The Clash of Economic Ideas interweaves the economic history of the last hundred years with the history of economic thought, examining how contrasting eco- nomic ideas have developed over time to take their present forms. It traces the connections running from historical events to debates among economists, and from the ideas of academic writers to major experiments in economic policy.

The treatment offers fresh perspectives on laissez-faire, the mixed economy, socialism, and fascism; the Roaring Twenties, business cycle theories, and the Great Depression; institutionalism and the New Deal; the Keynesian revolution;

and war, nationalization, and central planning. The work explores the post- war revival of invisible-hand ideas; economic development and growth, with special attention to contrasting policies and thought in Germany and India;

the gold standard, the interwar gold-exchange standard, the postwar Bretton Woods system, and the Great Inflation; public goods and public choice; free trade versus protectionism; and finally fiscal policy and public debt. The inves- tigation analyzes the theories of Adam Smith and earlier writers on economics when those antecedents are useful for readers.

Lawrence H. White is Professor of Economics at George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia. He previously taught at New York University, the University of Georgia, and the University of Missouri – St. Louis. Best known for his work on monetary thought and alternative monetary institutions, his books include Free Banking in Britain(2nd edition,1995), The Theory of Monetary Institutions (1999), and Competition and Currency (1989), and he has edited six other vol- umes primarily in monetary and financial history. His writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal and in leading economics journals such as American Economic Review and Journal of Economic Literature. Professor White is fea- tured in three online videos discussing the business cycle theory of F. A. Hayek, produced by www.econstories.tv in connection with their popular Keynes vs.

Hayek rap video “Fear the Boom and Bust.” He is coeditor of the online journal Econ Journal Watch and hosts the bimonthly Econ Journal Watch Audio pod- casts. Professor White received the 2008 Distinguished Scholar Award of the Association for Private Enterprise Education. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Great Policy Debates and Experiments of the Last Hundred Years

Lawrence H. wHite

George Mason University

Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press

32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107621336

© Lawrence H. White 2012

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements,

no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 2012 Printed in the United States of America

A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data White, Lawrence H. (Lawrence Henry)

The clash of economic ideas : the great policy debates and experiments of the last hundred years / Lawrence H. White.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-107-01242-4 – ISBN 978-1-107-62133-6 (pbk.) 1. Economics – History – 20th century. 2. Economics – History – 21st

century. I. Title.

HB87.W45 2012 330.1–dc23 2011049743 ISBN 978-1-107-01242-4 Hardback ISBN 978-1-107-62133-6 Paperback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication and does not

guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

v

List of Figures page vii

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction 1

1. The Turn Away from Laissez-Faire 12

2. The Bolshevik Revolution and the Socialist Calculation

Debate 32

3. The Roaring Twenties and Austrian Business Cycle Theory 68 4. The New Deal and Institutionalist Economics 99 5. The Great Depression and Keynes’s General Theory 126 6. The Second World War and Hayek’s Road to Serfdom 155 7. Postwar British Socialism and the Fabian Society 174 8. The Mont Pelerin Society and the Rebirth of Smithian

Economics 202

9. The Postwar German “Wonder Economy” and Ordoliberalism 231 10. Indian Planning and Development Economics 246 11. Bretton Woods and International Monetary Thought 275

12. The Great Inflation and Monetarism 306

13. The Growth of Government: Public Goods and Public Choice 332

14. Free Trade, Protectionism, and Trade Deficits 360 15. From Pleasant Deficit Spending to Unpleasant Sovereign

Debt Crisis 382

Index 413

vii

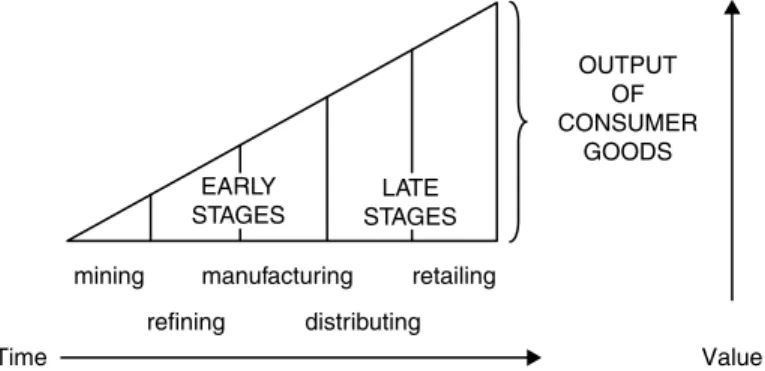

3.1. Stylized Structure of Production page 79

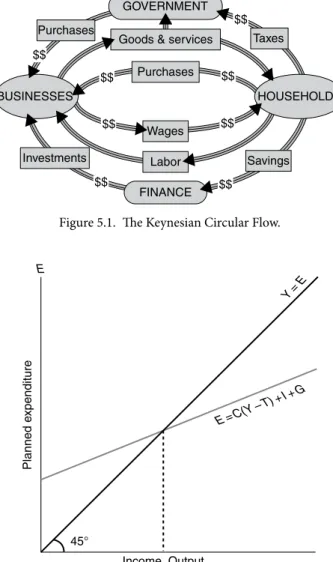

5.1. The Keynesian Circular Flow 134

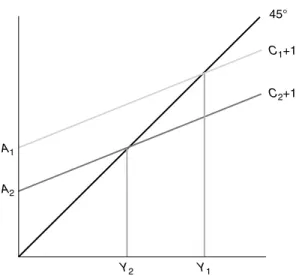

5.2. Keynesian Income-Expenditure Equilibrium 134 5.3. Reduced Consumption Spending (Falling to C2 from C1)

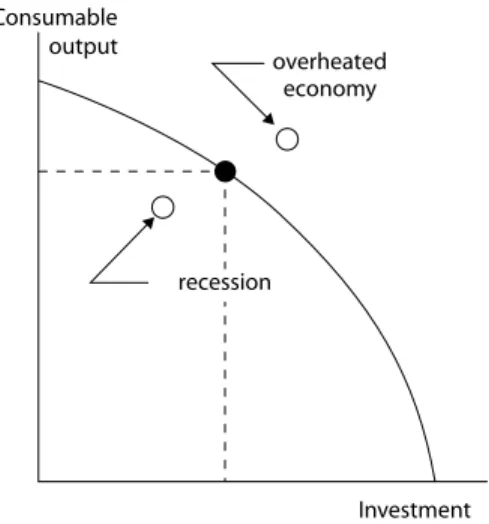

Has a Multiple Effect on Income (Which Falls to Y2 from Y1) 136 5.4. The Production Possibilities Frontier between Consumption

