21

0090-6905/01/0100 -0021$19.50/0 © 2001 Plenum Publishing Corporation

The Processing of Coreference for Reduced

Expressions in Discourse Integration

Chin Lung Yang,1 Peter C. Gordon,1,3 Randall Hendrick,1

Jei Tun Wu,2 and Tai Li Chou2

Three reading-time experiments in Chinese are reported that test contrasting views of how pronom-inal coreference is achieved. On the one hand, studies of reading time and eye tracking suggest that reduced expressions, such as the pronoun he, serve as critical links to integrate separate utterances into a coherent model of discourse. On the other hand, probe-word recognition studies indicate that full anaphoric expressions, such as a repeated name, are more readily interpreted than reduced expressions due to their rich lexical information, which provides effective cues to match the repre-sentation of the appropriate referent in memory. The results indicate that the ease of integrating the critical referent into a model of discourse is a function of the congruence of lexical, semantic, and discourse features conveyed by a syntactically prominent reduced expression within linguistic input. This pattern supports the view that a reduced expression is interpreted on-line and indeed plays a critical role in promoting discourse coherence by facilitating the semantic integration of separate utterances.

KEY WORDS: coreference; pronouns; discourse; Chinese.

Two contrasting views have emerged concerning the effect on the compre-hension of discourse of reduced referring expressions, such as pronouns, as compared to full referring expressions, such as proper names. According to the first view, reduced expressions are understood more readily than full expressions, while according to the second view, full expressions are

under-The research reported here was supported by a China Times Young Scholar Award to Chin Lung Yang from the China Times Cultural Foundation and by a grant from the National Science Foundation (SBR-9807028). We thank Marcus Johnson and Aaron Kaplan for their assistance in reviewing the manuscript.

1 Department of Psychology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 3270,

Davie Hall, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-3270.

2National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

stood more readily than reduced expressions. The present paper addresses these two views by providing evidence about pronoun interpretation during the reading of Chinese.

The idea that reduced expressions can be interpreted more readily than full expressions, when used appropriately, can be found in computational (Grosz, Joshi, & Weinstein, 1995), linguistic (Givon, 1992), and psycholin-guistic (Gordon, Grosz, & Gilliom, 1993) perspectives on language process-ing. According to the model proposed by Gordon and Hendrick (1998), the advantage of reduced expressions occurs because they are interpreted as refer-ring directly to salient entities in the current model of discourse, while com-plete expressions are used to introduce new entities into the discourse model that then must be equated with an entity already in the discourse model in order to achieve a coreferential interpretation. Evidence in sup-port of this view comes primarily from reading-time studies using both self-paced reading (Gordon et al., 1993; Hudson-D’Zmura, 1988) and eye tracking (Garrod, Freudenthal, & Boyle, 1994; Kennison & Gordon, 1997), but also from some probe-word tasks (Cloitre & Bever, 1988). Reading-time methods have contributed to the understanding of many language phe-nomena (Rayner & Pollatsek, 1989), but they have been criticized for only providing evidence about the time course of comprehension and not about what is being understood. With respect to the interpretation of pronouns, this raises questions about whether the faster reading times that have been observed for pronouns as compared to more referentially complete expres-sions might occur because the reader is not actually determining the refer-ence of the pronoun.

The idea that full referring expressions can be interpreted more read-ily than reduced expressions derives from the view that language compre-hension works according to general principles of human memory, where it has been clearly established that memory access improves with the degree of match between the stimulus cueing retrieval and the stimulus that gave rise to the original representation. That would be the case for establishing coreference with full as compared to reduced expressions (Greene, McKoon, & Ratcliff, 1992; Gernsbacher, 1989). Evidence in support of this view comes primarily from probe-word recognition studies where corefer-ence with a repeated name has been found to have a greater and more immediate impact on responses to probe words than do pronouns, which may not have any impact at all (Gernsbacher, 1989; Green et al., 1992). Like reading-time measures, probe-word recognition methods have been widely used but have also been criticized. Gordon, Hendrick, and Foster (2000) have argued that results in probe-word recognition studies may reflect strategies employed to keep track of likely probe words and may not reflect normal language comprehension processes. Gordon et al. (2000)

pre-sented evidence that this was specifically the case in studies using probe-word methodology to examine the coreferential interpretation of names and pronouns.

