行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

臺灣貧窮與社會排除測量指標之發展歷程研究 研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 98-2410-H-468-020-

執 行 期 間 : 98 年 08 月 01 日至 99 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 亞洲大學社會工作學系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 劉鶴群

計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:林士傑 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳芝瑜

公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 99 年 10 月 31 日

目錄

1. 前言Introduction 2

2. 文獻探討Literature Review: The Concept and Measurement of

Social Exclusion 2

3. 研究方法Research Methodology: Focus Groups 4

4. 研究發現Research Findings 6

5. 討論Discussion: Characteristics of Taiwanese Public’ s Perception

of Social Exclusion 11

6. 計畫成果自評 15

1. 前言Introduction

The concept of social exclusion has gained in much popularity in the academia in Taiwan. It is sometimes believed more appropriate to interpret the experience of the less well-offthan the“old”conceptofpoverty.To many,poverty seemsto mean a minority living under a strict poverty threshold, in a jobless household and trapped in a cycle of poverty. Social exclusion, on the other hand, is not only related to material deprivation, but also to otherfacetsofpeople’slives,such as unemployment, ill health, a lack of social network and social support, and poor local services, etc. These disadvantages are likely to be encountered by the majority of the population and hence arebelieved asabetterconceptto representthe“old poor”,aswellasthe“new poor”and the“nearpoor”.

However, as many social concepts, social exclusion is largely a European one, rooted in a European social and political context. In Taiwan, while the multi-dimensional aspects of social exclusion are widely cited and applied in the interpretation and explanation of a Taiwanese reality, little effort has been made to realise what implications can been drawn from these studies.

Starting with a brief discussion on the concept and measurement of social exclusion, this study aims to investigate how the Taiwanese public perceives the phenomenon and the concept of social exclusion and how the indicators are related to them.

2. 文獻探討Literature Review: The Concept and Measurement of Social Exclusion

Since the 1990s, a growing number of researchers and policy makers in the world have taken up the term ‘social exclusion’. Oppenheim argues that in order to clarify the term, there is a need to distinguish between poverty and social exclusion (1998). At the level of operational definition, poverty is defined by a quantifiable threshold below which one is regarded as poor. Social exclusion, on the other hand, is more complex, attempting to take full account of the processes of marginalisation from the social mainstream—which can include the labour market, family and informal networks—and from effective access to the local and national facilities of the state. Social exclusion, therefore, should be multi-dimensional, reflecting dynamic

and accumulated disadvantages on economic and non-economic aspects of people’s life, with no clear-cut point identifying who is poor.

The concepts of social exclusion have been firmly entrenched in EU government policies, as well as in important international organisations, such as the International Labour Organistaion, the United Nations, and the World Bank. However, even within a European context, the meanings attached to social exclusion vary between and within countries. Typologies developed by Hilary Silver and more recently by Ruth Levitas help make sense of its multiple meanings. Silver identifies three paradigms, labelled “solidarity”, “specialization”and “monopoly”paradigms, each of which

“attributes exclusion to a different cause and is grounded in a different political philosophy: Republicanism, liberalism and social democracy”(1994: 539). The

“solidarity”paradigm originates in France and is concerned with the breakdown in the bonds of solidarity between individual and society. “Specialization” paradigm understands social exclusion as a consequence “of social differentiation, the economic division of labour and the separation of spheres”(Silver, 1994: 542). Social exclusion results from market failure, discrimination or unenforced rights. Greater emphasis is placed on individual responsibility. The “monopoly”paradigm claims that “exclusion arises from the interplay of class, status, and political power and serves the interests of the included”(Silver, 1994: 543). Social exclusion is combated through the extension of full citizenship.

Levitas (1998, 2006) analyses how the concept of social exclusion has been deployed in terms of a set of discourses, namely the redistributive egalitarian discourse (RED), the moralistic underclass discourse (MUD), and the social integrationist discourse (SID). RED embraces notions of citizenship, social rights and social justice. MUD is frequently articulated through the language of “underclass”and

“dependency culture”to portray those excluded as culturally distinct from mainstream society. SID is preoccupied with social cohesion and, in relation to policy, is focused primarily on exclusion from paid work. Levitas sums up the differences between the three discourses according to what the excluded are seen as lacking, namely “money and resources”in RED, morals in MUD and work in SID (1998, 2006).

