pp.183-216, No. 16, Jun. 2008

College of Humanities and Social Sciences Feng Chia University

Exploring the Reflection of Teachers’

Beliefs about Reading Theories and

Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

Yu-Chen Chou

∗Abstract

The current study based on the assumption that teachers are highly influenced by their beliefs, which in turn impact the ways they plan their lessons, the kinds of decision they make, and the methods they apply in their classrooms. The present study aims, first, to investigate the construct of teachers’ belief systems about reading theories and strategies among university instructors, then to explore the degree of discrepancies or consistencies between teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and strategies and their practical teaching activities in the EFL setting of Taiwan. The questionnaire adapted Likert scales, containing three parts--the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and actual employment of reading theories and strategies in classrooms. Forty-two English instructors from two universities in central Taiwan participated in the current study. The results have shown that the instructors emphasized linguistic knowledge, cognitive strategy and metacognitive strategy. The data also provided strong evidence that reading theories and strategies in the three domains–the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and actual employment of reading theories and strategies in practical classrooms, were positively correlated with each other.

Keywords: teachers’ beliefs, teacher training, reading strategies, EFL reading in Taiwan

∗

I. Introduction

There has been a great amount of literature indicating that teachers’ belief systems have a significant impact on their perceptions and judgments that in turn affect their classroom practices. (i.e., Nespor, 1987; Weinstein, 1989; Pajares, 1992;

Williams & Burden, 1997, Farrell, 2005).1 Teachers’ beliefs are closely related to

their values, views of learners, attitudes toward learning, and conceptions of teachers’ roles in teaching practices. Therefore, the information and knowledge about teachers’ belief systems are extremely important in terms of improving both

professional preparation and teaching effectiveness (Nespor, 1987).2

However, a good deal of discussion of the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teachers’ practices has centered on the primary and secondary teacher education. Little attention has been paid at the higher education level (Kane, Sandretto & Heath,

2002).3 Regardless of the importance of understanding teachers’ beliefs, little

research has focused on foreign language reading in higher education in Taiwan. Reading research has been one of the most crucial areas in the studying of second

language acquisition (e.g. Bernhardt, 1991; Swaffar & Bacon, 1993).4 Many

researchers (i.e., Anderson, 1999)5 have claimed that reading plays important roles

in learning second/foreign language. According to Anderson (1999),6 reading is “an

essential skill for English as a second/foreign language…and the most important

1

Nespor, J. “The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching,” Journal of Curriculum Studies, No.19, (1987), pp.317-328. Weinstein, C.S. “Teacher Education Students’ Perceptions of Teaching,” Journal of Teacher Education, Vol.40, No.2 (1989), pp.53-60. Pajares, M.F. “Teachers Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct,” Review of Educational Research, Vol.62, No.3 (1992), pp.307-332. Williams, M. & Burden, R.L. Psychology for Language Teachers: A Social Constructivist Approach, (UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997). Farrell, T.S.C. “Grammar Teaching: A Case Study of Teachers' Beliefs and Classroom Practices,” TESL-EJ, (September 2005).

2

Nespor, J., op cit, pp. 317-328.

3

Kane, R., Sandretto, S. & Heath, C. “Telling Half the Story: A Critical Review of Research on the Teaching Beliefs and Practices of University Academics,” Review of Educational Research, Vol.72, No.2 (2002), pp.177-288.

4

Bernhardt, E. B. Reading Development in a Second Language: Theoretical, Empirical, and Classroom Perspectives. (Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1991). Swaffar, J. K. & Bacon, S. “Reading and Listening Comprehension: Perspectives on Research and Implications for Practice,” in Hadley, A.O. (Ed.), Research in Language Learning (Lincolnwood: National Textbook Company, 1993), pp.124-155.

5

Anderson, N. Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies, (Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999).

6

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

skill to master. With strengthened reading skills, ESL/EFL readers will make important progress and attain greater development in all academic areas” (p.2).

In the EFL setting of Taiwan, reading is extremely important in higher education because Taiwanese college students are expected to read textbooks for different subjects written in English. In order to help them access professional knowledge and skills in either academic or career pursuit, reading instruction on the college level has become a key factor in cultivating students’ achievement. Based on this concern, the current study is also motivated by the claim by Kane, Sandretto &

Heath (2002),7 “an understanding of university teaching is incomplete without a

consideration of teachers’ beliefs about teaching and a systematic examination of the relationship between those beliefs and teachers’ practices” (p.181). Therefore, the present study aims, first, to investigate the construct of teachers’ belief systems about reading theories and strategies among university instructors, then to explore the degree of discrepancies or consistencies between teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and their practical teaching activities.

In order to address these needs, this study is organized around the following research questions: (1) What is the construct of teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and strategies among university instructors? (2) What relationship exists between their beliefs about reading theories and strategies and their practices? (3) Is there any significant difference in teachers’ belief systems among teachers of different nationalities? And (4) Is there any significant difference in teachers’ belief systems between female and male teachers?

II. Review of Literature

Theories of teachers’ beliefs and second language reading provide rudimentary underpinnings that are employed by the current study. The review of literature section includes theories of teachers’ belief systems and reading theories that contribute to designing research procedure and interpreting the results of the study.

A. Theories of Teachers’ Belief Systems

Researchers (i.e., Sigel, 1895; Harvey, 1986)8 have worked on providing a

precise definition of teachers’ beliefs or belief systems. For example, Sigel (1895)9

7

Kane, R., Sandretto, S. & Heath, C., op cit.

8

Sigel, I.E., “A Conceptual Analysis of Beliefs,” in Sigel, I.E. (Ed.), Parental Belief Systems: the Psychological Consequences for Children, (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1985), pp.345-371. Harvey, O.J.

defines beliefs as “mental constructions of experience-often condensed and

integrated into schemata or concepts” (p.351), and Harvey (1986)10 as “an

individual’s representation of reality that has enough validity, truth, or credibility to guide thought and behavior” (cited by Pajares, 1992, p.313).

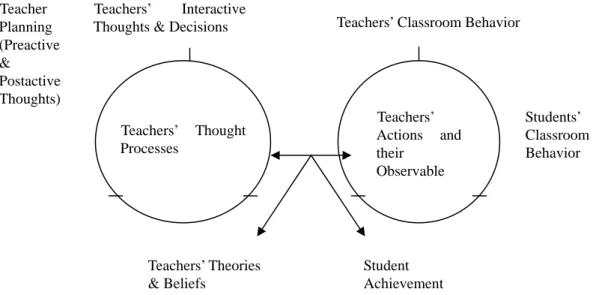

Among a plethora of research related to teachers’ belief system, Clark &

Peterson (1986)11 construct a model of teacher thought and action that visualizes the

processes of teachers’ thinking and observable behavior in classrooms (see Figure 1). The model points out two domains: a) teachers’ thought processes, and b) teachers’ actions and their observable effects that are important in the process of teaching. The former domain includes three unobservable elements, such as teachers’ planning, teachers’ interactive thoughts and decisions, and teachers’ theories and beliefs. In contrast, the latter domain covers elements, such as teachers’ classroom behavior, students’ classroom behavior, and student achievement which are in turn observable. A double-headed arrow placed between these two domains indicates that there is a reciprocal relationship between teachers’ thought and action. Clark & Peterson

(1986)12 explain that “teachers’ actions are in a large part caused by teachers’

thought processes, which then in turn affect teachers’ actions” (p.258).

While these two domains influence each other and shape the different types of behavior teachers display in their practices, other constraints or opportunities (i.e., physical setting, class size, or external influence from schools) also make an impact on the processes of teachers’ thought and action.

“Belief Systems and Attitudes Toward the Death Penalty and Other Punishments,” Journal of Psychology, No.54 (1986), pp.143-159.