and Investment 138

7.1. Mr. Cube Opposes the Nationalization of Sugar Refiners

Tate and Lyle 178

12.1. Long-Run and Short-Run Phillips Curves 330

ix

My first debt is to David Rose, my former colleague and department head at the University of Missouri – St. Louis, for assigning me to teach the “History of Economic Thought” course that started me off on this project, and for cre- ating a congenial environment in which to pursue it. The Social Philosophy and Policy Center at Bowling Green State University generously gave me an office during part of the spring (so-called, in northwest Ohio) semester of 2008 where I drafted the first seven chapters. Jeff Paul, Ellen Frankel Paul, and Fred Miller of the center, and their graduate students, provided valu- able feedback. In fall 2009 I moved to George Mason University, where my new colleagues welcomed the book project and gave me many useful com- ments and references, especially Peter Boettke, Don Boudreaux, Dan Klein, David Levy, and Richard Wagner. The financial support of the Mercatus Center at George Mason has been indispensible to completing the book, and the center helpfully circulated draft chapters in their working papers series. I particularly want to thank Claire Morgan, Brian Hooks, and Tyler Cowen in connection with Mercatus’s help.

The Liberty Fund, Inc., held a very helpful Socratic Seminar around the manuscript-in-progress in May 2010. I am indebted to Chris Talley and Amy Willis of Liberty Fund for making it happen, Bruce Caldwell of Duke University for being discussion leader, and all of the participants for chal- lenging questions and helpful comments: Peter Boettke, Tawni Ferrarini, Emily Fisher Gray, Ryan P. Hanley, Bobbie Herzberg, Jeff Hummel, Nyle B. Kardatzke, Arnold Kling, Maria Pia Paganelli, Alex Potapov, Russ Sobel, and Diana Weinert Thomas. Bruce Caldwell’s students at Duke in written form and Doug Irwin’s students at Dartmouth College in person gave me useful feedback from the reader’s perspective. Along the way I presented several chapters at the annual meetings of the Association for Private Enterprise Education, and I thank those involved in organizing the

sessions, particularly Bruce Yandle and Debi Ghate. For thoughtful remarks on Chapter 3 at a New York University seminar I thank Israel Kirzner and Mario Rizzo. Dave Hakes provided helpful comments on Chapter 12 at a session of the Midwest Valley Economics Association meetings. Gurbachan Singh graciously arranged a seminar on Chapter 10 at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. I thank the following GMU graduate students for help- ful seminar discussions: Simon Bilo, Nick Curott, Harry David, Thomas Hogan, Will Luther, and Chuck Moulton.

For historical information, references, and written comments on various chapters I am indebted to many people in many places, including Neera Badhwar, John Blundell, Bruce Caldwell, Balakrishnan Chandrasekaran, Richard W. Fulmer, Steve Horwitz, Jeff Hummel, Doug Irwin, Ekkehard Köhler, Meir Kohn, Shruti Rajagopalan, Mario Rizzo, George Selgin, Gurbachan Singh, T. N. Srinivasan, and John Wood. An anonymous reviewer for Cambridge University Press was especially helpful in suggest- ing final revisions.

Joey Bahun and Alex Salter provided able research assistance. Kyle O’Donnell prepared the index.

Just before I began this project I received a kidney from my heroic cousin, Roger Hitchner. Thanks, Roger. It would have been much more difficult to write anything, not to mention to enjoy a normal life in other respects, had I continued to be on hemodialysis.

My greatest debt is to my wife, Neera Badhwar, for love and encouragement.

1

The last hundred years have seen dramatic experiments in economic pol- icy: the adoption of central banking in the United States and elsewhere;

command economies during the First World War; communist central plan- ning in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China; fascism in Mussolini’s Italy; National Socialism in Hitler’s Germany; the New Deal in Roosevelt’s United States; the Bretton Woods international monetary system and the adoption of Keynesian macroeconomic policies after the Second World War; major nationalizations in postwar Great Britain; the reemergence of free-market principles in postwar Germany; Soviet-style Five-Year Plans in India; the final abandonment of gold in favor of a system of fluctuating exchange rates among unanchored government fiat monies; regulation and deregulation and reregulation around the globe; the collapse and repudia- tion of communism in Russia and Eastern Europe; market-led growth pol- icies in the East Asian “tigers” and then in China and India; “neoliberal”

policies promoting the globalization of economic activities. In recent years an unhappy sequence – a worldwide housing credit bubble, followed by the collapse of mammoth financial institutions, followed by expensive govern- ment bailouts and takeovers, followed by record-breaking budget deficits and fiscal crises – has returned the issues of monetary policy, regulation, nationalization, and fiscal policy to the front of the economic policy stage across the developed world.

Behind these movements and countermovements in economic policy lies an ongoing and often dramatic clash of economic ideas. The chapters that follow trace the connections running from historical events to debates among economists, and from economic ideas to major economic policy experiments. They will dig selectively into the history of economic doc- trines – back to Adam Smith when necessary – to understand how the ideas originated and developed over time to take the forms that they did.

Economists are notorious for the frequency of their policy disagree- ments. “If all the economists were laid end to end, they still would not reach a conclusion,” goes one version of a witticism sometimes attributed (without evidence) to George Bernard Shaw. Because this book focuses on disagreements, a disclaimer is in order. The immediately policy- relevant parts of economic thought are not the whole of economic thought, and the other parts involve somewhat less disputation and more collabora- tion. Because the noneconomist hears much less about economists’ policy- detached work, which focuses mainly on technical issues in dissecting and understanding observed economic phenomena, it is easy to form the false impression that disagreements over policy occupy more of the typical pro- fessional economist’s efforts than they do. The economist George Stigler once rightly noted:

The proposition that the economist is not addicted to taking frequent and disputatious policy positions will appear incredible to most noneconomists, and implausible to many economists. The reason, I believe, for this opinion is that in talking to a noneconomist, there is hardly anything in economics except policy for the economist to talk about. The layman would find [the economist’s technical work] . . . quite incomprehensible. The typical article in a professional journal is unrelated to public policy – and often apparently unrelated to this world.1

In this book the focus is on economic theory and empirical work that are related to public policy, though much of the literature was written for other economists rather than for the layman. The chapters look into the substance and impact of the disputed positions. How have economists thought – and argued – about the great economic policy issues? How have they sometimes influenced policy and institutional design?

Given the book’s focus on the policy-relevant parts of economics, it is natural to proceed policy issue by policy issue, framing each issue with an important historical debate or policy experiment. This approach contrasts with encyclopedic histories of economic thought that proceed thinker by thinker in chronological order, beginning with the ancients or the Scholastics or the mercantilists. Within each chapter, when necessary to explain how economists came to think as they did about the issue at hand, there will be flashbacks to the theoretical developments and debates of previous centu- ries. If a defense of this nonlinear approach is needed, one has been offered by the filmmaker Quentin Tarantino, who told a British interviewer: “When

1 George Stigler, “The Economist as Preacher,” in Kurt R. Leube and Thomas Gale Moore, eds., The Essence of Stigler (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986), p. 305.