Silver indicates that social exclusion is embedded in the three social and political paradigms and Levitas emphasises that social exclusion is a concept to describe and explain reality rather than reality itself. Social exclusion, therefore, is to be understood as a normative concept, having significant social and political implications and being linked to government policies. At the EU and UK policy levels, the SID and

RED discourses dominates the development of modes of measurement to monitor the progress of the anti-exclusion/inclusion policies. The EU indicators of social exclusion, organised in two tiers/levels of primary and secondary measures, relating to income, labour-market position, health status and education attainment, are very much SID/RED measures (Social Protection Committee, 2001; Atkinson et al, 2002 ).

Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey in Britain (PSE) is another attempt to operationalise social exclusion empirically. In addition to exclusion from an adequate income or resources, social exclusion is divided in the PSE into three categories:

exclusion from the labour market, from services, and from social relations (including exclusion from common social activities, social networks, social support, and civic participation) (Gordon et al, 2000). The PSE reflects the RED discourse in that it incorporates the full idea of participatory citizenship in the design of the questionnaire.

In Taiwan, issues concerning social exclusion are of increasing importance in the academic circle. Lee’s study (2007), based on the conceptual work of social exclusion in the West, constructs six aspects of social exclusion and uses the Database of Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) of 2002 to investigate the disadvantages: low income, unemployment, lack of social interaction, inactive political participation, lack of social-support relationship and ill health. However, as TSCS was not initially designed to operationalise social exclusion, Lee (ibid.) admitted the data generated from the questionnaire (of TSCS) were insufficient to investigate the complicated and multi-dimensional aspects of social exclusion. Moreover, since social exclusion is not a grass-roots terminology and the Left-Right debates appear to have little impact on the policy-making in Taiwan, the concept of “social exclusion”seems difficult to overstride the academia.

3. 研究方法 Research Methodology: Focus Groups

This study aims to investigate how the Taiwanese public perceives the phenomenon and concept of social exclusion and how the indicators are related to them. The focus group method is particularly useful in that it offers the researchers an opportunity to study the views in which individuals collectively make sense of the concepts of poverty and social exclusion and construct meanings around them. The focus group method is a form of group interview. It requires several participants (in addition to moderator/facilitator); there is an emphasis in the questioning on a

particular fairly tightly defined topic; and the greatest importance is placed upon interaction within the group and the joint construction of meaning (Bryman, 2008:

474). The focus group method allows participants to probe each other’s reasons for holding a certain view, and the process of arguing and challenging with each other in the groups means that the researchers may stand a better chance of ending up with more realistic accounts of what people in Taiwan think.

In this study, focus groups take place in three phases, and participants in each group (5 to 10 participants) are described in Table 1. In the first phase, two groups of scholars/experts, specialising in poverty and social research, are gathered, then presented with pre-prepared Poverty and Social Exclusion questionnaire. The questionnaire is translated from the PSE questionnaire of Britain, with minor adjustments made by the researchers. Participants are asked to share their views on the pre-prepared questionnaire and to discuss which questions included in the questionnaire should not be there and which questions not included should be there.

Prior to the second phase of the focus groups, a preliminary questionnaire is constructed, including questions that are culturally and socially relevant to a Taiwanese context and eliminating inappropriate questions.

In the second phase, area and age are two key variables in guiding the recruitment of focus groups participants. The area criterion is to ensure that differences in the circumstances of people living in urban, rural and indigenous areas can be taken into account. Once an area has been selected, participants who meet the age criterion—elderly or non-elderly—are recruited. These variables can strongly influence how well a focus group works once the participants have been selected. For instance, indigenous parents may be less willing to speak freely in the presence of urban Han Chinese, or elderly may be willing to openly express their views only in the presence of other elderly participants. In addition, another two mixed groups are gathered. The aim is to explore whether agreement could be reached among people in widely differing circumstances.

