Incidence and relative risk

for developing cancer among patients with COPD: a nationwide cohort

study in Taiwan

Chung-Han Ho,1,2,3Yi-Chen Chen,1Jhi-Joung Wang,1Kuang-Ming Liao4

To cite: Ho C-H, Chen Y-C, Wang J-J,et al. Incidence and relative risk

for developing cancer among patients with COPD: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan.BMJ Open 2017;7:

e013195. doi:10.1136/

bmjopen-2016-013195

▸ Prepublication history for this paper is available online.

To view these files please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmjopen-2016-013195).

Received 9 July 2016 Revised 21 December 2016 Accepted 20 February 2017

For numbered affiliations see end of article.

Correspondence to Dr Kuang-Ming Liao;

abc8870@yahoo.com.tw

ABSTRACT

Objectives:This observational study aimed to examine the incidence of malignant diseases, including specific cancer types, after the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Taiwanese patients.

Setting:Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database.

Participants:The definition of a patient with COPD was a patient with a discharge diagnosis of COPD or at least 3 ambulatory visits for COPD. The index date was the date of the first COPD diagnosis. Patients with a history of malignancy disorders before the index date were excluded. After matching age and gender, 13 289 patients with COPD and 26 578 control participants without COPD were retrieved and analysed. They were followed from the index date to malignancy diagnosis, death or the end of study follow-up (31 December 2011), whichever came first.

Primary outcome measures:Patients were diagnosed with cancer (n=1681, 4.2%; 973 (7.3%) for patients with COPD and 728 (2.7%) for patients without COPD). The risk of 7 major cancer types, including lung, liver, colorectal, breast, prostate, stomach and oesophagus, between patients with COPD and patients without COPD was also estimated.

Results:The mean age of all study participants was 57.9±13.5 years. The average length of follow-up to cancer incidence was 3.9 years for patients with COPD and 5.0 years for patients without COPD ( p<0.01).

Patients with COPD were diagnosed with cancer (n=973, 73%) at a significantly higher rate than patients without COPD (n=708, 2.7%; p<0.01). The HR for developing cancer in patients with COPD was 2.8 (95%

CI 2.6 to 3.1) compared with patients without COPD after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities. The most common cancers in patients with COPD include lung, liver, colorectal, breast, prostate and stomach cancers.

Conclusions:The risk of developing cancer is higher in patients with COPD compared with patients without COPD.

Cancer screening is warranted in patients with COPD.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible, and the disease is

usually progressive and associated with lung inflammatory responses to noxious particles or gases.1 COPD was the sixth most common cause of death worldwide in 1990, and it was predicted to become the third most common cause by 2020.2Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of COPD, and smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer. Lung cancer risk increases with decreasing lung function in patients with COPD.3 The systemic effects of smoking and chronic systemic inflammation responses in patients with COPD contribute to the development of respiratory symptoms, functional impairment, and chronic comorbidities and include extrapulmonary cancers.4 A previous study demonstrated that COPD was associated with an increased risk of lung cancer mortality and extrapulmonary

Strengths and limitations of this study

▪ We analysed the risk of different cancer types in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and stratified them by disease severity according to the number of prescription drugs.

▪ The patients with COPD in our study were treated with COPD medications and were over 40 years old. Our study groups were matched by age and gender, and the data were analysed using the Cox model, including patient comorbidities. Our method differed from the standardised incidence ratio, which cannot adjust for comorbidities or medications.

▪ This study was a nationwide cohort study with a large number of participants, comprehensive enrolment of patients with COPD, and long-term follow-up.

▪ The limitations included lack of COPD severity information and cancer staging from the claims database.