I made Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction nonlinear, I was not just doing it to show what a clever boy I was. Those stories were better served dramatically to be done the way I did them.”2 Sometimes the most vivid way to tell the story of an intellectual debate similarly involves flashbacks. Thus the reader should not think of the chapters that follow as chronologically scrambled or filled with detours. Think of them as Tarantinoesque – only with more polite language and slightly less bloodshed.

AN ovERvIEW oF THE CoMING CHAPTERS

The episodes and debates examined here were chosen for their histori- cal importance and for the light they shed on how the rival positions have evolved that are held in today’s major disagreements over economic pol- icy. Policy-relevant theorizing rarely arises in a self-contained ivory tower, or purely in response to other theories. Economists read the newspapers.

Theory develops to grapple with the issues and events of the day. This is why the chapters use the history of the last one hundred years to frame the economic policy debates.

Chapter 1 sets the stage, describing economic thought on the verge of the First World War. It introduces two figures who will reappear throughout the book, the English economist John Maynard Keynes and the Austrian economist Friedrich A. Hayek. Each subsequent chapter begins with a major economic problem that triggered or revived debate among econo- mists, or a policy experiment to which economists contributed. Chapter 2 examines the issue of central economic planning versus the market price system, starkly posed by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and developed in the crucial “socialist calculation debate.” Chapter 3 examines pre-Keynes- ian business cycle theory, in particular the theory developed by Hayek and other Austrian economists, in light of the boom of the Roaring Twenties that ended in the crash of 1929. The New Deal policy experiment of the early 1930s followed in the United States, and Chapter 4 traces its origins to the institutionalist school of economics, especially as represented by the economist Rexford G. Tugwell. The Great Depression dragged on. Chapter 5 relates how Keynes’s 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money fomented a revolution in economic thinking about the causes of ups and downs in the economy as a whole.

2 Quentin Tarantino, “Interview with Quentin Tarantino,” Guardian, 5 January 1998,http://

film.guardian.co.uk/Guardian_NFT/interview/0,,78433,00.html.

Chapter 6 focuses on a very different book, Hayek’s Road to Serfdom of 1944, which grew out of his concern about the dangers of continuing the central planning policies pursued during the Second World War. In the immediate postwar period, very different economic policy paths were taken by different nations. Chapter 7 chronicles the nationalizations undertaken by the Labour Party in Great Britain and traces those policies to the socialist ideas that the Fabian Society had tirelessly developed and advocated in the previous six decades. Chapter 8 tells the story of a society with a strongly contrasting policy outlook, the Mont Pelerin Society, which Hayek founded after the war to rally the intellectual opponents of socialism. Chapters 9 and 10 offer case studies of two countries that headed in very different direc- tions and had very different results over the next thirty years. With impor- tant input from some Mont Pelerin Society economists, Germany moved in a market-friendly direction and prospered. With important input from Fabian thinkers, India adopted nationalization and quasi-Soviet Five-Year Plans and did not prosper.

The next two chapters examine postwar developments in monetary regimes and policies. Chapter 11 tells the story of the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, how and why Keynes and other economists there hashed out an international monetary system that reduced the role of gold and allowed greater scope for discretionary national monetary policies. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, for reasons that economists have debated. Its collapse coincided with the onset of a period of high infla- tion that, Chapter 12 recounts, served as the seedbed for the revival and development of “monetarist” ideas by Milton Friedman and others, who challenged the dominance of Keynesian thinking. Chapter 13 notes the growth of government in the postwar era and contrasts two leading eco- nomic theories that see the growth of government through very different lenses: the optimistic-about-government theory of public goods and the cynical-about-government theory of public choice. The growth of inter- national trade in the postwar era frames Chapter 14’s discussion of the long-running debate between free traders and protectionists. Chapter 15 examines the clash between Keynesian and “new classical” economists over the benefits and costs of government budget deficits and debt. The debate over deficits and debt has naturally reemerged with the sovereign debt crises of Greece and Ireland in 2010, followed by Portugal in 2011 with Italy and Spain in the wings, and the growing indebtedness of other national governments including those of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Do ECoNoMIC IDEAS HAvE CoNSEQUENCES?

Does the clash of ideas among economists really matter for practi- cal policy making? Do economic ideas have consequences? Economists have clashed over that issue, too. Both Keynes and Hayek thought that the impact of economic ideas on public policy was profound. In his essay “The Intellectuals and Socialism” Hayek wrote:

[T]he views of the intellectuals influence the politics of tomorrow. . . . What to the contemporary observer appears as the battle of conflicting interests has indeed often been decided long before in a clash of ideas confined to narrow circles.3

Keynes declared, in a passage from his 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money that academic economists love to quote (for obvious reasons):

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood.

Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.4 other economists have disputed the hypothesis advanced by Hayek and Keynes. The great Italian economist vilfredo Pareto offered a diametrically opposed view in his book The Mind and Society (1935). In Pareto’s view, the politically dominant interests in a society, calculating what best serves their well-being given the sociopolitical environment, determine both the eco- nomic policies that its government chooses and the economic theories that its mainstream academicians adopt. Academic theories are mere window dressing with no impact on the policies chosen.

Pareto summarized his view using the example of international trade policy. When the state of elite opinion, “a psychic state that is in great part the product of individual interests, economic, political, and social, and of the circumstances under which people live,” turns toward protection- ism, Pareto argued, a country’s trade policy will eventually change toward protectionism. At the same time, “modifications in [trade theory] will be

3 F. A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” in Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969), p. 179. Hence this book’s title.

4 John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London:

Macmillan, 1936), p. 383.

observable and new theories favorable to protection will come into vogue.”

Thus a “superficial observer may think that [trade policy] has changed because [trade theory] has changed,” when actually both have changed with interests and circumstances. That theorists influence policy makers is an illusion: “Theoretical discussions . . . are not, therefore, very serviceable directly for modifying” policy.5

The University of Chicago economist George Stigler took a similarly cyn- ical view. In his well-known essay “The Economist as Preacher” he urged his fellow economists to give up the fond hope that by preaching the mer- its of economic efficiency to policy makers they could convince them to mend their inefficient ways. In Stigler’s view “the assumption that public policy has often been inefficient because it was based on mistaken views has little to commend it,” because it cannot explain why policies like tariffs persist for decades despite knowledge of their effects. Instead the econo- mist should assume that politicians are pursuing their own goals, distinct from overall prosperity, and that tariffs represent “purposeful action” that achieves the politician’s goals with “tolerable efficiency.” Namely, “Tariffs were redistributing income to groups with substantial political power, not simply expressing the deficient public understanding” of the argument that free trade promotes overall prosperity.6 That Stigler bothered to preach this message to his fellow economists, who by the same logic must be consid- ered self-interested pursuers of their own goals when they persist in their preaching ways, is something of a paradox.