9

Sigel, I.E., op cit.

10

Harvey, O.J., “Belief Systems and Attitudes Toward the Death Penalty and Other Punishments,” Journal of Psychology, No.54 (1986), pp.143-159.

11

Clark, C.M., & Peterson, P.L. “Teachers’ Thought Processes,” in Wittrock, M.C. (Ed.), Hand book of research on teaching, (NY: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1986), pp.255-296

12

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

Figure 1: A model of teacher thought and action (Clark & Peterson, 1986, p.257)

Pajares (1992)13 further distinguishes belief and knowledge and claims that

“belief is based on evaluation and judgment; knowledge is based on objective fact”

(p. 313). For Nespor (1987),14 an affective nature can be found in belief systems; in

contrast, knowledge systems are grounded within a cognitive nature.

A review of the extant literature reveals that a great number of teachers’ beliefs studies reflect mixed results in which both a confirmed and a disconfirmed relationship exists between teachers’ theoretical orientation and their teaching

practice. For example, Hoffman and Kugle (1981)15 conducted a qualitative study to

assess the relationship between elementary teachers’ beliefs and the use of verbal feedback for instructional purposes. The findings showed that there was a significant variation between teachers’ reported beliefs about guided oral reading and feedback given to their students.

Davis and Wilson (1999)16 conducted a case study to examine the congruity

between a Title 1 teacher’s reader-based beliefs and her instructional practices. The

13

Pajares, M.F., “Teachers Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct,” Review of Educational Research, Vol.62, No.3 (1992), pp.307-332.

14

Nespor, J., op cit, pp.317-328.

15

Hoffman, J.V. & Kugle, C., “A Study of Theoretical Orientation to Reading and Its Relationship to Teacher Verbal Feedback During Reading Instruction,” Journal of Classroom Interaction, No.18 (1981), pp.2-7.

16

Davis, M.M. & Wilson, E.K., “A Title 1 Teacher’s Beliefs, Decision-making, and Instruction at the Third and Seventh Grade Levels,” Reading Research and Instruction, Vol.38, No.4 (1999),

Teachers’ Thought Processes Teachers’ Actions and their Observable Student Achievement Teachers’ Theories & Beliefs Teachers’ Interactive

Thoughts & Decisions Teachers’ Classroom Behavior

Students’ Classroom Behavior Teacher Planning (Preactive & Postactive Thoughts)

results showed that the degree of consistency varied across two school setting-the teacher taught at the third grade and later at the seventh grade. However, a positive relationship existed between her beliefs about reading and instructional decision-making in both settings.

Focusing on 176 bilingual teachers who taught at pre-kindergarten through 5th

grade level, Flores (2001)17 conducted an exploratory survey study which

investigated teachers’ beliefs about the nature of knowledge and how these beliefs influenced self-reported practices. The results have indicated that bilingual teachers have specific beliefs about how bilingual children learn. For example, these teachers believed that “knowledge is primarily constructed through interactive experiences in the native language,” or “conceptual knowledge will be transferred from the first language to the second language” (p.256). Also, bilingual teachers’ beliefs are influenced by their prior experiences, in particular, professional teaching. The study is significant in providing insight into bilingual teacher preparation programs.

Woolacott (2002)18 conducted a series of interviews to identify teachers’

beliefs and strategies about reading instruction among two experienced 7th grade

teachers. The results highlighted the importance of teachers’ beliefs that in turn had a strong impact on the choice of teaching approaches. The findings have contributed to the application of teaching practices and understanding teachers’ decision making.

As to foreign language reading, Johnson (1992)19 examined 30 ESL teachers’

theoretical beliefs about second language learning and teaching and their classroom practices during literacy instruction. Focusing on the methodological divisions of skill-based, rule-based and function-based approaches, she found that “…the majority of these ESL teachers (60%) possess clearly defined theoretical beliefs which consistently reflect one particular methodological approach to second

language teaching” (cited by Borg, 2003, p.102).20 Interestingly, the study found

that the years of teaching experience also play a significant role in teachers’ belief construct. Less experienced teachers seem to favor a functional approach and more

pp.290-299.

17

Flores, B.B., “Bilingual Education Teachers’ Beliefs and Their Relation to Self-reported Practices,” Bilingual Research Journal, Vol.25, No.3 (2001), pp.251-275.

18

Woolacott, T., “Teaching Reading in the Upper Primary School: a Comparison of Two Teachers’ Approaches,” (Brisbane, Australia: Annual conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, December, 2002).

19

Johnson, K.E., “The Relationship between Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices During Literacy Instruction for Non-native Speakers of English,” Journal of Reading Behavior, Vol.24, No.3 (1992), pp.83-108.

20

Borg, S., “Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching: A Review of Research on What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe, and Do,” Language Teaching, 36 (2003), pp.81-109.

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

experienced teachers tend to adopt a skill-based approach. The result has implied that the methodological approaches that were prominent when these ESL teachers began teaching may have significantly influenced their theoretical beliefs.

Collie Garden (1996)21 conducted a qualitative study to investigate the

consistency between teachers’ beliefs and practices in foreign language reading instruction. Six secondary teachers of French and Spanish in the USA served as informants in her study. She found generally a consistent relationship between teachers’ reported beliefs and their observed practices in reading instruction. Exceptions included beliefs such as students need frequency opportunities to read, the use of L1 should be minimized during reading instruction, and reading aloud interferes with comprehension. A further investigation led to the conclusion that the discrepancy might result from “the day-to-day necessity of planning activities for students who did not or could not perform according to the teachers’ expectations” (p.390).

B. Reading Theories

According to Kamil (1986),22 it is an accepted practice that the terms model

and theory are used interchangeably in much of the educational literature. However, he further defines that theories refer to “abstract systems for making predictions that can be confirmed or disconfirmed by later experimentation,” (p.71) while models are, on the other hand, “concrete constructions used to represent, infer, interpret and visualize the elements in an area of interest” (pp.71-72). The current study applies a broad view of reading theories regarding their instructional implications and accessibility to teachers. Reading theories include areas such as prominent reading models, teaching approaches and reading strategies.

Research into developing theories of second language reading process has been

productive for the past two decades (Everson & Ke, 1997)23. Kamil (1986)24

reviews first language models which to varying degrees influence how the second

21

Collie Garden, E., “How Language Teachers’ Beliefs about Reading are Mediated by Their Beliefs about Students,” Foreign Language Annals, Vol.29, No.3 (1996), pp.387-95.

22

Kamil, M.L., “Reading in the Native Language,” in Wing, B.H. (Ed.), Listening, Reading, and Writing: Analysis and Application, (Middlebury, VT; Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986), pp.71-91.

23

Everson, M. E. & Ke, C., “An Inquiry into the Reading Strategies of Intermediate and Advanced Learners of Chinese as a Foreign Language,” Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association, No.32 (1997), pp.1-20.

24

Kamil, M.L., “Reading in the Native Language,” in Wing, B.H. (Ed.), Listening, Reading, and Writing: Analysis and Application, (Middlebury, VT; Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986), pp.71-91

language reading process is conceptualized. He claims that there have been three general orientations of reading models: bottom-up models (text-based, or skills models), top-down models (reader-based or holistic models), and interactive models (balanced models).

The bottom-up model is based on the assumption that “the reader begins the reading process by analyzing the text in small units,” and “these units are built into

progressively larger units until meaning can be extracted” (Kamil, 1986, p.73).25 As

a result, the meaning of any text must be decoded by readers’ processing incoming data in which grammatical skills, vocabulary development and syntax structures are highly emphasized.

