1

Partisanship and Institutional Trust:

A Comparative Analysis of Emerging Democracies in East Asia

Kai-ping Huang <kaipingh@utexas.edu> The University of Texas at Austin

Feng-yu Lee <fylee323@ntu.edu.tw> National Taiwan University

and

Tse-min Lin <tml@austin.utexas.edu> The University of Texas at Austin

2 Introduction

Trust in political institutions has important political consequences, including a regime’s

legitimacy (Gershtenson, Ladewig, and Plane 2006, p. 883). What are the factors that affect

citizens’ trust in political institutions? Intuitively speaking, citizens trust political institutions

when those institutions perform well (Lipset and Schneider 1987; Hetherington 1998; Putnam

1994). However, how do citizens acquire the information and use it to appraise political

institutions? The media, as the main channel of public information, can of course affect

institutional trust by its coverage of institutional performance and scandals (Orren 1997). In a

more subtle and yet under-developed way, social capital theory argues that institutional trust is

closely associated with vibrant social networking and social trust (Putnam 2001). These theories

view institutional trust as the end product of good government performance and studies in this

vein focus mainly on what factors uphold government performance and the flow of information.

This seemingly objective way of assessing political institutions has shortcomings. Firstly,

trust is a psychological phenomenon. According to a classic definition, “An individual may be

said to have trust in the occurrence of an event if he expects its occurrence and his expectation

leads to behavior which he perceives to have greater negative motivational consequences if the

expectation is not confirmed than positive motivational consequences if it is confirmed”

(Deutsch 1958, p. 266; Warren 1999). Such risk-taking behavior involves not only an objective

assessment of whether the expected event actually occurs but also a subjective calculation on the

part of the trusting person. Secondly, institutional trust is more complicated because political

institutions were designed with different principles and purposes. In particular, some institutions

function through partisan elections while others through more neutral processes. When assessing

3

conflicts with their partisan cognitions. In this paper, we argue that trust in partisan institutions,

vis-à-vis trust in neutral institutions, is likely to be subject to cognitive dissonance, and citizens

may rely their partisanship as a heuristic shortcut in evaluating the trustworthiness of partisan

institutions. Without including partisanship as a subjective factor in the analysis of institutional

trust, we are omitting a variable that may be as important as the objective factors underlying

institutional performance.

Subjective factors of institutional trust are important in established democracies, but they

should be even more important in emerging democracies. This is because political institutions in

emerging democracies are not far removed from these countries’ authoritarian past and are likely

to invoke ambivalent emotions from citizens. Until these emotions completely die down, trust or

suspicion in political institutions may depend on subjective factors in emerging democracies

more than in established democracies.

In this paper, we investigate the effect of partisanship on institutional trust in six emerging

democracies in Ease Asia. Using data from the third wave Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), we

construct indicators of institutional trust and identify their determinants. We focus on

partisanship as our key explanatory variable. Our research question concerns the asymmetric

effect of party ID, i.e., whether identifiers of the opposition parties tend to have weaker

institutional trust. But we also look into different types of political institutions to see if the

asymmetric effect is more pronounced in partisan institutions than in neutral institutions. We

conclude by discussing the implications of our findings on the consolidation of democracy.

Institutional Trust and Its Sources

4

social networking and generalized trust (Putnam 2001). Putnam (1993, 2001) reasons as social

capital develops, it also helps build efficient and effective political institutions, which in turn

boost people’s trust in those institutions. The social capital theory, however, has raised some

theoretical questions and lacked consistent empirical support. Theoretically, the working

mechanism of how generalized trust and social networking helps improve government

performance is unclear. To Putnam, it seems that social capital contributes to government

performance through two means. The first is civic responsibility as a response to social trust; and

the second is civic engagement with public concerns in mind (1993). The two mechanisms,

however, are based on different logics. While the first requires self-consciousness and honesty of

politicians and officials to perform well, the later is actually a monitoring mechanism that keeps

politicians/officials accountable. In other words, social capital is paradoxically begetting both

trustworthy politicians and suspicious citizens at the same time. While this paradox may be

inherent in the classic concept of trust, i.e., trust is essentially a risk-taking behavior and hence

the trusting party must be wary of the trusted party, it does render dubious the causal effects of

social capital on institutional trust.

Besides its theoretical ambiguity, social capital theory also faces mixed empirical support.