In response to Keynes’s previously quoted statement about the influence of the “academic scribbler,” a follower of Pareto commented:

[T]he politician has a vast choice as to the scribbling, since there is almost no hypothesis that has not been expounded at some time by a so-called econ- omist. Hence, it remains true that the politician, not the writer, is the active factor which determines the trend.7

Some cases discussed in the chapters that follow seem to fit Pareto’s view, especially cases in which the theoretical rationale for a policy was provided after the fact. Politicians embraced “Keynesian” deficit spending to combat the Great Depression well before interpretations of Keynes’s General Theory became available to motivate such policies. (Similar ideas had long been

5 vilfredo Pareto, The Mind and Society, vol. 1, ed. Arthur Livingston, trans. Andrew Bongiorno and Arthur Livingston (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1935), p. 168.

6 George Stigler, Essence of Stigler, pp. 308–9.

7 otto von Mering, “Some Problems of Methodology in Economic Thought,” American Economic Review 34 (March 1944, Part I), p. 97.

available, but few respected economists had endorsed them.) other impor- tant cases fit better the view of Keynes and Hayek that academic ideas have had important policy consequences, such as the repeal of the British Corn Law tariff in 1846 (discussed in Chapter 14) and the formulation of the first New Deal programs of 1933 (Chapter 4).8

THE STRUCTURE oF INTELLECTUAL PRoDUCTIoN

Commercial forests produce trees, which go to sawmills to be turned into lumber, which factories then embody in furniture for ultimate consum- ers. Hayek’s and Keynes’s remarks suggest a similar structure to intellec- tual production. High-level economic researchers produce abstract ideas, which applied economic researchers turn into less abstract policy ideas, which journalists and intellectuals then embody in mass-market books, op-ed pieces, and radio and television commentary for the consumption of policy makers and the public. James M. Buchanan and Richard E. Wagner have described the spread of Keynesian economics in just this way: “The American acceptance of Keynesian ideas proceeded step by step from the Harvard economists, to economists in general, to the journalists, and, finally, to the politicians in power.”9

At the earliest stage of intellectual production, academic economists seeking to advance their understanding of the world develop ideas that (they hope) will be found useful and novel by other researchers. They distribute their findings through articles in scholarly journals and mono- graphs from university presses. Examples of such economics-for-other- economists discussed in later chapters include Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Hayek’s The Pure Theory of Capital, and Milton Friedman’s A Theory of the Consumption Function. At the next stage, in applied research, academic and think-tank economists seek to develop the ideas further, particularly by confronting them with historical and sta- tistical evidence, in ways that (they hope) will be useful and interesting to journalists and economics instructors. They publish books for intelli- gent laymen, textbooks, and reports. Examples include Keynes’s Essays in Persuasion, Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, and Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom.

8 For a critical take on intellectuals and the impact of their ideas see Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Society (New York: Basic Books, 2010).

9 James M. Buchanan and Richard E. Wagner, Democracy in Deficit (San Diego: Academic Press, 1977), p. 6. The most important economist to apply and popularize Keynesian ideas at Harvard during the postwar period was Alvin Hansen, as discussed in Chapter 15.

At the third stage (the divisions here are of course somewhat arbitrary), journalists and sometimes economists themselves sort through and repack- age applied research to provide ideas to policy makers and the general public. They lecture to college students, publish newspaper and magazine columns, write blogs, and appear on Tv and radio talk shows. The Nobel laureate economists Friedman and Paul Samuelson wrote regular columns for Newsweek magazine. Thomas Sowell, a former student of Friedman, writes a widely syndicated column. Paul Krugman, a former student of Samuelson, writes a column and a blog for the New York Times. (of course, neither Sowell nor Krugman confines the topics of his columns to econom- ics.) The economist John Kenneth Galbraith wrote best-selling books and hosted a PBS series, The Age of Uncertainty. Friedman responded with his own PBS series, Free to Choose.

At the end-user stage of the production and distribution of economic policy ideas comes real-world political application. If we arrange the stages from top to bottom, with ideas moving downward from the theoretical heights (think “ivory tower”), politics becomes the lowest stage, which some may think appropriate. The real point of picturing intellectual activity this way, though, is to give greater concreteness to the view that to understand economic policy change one needs to understand the preceding develop- ments in economic ideas from pure theory on down.

GovERNMENTS vERSUS MARKETS

Economic policy ideas clash when their advocates have different views about the role government should play in the economy. As the narrator of the 2002 PBS documentary series The Commanding Heights intoned (in his authoritative narrator’s voice), the twentieth century witnessed

a century-long battle as to which would control the commanding heights of the world’s economies – governments or markets; the story of intellectual combat over which economic system would truly benefit mankind. . . . 10 Here the “commanding heights” of an economy – a phrase due to the Russian revolutionary vladimir Lenin – basically means the institutions that steer the economy by deciding where investment funds go. Government control over the commanding heights is seen in state direction of the major banks and industries (formal state ownership is not necessary if state

10 The Commanding Heights Episode One: The Battle of Ideas, video transcript, http://www.

pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/tr_show01.html.

regulation is pervasive enough), dominance of the bond market by govern- ment issues, a limited or nonexistent stock exchange for shares in privately owned firms, and possibly a central economic planning board.

Are competitive markets, guided by impersonal forces of profit and loss, better than government command-and-control for directing investment toward the greatest prosperity? The key insight of economics as a disci- pline – its greatest contribution to understanding the social world and to avoiding harmful policies – is that, under the right conditions, an economic order arises without central design that effectively serves the ends of its par- ticipants. In Adam Smith’s analysis and famous phrase, investors are “led by an invisible hand” that aligns their private pursuit of profits with (what is no part of their intention) the greatest contribution to the economy’s overall prosperity. Chapter 8 directly examines this Smithian idea in detail, while Chapter 13 considers modern challenges to it. But debates over the relative reliability of markets and governments for steering the economy recur in every chapter of the book.

