ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Health-related quality of life and cognitive outcomes

among child and adolescent survivors of leukemia

Shyh-Shin Chiou&Ren-Chin Jang&Yu-Mei Liao&

Pinchen Yang

Received: 5 May 2009 / Accepted: 9 November 2009 / Published online: 1 December 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009

Abstract

Purpose Long-term survival of childhood leukemia has become a reality with treatment advancement; hence, the need to assess the survivors’ health-related quality of life (HRQL) is essential. Although a growing number of Western studies have documented the considerable impact of diagnosis and treatment on HRQL in pediatric leukemia survivors, little finding has been reported in non-Western developing countries.

Methods We used a previously validated 14-dimensional questionnaire, Child Health Questionnaire 50-item Parent Form (CHQ-PF 50), to examine the perceived HRQL of 32 child/adolescent survivors, currently aged 13.17±2.49 years, who had experienced first complete continuous remission from leukemia for at least 3 years. The HRQL status was compared with that obtained from community subjects (N=154) and survivors’ nonadult siblings (N=30). Intelli-gence quotients (IQ) and computerized neuropsychological assessments were performed for subjects.

Results The HRQL of leukemia survivors was noted to be worse than that of community children and nonadult siblings as reflected by significantly lower scores in both the physical summary and the psychosocial summary score of CHQ-PF 50. 15.6% of the survivors had impaired intelligence (estimated IQ below 70). 27.8% of the adolescents were impaired in the cognitive domains as assessed by neuropsy-chological tests.

Conclusions In this Taiwanese single institution experience, pediatric leukemia survivors carried a morbidity burden into their teen years as reflected by worse HRQL than controls. These findings may guide the support required by this population.

Keywords Cancer survivor . Health-related quality of life . Pediatric leukemia . Adolescent

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer and is highly responsive to treatment. Among patients receiving contemporary therapy in the developed countries, the overall 5-year survival rate is reported to be 80% to 86% [1] and the 5-year event-free survival rate to be 78% to 83% [2]. The current cure rate of ALL in North American children has improved dramatical-ly from being almost invariabdramatical-ly fatal before the 1960s to becoming one of the malignant diseases with the best prognosis. While ALL therapies are highly effective, western studies have shown excesses of both mortality and morbidity in ALL survivors. These morbidities include early death, second neoplasm, organ dysfunction, impaired growth and development, decreased fertility, and impaired intellectual function [3–8]. With regard to these late

S.-S. Chiou

:

R.-C. Jang:

Y.-M. LiaoDepartment of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

P. Yang

Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

P. Yang (*)

Department of Psychiatry,

Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, 100, Shin-Chuan 1st Road,

Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan e-mail: pichya@kmu.edu.tw

morbidities, the negative impacts of such sequelae on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL) are also beginning to be reported [9–13].

HRQL is a multidimensional construct defined as the patient’s “subjective perception of the impact of health status, including disease and treatment, on physical, psychological and social functioning” [14]. Instruments that assess HRQL can complement efficacy measures in clinical trials to provide a more thorough picture of the impact of disease and treatment on one’s overall well-being. Definition of children’s HRQL has been based on function or disabilities or in terms of a match between aspirations and experience [15]. Since children do not share adult views about the cause, etiology, and treatment of illness and they may also adopt a different time perspective regarding the course of a disease; we have to take the child’s age and development into account. Any ideal HRQL measures for children need to have an in-built sensitivity to accommo-date the normative changes that will be expected to occur during childhood.

The majority of the follow-up cancer survivor studies in HRQL of life have been done in developed countries. The experiences in Asian developing countries are few in the literature. The aim of the present study was to assess the HRQL and cognitive functions in a Han Chinese sample of childhood leukemia survivors treated at a single institution in Taiwan. For Taiwanese children diagnosed as ALL between 1982 and 1993, the overall and event-free survival rates were noted to be 70±4.1% and 64±4.3%, respectively [16]. Treatment dropout rate for childhood leukemia used to be high, mainly due to financial difficulties. The current survival expectation of pediatric ALL is thought to be better than 70% since the adoption of a National Health Insurance scheme in 1995, which covers more than 96% of Taiwan’s population. With the increasing survival rates for childhood leukemia, it is essential that we focus attention not only on “cure” per se but also on helping survivors to achieve a future that is as normal as possible. Hence, it will be of interest to know the functioning of childhood cancer survivors in Taiwan now that basically every ill child can receive medical treatment.

