Chapter Two

Literature Review

Conditional (if-then) constructions directly reflect the characteristically human ability to reason about alternative situations, to make inferences based on incomplete information, to imagine possible correlations between situations, and to understand how the world would change if certain correlations were different.

(Ferguson et al. 1986: 3)

Ferguson et al. begin their volume On conditionals with the above sentence, which shows that conditional sentences directly reflect the language users’ ability to reason about alternatives, uncertainties and unrealized contingencies. An understanding of the conceptual and behavioral organization of this ability to construct and interpret conditionals provides basic insights into the cognitive and linguistic processes of human beings.

The question of what a conditional construction is may be answered in different ways and from different perspectives, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy. In the earlier studies (especially in the philosophy tradition), ‘logic’

plays an important role as the defining basis for conditionals. The meaning attributed

to conditionals in these studies is most often seen as truth-conditional. In logic,

conditionals (material implications) are defined as a relation between two

propositions, the protasis (p) and the apodosis (q), such that either p and q are both

true, or p is false and q is true, or p is false and q is false. This use of material

implication, however, is widely recognized as defective, because in actual utterances

in actual contexts, the interpretation of a conditional may be more restrictive than

this. In actual utterances, we usually exclude the possibility of ‘p is false and q is

true’ (cf. Geis and Zwicky 1971: 562, Comrie 1986: 78, Fillenbaum 1986: 182,

Konig 1986: 236, Dancygier 1998: 14). That is to say, users of natural languages tend to reject the validity of false antecedent implying true consequent. Thus, if someone says ‘If you go out without the umbrella, you’ll get wet’ (Comrie 1986: 78), then the normal interpretation is that if the addressee does take the umbrella, then s/he will not get wet. This is not part of the logical meaning of the conditional, but only a conversational implicature, which can be derived from other aspects of the interpretation of the sentence in context. Geis and Zwicky (1971:562) have called this phenomenon ‘conditional perfection’ and formulated it as follows: “A sentence of the form X⊃Y invites an inference of the form ~ X⊃~Y”.

A Gricean explanation in terms of conversational assumptions has been given to account for such a phenomenon (cf. Geis and Zwicky 1971: 562, Comrie 1986: 78, Fillenbaum 1986: 182, Konig 1986: 236, Dancygier 1998: 14). The weaker statement ‘if p, q’ and its more categorical counterpart ‘q (anyway)’ form a scale: < q (anyway), if p, q>. On the basis of the maxim of quantity, the addressee assumes that the speaker says no less than is appropriate to the circumstances. In other words, the addressee bears the assumption that the strongest possible assertion has been made.

So the assertion of the weaker statement ‘if p, q’ will give rise to the implicature ‘~q (anyway)’ and thus to the inference that p is a necessary condition for q. Going back to the umbrella example provided by Comrie, we know that the only coherent interpretation of the utterance is as a warning to take the umbrella to prevent getting wet. If the speaker saying If you go without the umbrella, you’ll get wet knows that the umbrella has so many holes that it won’t keep the addressee dry, then the speaker has violated the maxim of quantity.

Due to the discrepancy between formal logic and real language use, in defining

the notion ‘conditionality’, many linguists have shifted their attention from the logical

truth condition to the pragmatics of conditional constructions.

Our review, then, will focus on the pragmatic aspects of conditionals. We will start with the communicative function of conditionals as ‘non-assertion’, and then move on to the motivation for non-assertion in the discourse. After that,

‘hypotheticality’, a notion closely related to non-assertiveness, is introduced.

Correlation between conditional and temporal clauses, which involves the notion hypotheticality, is also discussed. Finally, some works on Mandarin conditionals will be examined.

2.1 Conditional as Non-Assertion

Comrie (1986) points out that in a conditional if p then q, there is no statement of the truth of either p or q. The following dialogue serves as illustration:

(2.1) A: I’m leaving now.

B: If you’re leaving now, I won’t be able to go with you.

(Comrie 1986: 79)

B’s utterance, in this dialogue, may receive the interpretation ‘Since you’re leaving now, I won’t be able to go with you’, which means B is fully accepting that A is indeed leaving now. However, the truth of ‘A is leaving now’ is not part of the meaning of the conditional sentence, but is deduced from the context. Therefore, he (1986: 89) concludes that:

A conditional never involves factuality—or more accurately, [that] a conditional

never expresses the factuality of either of its constituent propositions. That one

or other of the propositions is true may be known independently of the

conditional, for instance from the rest of the verbal context or from other sources,

but this does not alter the crucial fact the conditional itself does not express this

factuality.

Following the same line of reasoning, Comrie moves on to make a controversial claim that English lacks true counterfactual conditionals, viz a conditional construction from which the falsity of either protasis or apodosis can be deduced logically. He uses the following example to support his claim that counterfactuality is not part of the meaning of the apodosis:

(2.2) If the butler had done it, we would have found just the clues that we did in fact find.

(Comrie 1986: 90)

Comrie suggests that the final clause of the example above indicates we did find the clues in question. That is, the apodosis is true. What’s more, the sentence leaves open the possibility that the butler did indeed do it. Examples like this are cited for his point that counterfactuality is in fact merely an implicature and can be cancelled in the context.

Comrie’s (1986: 80) claim that “from a conditional the falsity of either p or q cannot be deduced” has been challenged by Wierzbick (2002), who proposes that English does have at least one specific frame to mark ‘true counterfactuals’. She admits that there may be some doubt about the affirmative sentences (if+pluperfect+would), in which the counterfactuality can be cancelled by the saving context, as Comrie points out in example (2.2). But she contends that the negative counterfactuals (if+pluperfect+Neg.+would) clearly do signal semantic

‘counterfactuality’, as the following example shows:

(2.3) If they hadn’t found that water they would have died.

(2.4) *If they hadn’t found that water, they would have died; so let’s hope they found it.

(Wierzbicka 2002: 29-30)

Wierzbicka reports that among English native speakers whom she has interviewed, she has not found any who would not regard example (2.3) as counterfactual. In other words, the counterfactuality of example (2.3) is not an implicature and thus cannot be cancelled by a saving context. As a result, example (2.4) is rejected.