Table 1 Profile of the Focus Groups Phase 1

Expert Focus Groups

Phase 2

Public Focus Groups

Phase 3 Public Focus

Groups

Elderly Non-elderlyParent

Mixed 2

Urban 1 1 2 Urban: 1

Rural 1 1 Rural: 1

MIA* 1 1 MIA*: 1

Note: MIA denotes Mountain Indigenous Area.

The recruited participants in focus groups of phase two look at several issues, including: what they consider essential, or necessities that everyone in Taiwan should have, be able to do or have access to; what they think about exclusion of certain spheres of society and who, if anyone, is excluded. To start with, participants are asked to describe in what circumstances a person could considered excluded by the society. Then, they are given certain social spheres and asked to identify those whom they feel are excluded or unable to fully take part in this area of life. The social spheres that are discussed are: social isolation and exclusion from friends and family, neighbourhood, health, local services, finance and debts, housing and personal security and crime.

After completing Phase Two, the researcher found that the qualitative data in relation to Taiwanesepublic’sperception ofsocialexclusion isnotextensiveenough to reach a theoretical saturation, and then another three focus groups are organised.

This Phase Three focus groups take regional differences into consideration, divided into urban, rural, and indigenous village focus groups. The three groups are asked, without any prompt, to discuss what the participants think the concept of social exclusion is, and what aspects of life are related to the experience of being excluded.

These open discussions help provide information which is lacking in the more structured Phase Two groups.

4. 研究發現 Research Findings

This section begins with a discussion of the findings derived from the expert focus groups stage (phase one), before moving on to a more detailed overview of the most important themes raised in the public focus groups (phases two and three).

4.1 Expert Focus Groups Phase

In the second expert focus group, participants are asked to discuss and identify the spheres of social life related to social exclusion. Without being given any hint, the participants point out the following spheres: economic resources, employment, health, education, housing and local area, social relationship and personal security. These

social spheres identified by the group are largely overlapping with the existing western literature on social exclusion (Levitas et al., 2007: 10). However, the expert focus group reminds the researcher that the Taiwanese public might not be able to comprehend the concept of social exclusion easily, for social exclusion is completely a western concept and its importation was relatively recent.

The focus group is then asked to discuss the aspects that make up a given sphere of social exclusion, according to the order of the questionnaire. In the sphere of social support, the focus group suggests that, in addition to the situation of being ‘ill in bed’

and having ‘financial difficulty’, as outlined in the SCHQS, the quality of social support can also be evaluated by asking whether one could find help when ‘you needed someone to look after your children, an elderly person or a disabled adult you care for’. In the sphere of area deprivation, the focus group adds ‘adult industry in the neighbourhood’as a potential concern of Taiwanese households and communities; ‘a park nearby’is considered by the group as one of the essential public local services. In the section of health, whether a person with a health problem or disability is deterred from ‘managing an affair at a government organisation’and ‘using public/private transport’are added to evaluate health exclusion, while deleting ‘arranging accommodation in a hotel or boarding house’, ‘arranging insurance’and ‘using a public telephone’, activities that are not essential in Taiwanese daily life. The expert also suggests that the feeling of isolation can also occur because of one’s particular accent, education level, appearance, age and the differences in local culture. Finally, several items regarding debts are included.

4.2 Public Focus Groups

4.2.1 Necessities and Common Activities

Participants in each focus group in the Phase Two were first asked to name what they consider necessities. Food and clothing are the two aspects covered by all the focus groups. As expected, the basic or functional requirements first come to mind when asked about necessities. Every group mentioned the need for food and clothing to protect people from hunger and the sun, rain, and cold. However, the discussion on clothing was later extended to a more social level—the need for people to appear decent or respectable in their community and social network.

Generally speaking, most participants have a clear idea of acceptable housing or the ‘home environment’. The importance of having a permanent residencewas

repeatedly emphasised; it is related to a sense of security. Sufficient bedrooms and living space for family members is another key concern. Household facilities such as tap water, electricity, and gas are also considered very important for acceptable housing.

The second type of essentials covered by the focus groups is activities.