A central issue in these conflicting arguments involves the role a pro-noun plays during discourse comprehension. Two questions are of major concern: First, does the occurrence of a pronoun within linguistic input ini-tiate cognitive processes for referential resolution during the reading-time task? Indeed, the use of reading time as a measurement of the ease of estab-lishing pronominal coreference can be criticized because the time that it takes to read the pronoun and the predicate immediately following it does not nec-essarily indicate whether a coreferential interpretation of the pronoun has actually occurred. Following this view, pronouns might be read quickly because readers can postpone their interpretation until disambiguating information occurs later in the text. Second, how do the lexical features of a pronoun, particularly gender, modulate the processing of referential reso-lution? While a pronoun does not contain rich lexical information, it does contain some information which can help identify a referent.

Each of the two contrasting views outlined above is appealing in that it links a psycholinguistic issue, the comprehension of referring expressions, with other well-established domains of inquiry. Each view also generally depends on its own characteristic methodology for empirical support. Re-solving which of these views is correct, or the conditions under which each is correct, requires greater understanding of the strengths and limitations of each of the methodologies. The present experiments contribute to that under-standing by providing evidence that pronouns are interpreted under condi-tions that are similar to those that have been used in many self-paced reading and eye-tracking studies. As the experiments to be reported were performed in Chinese, we will first review aspects of the referential system of Chinese and then discuss the logic of the experiments.

Chinese has two kinds of reduced expressions, overt and zero pronouns (Li & Thompson, 1981). The zero pronoun is a nonovert, phonologically omitted expression that refers to an already-mentioned referent. Its distribu-tion is far less restricted than the zero pronouns that occur in some Euro-pean languages, like Spanish and Italian. Because it is a null form, the zero pronoun does not carry any lexical information, while the overt pronoun in Chinese, like the overt pronoun in English, can carry lexical information. In Chinese, a spoken overt pronoun is encoded only with information about number, but not with information of gender, humanness, and animacy (“Ta” means he, she, or it, while “Taman” means they). However, in written Chinese, gender varies with the visual form of overt pronouns. The variety of reduced expressions in Chinese allows referential processing to be stud-ied in cases where an overt pronoun specifies lexical information (e.g.,

gen-der) that might or might not be sufficient to identify a referent depending on the referential context. It also allows referential processing to be studied in cases of the zero pronoun, which specifies no lexical information and is therefore never sufficient to identify its referent.

Three self-paced reading-time experiments were conducted in Chinese in order to examine the nature of pronoun interpretation. The experiments used three-sentence passages, as shown in Table I.

The initial sentence introduced two named characters of different gen-ders, one in the syntactically prominent grammatical subject, Daxing ( , male), and the other in the syntactically nonprominent grammatical object,

Xiaorong ( , female). The second, critical sentence manipulated two fac-tors: One was the relationship (continue or shift) of the critical referring expression of the second sentence with its referent introduced in the first sentence. In the continue condition, the subject of the second sentence was also the subject of the initial sentence. In the shift condition, the subject of the second sentence was an object of the initial sentence, and the subject of the initial sentence was not mentioned. In this way, the pronominal subject

Table I. Sample Stimuli from Experiment 1 through Experiment 2a

Initial Sentence 1.

Daxing gaoshu Xiaorong huayuan li ying zhong sucai er bu zhong hua. “Daxing told Xiaorong that vegetables, instead of flowers, should be planted in the garden” Second (Critical) Sentence

Continue Condition 2. /∅/*

Ta/∅/*Ta renwei sucai bi hua haiyao shiyong “He/∅/*She thought vegetables are of more utility than flowers.” Shift Condition

2. /∅/∗

Ta/∅/*Ta que renwei sucai han hua dou yao zhong.

“She/∅/*He thought, however, that both vegetables and flowers should be planted.” Passage-final Sentence

3.

