CHAPTER THREE

METHODOLOGY

In this chapter, the design of the experiment, which includes two phases, is explained. The first phase provides a brief introduction of a pilot study. The second phase is a full description of the main study that contains six parts: description of the participants, the method of selecting and designing instruments, procedures of instruction, data collection, scoring and the methods of analyzing the data.

Pilot Study

The pilot study is explained in two parts. The first part is to see whether the modified test materials were appropriate for the participants. The second part was to see whether the time spent on treatment was suitable. For the first part, a class of 31 ninth graders read two passages for ten minutes and wrote down how they felt about the materials. The two passages were retrieved from the Internet and adapted for this study. The length and difficulty level were well-controlled between the two passages. The amount of words in the passages was about 240. The difficulty level was 3.4 according to Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Index in computer software. The sentence structure was within the scope of common use patterns for junior high school students. A detailed description of the test materials was given in Selecting Test Materials section (p.37-39 in this thesis). Based on their feedback, the researcher found no student mentioned they read the stories before the pilot study. Unfamiliar materials are suitable for comprehension assessment, for students need to read to understand the text (Wolf, 1993). About ten students expressed they could understand the stories. Another ten said that they could figure out the main ideas of the stories. The other eleven claimed they had difficulty understanding the whole

text. Among the eleven students, four said they understood nothing. According to these reports, the researcher found the responses echoed the current situation in a junior high English class. Students of mixed-ability English were arranged in one class. They perceived the texts differently, but a great proportion of students generally understood the text. Therefore, the two passages were used as the test materials in the main study.

The second phase was to see whether the teaching procedure went smoothly and to test whether the time spent on treatment was suitable, and whether students liked QtA lessons. A class of 37 ninth graders participated in this phase of pilot study in December, 2004 for ninety minutes (two-class periods). In the first five minutes the researcher introduced the QtA strategy (Beck et al., 1997): the teacher and students need to construct meaning collaboratively through discussion. In the following seventy minutes, two passages, one passage for each period, taken from Aesop’s Fables published by Caves Books (Olivier, 1999) used as treatment materials,

one with 371 words and the other with 463 words, were read and discussed using QtA techniques. The first passage with 4 Initiating Queries took thirty minutes to complete. The second passage containing 5 Initiating Queries took another forty minutes. During the process, the researcher read one segment until the stopping point. She stopped and began asking Initiating Queries like “What has the author told us about … ?” or “What does the author mean by that?” Students responded.

With the responses, the researcher asked Follow-up Queries like “What do you think about someone’s comment?” or “What did the author say to make someone think of that?” The procedure proceeded till the end of the passage. The last fifteen minutes was for students to do 10 multiple-choice questions (five for each passage) and then wrote freely to show their perception about the lesson. The pilot study was video-taped and the transcription was taken as a sample of the QtA procedure.

After the pilot study, the researcher made the some adjustments based on classroom observation and students’ reports. First, it was decided to use shorter text and more queries for discussion. Only one passage arranging from 500 to 650 words in each QtA lesson (90 minutes) would be used and the Initiating Queries in each lesson were increased to ten Initiating Queries to enhance the quality of discussion.

In addition, since some students went astray easily, more use of discussion moves like

“Turning back to text” (Beck et al., 1997, p. 82) and “Modeling” would be used (Beck et al., 1997, p. 86) to keep the focus of the text.

Main Study

With the feedback from the pilot study, the researcher modified the material and treatment for the main study.

Participants

Two classes of ninth graders (70 students) in a junior high in Taipei City participated in the experiment. One class with thirty-six students was the experimental group. The other class with thirty-four students was the control group.

However, after data collection, several students were excluded because of invalid data.

Four of the students in the experimental group did not produce anything in the pretest.

They left the answer sheet blank or drew pictures on them. They wrote nothing in both the written recall and comprehension questions. Three of the students in the control group were excluded for the same reason. Furthermore, in the posttest one student in the experimental group slept on the desk as soon as he entered the classroom. The teacher tried to wake him up, but he did not move. His test performance was, therefore, invalid. Altogether, five in the experimental group and three in the control group were ruled out. The number of participants was sixty-two,

with 31 in each group.

The participants had learned English for at least three and a half years. They began learning English formally since they were in the sixth grade in the year of 2000 when the policy had it that students in the fifth grade and in the sixth grade started to learn English for two periods per week at school in the same year.

In the seventh grade in junior high, students had three periods per week. They had four regular periods and one optional remedial period in the eighth grade. And in the ninth grade, students had five English periods per week, including four regular classes and one must-take optional remedial class after four o’clock (the eighth period). The researcher was the English teacher of both groups when they were in the ninth grade.