Participants were asked their opinions on which activities every adult should be able to participate in and should not have to do without. There was considerable diversity in the activities proposed. However, two broad types of activities appear to be important: personal recreation and maintaining social relationships. The focus groups added the following activities to those listed in the questionnaire: one-day domestic trip; participating in activities held by communities, institutions, or clubs; and shopping.

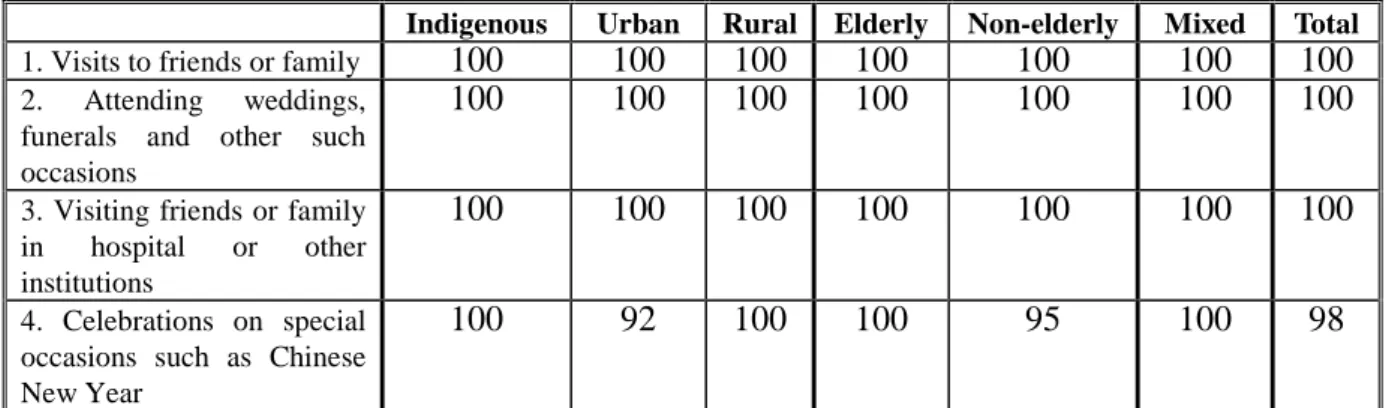

Table 2 shows that a clear majority consider activities for maintaining relationships as necessary. These include visits to friends or family; attending weddings, funerals, and other such functions; visiting friends or family in hospital or other institutions; celebrating special occasions; having a meal with visiting friends or relatives; presenting children with a red envelope at Chinese New Year; visiting places of worship; attending school; and visiting family/friends in other parts of the country on major holidays. With respect to personal recreational activities, the majority perceive hobbies or leisure activities, one-day domestic trips, and annual holidays or tours away from home as necessary activities; however, there is no consensus across groups for other such activities. For instance, while participating in activities held by communities, institutions, or clubs might be important for the elderly, the non-elderly, urban, and rural groups do not consider this important.

Similarly, there were very different responses across groups for items such as shopping, eating at a formal restaurant once a month, and visiting KTVs or Karaoke.

Table 2 Perception of Adult Common Activities (% Considered as Necessary Activity)