It should be noted that when economists speak of “which economic sys- tem would truly benefit mankind,” their emphasis is normally on satisfy- ing human preferences as they currently exist, not on morally reforming mankind. In this way they can focus on the cause-and-effect or if-then questions that their economic training equips them to address, and finesse questions of moral philosophy. An economist who says, “If the govern- ment imposes and enforces an excise tax on whiskey, then it will reduce the volume of whiskey sold,” is advancing a value-neutral or positive prop- osition. It is as true for the listener who favors allowing whiskey buyers and sellers to satisfy their preferences as it is for the listener who wants to reduce whiskey sales through tax policy when moral reformation proves ineffective.

The ideal of value-freedom (sometimes known by the German term wertfreiheit) has a great deal to recommend it in pure economic research.

Policy advice, by contrast, can hardly avoid embodying value-laden or normative propositions. A policy commentator whose advice rests on the proposition that “the government should not interfere with the satisfaction of consumer preferences as they currently exist” or “a higher average real income in society is better than a lower one” is mixing in a normative prop- osition – whether controversial or not – that lies outside positive econom- ics. Economists have often left the normative propositions underlying their policy advice implicit. The critic of a policy prescription may reject either the normative presuppositions or the positive analysis that goes into it (or both). For the sake of clarity it is helpful to identify which it is.

Greater preference-satisfaction is reflected in the aspects of life that peo- ple care about. For most people these aspects can be judged by measurable indicators like better nutrition, longer life expectancy, more leisure, greater material comfort, a wider variety of enjoyments, and cultural and environ- mental amenities. Taking prosperity as a blanket term for the abundance of means by which individuals can satisfy their preferences, and assuming that most people are concerned to have greater prosperity rather than less, the key question for an economic analysis that speaks to the concerns of most people is, Which economic system – government or market control of the commanding heights – delivers more prosperity? The answer to this ques- tion depends on the underlying analytical questions: How and why does each system perform the way it does? Economists who favor free markets with minimal government interference tend to frame the choice as an up- or-down vote on government control. Economists who favor a larger role for government tend to frame the question as one of finding the best mix (or balance) of market and government control.

SoCIALISM vERSUS CAPITALISM

A system of government control over the commanding heights of the economy, over the financial system and major industries, is more simply called socialism. There are at least as many different types of socialism, however, as there are different techniques of government control over the commanding heights. The alternative of leaving finance and production in private hands subject to the guidance of free market forces – competition, profit and loss, supply and demand, the price system – is more simply called capitalism. This term is equally fraught with complications. “Free-market capitalism” or simply “a free economy” is a clearer way to designate the antithesis of socialism, because phrases like “crony capitalism” and “state capitalism” are often used to refer to an industrial economy molded by gov- ernment direction rather than guided by free market forces.

Jeffrey Sachs, a Columbia University economist well known for his efforts to persuade the governments of rich nations to give more aid to the gov- ernments of poor nations, has summarized the outcome of the twentieth- century battles over economic policy as follows:

Part of what happened is a capitalist revolution at the end of the 20th century.

The market economy, the capitalist system, became the only model for the vast majority of the world.11

11 Ibid.

Sachs here used “capitalist system” as a fairly value-neutral synonym for

“a market-directed economy.” others have of course used it less neutrally.

Karl Marx in the nineteenth century famously gave the term “capitalist system” (or simply “capitalism”) strongly negative connotations. Just as monarchism is a regime favoring privileged monarchs, and mercantilism is a regime favoring privileged merchants, “capitalism” in the Marxian usage is a regime favoring privileged capitalists, the profit-seeking owners of finan- cial wealth. David N. Balaam and Michael veseth note that Lenin’s analy- sis, like Marx’s, “is based on the assumption that it is in capitalism’s nature for the finance and production structures among nations to be biased in favor of the owners of capital.”12 We will examine Marx’s views in Chapter 2.

Capitalism in Marx’s sense implies the exploitation of workers by capitalists.

Marx prophesied that modern capitalism, though it had displaced medie- val feudalism with a vastly more productive system, would inevitably give way to socialism and finally to communism, a system of rule by labor com- munes with resources under collective ownership.

The Marxian overtones to the term “capitalism” led Hayek to comment that he himself used the term “only with great reluctance, since with its modern connotations it is itself largely a creation of that socialist interpre- tation of economic history.” He later explained that the term is “misleading because it suggests a system which mainly benefits the capitalists, while it is in fact a system which imposes upon enterprise a discipline under which the managers chafe and which each endeavours to escape.”13 For Hayek as for Adam Smith, the aim of promoting a competitive market economy with decentralized and private property ownership was to further the interests of ordinary workers and consumers, not of businessmen as a class. The clash of economic ideas is distinct from the clash of political interest groups. The central theme of the chapters to come is not a clash over whose interests the economy should serve, but over how best to foster the prosperity of the economy’s average participant.

12 David N. Balaam and Michael veseth, Introduction to International Political Economy, 2nd ed. (New York: Prentice-Hall, 2001), p. 69.

13 F. A. Hayek, “Introduction,” in Hayek, ed., Capitalism and the Historians (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1954); Hayek, Law, Legislation, and Liberty, vol. 1 (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1973), p. 62.

12

The Turn Away from Laissez-Faire

At England’s stately University of Cambridge in fall 1905, a clever post- graduate mathematics student named John Maynard Keynes began his first and only course in economics. He would spend eight weeks studying under the renowned Professor Alfred Marshall. During the summer Keynes had read the then-current (third) edition of Marshall’s Principles of Economics, a synthesis of classical and new doctrines that was the leading economics textbook in the English-speaking world. Marshall was soon impressed with Keynes’s talent in economics. So was Keynes himself. “I think I am rather good at it,” he confided to an intimate friend, adding, “It is so easy and fascinating to master the principle of these things.” A week later he wrote:

“Marshall is continually pestering me to turn professional Economist.”1 At an Austrian army encampment on the bank of the Piave River in northern Italy during the last months of the First World War, a lull in combat gave a young lieutenant named Friedrich August von Hayek the chance to open his first economics texts (not counting the socialist pam- phlets he had read during college), two books lent to him by a fellow officer.

He later wondered why the books had not given him “a permanent dis- taste for the subject” because they were “as poor specimens of economics as can be imagined.” Returning to the University of Vienna after the war, the young veteran “really got hooked” on economics when he discovered a book by the retired professor Carl Menger. Menger’s Principles of Economics (Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre) of 1871 had colaunched a marginal- ist-subjectivist revolution in economic theory, a revolution that provided the new ideas in Marshall’s synthesis. Hayek found it “such a fascinating book, so satisfying.”2

1 Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes, vol. 1 (London: Macmillan, 1983), pp. 165–6.