Huayuan de shiyong ji guihua shi henda de xuewen.

“The usage and planning of a garden are worth studying.”

aEach passage was three-sentences long. The slashes separate the forms of pronominal subject

manipulated in the second sentence. There are different kinds of combinations in terms of forms of the pronominal subject in the second sentence across experiments. Experiment 1a included a gender-disagreement/gender-agreement overt pronoun. Experiment 1b used gender-disagreement overt pronoun vs. zero pronoun. Experiment 2 used all kinds of pronouns such as gender-disagreement/gender agreement overt pronouns vs. zero pronouns.

of the second sentence was used to corefer with either the prominent entity [(Daxing ( ), continue] or the nonprominent entity [Xiaorong ( ), shift] entity in the first sentence. The second factor was the pronominal form of the grammatical subject of the second sentence. It could be a

gender-agreement overt pronoun, a gender-disgender-agreement overt pronoun, or a zero

pronoun. In the gender-agreement condition, the subject of the second sen-tence was an overt pronoun that agreed in gender with its intended referent on the first sentence. In this way, the gender feature of the subject pronoun of the second sentence would facilitate the process of discourse integration, because its gender feature identifies the appropriate referent in the discourse model. In contrast, in the gender-disagreement condition, the subject of the second sentence was an overt pronoun that did not agree in gender with the referent, which made the greatest semantic sense given how the meaning of the sentences went together. Thus, if pronouns are interpreted online the gender feature in the gender disagreement condition actually interrupts processing because its gender feature identifies an irrelevant yet gender-matched referent in the model of discourse. This would force a process of reinterpretation for the critical sentence. Finally, in the zero pronoun condi-tion, the pronominal subject of the second sentence is a null form that does not carry any kind of lexical information that could serve to help identify its referent in the discourse model.

These manipulations of gender features for the subject pronoun of the second sentence allow us to examine whether pronominal expressions within linguistic input prompt cognitive processes of referential resolution in addition to revealing the time course of the operation of these cognitive processes. It has been found that referential processing is modulated by the accessibility of the intended referent, as determined by its syntactic promi-nence, and by the lexical features of the reduced expression, such as gender (Gordon et al., 1993; Gordon & Hendrick, 1998; Yang, Gordon, Hendrick, & Wu, 1999). Yang et al. (1999) used passages as shown in Table I and found that reduced expressions (overt/zero pronouns) were preferentially used to refer to a referent introduced by a syntactically prominent expres-sion in the preceding sentence. The reading times of the second sentence were faster in the continue condition than in the shift condition. In addition, it was also found that the gender of the pronominal subject of the second sentence would promote the referential resolution for referents in the shift condition only when the overt pronoun could unambiguously indicate its referent (when there were two discourse referents of different genders in the first sentence). Under this condition, no reading-time difference was found for the second sentence between the continue and the shift conditions. Furthermore, there is some evidence from eye tracking (Ehrlich, 1983) that the occurrence of a pronoun having no antecedent that matches in gender

can disrupt comprehension. All this evidence suggests that the coreference of pronominal expressions is determined during the comprehension of a sentence based on its lexical characteristics and on the structure of the pre-ceding discourse. It is not consistent with the argument, based on probe-recognition tasks, that pronouns are weakly interpreted or not interpreted at all (Gernsbacher, 1989; Greene et al., 1992). The current work aims to add to this evidence by seeing how the congruence of lexical, semantic and dis-course features, as manipulated in the various conditions, influences reading time. These factors should have systematic effects if pronouns are interpreted during sentence comprehension, but should have no effect if they are not.

EXPERIMENTS 1a AND b

The first two experiments use self-paced reading to examine how the accessibility of referents and lexical features of a reduced expression, par-ticularly gender, influence the comprehension of a sentence in passages such as those shown in Table I. Both experiments manipulated the relationship (continue vs. shift) between the second sentence and the first sentence. The two experiments differed in terms of the kinds of referential expressions used in the second sentence. Experiment 1a used overt pronouns in two con-ditions: gender-agreement and gender-disagreement. Experiment 1b used zero pronouns and overt pronouns with gender-disagreement. This manipu-lation was used to examine the role that pronominal form plays in the pro-cessing of referential resolution where the gender feature of the pronominal subject of the second sentence can facilitate (gender-agreement), mislead (gender-disagreement), or have no effect on (zero pronoun) the identification of the appropriate referent in a model of discourse.

