國立臺灣大學文學院語言學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Linguistics College of Liberal Arts

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

現代繪畫中文本性之認知多模態探討

“Textuality” in Nonrepresentational Modern Western Paintings: A Cognitive Multimodal Exploration

陳馨妍 Hsin-Yen Chen

指導教授:蘇以文 博士 Advisor: Lily I-Wen Su, Ph.D.

中華民國 105 年 6 月 June 2016

致謝

音樂學、藝術史、語言學……是誰把這三個可能被共享結構連結 的系所,擺在同一棟小小的校園建物裡呢?接近它的那刻,心跳 都要停止。那是宿命的一刻。無庸置疑地,渺小而有限的我正走 向我所無法想像的龐大複合性整體。

快從美術系畢業而剛考上語言所的我,初訪樂學館後寫下了這些。當時就很 想知道,繪畫是否像語言一樣擁有認知的規律?於是為這本論文埋下了種子。

謝謝蘇以文老師、呂佳蓉老師、張正仁老師擔任我的口試委員,為我點明論 文修改的方向。

謝謝台大語言所,特別是我的指導教授蘇以文老師,以無窮的愛心、耐心與 智慧支持我,讓這株跨領域的異花能夠順利發芽。謝謝江文瑜老師、宋麗梅老師、

馮怡蓁老師、呂佳蓉老師、謝舒凱老師、李佳霖老師、劉德馨老師賜予我充實的 知識洗禮,並不時勉勵我。這些日子,也謝謝美玲助教、嘉蘭姐與白姐從不間斷 的付出。

謝謝北藝大美術系,特別是張正仁老師、曲德益老師、陳世明老師、趙宇脩 老師、陳愷璜老師、劉錫權老師、梁晉嘉老師、賴九岑老師、潘娉玉老師、張乃 文老師、簡子傑老師,與美術系的同窗。沒有那些創作的磨練,就沒有這本論文。

謝謝台大藝史所的陳葆真老師、台大歷史系的許雅惠老師對我的研究提供寶 貴的意見,以及台大藝創課的謝宏達老師和同學們與我聊畫。謝謝科技部的補助,

讓我能出國參加學術會議。更謝謝 IACS 2014 和 CLDC 2016 的籌辦人員和有緣相 識的各國學人們,在討論中讓我進步。

謝謝一起 meeting 的國樹、書珮、承諭、婉如、彙傑、學旻。除了對我的研究 貢獻建議,在生活上也總是很關照我。謝謝你們。我永遠以 NTU COPRA 為榮。

謝謝在各方面慷慨協助我的所友們:萱芳、孟賢、瑜芸、尉賢、玥彤、聖富、

靜琛、宗榮、純睿、昱志、奕揚、星辰、盛傑、安婷、姿妤、伯雅、靖瑋、智堯、

怡馨、翔宇、慈紘、茹涵、珮瑜、伶蓁、宇喬、怡安、柏緯、郁文、亦萱、湯苓、

景瑄、榕陞。我很幸運能與你們共度充實的碩班生活。

謝謝世蓉、宗玲、慧中、廷州、慈、繹栴、睦懷、映潔、薔、侑儒、青豪、

侑辰、宇晨,以及每一位替我加油的舊識。疲憊的時候,謝謝你們鼓勵我。

謝謝爸爸、媽媽、哥哥、文鳥。一路上,再辛苦,是你們的愛讓我能夠堅持。

這本論文獻給畫畫的人。

謝謝你們為世界開拓視界,用圖畫寫下數不盡的精彩言說。

摘要

本研究透過認知語言學的理論與多模態的分析方法,探索非再現性西洋現代 繪畫的文本結構,檢測其中是否存在規律的文法象似性。許多學者將象似性視為 極具代表性的文本特徵,為自然語言的重要結構規律之一,存在於多種文類中,

包括詩文(Hiraga, 2005)與科學寫作(Halliday, 1990)。美中不足的是,如此重要

的文法特徵目前很少在語言以外的模態中討論。為回應理論空缺,我們將多模態 的文本納入象似性的認知探討。同時,為補足當前的認知研究甚少系統性分析表 述意圖與創作形式皆高度自主、不受限作畫傳統或視覺參照物的現代繪畫,而多 聚焦於應用取向、圖文比例較為平均的多模態文類探討,本研究取樣最具代表性 的 90 張非再現性西洋現代繪畫,分為具象、半具象與抽象三組樣本,一一檢驗其 象似性結構規律。

我們的模型融合並擴充了 Hiraga (2005)與 Kress and van Leeuwen (1996)的理論,

適於分析繪畫的文本結構,並能涵蓋畫作與畫題的多模態混和(Blending)效應。我 們的結果顯示,結構性的象似性 (Diagrammatic Iconicity)貫穿三種風格的繪畫樣本,

是所有樣本都共享的文本特徵。我們也發現前人尚未觀察到的現象:在資訊結構 的象似度上,非再現性的現代西洋繪畫文本和表達性的語言文本、應用類的多模 態文本擁有迥異的規律原則。

本研究的貢獻有二。其一,我們以跨領域方法示範了象似性在視覺化文本中 的分析,並證實非再現性西洋現代繪畫殊異於其他較常被討論的視覺化文類。其 二,我們找到了繪畫樣本中共享的結構性表徵。以此而論,非再現性西洋現代繪 畫文本確實具備高度符合認知規律的文本結構。透過本研究,我們將原本侷限於 語言模態的討論與檢測,延伸至高度視覺化的多模態文本中。即使是風格各異、

形式自由的前衛藝術類視覺文本,也擁有認知導向的文本性規律。非再現性西洋 現代繪畫確實能被視作一種文本性穩定的多模態文類,以象似性為基礎,符合 Halliday (1990)所定義的文本真實性。

關鍵字:

多模態; 肖似性; 文法隱喻; 認知語言學; 現代繪畫; 非再現性藝術

Abstract

This study investigates the “textuality” of modern Western paintings from a Cognitive Linguistic viewpoint. We focused on the examination of nonrepresentational Modern Western paintings, ranging from the figurative to the abstract, and studied how these paintings are arranged structurally. Specifically, we would like to see whether iconicity, an essential principle of linguistic grammar, could be found in the selected paintings.

To find out, we combined the methodologies by Hiraga (2005) and Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), and proposed a model multimodal in nature. Our results show that principles of Diagrammatic Iconicity, which structurally shape the textual flows of the paintings, are the cognitive principles guiding our selected painting samples. Moreover, it is found that the textuality of nonrepresentational modern Western paintings, which is highly poetically expressive, can be uniquely distinguished from the visual texts

previously studied, which are mostly applied and commercial-in-nature. This

transdisciplinary thesis therefore highlights how cognitive principles interact with the compositions of multimodal texts. Most importantly, nonrepresentational modern paintings could be cognitively viewed as an entrenched text, “grammatically” arranged by various layers of Iconicity, fulfilling a ‘reality of text’ (Halliday, 1990).

Keywords:

Multimodality; Iconicity; Grammatical Metaphor; Cognitive Linguistics; Modern Western Paintings; Nonrepresentational Art