In contrast, in top-down processing, readers construct meaning by using general knowledge of the world or of particular text components to predict what comes next

in the text. Researchers (i.e., Goodman, 1976)26 postulate that reading processes are

initiated by making guesses about the meaning of the text. As the ongoing decoding process continues, readers decode the text to either verify or modify their guesses.

For Goodman (1976),27 the reading process is a psycholinguist guessing game in

which readers rely more on the structure and meaning of language rather than on the graphic information from text.

Interactive models disconfirm the linear order of reading processes from the previous two models. This classification is an integration of both the bottom-up and

the top-down models. For example, Rumelhart (1977),28 influenced by schema

theory, believes that “the various stages of processing can interact with each other,

mutually facilitating the interpretation of the text” (Kamil, 1986, p.78)29.

In the field of second language reading, Bernhardt (1986)30 identified two

prominent models for second language reading: Coady’s (1979)31 psycholinguistic

models of an ESL reader and Bernhardt’s (1986) constructivist model. These two

25

Kamil, M.L., op cit.

26

Goodman, K.S., “Reading: a Psycholinguistic Guessing Game,” in Singer H. & Ruddell, R.B. (Eds.), Theoretical Models and process of Reading, (Newark, DE: International Reading Association, 1976), pp.497-450

27

Goodman, K.S., op cit.

28

Rumelhart, D.E., “Toward an Interactive Model of Reading,” in Dornic, S. (Ed.), Attention and performance VI, (pp.573-603). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1977.

29

Kamil, M.L., op cit., pp.71-91.

30

Bernhardt, E. B., “Reading in the Foreign Language,” in B. H. Wing (ed.), Listening, Reading, and Writing: Analysis and Application, (Middlebury, VT: Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986), pp.93-115.

31

Coady, J. A., “Psycholinguistic Model of the ESL Reader,” in Mackay, R.; Barkman, B. & Jordan R.R. (Eds.), Reading in a Second Language, (Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1979).

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

models have covered a comprehensive range of components. Coady’s (1979)32

model consists of three interacting features: conceptual abilities, background knowledge and process strategies. The conceptual ability refers to intellectual capacity that is not easily achievable in either first or second language instruction. In other words, if readers cannot understand the concepts presented in the reading passage, reading tasks are impossible to accomplish. Second, background knowledge plays an extremely important role in reading comprehension. When learners perform reading tasks, they activate existing schemata that assist in successful comprehension. Finally, process strategies refer to mental subroutines available to the learners. These strategies include factors such as grapheme-morphophoneme correspondences, syllable-morpheme information, syntactic information, lexical and contextual meaning, cognitive strategies, and affective mobilizers (p.7). Referring to the use of the process strategies, as readers increase proficiency they become masters of building, evaluating, and reacting to the textual message rather than translating the text and solving word and vocabulary problems. In other words, advanced learners do more inferencing and less literal decoding than beginning learners.

Through a synthesis of the extant first language reading models, Bernhardt

(1986)33 developed a constructivist model for foreign language reading. The model

emphasizes that reading is an active process of constructing meaning in which the reader incorporates textual information to his existent system of knowledge. It involves both text-driven and conceptually-driven factors. The former includes components, such as word recognition that refers to the assignment of meaning to words either through ‘translation or inference; phonemic/graphemic decoding that is about the proper match of the spoken language with its graphic equivalents, and syntactic feature recognition that refers to correctly establishing the relationship of words within sentences. The latter, conceptually-driven process covers factors such as intratextual perceptions that refer to how different parts of the text are integrated into a coherent discourse structure, prior knowledge about the application of word knowledge that facilitates or hinders textual comprehension, and metacognition that refers to the reader’s reflection and monitoring of how well the message seems to be constructed.

32

Coady, J. A., op cit.

33

Anderson (1999)34 suggests a psycholinguistic approach to the theory of reading in which reading is an active process that involves readers’ knowledge, skills and experiences. Such factors are activated to construct meanings in the text. Based on the philosophy for teaching developed through research and practices, Anderson explores certain elements of reading instruction which are represented with the ACTIVE teaching strategies. The ACTIVE framework consists of eight elements such as active background knowledge, cultivate vocabulary, teach for comprehension, increase reading rate, verify reading strategies, evaluate progress, build motivation, and selection appropriate reading materials. These elements have been viewed as the theoretical underpinnings of the teaching strategy and their importance in reading programs for second langue learners have been identified

(McPherson, 2003).35

The literature reviewed here has provided related information that is important to guide the current study. For example, the classic model of teacher thought and

action provided by Clark and Peterson (1986)36 has served as a fundamental

principle for the current study. However, the little amount of studies on investigating teachers’ beliefs in the area of L2 reading instruction have indicated an unclear picture of teachers’ belief construct in teaching reading. Therefore, research on L2 teachers’ beliefs on their practices is required to contribute to this unclear area.

III. Research Method

A. Participants

The informants in the current study consist of 42 English instructors teaching in English programs at two universities in central Taiwan with the ratio of male to female 29% to 71%. Table 1 summarizes their demographic information.

Table 1: Demographic Information of Participants

Category Level N %

Gender Male 12 29

Female 30 71

34

Anderson, N., Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies, (Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999).

35

McPherson, P., “Review of Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies,” Reading in a Foreign Language, Vol.15, No.1 (2003).

36

Clark, C.M. & Peterson, P.L., “Teachers’ Thought Processes,” in Wittrock, M.C. (Ed.), Hand book of research on teaching, (NY: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1986), pp. 255-296.

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices Years of Teaching Less than 4 years 1 2 4 years – less than 8 years 4 10

More than 10 years 37 88

Degree of Education Master 27 64

Ph.D. 15 36 Specialty TESOL 19 45 Linguistics 8 19 Literature 7 17 Curriculum 3 7 Other 5 12

Native Language Mandarin Chinese 29 69

English 13 31 Approach Bottom-Up 3 7 Top-Down 10 24 Interactive 27 64 Other 2 5 N=42

The vast majority, 37 (88%) were experienced English instructors having more than 10 years’ teaching experience. Among them, 27 (64%) was specialized in either TESOL or Linguistics, whereas 7 (17%) were literature majors. In addition, 29 (69%) out of 42 were native speakers of Mandarin Chinese, while 13 (31%) were native speakers of English. There were 27 (64%) participants reporting that they believed the interactive approach was the most effective approach in teaching reading; 10 (24%) preferred to the top-down approach; only 3 (7%) of them favored the bottom-up approach.

B. Instrument

The Teaching English Reading Questionnaire used in the current study was written both in Chinese and English for Chinese and foreign teachers respectively (see Appendixes A and B). The questionnaire adapted Likert scales 1 to 5, in which 1 indicates the least importance or the least agreement on a certain statement, while 5 refers to the most important or strongest agreement of the item. This questionnaire was used to reveal the diversity of beliefs self-reported by teachers as well as the use of a range of teaching strategies in practical settings.

The questionnaire investigated three parts of teachers’ belief systems: Part A–the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension; Part B–the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and Part C–actual employment of reading theories and strategies in classroom practice. Each part contains 20 identical elements that are considered important factors in reading. The 20 items are classified into five categories of reading strategies. Items 1-3 refer

to linguistic knowledge, such as studying vocabulary or grammar. Item 4 is about translation, namely translating English texts into L1. Items 5-8 are related to conceptually-driven basis, such as activating background knowledge or understanding the connections between paragraphs. Items 9-16 concern cognitive strategies, such as guessing, scanning or skimming. Items 17-18 are about metacognitive strategies, such as monitoring learners’ reading comprehension. Finally, items 19 and 20 are categorized as aided strategies.