Method

Participants

Thirty-two participants were tested in Experiment 1a and twenty-four participants were tested in Experiment 1b. They were native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and were enrolled in Introductory Psychology at the National Taiwan University (NTU).

Stimuli

Both Experiments 1a and 1b employed a set of thirty-six three-sentence passages as shown in Table I. Across the two experiments appropriate changes were made for the second sentence of each passage in terms of the form of the pronominal subject. Four versions of each of the passages

were constructed by varying the form of the subject pronoun of the second sentence to create different kinds of discourse relationships with the first sentence. The third sentence was a general statement contextually related to the preceding two sentences that did not mention either of the two named characters. The names of the two characters in a passage were convention-ally of different genders. Only two-character Chinese names with simple strikes and visual forms, such as , , and were used to introduce named referents in experimental passages. The gender sequence for the two characters in the first sentence of each passage was counterbal-anced across passages so that half of the passages were male-female and half were female-male. The filler passages and true-false questions that fol-lowed every passage were constructed according to the guidelines described in Yang et al. (1999).

Design and Procedure

The design and procedure were very similar to that in Yang et al. (1999). Four sets of materials were constructed by assigning one of the four versions of each experimental passage to each material set. The 36 experi-mental passages in each material set were grouped with the 94 filler pas-sages to create five experimental blocks of 26 paspas-sages, which were preceded by an initial practice block consisting of 16 filler passages. The initial practice block served to familiarize participants with the reading task. Passages were presented one sentence at a time and participants were instructed to read each sentence at a natural pace. They pressed the space bar in order to advance to the next sentence.

Results

Experiment 1a

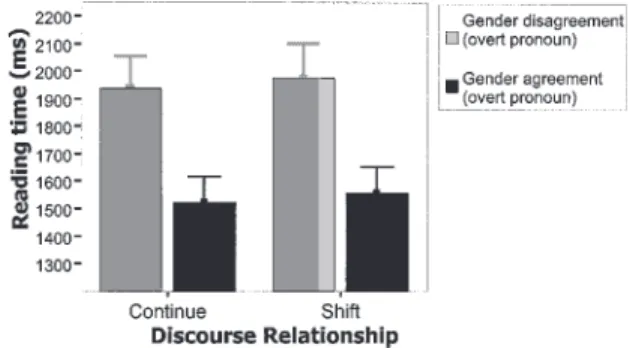

Figure 1 indicates the mean reading time for the critical sentence as a function of the experimental manipulations. Gordon et al.’s criterion (1993, p.326) in terms of premature or careless responses of reading times of the second sentence was adopted to exclude outliers from data analysis. Outliers constituted 2.4% of the data. This criterion is employed for the remaining experiments reported in this study.

Analysis of variance was conducted on the reading times of the critical sentences both by participants (F1) and by items (F2) to test the generality

of the results. The reading times of sentences with gender-disagreement overt pronoun induced significant slower reading time than those with gender-agreement overt pronouns, both by participants [F1(1, 31) =40.28,

signif-icant difference of reading times between continue and shift conditions either by participants [F1(1, 31) =0.56, p=.46) or by items [F2(1, 35) =0.40,

p=.53]. The interaction effect was significant neither by participants [F1(1, 31)

=.00, p = .987] nor by items [F2(1, 35) =.00, p =.978]. The mean

accu-racy for comprehension questions was 93.1% overall, ranging from 92.6% in the gender-disagreement-shift condition to 94.3% in the gender-agreement-continue condition.4Statistical analysis showed that no significant effects on

accuracy were observed for the experimental conditions.