Table of contents

致謝 ii

摘要 iii

ABSTRACT v

TABLE OF CONTENTS vii

LIST OF FIGURES ix

LIST OF TABLES xi

CHAPTER 1 TEXTUALITY AND PICTORIALITY 1

1.1 Background of study 2

1.2 Purpose of study 5

1.3 Organization of study 6

CHAPTER 2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 7

2.1 Iconicity and grammar 7

2.2 Iconicity and Grammatical Metaphors 9

2.3 Iconicity and textual flow 13

2.4 Modern Western paintings as autonomous pictorials 17

CHAPTER 3 A COGNITIVE MULTIMODAL METHODLOGY 19

3.1 Adopted models 19

3.2 Data 2 1 3.3 Analysis procedure 25

3.3.1 Preliminary: Figures and titles 25

3.3.2 Examination 1: Iconicity in Grammatical Metaphors 31

3.3.3 Examination 2: Iconicity in Information Flow 39

CHAPTER 4 GRAMMATICAL ICONICITY IN PAINTINGS 41

4.1 Grammatical iconicity in figurative paintings 42

4.2 Grammatical iconicity in semi-figurative paintings 45

4.3 Grammatical iconicity in abstract paintings 48

4.4 Summary of results 51

CHAPTER 5 TEXTUAL FLOW IN PAINTINGS 54

5.1 Textual flow in Figurative paintings 54

5.2 Textual flow in Semi-figurative paintings 57

5.3 Textual flow in Abstract paintings 58

5.4 Summary of results 60 CHAPTER 6 TEXTUALITY IN NONREPRESENTATIONAL MODERN

6.1 Modern paintings and multimodality 63

6.2 Textual patterns and iconicity in nonrepresentational modern paintings 65

6.3 Modern paintings as entrenched texts 75

6.4 Concluding remarks 78

REFERENCES 80

APPENDIX 1 83

APPENDIX 2 86

List of figures

Figure 2.1 Kress and van Leeuwen (2006:179) 15

Figure 3.1 The birth of liquid desires 27

Figure 3.2 Figure zones of The birth of liquid desires 27

Figure 3.3 Character and bird 27

Figure 3.4 Figure zone for Character and bird 27

Figure 3.5 Number 32 27

Figure 3.6 Figure zone for Number 32 27

Figure 3.7 The slave market with the disappearing bust of Voltaire 30

Figure 3.8 Portrait II 30

Figure 3.9 Out of the web 30

Figure 3.10 The Persistence of Memory 37

Figure 3.11 Woman and bird at sunrise 37

Figure 3.12 Swans reflecting elephants 37

Figure 3.13 Woman and bird in the night 37

Figure 3.14 The madonna of port lligat 37

Figure 3.15 The day's awakening 38

Figure 3.16 The spectre of sex appeal 38

Figure 3.17 Woman and birds in the night 38

Figure 3.18 Blue poles 38

Figure 3.19 Soft construction with boiled beans-premonition of civil war 38

Figure 3.20 Character and bird in the night 38

Figure 3.21 Composition with pouring ll 38

Figure 4.1 The lugubrious game 44

Figure 4.2 SALIENT zone 44

Figure 4.3 MARKED zone 44

Figure 4.4 SEMANTIC RELEVANCE 44

Figure 4.5 Characters and birds rejoicing at the coming of night 47

Figure 4.6 SALIENT zone 47

Figure 4.7 SEMANTIC RELEVANCE 47

Figure 4.8 MARKED zone 47

Figure4.9 Gray 50

Figure 4.10 SALIENT zone 50

Figure 4.11 MARKED zone 50

Figure 5.1 The persistence of memory 56

Figure 5.2 New info zone 56

Figure 5.4 Convergence 59

Figure 5.5 Applicability of compositional principles (Kress et al. 1996) in the current corpus 61

Figure 6.1 Modern paintings as multimodal texts 64

Figure 6.2 Patterns of New Information zones in the figurative group 66

Figure 6.3 Patterns of New Information zones in the semi-figurative group 66

Figure 6.4 Patterns of New Information zones in the abstract group 66

Figure 6.5 Patterns of GI in the figurative group 69

Figure 6.6 Patterns of GI in the semi-figurative group 69

Figure 6.7 Patterns of GI in the abstract group 69

Figure 6.8 Textual flow formed by GI patterns in the figurative group 72

Figure 6.9 Textual flow formed by GI patterns in the semi-figurative group 72

Figure 6.10 Textual flow formed by GI patterns in the abstract group 72

Figure 6.11 Taxonomy of Iconicity in Nanny and Fischer (1999) 74

List of tables

Table 3.1 Analysis aspects 40

Table 4.1 Grammatical iconicity for The lugubrious game 45

Table 4.2 Grammatical iconicity of Characters and birds rejoicing at the coming of night 48

Table 4.3 Grammatical Iconicity for Gray 50

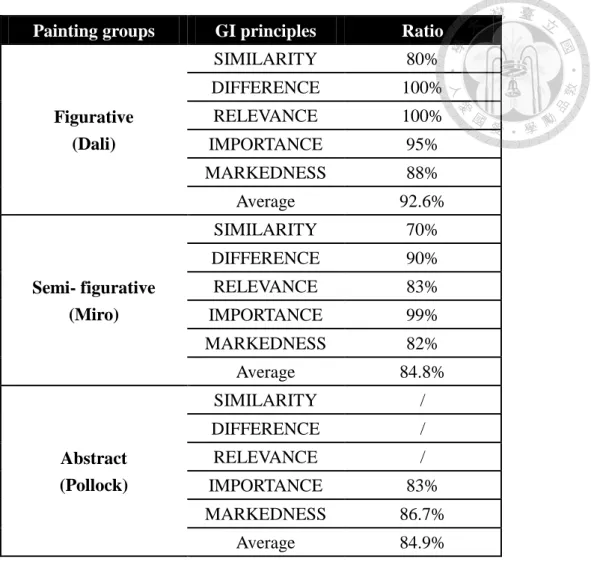

Table 4.4 Applicability of GI in painting groups 52

Table 5.1 Textual composition of The persistence of memory 56

Table 5.2 Textual composition of Characters in the night 58

Table 5.3 Textual composition of Convergence 59

Chapter 1

Textuality and pictoriality

“Graphicality is inextricable from textuality.”

– Morris Eaves (2002:99)

This thesis explores the textual patterns of a highly autonomous visual genre, modern Western paintings that are nonrepresentational. Despite its expressive autonomy, this visual genre has not been systematically investigated in cognitive multimodal studies. In this thesis, we will examine whether this particular visual genre is regularly structured, resembling the textual patterns of verbal art.

We exclusively focus on the examination of iconicity amid a collection of selective paintings: Iconicity is a fundamental textual trait of expressive or poetic texts (Jakobson 1960; Hiraga 2005), and also considered a crucial principle of the grammar of natural language (Halliday, 1990). In this chapter, we will briefly sketch the background of this study.

1.1 Background of study

Grammatical patterns, in the eyes of cognitive linguists, are seen as mirroring general cognitive operations (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Geeraerts 2006). In particular, cognitive operations intertwined with vision are found notably pervasive in linguistic grammar. Over the decades, the attention on the visual nature of linguistic grammar has grown, and termed as “the pictorial turn” in postmodern textual studies. Stockwell (2005: 6-7), notably, claims that we “urgently need better understanding of the visual elements of textuality: What images are, and how they mean. Textual studies must learn to carry the full weight of its claims to interdisciplinarity.”

As a vivid example, Langacker (2002) emphasizes the intertwining status of grammar and visual symbolicity. In promoting the idea of “grammar as image”, Langacker (2002:12) states that “(g)rammar provides for the structuring and

symbolization of conceptual content, and is thus imagic in character.” To Langacker, imagery not only serves as an essential feature of figurative expression, which is intuitively true, but also stands as a foundation of grammatical structure.

The symbolic nature of grammar is also noted to be particularly foregrounded in the structure of poetic texts (Jakobson 1960). Jakobson believes that verbal art could be best transmitted to the addressee, because it foregrounds certain linguistic functions and grammatical characteristics. In the same vein, Hiraga (2005) analyzed Japanese poetry,

and generalized a set of recurring grammatical patterns that govern the poetic structures.

In Metaphor and Iconicity, she demonstrates that Japanese pictorial poems and verbal poems alike are richly embedded with visually-symbolic grammar, especially cases of form-meaning alignments.

Via extracting the visually symbolic basis of poetic grammar, the noted cognitive linguistic effort so far outlines the way we improvise creative written texts. However, while the symbolic nature of linguistic grammar assured, the reversed remains far less explored. Few studies have systematically explored the structuring principles of expressive visuals, despite their constant cultural presence and massive size since the era of Cave Painting.

In recent years, it is indeed the case that the rise of multimodal researches raises the importance to study texts involving the interplay of words and pictures (Forceville, 2006). O’Toole (1994), exclusively, has generated a Functional Semiotics methodology, focusing on the categorization of systems and functions in artistic text, including

painting, sculpture, and architecture. While his semiotic model appears promising to the current research interest, it is nevertheless based upon single artistic instances, without a systematic exploration of the “textuality” across visual data.