Aside from his problematic claim about the status of counterfactuality, Comrie is important in providing an insightful perspective on conditionals—to approach the truth/falsity of propositions in conditional construction from its function (i.e.

expressing speaker’s non-commitment to the propositions) but not from the logical truth condition, and to acknowledge the role of context in our understanding of conditionals.

Like Comrie, Akatsuka (1986) shows that the concept of ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’ in conditionals depends crucially on context and speaker’s viewpoint. She provides the following example for illustration:

(2.5) Pope phones a telephone operator in a small Swiss village Pope: I’m the Pope

Operator: If you’re the Pope, I’m the Empress of China!

(Akatsuka 1986:334)

According to logic, the two ps (i.e. ‘I’m the Pope’ and ‘you’re the Pope’) convey the

same propositional meaning, and therefore it is impossible to assign different truth

values to each of them. In this example, however, Pope obviously believes p to be true,

while the operator makes it clear that s/he believes it to be false. As Akatsuka points

out, examples like this shift the question of the truth or falsity of conditional clauses

to a different level of analysis—what the speaker is communicating with

conditionals—in which the ‘speaker’s attitude’ and the ‘context’ have to be taken into

consideration.

Another issue related to this example is why the operator chooses to employ a conditional form in reaction to Pope’s utterance. Akatsuka makes it clear that

‘information’ (if p) must be differentiated from ‘knowledge’ (p): only the former belongs to the domain of conditionals. The p ‘You’re the Pope’ is a quotation of the

‘new information’ which has been just ‘given’ to the operator by Pope. And the q ‘I’m the Empress of China’ is the operator’s reaction to the newly provided information p.

Since ‘you are the Pope’ is not part of the knowledge of the operator, s/he chooses to quote p by if, showing his/her uncertainty/uncontrollability of p.

Akatsuka (1986) contributes to our understanding of the pragmatics of conditionals in that she, like Comrie (1986), incorporates discourse into the analysis of the truth/falsity of conditional propositions. She points out that the analysis of conditionals in terms of truth values is defective in explaining conditionals in real language use (such as the example cited above), for the major concern of logicians has been truth values, virtually no attention has been paid to the speaker’s attitude towards p and q. By appealing to such notions as prior contexts in the discourse and the speaker’s attitude towards what the interlocutor has just said, Akatsuka successfully provides a thorough account of our understanding of the semantics and workings of conditionals. In addition, Akatsuka’s position that the prototypical meaning of ‘if p’ is the speaker’s uncertainty/uncontrollability of p also captures the precise characterization of conditionals as ‘non-assertive/hypothetical’.

Similar to Comrie (1986) and Akatsuka (1986), Dancygier (1988) recognizes

the problem of truth-conditional studies and rejects the treatment of if solely as a

logical connective. Instead, she asserts that if “is a marker of non-assertiveness and its

presence in front of an assumption indicates that the speaker has reasons to present

this assumption as unassertable” (Dancygier 1988: 23). In other words, Dancygier

identifies conditional construction with non-assertion and proposes that the clauses of a conditional should not be treated as assertions of true or false propositions.

Dancygier refers to Seale’s definition (1969) of the speech act of asserting and points out the felicity conditions for the speech act of asserting “require that the speaker have evidence to support her belief and actually believes the assumption to be true”

(Dancygier 1988: 18). While the act of ‘assertion’ counts as the speaker’s commitment to the truth of a proposition, non-assertive utterances like conditionals, on the other hand, are used to express assumptions which need to be entertained or considered, but cannot be asserted felicitously. The reasons for non-assertion may vary, but what remains constant is that while employing conditional constructions, the speaker feels the need to distance him/herself from the assumption in question and does not commit him/herself to the statement.

Dancygier’s treatment of if as a marker of non-assertiveness, but not as a pure logical connective, has again shifted our attention from the truth table to the pragmatic factors of conditionals, mainly to the ‘communicative function’ of the conditional construction.

Closely related to Dancygier’s idea of if as a marker of non-assertiveness is the notion of ‘conditional mental space’, which is initiated by Fauconnier (1985). Mental spaces are “constructs distinct from linguistic structures but built up in any discourse according to guidelines provided by the linguistic expressions” (Fauconnier 1985: 16).

A speaker may build up an understanding of some state of affairs, and then the hearer is guided by the speaker’s language to set up mental constructs parallel to those of the speaker. The linguistic expressions which typically establish new spaces are called

‘space-builders’. If p is one kind of space-builder. Linguistic forms such as if p, then q

set up a new space H in which p and q hold. The kind of space set up by if is

hypothetical. This is schematized as follows:

Parent space R Hypothetical space H Space-builder: if P Holds in H :Q Semantics: Q holds in all P-situations.

(Cancellable) implicature: Q holds only in P-situations.

(Fauconnier 1985: 115)

What is critical about Fauconnier’s theory is that the hypothetical mental space is set up to serve the communicative goal of hypothetical thinking, but not for the evaluation of truth values. He argues that there is no point in trying to evaluate the truth of the following statements ‘If Napoleon had been the son of Alexander, he would have been Macedonian /If Napoleon had been the son of Alexander, he would not have been Napoleon’ (Fauconnier 1985: 118) because there is no ‘absolute’ truth when only some facts and laws (such as ‘same nationality for father and son’,

‘different parents, different offspring’) are imported into the hypothetical space to carry out a specific reasoning. Therefore, whether there is a possible world in which the above sentences are true or not has no bearing on their linguistic status. What matters is that these conditional constructions, which make our hypothetical reasoning possible, are used to indicate that the apodosis holds true in the same mental space as the mental space defined by the truth of the protasis.

Fauconnier’s theory of mental spaces (1985) provides us with a cognitive

perspective on conditional constructions. The theory corresponds to the descriptive

approaches taken by Comrie and Akatsuka in recognizing conditional construction as

non-assertion. According to Fauconnier, if, as a builder of the ‘hypothetical space’, plays a specific role as a lexical exponent of the conditional constructions in which the protases and apodoses are interpreted non-assertively/hypothetically. With conditional constructions, we are able to perform different kinds of mental operations in the irrealis world.