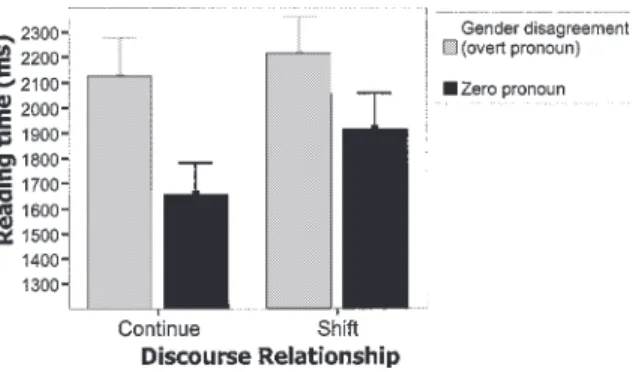

Experiment 1b

Figure 2 shows the mean reading times for the critical sentence as a function of the experimental conditions. Outliers excluded from the reading-time analysis constituted 2.8% of the data. The gender-disagreement overt pronoun acted the same way as in Experiment 1a. It induced slower read-ing time than did a zero pronoun both by participants [F1(1, 23) =34.63,

p<.001) and by items [F2(1, 35) =38.9, p<.001]. The main effect of

dis-course relationship was significant. The reading times of sentences in the continue condition were significantly faster than in the shift condition both

Fig. 1. Mean reading times (milliseconds) of the critical sen-tences that include experimental manipulations. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval of mean.

4In addition, the analysis of reading times of the passage-final sentence demonstrated a strong

spillover effect, where passage-final sentences in the gender-disagreement overt pronoun condition were read significantly slower than passage-final sentences in the gender-agreement overt pronoun condition. This spillover effect was only induced by the gender-agreement manipulation and has not been observed in our previous work (Yang et al., 1999) that did not manipulate gender-agreement. The spillover effect, due to gender-disagreement, was also observed in the other experiments reported in this paper. It is consistent with the effects observed in the critical sentences, which are the focus of our discussion.

by participants [F1(1, 23) =7.69, p <.05) and by items [F2(1, 35) =6.11,

p<.05]. An interaction effect was observed neither by participant [F1(1, 23)

=1.41, p =.25] nor by items [F2(1, 35) = 1.47, p=.234]. A posthoc

con-trast for sentences including a zero pronoun indicated that, consistent with previous studies (Yang et al., 1999; Experiments 3 and 4), the shift condi-tion induced significantly slower reading time than the continue condicondi-tion both by participants [t1(1, 23) = 2.66, p < .05] and by items [t2(1, 35) =

2.67, p<.05).

In addition, the mean accuracy for comprehension questions was 91.3% overall, ranging from 95.4% in the zero-pronoun-continue condition to 88.3% in the zero-pronoun-shift condition. Statistical analysis showed that there was a significant interaction between the forms of pronominal subject and discourse relationship for the accuracy of comprehension ques-tions [F(1, 23) =9.89, p<.01]. These patterns suggest that the difficulty of integrating the critical sentence into the model of discourse when the overt pronoun induced gender-disagreement spread over to the comprehension question.

Discussion

The results show that the reading times of the second sentence are a function of the form of the pronominal subject in the second sentence. Consistent with what we found previously (Yang et al., 1999; Experiment 4), when the pronominal subject is an overt pronoun with gender-agreement, the critical sentence in the shift condition is read as fast as in the continue con-dition. Further, when the pronominal subject is a zero pronoun, the critical

Fig. 2. Mean reading times (milliseconds) of the critical sentences as a function of the experimental manipulations. Error bars show 95% confidence interval of mean.

sentence in the continue condition is read faster than that in the shift con-dition. This pattern indicates that the comprehension of reduced expressions is modulated by the accessibility of referents in the model of discourse, as determined by the degrees of syntactic prominence of the expressions that introduced the referent in the preceding sentence. However, when a reduced expression’s gender feature can unambiguously pick out its intended refer-ent in the model of discourse, its gender feature facilitates the processing of referential resolution for referent in the shift condition, because its gen-der feature can pick out its intended referent directly from a model of dis-course.