In short, the inclusion of visual data in an artistic context remains scarce

comparing to the well-explored case of linguistic texts. In addition, artistic visual texts

have not yet been explored concerning their underlying textual grammar, despite the semiotic and multimodal models contributed. Similar concerns have been brought up by Johnson (2007:207):

“The idea that only words can have meanings ignores vast stretches on the landscape of human meaning-making. It leaves out anything that cannot be linguistically encoded (…) On this view, the last place one would look for meaning is in the arts.”

And also (2007: xiii):

“Art matters because it provides heightened, intensified, and highly integrated experiences of meaning, using all of our ordinary

resources for meaning-making;”

To date, we are still unable to empirically support, with the same extent of confidence Cognitive linguists hinted the visual essence of linguistic grammar, that paintings are too structurally arranged via the textual principles shared by verbal art. The lack of systematic research to the cognitive grammar to artistic visuals remains a theoretical gap.

In response, this thesis investigates whether paintings are governed by a regular set of textual patterns, and being more than just a rhetorical metaphor lacking structural grammar, as commented in Kennedy (1982):

“Pictures do not have verbs or nouns. They do not have tense structure. Hence, they cannot make claims. Hence, they are only metaphors in a sense of metaphor that needs to be firmly hedged here.”

1.2 Purpose of study

We exclusively focus on one of the most expressively autonomous visual texts,

nonrepresentational modern Western paintings. These paintings are not mainly created to faithfully represent real-world referents. With the expressive freedom, these paintings are not only highly poetic in meta-function, but also extremely unrestrained in creative forms.

The following is our core research question: Do nonrepresentational modern Western paintings possess a regular textuality? Specifically, we would focus on the principle of textual iconicity, which is so far discussed mainly in the linguistic mode. As supported (Jakobson 1960; Hiraga 2005), the grammar of poetic texts greatly involves the principle of iconicity, as it is “a manifestation of the motivated nature of the linguistic sign” (Hiraga 2005:14), fundamentally structuring linguistic grammar in general (Halliday, 1990), constituting ‘a textual reality’.

According to Halliday (1990), iconicity in texts is fulfilled by 1) the iconicity of

grammatical metaphors and 2) the iconicity of information flow. Based on the above, our research question could be further stated as a three-part inquiry:

1) Are nonrepresentational modern Western paintings structured by the iconicity of grammatical metaphors?

2) Are nonrepresentational modern Western paintings structured by the iconicity of information flow?

3) According to the combination of (1) and (2), do nonrepresentational modern Western paintings in general possess a “textuality” dictated by iconicity?

As a side observation, we would also observe if the adopted cognitive linguistic philosophy could be applied to the analysis of paintings. If no, a modality-exclusive explanatory power of cognitive linguistic theories would be hinted. If yes, cognitive linguistics serves as a promising framework for analyzing a spectrum of data, including the more radically non-linguistic case of autonomous, non-conventional pictorials.

1.3 Organization of study

In the following chapter, we will review the theoretical bases for this study. In chapter 3, we propose a multimodal methodology for analyzing the textuality of paintings. In chapter 4 and 5, analyses and results of the examinations are displayed. A discussion of our overall findings is presented in chapter 6, before the thesis reaches its finale.

Chapter 2

Theoretical background

The current chapter outlines the theoretical bases for this study. We will review the notion of iconicity, which serves as a crucial principle directing the textuality of verbal art. Moreover, we will review Halliday’s (1990) definition of ‘textual reality’ based on the two facets of iconicity. We will additionally review the related models on

grammatical iconicity (Hiraga, 2005) and multimodal text compositions (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). Finally, we will briefly outline some basic features of modern Western painting.

2.1 Iconicity and grammar

Iconicity refers to the alignment of linguistic form and linguistic content, contrasting the notion of arbitrariness. In a Saussurian tradition, the relationship between signifiers (form) and signified (content) is considered arbitrary, in which there is not necessarily a motivation between the correspondence of form and meaning. However, as reviewed by Hiraga (1994; 2005), Jakobson (1971) considers the opposite on the basis of the

Peircean sign trichotomy (1955 [1902]). Signs are divided into icons, indices and symbols based on levels of resemblance to their corresponding referents. Icons are the

most object-resembling signs, and symbols being the most arbitrary.

Icons, the most iconic or non-arbitrary signs, are further divided into images, diagrams, and metaphors by Peirce. Images, diagrams and metaphors together

constitute a hierarchy of iconicity. From images to metaphors, there is an iconic continuity based on similarity principles of “mimicry (quality)”, “analogy (structure)”

and “parallelism (association)” (Hiraga 1994; 2005). In Peircian semiotics, the three are also termed as semiotic “firstness”, “secondness”, and “thirdness”, accordingly.

In Halliday (2002 [1990]), a functional analysis to scientific writings is presented.

In his writing, Halliday mentions the intersection of science and verbal art, in which scientific writings are “constituted out of the impact between scientific and poetic forces of meaning.” (2002 [1990]:177). It is therefore claimed that the grammar of verbal expressions is often iconic in nature, which constructs “the total reality in which we now live, a reality consisting of semiotic entities in a periodic flow of information”

(2002 [1990]:175).

The reality of textual grammar here consists of two kinds of iconicity: Iconicity in

‘semiotic entities’, and iconicity in the ‘periodic flow of information’. In the following,

we will outline both facets of textual iconicity, and their theoretical extension to the analysis of multimodal texts.

2.2 Iconicity and Grammatical Metaphors

In Halliday (2002 [1990]:175), the ‘iconicity in semiotic entities’ particularly refers to cases of ‘nominal packages’. It is the process of compressing a verbal event into the form of nouns, which is also called “nominalization”. In English, this is often put into practice by adding certain suffixes at the end of the verb stem, such as the

productive –tion. Therefore, as an example, to nominalize is an action, whereas

nominalization implies a noun-like ‘semiotic entity’. When a verbal event is packaged

as a noun, it could then be processed in speech and in our mind as moveable entities, or objects. By the change of grammatical forms, we think of the same concept in different ways-- from the more dynamic “action” to the more entity-like and compacted idea of an “object”.

From action to object, this particular process is defined as an instance of

grammatical metaphor in Halliday (1994a). Put simply, grammatical metaphors could

be identified when the grammatical form of an expression suggests its perceived

meaning. It is metaphorical, because there is an analogical alignment between form and meaning. The scope of grammatical metaphors could be instantiated at the level of phonology, or at the level of morphology and phrase. However, morpho-syntactic examples of nominalization, or nominal packages, remain the central discussion of grammatical metaphors in Halliday’s work.

In the work of Hiraga (2005), she explores the instantiation of grammatical metaphors in Japanese poetry, including verbal poems and pictorial poems, extending the analysis scope of grammatical metaphors to that of discourse. It is reported that grammatical metaphors plays a crucial part in the structuring of poetic texts. The intense interplay of poetic content and its grammatical arrangement co-creates the complete aesthetic meaning of the poetic discourse.

Based on her observation, Hiraga proposed a typology of grammatical metaphors (shortened as GM), a “systematic classification of grammatical metaphors” (2005:174).

The model consists of a list of non-exhausting GMs called ‘iconic mapping rules’ found in poems. The interplay of iconicity and metaphors has been highlighted, involving iconic instantiations found locally in sound-symbolism, word order, and even in the printing arrangements of pictorial poems. These iconic instances add to the

interpretations and meanings of the poems observed. Comparing to Halliday’s original idea on GM, Hiraga’s GI model has gone beyond the morpho-syntactic realizations to the level of discourse. The observed iconic instantiations “contribute to the interplay of form and meaning at the level of both text segments and text macro-structure.” (Hiraga 2005:52).

Hiraga’s GM typology consists of a set of non-exhausting iconic mapping rules

directing poetry compositions. These rules are proposed in the backbone of Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) Conceptual Metaphors, in which they describe schematic and

productive form-content alignments across poetic discourse. There are two major categories in Hiraga (2005), namely relational diagrams and structural diagrams.

On the one hand, relational diagram refers to iconicity instantiated within one comparative dimension. For instance, if some forms display similarity, and their meanings indeed display similar semantic or pragmatic characteristics, this would then identified as applying to the GM of SIMILARITY IN MEANING IS SIMILARITY IN FORM. Relational diagrams still include iconic mapping rule DIFFERENCE OF MEANING IS DIFFERENCE IN FORM.

