to be signifi cantly different than that of general and community hospitals (p <

0.001, Table 2). Although the DE and DMC of general hospitals were less than those of commu- nity hospitals (186 vs. 187; 2,529 vs. 2,558), the differences were not signifi cant. But after control- ling for gender, age, diagnosis, and ownership ef- fects, the estimated results for institutional charac- teristics showed that DMC, DE, and NDE of general hospitals were signifi cantly greater than those of community hospitals (p < 0.01, Table 5).

Only DE of psychiatric hospitals was signifi cantly less than that of general hospitals (p < 0.001, Table 5). Based on those fi ndings, we suggest that the smallest DE for psychiatric hospitals is refl ecting their healthcare model being more dependent on intense manpower and medical equipment.

Comparing the operating effi ciency of public and private hospitals as revealed from results of regressions, LOS and DMC of private hospitals were signifi cantly lower than those of public ones.

When breaking down DMC into DE and NDE, DE of private hospitals was indeed higher than that of public hospitals, but NDE, including per-

sonal use, of private hospitals was lower. In Korea, LOS in private hospitals is lower than LOS in public hospitals, indicating greater operating effi - ciency in private hospitals.

Limitations of the study

The readers are cautioned against over-inter- preting the study data because this study has four major limitations. First, we focused on patients who were admitted and were discharged only in 2006. We excluded the patients who were not dis- charged in 2006 from our study. Therefore, LOS and DMC in this study could be underestimated.

In addition, based on the data of PSY2, we did not include the patients who were admitted to the psy- chiatric ward before 2002 and who were also ad- mitted to the psychiatric ward in 2006. Second, the NHIRD data of Taiwan’s NHI program do not have specifi c clinical individual information to defi nitively analyze the causal relationship of eti- ologies of admissions and treatment outcomes.

Third, as most psychiatrists in Taiwan adopted DSM-IV diagnostic criteria rather than the ICD-9 system to evaluate their patients, some gaps exist in diagnostic accuracy. And fi nally, because of the complexity of cost measurement, we only divided DMC into DE and NDE for comparison, and we did not do detailed differential evaluation (e.g., the composite of NDE such as manpower fee, clinical laboratory cost, and brain imaging cost, etc.).

Implications of the study

Three major implications exist from this study. First, the elderly people in the population is increasing, the total numbers of psychogeriatric patients are growing rapidly. The issues of LOS and DMC for psychogeriatric patients have be- come increasingly important. Previous Taiwanese studies focusing on LOS and DMC have been lim-

ited to mental illnesses. In a 2003 study of schizo- phrenia by Yeh et al., the values for LOS (40 days) and DMC (US$2,040) are lower than those ob- tained in our study results [22]. Chan et al. in 2009 studied the DMC of Alzheimer’s disease between 2000 and 2002 and found that the total DMC is increased annually [3]. But in this study, we fo- cused on all psychiatric disorders of geriatric in- patients, rather than only 1 or 2 types of mental illnesses. We thoroughly examined LOS and DMC for psychogeriatric inpatients to discover the de- termining factors that cause them.

Second, the classifi cations of mental disor- ders are also important determinants of LOS and DMC. The heterogeneities and complexities among geriatric mental disorders lead to different levels of healthcare use. The diagnoses of demen- tia, organic mental, schizophrenic, and major de- pressive disorders make up to 65% of the study population. Furthermore, LOS and DMC of de- mentia, schizophrenic, and delusional disorders are longer and higher than for other mental disor- ders. Therefore, mental healthcare teams should develop more cost-effective treatments to cope with the demands of these patients.

Finally, for managerial implication, the type of institution also plays an important role in deter- mining inpatient LOS and DMC. The characteris- tics of institutions vary among general hospitals, community hospitals and psychiatric hospitals [15]. Therefore, different levels of institutions need to use dissimilar strategies for economic pur- suit through the control of LOS and DMC.