Materials Selection

The selection of materials could be described in three phases. The first phase was on deciding which type of the text to be used. The second phase was about the selection of stories for the pretest and the posttest. The third phase was about the selection of stories for treatment sessions.

Determining Type of Text

According to Beck et al. (1997), Questioning the Author technique can be used either in expository texts or narrative ones. Narrative texts then were chosen in this study for several reasons. First of all, narratives not only provide readers with new information but also ignite pleasant experiences. People of all ages love to read stories or listen to stories. People are easy to identify themselves with stories that interest them, so they can make their own judgment and have their own interpretation.

Among the stories, Aesop’s Fables is an all-time favorite (Fry, Kress & Fountoukidis,

2000), so fable was chosen as the main genre in the study.

Second, narration might be a more familiar genre for junior high students and would help generate more interpretation. With vivid character development and appealing plot, students could easily follow the story pattern and think critically (McDaniel, 2004).

Thirdly, Beck et al. (1997) used the fable “The Fox and the Crow” as a narrative example for planning queries. As the researcher was applying Questioning the Author as a model for treatment in the pilot study and the main study in English classes, the same genre of material was used for the purpose of replication.

Last but not least, students may be familiar with some fable stories. Although they know the fables in Chinese, they never read them in English. Using fable stories can balance between students’ schema and the difficulty of the task so that all participants, regardless of proficiency, may engage in the training.

With these reasons, the fable stories instead of other genre of stories were singled out as the main type of pretest and posttest materials and treatment materials.

Selecting Test Materials

The second phase would be selection of stories for the pretest and the posttest.

Two Indian fables were selected from the website. These two passages were chosen to assess reading comprehension in terms of written recall, inference generation and three types of comprehension questions.

Two Indian fables were selected for two reasons. The genre fable is the same as the passages used for treatment. However, in order to assess students’

comprehension, the story content should be unfamiliar with students. Both of them were taken from the same website on the Internet. In addition, both passages shared some similarities. First, the main characters are a person from a royal family and an

animal. In the very beginning of the passage, the relationship or the encounter of the characters is described. The crisis which the characters have to deal with starts the second paragraph. The climax appears in almost the same place in the passages (the twenty-sixth clause in the Foolish Friend and the twenty-fifth clause in the Prince and the Lion). In other words, students would process almost the same amount of text to reach the climax part.

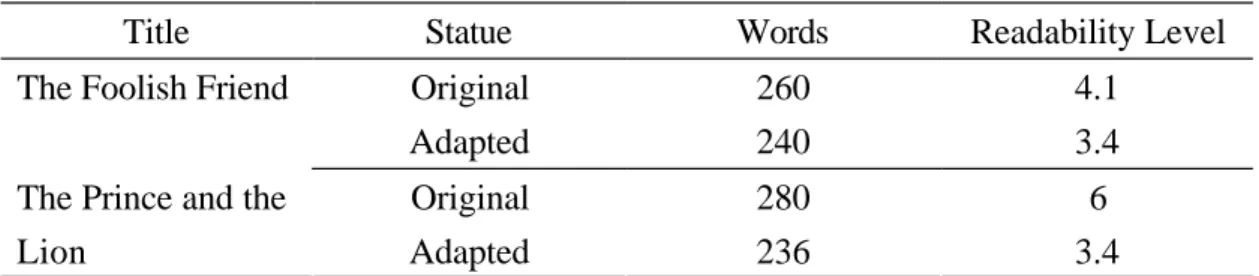

Table 4. Materials for the Pretest and the Posttest

Title Statue Words Readability Level

Original 260 4.1

The Foolish Friend

Adapted 240 3.4

Original 280 6

The Prince and the

Lion Adapted 236 3.4

As shown in Table 4, the first passage “the Foolish Friend” contained 260 words and the difficulty level was 4.1. The second passage “the Prince and the Lion” had 281 words and the difficulty level was 6, for there were many Indian names in the story. In order to minimize the discrepancies of both passages, the researcher decided to make a few adaptations on the materials. The adaptations were done based on two criteria. One was for length of the passages. The other is for difficulty level. As for length, the researcher first deleted the moral lesson given for children at the end of the passages because the moral lesson imposed on students’

interpretation. In addition, the names of the main characters and the kingdom, which were Indian names, were deleted or changed to a common English name for ease of reading. For example, in the first passage, the names in the sentences “there was a king called Gori Sing” and “the king Gore Sing fell asleep” were deleted. In the second passage, “there was a Kingdom named Awadha,” “The Kingdom was ruled by Maharaja Raghuvendra Sing,” and “He had a prince called Devendra Singh” were changed to “there was a Kingdom,” “the Kingdom was ruled by a king” and “He had

a prince called Mark.”