▪ The data lacked consideration of other factors associated with COPD and cancer, such as life- style choices, physical activity and socio- economic status.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013195 on 9 March 2017. Downloaded from

cancer mortality.5In other cohort studies,4–8patients with COPD had increased mortality and risk of extrapulmonary cancers. However, previous studies have been limited by few participants or studying only populations at local hos- pitals and none of the other studies mention specific types of extrapulmonary cancers. The aim of this study was to use a nationwide cohort database to examine the inci- dence of malignant diseases, including specific cancer types, in Taiwanese patients after being diagnosed with COPD compared with Taiwanese patients without COPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Ethics statement

This study was conducted using an unidentifiable claims database provided by the National Health Insurance (NHI), and the principal investigator was requested to sign an agreement regarding compliance with the Computer-Processed Personal Data Protection Act during the proposal application. In addition, the policy of our Institutional Review Board (IRB) is consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Source of data

Taiwan launched a single-payer NHI programme in 1995. The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), a medical claims database, was established and released for research purposes. The NHIRD con- tains all inpatient and outpatient claims data in Taiwan, including patients’ demographic characteristics, dates of clinical visits, disease diagnoses, prescription medica- tions and expenditure amounts. More than 99% of the total population of Taiwan was enrolled in the NHI pro- gramme. In this study, we analysed the claim data of one million beneficiaries (from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2011) randomly sampled from all of the beneficiaries registered in 2000.

Study groups

In the present study, the definition of a patient with COPD was a patient with a discharge diagnosis of COPD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 490–492, 496) or at least three ambulatory visits for COPD who was also prescribed COPD medications, including short-actingβ2 agonists (SABA), long-acting β2 agonists (LABA), theo- phylline, inhaled short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA), long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), combination inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA, methylxanthines (MTX) and anticholinergics (AC).

Included patients were those over 40 years of age who received a diagnosis of COPD between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010. The index date was the date of the first COPD diagnosis. Patients with a history of malignancy disorders (ICD-9-CM codes 140 to 208) before the index date were excluded. During the study period, more than one readmission event may have occurred for the same patient; only the data from the

first-time hospitalisation record for COPD were analysed to ensure the independence of observations. In total, 13 289 patients with COPD were retrieved and analysed.

The control participants were selected from the remaining patients without COPD and with no history of malignancy before the index date. Patients who were treated with any of the above COPD medications were also excluded. Considering that cancer was a rare event and a stratified analysis for seven cancer types was used in our study, patients with COPD were matched 1:2 for age and gender to the control participants without COPD. In total, 26 578 patients without COPD or malig- nancy were selected as controls. Case and control parti- cipants were followed from the index date to malignancy diagnosis, death or the end of study follow-up (31 December 2011), whichever camefirst.

Definition of malignancy cases

The Registry of Catastrophic Illness Database was used in cancer diagnosis. When a patient is diagnosed by a phys- ician as having a malignancy, under Ministry of Health and Welfare guidelines, the patient can submit related information and apply for a catastrophic illness certifi- cate. The application is formally reviewed by more than two physicians. Patients with in situ malignancies were excluded from this study because patients with in situ malignancies do not qualify for a catastrophic illness certificate.

Comorbidities and medication measures

Baseline comorbidities were assessed for 1 year before the index date. They included chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia, and were recognised by the ICD-9-CM codes used to define each condition. COPD medication use on the index date was recorded. We examined the use of oral steroids, SABA, LABA, theophylline, ICS, SAMA, LAMA, ICS/LABA, MTX and AC. For estimating the effect of the number of COPD medications, patients with COPD in our study were divided into three groups: only one type of COPD medication, two types of COPD medication and more than two types of COPD medication.

Statistical analysis

We described the demographic characteristics of the patients, including age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, comorbidities and COPD medications.