Materials and methods

Participant

Participants were recruited through“follow-up” Oncology Clinic of Pediatrics at Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Survivors of pediatric ALL who were in the first and complete continuous remission for at least 3 years, who did not undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and were currently aged below 18 years were invited to

participate. Those children with preexisting congenital disorders before receiving the diagnosis of leukemia were excluded. From May 2006 to April 2008, 34 survivors of childhood ALL fulfilling the criteria were identified. Of these 34 potential subjects contacted, two (5.9%) refused participation, which was an acceptable low refusal rate. Two groups of controls were enlisted for the purpose of comparison of the HRQL results with that of the survivors. The first group of controls consisted of children recruited from the community. Through written request and mail-back questionnaire, we invited the willing parents of children who were attending nearby public schools to participate in the study. Children who had major physical disorders requiring prior hospitalization were excluded. In addition, nonadult siblings of the survivors were invited to be our second comparison group for controlling the effect of different socioeconomic status on quality of life. Sibling participation rate was 100% for those approached. Medical information including details of the survivors’ illness and treatment course were obtained via systematic review of each of the subjects’ relevant medical records. This study was approved by the Institute Review Board of the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from subjects’ parents and subjects themselves according to the guidelines of the Institutional Committee on Clinical Investigation.

Final ALL survivors subjects were 32 adolescents (17 boys, 15 girls with current average age of 13.17 ± 2.49 years). All children in this study received treatment according to the existing nationwide protocols of the Taiwan Pediatric Oncology Group (TPOG). Because the treatment initiation year of our leukemia survivors spanned from 1992 to 2005, the protocol they received included TPOG ALL 93, TPOG ALL 97, and TPOG ALL 2002 [17,

18]. Each treatment protocol consisted of four phases of treatment: remission induction, central nervous system prophylactic treatment, consolidation, and continuation therapy. Subjects were diagnosed to have ALL at a mean age of 4.43±2.21 years (ranging from 10 months to 10 years 10 months). The leukemia treatment was discontinued at a mean age of 7.47±2.37 years. The mean survival time to the study date was 8.74±2.26 years. Total hospitalization days for leukemia treatment were at an average of 173.25± 83.98 days. The final community control subjects were 154 children (73 boys, 81 girls with average age of 12.36 years± 2.13 years), while the final nonadult siblings recruited as the control subjects were 30 children (13 boys, 17 girls with average age of 13.45 years±3.18 years; three parents rated more than one sibling, which might cause problems in statistical analysis). Regarding the prophylactic CNS treat-ment, 81.2% (26/32) of the survivors received intrathecal methotrexate only. The remaining six subjects received intrathecal methotrexate in combination with cranial

radio-therapy. The highest cranial radiotherapy dose that the survivors had received was 24 Gy. The diagnostic and treatment information of survivors is presented in Table 1. The physical and psychiatric examination at the time of the study revealed that five of the survivors were obese, one had hypothyroidism, two had hypogonadism, one had generalized anxiety disorder, and one had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, inattentive subtype.