As far as difficulty level is concerned, the following adjustments were done to reach the same readability. First, words that are not in the 2000 word list issued by the Ministry of Education for the junior high graduates (2003) would be replaced with easier words or similar expressions that would not affect the meaning of the text.

For example, “struck” became “hit” and “Jungle” became “forest.”

What is more, sentence patterns that might cause difficulty were replaced with easier ones and a passage in just one long paragraph was divided into two paragraphs to ease students’ reading burden. For example, in the second passage, “it was his duty to help the lion,” the researcher changed into it “he should help the lion.” The modified final version of the pretest and posttest passages is shown in Appendix A.

With the adaptations the passages are of 240 and 236 words long and the difficulty level is the same, 3.4. Three experienced English teachers read the passages and agreed that they were comprehensible and suitable for ninth graders to read.

The passages were reduced to around 240 words because the readings in the two textbooks which are mostly narratives, are about 220-240 words in length. In terms of difficulty level, a passage with a 3.4 difficulty level is proper because it is lower than either the reading in the Book Five of Hess Temporary Edition (3.6-7.2) or in the Book Five in the Old Standard Edition (3.6-7.3). Thus, the length and the difficulty level of both passages were appropriate for ninth graders to comprehend independently of instruction.

The two passages were piloted with thirty-one students from one class of mixed-ability ninth graders. As mentioned in the pilot section, after they finished reading, based on their report of difficulties, the researcher found more than two-thirds students felt the length and difficult level were appropriate. Materials for pretest and posttest were, therefore, finalized (Appendix B).

Treatment Materials

Reading Passages. The third part was the selection of stories for treatment sessions. Aesop’s Fables of easy readers series by Caves Books (1999) was chosen.

Among the three levels of this series, the lowest one 1000-word level was chosen because the average junior high graduates are suggested to reach the basic 1000-word level (MOE, 2003). Among the thirty fable stories in this level, six were chosen because their lengths are between 500 and 650 words. The length is suitable for two-class periods and the content contains controversial points for discussion.

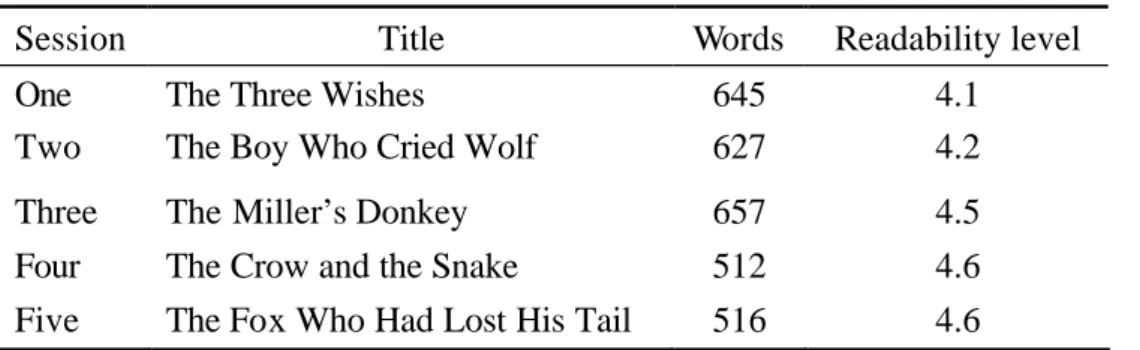

In the next stage of selection, one out of the six passages was ruled out because its readability, 2.6 is far below the rest five, which ranged between 4.1 and 4.6, based on Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Index in computer software. The range is within those of the readings in the textbooks (either Hess Temporary Edition or Old Standard Edition). Table 5 shows a list of treatment materials.

Table 5. Materials for Treatment

Session Title Words Readability level

One The Three Wishes 645 4.1

Two The Boy Who Cried Wolf 627 4.2

Three The Miller’s Donkey 657 4.5

Four The Crow and the Snake 512 4.6

Five The Fox Who Had Lost His Tail 516 4.6

Queries. Besides five treatment stories, queries and Comprehension Check

after the treatment are part of treatment materials.

The queries presented after each segment of the story were developed from a set of Initiating, Follow-up and Narrative queries for Questioning the Author (Beck et al., 1997) classrooms. Initiating Queries are the first query the teacher probes to elicit students’ response. For example, “What is the author trying to say?”

Follow-up Queries are queries that the teacher asks based on students’ response or interaction. Follow-up queries can mark the important part, bring back students’

attention and elaborate students’ response. They are “Why do you think so?” “Do you agree with what someone said?” Narratives Queries are like “How do things look for this character now?” They help students concern about characters and “the author’s crafting of the plot” (p. 42). The types of queries focus on main idea, character development or confusing parts of the story, so that they aid understanding of the reading and help readers construct their own meaning.