On the other hand, structural diagrams demand structural mappings between

‘structure of form and structure of content’ (Hiraga 2005:175), so it differs from cases of

relational diagrams. For example, if some repetitive phrasal structure intensified and enriched the meaning of a text, the quantity of forms then suggests the importance of their textual meaning. This would be an instantiation of MORE FORM IS MORE MEANING, which involves a structural alignment between form-quantity and meaning quality. Structural diagrams still include TEMPORALITY IS LINEARITY (e.g. when the linear placement of the expressed ideas aligns with their event order), and

SEMANTIC RELEVANCE IS CLOSENESS. Semantic relevance, in Hiraga

(2005:180)’s term, refers to expressions that are “semantically closer”. In her linguistic model, it is often the case that lexical items that are placed closer express stronger relevance, or stronger, more affirmative pragmatic effect.

Besides the mentioned rules, Hiraga also observes some iconic mappings that are linguistic or cultural-specific, such as ones found in linguistic frozen expressions, or in the unique grammar of politeness in Japanese culture. While the specific principles may seem distant from our multimodal exploration, other iconic rules, in fact, are found applicable in a pilot study on painting and iconicity. In Chen and Su (2014), 5 out of the 7 mentioned iconic mapping rules are found to be applied in a mixture of 120 matured paintings done by Spanish artist Miro.

It is noted in Hiraga (2005:226) that the issue of iconicity remains unexplored in the area of non-verbal communication. Based on the work of Hiraga (2005) and Chen and Su (2014), this model concerning the interplay of metaphor, iconicity and poetic expressions, serves as a promising starting point for the current exploration.

2.3 Iconicity and textual flow

Another line of “textual reality”, besides the iconic instantiation of grammatical metaphors, is defined by Halliday as the iconic flow of textual information, which is constructed by Information values, i.e. the relative idea of Given or New information of a text. Specifically, he states:

There is a movement from a given Theme (…) to a rhematic New (…) (T) his movement in time construes iconically the flow of

information.

(Halliday 2002 [1990]:175)

This definition of textual reality is based on Halliday’s theory on textual pattern.

As claimed, the clausal structure in English consists of two intertwined information lines, namely the couplet of Theme and Rheme, which is speaker-oriented, as well as Given and New, which is listener-oriented. The two information lines are simultaneous in nature: As the Theme and the Rheme realized via the “segment position” in a clause, the Given and the New accompany prosodic contrasts. Therefore, it is possible that the

two interrelated systems combine, resulting in an overlap of the Theme and the Given, together serving as the starting information or “ground” (as contrary to “figure” in

gestalt psychology) of an expression.

For instance, in the sentence I think it looks great, the front part I think serves as

expression. Meanwhile, the part it looks great remains more “unpredictable” and “news worthy”, which expresses the speaker’s evaluation. Without this part, the sentence fails to give out its essential “punch line”. It could thus be counted as the Rheme, or the New of the sentence. In this case, the overlap of Theme and Given, as well as that of Rheme and New, applies to Halliday’s definition of a default, or “unmarked” instance of textual information. The proceeding of a text, then, is made possible by the spatial as well as meaningful tension between the Given and the New. This is one of the core principles that constitute the grammar of natural languages (2002 [1990]:173). The default

arrangement, as noted, consists of a Theme or Given information at the sentence initial, and a follow-up of Rheme or New. Concerning the writing directionality of most Western languages, it is often the case that such “default” information flow of linguistic texts lines up from the left, to its right-branching sentential parts:

Halliday’s Information system is extended into the realm of the multimodality.

Specifically, social semioticians Kress and van Leeuwen (1996; 2006) studied the

compositional pattern of visual texts in general. They have proposed a general pattern, or ‘visual grammar’, across most western visual layouts. The proposed diagram for

visual compositions is as illustrated:

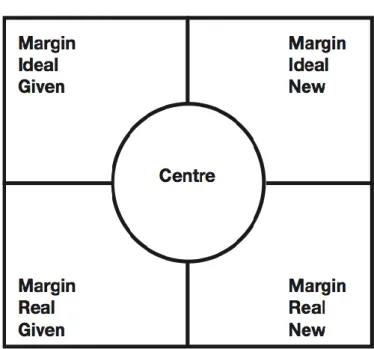

Figure 2.1 Kress and van Leeuwen (2006:179)

This diagram predicts the general textual composition of visual materials in the context of Western cultures: From the left to the right, there is a pattern of Given to New;

from the top to the bottom, there is a pattern of Ideal to Real. It is claimed that a

Given-New information pattern could be observed across most Western visuals, which is postulated to be influenced by the writing-directionality in most Western languages,

following Halliday’s view. Usually, there would be a left-placing of Given information, while the more “surprising”, unexpected content featured at the right, and labeled as the

New. The circle in the diagram stands for the sometimes centralized visual focus observed. Kress and van Leeuwen claimed that a centralized visual composition would

still follow the overall tendency suggested by this diagram, which is exclusively designed for the two-dimensional nature of pictoriality.

Besides the criteria of Ideal-Real and Given-New, which are based on Information values of in-text pictorial areas, Kress and van Leeuwen mentioned two alternative

principles which also play a role in influencing visual compositions. The two principles are Saliency and Framing, respectively. While Saliency refers to the perceptually salient qualities of a visual, which is often created by stronger contrast in color, tone, size or sharpness of pictorial compositions (Kress and van Leeuwen 1996:212), Framing refers to the compositional separation of textual areas, which is an important feature of applied visual layouts.

Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996; 2006) model, while inspiring in nature, consists of a mixture of visual genres, ranging from composite pictorials such as magazine layouts, films, photography, picture books, and single pictorials like paintings, graphic designs, and advertisements. The realm of paintings has not been systematically focused on in this model. This gap prompts the current need to study modern paintings in a systematic way. In the following section, we will briefly introduce the basic

characteristics of the set of pictorials in wait for systematic discussion, and with the utmost essentialness to be involved in cognitive multimodal studies.

2.4 Modern Western nonrepresentational paintings as autonomous pictorials This study specifically focuses on a selection of nonrepresentational modern Western paintings. According to Luhmann (2000), after the Renaissance, painters in the Western world slowly gained their autonomous in art creation, shedding away the traditional burden, for instance to paint for religious duties. Since the late 19th century to the early 20s, the outburst of artistic movements such as Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism opened up a brand new extent of artistic freedom, leading to the heydays of Modern Art.

Art movements mushroomed, each striving to defy the traditional ways of depiction.

The paintings created in the Modern Art era, which strongly coincides with the

blooming of the mentioned artistic movements around 1900 till the late 70s (concerning the life spans of the featured artists), revolutionized the way we see and think visually.

Besides its expressive autonomy, modern Western paintings are also comparatively autonomous due to their default forms: They are almost always presented on the flatness of a rectangular canvas, as commented by Schapira (1969):

“We take for granted today as indispensable means the rectangular form of the sheet of paper and its clearly defined smooth surface on which one draws and writes (…) the smooth prepared field is an invention of a later stage of humanity.”

(Schapiro 1969:9)

In a sense, the somewhat conventionalized form of modern painting pieces strengthens their independence. They are considered single pieces, ready to be displayed or

purchased, rather than serving as an illustration for other communicative purposes. We could say that the autonomy of a modern painting is co-shaped by the “conventionalized”

use of canvases. Such materiality distinguishes “works of art” away from “crafts”, such as pictures painted on vases, walls or furniture. Summing the above, modern paintings, especially ones that originated in the mentioned contexts (20th century Western modern Art movements), are ideal to be seen as independent “texts” conveyed in a pictorial mode. This stands as the basis for our assumption. In the next chapter, we will introduce how we examine these paintings via a cognitive multimodal approach.

Chapter 3

A cognitive multimodal model

This chapter introduces a methodology for textually analyzing paintings. Our model combines Hiraga’s (2005) grammatical metaphors (GM) with Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996) visual compositional principles, serving to analyze paintings in a multimodal approach. We aim to find out whether non-representative paintings qualify the definition of a ‘reality of text’, and constitute a structurally-arranged text genre. The following illustrates the present methodological design, the adopted models, as well as details of data selection.