Parallel questions were designed in the three parts. For example, Part A focuses on teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and strategies that are important for reading comprehension. Items included are, for example, “I believe that learning vocabulary is important for learners to improve their reading comprehension,” or “I believe that syntactic knowledge is important for learners to improve their reading comprehension.” Part B investigates teachers’ beliefs about ideal instruction of reading. Items included are, for example, “I believe that teaching vocabulary should be included in reading instruction,” or “I believe that teaching syntactic knowledge should be included in reading instruction.” Part C refers to teachers’ self-reported classroom practices. Items included are, for example, “Identify the frequency of teaching vocabulary in your reading class (1 indicates “never” and 5 means “always”),” or “Identify the frequency of teaching syntactic structure in your reading class (1 indicates “never” and 5 means “always”).”

In addition, an open-ended question used to provoke teachers’ self-reported teaching approach and basic personal information was also included.

IV. Analysis and Result

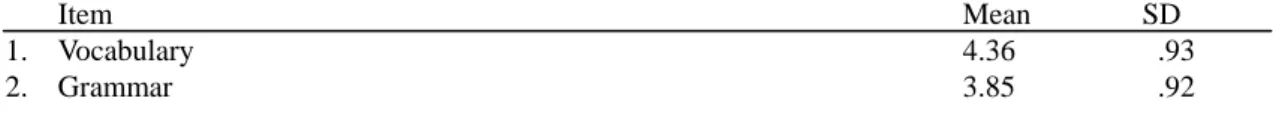

To report the results pertinent to the research questions, the data analyses focus on, first descriptive statistics to understand the construct of teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and strategies among these university instructors. Then, inferential statistics was employed to interpret the relationship between teachers’ beliefs about reading theories and strategies and their practices. Table 2 presents means and standard deviations given to each item in teachers’ beliefs about the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension.

Table 2: Means, Standard Deviations for Each Item in Teachers’ Beliefs about the Importance of Reading Theories and Strategies in reading comprehension

Item Mean SD

1. Vocabulary 4.36 .93

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices 3. Reading aloud the text 3.14 1.38 4. Translating the text into Chinese 2.28 1.06 5. Prior knowledge or background knowledge about

the reading content 3.75 1.04

6. Understanding the connections of each paragraph 3.69 .92 7. Understanding the types of the text 3.19 .94

8. Title 3.66 1.11

9. Guessing the meaning of words 4.21 .68

10. Scanning 3.83 1.03

11. Skimming 3.85 1.04

12. Finding main idea 4.47 .77

13. Summarizing 3.80 1.04

14. Outlining 3.69 1.07

15. Retelling the text 3.50 1.04

16. Predicting the main idea of the following paragraph 3.19 .94 17. Monitoring reading comprehension constantly 3.50 1.10 18. Asking questions to check comprehension 3.80 .89

19. Using dictionaries 3.04 .93

20. Using visual support 3.02 .94

The results showed that the means of 14 out of 20 items (70% of the overall items) were in the high range (mean 5.0-3.5), while 5 items (25% of the overall items) fit the medium range (mean 3.4-2.5). The remaining 1 item was placed in the low range (mean 2.4-1.0).

The three most important teaching theories or strategies advocated by the instructors were “Finding main idea” (Mean 4.47, SD.77), “Vocabulary” (Mean 4.36, SD .93), and “Guessing the meaning of words” (Mean 4.21, SD .68). In addition, the three least important strategies included “Translating the text into Chinese” (Mean 2.28, SD 1.06), “Using visual support” (Mean 3.02, SD .94), and “Using dictionaries” (Mean 3.04, SD .93).

As to each category, Table 3 presents means and standard deviations of the six categories for the three parts, namely the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and actual employment of reading theories and strategies in classrooms.

Table 3: Means, Standard Deviations for Each Category

Category Mean SD

Part A: Importance of Theories/Strategies

Linguistics Knowledge 3.78 .78 Translation 2.28 1.06 Conceptually-driven Basis 3.58 .76 Cognitive Strategy 3.82 .67 Metacognitive Strategy 3.65 .81 Aided Strategy 3.03 .71 Overall 3.59 .53

Part B: Necessity of Theories/Strategies in Teaching

Linguistics Knowledge 3.62 .94 Translation 2.50 1.13 Conceptually-driven Basis 3.44 .75 Cognitive Strategy 3.90 .68 Metacognitive Strategy 3.81 .64 Aided Strategy 3.42 .89 Overall 3.64 .53

Part C: Actual Employment of Theories/Strategies

Linguistics Knowledge 3.65 .89 Translation 2.52 1.38 Conceptually-driven Basis 3.45 .70 Cognitive Strategy 3.61 .68 Metacognitive Strategy 3.68 .75 Aided Strategy 2.91 .84 Overall 3.47 .47

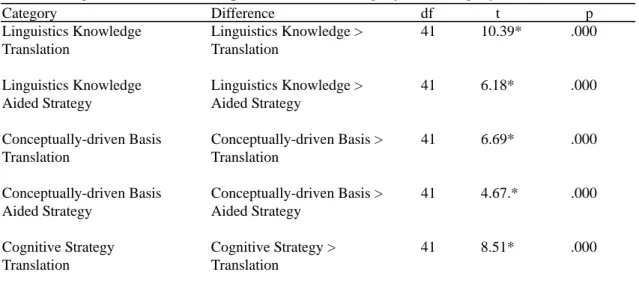

T-tests were computed using the mean scores to compare teachers’ beliefs about the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension between these six categories. An acceptable significance level was deemed to be p < .05. Table 4 presents paired sample t-tests for mean differences between these six categories.

Table 4: Significant Paired Sample T-tests for Category vs. Category

Category Difference df t p

Linguistics Knowledge Linguistics Knowledge > 41 10.39* .000 Translation Translation

Linguistics Knowledge Linguistics Knowledge > 41 6.18* .000 Aided Strategy Aided Strategy

Conceptually-driven Basis Conceptually-driven Basis > 41 6.69* .000 Translation Translation

Conceptually-driven Basis Conceptually-driven Basis > 41 4.67.* .000 Aided Strategy Aided Strategy

Cognitive Strategy Cognitive Strategy > 41 8.51* .000 Translation Translation

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices Cognitive Strategy Cognitive Strategy > 41 5.82* .000 Aided Strategy Aided Strategy

Cognitive Strategy Cognitive Strategy > 41 2.18* .035 Conceptually-driven Basis Conceptually-driven Basis

Metacognitive Strategy Metacognitive Strategy > 41 7.16* .000 Translation Translation

Metacognitive Strategy Metacognitive Strategy > 41 4.58* .000 Aided Strategy Aided Strategy

Aided Strategy Aided Strategy > 41 5.21* .000 Translation Translation

*Significant at the .05 level.

From the analyses of paired sample t-tests, these participants believed linguistics knowledge was significantly more important than translation, t (41) = 10.39, p < .0001 and aided strategy, t (41) = 6.18, p < .0001. Conceptually-driven basis was significantly more important than translation t (41) = 6.69, p < .0001 and aided strategy, t (41) = 4.67, p < .0001. Cognitive strategy was significantly more important than translation, t (41) = 8.51, p < .0001, aided strategy, t (41) = 5.82, p < .0001 and conceptually-driven basis, t (41) = 2.18, p = .035. Metacognitive strategy was significantly more important than translation, t (41) = 7.16, p < .0001 and aided strategy, t (41) = 4.58, p < .0001. Finally, aided strategy was believed more important than translation, t (41) = 5.21, p < .0001.

In summary, the rank orders for these six categories could be identified as: cognitive strategy/linguistics knowledge/metacognitive strategy, conceptually-driven basis, aided strategy, and translation. In other words, the participants believed that cognitive strategy, linguistics knowledge and metacognitive strategy were the most important strategies in reading comprehension. Cognitive strategy in turn is significantly more important than conceptually-driven basis. Finally, aided strategy and translation are the least important strategies in reading comprehension.