Comprehension Check. To motivate students follow the lesson and

participate in discussion, nine multiple-choice questions plus one open-ended question for each treatment passage are designed by the researcher. They are used to motivate students in engaging in the reading, but will not be used as data in the study. The first three questions are about facts of the story. The next three questions are about interpretation of the story. The last three questions are readers’ opinion, judgment on one of the characters (Sandora et al., 1999), and moral lesson of the story. The open-ended question “What can we learn from the story?” is used to evaluate the degree of interpretation after each treatment session. An example of Comprehension Check along with the sample reading will be described in a later section.

Instruments

To answer the research questions, the researcher adopted three instruments for data collection.

1. Two recall sheets for each of the passage for the pretest and the posttest (Appendix C).

2. Comprehension question sheets for the pretest and the posttest (Appendices D &

E).

3. A Perception Questionnaire (Appendices F & G).

Each instrument served different research purpose and will be further explained in detail.

Pretest and Posttest Written Recall Sheets

This study adopted written recall as a measurement of comprehension because recalls were “common measures in studies of te xt understanding” (p. 187, Sandora et al., 1999) and written recall may offer presentation of how readers process the passage (Bernhardt, 1991; Brantmeier, 2005), such as the storage and organization of the information, the strategies of choosing particular message and the way readers

“reconstruct the text” (Alderson, 2000, p. 230).

In this study, students are asked to write the recall in Chinese because recall done in L1 yielded better outcome (Lee, 1986) and L1 writing ability should be attended when interpreting the test result of L2 reading comprehension (Brisbois, 1992). Written recalls in L1 were, therefore, used as measurement in this study.

In the present study, the recall would be measured at two levels: matching or mismatching of original te xt. The matching part would be the recall and the mismatching part would mainly be two types of inferences: text-based inferences, reader-based inferences.

Three Types of Comprehension Questions for a Pretest and a Posttest

Three types of comprehension are designed for this study with an integration of some classifications (DuBravac & Dalle, 2002; Gray, 1960; Hill & Parry, 1994;

Pearson & Johnson, 1978). According to Gray (1960), students’ understanding of text, especially literature, can be observed from three aspects: whether they read the lines (literal), whether they read between the lines (interpretive), or whether they read

beyond the lines (evaluative or responsive). Each type contains three questions.

As reviewed in Chapter Two, the first type is factual question about facts, events, or causes of the story. The second one is interpretive question about the theme, character development or judgment of the event. They are equivalent to text-based inferences because readers need to generate their own interpretation automatically when they process the text. The third type is responsive question about students’

personal responses, evaluation of author’s intent and problem-solving. This type of question is similar to reader-based inferences, for readers need to resort to personal experiences and knowledge to generate inferences.

In sum, factual questions could reach the textbase and detect how much readers comprehend the explicit text; interpretive questions could create a situation model and elicit to what extent readers trace implicit text; responsive questions could connect the situation model with experiences and explore how readers interweave the implicit script into personal experiences and knowledge. With these types of questions, whether students comprehended the texts or to what degree students understood the texts could be detected (See Appendices D & E).

A Perception Questionnaire

A Perception Questionnaire was designed by the researcher to find out students’

perceptions toward QtA lessons (see Appendices F & G). The first two questions ask students to do the ranking among the four options to evaluate their own ability growth after treatment and the difficulty encountered during the treatment. The third question, consisting of three open-ended questions requires students to compare QtA lessons with traditional ones, to report the affect toward QtA lessons and to assess the feasibility of QtA in future practice.

Treatment Procedure

The experiment was done one period on Wednesdays and Thursdays for five

consecutive weeks in April and May, 2005. Each group received instruction of one passage for two periods each week. The following are the treatment procedure for each group.

Experimental Group (hereafter Group E)

In Group E, a passage is divided into ten segments for discussion, followed by a Comprehension Check. These activities are completed in two class periods on two consecutive days, that is, ninety minutes. In the first period on Wednesday, the reading of the story and the discussion were brought on until the sixth segment. On Thursday, the researcher would review the content of the first period and continue the rest of four segments. Then students had to answer the Comprehension Check for the treatment story.

All the stories were read aloud by the teacher. Students listened and read silently along in their own copies. It was decided that the researcher read aloud the story because some students had weak decoding skills and might not read aloud the passages smoothly. Reading aloud to students is a key activity in literature-based instruction and more teachers claimed they read aloud daily to their students recently (Morrow & Gambrell, 2000). Listening to the reading from the instructor also helped students recognize words more easily (Danks & End, 1987). The researcher might also control the reading speed of each story.