The framework of mental spaces is at a later time adopted by Dancygier and Sweetser (2005) in their elaborate discussion on conditionality. Conditional constructions, according to Dancygier and Sweetser, vary widely in function. And Mental Spaces Theory enables us to attribute some of this functional diversity to a few specific parameters of interpretation. For example, Mental Spaces Theory provides a simple mechanism for the description and analysis of the difference between predictive and non-predicitve conditionals (such as speech act conditionals)

1.

Comrie (1986), Akatsuka (1986), Dancygier (1988), Fauconnier (1985), and Dancygier and Sweetser (2005) have all shown that the traditional truth-conditional accounts of conditional construction is less-than-satisfactory, for they cannot account for the actual processes of arriving at particular interpretations of particular conditionals in particular contexts. These researches, then, have clearly demonstrated an attention from the truth-conditions to the pragmatic aspects of conditionals, and have successfully indicated that what is of true importance about conditionals is their communicative function: to enable the speaker to make a non-assertion and to induce hypothetical reasoning.

2.2 Motivation for Non-Assertion

What follows the acknowledgment of conditionals as non-assertion is the

1 More detailed discussion about the correlation between different kinds of conditionals and different types of mental spaces is presented in Section 2.2.

question: for what reasons does the speaker choose to mark an assumption as non-assertive? As indicated above, conditional connectives such as if are not logical operators; rather, they are adopted as conversational strategies. Expressing an assumption by a conditional construction indicates that the speaker has reasons to present his/her assumption as unassertable. The reasons may vary. Many studies have tried to explain and explore these reasons. Among others, Dancygier (1998) gives a systematic account of this question. Therefore the following review is mainly focused on Dancygier’s study, accompanied by similar notions provided by other researchers.

Dancygier (1998:110) argues that the marker if instructs the hearer to treat the assumption in its scope as not assertable in the usual way. She comes up with three types of reasons for the speaker to mark an assumption as non-assertive. The first type is related to the speaker’s state of knowledge. When the proposition is ‘not knowable’,

‘not factual’ or ‘not predictable’ for the speaker, s/he would introduce the proposition

in the conditional construction to show his/her lack of commitment to the assumption.

The second type of non-assertiveness is found in the conditionals with the

so-called ‘contextually given p’ (cf. Akatsuka 1986: 339), where the protasis contains

an assumption which is acquired by the speaker indirectly. Since the assumption is not

known to the speaker directly, s/he then uses if to mark his/her epistemic distance to

the assumption. This concept of ‘contextually given p’ has been mentioned in many

other studies, such as Akatsuka (1986), Comrie (1986: 89, 91), Ford and Thompson

(1986: 356), and Van der Auwera (1986), Akatsuka (1986: 339-41) goes particularly

deep into this issue. She divides ‘contextually given p’ into two sub-types: new

information and unsharable knowledge/belief. The Pope/operator dialogue cited in

Section 2.1 belongs to the first type, in which the quoted p is the new information

which has been just ‘given’ to the speaker at the discourse site. The example is

repeated below:

(2.6) Pope phones a telephone operator in a small Swiss village Pope: I’m the Pope

Operator: If you’re the Pope, I’m the Empress of China!

(Akatsuka 1986:334)

Since ‘you are the Pope’ is not part of the knowledge of the operator, s/he chooses to quote p by if, showing his/her uncertainty/uncontrollability of p. As for the second type, i.e. unsharable knowledge/belief, the following two dialogues serve as illustrations:

(2.7) (A mother and her son are waiting for the bus on a wintry day. The son is trembling in the cold wind.)

a. Son: Mommy, I’m so cold!

b. Mother: Poor thing! If you’re so cold, put on my shawl.

(She puts her shawl around his shoulders).

(2.8) Son (looking out of the window): It’s raining, Mommy.

Mother: If it’s raining (as you say), let’s not go to the park.

(Akatsuka 1986: 340-41)

In dialog (2.7), though the mother regards p to be factual, it is newly learned

information to her rather than her own knowledge. The inner world of consciousness

of other people belongs to unsharable knowledge, no one can enter other people’s

minds and directly experience their feelings, emotions, or beliefs, and therefore, p is

expressed in the form of if p. Similar account applies to dialog (2.8), in which the

mother, being an external observer rather than the actual experiencer (because she

does not look out of the window to check whether it is really raining or not), marks p

with if to show her epistemic distance from the proposition p. The observation that p

and if p are ‘epistemologically distinct’ (Akatsuka 1986: 341) echoes the ‘epistemic

distance’ mentioned by Dancygier (1998: 113). When the assumptions are not

presented by the speaker as known to him/her, they are marked with distance (by if).

The third type of non-assertion is associated with conversational conditionals, or speech act conditionals. Such conditionals are presented to the hearer as only tentative, “for they express conditionals on the appropriateness of the apodoses and refer to the rules of politeness and linguistic usage that the hearer may not share”

(Dancygier 1998: 110).

With regard to the interaction between conditionals and speech acts, Van der Auwera (1986) and Sweetser (1990) both point out that if-clauses can bear a relationship to the speech act performed in the main clause. The protases of the following sentences are said to guarantee a successful performance of the speech act in the apodosis:

(2.9) If I can speak frankly, he doesn’t have a chance

(2.10) Where were you last night, if you wouldn’t mind telling me?

(2.11) Open the window, if I may ask you to

(Van der Auwera 1986: 199)

Van der Auwera (1986) calls (2.9)-(2.11) ‘conditional speech acts’ and defines them as sentences in which the protasis is asserted to be a sufficient condition for a speech act about the apodosis. Sweetser (1990) refers to sentences like (2.9)-(2.11) as conditionals in the speech act domain, or ‘speech act conditionals’.

In either interpretation (Van der Auwera or Sweetser) the protasese of such

sentences are largely independent of the content of their apodoses, and the

propositional content of the sentence does not contain assumptions of causality

between the states of affairs described. Therefore, they do not belong to the content

domain or to the epistemic domain, but are characterized into the speech act domain

2. Sweetser (1990) treats this kind of conditionals as being causal on a different level:

the state described in the protasis may be seen as causing or enabling the speech act in the apodosis.