Cross-national comparison of institutional trust shows that social trust is positively correlated

with institutional trust in advanced democracies (Newton and Norris 2000). In the United States,

earlier levels of social trust were found to contribute to institutional trust in the later time, but

social networking only has a modest effect on institutional trust (Damico, Conway, and Damico

2000). In newly democratized countries, such as South Korea, it was found that civic

engagement had no effect on institutional trust while social trust is negatively correlated with

5

scholars suggest that all political institutions are not the same because that they were designed

with different principles and purposes. It is therefore necessary to distinguish different types of

political institutions in investigating the causal relationship between social capital and

institutional trust.

Institutional Trust and Types of Political Institutions

When investigating institutional trust, researchers usually lump all political institutions

together to form a single measure of institutional trust. Rothstein and Stolle (2008) criticized

such a one-dimensional view. Firstly, some institutions, such as the executive office and the

parliament, are supposed to operate along partisan lines. In democracies, these institutions are

organized by elections in which political parties with different platforms compete for control.

After an election, citizens expect these institutions to make policies consistent with the ideology

of the party that wins the election. Under such a premise, confidence in these institutions is likely

to vary among citizens according to whether or not they identify with the incumbent party. Thus,

associating trust in these institutions with social trust only may be misleading if partisanship is

not taken into account. Secondly, other political institutions, such as the courts, the military, and

the police are supposed to operate in an impartial, non-partisan manner. These institutions are

crucial for maintaining the order and efficiency of governance. Hence, if trust is a risk-taking

behavior, the performance of these institutions is pertinent with the development of social trust

since they are the institutions that punish trust abusers in a society. Therefore, Rothstein and

Stolle argue, it is specific to these neutral institutions that social trust and institutional trust are

likely to be associated.

6

dimensions underlying the indicators of institutional trust. They named the three factors partisan

institutions (represented by parliament, political parties, and government etc.), neutral and order

institutions (the military, the police, and legal institutions), and power checking institutions (TV

and the press). Treating trust in different types of institutions as independent variables, Rothstein

and Stolle (2008) found a positive relationship between institutional trust and generalized trust.

They, however, did not investigate the effects of partisanship on trust in different types of

institutions at individual level.

For the U.S. case, Lipset and Schneider (1983) conducted factor analysis in an attempt to

discover the underlying structure of institutional trust. They were generally satisfied with a

one-factor solution, although their results hint that the media might be different from all other

political institutions. Cook and Gronke (2001) used both exploratory and confirmatory factor

analysis to reveal a much more complex structure of institutional trust. Pooling cross sections of

the General Social Survey from 1973 to 1998, Cook and Gronke found Republicans tend to have

less confidence in the media but more in other institutions, while Democrats tend to have more

confidence in the media but less in other institutions. While Cook and Gronke tested the effect of

party identification per se, Gershtenson, Ladewig, and Plane (2006) focused on identification with the party in control of an institution. Their findings show that American party identifiers tend to have more trust in Congress when their own party is in control.

These studies indicate that institutional trust is a psychological attitude that depends on both

the trusting citizen’s party identification and the type of the institution to which trust is to be

conferred. None of the works cited above, however, has investigated the effects of partisanship

on different types of institutions at the individual level. In this paper, we propose that the effect

7

institution in question is partisan or neutral in nature. Our argument is based on the social

psychological theory of cognitive dissonance to which we now turn.

Theory and Hypotheses

The literature discussed above shows that institutional trust may be influenced by various

sources, including government performance, social capital, news consumption, and party

identification. In this paper, we focus on the relationship between institutional trust and party

identification. Specifically, we follow Rothstein and Stolle (2008) in distinguishing between

partisan institutions and neutral institutions and examine their respective relationship with party

identification. We consider the media as a separate dimension concerning institutional trust but

do not investigate its determinants.

The reason that trust in partisan institutions and trust in neutral institutions are

fundamentally different, we argue, can be better illuminated by the theory of cognitive

dissonance in social psychology (Festinger 1957). When conflicting ideas or events cannot be

reconciled, people tend to alter their cognitions in order to reduce the discomfort caused by the

resulting disequilibrium. Cognitive dissonance is likely to be at work when the occurrences of

new events are compounded by the lack of information. The theory has been used to explain the

so-called issue projection in which voters’ perceptions of candidates’ issue positions are

influenced by their own positions and their evaluations of those candidates (Brody and Page

1972; Kinder 1978; Conover and Feldman 1982; Lin 2010; Lin and Lin 2012). Specifically, a

voter who supports a political candidate may perceive a proximity closer than reality between the

candidate’s position and the voter’s own position because a wider distance, even if objectively

8

who opposes a candidate may perceive a distance wider than reality between the candidate’s

position and the voter’s own position. Such subjective perceptions help balance conflicting

cognitions and reduce the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance.