Continuous variables are presented as the means with SDs, and discrete variables are presented as counts and percentages. Theχ2test was used for comparing categor- ical variables, and the differences among continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test. The pro- portion of patients with cancer was plotted by Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank test for comparing the differences between patients with COPD and patients without COPD. The relative risk of cancer was estimated by Cox proportional regression analysis, which was adjusted for potential confounding variables, such as

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/

age, sex and comorbidities. The statistical significance was inferred at a two-sided p value of <0.05. All of the statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) System, V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted using Stata V.12 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

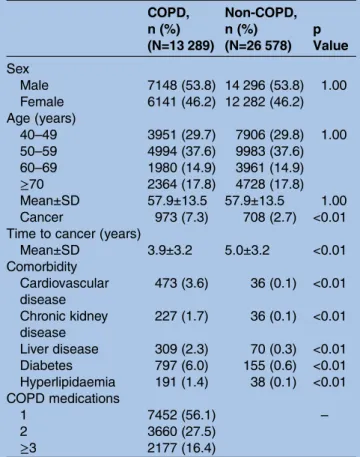

The characteristics and comorbidities of the study parti- cipants are shown in table 1. Overall, 13 289 patients with COPD enrolled in the study. The mean age±SD of the patients with COPD was 57.9±13.5 years. A 10-year age group distribution showed that 29.7% were 49 years of age or younger, 37.6% were 50–59 years, 14.9% were 60–69 years and 17.8% were 70 years of age or older.

The average length of follow-up was 3.9 years from COPD diagnosis to patients being diagnosed with any type of cancers compared with 5.0 years in the control groups ( p<0.01). Patients with COPD were diagnosed with cancer (n=973, 73%) at significantly higher rates than patients without COPD (n=708, 2.7%; p<0.01). The patients with COPD had a higher prevalence of comorbidities than the control group ( p<0.01), includ- ing cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes and dyslipidaemia.

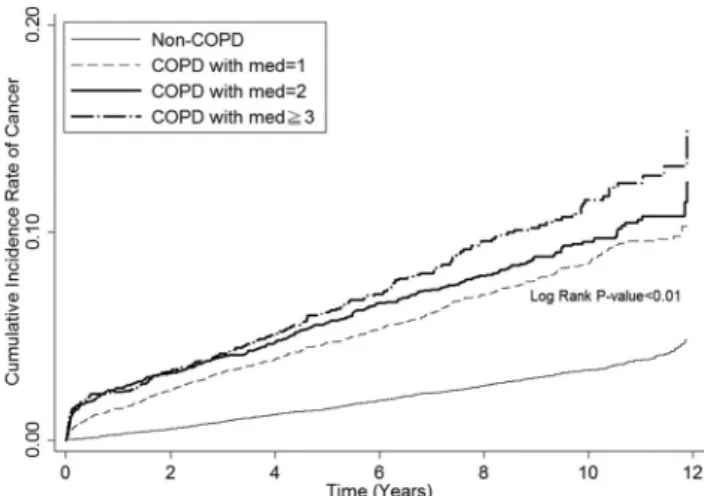

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence rate of any type of cancer in patients with or without COPD from the index date until the first occurrence of the cancer using Kaplan-Meier methods. The patients with COPD had higher cancer incidence rates compared with patients without COPD (log-rank test: p<0.01). Table 2 shows that the adjusted HR (AHR) of developing cancer among patients with COPD was 2.8 (95% CI 2.6 to 3.1) compared with patients without COPD after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities. For comparing the risk of cancer among each of the seven cancer types between patients with COPD and without COPD, the AHRs for each cancer type are reported in figure 2. Patients with COPD had significantly higher risks of lung (AHR 11.6; 95% CI 6.2 to 21.9), liver (AHR 5.0;

95% CI 2.4 to 10.4), colorectal (AHR 3.0; 95% CI 1.7 to 5.2), prostate (AHR 4.9; 95% CI 1.8 to 13.5) and oesophageal (AHR 6.0; 95% CI 1.1 to 32.7) cancer.

Moreover, the stratified analysis of the cancer risk between patients with COPD and without COPD by age group and sex for any type of cancer and each of the seven cancer types is also presented (figure 2).

Patients with COPD were divided into three groups according to the number of medications used to treat COPD, and figure 3 shows the cumulative incidence rates of any type of cancer in patients with or without COPD. Patients had a higher risk of developing cancer when more bronchodilator medications were used.