3.1 Adopted models

Iconicity remains one of the central characteristics of linguistic grammar, not only in the figurative case of poetic texts (Jakobson 1960; Hiraga 2005), but also in scientific writings (Halliday, 1990). This phenomenon is nonetheless never fully explored in modalities outside language. In this chapter, we adopt related models for the exploration of iconicity to a corpus of nonrepresentational modern Western paintings.

Two foci line up in our examination of paintings. First, the existence of iconic grammatical metaphors is investigated across a spectrum of nonrepresentational

Western modern paintings via Hiraga’s (2005) model. Second, the pattern of an iconic textual flow across painting-layouts is analyzed via the semiotic model of Kress and van Leeuwen (1996).

Hiraga’s linguistic model defines and lists out instances of iconic GMs, and Kress and van Leeuwen’s visual model helps provide a working definition for the visual counterparts of GI in painting-plates. The pictorial GM in this study, then, is defined when the visual forms and the multimodal semantic cues of a painting align with each other, creating a comprehensive meaning of the whole artwork.

Some of the GMs in Hiraga (2005) could directly be mapped to the examination of pictorials in Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), for instance the GMs of form quantity, distance and similarity. As noted in 2.2, there are iconic rules that only apply to

linguistic data, such as the iconic principle on linearity, and how linguistic politeness is instantiated through the in-text distance of lexical items. These iconic rules would be excluded in this study. While the politeness issue is clearly missing in the case of

paintings, the linearity issue too needs to be “hedged” in order to fit our visual data now, as implied in Chen and Su (2014).

Instead, in the two-dimensional case of paintings, Kress & van Leeuwen’s (1996) visual-oriented model could complement Hiraga’s (2005) linguistic model, for it focuses on an overall compositional flow of paintings via a four-part diagram (Fig. 2.1), rather

than a linear one. In the aspect of textual directionality, it is more flexible and visually-oriented than Hiraga’s model. In this study, both models are adopted and adjusted in generating a method suitable for multimodal exploration.

3.2 Data

Our data consists of 90 nonrepresentational modern Western paintings created in the 20th century, including 30 figurative paintings, 30 semi-figurative paintings, and 30 abstract paintings, following the categorization in Arnheim (1969). The concepts of figurative and abstract are relative: they constitute two ends of a continuum, and could never be put in a clear-cut dichotomy. The inclusion of all styles of paintings ensures that a

comprehensive data pool is covered. Moreover, the three-group sampling expects to bring forth possible cross-group comparisons in compositional principles.

Each sampling group contains paintings created by one specifically representative painter. For the quality of the data, it is ensured that these representatives remain productive painters. The sampled paintings are selected out of three chronological painting albums of the representative artists, excluding practices of representational artwork, sketches, prints or other miscellaneous scripts. After the exclusion, the amount of samples is balanced to approximately thirty in each of the three painting groups.

The pure reality-simulative artworks are excluded. They would not constitute idealistic examples of expressive paintings since a representational intention, or restrictions bound to photography or real-world referents are involved. Instead,

nonrepresentational paintings are selected, with the pictorial contents generated via the painter’s free association. In this sense, paintings are autonomously expressive in its creation process and creative form. In the following, we will illustrate details of the sampled data.

1) Figurative painting samples: Dali

Thirty of Spanish artist Dali's paintings are representative as figurative, nonrepresentational modern Western paintings, for they are:

i. Figurative in style; the viewers can easily identify and name the painted elements;

ii. Nonrepresentational in intention, in which the painted events are mainly created via the process of free association, so they may lean closer to expressive texts rather than to real-world snapshots.

There are no abstract parts in Dali’s paintings-- every line and pile of paint constructs part of a figurative object. We can always name his painted items, even though his art does not rely on the tradition of real-life painting. His paintings thus serve ideally as our figurative samples.

2) Semi-figurative painting samples: Miro

Thirty of Spanish artist Miro's paintings are representative as being semi-figurative samples. The paintings are selected for being:

i. Semi-figurative in style: The intention of abstraction has not yet fully erased the identifiable semanticity of depicted items, and the pictorial items still carry degrees of semanticity. However, they are abstracted to some extents that demand more reading effort.

ii. Nonrepresentational in intention: While arranging non-abstract elements like human, animals, stars and birds, Miro would almost always simplify these elements. His artistic elements became so abstracted in form and

nonrepresentational in intention, that they became sign-like (Corbella, 1993).

Note that for this sampling group, possible candidates include semi-abstract styles of artwork such as ones done by Cubists. However, in most Cubists’ work, even if the depicted objects are abstracted and transformed, deliberately flattened till they stuck between figurativeness and mere abstraction, certain extents of real-world

representation are involved. To be able to select paintings that are most generative and autonomous in expressive processes, we exclude these pictures.

3) Abstract painting samples: Pollock

American artist Pollock's 30 paintings stand for ideal samples for being

“non-representation” and “abstract” modern Western paintings. His paintings are:

i. Abstract in style; the viewers cannot identify nor name any of the pictorial elements;

ii. Non-representative in intention, in which neither real-world referents nor a will

to represent objects could be found.

Pollock’s art pieces are selected due to their highly intuitive and impromptus nature

known as “action painting”. The “forms” in these paintings stand for nothing but themselves—the visual pleasure they arouse rather than any concrete referents.

The excluded candidates for this category are the abstract paintings done by the Minimalists. It is indeed the case that the inclination to feature only geometric shapes or color layers on canvases fits utmost the criterion of being nonrepresentational.

Nevertheless, minimalist abstract paintings undergo conceptual planning processes.

Even if the color-field paintings are done in an impromptu way, they do not necessarily contain the same extent of expressive intention most lyrical abstract paintings, such as ones done so intuitively done by Pollock, would have.

3.3Analysis procedure

We proposed an analysis procedure for examining the grammatical iconicity and textual flow of modern paintings. This procedure consists of three major examination steps designed based on the two models mentioned. A detailed introduction follows in 3.3.1 to 3.3.4, respectively.

3.3.1 Preliminary: Figures and titles

It is crucial to note that paintings preserve traces or processes of affordance during production, e.g. how painters physically make sense of the painting medium (paints

and textures) while they create. For every viewer alike, there is an initiative step to tell

“what is what” in a painting. After this process, the basic “happening” in the targeted

painting are more attentively viewed. Before we start our analysis, which concerns the multimodality of the current data, we will explain here how the iconic GMs and the judgment of information zones are achieved in a two-dimensional visual text. The key, we believe, lies in a mechanism which is often subconsciously applied: our instinct to the separation of figure and ground.

The notion of figure and ground has a psychological backbone: We as viewers could usually tell the attention focus of a painting, and even find such process effortless most of the time. Such attention foci are called figures in perceptual psychology, and

the rest of the painting, which is usually less-noticed and “backgrounded” in our attention, is termed grounds. The notion of figure and ground has been proposed in visual psychology and cognitive sciences:

“The figure is located inside an outline (a closed visual edge), it has a form and is more or less like an object (…) In experiments, it is more easily identified and named, more easily linked to semantic, aesthetic and emotional values.”

“The ground (…) is more or less formless, more or less

homogeneous and is perceived as extending behind the figure.”

--Aumont (1997:46)

To identify the figure zones in two-dimensional paintings is mainly a perceptual process. In figurative and semi-figurative sample groups, as the figurativeness of depicted foci mostly stand as figures, which are attention zones opposing the surrounded grounds. In the more challenging case of abstract samples, it is still possible to tell specific layers or zones of Pollock’s paintings being figures. That is to say, even the seemingly wild action paintings created by Pollock are actually

governed by the cognitive principle of figure-ground distinction. Again, this may be due to the fact that even Pollock himself would subconsciously make sense of his creation during the rapid painting process. Some zones or layers of paints thus stand out, even just slightly, over the other zones or layers of Pollock’s abstract paintings.