In the experimental group, the researcher used the Questioning the Author strategy to read the passage. Participants were seated in a big circle in the classroom so that they could see each other face to face. Every student was given a reading

handout and a query handout. The queries were not inserted and printed in the reading passage in order to keep the passage intact. In Beck et al.’s study (1997) and Sandora et al.’s study (1999), the queries were given orally by the teacher. In this study, the researcher decided to give students a note for fear that participants might not understand the queries in English in an EFL context.

In a typical lesson, the researcher first explained the queries of the day before she read the first segment so that students had ideas what these English queries are.

Then she read, stopped at where each segment ended, asked the query and led a whole-class discussion based on the planned queries, each for about six minutes.

Stopping points are selected based on the importance to the theme or whether the information is confusing (Beck et al., 1997; Sandora et al., 1999). Upon the end of the first segment discussion, the second segment would be read and queries followed.

The process continued in a cycle until the sixth segment for the first day. A few minutes were reserved for either more discussion or the summary part.

In the second period the next day, the researcher reviewed the content in the previous six segments and then explained the rest four queries first for ten minutes before reading the rest four segments. QtA lessons for the second day were given for twenty-four minutes. Four minutes was retained for more discussion. The last seven minutes was test time for participants to answer nine multiple-choice questions and one open-ended question.

A Sample Lesson. The reading passage of the day was “the Miller’s Donkey”

(Appendix H with all the treatment stories and queries). The Queries used in this sample lesson tried to lead students to think in particular directions. Some focused on theme, some on character, some on judgment of the story, and still others on response from participants. Table 6 provides a list of the ten queries and the aspect they can be categorized.

Table 6. The Aspects that Queries in a Sample Lesson Focus on Main idea What does the author mean here?

What is the author trying to say here?

How has the author settled this for us?

What’s the author’s message?

Character What has the author told us about the old miller?

How do things look for the old miller?

Given what the author has already told us about the old miller, what do you think he’s up to?

Judgment What does the author mean by using “two foolish people?”

Based on how the author described the old miller, does it connect with what the author told us before?

Response What do you think of that?

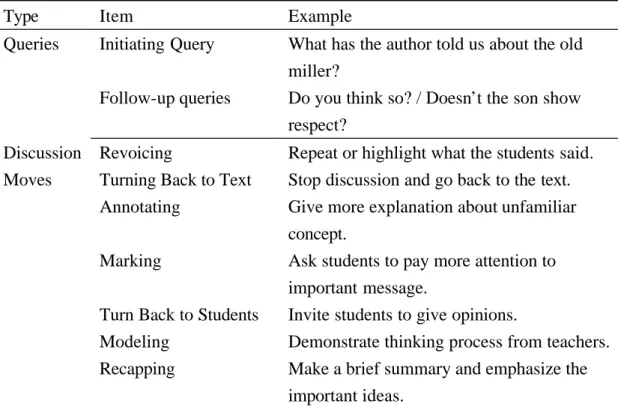

In order to keep an orderly process, making good use of six discussion moves, marking, re-voicing, turning back, modeling, annotating and recapping (See Table 7), was essential as well. These six discussion moves may not appear in discussions all the time, but the teacher had to know them well to cope with the active QtA lessons.

Table 7. The Queries and the Discussion Moves used in a Sample Lesson

Type Item Example

Initiating Query What has the author told us about the old miller?

Queries

Follow-up queries Do you think so? / Doesn’t the son show respect?

Revoicing Repeat or highlight what the students said.

Turning Back to Text Stop discussion and go back to the text.

Annotating Give more explanation about unfamiliar concept.

Marking Ask students to pay more attention to important message.

Turn Back to Students Invite students to give opinions.

Modeling Demonstrate thinking process from teachers.

Discussion Moves

Recapping Make a brief summary and emphasize the important ideas.

Note: The moves are sequentially ordered based on the development of this lesson.

A Lesson Excerpt. An excerpt of QtA lessons is given below to explain what a

QtA lesson is like and how discussion moves are used.

In this excerpt, the teacher read the third segment of the passage first. The segment is about how the miller felt when some old men criticized his son riding on the donkey. The miller cared about the old men’s opinions and was upset. The teacher led the discussion after reading the third segment of this story using the prepared Queries as starters for discussion.

The researcher first asked the Initiating Query “What has the author told us about the old miller?” She repeated, so all students would notice the query. After one student, Ann, expressed her idea, the researcher repeated what she said. The discussion move “re-voicing” (Beck et al., 1997, p. 85) was applied here. After the researcher re-voiced, she then asked Follow-up Queries like “Do you think so,” or

“Doesn’t the son show respect,” to bring about more discussion. In the excerpt, the words, phrases or sentences underlined are the translation of Chinese discourse in the discussion.