Indigenous Urban Rural Elderly Non-elderly Mixed Total

1. Visits to friends or family 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

2. Attending weddings, funerals and other such occasions

100 100 100 100 100 100 100

3. Visiting friends or family in hospital or other institutions

100 100 100 100 100 100 100

4. Celebrations on special occasions such as Chinese New Year

100 92 100 100 95 100 98

5. A hobby or leisure activity (e.g. sports, juggling, yoga, working out)

100 100 94 95 100 100 98

6. Having a meal with friends or relatives at home or in a restaurant when they visit

92 92 100 95 95 100 96

7. Dispensing red envelope to children at Chinese New Year

100 92 94 95 95 100 96

8. Attending temple, church, mosque, synagogue or other places of worship

100 83 94 90 95 100 94

9 Visits to school, for example, sports day, parents evening

100 83 88 100 80 100 91

10. One-day domestic trip -- 100 75 100 75 100 90

11. Visiting family/friends in other parts of the country on major holidays

100 67 75 100 60 100 83

12. Holidays or tours away from home once a year

50 83 63 65 65 100 70

1. Participating in activities held by communities, institutions, or clubs

-- 42 38 100 20 67 46

2. Shopping -- 50 25 60 23 67 46

3. A meal in a formal restaurant once a month

67 17 31 45 30 100 46

4. Going to KTV or Karaoke

75 50 13 55 30 0 37

4.2.2 Other Aspects of Social Exclusion

Having discussed the necessities and common activities, participants were asked their understanding of social exclusion and their perception of exclusion from various spheres of social life. As expected, many participants in the public focus groups had difficulty in comprehending the concept of social exclusion, because this concept is not rooted in Chinese/Taiwanese culture. However, a majority of the groups were still able to identify some social elements that could cause or prevent exclusion, for example, indifference, isolation, interpersonal relationships, violence, economic pressures, poverty, (un)employment, housing, care, love, sense of security, and health.

Below is a brief outline of the findings with respect to these spheres.

Economic/Employment

Many focus groups identify poor and/or unemployed people as excluded from society. Being employed is seen as crucial for generating enough income as well as maintaining one’sdignity.Thesocialstigma attached to unemployment and the ‘waste

of talent’associated with it were also mentioned.

Health

Being healthy and not feeling isolation are essential. The issue of access to health services is also considered to be very important. Those who have no access to a clinic or hospital or who live far away from such facilities were identified as excluded from society. The rural elderly focus group suggested that in order to promote healthy ageing, an ‘elderly day care service’must be provided. Some other focus groups expressed concern regarding the threat posed by the mentally ill in the neighbourhood, reflecting the impact of mental health issues on people’s social lives.

Access to Services

The focus groups also covered some services that they view are essential. The items proposed by almost all the groups were electricity, transport, and education.

Since education is considered a crucial route to employment, participants gave this sphere extremely high importance. Another issue worth noting is transportation. It is evident that inadequate transport facilities can exclude people from participating in various activities and become a major impediment to access to a number of important services, particularly, health and educational services. The lack of a proper public transport system makes it difficult for people to seek jobs and fulfil obligations related to their employment. The lack of access to public transport in rural and, in particular, indigenous areas and the poor quality of roads, bridges, riverbanks, and mountain slopes have been raised as a key concern.

Housing and Neighbourhood

Many participants identified those whose houses or neighbourhoods are not of acceptable standards as excluded. In some groups, people living in places that have no

‘homely feeling’are considered as excluded. Participants living in indigenous mountainous areas believe that frequent landslides, caving in of roadbeds, broken bridges, and flooding in their neighbourhood result in their exclusion from society.

The rural group pointed out issues such as air pollution, noise, heavy traffic on the main road, gas or petrol station in the neighbourhood, and the proliferation of cell phone towers and Internet cafés as their key concerns. The urban groups were particularly worried about the number of stray dogs, the threat posed by mentally ill persons, and inadequate sewage systems.

Social Relations

Several focus groups identified love and care as the two elements that prevent people from feeling excluded, whereas people experiencing isolation and indifference tend to feel excluded. All the groups mentioned family, relatives, and neighbours as important social networks. The rural elderly group was found to stress on the significance of maintaining relationships with one’s family and relatives and on gaining mutual support from them. This is rather different from the indigenous participants, who emphasised excessively on the importance of maintaining relationships with neighbours within the tribe/community.

Security/Crime

Many participants mentioned that the threat from violence or other crimes can give rise to a feeling of insecurity. In addition to common crimes such as theft, burglary, fraud, robbery, and assault, one focus group was particularly worried about being the victims of arson. These security issues highly restrict people from participating in society.

5. 討論 Discussion: Characteristics of Taiwanese Public’ s Perception of Social Exclusion

5.1 Lacking the Concept of Social Citizenship

Although most of the groups could relate many aspects of people’s life to social exclusion, it is argued that in their interpretations, the concept of social citizenship is lacking. Being excluded, for many focus groups, mainly means the inability to escape the “evils”. For instance, many urban groups mentioned that living in an area with the threat from the mentally ill is an unbearable circumstance, which is related to the feeling of being excluded. For the public, the presence of the mentally ill represents a disturbing “social problem”, deterring others from participating in the society.