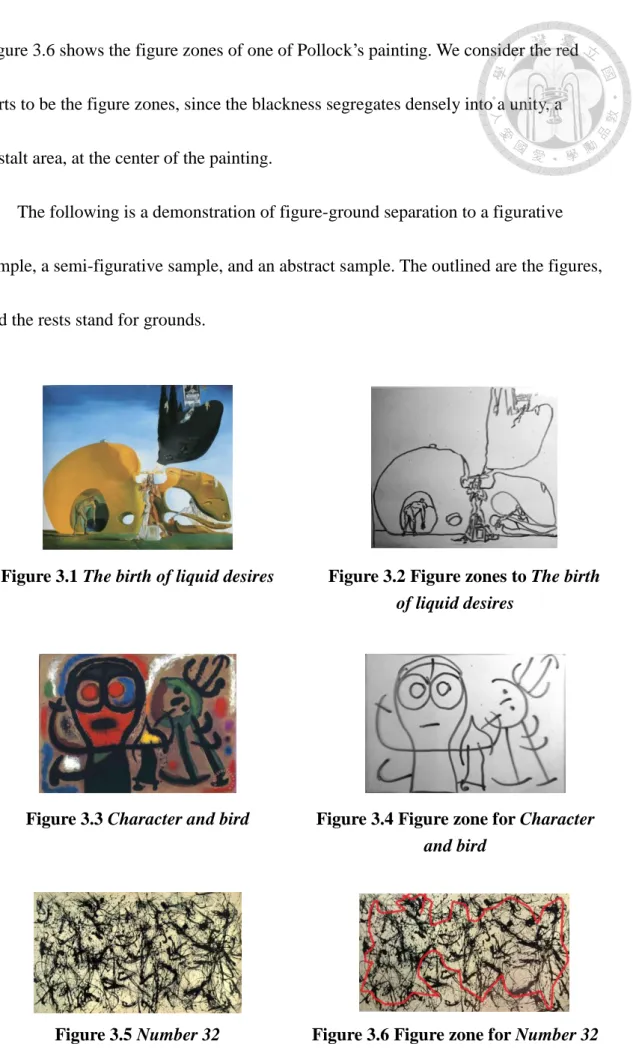

Figure 3.6 shows the figure zones of one of Pollock’s painting. We consider the red parts to be the figure zones, since the blackness segregates densely into a unity, a gestalt area, at the center of the painting.

The following is a demonstration of figure-ground separation to a figurative sample, a semi-figurative sample, and an abstract sample. The outlined are the figures, and the rests stand for grounds.

Figure 3.1 The birth of liquid desires Figure 3.2 Figure zones to The birth of liquid desires

Figure 3.3 Character and bird Figure 3.4 Figure zone for Character and bird

Figure 3.5 Number 32 Figure 3.6 Figure zone for Number 32

Besides the visual-perceptual basis, painting titles are also an essential part of the multimodal whole of an artwork. In Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), visual

representational structures are divided into two major types, namely Narrative and Conceptual (1996:56). The narratives pictorials are those that contain actions or visual

linkages between visual participants within an image, while the conceptual pictorials being ones that are more motionless, meaningful in the appearance of the visualized itself. In categorizing paintings following such a distinction, their titles serve as a helpful semantic cue other than the mere visual content presented in the paintings.

Moreover, modern paintings are created by artists with a brand new extent of autonomy over their artwork. They are pieces of work in wait for specific

acknowledgment from viewers, art critics, exhibition curators, art dealers, and even from art museums. In this respect, the titles of modern paintings constitute a crucial part of the art piece as a symbolic, multimodal, and contextualized whole. We thus co-analyze painting titles and the painted images, so that the denoted content could be more comprehensively interpreted.

In our three sample groups, painting titles generally inform the viewers not only the expressed content, and also help trigger richer interpretation or appreciation to the painting. For instance, Dali, a skilled figure-ground reversion expert, entitled a

painting with the keyword Voltaire. In the painting, the close-up of Voltaire is formed

by the smaller outlines of three maids in black-and-white dresses. If not the title, the viewers might miss out the alternative, gestalt grasp of the Voltaire outline (Fig. 3.7).

The same title-image alignment could be commonly found in semi-figurative samples as well, such as a Miro painting entitled Portrait II (Figure 3.8). Of course, it is possible that many viewers could interpret the human figure the geometric zones in this painting indicate. Nevertheless, it is the title that more firmly fixated the

semantics to the pictorials.

In abstract paintings, particularly, it is often the case that they do not own a

semantically concrete title. Even so, the title directs us to be able to focus on the

“entity-like” status of visual Gestalts. When they accompany semantic titles, as in the

below example, the title helps greatly in hinting a certain way of painting appreciation.

In Pollock’s Out of the web (Fig. 3.9), the red zones already catch our attention in the first glimpse. However, adding in the information of the verbal cue, we are more likely to observe the vectoring that relaxes from left to right, as it matches the “out of the web” concept in the title. In this respect, painting titles appear as cognitively essential in the process of painting appreciation, serving as a more dominant interpretation within the numerous possible ones.

Figure 3.7 The slave market with the disappearing bust of Voltaire

Figure 3.8 Portrait II

Figure 3.9 Out of the web

3.3.2 Examination 1: Iconicity in grammatical metaphors

Hiraga’s (2005) set of GMs serves as our examination criteria for pictorial

MEANING. In this study, we will further examine the selected paintings by the same five GMs found applicable in Modern paintings based on Chen and Su’s (2014) pilot study. Based on these cognitive linguistic principles, we propose a set of extended working definition for the current multimodal data. In the following, we list out instances of iconic GMs defined in figurative, semi-figurative and abstract paintings.

1) SIMILARITY OF FORM IS SIMILARITY OF MEANING Hiraga (2005:177-178) defines similarity of form as a flexible range of

form-resemblance, including shared lexical elements, i.e. word affinity phenomena.

For instance, many words featuring gl- imply lightness, e.g. glitter, glisten, and glow.

In the same vein, we define similarity of form in terms of the family resemblance of shapes or outlines between figure zones done by the same artist.

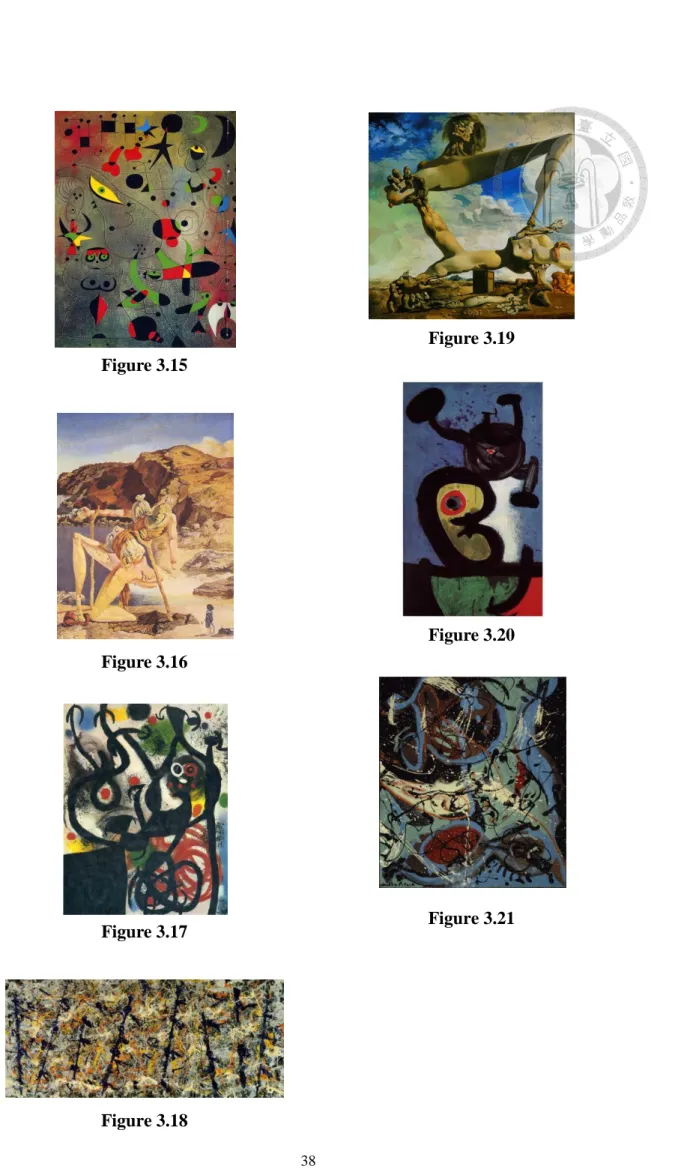

For instance, in Dali’s The Persistence of Memory (Fig. 3.10), several clocks are depicted. Even though they are twisted in different ways, the fact that they all stand for prototypical locks is unquestionable: the clocks are fully depicted with pointers, rims and clock-faces. Thus, the clocks in this painting are considered similar in form, matching their meaning similarity.