Teacher: Let’s look at question number three. What has the author told us about the old miller? What has the author told us about the old miler? [Initiating Query] Well, please translate the sentence.

Tom: Something about the old miller.

Teacher: Right! The author told us something about the old miller [revoicing]. What did he say? What did he say? Dave, are you ready to answer the question with a fan, (someone responds,

“excellent!”) or make a poem? Dave, Dave (not paying attention), anyone?

Ann: The son rides on the donkey.

Teacher: Yeah.

Ann: And people think the son doesn’t show respect.

Teacher: People think the son doesn’t show respect [revoicing], so…

Ann: So they think the father should ride on the donkey.

Teacher: The son doesn’t show respect. Do you think so? [Follow-up

Query]There is a donkey. The son is on the donkey and the father isn’t. Doesn’t the son show respect? [Follow-up Query]

Other discussion moves like “turning back to text” (p. 82) and “annotating” (p.

90) could be found in the second excerpt. The researcher asked students to “Let’s look at Line 10” for the confusing idea. What is more, she “annotated” by giving explanation that it is a contrast between young girls and old men.

Teacher: Right. What is confusing?

Frank: Teacher, he doesn’t understand the whole part.

Tom: Teacher, the party is outside. The old men had a party outside.

Teacher: the party? Very good. Tom mentioned about the party. “Soon they met another party.” Let’s look at Line 10. [turning back to the text]

“Soon they met another party.” “Party” here means a group of people, not the party to have fun. [annotating] And the party here doesn’t refer to young girls mentioned earlier, but refer to old men. It’s a contrast here. The author mentioned young girls talked nonsense and criticized others a lot. (One student: Disreputable women!)

The third excerpt showed “turning back to text,” “marking” (p. 81) and “turning back to students” (p. 83). The researcher first invited students to look at the text again and pointed out the difficult word. She highlighted the synonym of the old men, so students could look for it, construct meaning and say it. After asking “Who can find the word,” the researcher had students try to search for the important idea.

Teacher: Well, let’s come back to the text. The most difficult word in the segment is the word “party.” [marking] Tom mentioned it well. He thought it was an outside party. He was wrong. It referred to a group of people. Another part of the text is good, too. The old. There is one adjective word referring to old people in the part. Who can find the word? [turning back to students]

Meg: Poor.

Teacher: “Poor” means no money or deserves our sympathy. Sorry. What refers to the old? Anyone?

Sally: Gray head.

Teacher: Very good. “Gray head” refers to the old. In which line? In line 11, we have “shaking their gray head.” [turning back to text] “Gray”

means the color between black and white. Their hair has turned

white. Understand? So “gray head” means the old. Are the old doing such things? When they see something unpleasant, they shake their heads? Do your grandparents do the same thing?

The final excerpt contains two more discussion moves “modeling” (p. 86) and

“recapping” (p. 92). When the researcher expressed “I read this last night and found something strange. I wondered what happened,” she tried to describe how she thought and then students could learn the way. It might not be easy, but the researcher still had to demonstrate “think aloud” (Beck et al., 1997; Kucan & Beck, 1997) for students to learn to think. When the discussion almost came to an end, the researcher asked students to make a brief summary by recapping and emphasized the important ideas.

Teacher: Yes. Where is it? I read this last night and found something strange. I wondered what happened. [modeling] “That strong young boy riding easily on that donkey while his poor old father follows on foot.”

What’s so strange here?

Joe: We have “s” after the father.

Teacher: It is correct. The father is third-person singular. Do you find it? OK.

Let me tell you. The word “riding” is strange. The sentence misses one main verb. The author made a mistake here. You could do better than the author. That’s all for the section. Let’s look back the first three segments. What happened to these sections? They first met young girls. Next, they met old men. Who can tell us all this one more time? [recapping] Wow, this group is united. OK. Mike.

Mike: A father and a son wanted to sell the donkey. The donkey was in front of them. They met young girls. The father asked his son to ride on the donkey. Then they met the old men…

After ten segments were discussed, students had to do Comprehension Check (Appendix I) including nine multiple-choice questions and one open-ended question.

Control Group (hereafter Group C)

In Group C, the researcher taught the same passage for the two periods in each week. There are three steps in teaching for 83 minutes with each passage. First,

she explained new words for the passage. Second, the researcher read aloud each word and had students repeat the words three times. Third, after reading aloud the first half of the content, the researcher explained the sentence pattern, grammar points and translated the sentences. She then went on with the second half of the content.