Table 3shows the AHR of developing cancer in patients with COPD who were taking multiple COPD medications compared with patients without COPD or patients with COPD who were treated with only one COPD medication after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities. Patients with COPD who were treated with COPD medications had a 2.6-fold (95% CI 2.3 to 3.0), 3.0-fold (95% CI 2.6 to 3.4) and 3.3-fold (95% CI 2.8 to 3.9) risk of any type of cancer for one, two and more than two medication treatments, respectively, compared with patients without COPD. The AHR of developing cancer among patients with COPD

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier plot for cancer incidence between patients with COPD and patients without COPD. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients with/without COPD

COPD, n (%) (N=13 289)

Non-COPD, n (%) (N=26 578)

p Value Sex

Male 7148 (53.8) 14 296 (53.8) 1.00

Female 6141 (46.2) 12 282 (46.2) Age (years)

40–49 3951 (29.7) 7906 (29.8) 1.00

50–59 4994 (37.6) 9983 (37.6)

60–69 1980 (14.9) 3961 (14.9)

≥70 2364 (17.8) 4728 (17.8)

Mean±SD 57.9±13.5 57.9±13.5 1.00

Cancer 973 (7.3) 708 (2.7) <0.01

Time to cancer (years)

Mean±SD 3.9±3.2 5.0±3.2 <0.01

Comorbidity Cardiovascular disease

473 (3.6) 36 (0.1) <0.01

Chronic kidney disease

227 (1.7) 36 (0.1) <0.01

Liver disease 309 (2.3) 70 (0.3) <0.01

Diabetes 797 (6.0) 155 (0.6) <0.01

Hyperlipidaemia 191 (1.4) 38 (0.1) <0.01 COPD medications

1 7452 (56.1) –

2 3660 (27.5)

≥3 2177 (16.4)

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013195 on 9 March 2017. Downloaded from

who used more than two types of COPD medication was 1.2 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.5) compared with patients with COPD who only used one type of medication. In addition, the AHR of developing cancer was 1.6 (95% CI 1.4 to 1.8) in male patients with COPD compared with female patients with COPD after adjusting for age and comorbid- ities. Being elderly was associated with a higher risk of developing cancer (50–59, AHR 1.8 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.2);

60–69, AHR 2.5 (95% CI 2.1 to 3.1); >70, AHR 2.2 (95%

CI 1.8 to 2.7)). Liver disease and diabetes were associated with a higher risk of developing cancer after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities (liver disease, AHR 2.3 (95%

CI 1.7 to 3.1); diabetes, AHR 1.3 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.7)).

DISCUSSION

Cancer type in patients with COPD

This is thefirst study to show the common types of cancer among patients with COPD. The five most common cancers after COPD diagnosis include lung cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer and oesophageal cancer in male patients and lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, liver cancer and stomach cancer in female patients. Patients with COPD had a higher risk of developing cancer and developed cancer within a shorter period of time compared with the patients without COPD.

Patients with COPD had a high prevalence of comorbid- ities compared with the patients without COPD, including chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes and dyslipi- daemia. Patients with COPD had an elevated risk of devel- oping cancer when they used more types of COPD medications compared with the patients without COPD.

In patients with COPD, the risk of developing cancer was significant when they used more than two types of COPD

medications compared with patients with COPD who only used one type of COPD medication.

Lung cancer and COPD

Both COPD and lung cancer have high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide.9 10 Previous studies11 12 have shown that patients with COPD are at increased risk for the development of lung cancer, and lung cancer is an important cause of death in patients with COPD.13 Patients with COPD are at increased risk for lung cancer because most of them have a history of smoking.

Additionally, patients with COPD are of lower socio- economic status compared with the general population, and socioeconomic status may affect quality of life, including environmental exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution; these factors may influence the development of lung cancer.