However, as Sweetser notes, the intended speech acts are in fact performed, not just performed conditionally. Even if the hearers of utterances like (2.9)-(2.11) are uncooperative and say something like ‘No, you can’t speak frankly’, ‘Yes, I do mind telling you’, or ‘No, you may not ask’, this would be interpreted as a rejection to speaker’s comment or a refusal to give an answer or act, but not as invalidating the condition on which the speech act was supposedly contingent. Also, the hearer can reject the condition and still react positively to the speech act.

Recognizing the limitation which Sweetser’s speech act category suffers from, Su (2004) argues that if-clauses in speech act conditionals do not in fact suspend the performance of the speech act intended in the apodosis, but function to give the hearer some option in reacting to the speech act performed, to make the utterance more polite or appropriate. Examples such as

我很討厭她,如果你不介意我說實話的話(Su 2004: 305) are actually used mainly for the purpose of managing politeness. In examining Chinese conditionals in spontaneous spoken discourse, Su pinpoints the important role played by context and the concern over politeness in the interpretation of conditionals. The prototypical function associated with the use of conditional—to decrease the assertibility of a statement—makes conditional construction a good way to hedge a potentially face-threatening situation.

Though Auwera and Sweetser spot special status of the speech act conditionals,

2 Sweetser(1990) has argued that conditionals are interpretable as joining clauses in different ways and can thus be classified into three different domains: the content domain, the epistemic domain, and the speech act domain.

they fail to recognize the fact that these speech act conditionals are actually used for politeness sake, which is pointed out in Su’s study.

Speech act conditionals, in Dancygier and Sweetser’s term (cf. Dancygier 1998, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005), are non-predictive conditionals, as opposed to predictive conditionals. Mental Spaces Theory is employed to differentiate the two types of conditionals. In a predictive conditional, someone is predicting something, but only conditionally upon some unrealized event. In such conditionals, mental spaces are set up for the interlocutors to imagine ‘alternatives’ (Dancygier and Sweetser 2005: 31). For example, the sentence If you mow my lawn, I’ll pay you ten dollars (Dancygier and Sweetser 2005: 31) represents two alternative mental-space set-ups—one contains an if space, in which the lawn is mowed and its extension space, in which ten dollars is paid; the other, alternative set-up has spaces in which the lawn is not mowed and ten dollars is not paid. The conditional predictive function is an important one in human cognition and communication, and every language has some way of expressing this function—everyday human decision-making constantly involves conceptualization of a scenario wherein some action has been taken, and imagination of the possible results. On the contrary, non-predictive conditionals such as speech act conditionals are less canonical and central members of the conditional category. When a speaker uses a speech act conditional such as If you need any help, my name is Ann (Dancygier and Sweetser 2005: 110), she doesn’t intend to set up for her hearer two alternative spaces, one in which the hearer needs help and the speaker’s name is Ann, and the other in which the hearer needs no help and the speaker’s name is something else. Rather, the protasis is used to specify the mental-space background against which the offer (embodied by the apodosis) is made.

The sentence is making an offer (in a hedged manner), not predicting an offer.

To sum up, though the reasons for non-assertion vary, they can be categorized

into three types. The first reason for non-assertion is to mark the speaker’s state of knowledge (when the proposition is ‘not knowable’, ‘not factual’ or ‘not predictable’

for the speaker), and conditionals of this kind serve predictive function (Dancygier 1998, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005), which is the central one in the network of functions filled by conditional forms. The second reason for not engaging in full-assertion is to express the speaker’s epistemic distance to the propositions in the protasis—when p is contextually grounded, may it be new information or unsharable knowledge/belief (Akatsuka 1986, Comrie 1986: 89, 91, Ford and Thompson 1986:

356, Van der Auwera 1986, Dancygier 1998), the speaker chooses to frame p by a conditional protasis to signal that p is not known directly to him/her. Conditionals of such type are mostly non-predictive conditionals, whose function is simply to give background to the addressee, by invoking the relevant parts of the cognitive context which brought about this conclusion, as shown in the examples (2.6)-(2.8) above. The last reason for non-assertion is that the speaker wants to perform speech acts via conditionals (Van der Auwera 1986, Sweetser 1990, Dancygier 1998, Su 2004, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005), in which the protasis appears to conditionally modify not the contents of the apodosis, but the speech act which the main clause carries out.

Such conditionals are non-predictive, too—p is not the basis of the prediction in q;

rather, p is used to specify the background against which the speech act in q can be felicitously performed.

The discussion so far has been focused on the cognition-based motivations

(relating to speakers’ state of knowledge or epistemic distance, or with regard to

metalinguistic functions speakers want to perform) for making non-assertion. Ford

and Thompson (1986), on the other hand, approach conditionals by analyzing their

discourse structures. In doing so, they provide an enlightening discussion of the

discourse function of conditionals. Examining English conditionals in written and

spoken discourse data, they find that initial conditionals create backgrounds for subsequent propositions. Furthermore, in terms of their relation to the preceding discourse, initial conditionals can be classified into four basic types: assuming, contrasting, illustrating particular cases, and exploring options. An ‘assuming’

conditional makes explicit an assumption present in the preceding discourse, as the following example shows:

(2.12) D: Well, didn’t you tell me last night at supper that you were disturbed about it [a letter] going out?

M: I’m very much disturbed and…

D: Well, that’s what I thought.

M: Well, I…

D: You were—if you were disturbed, you needn’t announce to the Press that—express surprise that we didn’t like it.

(Ford and Thompson 1986: 363)

A ‘contrasting’ conditional offers an alternative to a preceding assumption. Clauses following the contrasting if-clause take the situation introduced in that clause as their background. The following example has such a contrasting if-clause:

(2.13) B: Do you want to write a letter to the Director of the Budget?

M: No. I won’t write any letter. If I do I will say I am opposed to it.