Checking the reliability of the questionnaire, Table 4 indicates the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the 60 items and that of the three parts. The internal consistency reliability as measured by Cronbach’s alpha for the entire inventory computed on 42 participants was. 93. For Part A, Cronbach’s alpha achieved a coefficient of .86, for Part B .85 and for Part C .76. Since Nunnaly

(1978)37 indicated 0.7 to be an acceptable reliability coefficient, the above

37

coefficients are all acceptable. A possible explanation for the comparatively low coefficient of .76 for Part C may be that the correlation between the items in Part C has somewhat decreased. It implies that the discrepancy among each participant for each item in Part C is comparatively larger than in both Parts A and B.

Table 5: Internal Consistency Reliability of the Reading Theories and Strategies

Scale Alpha

Part A: Importance of Theories/Strategies .86 Part B: Necessity of Theories/Strategies in Teaching .85 Part C: Actual Employment of Theories/Strategies .76

Entire Questionnaire .93

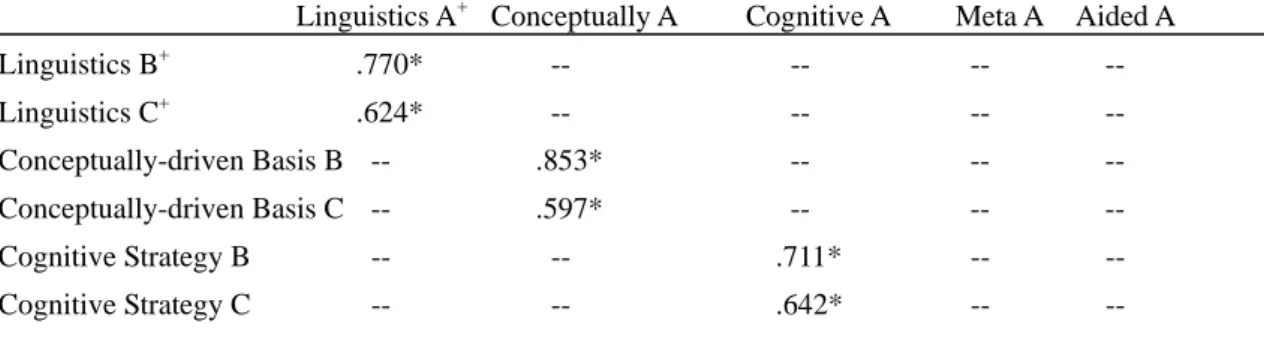

Spearman’s rho was computed to investigate the correlation between the three parts as well as the six categories of reading theories and strategies. The data provided strong evidence that the three parts--the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and actual employment of reading theories and strategies in practical classrooms, were correlated with each other (see Table 5). The positive correlation indicated that the degree of importance of each part increased as its counterpart similarly did.

Table 6: Correlations between the Three Parts of Reading Theories and Strategies

Importance Necessity Employment

Importance of Theories/Strategies 1.000 .745* .576* Necessity of Theories/Strategies in Teaching .745* 1.000 .694* Actual Employment of Theories/Strategies .576* .694* 1.000 *Correlations are significant at the .05 level (1-tailed).

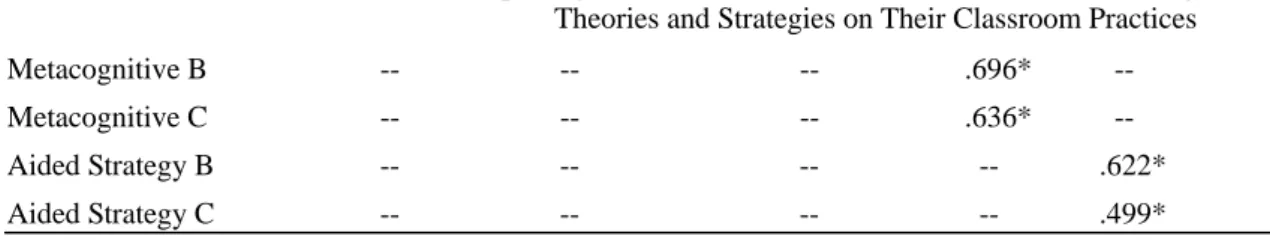

Details about each category within the three parts were also reported (see Table 6). The positive correlation has shown that the increasing degree of importance of each category corresponded with its counterparts.

Table 7: Correlations between the Categories of Reading Theories and Strategies

Linguistics A+ Conceptually A Cognitive A Meta A Aided A Linguistics B+ .770* -- -- -- -- Linguistics C+ .624* -- -- -- -- Conceptually-driven Basis B -- .853* -- -- -- Conceptually-driven Basis C -- .597* -- -- -- Cognitive Strategy B -- -- .711* -- -- Cognitive Strategy C -- -- .642* -- --

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices Metacognitive B -- -- -- .696* -- Metacognitive C -- -- -- .636* -- Aided Strategy B -- -- -- -- .622* Aided Strategy C -- -- -- -- .499* *Correlations are significant at the .05 level (1-tailed).

+

A, B & C refer to Part A: the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, Part B: the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and Part C: actual employment of reading theories and strategies in practical classrooms

Multivariate tests were used to examine the difference between the participants’ self-reported effective approach-the bottom-up, top-down or interactive approach, and the beliefs about and the use of each category. As a result, there were no significant differences between the participants’ beliefs and their use of each approach.

Furthermore, a MANOVA was conducted to identify any significant differences between independent variables and teachers’ beliefs. Table 7 summarizes the MANOVA results, focusing on the significant level at .05.

Table 8: Summary of the MANOVA for the Independent Variables on Reading Theories and Strategies

Source Dependent Variables Type III

Sum of Mean

Squares df Square F p

Nationality Conceptually-driven Basis A+ 1.163 1 1.163 4.717 .049 Aided Strategy A 1.920 1 1.920 5.386 .037

Conceptually-driven Basis C+ 8.721 1 8.721 15.518 .001 Aided Strategy C 3.760 1 3.760 8.647 .008 Gender Aided Strategy B+ 1.952 1 1.952 6.133 .023

+

A, B & C refer to Part A: the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, Part B: the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and Part C: actual employment of reading theories and strategies in practical classrooms

Further investigation of the mean differences of the reading theories and strategies among different nationality and gender was conducted. The post hoc Tukey tests showed that the mean of Chinese instructors who believed that conceptual-driven basis (Mean 3.71 vs. Mean 3.02, Std. Error .023) and the mean of aided strategy (Mean 3.31 vs. Mean 2.5, Std. Error .269) were significantly higher than those of foreign instructors. Chinese teachers also reported that they employed conceptually-driven basis (Mean 4.03 vs. Mean 3.02, Std. Error .284) and aided strategy (Mean 3.30 vs. Mean 2.25, Std. Error .250) significantly more often than did foreign instructors.

As to gender, more female instructors believed that aided strategy (Mean 3.69 vs. Mean 2.28, Std. Error .265) should be taught in reading classes than did male instructors.

V. Conclusion

The current study, accomplished the goals of identifying the construct of teachers’ belief systems. The results indicated that the participants highly believed that a wide range of reading strategies were important in reading comprehension. The items were ranged from the high level (70% of the overall items) to the medium (25% of the overall items). The participants were also unanimous in rating the remaining item, “translating the text into Chinese” as the least important strategy in reading comprehension.