Chronic inflammation after extracellular stimulation, such as tobacco smoking and occupational and environ- mental inhalants, play a key role in COPD and lung cancer. Thus, shared risk factors and inflammatory path- ways lead to the similar pathological mechanisms of COPD and lung cancer.14

Liver cancer and COPD

The α1-antitrypsin deficiency is one of the most common inherited disorders among white persons and predisposes individuals to COPD, cirrhosis and hepato- mas.15 16 Theα1-antitrypsin deficiency is not an import- ant cause of childhood liver diseases in Southeast Asian populations17 and is also rare in Taiwan. Liver cancer is one of the most common tumour types in Taiwan because Taiwan has a high prevalence of virus hepatitis, Table 2 HR of developing cancer in relation to baseline characteristics of the study participants

Crude HR

(95% CI) p Value

AHR*

(95% CI) p Value

Patients

COPD 2.9 (2.7 to 3.2) <0.01 2.8 (2.6 to 3.1) <0.01

Non-COPD 1.0 (ref) 1.0 (ref.)

Sex

Male 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) <0.01 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) <0.01

Female 1.0 (ref) 1.0 (ref)

Age (years)

40–49 1.0 (ref) 1.0 (ref)

50–59 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) <0.01 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) <0.01

60–69 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) <0.01 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) <0.01

>70 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) <0.01 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) <0.01

Comorbidity

Cardiovascular disease 1.8 (1.2 to 2.5) <0.01 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) 0.31

Chronic kidney disease 2.2 (1.4 to 3.4) <0.01 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) 0.84

Liver disease 4.1 (3.1 to 5.3) <0.01 2.3 (1.8 to 3.1) <0.01

Diabetes 2.7 (2.2 to 3.4) <0.01 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) <0.01

Hyperlipidaemia 2.4 (1.6 to 3.9) <0.01 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) 0.69

*AHR is based on Cox proportional hazard regression model with adjustment for age, sex and comorbidities.

AHR, adjusted HR; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/

with ∼20% of the general population suffering from chronic hepatitis B virus infection and 4.4% of the population from chronic hepatitis C virus infection.18

Colorectal cancer and COPD

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers in patients with COPD.19 Patients with COPD experienced sensations of dyspnoea in their daily activities, and

consequently tended to lead more sedentary lifestyles;

sedentary behaviour may also increase the risk of colo- rectal cancer. A nationwide population-based observa- tional study investigated the influence of COPD on intensive care unit admissions, medication treatments and mortality following colorectal cancer surgery.20 The authors identified 7.9% of colorectal cancer surgery patients as having a COPD diagnosis, and in this Figure 2 The overall and stratified analyses for the incidence and HR of developing cancer between patients with COPD and patients without COPD among any type of cancer and the seven major cancer types. AHR, adjusted HR; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013195 on 9 March 2017. Downloaded from

population, more complications were noted after surgery, including higher ICU admission rates, more fre- quent need for mechanical ventilation, higher rates of requiring reoperation and more frequent inotropes/

vasopressors. The 30-day mortality after surgery was 13.0% in patients with colorectal cancer and COPD and 5.3% in patients with colorectal cancer without COPD.

A study21 demonstrated that COPD is one of the most common comorbid conditions in patients with colon cancer. The receipt of adjuvant therapy was related to COPD (55.2% vs 61.5% of patients with vs without COPD, respectively; OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99), but

patients with COPD and colon cancer had survival bene- fits after receipt of adjuvant therapy. Although COPD appeared to be a barrier to chemotherapy, chemother- apy can provide a survival benefit to patients who have colon cancer with COPD. Many colorectal cancers can be prevented through regular screening, and screening is also crucial in patients with COPD.

Prostate cancer and COPD

Dysfunction in the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, such as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, has been noted in patients with COPD.22 23 The correlation between serum levels of testosterone and risk of prostate cancer is still controversial.24 25 One recent study found that patients with COPD had a significant reduction in total and free testosterone levels compared with con- trols.26 The relationship between testosterone level and prostate cancer in patients with COPD needs further investigation. In our study, more than 80% of prostate cancers were diagnosed in men who were 60 years of age or older. A prostate-specific antigen-based screening test for prostate cancer may be warranted in the elderly male population with COPD.