Materials

Data analyzed were collected from two sources: (1) Child Health Questionnaire 50-item Parent Form (CHQ-PF 50) completed by survivors’ primary caregivers, which was given at the time of outpatient visit and completed at home and (2) cognitive data were collected during a 2- to 3-h assessment; details described as follows. The survivors’ parents were asked to complete the CHQ-PF 50 for all their children (i.e., survivors and their siblings) who were currently aged 5–18 years. The CHQ-PF 50 is one of the HRQL instruments, which provides an estimate of the physical and psychosocial well-being of children aged 5–18 years [19]. It contains 50 items measuring 12 domains of physical and emotional health: physical functioning, behavior, self-esteem, role limitations–emotional/behavioral, role limitations–physical, bodily pain, mental health, general health perceptions, parent impact–emotional, parent– impact–time, family activities, and family cohesion. Two summary scores, the psychosocial summary scale and the physical summary scale, are derived from weighted combi-nations of domain subscale scores. The twelve subscales are transformed to a range of 0–100, with 0 indicating worst HRQL and 100 indicating best HRQL. The summary scores

reflect the US population mean at a score of 50, with a 10-point increment for each standard deviation. The CHQ-PF 50 meets the criteria required for quality of life/functional health status instruments with high indices of scale reliability and validity [20]. The Chinese version of CHQ-PF 50 that we used was a validated version obtained from the publisher. For the cognitive functioning, all the survivors received the Information (general knowledge), Similarities (verbal reasoning), and Block design (nonverbal reasoning) subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III [21] to provide the age-corrected estimate of intelligence quotient (EIQ). The EIQ obtained from this abbreviated version is reported to be highly correlated with full scale intelligence quotients [22]. Participants 16 years 6 months and older were administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III [23]. For survivors older than 12 years of age, a nonverbal computerized battery of Mindstreams® (NeuroTrax Corp., NJ, USA) tests was further administered to evaluate high-order cognitive processing ability. This test battery was only given to adolescent subjects because it has psychometric data to support its use on subjects older than 12. The nonverbal battery of Mindstreams® includes the following tests: Non-Verbal Memory test, Go No-Go test, Problem Solving test, Visual Spatial Processing test, Staged Information Processing Speed test, Finger Tapping test, and Catch Game test. Groups of normalized outcome parameters measuring similar cognitive functions were then averaged to produce six index scores, each indexing a different cognitive domain: memory, executive function, visual spatial, attention, information processing speed, and motor skills. Good convergent construct validity has been shown between Mindstreams® assessment battery and traditional neuropsychological tests designed to tap similar cognitive domains [24].

Survivors (N=32) Gender

Male (%) 17 (53.1%)

Female (%) 15 (46.9%)

Current age ± SD, years 13.17±2.49 (8.9–18.9) Mean age at diagnosis ± SD, years 4.43±2.21 (0.8–10.8) Mean age off cancer treatment ± SD, years 7.47±2.37 (3.0–13.2) Mean survival time ± SD, years 8.74±2.26 (5.3–13.9) Total hospitalization days ± SD, days 173.25±83.98 (41–357) Mean EIQ at follow-up ± SD 90.52±16.15 (48–118)

IQ >70 (N, %) N=27 (84.4%)

Prophylactic therapy

IT MTX only N=26

Average cumulative dose (mg) 234.00±48.81 (120–324)

IT MTX+CRT N=6

Average MTX cumulative dose (mg) 162.00±79.16 (108–266) Average CRT dose (Gy) 16.58±4.39 (12–24) Table 1 Demographic and

treatment characteristics of leukemia survivors

EIQ estimated intelligence quotient, IT intrathecal, MTX methotrexate, CRT cranial radiotherapy

Analysis procedures

All statistics were computed using SPSS for Window Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Cron-bach’s alpha reliability analysis for the CHQ-PF 50 used in this study was 0.84. CHQ-PF 50 data of the survivor group were compared with data of the community children and siblings, respectively, using independent t tests after covariance by gender and age. Effect size (EF) was calculated as the mean of the control sample minus the mean of the survivor sample divided by the standard deviation of the control sample [25]. The effect size of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large [26]. Linear regression procedures were used to evaluate the association between the physical and psychosocial summary scores of CHQ-PF 50 and IQ, time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis, current age, off treatment age, total hospitalization days, and intrathecal methotrexate dose.