2 F. A. Hayek, Hayek on Hayek: An Autobiographical Dialogue, ed. Stephen Kresge and Leif Wenar (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), pp. 47–8. Hayek identified the

Keynes and Hayek would come to play leading roles in the clash of eco- nomic ideas during the Great Depression. Their ideas have informed the fundamental debates in economic policy ever since. In 2010 and 2011 their intellectual rivalry even became the subject of two viral rap videos.3

JoHn MAynARD KEynES

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) was the son of the English economist John neville Keynes. At the University of Cambridge, where his father lec- tured, he studied mathematics but also pursued interests in philosophy and, as noted, took one economics course from Marshall. After a brief stint in the civil service Keynes began lecturing in the Cambridge economics depart- ment in 1909, sponsored by Marshall, and became editor of the Economic Journal two years later. In 1915 he became an adviser to, and then an official within, the UK Treasury. Four years later, at age thirty-six, Keynes was a British delegate to the Versailles Peace Conference following the First World War. His best-selling insider’s account and critique of the peace treaty, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), brought him widespread fame.

In the next three decades Keynes kept busy writing books and articles, lecturing at Cambridge, editing The Economic Journal, speculating in the London financial markets, and advising the British government.4 In all this activity, Keynes displayed what Daniel yergin and Joseph Stanislaw have described as a “dazzling, wide-ranging intellect . . . combined with chronic social and intellectual rebellion, orneriness, and the lifestyle of a Bloomsbury bohemian and aesthete.”5 Although his sexual relationships as a young adult had almost entirely been with men,6 Keynes around 1922

authors of the two awful books only as “Gruntzl and Jentsch.” He may have meant Josef Grunzel, Grundrisse der Wirtschaftpolitik (Vienna: Hölder, 1909–10), and Carl Jentsch, Grundbegriffe und Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaft (Leipzig: Grunow, 1895).

3 “Fear the Boom and Bust” and “Fight of the Century,” written by John Papola and Russ Roberts, available online at econstories.tv. Within a month of its January 2010 release on youTube the first video had registered more than 800,000 views. In July 2011 its count reached 2.5 million, while the sequel (released April 2011) surpassed 1 million views.

4 For a detailed chronology of Keynes’s career, see http://www.maynardkeynes.org/keynes- career-timeline.html. The authoritative biography is Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes, 3 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1983, 1992, 2000), also available in an abridged sin- gle volume (new york: Penguin, 2005).

5 Daniel yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy (new york: Simon & Schuster, 2002), p. 40. Bloomsbury was a fashionable neighborhood in London.

6 Keynes recorded his sexual affairs in secret diaries. For some details see the appendix, “A Key for the Prurient: Keynes’s Loves, 1901–15,” in D. E. Moggridge, Maynard Keynes: An Economist’s Biography (London: Routledge, 1992).

surprised his Bloomsbury friends by taking up with Lydia Lopokova, a Russian ballerina. They married in 1925 and remained happily married for the rest of his life.

In A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), Keynes argued against a post- war return to the gold standard at the traditional parity, on the sensible grounds that it would require a painful deflation of prices and wages. The central bank should instead let the exchange rate float and target the price level. In A Treatise on Money (1930, 2 vols.), published early in the Great Depression, Keynes offered a theory of the business cycle that drew on the work of his teacher Alfred Marshall and on the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell. Hayek severely criticized the work in a lengthy two-part review. Keynes went back to the drawing board and authored the book for which he is best known, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936). There he argued that the economy’s current aggregate out- put is governed by its current aggregate demand, and that the most volatile component of aggregate demand is current investment spending. Keynes’s diagnosis of the Great Depression boiled down to: investors had lost their nerve. His remedy: government must expand its spending to boost aggre- gate demand and particularly investment. We will consider this theory and its predecessors in more detail in Chapter 5.

FRIEDRICH A. HAyEK

Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992) was likewise born into an intellectual family, his father a professor of botany at the University of Vienna. After serving the last year of the First World War as a draftee on the Italian front, Hayek returned home to study economics and psychology at the University of Vienna, finally choosing economics in part because the job prospects were better. He studied with Friedrich von Wieser, a fol- lower of the pioneering neoclassical economist Carl Menger (whose ideas are discussed in Chapter 8). After graduation he secured a job working under Vienna’s leading economist, Ludwig von Mises. From March 1923 to May 1924 Hayek took a leave of absence to visit the United States, where he met many of the leading American economists of the day. After his return to Vienna he headed a business cycle research institute that Mises had founded.

Initially socialist in his sympathies as a student, Hayek was deeply influ- enced by Mises’s critical book on Socialism (1922), and later reinforced Mises’s arguments with his own critique of contemporary “market socialist”

ideas (see Chapter 2). A collection of Hayek’s articles, Individualism and

Economic Order (1948), included his critiques of market socialism and also important essays on crucial role of market prices as signals that enable soci- ety to coordinate the efforts of millions of decentralized decision-makers.

Hayek emphasized the “marvel” that the price system achieves an intricate economic order coordinating millions of plans and bits of dispersed knowl- edge – thereby allowing the efficient use of resources – without central design.7

Hayek’s early works were mostly devoted to the problem of business cycles. He wrote Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle (German edition 1929) and Prices and Production (1931), the latter in English based on guest lectures Hayek had given at the London School of Economics. The LSE eco- nomics department headed by Lionel Robbins hired Hayek in the wake of the lectures, and he taught there until 1950. In Hayek’s business-cycle the- ory, based primarily on earlier work by Mises and Wicksell, the economic boom period is fueled by artificially cheap credit. (Both Keynes and Hayek drew from Wicksell’s work, but they drew from different parts.) The credit- fueled boom inevitably ends in bust because the unsustainably low interest rate has lured investment into forms that turn unprofitable when, as it must, the interest rate rises toward equilibrium. We will consider this theory and its predecessors in detail in Chapter 3. Prices and Production was severely criticized by Keynes and others. Returning to the drawing board, Hayek published Profits, Interest, and Investment (1939) and The Pure Theory of Capital (1941).

During the Second World War, Hayek published the popular book for which he is best known, The Road to Serfdom (1944). In it he warned of the dangers of central planning for personal and social freedom (see Chapter 6). Hayek founded the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947 as an organization to rally the few remaining classical liberal intellectuals who shared his oppo- sition to the trend toward a larger government role in the economy and society (see Chapter 8).