(Ford and Thompson 1986: 364)

An ‘illustrating’ conditional provides a particular case of an abstract idea under discussion. In the next example, an abstract concept is made more concrete through an illustration:

(2.14) One point may be worth repeating, that the Fund is always worth the

same amount in gold; it always has the same value. If you start with an

eight billion dollar Fund, it is always worth eight billion. If currency depreciates, either by one circumstance or another, or if there should be a default or liquidation, a country has to put in more of its currency to make up for the difference. So that money in the Fund is always worth the same amount. It is always worth eight billion dollars.

(Ford and Thompson 1986: 364)

An ‘exploring options’ conditional opens up options, but does not restate or contradict what has come before it in the discourse, as shown in the following example:

(2.15) (Discussing ‘borrowing an employee’)

M:…I want him for his professional knowledge of finance and banking.

O: Yes.

M: And if I say to you that I want him for a year and you say, ‘Now, please don’t come to me in December and beg me to make it another year’—why I won’t do it, that’s all.

(Ford and Thompson 1986: 364)

In addition to the four basic types of connection that an initial conditional can bear to the preceding discourse in both written and spoken English, there is one type that occurs only in the spoken data: the conditional expressing a polite directive. Ford and Thompson argue that one reason for conditionals to encode polite directives may be due to a combination of their softening effect of hypotheticality and the fact that they seem to imply an option with alternatives. In the following example, M gives a polite directive to T, who responds with assent:

(2.16) M: If you could get your table up with your new sketches just as soon as this is over I would like to see you.

T: All right. Fine.

(Ford and Thompson 1986: 365)

Among the researches which focus on exploring the discourse functions of the conditional construction, Ford and Thompson’s study is probably the first one that is based on actual, rather than constructed or experimental, data. In order to understand how conditionals are used, authentic, naturally occurring data are essential because they help us to see what types of conditionals occur and how they relate to their discourse contexts.

2.3 Hypotheticality

As pointed out in the preceding section, the most prototypical function of conditionals is to mark speakers’ lack of knowledge (cf. Dancygier 1998, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005). Following that, without well-justified knowledge, speakers cannot make full-commitment to the state of affairs in conditionals. That is, the speaker uttering a conditional sentence is not ready to back up the proposition of either the protasis or the apodosis with evidence. Thus, conditionals, as one kind of non-assertion, are uncertain and hypothetical in essence, which involve hypotheticality.

Languages vary in their grammatical forms for distinguishing hypotheticality in the conditional construction. The distinction may be made by different markers for the protasis, as in the two conditional markers in ‘if’ (noncounterfactual) and law ‘if’

(counterfactual) in Arabic (Ferguson et al. 1986: 6); or by special patterns of tense/aspect forms, like the tense-backshifting in English. In the following review, we will focus mainly on English conditional sentences and see how different degrees of hypotheticality can be shown by different tense forms and various conditional connectors.

Comrie (1986) gives an elaborate definition of hypotheticality:

By the term ‘hypotheticality’, I mean the degree of probability of realization of the situations referred to in the conditional, and more especially in the protasis. I shall use the convention that ‘greater hypotheticality’ means ‘lower probability’

and ‘lower hypotheticality’ means ‘greater probability’. Thus a factual sentence would represent the lowest degree of hypotheticality, while a counterfactual clause would represent the highest degree.

(Comrie 1986: 88-89)

After defining ‘hypotheticality’ on the basis of ‘the degree of probability of realization of the situations referred to in the protasis’, Comrie (1986:88) then suggests that languages display a ‘continuum of hypotheticality’. Different languages simply distinguish different degrees of hypotheticality along this continuum.

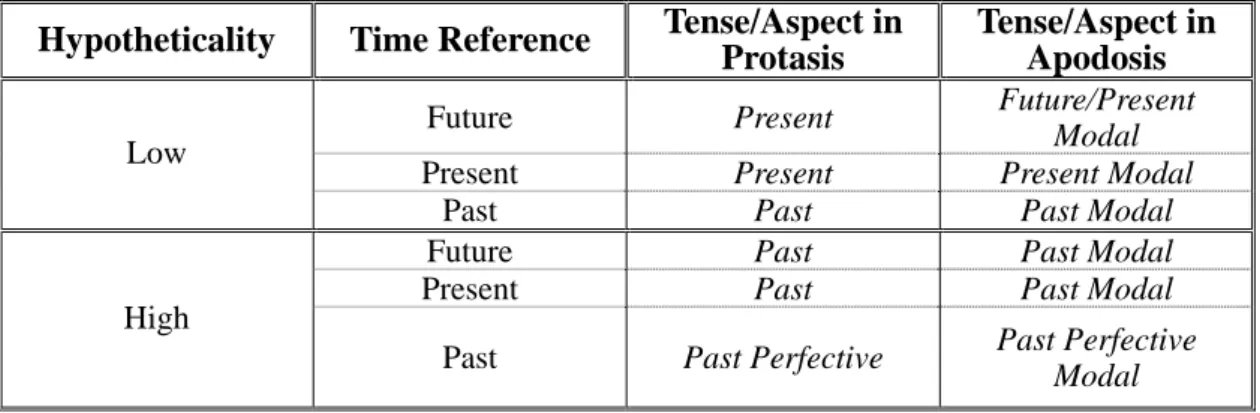

Generally speaking, a language has at least two different degrees being formally distinguished. English, according to Comrie, makes a two-way distinction between lower and greater hypotheticality. The distinction is expressed by the presence/absence of the tense-backshifting, which involves the notion of ‘time reference’. Time reference refers to the temporal interpretation of the event/state contained in the protasis. There are three kinds of time reference—future, present, and past. The following table

3shows the relationship between time reference and hypotheticality.

3 The table is made by us according to Comrie’s discussion on the relationship between time reference and hypotheticality.

Table 2.1 Relationship between time reference and hypotheticality in English conditionals

Hypotheticality Time Reference Tense/Aspect in Protasis

Tense/Aspect in Apodosis

Future Present Future/Present

Modal

Present Present Present Modal

Low

Past Past Past Modal

Future Past Past Modal

Present Past Past Modal

High

Past Past Perfective Past Perfective Modal

Lower hypotheticality involves the indicative without any backshifting in tense, as the following examples show:

(2.17) a. If you come tomorrow, you’ll be able to join us on a picnic (with future time reference)

b. If the students come on Fridays, they have oral practice in Quechua.