Furthermore, in both Experiments 1a and 1b, when the critical sen-tence had an overt pronoun that induced gender-disagreement, participants had great difficulty integrating the sentence into the discourse model, as shown by the fact that the reading times of the second sentences with a gender-disagreement overt pronoun were much slower than the reading times of the second sentences with a gender-agreement overt pronoun (by 424 msec, Experiment 1a). This indicates that when a sentence has a gram-matical subject whose gender cue is inconsistent with its intended referent, this lexical information in the pronoun disrupts the process of integrating the semantics of the following predicate with the semantics of an irrelevant referent in the model of discourse. This inconsistency of semantic integra-tion forces participants to reinterpret the critical sentence and thus results in much slower reading time. This pattern shows that readers do, in fact, assign coreferential interpretations to the pronouns, a finding that is not consistent with the claim, based on probe-word recognition studies, that pronouns are not readily interpreted in normal reading (Greene et al., 1992).

EXPERIMENT 2

Comparison of the results of Experiments 1a and 1b provides a between-participant view of how different forms of referring expressions affect the comprehension of a sentence in different discourse contexts. The current experiment uses a within-participant design to look at this question. The use of this design allows us to directly compare the processing of sentences with overt pronouns that have either gender agreement or gender disagree-ment with zero pronouns that do not provide gender information. The design also allows us to examine the generality of the findings across vari-ations in the composition of types of trials that might induce different read-ing strategies. In particular, sentences with pronouns that induce gender disagreement are semantically anomalous. Using a within-participant design

reduces the proportion of such sentences in the stimulus materials. Thus, this experiment can add additional generality to the evidence from Experi-ments 1a and 1b concerning the processing of referential resolution for reduced expressions.

Method

Participants

Thirty-six new undergraduate participants from the same population of the previous experiments participated in this experiment.

Stimuli, Design, and Procedure

The same set of thirty-six experimental passages from Experiment 1a and 1b was employed in this experiment. Appropriate changes were made for the critical sentence of each passage as specified above. The experi-mental design and procedure were the same as in previous experiments.

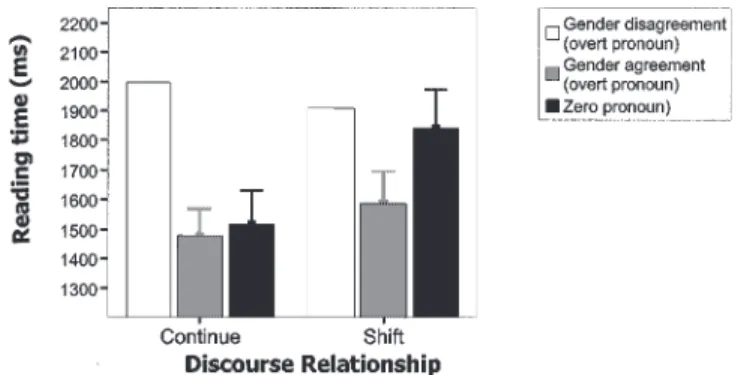

Results

Figure 3 indicates the mean reading time for the critical sentence as a function of the experimental manipulations. Outliers excluded from the reading-time analysis constituted 3.4% of the data. The main effect of dis-course relationship reached statistical significance both by participants [F1(1, 35) = 9.57, p< .01) and by items [F2(1, 35) = 4.85, p <.05]. The

Fig. 3. Mean reading times (milliseconds) of the critical sentences as a function of the experimental manipulations. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval of mean.

main effect of the forms of pronominal subjects was significant both by participants [F1(2, 70) =34.87, p< .001] and by items [F2(2, 70) = 29.22,

p< .001]. A significant interaction effect between continue/shift and form of pronominal subjects was also found by participants [F1(2, 70) = 5.43,

p< .01] and by items [F2(2, 70) =6.19, p<.01]. Planned contrasts on the

difference between reading times of critical sentences in the continue/shift conditions for different forms of pronominal subjects indicated significant differences for zero pronouns [t1(35) =3.75, p<.001; t2(35) =4.07, p<.001],

but for neither gender-agreement overt pronouns [t1(35) = 1.25, p = .10;