Members of one focus group state:

Now many of us live in the building with the mentally ill person. It is scaring.

Yeah, we are worried about the safety. S/He has the mental illness, bipolar disorder, or depression and those who set fire are with mental illness. (cp 18)

On the other hand, indigenous people are particularly concerned with landslides, caving in of roadbeds, broken bridges, and flooding in their neighbourhood; and the rural groups stress issues such as air pollution, noise, heavy traffic on the main road,

etc. Other “

evils”the focus groups mention include poverty, unemployment, ill health, isolation and crime. An absence of the “evils”is required for not being excluded;meanwhile the public rarely clarify who should account for the existence of these problems. Should the state, the market, the volunteer sector or family be responsible?

Taiwanese public hardly ever connect these problems to the larger society or to the government. In other words, the presence of the “evils”is not considered as a violation of social rights or citizenship. It is people’s “want”rather than “right”not being excluded.

In addition, the Taiwanese public has a clear idea of what they need in order to live a decent life—having necessities, participating in common activities and having access to basic services. However, in a similar way, although the deprivation of these items leads to exclusion from the society, it is not a common thought that it is a person’s right to be guaranteed a proper standard of living.

5.2 The Division between Deserving and Undeserving Excluded

In the core of the Confucian teaching, in order to become a gentleman (君子), it is important for a person to have “good intentions toward others”(與人為善). A gentleman helps others to achieve their moral perfection, but not their evil conduct (君子成人之美,不成人之惡). Deeply influenced by this thought, Taiwanese people believe it is not morally right to exclude people, unless they do not have “good intentions toward others”.

Therefore a division between a deserving exclusion and an undeserving exclusion is made by the public. The deserving excluded generally refer to those who are disadvantaged, such as the aged, the disabled or people with a long-term illness.

The society should show sympathy to these people and help them to maintain a basic standard of living. However, there are some others who are the undeserving excluded.

Those people who are capable of working and participating in the society, but they choose not to belong to this category.

If a person could not coordinate with others, will you exclude her/him? Ah, s/he will exclude us, and of course, we will exclude her/him. This issue (exclusion) is very serious. People are too subjective and that’s why we have so many social problems around us. (sec33)

Instead of being excluded, why shouldn’t we be an accepted person? It is our personality causing the problem. If you have a strong feeling of inferiority, or you do not dare to face the reality, it will be difficult for you overcome the obstacles.

So personality matters most! (Sea 54)

Although the above discussions are regarding the concept of social exclusion, the Taiwanese public tends to focus on personality and individual value. This appears to be similar to the moralistic underclass discourse (MUD), attributing the undeserving excluded to their behaviour or their moral defects.

However, the Taiwanese public does not go so far as to suggest that there is an

“underclass”or a “dependency culture”.

5.3 Difficulty in tackling multicultural issues

It is found that the social exclusion discourses have difficulty in tackling multicultural issues. Social exclusion, for the redistributive egalitarian discourse (RED), is primarily concerned with citizenship and social rights. The social rights

“mean the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilised being according to the standards prevailing in the society”(Marshall, 1950: 10-11).

There is an oversimplified assumption in the statement that all members of a society are bound to share the same social heritage and living standards. By the same token, the social integrationist discourse (SID) stresses the prominence of integrating the marginalised citizens into the larger society. However, what if there are peoples who are not keen to be integrated or who are eager to maintain their own culture and/or lifestyles? One member of an indigenous group states:

What “society”are we taking about? We live in different societies. Although we are under the same roof the Republic of China, we indigenous people have our own society. Even though our society is small, if we have different value system then we are separated from the larger society. We often discuss who construct the (larger) society. Who determine what our society is? What is our sense of belonging? the lands? the laws? or the language? Where do we belong to, in the end? Indigenous people have a sense of drifting. The lands are ours and we speak our language. But why in the framework of the (larger) society, after these decades we still cannot find our self-identity. So what social exclusion is about?