(with present time reference)

(2.18) If the students came on Fridays, they had oral practice in Quechua.

(with past time reference) (Comrie 1986: 92)

The past tense is used only if there is indeed past time reference (example (2.18)), and the present tense is used with present time reference (example (2.17b)). As for conditionals with future reference (example (2.17a)), they are, like conditionals with present reference, marked with present tense form in the protases. In other words, in English conditionals, the opposition of present/future reference is neutralized in the protasis—in both cases the present tense is used to mark the lower hypotheticality.

Greater hypotheticality, distinct from lower one, involves tense backshifting, as

in:

(2.19) a. If you came tomorrow, you’d be able to join us on a picnic.

(with future time reference)

b. If the students came on Fridays, they would have oral practice in Quechua.

(with present time reference)

(2.20) If the students had come on Friday, they would have had oral practice in Quechua.

(with past time reference) (Comrie 1986: 92)

Again, we find the neutralization of the present/future opposition in the protasis.

Comrie is insightful to make the point that degrees of hypotheticality do not have a clear-cut boundary among one another. Rather, hypotheticality is a continuum, in which different languages employs different ways (such as verb forms and lexical markers, etc.) to mark different degrees of hypotheticality.

Comrie, however, makes a false claim about Mandarin. He considers Mandarin as an apparent exception to his suggestion that languages distinguish different degrees of hypotheticality along this continuum. He says:

It should be noted that there are some languages which make no distinction in terms of degrees of hypotheticality, for instance Mandarin, where Zhangsan he-le jiu, wo jiu ma ta can cover all of ‘If Zhangsan has drunk wine, I’ll scold him’, ‘If Zhangsan drank wine, I would scold him’, ‘If Zhangsan had drunk wine, I would have scolded him’.

(Comrie 1986: 91)

On the basis of the sentence Zhangsan he-le jiu, wo jiu ma ta, which may indicate

both lower and higher degrees of hypotheticality, Comrie claims that Mandarin does

not make distinction in terms of hypotheticality. However, as native speakers of

Mandarin Chinese, we are skeptical of the accuracy of Comrie’s observation.

Sentences like Zhangsan he-le jiu, wo jiu ma ta in Mandarin may of course be open to more than one interpretation (because Mandarin does not make distinctions in the auxiliary verbs and tense as English does), but it doesn’t follow that Mandarin has no way of making the distinction between different degrees of hypotheticality. As will be shown in our later discussion (Section 2.5 and Chapter Four), in both Mandarin and Taiwanese, degrees of hypotheticality are actually marked mainly by different lexical conjunctions (cf. Arabic conditional conjunctions).

Comrie (1986) is not the first researcher who makes clear the correlation between tense and hypotheticality in English conditionals. Fauconnier (1985) points out that in English conditionals, tense variation has great effect on the space-builder if:

(2.21) If Boris comes tomorrow, Olga will be happy.

(2.22) If Boris came tomorrow, Olga would be happy.

(2.23) If Boris had come tomorrow, Olga would have been happy.

(Fauconnier 1985:111-12)

Fauconnier argues that while all these sentences express the same ‘logical’ connection

‘Boris coming tomorrow’ (the protasis B) and ‘Olga being happy’ (the apodosis O), they differ in their interpretations of the protases. (2.21) can be used either if B is taken to be valid (we know for sure that Boris is coming, and if he’s coming, Olga will be happy or if B is underdetermined with respect to the parent space (B?R) at the point in the discourse. However, (2.22) is used if B is underdetermined or if ~B is established, while (2.23) is only used counterfactually, i.e. it entails ~B.

Though without the term ‘hypotheticality’ specified, Fauconnier’s illustration of

the correlation between tense and the status of protases in English conditionals

corresponds to Comrie’s (1986) suggestion that tense backshifting is the best indicator

for different degrees of hypotheticality. Applying Comrie’s definition of hypotheticality to examine the status of the protasis B in sentences (2.21)-(2.23) above, we find (2.21) of the lowest hypotheticality and (2.23) of the highest one, with (2.22) placed in the middle.

It should be noted that while Comrie proposes a two-way distinction in terms of hypotheticality, Fauconnier’s examples actually reveal a three-way distinction. In addition to comes (without tense-backshifting) and came (with tense-backshifting), we find a third verb form had come in sentence (2.23). A sentence like (2.23) can be used in the situation where the speaker knows that Boris was going to come, but has just learnt that he will definitely not come. Example (2.23) therefore expresses a stronger negative commitment on the part of the speaker than example (2.22) does.

While both Comrie and Fauconnier argue that in English conditionals, different degrees of hypotheticality are expressed by the variation in the verb form, Fillmore’s (1990) study reveals that in addition to tense variation, the choice of conjunctions also affects hypotheticality. Fillmore proposes that a basic element of conditional meaning is ‘epistemic stance’, and in English conditionals, the kind of epistemic stance we take toward an utterance are marked by both our choice of conjunctions and our choice of verb forms. Fillmore defines conditionals as follows:

…those which express some sort of co-existence relation between two states of affairs, let me call them P and Q, where Q is said to hold in that alternative world (or set of alternative worlds) which is identified by the presence of P.