Similarly, in Miro’s Woman and bird at sunrise (Fig. 3.11), the two major pictorial elements stand for “birds”, and are arranged in similar forms. They clearly

differ from the smaller pictorial elements at the lower left, which stands for

“human”—it is, contrastingly, vertically arranged and depicted with stronger

emphasis on his body. The birds are similar in form, and similar in meaning, hence applying the GM SIMILARITY IN FORM IS SIMILARITY IN MEANING.

In abstract paintings, however, the meaning contrasts do not exist, and this GM could not be applied. There is no semanticity embedded in the pictorial elements in abstract paintings. In fact, from GM 1) to 3), the abstract group could not be defined by them.

2) DIFFERENCE IN FORM IS DIFFERENCE IN MEANING

Difference of form in Hiraga (2005) is defined based on the sharedness of lexical

components. For instance, the light-related words coined with gl- usually share nothing in common with words coined with fl-, which often suggest movement, such as flip, flit, or flap (Hiraga 2005:178). Thus, for multimodal data, we identify instance of different forms as pictorial units that clearly distinctive from each other in formal features; and usually, the distinction of pictorial forms is actively created to avoid semantic confusions.

As an example, in Dali’s Swans reflecting elephants (Fig. 3.12), the pictorial elements above water stand for swans, and their reflections became elephants. The swans and elephants are distinctive in their shapes even though they are closely placed, and are supposedly symmetrical in reality. This is an example of

DIFFERENCE IN FORM IS DIFFERENCE OF MEANING.

In the semi-figurative Woman and bird in the night (Fig. 3.13), two similarly sized pictorial units are clearly divergently formed: The upper one features thicker outlines and has no emphasis of facial parts, while the lower one clearly featuring a head and two exaggerated eyes. Thus, the bird on top and the person beneath it clear belong to two distinct denotations, and are different in form and meaning.

3) SEMANTIC RELEVANCE IS CLOSENESS

This iconic GM concerns the actual distance between pictorial items in a painting. It is similar to Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980:126-33) STRENGTH OF EFFECT IS CLOSENESS. Hiraga instantiates this GM with the below example (2005:181):

a) Mary doesn’t think he’ll leave until tomorrow.

b) Mary thinks he won’t leave until tomorrow.

The stronger iconicity of proximity in b) is created by the shorter semantic proximity in the sentence structure.

The madonna of port lligat (Fig. 3.14) is an instantiation of SEMANTIC

RELEVANCE IS CLOSENESS in our figurative samples: The animated or semantically relevant elements are placed closer, as other elements grouped at the peripheral. The two sets of elements are not randomly mixed in the painting-plate.

In a semi-figurative sample,The day's awakening (Fig. 3.15), animated characters are placed at the left-center, as other non-human elements arranged at the reams of the painting. Semantically closer elements are compressed closer.

4) MORE CONTENT IS MORE FORM

In Hiraga’s original definition, this GM refers to the effect word repetition creates in strengthening the power and rhythm of Japanese poetry. The amount (spatial size) of words matches and enhances its intended expressive effect.

In the case of images, it is reported (O’Toole 1994; Kress and van Leeuwen 1996) that some of the visual-perceptual facets would affect the vividness of pictorial parts, including size, extent of sharpness, and tonal or color contrasts. QUANTITY IS IMPORTANCE could be instantiated either by the repetition or larger size of certain figures, or by a stronger visual-perceptual saliency. In this respect, the

linguistic-based QUANTITY IS IMPORTANCE could be imported to a multimodal-based SALIENCY IS IMPORTANCE.

In Dali’s The spectre of sex appeal (Fig. 3.16), the largest pictorial element is the giant woman body at the leftward center. Its size makes it extensively eye-catching, and highlights the semantics of the title. This is an instance of MORE CONTENT IS MORE FORM, as the giant woman in this painting serves as the attention center as well as the textual focus of the multimodal piece.

Sometimes, the importance of content would be reflected both in the size of the targeted form, and the number of it. In Miro’s Woman and birds in the night (Fig.

3.17), the largest elements are the “faces” entangled at the center area. Their size and their coupling status declare and strengthen their textual importance.

Similarly, in abstract paintings, bigger sized gestalt shapes occupy more textual space, therefore a more protruding textual importance. Sometimes, both sizes and elemental numbers multiply the importance. A Pollock painting called Blue Poles (Fig.

3.18) is a vivid example.

5) MARKED MEANING IS MARKED FORM

Linguistically speaking, the markedness of form contrasts a default, more basic linguistic arrangement. For example, English past tense is often featured with overt semantic markers (Hiraga 2005:184), thus considered more marked comparing to their present simple tense counterparts.

In our multimodal analysis, the markedness of form would be defined according to the visual facets of perceptual saliency and its meaningful status within the

painting-text. For instance, in Dali’s Soft construction with boiled beans-premonition of civil war (Fig. 3.19), the redness captures our attention in two ways: Its bright red

color and its denotation, a male private part, together serve as a more tabooed area of this painting. It is special in depicted form and in its textual meaning, thus applying the GM MARKED MEANING IS MARKED FORM.

In our semi-abstract samples such as Character and bird in the night (Fig. 3.20), it is noticeable that the bright color areas group together at the lower right area of this painting. This attention group wraps around the characters in the middle, and helps direct our eyesight to linger about. Also noticeable is the redness at the lower right corner: It is not as bright as the white and yellow at the center. However, it attracts out attention to the specific area, in which an up-pointing curve is hinted. This leads back to the vectoring loop, or view cycle, towards the center part. In this respect, the

redness in the painting plays a special role of attention attracting and view path aiding.

It stands out, distinctive aside its neighbors, and so fulfilling the definition of

“markedness” in this painting. This is an example of MARKED MEANING IS

MARKED FORM.

Finally, this GM could also be defined in abstract cases. In Composition with pouring ll (Fig. 3.21), the round gestalt is special in this abstract painting, because it is

the only round spot. It fixates out attention, and helps direct a viewing path in this painting. Textually speaking, it is both special in shape and in function. This applies the GM of MARKED MEANING IS MARKED FORM.

Figure 3.10

Figure 3.11

Figure 3.12

Figure 3.13

Figure 3.14

Figure 3.15

Figure 3.16

Figure 3.17

Figure 3.18

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.20

Figure 3.21

Combining these visual aspects, as well as the diagrammatic rules, our working definition of GMs in paintings consists of mappings of VISUAL FORM to that of TEXTUAL MEANING.

3.3.3 Examination 2: Iconicity in Information Flow

For the second part of examining whether paintings constitute ‘a reality of text’, the existence of a flow of textuality is tested among the sampled. In Hiraga’s

Grammatical Iconicity model, the particular rule demands a linear modality trait, and is found non-applicable in two-dimensional pictorials (Chen and Su, 2014). We will compensate this non-applicability by adopting Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996) visual compositional diagram outlined in 2.4, examining an underlying textual flow in our selected paintings.

We specifically focus on the contrast of Left and Right, because it is where a comparison of linguistic grammar and visual pattern (both in Western languages) could be conducted. Hence, we will mainly observe the horizontal textual flow dictated by Given and New, following Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996) four-part diagram, aided by the compositions of Saliency and Framing. The overall aspects are shown inTable 3.1:

Steps Source Target Alignment Visual forms Textual meaning Iconicity

Preliminary Figures Semantics/ title --

Examination 1

Similarity Shape Similarity

Iconicity in Grammatical

Metaphors Difference Shape Difference

Closeness Distance Semantic relevance

Saliency

Size

Importance Color

Tone Sharpness

Markedness

Size

Markedness Color

Tone Sharpness

Examination 2

Composition

Info value

Iconicity in Information flow Saliency

Framing Table 3.1 Analysis aspects

To recap, in the current multimodal methodology, we combine Hiraga (2005) and Kress and van Leenwaun (1996). The steps include a pinning down of painting semanticity via the help of panting titles, an identification of main figures, an analysis of grammatical iconicity, and finally an examination of the textual flow, or

directionality, of the painting. Our analyses are presented in the following chapters.