The social exclusion discourses, either SID or RED, aim to eliminate the gap in living standards. However, there is a potential tension between this wish

and the fear that the process of inclusion will be made at the cost of challenging, or severely diluting, the core values which are the defining characteristics of particular ethnic groups. It is important to consider whether priority should be given to indigenous rights, such as the right to autonomy, to cultural integrity, and to land and sources, or to individual social rights. It is argued that, in a culturally plural society, as one is to evaluate the extent of social exclusion of a certain minority group, both a general citizenship component (individual social rights) and a differential citizenship component (group rights) must be in place.

Then the conclusion and the policy suggestions drawn from the evaluation shall not be at risk of unwanted disintegration.

References

Atkinson, T., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., and Nolan, B. (2002) Social Indicators: The

EU and Social Inclusion, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bryman, A. (2008) Social Research Methods, New York: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, D., Adelman, L., Ashworth, K., Bradshaw, J., Levitas, R., Middleton, S.

Pantazis, C., Patsios, D., Payne, S., Townsend, P. and Williams, J. (2000)

Poverty and Social Exclusion in Britain, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Lee, Y-J. (2007) Estimating the Social-Excluded Population in Taiwan, Journal of

Population Studies, 35: 75-112.

Levitas, R. (1998) The Inclusive Society?, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Levitas, R. (2006) The Concept and Measurement of Social Exclusion, in C. Pantazis, D. Gordon & R. Levitas (eds.) Poverty and Social Exclusion in Britain: The

Millennium Survey, Bristol: Policy Press.

Levitas, R, Pantazis, C, Fahmy, E, Gordon, D, Lloyd, E and Patsios, D. (2007).The

Multi-dimensional Analysis of Social Exclusion, Internal Report of Department

for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).Marshall, T. H. (1950) Citizenship and Social Class, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oppenheim, C. (1998) Introduction, in Oppenheim, C. (ed.) An Inclusive Society:

Strategies for Tackling Poverty, London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Silver, H. (1994) Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity, International Labour Review, 133(5-6): 531-78.

Social Protection Committee (2001) Report on Indicators in the Field of Poverty and

Social Exclusion, European Commission: Social Protection Committee.

6. 計畫成果自評

由本研究發展出來之論文共計五篇,發表於學術研討會:

劉鶴群(2009)貧窮與社會排除:英國經驗對我國社會排除研究與政策的啟示,

發表於「邁向融合的社會:新時代下的社會排除與社會政策回應」研討會,

2009 年 12 月國立台灣大學。

劉鶴群、張琬青、陳竹上(2010)台灣原住民族女性之貧窮與社會排除:當種族 遇到性別,發表於「台灣社會福利學會年會暨國際學術研討會:風險社會下

台灣福利社會的未來」,2010 年 5 月國立中正大學。

劉鶴群、侯念組(2010)社會排除觀點在原住民族相對弱勢處境分析上的侷限性,

將發表於「2010 年社會照顧與社會工作實務研討會」,2010 年 11 月朝陽科 技大學。

劉鶴群(2010)從臺灣的脈絡理解社會排除的概念:十三場本土焦點團體的分析,

發表於「政策學習與政策創新:構建對抗社會排除政策的新思維」研討會,

2010 年 11 月台灣大學。

另已接受預計出版之期刊論文:

劉鶴群、張琬青、陳竹上(2010)貧窮家戶中原住民族女性之社會排除經驗:以 南投縣仁愛鄉為例,東吳社會工作學報,22 期,預計 2010 年 12 月出刊。

就學術成就而論,本計劃共完成十三場焦點團體,分析社會排除概念在台灣 社會脈絡下的意義,對未來本土社會排除研究有相當參考價值。就技術創新而 論,本計劃發展出台灣第一份貧窮與社會排除的調查工具,技術創新度高。就社 會影響而論,新的社會排除測量工具如果能獲得廣泛運用,能更有效測量福利落 差及生活品質的評估,對社會的貢獻度大。

無衍生研發成果推廣資料

98 年度專題研究計畫研究成果彙整表

計畫主持人:劉鶴群 計畫編號:98-2410-H-468-020- 計畫名稱:臺灣貧窮與社會排除測量指標之發展歷程研究

量化

成果項目 實際已達成

數(被接受 或已發表)

預期總達成 數(含實際已

達成數)

本計畫實 際貢獻百

分比

單位

備 註(質 化 說 明:如 數 個 計 畫 共 同 成 果、成 果 列 為 該 期 刊 之 封 面 故 事 ...