Aerodigestive cancer and COPD

It is widely accepted that smoking is a risk factor for oro- pharyngeal cancer, oesophageal cancer and COPD. In our study, development of cancers of the upper aerodi- gestive tract, including oropharyngeal and oesophageal cancers, were also common in patients with COPD. A cohort study among 17 774 men showed a positive Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier plot of cumulative incidence rates of

cancer among patients with COPD with different medications and patients without COPD. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3 HR of developing cancer in relation to baseline characteristics and COPD medications of the study participants AHR of cancer among all study

participants (95% CI)

p Value

AHR* of cancer for patients with COPD alone (95% CI)

p Value Patients

Non-COPD 1.0 (ref) –

COPD with only 1 medication 2.6 (2.3 to 3.0) <0.01 1.0 (ref)

COPD with 2 medication 3.0 (2.6 to 3.4) <0.01 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) 0.16

COPD with≥3 medication 3.3 (2.8 to 3.9) <0.01 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) 0.02

Sex

Male 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) <0.01 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) <0.01

Female 1.0 (ref) 1.0 (ref)

Age (years)

40–49 1.0 (ref) 1.0 (ref)

50–59 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) <0.01 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) <0.01

60–69 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) <0.01 2.5 (2.1 to 3.1) <0.01

>70 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) <0.01 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) <0.01

Comorbidity

Cardiovascular disease 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) 0.27 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) 0.15

Chronic kidney disease 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) 0.82 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) 0.76

Liver disease 2.3 (1.8 to 3.1) <0.01 2.3 (1.7 to 3.1) <0.01

Diabetes 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) <0.01 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) 0.02

Hyperlipidaemia 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) 0.68 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) 0.66

*AHR is based on Cox proportional hazard regression model with adjustments for age, sex and comorbidities.

AHR, adjusted HR; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/

association between smoking and subsequent cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract (relative risk, 2.02; 95% CI 1.01 to 4.06) with evidence of dose–response effects.

Regular smoking will increase the risk of COPD and aerodigestive tract and lung cancers.27In addition to the same risk factor of smoking, the higher risk of aerodiges- tive cancers in patients with COPD can be partially explained by socioeconomic status. A previous study showed that the risk of aerodigestive cancers cannot be entirely explained by smoking, alcohol consumption and diet. Socioeconomic status was also a risk factor for upper aerodigestive tract cancers.28There is growing rec- ognition of the importance of systematic examination of the oral cavity, oropharynx and neck, which can detect precancers and cancers at an early and curable stage in patients with COPD with a history of smoking.

Cancer types in patients with COPD

Our study showed a positive association between COPD and the subsequent development of cancer. The AHR of developing cancer in patients with COPD was 2.8 (95%

CI 2.6 to 3.1) compared with patients without COPD after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities. In a previ- ous study of the incidence of cancer, smoking increased the risk of cancer of the oropharynx, upper aerodiges- tive tract and lung.27 From our analysis, in addition to the cancers aforementioned, common cancer types diag- nosed with high frequency in patients with COPD included liver, colon and breast cancers.

A population-based study29 revealed that 12% of all patients with cancer had COPD at the time of cancer diagnosis, with ∼15% of those patients over the age of 65. In addition to lung cancer, there was no difference in the stage at diagnosis between patients with cancer with or without COPD. After using a multivariate Cox regression model, the survival rate was poor in patients with COPD, especially for elderly patients with colon, rectum, larynx, prostate or urinary bladder cancer.

Another study conducted in Taiwan also used the NHIRD, but the researchers presented the risk of cancer in COPD using a standardised incidence ratio. From 1995 to 2008, they enrolled 50 875 patients with COPD over 20 years of age and found that head and neck, oesophageal, lung and mediastinal, breast, and prostate cancer were higher in patients with COPD compared with the general population. In our study, we further analysed the prescription pattern, including bronchodi- lators and steroid, in all patients with COPD from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2011 with stricter inclu- sion criteria which aged more than 40 years and visit at least three ambulatory visits for COPD. In our study, we analysed the comorbidities in patients with and without COPD and HR of developing cancer in relation to base- line characteristics which was not performed in Chiang and colleagues’ study. We also found that the more bronchodilators patients with COPD used, the more risk of developing cancer. If patients with COPD used more than two bronchodilators representing COPD severity,

the disease severity of COPD may be associated with increasing cancer risk.