Results

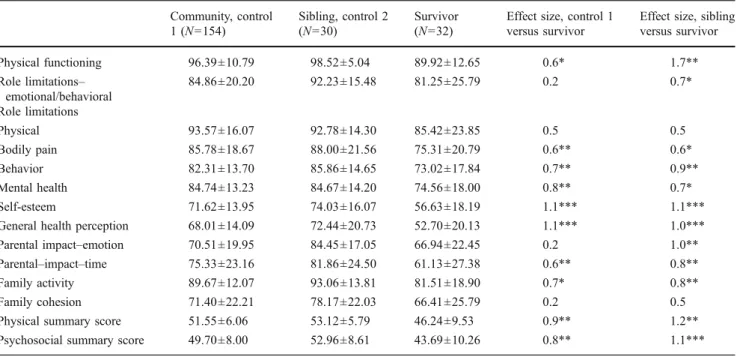

Parents reported leukemia survivors’ HRQL to be signifi-cantly lower than that of the community control group in the physical summary score (EF=0.9, p<0.01), psychoso-cial summary score (EF=0.8; p<0.01), and many CHQ-PF 50 subscales, especially the subscale of mental health, self-esteem, and general health perception. When HRQL was compared between the survivors and their nonadult sib-lings, results also showed survivors’ HRQL to be lower

than the siblings in the physical summary score (EF=1.2, p<0.01), psychosocial summary score (EF=0.8, p<0.001), and many of the CHQ-PF 50 subscales. In addition, the problems of leukemia survivors interfered with family activities and consumed parental time significantly. Never-theless, three parents rated more than one sibling, which is a limitation in our current analysis that has to be reported. Detailed presentation of the comparison on CHQ-PF 50 is presented in Table2. Analysis by linear regression showed no association between CHQ-PF 50 outcome measure and time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis, current age, off treatment age, total hospitalization days, and intrathecal methotrexate dose. Only IQ score were shown to be positively associated with Physical summary score (p=0.02) Of the 32 survivors, 84.4% (27/32) of them had EIQ above 70, and the average EIQ at follow-up was 90.52± 16.15. Of the 18 adolescent survivors who further received the neuropsychological tests for evaluation of cognitive function, 27.8% (5/18) of them were impaired in one or more of the seven assessed cognitive domains (i.e., test scores below the mean score by two standard deviations or more). One subject was impaired in memory; one subject was impaired in executive function, four subjects had impairment in visual spatial ability, and one subject was impaired in motor skills.

Discussion

This is a preliminary study to assess the HRQL and cognitive functioning in child/adolescent survivors of

Table 2 CHQ-PF 50 scale and summary scores: leukemia survivors and control samples Community, control 1 (N=154) Sibling, control 2 (N=30) Survivor (N=32)

Effect size, control 1 versus survivor

Effect size, sibling versus survivor Physical functioning 96.39±10.79 98.52±5.04 89.92±12.65 0.6* 1.7** Role limitations– emotional/behavioral 84.86±20.20 92.23±15.48 81.25±25.79 0.2 0.7* Role limitations Physical 93.57±16.07 92.78±14.30 85.42±23.85 0.5 0.5 Bodily pain 85.78±18.67 88.00±21.56 75.31±20.79 0.6** 0.6* Behavior 82.31±13.70 85.86±14.65 73.02±17.84 0.7** 0.9** Mental health 84.74±13.23 84.67±14.20 74.56±18.00 0.8** 0.7* Self-esteem 71.62±13.95 74.03±16.07 56.63±18.19 1.1*** 1.1*** General health perception 68.01±14.09 72.44±20.73 52.70±20.13 1.1*** 1.0*** Parental impact–emotion 70.51±19.95 84.45±17.05 66.94±22.45 0.2 1.0** Parental–impact–time 75.33±23.16 81.86±24.50 61.13±27.38 0.6** 0.8** Family activity 89.67±12.07 93.06±13.81 81.51±18.90 0.7* 0.8** Family cohesion 71.40±22.21 78.17±22.03 66.41±25.79 0.2 0.5 Physical summary score 51.55±6.06 53.12±5.79 46.24±9.53 0.9** 1.2** Psychosocial summary score 49.70±8.00 52.96±8.61 43.69±10.26 0.8** 1.1*** *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (all levels of significance drawn from independent t test samples)