(Fillmore 1990:140)

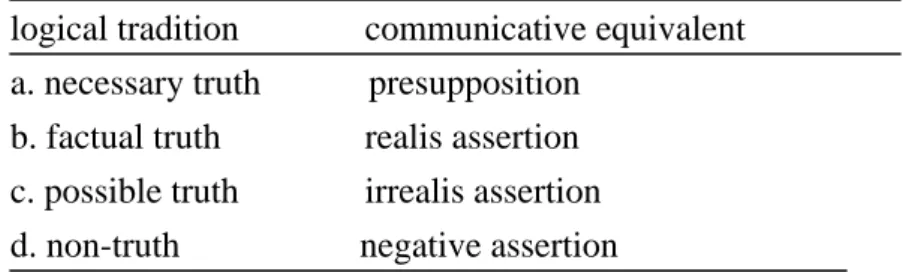

As for epistemic stance, it means the epistemic attitude which the speaker takes

toward the world represented by the conditional sentence: the speaker might regard it

as the actual world, or s/he might regard it as distinct from the actual world, or s/he

might not know whether the alternative world represented in the conditional sentence is the actual world or not. A simple matrix notion has been used to represent the speaker’s mental association with or dissociation from the world of the protasis (P):

Figure 1

(Fillmore 1990: 141)

In Figure 1, the top row represents the world in which the P expressed by the protasis is a part and the bottom row represents the world in which the P expressed by the protasis is absent. The middle row does not represent a world, but is used to indicate a state of the speech event in which the speaker does not know whether or not P holds.

In the following figures, the shaded cell indicates the speaker’s epistemic stance toward P:

Figure 2 Figure3 Figure 4

(Fillmore 1990: 143-44)

Figure 2 indicates that the speaker accepts the world of P as the actual world. Figure 3 represents a situation in which the speaker accepts as actual a world in which P does

P

-P

not hold. Figure 4 displays that the speaker does not know whether P holds or not. The following figures combined with three illustrating sentences show how different epistemic stances affect the choice of conjunctions and verb forms:

P Q P Q P Q

-P -P -P

Figure 5 Figure 6 Figure7

(2.24) When he left the door open, the dog escaped.

(2.25) If he left the door open, the dog escaped.

(2.26) If he had left the door open, the dog would have escaped.

(Fillmore 1990: 143-44)

Figures 5-7 correspond to (2.24)-(2.26) respectively. In (2.24) the speaker accepts the idea that he did indeed leave the door open and asserts that the dog escaped. In other words, the speaker expresses his/her positive stance toward P. In (2.25), the speaker does not know whether or not he left the door open and thus his/her epistemic stance here is neutral. As for (2.26), the sentence reveals the speaker’s belief that he did not leave the door open, so negative stance is involved.

Fillmore’s discussion provides us with a very important notion: tense variation

is not the only indicator for the judgment of degree of hypotheticality associated with

English conditional sentences. Going back to examples (2.24) and (2.25) provided by

Fillmore, we find that the two sentences have the same tense form, with the only

difference lying in the choice of connectors: when in (2.24) and if in (2.25). According

to Figures 5 and 6, (2.24) expresses positive epistemic stance and (2.25) expresses

neutral epistemic stance. Therefore, it can be inferred that the difference in the

epistemic stance/hypotheticality associated with the two sentences is contributed to by the two different connectors when and if. When expresses positive epistemic stance and therefore the sentence is of lower hypotheticality; if shows neutral epistemic stance and indicates higher hypotheticality.

In sum, Comrie (1986), Fauconnier (1985) and Fillmore (1990) all give elaborate explanations on the notion of ‘hypotheticality’—the speaker’s commitment to the actuality of the propositions expressed in the subordinate clauses, especially in the protases. And they all show that tense variation plays a crucial role in discriminating different degrees of hypotheticality in English conditional construction.

Furthermore, Fillmore’s study reveals that different conjunctions such as when and if can also affect hypotheticality of conditional sentences.

In fact, this semantic overlap between ‘conditional’ and ‘temporal’ clauses has been explored in many studies. It has been recognized that in many languages, conditionals interact extensively with the temporal domain. In discussing the hypotheticality of conditionals, researchers find it difficult to deal with the kind of conditional sentences in which the protasis has the meaning ‘when’ or ‘whenever’: do they fit properly into the system of hypotheticality or are they totally outside the system of conditional sentences? In the following section, we will concentrate on this issue.

2.4 Hypotheticality in Conditional and Temporal Clauses

In many languages, conditionals are reported to be closely related to the

temporal domain. For example, in languages like German and Japanese, when and if

can be of the same morphological identity; in English, when and if are sometimes

interchangeable to mark hypotheticality. Specifically, studies for different languages

show that while both conditional and temporal clauses can mark conditionality, the latter usually express lower degree of hypotheticality than the former. The difference lies in the different speaker’s attitude or epistemic stance associated with these two clauses: conditional connectors like if are usually endowed with a neutral/negative epistemic stance, and therefore they represent higher degree of hypotheticality; on the other hand, temporal connectors like when are associated with a positive epistemic stance; accordingly, they show lower degree of hypotheticality.

Reilly (1986) approaches the close relationship between conditional and temporal clauses from the point of their acquisition. He shows that when temporal and conditional clauses in English share a variety of characteristics (Reilly 1986: 312): (a) they both link simultaneous or sequential events, often implying a causal relationship;

(b) they both can occur either pre- or post-main clause; (c) in both constructions, the different semantic types are distinguished by the auxiliary verb. Furthermore, he discusses the semantic overlap and non-overlap of when and if. The highest degree of semantic overlap occurs in cases where there is a regular co-occurrence relationship between two events, for instance:

(2.27) If/When Jamie drinks cranberry juice, he gets a rash.

(Reilly 1986: 313)

(2.27) is the so-called ‘generic conditional’,

4which signals a regular co-occurrence between ‘Jamie drinking cranberry juice’ and ‘Jamie getting a rash’. When could be replaced by whenever to reflect this regular relationship. In addition, since if-clauses refer to a possible instance of such regular co-occurrence, they are also acceptable in these cases.

4 For the discussion on ‘generic conditionals’, please refer to Fillmore 1990: 152; Dancygier 1998:63-65; and Athanasiadou and Dirven 2002.

The semantic overlap decreases for conditionals which refer to future and past events, as in

(2.28) If

the strawberries are in, we’ll make fresh strawberry pie.

When (2.29) If

it rained last year in Egypt, the Nile Delta flooded.

When

(Reilly 1986:313)

There is a significant difference lying between if/when in the sentences above;

specifically, they express different degrees of expectation or certainty: when implies certainty, or at least the speaker’s expectancy of the occurrence of the event expressed in the antecedent clause, whereas if signals the speaker’s supposition of antecedent event. Therefore, in predictive when temporals like (2.28), the antecedent is expected to occur, and in past temporals like (2.29), the antecedent is in fact known to have occurred. However, for both predictive and past conditionals, the speaker is supposing the antecedent, i.e. the antecedent is only a possibility.