Conclusion

In spite of four limitations in this study, we would like to conclude that gender, psychiatric di- agnoses, and types of hospital determined differ- ences of LOS and DMC of psychogeriatric inpa- tient hospitalization. The DE and NDE of DMC

were found to account about 10% and 90%, re- spectively. But only NDE was demonstrated to have signifi cant difference based on gender.

References

1. Chung W, Oh SM, Suh T, Lee YM, Oh BH, Yoon CW: Determinants of length of stay for psychiatric inpatients: analysis of a national database covering the entire Korean elderly population. Health Pol 2010; 94: 120-8.

2. Imai H, Hosomi J, Nakao H, et al.: Characteristics of psychiatric hospitals associated with length of stay in Japan. Health Pol 2005; 74: 115-21.

3. Chan AL, Cham TM, Lin SJ: Direct medical costs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: a popu- lation-based study. Curr Ther Res Clin 2009; 70:

10-8.

4. Theurl E, Winner H: The impact of hospital fi nancing on the length of stay: evidence from Austria. Health Pol 2007; 82: 375-89.

5. Hung JH, Li C: Has cost containment after the National Health Insurance system been successful?

determinants of Taiwan hospital costs. Health Policy 2008; 85: 321-35.

6. Population Projections for Taiwan Areas: 2008-2056.

Council for Economic Planning and Development, Executive Yuan, Taiwan; 2010.

7. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Paris: OECD Health Data, 2008.

8. Wang KI, Cheng SH: The analysis of level of outpa- tient visits and healthcare utilization: a before and af- ter observation of the SARS outbreak. Taiwan Journal of Public Health (Taipei) 2006; 25: 75-82.

9. Bureau of National Health Insurance. Statistic Annual Report; 2011.

10. Chung W, Cho WH, Yoon CW: The infl uence of in- stitutional characteristics on length of stay for psy- chiatric patients: a national database study in South Korea. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 1137-44.

11. Chien IC, Chou YJ, Lin CH, Bih SH, Chou P:

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among National

Health Insurance enrollees in Taiwan. Psychiatr Serv 2004; 55: 691-7.

12. Wang G, Cheng Q, Zhang S, et al.: Economic impact of dementia in developing countries: an evaluation of Alzheimer-type dementia in Shanghai, China. J Alzheimers Dis 2008; 15: 109-15.

13. Blank K, Hixon L, Gruman C, Robison J, Hickey G, Schwardz HI: Determinants of geropsychiatric inpa- tient length of stay. Psychiatr Quart 2005; 76:

195-212.

14. Lin TF: 1949 Great Retreat. Taipei: Linking Publications; 2009: 323-36.

15. Lin MJ, Luoh MC: Can Hepatitis B mothers account for the number of missing women? Evidence from three million newborns in Taiwan. Am Econ Rev 2008; 98: 2259-73.

16. Akincigil A, Hoover DR, Walkup JT, et al.:

Hospitalization for psychiatric illness among com- munity-dwelling elderly persons in 1992 and 2002.

Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59: 1046-8.

17. Chong SA, Verma S, Vaingankar JA, Chan YH, Wong LY, Heng BH: Perception of the public towards

the mentally ill in developed Asian country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007; 42: 734-9.

18. Grassi L, Biancosino B, Marmai L, et al.: Violence in psychiatric units: a 7-year Italian study of persistent- ly assaultive patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006; 41: 698-703.

19. Nosé M, Barbui C, Tansella M: How often do pa- tients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment pro- grammes? a systemic review. Psychol Med 2003; 33:

1149-60.

20. Sellwood W, Tarrier N: Demographic factors associ- ated with extreme non-compliance in schizophrenia.

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1994; 29:

172-7.

21. Su CB, TG Peng, JH Teng: The relationship between resource advantage, strategic advantage, and perfor- mance under the department of health. Journal of Healthcare Management 2001; 2: 93-109.

22. Yeh LL, Lan CF, JS Cheng: The utilization and ex- penditure of psychiatric services for patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Taiwan Journal of Public Health (Taipei) 2003; 22: 194-203.