We argue that cognitive dissonance is likely to be at work when a party identifier is asked to

appraise the trustworthiness of a political institution. To the extent that the institution is

associated with partisan politics, identifiers of the incumbent party are likely to perceive it as

more trustworthy than what is objectively justified by the performance of the institution.

Conversely, identifiers of the opposition party are likely to perceive the institution as less

trustworthy than justified. Overall, there is going to be a significant gap in institutional trust

between identifiers of the incumbent party and those of the opposition party, controlling for

social capital, government performance, news consumption, etc. The trust gap should manifest

itself in political institutions in general because voters tend to perceive the incumbent party as

responsible for all governmental institutions. However, we argue that, when partisan institutions

are separated from neutral institutions, the trust gap pertains mainly to partisan institutions

because the politicians in control of these institutions are unmistakably affiliated with the

political parties with which citizens may or may not identify. Conversely, we argue that the trust

gap should be less prevalent concerning neutral institutions.

In contrast with the asymmetry in the effects of party identification on trust in partisan vs.

neutral institutions, we argue that the asymmetry should not be present in the effects of social

trust. The notion of social trust is non-partisan in nature. There is no reason to expect asymmetric

effects. We expect social trust to have significant effects on both partisan and neutral institutions.

Overall, we propose the following hypotheses:

9

socioeconomic status, identifiers of the opposition parties, compared with identifiers of the

incumbent party, tend to have less trust in political institutions in general.

Hypothesis 2: Controlling for social capital, government performance, news consumption, and

socioeconomic status, identifiers of the opposition parties, compared with identifiers of the

incumbent party, tend to have less trust in partisan institutions. However, they do not necessarily

have less trust in neutral institutions.

Hypothesis 3: Ceteris Paribus, social trust tends to have positive effects on partisan institutions

and neutral institutions.

Data and Methods

To test our hypotheses, we use data from Wave 3 of the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS).

This wave of the ABS includes 11 countries, from which we chose Korea, Taiwan, Mongolia,

The Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, which we consider emerging democracies.1 Emerging democracies are particularly relevant to our investigation because, as we pointed out in the

introduction, subjective factors of institutional trust may be more prevalent in these countries.

Because these countries have different political systems and levels of democracy, we conduct our

analysis for each country respectively instead of polling all countries together in a single

analysis.2

Concerning institutional trust, the ABS asked its respondents to indicate their degree of trust

1

Wave 3 Asian Barometer Surveys were conducted in 2010-2011. More specifically, the survey times for our cases are: South Korea, May 2011; Taiwan, January-February 2010; Mongolia, April-June 2010; The Philippines, March 2010; Thailand, August-December 2010; Indonesia, May 2011.

2

A document with brief descriptions of these countries’ political systems at the time of survey is available upon request. For a list of their political parties, please see Appendix 1.3.

10

in 13 institutions, including the president (or prime minister), the courts, the national government,

political parties, parliament, civil service, the military, the police, local government, newspapers,

television, the election commission, and NGOs. For the exact wording of the items and the scale

of trust, see Appendix 1.

An important decision for our analysis is how to define partisan institutions and neutral

institutions. Conceivably, whether an institution is partisan or neutral depends on the

constitutional and political contexts of each country. Without referring to these contexts, one way

to operationalize institutional trust is to use exploratory factor analysis to sort out the institutions.

In practice, there are difficulties with this approach as the number of significant factors may be

different from country to country and those factors may not unambiguously coincide with

substantively classified partisan and neutral institutions. Furthermore, different operational

definitions from country to country are certainly not conducive to the comparison of institutional

trust in these countries. Because of these considerations, we decide to impose a consistent

operational definition for all countries. We argue that the involvement of national elections, in

which all major parties compete, is the principal criterion for partisan politics. Thus we classify

the president/prime minister, the national government, and parliament as partisan institutions and

the courts, civil service, the military, the police, and the election commission as neutral

institutions.3 For each class of institutions we construct a composite scale of trust that is simply the average trust in the institutions involved in each class. Therefore, for each country we have

two 4-point composite scales: trust in partisan institutions and trust in neutral institutions.