In regards to each specific category of reading theories and strategies, the instructors reported that they believed cognitive strategy, linguistics knowledge and metacognitive strategy were effective in reading comprehension. Evidence also could be found that the most important teaching theories or strategies were all located among these three categories. For example, the items “finding main idea,” and “guessing the meaning of words” belong to the category of cognitive strategy. The items such as “vocabulary” and “grammar” refer to linguistic knowledge.

On the other hand, the strategies, “using visual support,” and “using dictionaries” categorized as aided strategy were ranged as least important elements in reading comprehension. To summarize, the focus on cognitive strategy, linguistics knowledge, and metacognitive strategy has delineated the construct of teachers’ belief systems among those university instructors who participated in this study.

Second, the three parts of the beliefs systems–the importance of reading theories and strategies in reading comprehension, the necessity of reading theories and strategies in teaching practices, and actual employment of reading theories and strategies in practical classrooms, were strongly correlated with each other. Furthermore, the study also reveals that the six specific categories (linguistics knowledge, translation, conceptually-driven basis, cognitive strategy, metacognitive strategy and aided strategy) correspond with their counterparts within each of the three parts. This finding provided evidence that the participants may have reflected the beliefs on their teaching practices. The results have resonated with the factor that the way the instructors practice teaching activities in their reading class depends, to a

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

large extent, on their beliefs about learners, learning and theories (i.e., Nespor, 1987;

Pajares, 1992).38

Third, the result showed no significant differences between the participants’ self-reported effective approach–the bottom-up, top-down or interactive approach, and the beliefs about and the use of each category. A possible explanation for this result may be that the majority of the instructors (64%, 27 out of 42) claimed that they believed the interactive approach was the most effective approach in teaching EFL reading. The high ratio seemed to be the major reason that caused the undifferentiated result. However, another issue needs to be considered--whether the self-reported approach can really reflect the corresponding practices. It might be possible that the instructors do not tend to adopt a bottom-up approach exclusively because students at university level have obtained at least basic grammar and vocabulary knowledge. For further research, applying qualitative research methods, such as interview or observation might help provide insight into this issue.

Finally, native or nonnative instructors of English seemed to have different concerns regarding conceptually-driven basis and aided strategy in reading comprehension and actual employment in their teaching practices. It is possible to hypothesize that instructors who are nonnative speakers of English are inclined to believe and use significantly more holistic strategies and extra-aided strategies, such as visual support or dictionaries in their classroom to maximize students’ learning ability. In addition, more female instructors believe that aided strategy should be taught in reading classes than did male instructors. The result might be related to females’ use of learning strategies as language learners. Some research dealing with observed gender differences in the use of strategies has revealed that females appeared to use a far wider range of language learning strategies than did males

(Oxford & Nyikos, 1989; Green & Oxford, 1995).39 Therefore, female instructors

might tend to seek more aided strategies in their classroom practices.

The findings of the current study provide insight into the exploration of teachers’ beliefs and understanding classroom realities for both researchers and educators. They also may have implications for teacher educators because there is need to understand how instructors practice in the classroom and how to develop the process to become excellent teachers. The current study analyzed university

38

Nespor, J., op cit, pp.317-328; Pajares, M.F., op cit, pp.307-332.

39

Oxford, R.L. & Nyikos, M. “Variables Affecting Choice of Language Learning Strategies by University Students,” Modern Language Journal, No.73 (1989), pp.291-300. Green, J.M. & Oxford, R.L. “A Closer Look at Learning Strategies, L2 Proficiency, and Gender,” TESOL Quarterly, No.29 (1995), pp.261-297.

teachers’ belief systems about teaching reading to EFL learners and offered a better understanding about their teaching practices.

The results have also important implications for both pre-service and in-service teacher professional development programs. Some teacher educators posit that research discussion about how best to improve the effectiveness of reading instruction is based on fundamental beliefs about teacher knowledge and the relationship between theory and practice. On the one hand, teacher educators need to make sure that teachers have access to valid theories and also to assist them to apply theories to practice. Instructors can engage in theory construct or theory learning through their critical inspection of their own theories of action. On the other hand, focus can be placed on improving teachers’ understanding about the relationship between their beliefs and pedagogical practices. Teachers are supposed to gain the knowledge about the educational implications of their beliefs. Then by applying these implications, teachers can utilize a variety of approaches while providing reading instructions or assisting students with improving their reading comprehension. Therefore, both beliefs and understanding about reading can be integrated into meaningful classroom practices for students.

Although an effort has been made to ensure reliability and achieve validity in the current study, some limitations exist. First, the questionnaire based on retrospective self-report depended on the awareness of the participants’ behaviors without observations of practice. In addition, due to the limited sample size and the sampling method, the possibility of generalizing the results may also be limited.

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

References

Anderson, N. Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies, Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999.

Bernhardt, E. B. “Reading in the Foreign Language,” in B. H. Wing (ed.), Listening,

Reading, and Writing: Analysis and Application, Middlebury, VT: Northeast

Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986, pp.93-115.

Bernhardt, E. B. Reading Development in a Second Language: Theoretical,

Empirical, and Classroom Perspectives. Norwood: Ablex Publishing

Corporation, 1991.

Borg, S. “Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching: A Review of Research on What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe, and Do,” Language Teaching, 36 (2003), pp.81-109.

Clark, C.M. & Peterson, P.L. “Teachers’ Thought Processes,” in Wittrock, M.C. (Ed.), Hand book of research on teaching, NY: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1986, pp.255-296.

Coady, J. A. “Psycholinguistic Model of the ESL Reader,” in Mackay, R.; Barkman, B. & Jordan R.R. (Eds.), Reading in a Second Language. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1979.

Collie Garden, E. “How Language Teachers’ Beliefs about Reading are Mediated by Their Beliefs about Students,” Foreign Language Annals, Vol.29, No.3 (1996),

pp.387-95.

Davis, M.M. & Wilson, E.K. “A Title 1 Teacher’s Beliefs, Decision-making, and Instruction at the Third and Seventh Grade Levels,” Reading Research and

Instruction, Vol.38, No.4 (1999), pp.290-299.

Everson, M. E. & Ke, C. “An Inquiry into the Reading Strategies of Intermediate and Advanced Learners of Chinese as a Foreign Language,” Journal of the Chinese

Language Teachers Association, No.32 (1997), pp.1-20.

Farrell, T.S.C. “Grammar Teaching: A Case Study of Teachers' Beliefs and Classroom Practices,” TESL-EJ, (September 2005).

Flores, B.B. “Bilingual Education Teachers’ Beliefs and Their Relation to Self-reported Practices,” Bilingual Research Journal, Vol.25, No.3 (2001), pp.251-275.

Goodman, K.S. “Reading: a Psycholinguistic Guessing Game,” in Singer H. & Ruddell, R.B. (Eds.), Theoretical Models and process of Reading, Newark, DE: International Reading Association, 1976, pp.497-450.

Green, J.M. & Oxford, R.L. “A Closer Look at Learning Strategies, L2 Proficiency, and Gender,” TESOL Quarterly, No.29 (1995), pp.261-297.

Harvey, O.J. “Belief Systems and Attitudes Toward the Death Penalty and Other Punishments,” Journal of Psychology, No.54 (1986), pp.143-159.

Hoffman, J.V. & Kugle, C. “A Study of Theoretical Orientation to Reading and Its Relationship to Teacher Verbal Feedback During Reading Instruction,” Journal

of Classroom Interaction, No.18 (1981), pp.2-7.

Johnson, K.E. “The Relationship between Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices DuringLiteracy Instruction for Non-native Speakers of English,” Journal of

Reading Behavior, Vol.24, No.3 (1992), pp.83-108.

Kamil, M.L. “Reading in the Native Language,” in Wing, B.H. (Ed.), Listening,

Reading, and Writing: Analysis and Application, Middlebury, VT; Northeast

Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986, pp.71-91.