pediatric leukemia of an Asian developing country. As reported, significant impairments across both constructs of physical and psychosocial domains existed. Regarding the previous western reports of childhood cancer survivors and HRQL, drawn conclusions in the literature on this topic is quite varied; but several studies indicate that childhood cancer survivors are doing quite well, particularly for psychosocial subscales [10,13,27]. However, some studies of the health-related quality of life of pediatric cancer survivors revealed worse scores compared to population norms. Gant and colleagues used a self-complete question-naire, Health Utilities Index, to evaluate the health status and health-related quality of life in eighty-four Canadian adolescent survivors of pediatric cancer [28]. The results showed overall HRQL utility scores to be lower for pediatric cancer survivors than for corresponding members of the general population. Speechley and colleagues compared HRQL of 800 Canadian child and adolescent survivors younger than 16 years using a parent report questionnaire with that of similarly aged individuals from the general population with no history of cancer [29]. Their results also showed that HRQL for survivors was worse than controls. Our results were consistent with these western reports.

To prevent relapse, prophylactic therapies with radio-therapy and/or chemoradio-therapy to prevent leukemia cells infiltrating the central nervous system are needed. A significant body of previous literature confirms that child-ren’s cognitive functioning may be compromised by such kinds of prophylactic therapies [30–33]. Recent treatments have eliminated the use of brain irradiation in low and standard risk ALL. Those with higher risk of recurrence are still treated with cranial radiotherapy but with lower doses (12 to 18 Gy). However, prophylactic therapy using chemotherapy only is still reported to be associated with long-term neuropsychological sequelae [34, 35]. In our follow-up, we found 15.6% of the total survivors to have intellectual deficits (IQ<70) and 27.8% of the adolescent survivors to have subtle cognitive deficit as shown in neuropsychological tests. This finding supported the argument that ALL treatment made impact on cognitive domains. Our sample size is too small to perform further in-depth therapy-specific analysis on this regard. Nevertheless, with these preliminary results, we concluded that cognitive functioning of all children surviving leukemia should be regularly assessed as soon as practicable and be continued for some years after treatment. Comprehensive neuropsychological tests will be preferred because the deficit may be subtle. Appropriate remediation and educational programs can thus be designed accordingly once cognitive impairment is identified.

Our study should be viewed in light of certain limitations. The major limitation of this study is its small

sample size. However, given the paucity of available literature on survivors of pediatric blood cancer in developing countries, as well as the acceptable representativeness of the current sample, it is believed that these findings can be of merit to physicians, parents, and survivors in Asian cultures. In addition, we only provide the experience of one treatment center in Taiwan, which is not national or population-based in scope. A single institution does not have the sufficient number of patients to control for the numerous patient-specific and therapy-specific variables involved. Multi-institutional collaboration for detailed analysis in the future would be needed.

Another major weakness of our survey is that the age of diagnosis of our survivors ranged from infancy (10 months) to late childhood (10 years 10 months). Since the age of the child to acquire a serious illness had a high impact on development, the heterogeneity of the survivor group can be a problem. In addition, the HRQL measure used in this research is based on parent report. Children and parents do not necessarily share similar views about the impact of illness and correlation between the child’s self-report, and the proxy report is not necessarily consistent [36, 37]. However, there are several contexts in which parents are normally able to make judgments for their children, including the impact on family, sibling relationships, and school progress. Parents are less able to make judgments regarding symptom experience, peer relationships, or future worries [38]. It’s not possible to say which one is (more) valid. Each may contribute to the total picture of the child’s quality of life [39, 40]. Our sole use of parental-report CHQ-PF 50 could also be insufficient in that parents may be influenced by the development of other children (such as the survivors’ siblings), their own conceptualization of the illness, their mental health, or additional life stressors [15]. Following the leukemia treatment of the child, the primary caregiver may suffer psychological burdens such as posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. These may all affect the parents’ viewpoints about their children, but regretfully, we did not arrange concurrent assessment on the parents who filled in the questionnaire. We acknowledge this as a weakness in our study. Another point is that our reports address the issue of HRQL in child and adolescent survivors rather than adults. Since adolescence is a time of rapid changes, it would be difficult to make definitive statements regarding the HRQL of this group of survivors when they reach adulthood.