3

We exclude political parties and local government from our analysis. These institutions are not unique nationally, and respondents of the ABS may have been referring to different entities. We also exclude newspapers, television, and NGOs because they obviously belong to a different type of institutions that we do not explore in this paper.

11

Additionally, we construct another 4-point composite scale of general institutional trust that is

the average trust in all partisan and neutral institutions. As averages these scales retain the unit of

their component scales, with 1 indicating no trust at all and 4 indicating a great deal of trust. We

assume that these are interval scales.

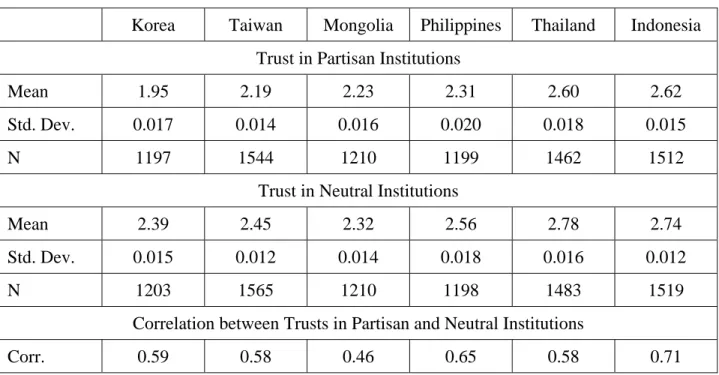

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the level of trust in partisan institutions and

neutral institutions by country. It shows that trust in both types of institutions is generally lower

in Korea, Taiwan, and Mongolia than in the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia. A more notable

pattern, however, is that trust in neutral institutions are consistently higher than trust in partisan

institutions across all six countries. Furthermore, the standard deviations associated with neutral

institutions are consistently smaller than those associated with partisan institutions, implying a

higher degree of consensus in citizens’ trust in neutral institutions. Since our theory stipulates

that trust in partisan institutions, but not trust in neutral institutions, is mitigated by partisan

politics, the divergence in both the level and the spread of trust between the two types of

institutions provides a sort of discriminant validity to our measures (Campbell and Fiske 1959).

The correlations shown in Table 1 also indicate that although the two measures are not

completely independent, the extent of overlap is at most modest.

(Table 1 about here)

To test our hypotheses, we turn to regression analyses with general institutional trust, trust

in partisan institutions, and trust in neutral institutions as our dependent variables. For

independent variables we choose party identification, civic engagement, social trust, government

12

education, and income. A brief account of these measures is given in Appendix 1.

Results and Discussion

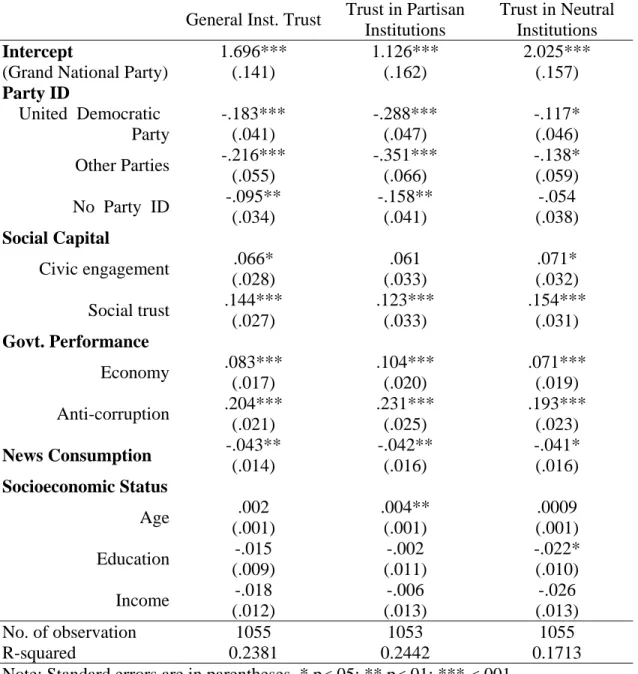

As the first columns of Tables 2.1-2.6 illustrate, our first hypothesis is supported by

empirical data. Citizens do evaluate political institutions in a subjective way in that partisanship

plays a role that biases the evaluation. More specifically, controlling for social capital,

government performance, news consumption, and socioeconomic status, identifiers of the

opposition parties and even non-identifiers, compared with identifiers of the incumbent party,

tend to have less trust in political institutions in general. This is true for all the six countries we

investigate although the evidence is not as strong for Mongolia and Indonesia as for Korea,

Taiwan, The Philippines, and Thailand. Thus, studies that ignore the effect of partisanship might

have overemphasized the significance of other, less biased factors.