Kane, R., Sandretto, S. & Heath, C. “Telling Half the Story: A Critical Review of Research on the Teaching Beliefs and Practices of University Academics,”

Review of Educational Research, Vol.72, No.2 (2002), pp.177-288.

McPherson, P. “Review of Exploring Second Language Reading: Issues and Strategies,” Reading in a Foreign Language, Vol.15, No.1 (2003).

Nunnaly, J. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978. Nespor, J. “The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching,” Journal of Curriculum Studies, No.19 (1987), pp.317-328.

Oxford, R.L. & Nyikos, M. “Variables Affecting Choice of Language Learning Strategies by University Students,” Modern Language Journal, No.73 (1989), pp.291-300.

Pajares, M.F. “Teachers Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning Up a Messy Construct,” Review of Educational Research, Vol.62, No.3 (1992), pp. 307-332. Rumelhart, D.E. “Toward an Interactive Model of Reading,” in Dornic, S. (Ed.),

Attention and performance VI, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1977,

pp.573-603.

Sigel, I.E. “A Conceptual Analysis of Beliefs,” in Sigel, I.E. (Ed.), Parental Belief

Systems: the Psychological Consequences for Children, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum,

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

Swaffar, J. K. & Bacon, S. “Reading and Listening Comprehension: Perspectives on Research and Implications for Practice,” in Hadley, A.O. (Ed.), Research in

Language Learning, Lincolnwood: National Textbook Company, 1993,

pp.124-155.

Weinstein, C.S. “Teacher Education Students’ Perceptions of Teaching,” Journal of

Teacher Education, Vol.40, No.2 (1989), pp.53-60.

Williams, M. & Burden, R.L. Psychology for Language Teachers: A Social

Constructivist Approach, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Woolacott, T. “Teaching Reading in the Upper Primary School: a Comparison of Two Teachers’ Approaches,” Brisbane, Australia: Annual conference of the Australian, Association for Research in Education, December, 2002.

Appendix A: Teaching English Reading Questionnaire

(English Version)

Directions:

The purpose of this questionnaire is to investigate your beliefs about reading theories and strategies/skills in reading comprehension. There are no right or wrong answers to the statements in the questionnaire. All the answers will be kept confidential and no identity will be disclosed.

This questionnaire consists of two parts. Part One contains Sections A, B and C. There are 20 items in each section:

Section A: investigating what you believe about the importance of reading theories/strategies for reading comprehension.

Section B: investigating what you believe about the necessity of reading theories/strategies in teaching practice

Section C: investigating actual employment of reading theories/strategies in your reading classroom Part Two includes 6 questions related to your background information.

The results will be sent to you once the analyses have been done. If you have any questions about this questionnaire or this project, please contact:

Yu-Chen Chou, Assistant Professor Dept. of Foreign Languages and Literature Feng Chia University

(04) 2451-7250 Ext. 5647 ycchou@fcu.edu.tw

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

Part I: Reading Theory/Strategy

Section A: The Importance of Reading Theories/Strategies for Reading Comprehension

How do you rate the importance of the following items according to their role in reading comprehension? Please check the degree of importance of each item for reading comprehension.

1 Not important 2 Less important 3 Somewhat important 4 Very important 5 Extremely important 1 2 3 4 5 1. Vocabulary □ □ □ □ □ 2. Grammar □ □ □ □ □

3. Reading aloud the text □ □ □ □ □ 4. Translating the text into Chinese □ □ □ □ □ 5. Prior knowledge or background knowledge

about the reading content □ □ □ □ □ 6. Understanding the connections of each paragraph □ □ □ □ □ 7. Understanding the types of the text (i.e. exposition,

comparison and contrast) □ □ □ □ □

8. Title □ □ □ □ □

9. Guessing the meaning of words □ □ □ □ □

10. Scanning □ □ □ □ □

11. Skimming □ □ □ □ □

12. Finding main idea □ □ □ □ □

13. Summarizing □ □ □ □ □

14. Outlining □ □ □ □ □

15. Retelling the text □ □ □ □ □ 16. Predicting the main idea of the following paragraph □ □ □ □ □ 17. Monitoring reading comprehension constantly . □ □ □ □ □ 18. Asking questions to check comprehension □ □ □ □ □

19. Using dictionaries □ □ □ □ □

Section B: The Necessity of Reading Theories/Strategies in Teaching Practices

How do you rate the importance of the following items that should be taught in the reading classes in order to increase students’ reading comprehension? Please check the degree of importance of each item in teaching reading classes.

1 Not important 2 Less important 3 Somewhat important 4 Very important 5 Extremely important 1 2 3 4 5 1. Teaching vocabulary □ □ □ □ □ 2. Teaching grammar □ □ □ □ □

3. Asking students to reading aloud the text □ □ □ □ □ 4. Translating the text into Chinese □ □ □ □ □ 5. Activating prior knowledge or background knowledge □ □ □ □ □ 6. Teaching the connections of each paragraph □ □ □ □ □ 7. Teaching the types of the text (i.e. exposition,

comparison and contrast) □ □ □ □ □

8. Identifying title □ □ □ □ □

9. Teaching students how to guess the meaning of

the words □ □ □ □ □

10. Teaching students how to scan information □ □ □ □ □ 11. Teaching students how to skim the passage □ □ □ □ □ 12. Teaching students how to find main ideas □ □ □ □ □ 13. Teaching students how to summarize □ □ □ □ □ 14. Teaching students how to do outlining □ □ □ □ □ 15. Asking students to retell the text □ □ □ □ □ 16. Asking students to predicting the main idea of the

following paragraph □ □ □ □ □

17. Asking students to monitor reading comprehension

Constantly □ □ □ □ □

18. Asking questions to check comprehension □ □ □ □ □ 19. Teaching students how to use dictionaries □ □ □ □ □ 20. Using visual support □ □ □ □ □

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices Section C: Actual Employment of Reading Theories/Strategies in Your Reading Classroom

How often do you employ the following activities in your reading classes? Please check the frequency of each item used in your reading classes.

1 Never or Almost Never (i.e., you never or almost never employ this activity in your reading classes)

2 Seldom (i.e., if you teach 10 units, you employ this activity in about 2 to 3 units) 3 Sometimes (i.e., if you teach 10 units, you employ this activity in about 5 units) 4 Usually (i.e., if you teach 10 units, you employ this activity in about 7 to 8 units) 5 Always or Almost Always (i.e., you almost always employ this activity in each unit)

1 2 3 4 5

1. Teaching vocabulary □ □ □ □ □

2. Teaching grammar □ □ □ □ □

3. Asking students to reading aloud the text □ □ □ □ □ 4. Translating the text into Chinese □ □ □ □ □ 5. Activating prior knowledge or background knowledge □ □ □ □ □ 6. Teaching the connections of each paragraph □ □ □ □ □ 7. Teaching the types of the text (i.e. exposition,

comparison and contrast) □ □ □ □ □

8. Identifying title □ □ □ □ □

9. Teaching students how to guess the meaning of

the words □ □ □ □ □

10. Teaching students how to scan information □ □ □ □ □ 11. Teaching students how to skim the passage □ □ □ □ □ 12. Teaching students how to find main ideas □ □ □ □ □ 13. Teaching students how to summarize □ □ □ □ □ 14. Teaching students how to do outlining □ □ □ □ □ 15. Asking students to retell the text □ □ □ □ □ 16. Asking students to predicting the main idea of the

following paragraph □ □ □ □ □

17. Asking students to monitor reading comprehension

Constantly □ □ □ □ □

18. Asking questions to check comprehension □ □ □ □ □ 19. Teaching students how to use dictionaries □ □ □ □ □ 20. Using visual support □ □ □ □ □

Part II: Individual Background

The questions below are about your personal background. Please answer the following questions or check the proper answers.