Our findings provide support for the notion that pediatric leukemia survivors still have multiple problems in broader health outcomes as represented by the concept of HRQL. On account of the national insurance plan that Taiwan has currently adopted, we consider the data we obtained to be representative of Taiwanese ALL survivors rather than the condition of the selected few who could afford treatment

and follow-up. Hence health-related quality of life is an issue in families with leukemia survivors of Taiwan as it is in Western developed countries. It would be important to include scales measuring attributes other than clinical symptoms in attempting to evaluate the effectiveness of leukemia treatment. In addition, a more qualitative approach would produce a clearer picture of the well-being and burdens of leukemia survivors and their families. There is need for the continuing follow-up of survivors of childhood leukemia and the provision of the resources to do so, especially among survivors who have not yet reached adulthood.

References

1. Brenner H, Kaatsch P, Burkhardt-Hammer T, Harms DO, Schrappe M, Michaelis J (2001) Long-term survival of children with leukemia achieved by the end of the second millennium. Cancer 92:1977–1983

2. Silverman LB, Gelber RD, Dalton VK, Asselin BL, Barr RD, Clavell LA, Hurwitz CA, Moghrabi A, Samson Y, Schorin MA, Arkin S, Declerck L, Cohen HJ, Sallan SE (2001) Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of Dana-Farber Consortium Protocol 91–01. Blood 97:1211–1218 3. Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, Jaspers MW, Koning CC, Oldenburger F, Langeveld NE, Hart AA, Bakker PJ, Caron HN, van Leeuwen FE (2007) Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297:2705–2715

4. Mody R, Li S, Dover DC, Sallan S, Leisenring W, Oeffinger KC, Yasui Y, Robison LL, Neglia JP (2008) Twenty-five year follow-up among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood 111:5515–5523 5. Oeffinger KC, Eshelman DA, Tomlinson GE, Buchanan GR,

Foster BM (2000) Grading of late effects in young adult survivors of childhood cancer followed in an ambulatory adult setting. Cancer 88:1687–1695

6. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, Schwartz CL, Leisenring W, Robison LL (2006) Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355:1572–1582

7. Pui CH, Cheng C, Leung W, Rai SN, Rivera GK, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, Relling MV, Kun LE, Evans WE, Hudson MM (2003) Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 349:640–649 8. Stevens MC, Mahler H, Parkes S (1998) The health status of adult

survivors of cancer in childhood. Eur J Cancer 34:694–698 9. Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Siimes MA, Hovi L, Holmberg C,

Boyd H, Makela A, Rautonen J (1996) Health-related quality of life of adults surviving malignancies in childhood. Eur J Cancer 32A:1354–1358

10. Langeveld NE, Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF (2002) Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer 10:579–600

11. Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, Shaw AK, Speechley KN (2006) Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:2527–2535 12. Pemberger S, Jagsch R, Frey E, Felder-Puig R, Gadner H,

Kryspin-Exner I, Topf R (2005) Quality of life in long-term childhood cancer survivors and the relation of late effects and subjective well-being. Support Care Cancer 13:49–56

13. Shankar S, Robison L, Jenney ME, Rockwood TH, Wu E, Feusner J, Friedman D, Kane RL, Bhatia S (2005) Health-related quality of life in young survivors of childhood cancer using the Minneapolis-Manchester Quality of Life-Youth Form. Pediatrics 115:435–442

14. Patrick DL, Chiang YP (2000) Measurement of health outcomes in treatment effectiveness evaluations: conceptual and methodo-logical challenges. Med Care 38:II14–II25

15. Eiser C, Morse R (2001) A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child 84:205–211 16. Liu HC, Chen SH, Chang KH, Chiang LC, Liu CY, Chang HL,