(Table 3 about here)

Our second hypothesis postulates that, other things being equal, the effect of partisanship is

more significant in relation to partisan institutions than in relation to neutral institutions. As the

second and third columns of Tables 2.1-2.6 show, this hypothesis is supported for Korea, Taiwan,

The Philippines, and Thailand and not clearly so for Mongolia and Indonesia. The evidence is

strongest for The Philippines, where identifiers of the GO coalition and other parties, and even

non-identifiers, compared with identifiers of the TEAM Unity coalition, have significantly less

trust in partisan institutions, and yet partisanship has no significant effect at all in relation to trust

13

with Pan Blue identifiers, have significantly less trust in partisan institutions, but their trust level

in neutral institutions is not significantly mitigated by partisanship.

The evidence is robust, albeit not so dramatic, for Korea and Thailand. For these cases, the

effect of partisanship is not completely absent in relation to neutral institutions, but it is clearly

smaller than the corresponding effect in relation to partisan institutions. In Korea, for example,

identifiers of the United Democratic Party and other parties, compared with identifiers of the

Grand National Party, have significantly less trust in both partisan institutions and neutral

institutions. However, the effect is clearly stronger in relation to trust in partisan institutions than

to trust in neutral institutions (-.288 vs. -.117 for identifiers of the United Democratic Party and

-.351 vs. -.138 for identifiers of other parties). Rendering additional support for Hypothesis 2,

non-identifiers in Korea, compared with identifiers of the Grand National Party, exhibit

significantly less trust in partisan institutions, but their trust in neutral institutions is not

statistically different from identifiers of the Grand National Party. For the case of Thailand, the

pattern is similar. Partisanship has strong, negative effects for identifiers of the Pheu Thai Party

and other parties and for non-identifiers in relation to partisan institutions, but it has only a much

weaker effect in relation to neutral institutions that is statistically significant only for identifiers

of the Pheu Thai Party (-.695 vs. -.191).

How do we explain the fact that partisanship does exhibit some biasing effects on

supposedly neutral institutions in some East Asian countries? As we mentioned earlier, the newly

democratized countries we investigated here are not far removed from their authoritarian past.

Under an authoritarian regime, the courts, civil service, the military, and the police were more

often than not instruments for the regime to suppress its oppositions. With few exceptions,

14

regime. Even after democratization, these officials and personnel tend to retain their loyalty and

support the regime party in elections. The political affiliation is so deep-rooted that it may not be

feasible for these institutions to become really impartial even as democracy is being consolidated.

Even if it is not completely infeasible, it may be difficult for identifiers of the parties opposing

the old regime party to change their perceptions about the partiality of these institutions. All

these apply to the election commission that is relatively new in some countries, as its personnel

are likely to be drawn from civil service. It is conceivable, however, that perceptions about the

partiality or impartiality of institutions, be it neutral or partisan, can vary from institution to

institution. For this reason, we examine the effects of partisanship on individual institutions and