等)

期刊論文 1 1 100%

研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100%

研討會論文 4 4 100%

論文著作 篇

專書 0 0 100%

申請中件數 0 0 100%

專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件

件數 0 0 100% 件

技術移轉

權利金 0 0 100% 千元

碩士生 2 2 100%

博士生 0 0 100%

博士後研究員 0 0 100%

國內

參與計畫人力

(本國籍)

專任助理 0 0 100%

人次

期刊論文 0 0 100%

研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100%

研討會論文 0 0 100%

論文著作 篇

專書 0 0 100% 章/本

申請中件數 0 0 100%

專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件

件數 0 0 100% 件

技術移轉

權利金 0 0 100% 千元

碩士生 0 0 100%

博士生 0 0 100%

博士後研究員 0 0 100%

國外

參與計畫人力

(外國籍)

專任助理 0 0 100%

人次

其他成果

(

無法以量化表達之成果如辦理學術活動、獲 得獎項、重要國際合 作、研究成果國際影響 力及其他協助產業技 術發展之具體效益事 項等,請以文字敘述填 列。)

1. 因本計劃而與國內外學者共同申請蔣經國國際學術交流基金會研究計畫,

「台北、北京與香港貧窮與社會排除之比較研究」。計畫主持人:劉鶴群,共同

主持人:台灣大學古允文教授、台北大學張菁芬助理教授、北京大學熊躍根副 教授、香港教育學院劉嘉慧助理教授、英國 University of Bristol 的 Professor David Gordon。惜未獲補助。

2. 擔任英國 Poverty and Social Exclusion Project 之國際顧問。

成果項目 量化 名稱或內容性質簡述

測驗工具(含質性與量性) 0

課程/模組 0

電腦及網路系統或工具 0

教材 0

舉辦之活動/競賽 0

研討會/工作坊 0

電子報、網站 0

科 教 處 計 畫 加 填 項

目 計畫成果推廣之參與(閱聽)人數 0

國科會補助專題研究計畫成果報告自評表

請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況、研究成果之學術或應用價 值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性) 、是否適 合在學術期刊發表或申請專利、主要發現或其他有關價值等,作一綜合評估。

1. 請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況作一綜合評估

■達成目標

□未達成目標(請說明,以 100 字為限)

□實驗失敗

□因故實驗中斷

□其他原因 說明:

2. 研究成果在學術期刊發表或申請專利等情形:

論文:□已發表 ■未發表之文稿 □撰寫中 □無 專利:□已獲得 □申請中 ■無

技轉:□已技轉 □洽談中 ■無 其他: (以 100 字為限)

3. 請依學術成就、技術創新、社會影響等方面,評估研究成果之學術或應用價 值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)(以 500 字為限)

由本研究發展出來之論文共計 5 篇,已發表於 2009 年國立台灣大學「邁向融合的社會:

新時代下的社會排除與社會政策回應」與 2010 年國立中正大學「風險社會下台灣福利社 會的未來」等學術研討會。另外並將在 2010 年 11 月朝陽科技大學「2010 年社會照顧與社 會工作實務研討會」及 2010 年 11 月台灣大學「政策學習與政策創新:構建對抗社會排除 政策的新思維」研討會發表相關論文。此外,由本研究衍生出的論文已獲接受於 2010 年 12 月出版於東吳社會工作學報。

1. 就學術成就而論:本計劃共完成十三場焦點團體,分析社會排除概念在台灣社會脈絡 下的意義,對未來本土社會排除研究有相當參考價值。

2. 就技術創新而論:發展出台灣第一份貧窮與社會排除的調查工具,技術創新度高。

3. 就社會影響而論:新的社會排除測量工具如果能獲得廣泛運用,能更有效測量福利落 差及生活品質的評估,對社會的貢獻度大。