With his research migrating from pure economics into social philoso- phy, and with his decision to leave his first wife to marry another woman (which estranged him from Robbins), Hayek moved to a position in the

7 For an intellectual biography of Hayek see Bruce Caldwell, Hayek’s Challenge (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2004). See also Gerald P. o’Driscoll, Jr., Economics as a Coordination Problem: The Contributions of Friedrich A. Hayek (Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977); and G. R. Steele, The Economics of Friedrich Hayek (new york:

St. Martin’s Press, 1993). For Hayek’s own reminiscences see F. A. Hayek, Hayek on Hayek:

An Autobiographical Dialogue, ed. Stephen Kresge and Leif Wenar (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago in 1950.8 There he wrote The Constitution of Liberty (1960), an exposition of his classical liberal political philosophy. He returned to Europe in 1962 to take a chair at the University of Freiburg in Germany. In 1974 he was corecipient of the Bank of Sweden Memorial Prize in Economic Science in Honor of Alfred nobel (hereafter we will abbreviate the prize’s name). Two years later, at the age of 77, he published a remarkably radical monograph calling for the Denationalisation of Money. He returned to the topic of socialism in his final work, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (1989).9

KEynES on THE EnD oF LAISSEz-FAIRE

Keynes flatly rejected Adam Smith’s doctrine of the invisible hand. In the opening paragraph of a 1924 lecture published in 1926 as an essay entitled

“The End of Laissez-Faire” he declared:

The world is not so governed from above that private and social interest always coincide. It is not so managed here below that in practice they coincide. It is not a correct deduction from the principles of economics that enlightened self-interest always operates in the public interest. nor is it true that self- interest generally is enlightened; more often individuals acting separately to promote their own ends are too ignorant or too weak to attain even these.10 Specifically, Keynes denied that decentralized market forces were adequate for determining the volumes and allocations of saving and investment:

I believe that some coordinated act of intelligent judgement is required as to the scale on which it is desirable that the community as a whole should save, the scale on which these savings should go abroad in the form of foreign investments, and whether the present organisation of the investment mar- ket distributes savings along the most nationally productive channels. I do not think that these matters should be left entirely to the chances of private judgement and private profits, as they are at present.11

8 The other woman was his first cousin Helene, who had been his childhood sweetheart.

They had corresponded for years and reconnected in Vienna in 1946. Hayek spent the 1951 spring semester at the University of Arkansas to take advantage of the state’s liberal divorce laws. For more details on Hayek’s divorce see Alan Ebenstein, Hayek’s Journey: The Mind of Friedrich Hayek (new york: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 123.

9 F. A. Hayek, The Denationalisation of Money, 2nd ed. (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1978); Hayek, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism, ed. W. W. Bartley III (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

10 John Maynard Keynes, “The End of Laissez-Faire” [1926], in Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (new york: W. W. norton, 1963), p. 312.

11 Ibid, pp. 318–19.

In The General Theory Keynes would emphasize his view that market forces could not be counted on to deliver a great enough volume of invest- ment in the aggregate. An enlightened government should take control.

KEynES VERSUS HAyEK on THE RoLE oF GoVERnMEnT Keynes was a leading advocate of the view that government should take greater control over the economy. Hayek was a leading advocate of the view that government should interfere less with market forces. They serve as rep- resentatives of the opposing sides here because of their wide influence, not because either took the most polar position available. Keynes did not want to abolish markets the way communist thinkers would. Keynes explicitly rejected Russian communism for three reasons: (1) It “destroys the liberty and security of daily life”; (2) its Marxian economic theory is “not only sci- entifically erroneous but without interest or application for the modern world” and its Marxist literature more generally is “turgid rubbish”; and (3) it “exalts the boorish proletariat above the bourgeois and the intelligent- sia” – in other words, sneers at people like Keynes and his circle.12 Hayek did not want to abolish government the way anarcho-capitalist thinkers would.

(yes, there really are serious proponents of a stateless market economy.)13 For most of the twentieth century, Keynes’s view that government should take on a greater role in the economy prevailed among opinion-makers.

And the role of government grew. While Keynes was not an advocate of complete state planning, he did endorse greater planning. In a letter to Hayek, responding to Hayek’s critique of state planning in The Road to Serfdom, Keynes wrote:

I should say that what we want is not no planning, or even less planning, indeed I should say that what we almost certainly want is more.14

In The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) Keynes called for “a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment” which

12 John Maynard Keynes, “A Short View of Russia” in Keynes, Essays in Persuasion, pp. 299–300.

13 Two important contributors are Murray n. Rothbard, For a New Liberty, rev. ed. (new york: Collier, 1978), and David D. Friedman, The Machinery of Freedom (Chicago: open Court, 1989). A well-known work in political philosophy, Robert nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia (new york: Basic Books, 1974), devotes its first third to wrestling with anar- chocapitalism. Proponents and critics are both represented in Edward P. Stringham, ed., Anarchy and the Law (oakland, CA: Independent Institute, 2007).

14 Donald Moggridge, ed., John Maynard Keynes, The Collected Writings, vol. 27: Activities, 1940–1946 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), p. 387.

he believed would provide “the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.” His focus there was on economy-wide aggregates rather than on details of resource allocation. He emphasized that his proposal for

“socialization of investment” did not imply full State Socialism in the sense of outright government ownership of factories:

It is not the ownership of the instruments of production which it is impor- tant for the State to assume. If the State is able to determine the aggregate amount of resources devoted to augmenting the instruments and the basic rate of reward to those who own them, it will have accomplished all that is necessary.15

The government need not own the factories if it can otherwise bring about the proper volume of total investment spending. Keynes prescribed a greater volume of investment than he thought the market would deliver.

A greater volume of investment would reduce the rate of return on invest- ment. He envisioned the “euthanasia of the rentier” (the person who lives on interest income) and “the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist,” meaning a policy that would drive the rate of return so low – perhaps even to zero – that no wealth-owner could live solely on the returns from his investments.16

Keynes also suggested a greater role for government in labor mar- kets, questioning in a 1925 essay “whether wages should be fixed by the forces of supply and demand in accordance with the orthodox theories of laissez-faire, or whether we should begin to limit the freedom of those forces by reference to what is ‘fair’ and ‘reasonable’ having regard to all the circumstances.”17

PoLITICAL EConoMy In AMERICA’S PRoGRESSIVE ERA Economic ideas supporting the expansion of government’s role in the economy certainly did not begin with Keynes. Indeed they did not even begin in the twentieth century. In the late nineteenth century the United States, for example, entered a period of ideological change toward more active government, a period now called the Progressive Era. numerous

15 John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London:

Macmillan, 1936), pp. 377–8.

16 Allan H. Meltzer, Keynes’s Monetary Theory: A Different Interpretation (new york:

Cambridge University Press, 1988), emphasizes that “Keynes favored state direction of investment from the mid-1920s” (p. 5) and views The General Theory as Keynes’s attempt to provide a theoretical underpinning for that long-held belief.