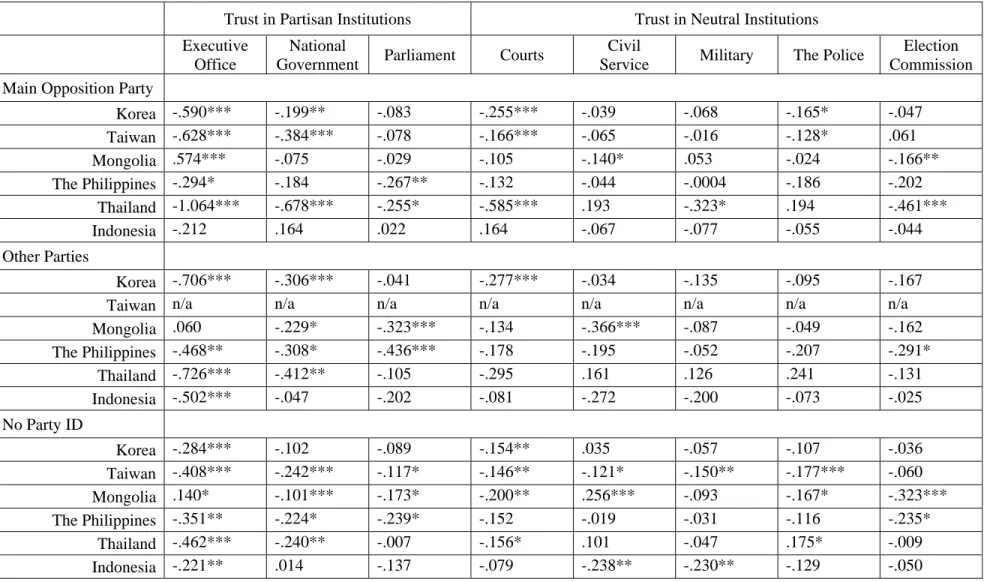

summarize relevant results in Table 3.

(Table 3 about here)

As predicted, Table 3 shows that the biasing effect of partisanship on trust is not uniform

within each class of institutions. In general, however, partisanship does have more and stronger

effects on trust in partisan institutions than on trust in neutral institutions. Except for Mongolia

and Indonesia, the executive office tends to trigger the strongest negative partisan effect on trust.

The next is the national government. As a partisan institution, the parliament is subjected to the

least partisan effect on trust, presumably because all the major parties are represented in this

institution. Among neutral institutions, partisan effects on trust are most conspicuous in the

courts, which were significantly less trusted by identifiers of the main opposition parties in

Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. The police was also perceived as partial by opposition-party

15

and Thailand. Thailand is the only country in which identifiers of the opposition party had

misgivings about the military.

These results are not surprising. The courts in Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand were considered

partial to the incumbent parties as many opposition politicians were convicted of wrongdoings,

especially corruption charges. In Thailand , a military coup ousted Prime Minister Thaksin

Shinawatra in 2006, and a military tribunal outlawed his Thai Rak Thai Party in 2007. In

Mongolia in 2008, the legislative election was mired with electoral disputes. As vote tally went

suspiciously slow, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, the Democratic Party (DP) Chairman, refused to

accept the results that would inevitably give the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP)

a clear victory. In Thailand, electoral disputes also rose after the 2007 election as the Election

Commission issued the so-called “red cards” to many MPs of the opposition party who were

suspected of vote-buying.4 Similarly, in the Philippines, accusations abounded that Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, the winning incumbent of the K-4 coalition, rigged the 2004 presidential

election, and there were many allegations of electoral irregularities in the 2007 mid-term

elections.5

Among the six countries we analyze, Mongolia and Indonesia stand out in that no

significant differences exist between identifiers of the main opposition parties and those of the

incumbent parties in terms of trust in partisan institutions. In fact, for Mongolia, identification

with DP actually has a significant positive effect (.575, p<.001) on trust in the executive office.

Why are these two cases different from others?

4

Candidates given red-cards will be banned from participating in the ensuing by-election. 5

In the Philippines case, identification with the Genuine Opposition (GO) coalition has an effect of -.202 (p=.07) on trust in the COMELEC. The effects of identification with other parties and no party ID are respectively statistically significant at the .05 level.

16

In Mongolia, although the DP lost the 2008 election that it accused of being rigged, the

party soon became a coalition partner of the MPRP’s government. Moreover, in 2009, the DP’s

Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj narrowly defeated the MPRP’s Nambaryn Enkhbayar, the incumbent, to

become the country’s President (Bulag 2009, 2010). Fears of electoral controversy did not

materialize this time as Enkhbayar conceded defeat, and power sharing apparently boosted DP

identifiers’ trust level in partisan institutions, especially the executive office.

The Indonesia case might be explained by the high popularity of the Democratic Party’s

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (commonly known as SBY), who had been President since 2004. A

musician who has three pop albums under his name, SBY’s popularity had taken a toll on the

other two major parties, GOLKAR and PDIP-Struggle (Sherlok 2009). To ease concerns over his

party’s dominance, SBY invited parties in the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) to join the

cabinet (Mietzner 2010, p. 189). That gesture effectively reduced partisan tensions.