1. Gender: □ Male □ Female 2. Years of Teaching:

□ less than 2 years □ 2 years – less than 4 years □ 4 years – less than 6 years □ 6 years – less than 8 years □ 8 years – less than 10 years □ 10 or more years

3. Degree of Education: □ Bachelor □ Master □ Ph.D. 4. Specialty: □ TESOL □ Linguistics □ Literature

□ Educational Administration □ Curriculum Design □ Other _________________

5. Your Native Language: □ Chinese □ English □ Other _________ 6. The most effective reading approach:

□ Bottom-Up (readers begin the reading process by analyzing the text in small units, and theseunits are built into progressively larger units until meaning can be extracted) □ Top-Down (readers construct meaning by using general knowledge of the world or of particular text components to predict what comes next in the text)

□ Interactive (interactive models disconfirm the linear order of reading processes from the previous two approaches and postulates reading processes can be in both directions) □ Other ___________________________________________________________

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices

Appendix B: Teaching English Reading Questionnaire

(Chinese Version)

英文閱讀教學問卷

說明: 這份問卷的目的在了解您對英文閱讀理論及策略的信念。其中所列的題目,沒有所謂的正確答 案,請根據您的實際狀況回答問題。所有的回答均不記名,結果僅為學術研究之用。 此問卷共分二部份。第一部份共有 A、B、C 三大項,每項共有 20 題。 A 項:調查您認為各題對英文閱讀理解力的重要性。 B 項:調查您認為各題在教學活動中的重要性。 C 項:調查您課堂活動中,使用各題的頻率。 第二部份為個人資料的調查。 結果分析完成後,將致送各位老師參考,謝謝您的合作與參與。若有問題請聯絡: 周玉楨 助理教授 逢甲大學外文系 (04) 2451-7250 Ext. 5647 ycchou@fcu.edu.tw第一部份:英文閱讀教學調查 A:以下各題,您認為其對英文閱讀理解力的重要性為何?請依您所認為的程度打勾。 1 非常不重要 2 不重要 3 普通 4 重要 5 非常重要 1 2 3 4 5 1. 單字 □ □ □ □ □ 2. 文法句型 □ □ □ □ □ 3. 課文唸出聲音 □ □ □ □ □ 4. 翻譯成中文 □ □ □ □ □

5. 背景知識(prior knowledge or background knowledge) □ □ □ □ □

6. 了解段落的連接性 □ □ □ □ □ 7. 對文體的了解(如:說明文、比較文) □ □ □ □ □ 8. 讀標題(title) □ □ □ □ □ 9. 猜測字彙的意思 □ □ □ □ □ 10. 掃描重點(scan) □ □ □ □ □ 11. 略讀大意(skim) □ □ □ □ □ 12. 找主旨(main idea) □ □ □ □ □ 13. 做摘要(summary) □ □ □ □ □ 14. 做大綱(outline) □ □ □ □ □ 15. 重述課文(retell) □ □ □ □ □ 16. 預測下一句或下一段的大意(predict) □ □ □ □ □ 17. 閱讀時不斷地監測自己的理解力(monitor) □ □ □ □ □ 18. 回答問題,以監測理解力(question) □ □ □ □ □ 19. 使用字典 □ □ □ □ □ 20. 圖像或其他視覺的輔助(visual support) □ □ □ □ □

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices B:為增進學生的英文閱讀能力,您認為以下各題,在教學活動中的重要性為何? 請依您所認為的程度打勾。 1. 非常不重要 2. 不重要 3. 普通 4. 重要 5. 非常重要 1 2 3 4 5 1. 教單字 □ □ □ □ □ 2. 教文法句型 □ □ □ □ □ 3. 要求學生將課文唸出聲音 □ □ □ □ □ 4. 翻譯成中文 □ □ □ □ □ 5. 教背景知識 □ □ □ □ □ 6. 分析段落的連接性 □ □ □ □ □ 7. 教文體分析(如說明文、比較文) □ □ □ □ □ 8. 解析標題 □ □ □ □ □ 9. 教猜測字彙的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 10. 教掃描(scan)重點的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 11. 教略讀(skim)大意的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 12. 教訓練找出主旨的能力(main idea) □ □ □ □ □ 13. 訓練做摘要(summary)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 14. 訓練做大綱 (outline)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 15. 訓練重述課文(retell)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 16. 訓練預測下一句或下一段大意的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 17. 訓練閱讀時不斷地監測自己理解力的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 18. 要求學生回答問題以監測閱讀理解力 □ □ □ □ □ 19. 教授如何使用字典及使用字典的時機 □ □ □ □ □ 20. 討論圖像或其他視覺的輔助 □ □ □ □ □

C:在您的課堂活動中,您使用以下各題的頻率為何?請依您所認為的程度打勾。 1. 從未(在教一個單元時,從未做此教學活動) 2. 偶爾做(例如:若教十課,十課中有二、三課會做此教學活動) 3. 有時做有時不做(例如:若教十課,十課中有五課會做此教學活動) 4. 經常做(例如:若教十課,十課中有七、八課會做此教學活動) 5. 總是做(例如:若教十課,每一課會做此教學活動) 1 2 3 4 5 1. 教單字 □ □ □ □ □ 2. 教文法句型 □ □ □ □ □ 3. 要求學生將課文唸出聲音 □ □ □ □ □ 4. 翻譯成中文 □ □ □ □ □ 5. 教背景知識 □ □ □ □ □ 6. 分析段落的連接性 □ □ □ □ □ 7. 教文體分析(如說明文、比較文) □ □ □ □ □ 8. 解析標題 □ □ □ □ □ 9. 教猜測字彙的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 10. 教掃描(scan)重點的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 11. 教略讀(skim)大意的技巧 □ □ □ □ □ 12. 教訓練找出主旨的能力(main idea) □ □ □ □ □ 13. 訓練做摘要(summary)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 14. 訓練做大綱 (outline)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 15. 訓練重述課文(retell)的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 16. 訓練預測下一句或下一段大意的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 17. 訓練閱讀時不斷地監測自己理解力的能力 □ □ □ □ □ 18. 要求學生回答問題以監測閱讀理解力 □ □ □ □ □ 19. 教授如何使用字典及使用字典的時機 □ □ □ □ □ 20. 討論圖像或其他視覺的輔助 □ □ □ □ □

Theories and Strategies on Their Classroom Practices 第二部份:個人資料 以下的問題是有關您的個人資料,請打勾或填寫適當的答案。 1. 性別: □ 男 □ 女 2. 教學年資: □ 2 年以下 □ 2 年以上 – 4 年以下 □ 4 年以上 – 6 年以下 □ 6 年以上 – 8 年以下 □ 8 年以上 – 10 年以下 □ 10 年以上 3. 最高學歷: □ 大學 □ 碩士 □ 博士 4. 最高學歷之專業: □ 英語教學 □ 語言學 □ 文學 □ 教育行政 □ 課程設計 □ 其他_________________(請填寫) 5. 您的母語: □ 中文 □ 英文 □ 其他______(請填寫) 6. 您認為最有效的英文閱讀法: □由下而上(閱讀由「文字」主導,透過組合「字」,從而理解「句子/文章」的意思) □由上而下(概括看句子/文章,推敲箇中意義,繼而再仔細看個別字、句的含意, 再整合、重新理解出最完整的意思。) □互動模式(包含下至上模式與上至下模式的特點,閱讀可以從「字」入手, 也可從整體「含義」入手。) □其他_(請填寫)

第 183-216 頁 2008 年 6 月 逢甲大學人文社會學院