17 John Maynard Keynes, “Am I a Liberal?” [1925], in Keynes, Essays in Persuasion, p. 333.

economists played important roles in the ideological and political move- ment, developing arguments and promoting legislation to increase the role of the federal government in the economy, from the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) to the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1906) to the Federal Reserve Act (1913). As Thomas C. Leonard has put it, “In the three to four decades after 1890, American economics became an expert policy science and academic economists played a leading role in bringing about a vastly more expansive state role in the American economy.”18

In the late 1870s and 1880s young American economists were returning from graduate training in Germany with ideas and approaches that they developed into a school of thought that came to be known as institutionalist economics. In 1885 the thirty-one-year-old Richard T. Ely of Johns Hopkins University led a group of these economists in founding the American Economic Association (AEA). The AEA quickly became (and remains) the leading professional organization of economists, but among its original mis- sions was to organize economists opposed to laissez-faire ideas. The AEA’s initial Statement of Principles affirmed “the state as an agency whose posi- tive assistance is one of the indispensable conditions of human progress.”19 Ely and economist John R. Commons went on to influence labor policy reforms during the Progressive Era as leaders of the American Association for Labor Legislation (AALL). The AALL was founded in 1906 with Ely as its first president and Commons soon becoming its secretary.20

Ely and his compatriots saw themselves as a “new school” of dissenters from classical or neoclassical economics and from the doctrine of laissez- faire. Ely wrote in 1886 of “the controversy between the economists of the old school,” meaning the classical and neoclassical economists and defenders of laissez-faire, and the economists of “the new school in America,” meaning the institutionalists and Progressives like himself. He described the “new school” thinkers as scientific truth-seekers whose historical investigations

18 Thomas C. Leonard, “Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19 (Autumn 2005), p. 207.

19 on Ely’s life and influence see Benjamin G. Rader, The Academic Mind and Reform: The Influence of Richard T. Ely in American Life (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1966). The AEA Statement of Principles is quoted by Bradley W. Bateman and Ethan B.

Kapstein, “Between God and the Market: The Religious Roots of the American Economic Association,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 13 (Fall 1999), p. 253. Institutionalism and its German roots will be discussed in Chapter 4.

20 David A. Moss, Socializing Security: Progressive Era Economists and the Origins of American Social Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996); John Dennis Chasse,

“The American Association for Labor Legislation: An Episode in Institutionalist Policy Analysis,” Journal of Economic Issues 25 (September 1991), pp. 799–828.

had uncovered the benefits of labor unionization and strikes, had found in socialism “important and fruitful truths which have been unfortunately overlooked,” and had “overthrow[n] many cherished dogmas” of orthodox finance. As a result there were now “political economists teaching differ- ent doctrines from the theories previously received by the more influential elements in society.” Ely elaborated the same theme at greater length in an 1884 monograph, where he explicitly tied the new school in America to the teachings of German historical economists.21

In Great Britain of the same decade, the up-to-date economist’s case against laissez-faire was mostly based on finding theoretical exceptions to the rule rather than on historical investigation. Henry Sidgwick observed in his Principles of Political Economy (2nd ed., 1887) that although most eco- nomic commentators of his day still considered the case for laissez-faire in the area of international trade, that is, the case for unilateral free trade, “to be as evident and cogent as a mathematical demonstration,” that area was an exception, and “only a few fanatics would now use similar language in discussing any other particular application of the general doctrine of lais- ser faire.” The old view “that the self-interest of individuals would always direct them to the industrial activities most conducive to the wealth and well-being of the community of which they are members,” together with the kindred belief in “the harmony of the interest of each industrial class with the interest of the whole community,” Sidgwick declared, “has lost its hold on the mind of our age.” In its place “the need of governmental inter- ference to promote production is admitted by economists generally” in at least several cases.22

Sidgwick was a leading utilitarian. The doctrine of utilitarianism – the idea that we should aim to maximize aggregate net happiness – had a grow- ing influence following the publication of Jeremy Bentham’s Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789). Bentham’s ideas were vigor- ously promoted by James Mill in the early nineteenth century. Although Bentham and Mill themselves judged free markets the best means to pro- mote maximum happiness, utilitarianism effectively told economists to deny preemptive status to any policy rule like laissez-faire. Instead they should pragmatically evaluate, for each proposed government activity,

21 Richard T. Ely, “Introduction” to Henry C. Adams et al., Science Economic Discussion (new york: Science Co., 1886), pp. v–x; “The Past and Present of Political Economy,” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science Second Series III (March 1884).

22 Henry Sidgwick, Principles of Political Economy, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1887), pp. 487–8. Chapter 14 discusses Sidgwick’s case for a theoretical exception to free trade.

whether its social benefits would exceed its social costs. Applying the util- itarian approach, the classical economists of the later nineteenth century, like John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick, came to regard an increasing number of activities as exceptions to laissez-faire where government likely could promote an increase in net social benefits.23

KEynES WAS noT THE FIRST To TURn AWAy FRoM LAISSEz-FAIRE IDEAS

That many economists before 1930 developed anti-laissez-faire argu- ments and supported Progressive causes may surprise those who think that professional economists have almost always favored leaving the market free, or at least did so before Keynes. Fortunately or unfortunately, the devotion of economists to the doctrine of laissez-faire has been grossly exaggerated, both for economists before the Great Depression and for economists today.24 nobel laureate (2009) and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman pro- vides an example of the first exaggeration:

Until John Maynard Keynes published The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936, economics – at least in the English-speaking world – was completely dominated by free-market orthodoxy. Heresies would occasionally pop up, but they were always suppressed. Classical eco- nomics, wrote Keynes in 1936, “conquered England as completely as the Holy Inquisition conquered Spain.” And classical economics said that the answer to almost all problems was to let the forces of supply and demand do their job.25

Keynes himself had exaggerated the situation even before 1936. In his essay

“The End of Laissez-Faire” (1926) he stated that the laissez-faire doctrine “for

23 on the role of Benthamite utilitarianism in the decline of laissez-faire ideas among British economists after Adam Smith, see Ellen Frankel Paul, Moral Revolution and Economic Science: The Demise of Laissez-Faire in Nineteenth-Century British Political Economy (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979). We give this story more attention in Chapter 7.

24 For survey evidence on the small-minority status of the laissez-faire viewpoint among economists today, and a discussion of why the viewpoint’s prevalence is often exaggerated, see Daniel B. Klein and Charlotta Stern, “Is There a Free-market Economist in the House?

The Policy Views of American Economic Association Members,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 66 (April 2007), pp. 309–34.

25 Paul Krugman, “Who Was Milton Friedman?” New York Review of Books 54 (15 February 2007), http://www.nybooks.com/articles/19857. It is difficult to square this depiction of Keynes as a pioneering critic of free-market economics with Krugman’s more recent statement “the right has always seen Keynesian economics as a leftist doctrine, when it’s actually nothing of the sort.” Krugman, “Bombs, Bridges, and Jobs,” New York Times (30 october 2011),