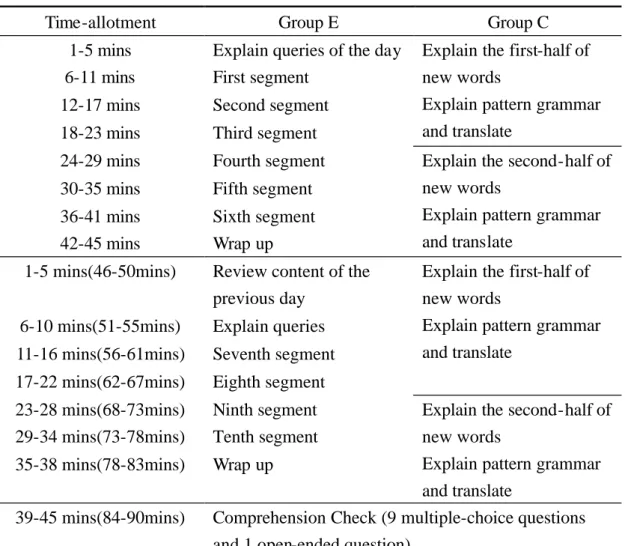

The remaining seven minutes was for Comprehension Check test, the same test as used with the experimental group. Table 8 displays a comparison of syllabus between Group E and Group C.

Table 8. A Comparison of Schedules between Group E and Group C

Time-allotment Group E Group C

1-5 mins Explain queries of the day 6-11 mins First segment

12-17 mins Second segment 18-23 mins Third segment

Explain the first-half of new words

Explain pattern grammar and translate

24-29 mins Fourth segment 30-35 mins Fifth segment 36-41 mins Sixth segment 42-45 mins Wrap up

Explain the second-half of new words

Explain pattern grammar and translate

1-5 mins(46-50mins) Review content of the previous day

6-10 mins(51-55mins) Explain queries 11-16 mins(56-61mins) Seventh segment 17-22 mins(62-67mins) Eighth segment

Explain the first-half of new words

Explain pattern grammar and translate

23-28 mins(68-73mins) Ninth segment 29-34 mins(73-78mins) Tenth segment 35-38 mins(78-83mins) Wrap up

Explain the second-half of new words

Explain pattern grammar and translate

39-45 mins(84-90mins) Comprehension Check (9 multiple-choice questions and 1 open-ended question)

Data Collection

Data collection was done one week before and one week after treatment. This section includes two parts. The first part is about the design of the pretest and

posttest and the second part concerns the data collection procedure.

Design for the Pretest and Posttest

The design for the pretest and the posttest is a split-block design (See Table 9).

Two sets of reading were used in the pretest and the posttest “The Foolish Friend” and

“The Prince and the Lion”. The experimental group and the control group were divided into two groups. The experimental group contained two subgroups, Group A and Group B while the control group also included two subgroups, Group A and Group B. For the pretest, Group A read the first passage “The Foolish Friend” and Group B read the second passage “The Prince and the Lion.” As for the posttest, Group A read “The Prince and the Lion” while Group B read “The Foolish Friend”

(See Table 9). With this counter-balanced design, the effect of text sequence on recall and comprehension would be minimized (Beck et al., 1996).

Table 9. A Design for Pretest and Posttest of Group E and Group C

Pretest Posttest

Group A “The Foolish Friend” “The Prince and the Lion”

Group B “The Prince and the Lion” “The Foolish Friend”

Data Collection Procedure

Both groups took the pretest one week before the treatment in their own classrooms and posttest the one week after the treatment was completed. Pretest and posttest procedures are the same except that Group E had to finish a Perception Questionnaire in the posttest. The procedure took 45 minutes to complete. First, students were given a folder with a story in it. They were asked to read the story for ten minutes and finished a written recall in Chinese for fifteen minutes. When they started doing the recalls, they were asked to cover the passage, i.e. the side with words faced down, on the table and waited for the researcher to collect them. Second, after

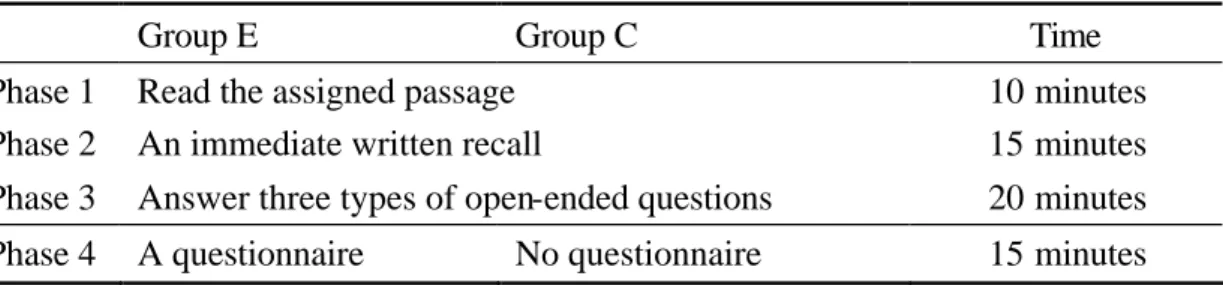

the recall sheets were collected, students were given a test paper with nine questions on one side and the same story on the other side for reference. When students answered three types of questions, they were allowed to read the text to reduce the memory-loss. They answered the questions for twenty minutes. In the posttest, Group E did one more task about a Perception Questionnaire. Table 10 shows the data collection procedure of the pretest for both groups.