Our third hypothesis finds overwhelming support in most cases. Social trust has significant,

positive effects on both partisan and neutral institutions in Korea, Mongolia, and Thailand. It has

significant, positive effects on neutral institutions in Taiwan and the Philippines, and it has a

significant, positive effect on partisan institutions in Indonesia. In contrast, civic engagement has

a significant, positive effect only in Korea, and only on trust in neutral institutions. These results

indicate that the relationship between social trust and institutional trust is present in new

democracies in East Asia. Between the two essential components of social capital, social trust is

apparently more relevant than civic engagement as a determinant of institutional trust. Thus,

Putnam’s postulated causation of joining and trusting is not substantiated here. Our results are

more in agreement with Rothstein and Stolle’s (2008) argument that social trust has a stronger

17

A case in point is Thailand. Thailand is the only country among our cases that went through

a dramatic political change – a military coup in 2006 – between the last two waves of ABS

survey. In ABS Wave 2 (2006), 45 percent of all Thai respondents chose the statement “Most

people can be trusted” over “You must be very careful in dealing with people” and nonresponse

options. That number decreased substantially in ABS Wave 3 (2010), to only 26 percent.

Meanwhile, membership of formal organizations in Thailand increased from 24 percent to

44percent. The conflicting trends do not square with social capital theory. We suspect that the

political conflict resulted from the 2006 coup caused the level of social trust to decline which in

turn caused trust in political institutions, including partisan institutions, the courts, the military,

and the Election Commission, to decline. The point is social trust was effectual on institutional

trust even as its level declined while civic engagement was inconsequential as its level rose.

Indonesia, again, stands out as an exception in that it is the only country of which social

trust does not have a significant effect on trust in neutral institutions. If the causal mechanism

between social trust and institutional trust is mediated through the capability of political

institutions to lower the risk of trusting, it seems that Indonesians believe that such a capability

comes more from partisan institutions than neutral institutions.

Conclusion

The profound influence of institutional trust on regime legitimacy has long been confirmed.

It is thus very important to investigate the determinants of institutional trust. Existent studies

tend to neglect the effect of partisanship and, hence, omit a crucial factor of institutional trust.

18

institutions in general and partisan and neutral institutions in particular. Empirical findings from

six emerging East Asian democracies largely support our theory and hypotheses.

Our findings shed some lights on social capital theory. The presumption that institutional

trust is generated from objective assessment of government performance does not hold true

across all types of political institutions. Since partisan institutions are formed through elections,

and parties in control of these institutions represent the interests of their constituents, trust in

these institutions is subject to partisan bias. Because of cognitive dissonance, partisanship can be

projected to citizens’ assessment of these institutions.

At first glance, the implications of our findings seem pessimistic. If institutional trust is

subject to partisan projection, there is a limit as to what a democratic government can do to

improve trust by improving governance. In recent years, the governments of some of the East

Asian countries we investigated here have suffered from dramatic decline in political trust. Our

findings raise the question as to whether such decline is due to bad governance or increasing

partisan polarization. This question is especially pertinent to emerging democracies because

partisan polarization is a lingering fact from these countries’ authoritarian past. Obviously

whichever cause it was, extensive distrust is always not conducive to a regime’s legitimacy, but

19 Appendix 1.

(1.1) ABS Items on Institutional Trust

Question Wording Q7-19 I’m going to name a number of institutions. For each one, please tell me how much

trust do you have in them? Is it a great deal of trust, quite a lot of trust, not very much trust, or none at all?

Q7 The president (for presidential system) or Prime Minister (for parliamentary system)

Q8 The courts Q9 The national government Q10 Political parties Q11 Parliament Q12 Civil service

Q13 The military (or armed forces) Q14 The police

Q15 Local government Q16 Newspapers Q17 Television

Q18 The election commission [specify institution by name]

Q 19 NGOs

Note: All the questions have the same scale but the scale is reversed in our analysis such that 1=none at all, 2= not very much trust, 3=quite a lot of trust, 4=a great deal of trust.

20

(1.2) Items used as Independent and Control Variables

Item Question Q47 Partisanship: Among the political parties listed here, which party if any do you feel

closest to? Partisanship is recoded as dummy variables. The details of coding scheme are provided in 1.3.

Q20-22 Civic engagement: membership in formal groups. Civic engagement is recoded as 0. “Non-member” and 1. “Member(s)”.

Q23 Social trust: it is recoded as 0. “You must be careful in dealing with people, and 1. “Most people can be trusted”.

Q3 Government performance-economy: What do you think will be the state of our country’s economic condition a few years from now? The variable is recoded as 1. “Much worse”, 2. “A little worse”, 3. “About the same”, 4. “A little better”, and 5. “Much better”.