Chapter 4

Grammatical iconicity in paintings

“I believe that perceptual form is the strongest, most indispensable means of communicating through works of art. Why should form exist, were it not for making a content readable?”

--Arnheim (1982)

In this chapter, we focus on answering this question: Are nonrepresentational modern paintings in general structured by grammatical metaphors? To find out, we combined the cognitive linguistic model of grammatical iconicity (Hiraga, 2005) as well as criteria for visual saliency (Kress and van Leenwen, 1996).

A total of five grammatical iconic mappings are examined in each painting.

Specifically, the titles of the paintings are analyzed in order to ensure a multimodal meaning of the pieces; also, as explained in Chapter 3, the figure zones serve as the major visual forms analyzed in this study. In the following, the examination of all three painting groups is shown separately in 4.1 to 4.3.

4.1 Grammatical iconicity in figurative paintings

In the Figurative group, the five aspects of iconic grammatical metaphors are generally found highly applicable.

For instance, in Dali’s The lugubrious game (1929) (Fig. 4.1), the theme

suggested by the title could be mapped to the major “figure zone (similarly conveyed in an obvious human shape). The happening of the “game”, as entitled, matches the gestalt area in the middle, which is salient in size, sharpness effect created by depicted details, color and total richness. The combination of these visual factors together creates a highly grammatical iconic status of this painting, in which the saliency of visual forms enhances the textual meaning (Fig. 4.2).

It is also noticeable how the iconic rule MARKED MEANING IS MARKED FORM applied in this painting (Fig. 4.3). Comparing to the other parts of the picture, the blue area shaped like branches (at the centralized bottom) appear protruding—it is painted with bright blue, with is particularly high in color saturation in this picture. It may not be as eye-catching as the SALIENT zone, for it shares a similar color tone to the “ground” layer (the blue sky); also, it is not huge comparing to the main figures.

In the aspect of visual unusualness, even if it is not “news worthy” in semantics, it is perceptually marked. In fact, we could more effectively follow the “strangely

brightened” blueness and further notice to the right of the painting, in which the figure

zone consists of two people with blood. The redness of the blood attunes with the neighboring part, a depiction of a man’s buttock, which is also tainted with blood. The blood is only a detailed part of this painting, yet its visual-perceptual trait as well as its textual symbolicity remains special. Given these reasons, we will mark the zone circling the bright, branch-shaped blue as MARKED MEANING IS MARKED FORM.

Finally, the iconic rule SEMANTIC RELEVANCE IS CLOSENESS is also applied in this painting. The areas with (complete) human characters, specifically, are placed in the same line, rather than arranged randomly amid the picture (Fig. 4.4).

Thus, their similar meaning aligns with their closer placement.

The total number of applied GMs in this painting adds up to10 (Table 4.1), a high applicability of GMs in all 11 grammatical iconicity aspects (cf. Table 3.1). This is a common iconic extent across the figurative samples, with the average

applicability being 9.13. The analysis results of all 30 figurative paintings could be found in Appendix2.

Figure 4.1

The lugubrious game (Dali, 1929)

Figure 4.2 SALIENT zone

Figure 4.3 MARKED zone

Figure 4.4

SEMANTIC RELECVANCE

Visual elements Textual meaning Iconic alignment

Similarity Shape Similarity +

Difference Shape Difference +

Closeness Distance Semantic relevance +

Saliency

Size

Importance

+

Color + 4

Tone +

Sharpness +

Markedness

Size

Markedness

-

Color + 3

Tone +

Sharpness +

Total 10

Table 4.1 Grammatical iconicity for The lugubrious game

4.2 Grammatical iconicity in semi-figurative paintings

In the Semi-figurative group, Miro’s paintings are always composed of figure zones that are large or more in quantity, with visual contrasts of sharpness, tones or color saturation. It is therefore the case that the Semi-figurative paintings sampled are bountiful in iconic GMs.

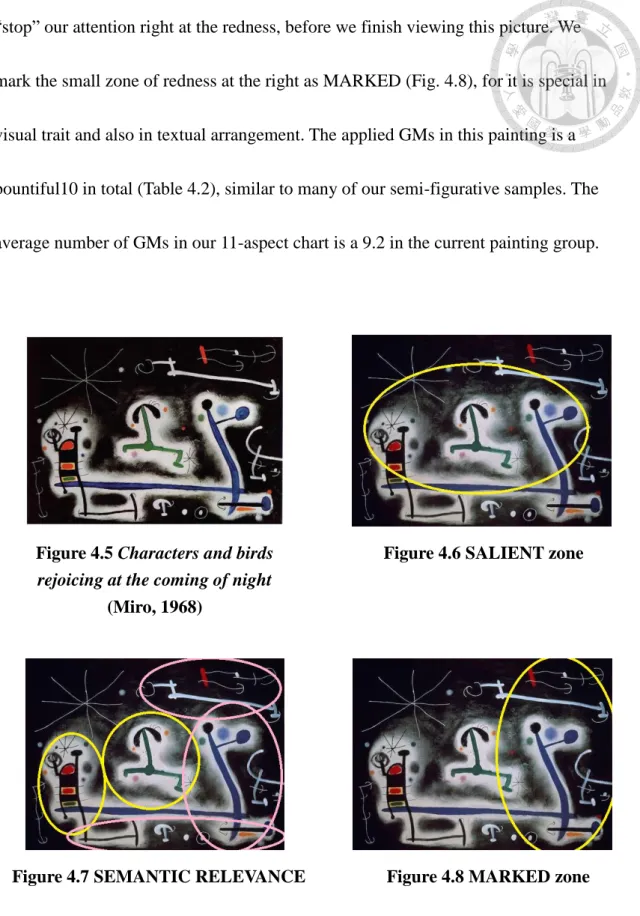

Below is a canonical case: In Characters and birds rejoicing at the coming of night (Fig. 4.5), the figure zones stand out, as hinted by both the title and the contrast

created by the dark “ground”. Moreover, the figure zones are greater in size and featured with more details, which intensify the visual complexity or sharpness of

these zones, aiding their textual importance (hinted by the title) in the whole

multimodal text. This fulfillment of SALIENT CONENT IS SALIENT FORM could be easily found throughout all of Miro’s sampled paintings (Fig. 4.6).

The characters again are arranged closely, following the iconic rule SEMANTIC RELEVANCE IS CLOSENESS (Fig. 4.7). The characters are portrayed in a

semi-figurative fashion, but still they display a similarity, so that the elements

representing “humans” are distinguished from his usual sign-like depictions of “stars”

and “birds” (cf. Corbella, 1993). This follows the principle SIMILARITY IN FORM IS SIMILARITY OF MEANING and DIFFERENCE IN FORM IS DIFFERENCE OF MEANING.

Finally, it is reasonable that the SALIENT zones display the brightest color saturation (red with black stripes for the left character, lush green figure in the middle, and the blue at the right). They are also circled by a layer of misty white, which further strengthens the tonal contrast. It is noticeable, however, that the abstracted line-like signs, which are deciphered as the “bird” element in Miro’s art language (Corbella,1993), all point to the right. Moreover, the dynamics of the lines is

accompanied by a specific spot of bright red at the lower-right corner of this picture.

It is a rather unusual combination, given that the same redness is featured at the SALIENT zones, but now reprised at the vectoring end of the lines, as if intended to

“stop” our attention right at the redness, before we finish viewing this picture. We

mark the small zone of redness at the right as MARKED (Fig. 4.8), for it is special in visual trait and also in textual arrangement. The applied GMs in this painting is a bountiful10 in total (Table 4.2), similar to many of our semi-figurative samples. The average number of GMs in our 11-aspect chart is a 9.2 in the current painting group.

Figure 4.5 Characters and birds rejoicing at the coming of night

(Miro, 1968)

Figure 4.6 SALIENT zone

Figure 4.7 SEMANTIC RELEVANCE Figure 4.8 MARKED zone