Table 10. Data Collection Procedure of Both Groups

Group E Group C Time

Phase 1 Read the assigned passage 10 minutes

Phase 2 An immediate written recall 15 minutes

Phase 3 Answer three types of open-ended questions 20 minutes Phase 4 A questionnaire No questionnaire 15 minutes

Scoring

Scoring Retention in the Written Recall. The scoring of written recall was

based on Bernhardt’s (1991) “pausal unit” system, which requires the rater to read aloud the passage and mark places where one starts and ends with a pause (Alderson, 2000; Bernhardt, 1991; Chu, 2002). Thus, students’ recall sheets were examined against the unit system to see whether the units were “present or absent” (Alderson, 2000, p. 231).

Two native speakers of English read both passages of test materials to themselves to mark all the places in the text where they took a breath. Comparing the markers, the researcher chose the narrower units as the basis for scoring. The resultant passages contained 41 units and 40 units, for pretest and posttest respectively (Appendix J). Each unit was given one point. No partial point was given. The researcher and one English teacher in the same school scored all the copies (124 copies) blind against the pausal unit system (Chu, 2002). All the points were

transformed by percentage. The interrater reliability was .98. Different opinions reached a consensus through discussion.

Scoring of Inference in the Written Recall. In addition to units that match the

units in the pausal unit system, there were idea units that failed to match the textual ideas. They were classified as inferences because they might be evidence as inferences that participants inferred in the process of reading or as misconstrued ideas.

While participants were doing written recalls, they were likely to produce something which was not stated in passages. Therefore, the researcher re-coded the residue of the written recall into three types of inferences: text-based inferences, reader-based inferences, and incorrect inferences. One propositional unit was taken as one point for the frequency of the types of inferences.

Text-based inferences were inferences generated on a basis of text information, either increasing on the original message or reducing through summarizing.

Reader-based inferences were inferences based on personal experience or knowledge.

Incorrect inferences were inferences due to misreading or wrong information (Barry

& Lazarte, 1998; Chu, 2002). The researcher scored all of the written recall for the units that were not identical to the original text. A second rater, who rated all the written recalls, scored one fifth of the copies. The interrater reliabilities for text-based, reader-based and incorrect inferences were .92, .85 and .96, respectively.

Disputed coding came to general agreement through discussion.

Some examples for three types of inferences were: There was a king. He won the land and won his enemy (text-based inference); He was very tired, so he wanted to

take a rest (reader-based inference); Then the king saw they were having a contest (incorrect inference).

Scoring of Three Types of Comprehension Questions. The scoring of three

types of open-ended questions was based on completeness and relevance of the text

and possible interpretation connecting the text (Alderson, 2000). Each of students’

responses was scored holistically from 0 to 4 (Soang, 2002). As there are nine questions for each passage, the total of the score is 36. The answer that provides no information or irrelevant information was given a zero. One point was for scanty information. Two points were for limited information concerning the text. Three points were given for enough information but no elaboration. When the answer shows fluent expression and clear ideas, the highest score, four points, was given.

The researcher and a second rater, an experienced English teacher, scored all the copies blind. The interrater reliabilities for factual, interpretive and responsive questions were .97, .91 and .91, respectively.

Data Analysis

The data collected in the study were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively to answer the research questions.

Quantitatively, a computer statistical program SPSS for Window was applied to compare group differences for the data collected from the pretest and the posttest.

To answer the first research question, percentage of pausal units recalled from both groups were compared using ANCOVA to test the effect of QtA lessons on retention in the written recall. The independent variable is Group and the covariate variable is pretest recall. Besides, the frequency of three types of inferences— text-based, reader-based, and incorrect inferences— were analyzed respectively using ANCOVA.

Thus three rounds of ANCOVA were performed on each type of inference, with pretest as a covariate variable, inference as a dependent variable.

For the answer to the second research question, ANCOVA analysis was employed as well. Again, three rounds of ANCOVA were done on three types of comprehension question –factual, interpretive and responsive— respectively, with

pretest as a covariate variable and score for each type of questions as a dependent variable.

To answer the third research question, the response from the questionnaire was analyzed by percentage and the last open-ended question was analyzed qualitatively.