t2(35) =1.36, p=.10] nor gender-disagreement overt pronouns [t1(35) =1.04,

p = .30; t2 (35) = 1.13, p = .20]. The mean accuracy for comprehension

questions was 92.2% overall, ranging from 95.3% in the zero-pronoun-continue condition to 89.2% in the gender-disagreement-shift condition. Accuracy was not influenced significantly by experimental conditions.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 replicated not only the reading-time pat-terns of Experiments 1a and 1b, but also what has been found in previous studies (Yang et al., 1999), where no passages contained overt pronouns that induced gender-disagreement. When the two referents introduced in the initial sentence had differential syntactic prominence and different genders, the reading time difference between the continue and the shift conditions was observed only when the passages contained a zero pronoun as the gram-matical subject of the second sentence. The reading times of the critical sen-tences in the continue condition were faster than those in the shift condition. In contrast, for sentences containing gender-agreement overt pronouns, the reading times of the critical sentences in the shift condition were as fast as those in the continue condition because the gender feature of the pronoun facilitated the identification of the suitable referent. In addition, for sen-tences containing overt pronouns that induce gender disagreement, partici-pants had great difficulty integrating the sentences with the semantics of the model of discourse. These results are consistent with, and add generality to, the results of Experiments 1a and 1b.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The goal of the experimental research reported here is to examine the comprehension of reduced expressions in discourse. Addressing this issue pro-vides an opportunity to advance our understanding not only of the nature of the cognitive processes used in pronominal coreference, but also of the

strengths and limitations of two kinds of methodological tools that give very disparate views of the manner in which referential resolution is achieved. The results suggest that a reduced expression is interpreted on-line as part of sentence comprehension in a way that is strongly influenced by the quite minimal lexical information conveyed by the reduced expression. These results do not support the view derived from probe-word recognition studies that a pronoun does not function as a critical link to a referent in a discourse model, due to its spare lexical cues (Gernsbacher, 1989; Greene et al., 1992). Rather, they support the contrasting view that has been estab-lished from reading time and eye-tracking studies that a reduced expression is a natural vehicle for coreference, because it serves to directly link its associated predicate with semantic information in the current discourse model.

Our view is that unreduced, full expressions (e.g., proper names like

John or Mary or definite descriptions like the table) are initially interpreted

in relation to general knowledge and then can serve the discourse function of introducing a new discourse entity into the universe of a discourse. In contrast a reduced expression is used as a link to the referential semantics in a model of discourse and thus is interpreted as referring to discourse ref-erents that are already represented in a discourse model. This critical con-trast between nominal and pronominal coreference is further elaborated in the Gordon and Hendrick (1998) model. The model formalizes rules that interpret the ways in which the syntactic and sequential structure of a lan-guage shapes the processing of reference and coreference.

According to this model, pronominal expressions are natural vehicles for coreference because they refer directly to the associated semantics of referents that are represented in the model. This is done by a structure-based cognitive process that searches for the suitable antecedent, one that matches grammatically encoded features, such as number, gender, etc., directly from the existing model of discourse in a prominence order, from the most to least prominent referent. In contrast, the nominal expressions corefer with their intended referents in an indirect way and thus require more laborious processes to establish coreference in a discourse. Furthermore, this model conjectures that the structural organization of a language is a primary deter-minant of the prominence of discourse entities within a discourse segment. High prominence of a discourse entity promotes the integration of subse-quent utterances into a model of discourse by facilitating coreference between the suitable antecedent and pronominal expression. In previous studies (Yang et al., 1999) and in the current work, the results supported this notion by showing that the ease of integrating the critical referent into a discourse model is a function of the syntactic prominence of discourse entities introduced in the first sentence, as demonstrated by the effects of

the continue/shift manipulation. These patterns were also consistent with similar studies in English (Gordon et al., 1993).