In summary, in Chiang’s study, they included patients aged more than 20 years. We enrolled patients aged more than 40 years. Patients with COPD in our study were treated with COPD medications and non-COPD groups did not get treated with any COPD medications.

In Chiang’s study, they did not survey the COPD medica- tions. Our study exactly matches by age and gender with the Cox model and analysed the comorbidities. In Chiang’s study, they used SIR to analyse the risk of cancer. SIR cannot adjust comorbidity and medications.

In figure 2, consistent with the results of Chiang’s studies, patients with COPD had a higher risk of lung, aerodigestive and prostate cancer. There was difference in association between COPD and cancers in our study compared with Chiang’s study after adjusting for age and gender. In our study, patients with COPD had a higher risk of liver and colorectal cancer compared with patients without COPD. Although the risk of head and neck cancer was higher in patients with COPD com- pared with general population in Chiang’s study, there was no significant difference in risk in our study after adjusting for age and gender. In addition to lung and aerodigestive cancer, we suggest that patients with COPD follow-up cancer screening may include liver and colo- rectal cancer.

Kornum et al30 used the Danish National Registry of Patients and their nationwide cancer registry databases to show the incidence of various cancers in 236 494 patients with COPD from 1980 to 2008. They included patients aged 40 years or older with COPD. Patients were enrolled after afirst-time hospitalisation, outpatient clinic visit or a visit to an emergency department with a diagnosis of COPD from ICD-8 or ICD-10 codes. The researchers focused on tobacco-related and alcohol- related cancers, but they did not evaluate comorbidities and medications in patients with COPD. They found that lung, aerodigestive and liver cancers were increased in patients with COPD.

Limitations

One major limitation was that some of the data, includ- ing histories of cigarette smoking, pulmonary function, degree of dyspnoea, COPD severity and cancer staging, were not available from the claims database. We used the database to demonstrate that COPD was significantly associated with a high risk of cancer, regardless of COPD severity. As a representation of COPD severity, we also divided the COPD population into three groups according to the number of medications they used to treat COPD. After the stratification, we found that patients who used more COPD medications were at a higher risk of developing cancer. Other limitations should be acknowledged, including that the data were based on insurance records that lacked consideration of other factors associated with COPD and cancer, such as lifestyle choices, physical activity and socioeconomic

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013195 on 9 March 2017. Downloaded from

status, which may have led to possible errors. The limita- tions of the analysis based on the database include an inability to truly characterise the patients and controls.

The study was a nationwide cohort study; we believe that the large number of participants, the comprehen- sive enrolment of patients with COPD and the long-term follow-up ensured that the data are normally distributed and that the results are significant.

CONCLUSION

In addition to lung cancer, patients with COPD have a higher risk of developing other types of cancer, and phy- sicians should closely monitor and follow-up with these patients.

Author affiliations

1Department of Medical Research, Chi Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan

2Department of Pharmacy, Chia Nan University of Pharmacy and Science, Tainan, Taiwan

3Department of Hospital and Health Care Administration, Chia Nan University of Pharmacy and Science, Tainan, Taiwan

4Department of Internal Medicine, Chi Mei Medical Center, Chiali, Taiwan

Contributors C-HH was involved in acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; Y-CC was involved in acquisition and analysis of data;

J-JW contributed to conception and design; K-ML was involved in drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Chi Mei Medical Center (IRB no. 10405-E03).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional data are available.

Open Access This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

REFERENCES

1. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: gold executive summary.Am J Respir Crit Care Med2013;187:347–65.

2. Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections.Eur Respir J 2006;27:397–412.

3. Wasswa-Kintu S, Gan WQ, Man SF, et al. Relationship between reduced forced expiratory volume in one second and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Thorax

2005;60:570–5.

4. Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghé B, et al. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD.Eur Respir J2008;31:204–12.

5. van Gestel YR, Hoeks SE, Sin DD, et al. COPD and cancer mortality: the influence of statins.Thorax2009;64:963–7.

6. Purdue MP, Gold L, Järvholm B, et al. Impaired lung function and lung cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish construction workers.

Thorax2007;62:51–6.

7. Tkác J, Man SF, Sin DD. Systemic consequences of COPD.Ther Adv Respir Dis2007;1:47–59.

8. Nakayama M, Satoh H, Sekizawa K. Risk of cancers in COPD patients.Chest2003;123:1775–6.

9. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010.CA Cancer J Clin2010;60:277–300.

10. Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey.Am J Respir Crit Care Med2007;176:753–60.

11. Skillrud DM, Offord KP, Miller RD. Higher risk of lung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A prospective, matched, controlled study. Ann Intern Med 1986;105:503–7.

12. Tockman MS, Anthonisen NR, Wright EC, et al. Airways obstruction and the risk for lung cancer.Ann Intern Med1987;106:512–18.

13. Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, et al. Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (ECLIPSE).

Eur Respir J2008;31:869–73.

14. Lee G, Walser TC, Dubinett SM. Chronic inflammation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer.Curr Opin Pulm Med2009;15:303–7.

15. Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. A review ofα1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med2012;185:246–59.

16. Stoller JK, Brantly M. The challenge of detecting alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.COPD2013;10(Suppl 1):26–34.

17. Lee WS, Yap SF, Looi LM. alpha1-Antitrypsin deficiency is not an important cause of childhood liver diseases in a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population.J Paediatr Child Health2007;43:636–9.

18. Chen CH, Yang PM, Huang GT, et al. Estimation of seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in Taiwan from a large-scale survey of free hepatitis screening participants.J Formos Med Assoc 2007;106:148–55.

19. Chiang CL, Hu YW, Wu CH, et al. Spectrum of cancer risk among Taiwanese with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Int J Clin Oncol2016;21:1014–20.

20. Platon AM, Erichsen R, Christiansen CF, et al. The impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on intensive care unit admission and 30-day mortality in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a Danish population-based cohort study.BMJ Open Respir Res 2014;1:e000036.

21. Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Guo Z, et al. The impact of chronic illnesses on the use and effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer.Cancer2007;109:2410–19.

22. Casaburi R, Bhasin S, Cosentino L, et al. Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Am J Respir Crit Care Med2004;170:870–8.

23. Semple PD, Beastall GH, Watson WS, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction in respiratory hypoxia.Thorax1981;36:605–9.

24. Wu AH, Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, et al. Serum androgens and sex hormone-binding globulins in relation to lifestyle factors in older African-American, white, and Asian men in the United States and Canada. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1995;4:735–41.

25. Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, et al., Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies.J Natl Cancer Inst2008;100:170–83.

26. Karakou E, Glynos C, Samara KD, et al. Profile of endocrinological derangements affecting PSA values in patients with COPD. In Vivo 2013;27:641–9.

27. Iribarren C, Tekawa IS, Sidney S, et al. Effect of cigar smoking on the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer in men.N Engl J Med1999;340:1773–80.

28. Al-Dakkak I, Khadra M. Socio-economic status and upper aerodigestive tract cancer.Evid Based Dent2011;12:87–8.

29. van de Schans SA, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Biesma B, et al. COPD in cancer patients: higher prevalence in the elderly, a different treatment strategy in case of primary tumours above the diaphragm, and a worse overall survival in the elderly patient.Eur J Cancer 2007;43:2194–202.

30. Kornum JB, Sværke C, Thomsen RW, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study.Respir Med2012;106:845–52.

on 9 December 2018 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://bmjopen.bmj.com/