Tsai LL, Liang DC (2002) Overall and event-free survivals for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children at a single institution in Taiwan. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 19:19–29

17. Liang DC, Hung IJ, Yang CP, Lin KH, Chen JS, Hsiao TC, Chang TT, Pui CH, Lee CH, Lin KS (1999) Unexpected mortality from the use of E. coli L-asparaginase during remission induction therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Taiwan Pediatric Oncology Group. Leukemia 13:155–160 18. Lin WY, Liu HC, Yeh TC, Wang LY, Liang DC (2008) Triple

intrathecal therapy without cranial irradiation for central nervous system preventive therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50:523–527

19. Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE (1999) The CHQ User’s manual. HealthAct, Boston, MA

20. Waters E, Salmon L, Wake M (2000) The parent-form Child Health Questionnaire in Australia: comparison of reliability, validity, structure, and norms. J Pediatr Psychol 25:381–391 21. Wechsler D (1991) Manual for the Wechsler intelligence scale for

children, 3rd. Psychological Corp, New York

22. Sattler J (1992) Assessment of children, revised and updated version. JM Sattler Publisher, Inc, San Diego

23. Wechsler D (1997) Wechsler adult intelligence scale III. Psycho-logical Corporation, San Antonio, Tex

24. Dwolatzky T, Whitehead V, Doniger GM, Simon ES, Schweiger A, Jaffe D, Chertkow H (2003) Validity of a novel computerized cognitive battery for mild cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr 3:4 25. Lydick E, Epstein RS (1993) Interpretation of quality of life

changes. Qual Life Res 2:221–226

26. Cohen J (1977) Statistical power analysis for behavioral science (Revised Edition). Academic, New York

27. Dolgin MJ, Somer E, Buchvald E, Zaizov R (1999) Quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Soc Work Health Care 28:31–43

28. Grant J, Cranston A, Horsman J, Furlong W, Barr N, Findlay S, Barr R (2006) Health status and health-related quality of life in adolescent survivors of cancer in childhood. J Adolesc Health 38:504–510

29. Speechley KN, Barrera M, Shaw AK, Morrison HI, Maunsell E (2006) Health-related quality of life among child and adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:2536–2543 30. Anderson V, Smibert E, Ekert H, Godber T (1994) Intellectual,

educational, and behavioural sequelae after cranial irradiation and chemotherapy. Arch Dis Child 70:476–483

31. Cousens P, Waters B, Said J, Stevens M (1988) Cognitive effects of cranial irradiation in leukaemia: a survey and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 29:839–852

32. Langer T, Martus P, Ottensmeier H, Hertzberg H, Beck JD, Meier W (2002) CNS late-effects after ALL therapy in childhood. Part III: neuropsychological performance in long-term survivors of childhood ALL: impairments of concentration, attention, and memory. Med Pediatr Oncol 38:320–328

33. Said JA, Waters BG, Cousens P, Stevens MM (1989) Neuropsy-chological sequelae of central nervous system prophylaxis in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Consult Clin Psychol 57:251–256

34. Buizer AI, de Sonneville LM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Veerman AJ (2005) Chemotherapy and attentional dysfunction in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: effect of treatment intensity. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45:281–290

35. von der Weid N, Mosimann I, Hirt A, Wacker P, Nenadov Beck M, Imbach P, Caflisch U, Niggli F, Feldges A, Wagner HP (2003) Intellectual outcome in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated with chemotherapy alone: age-and sex-related differences. Eur J Cancer 39:359–365

36. Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1987) Child/ adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101:213–232

37. Levi RB, Drotar D (1999) Health-related quality of life in childhood cancer: discrepancy in parent-child reports. Int J Cancer Suppl 12:58–64

38. Eiser C (1997) Children’s quality of life measures. Arch Dis Child 77:350–354

39. Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, Verrips GH, Zwinderman KA, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Wit JM (1998) The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res 7:387–397

40. Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M (1999) A comparison of parent and adolescent reports describing the health-related quality of life of adolescents treated for cancer. Int J Cancer Suppl 12:39–45