This conclusion is given striking confirmation by a related study we have conducted of pronominal coreference in Chinese (Yang, Gordon, Hendrick, & Hue, 2000). We have found that direct objects can be given increased prominence either by promotion to subject position (as in the bei construction) or by being positioned between the subject and verb (as in the

ba construction). This increased prominence of the object results in

signifi-cant increases in speed of reading times in our shift manipulations. The ba construction has special significance because the increased prominence of the direct object is achieved without changing the semantics or the gram-matical relations of the utterance when compared to paraphrases in the canonical subject-verb-object ordering of most Chinese sentences. Much of the previous work on prominence (see Gordon & Hendrick, 1998, for a review) has attempted to define the notion in terms of grammatical rela-tions. Some researchers have tied prominence to a hierarchy of grammati-cal relations in which subject outranks direct object, which, in turn, outranks other grammatical relations such as indirect object. Other researchers have attempted to define prominence in terms of matching grammatical relations. However, in Gordon and Hendrick (1997, 1998) it is conjectured that the structural organization of an utterance is able to deter-mine the relative prodeter-minence of NPs. In a great many constructions these disparate formulations of prominence converge empirically. The Chinese ba construction provides us with a good empirical test of the different concep-tualizations of prominence. This test seems to favor the structural definition of prominence. Reading times become faster in the shift condition using the

ba construction, even though the direct object has changed only its

struc-tural position and not its grammatical relation to the predicate.

Thus, pronominals have been demonstrated to be a primary contributor to discourse coherence because they present a link within a discourse seg-ment chain of referents or propositions that are built increseg-mentally in a model of discourse. This process of comprehension starts relatively quickly upon occurrence of the pronoun and, in turn, triggers the subsequent seman-tic integration between its predicate and the model of discourse being con-structed. Such a process of referential resolution is modulated by the syntactic prominence of discourse entities and the lexical features of a pronominal anaphor.

REFERENCES

Cloitre, M., & Bever, T. G. (1988). Linguistic anaphors, levels of representation, and dis-course. Language and cognitive processes, 3, 293–322.

Enrlich, K. (1983). Eye movements in pronoun assignment: A study of sentence integration. In K. Rayner (Ed.), Eye movements in reading: Perceptual and language processes. News York: Academic Press.

Garrod, S., Freudenthal, D., & Boyle, E. A. (1994). The role of different types of anaphors in the on-line resolution of sentences in a discourse. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 39– 68. Gernsbacher, M. A. (1989). Mechanisms that improve referential access. Cognition, 32, 99–156. Givon, T. (1992). The grammar of referential coherence as mental processing instructions.

Linguistics, 30, 5–55.

Gordon, P. C., Grosz, B. J., and Gilliom, L. A. (1993). Pronouns, names, and the centering of attention in discourse. Cognitive Science, 17, 311–347.

Gordon, P. C., and Hendrick, R. (1997). Intuitive knowledge of linguistic co-reference. Cognition, 62, 325–370.

Gordon, P. C., and Hendrick, R. (1998). The representation and processing of co-reference in discourse. Cognitive Science, 22, 389 – 424.

Gordon, P. C., Hendrick, R., & Foster, K. (2000). Language comprehension and probe-list mem-ory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 26, 766–775. Greene, S. B., McKoon, G., & Ratcliff, R. (1992). Pronoun resolution and discourse models.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 266–283. Grosz, B. J., Joshi, A. K., & Weinstein, S. (1995). Centering: A framework for modelling the

local coherence of discourse, Computational Linguistics, 21, 203–226.

Hudson-D’Zmura, S. B. (1988). The structure of discourse and anaphore resolution: The dis-course center and the roles of noun and pronouns. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester.

Kennison, S. M., & Gordon, P. C. (1997). Comprehending referential expressions during read-ing: Evidence from eye tracking. Discourse Processes, 24, 229–252.

Li, C. N., & Thompson, S. A. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. Berkeley, California, University of California Press.

Rayner, K., & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Yang, C.-L., Gordon, P. C., Hendrick, R., & Wu, J. T. (1999). Comprehension of referring expressions in Chinese. Language and Cognitive Processes, 14, 715–743.

Yang, C.-L., Gordon, P. C., Hendrick, R., & Hue, C. W. (2000, March). The processing of coreference for reduced expressions in discourse integration—A case study of Chinese. Paper presented at the 13th Annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing, La Jolla, California.