Reilly then summarizes that there is semantic overlap for when and if where they refer to situations occurring, having occurred, or predicted to occur, in the real world. The interchangeability of conditionals and temporal adverbs increases with the degree of certainty that a speaker has concerning the antecedent. Therefore, it appears that the more regular the co-occurrence relationship between the events in the antecedent and the consequent, the more interchangeable the when and if structures. In addition, when-clauses are restricted to refer to facts and reality, whereas if-clauses suppose the possibility of states or events in potentially real as well as irrealis situations.

Reilly’s discussion clearly shows that there is indeed semantic overlap between

conditional and temporal clauses: the interchangeability of conditionals and temporal adverbs increases with the degree of certainty a speaker has concerning the protasis.

On the other hand, the discussion also elucidates another important notion: there indeed exists some semantic difference between conditional and temporal clauses.

This difference lies in one crucial distinguishing feature: the speaker’s certainty toward the protasis event or state. When the speaker believes it to be fact, when structure is preferred; when the speaker is merely supposing the possibility of its existence, if is employed. In other words, while when expresses a positive epistemic stance, if shows a neutral/negative epistemic stance.

Akatsuka (1986) also goes deep into the notion of ‘speaker attitude’ to account for the semantic difference between conditional and temporal clauses. Discussing the identity of if and when in languages such as Japanese and German, Akatsuka asserts that if can be distinguished clearly from when as long as we take ‘speaker attitude’

into consideration: only when the speaker is uncertain about the realizability of p that we get the ‘if p’ reading in these languages; on the contrary, when the speaker explicitly commits him/herself to the factuality of p, we get the ‘when p’ reading.

Therefore, in the following example:

(2.30) Japanese:

Syuzin ga kaette ki-tara, tazune masyoo husband SBJ. returning come if/when ask will ‘If/When my husband comes home, I’ll ask’

German:

Wenn mein Mann zuruck kommt, werde ich fragen When/If my husband back come will I ask ‘If/When my husband comes home, I’ll ask’

(Akatsuka 1986: 344-45)

When the speaker is not sure whether her husband will come home or not, the sentence such as (2.30) is a conditional expression. On the contrary, when the speaker takes for granted that her husband will come home, it is a temporal expression.

By pointing out the role that ‘speaker attitude’ plays in the interpretation of conditional and temporal clauses, Akatsuka elucidates an insightful concept that conditionals and temporal clauses are in fact very different in nature: in a conditional expression, the speaker does not commit him/herself to the factuality of p, while in a temporal clause, the speaker regards p as a fact. It is this difference in ‘speaker’s attitude’ that evidently distinguishes when-reading from if-reading in the languages where when and if are of the same morphological identity.

Grundy (2000) also touches upon the issue of the semantic overlap/difference between when and if from the pragmatic point of view. He explains the semantic difference between if and when by means of the pragmatic concepts ‘presupposition’

and ‘implicature’: while temporal clauses introduced by when typically give rise to presuppositions, real conditionals introduced by if give rise to implicatures. In cases where when marks a temporal frame, the embedded when-clause provides a background against which some event is highlighted. In other words, the proposition contained in the temporal clause is identified as a presupposition, as the example When I started this book, I thought I’d never finish it (Grundy 2000:124), where the proposition I started this book is presupposed. On the contrary, conditional conjunctions such as if give rise to implicatures of possible existence in respect of the situation described in the if-clause

5. The sentence If you see her, tell her to call me

5 Grundy (2000) distinguishes two types of if-clause in terms of their status as a presupposition or an implicature. Backward-looking conditionals are counterfactual and give rise to a presupposition of non-existence in respect of the situation described in the if-clause, as in the following example: If you had sent me a Christmas card last year, I would have sent you one this year (Grundy 2000:125). The sentence presupposes that you did not send me a Christmas card last year. Forward-looking conditionals, on the other hand, give rise to implicatures of possible existence in respect of the situation described in the if-clause, like the sentence If you see her, tell her to call me back, where two implicatures are inferred: possibly you see her/possibly you do not see her.

back will give rise to the implicature possibly you see her/possibly you do not see her, and it is usually the wider context that helps the addressee to understand which of the two possibilities is the likelier.

However, temporal and conditional clauses in English do not always have such a clear-cut distinction. Like German wenn, which can have both a temporal and a conditional meaning, English when too sometimes has a conditional meaning. This is where temporal clauses and conditional clauses come to have certain degree of semantic overlap. In cases where when is used to mark a conditional meaning, the presupposition usually associated with the temporal clause would no longer hold.

When uttering the sentence When you get the chance, you should come to Durham (Grundy 2000: 130), the speaker does not seem to presuppose you will get the chance.

Similarly, in the sentence Come to Durham whenever it suits you (Grundy 2000: 130), the presupposition it ever will suit you is not obtained. These two examples suggest that the presupposition supposedly associated with temporal clauses is in fact pragmatic matter—only when the speaker is certain about the actuality of the protasis does it give rise to a presupposition; when the speaker is uncertain about the actuality of the protasis, the presupposition is not retained. In other words, in the cases where when-clauses do not trigger presuppositions, they behave as conditionals.

6Following this line of reasoning, we find that though both if-clauses and when-clauses can both mark conditionality, there exists a pivotal difference between the two clauses: while if-clauses give rise to the implicature possibly p/possibly not p, when-clauses, on the other hand, usually give rise only to the implicature (,or the so-called ‘pragmatic presupposition’) possibly p. In other words, if-clauses do express

6 Note that the term ‘presupposition’ Grundy employs in the paragraph above is ‘the presupposition in the traditional sense’, i.e. the presupposition which cannot be cancelled. It is true that when when-clauses are used to mark conditionality, they do not trigger presuppositions in the traditional sense; however, they still trigger ‘pragmatic presuppositions’. Pragmatic presuppositions behave more like implicatures in that they are cancellable.