Q118 Government performance-anti-corruption: In your opinion, is the government working to crack down on corruption and root out bribery? The variable is recoded as 1. “Doing nothing”, 2. “It is not doing much”, 3. “It is doing something”, and 4. “It is doing its best”.

Q44 News consumption: How often do you follow news about politics and

government? The variable is recoded as 1. “Practically never”, 2. “Not even once a week”, 3. “Once or twice a week”, 4. “Several times a week”, and 5. “Everyday”.

SE3a Age

SE5 Highest level of education

21 (1.3) Coding Scheme of Partisanship

Country Coding

Korea

Governing party: Grand National Party

Main opposition party: United Democratic Party

Other parties: identifiers with parties other than the governing party and the main opposition party.

No party ID: respondents who are not close to any party. Taiwan

Governing party: Pan Blue parties, including KMT, PFP, and the New Party Main opposition party: Pan Green parties, including DPP and TSU. No party ID: respondents who are not close to any party.

Mongolia

Governing party: MPRP

Main opposition party: Democratic Party

Other parties: identifiers with parties other than the governing party and the main opposition party.

No party ID: respondents who are not close to any party.

The Philippines

Governing party: TEAM Unity, including LAKAS, KAMPI, and LDP. Main opposition party: Genuine Opposition (GO), including LP, PMP, and

PDP-LABAN.

Other parties: identifiers with parties other than the governing party and the main opposition party.

No Party ID: respondents who are not close to any party.

Thailand

Governing Party: Democrat Party Main opposition party: Pheu Thai Party

Other parties: identifiers with parties other than the governing party and the main opposition party.

No Party ID: respondents who are not close to any party.

Indonesia

Governing Party: Democratic Party Main opposition party 1: GOLKAR Main opposition party2: PDIP-Struggle Religious party: PKS, PAN, and PKB

Other parties: identifiers with parties other than the governing party, the main opposition parties, and religious parties.

22 References

Brody, Richard A., and Benjamin I. Page. 1972. “Comment: The Assesment of Policy Voting.” American Political Science Review 66(2):450-458.

Bulag, Uradyn E. 2010. “Mongolia in 2009: From Landlocked to Land-linked Cosmopolitan.” Asian Survey 50(1): 97-103

Bulag, Uradyn E. 2009. “Mongolia in 2008: From Mongolia to Mine-golia.” Asian Survey 49(1): 129-134.

Campbell, Donald T. and Donald W. Fiske. 1959. “Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethods Matrix.” Psychological Bulletin 56(2):81-105.

Conover, Pamela J., and Stanley Feldman. 1982. “Projection and the Perception of Candidates’ Issue Positions.” The Western Political Quarterly 35(2):228-244.

Cook, T. E. and P. Gronke. 2001. “The Dimensions of Institutional Trust: How Distinct is Public Confidence in the Media.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Deutsch, Morton. 1958. “Trust and Suspicion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 2(4):265-279.

Damico, Alfonso J., M. Margaret Conway, and Sandra Bowman Damico. 2000. “Patterns of Political Trust and Mistrust: Three Moments in the Lives of Democratic Citizens.” Polity 32(3):377-400.

Festinger, Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Evanston, Ill.: Row, Peterson.

Gershtenson, Joe, Jeff Ladewig, and Dennis L. Plane. 2006. “Parties, Institutional Control, and Trust in Government.” Social Science Quarterly 87(4):882-902.

Hetherington, Marc J. 1998. “The Political Relevance of Political Trust.” American Political Science Review 94(4):791-808.

Kim, Ji-Young. 2005. “‘Bowling Together’ Isn't a Cure-All: The Relationship between Social Capital and Political Trust in South Korea.” International Political Science Review 26(2):193-213.

Kinder, Donald R. 1978. “Political Person Perception: The Asymmetrical Influence of Sentiment and Choice on Perceptions of Presidential Candidates.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36(8):859-71.

Lin, Tse-min, and Tzu-Hsin Lin. 2012. “Party Identification and the Perception of Candidates’ Issue Positions.” Prepared for presentation at the International Conference on the Maturing of

23

Taiwan Democracy: Findings and Insights from the 2012 TEDS Survey. November 3-4, 2012, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Lin, Tzu-Hsin. 2010. “Voters’ Perception of Candidate Positions: The Unification-Independence Issue in Taiwan’s 2004 and 2008 Presidential Elections.” Master’s Thesis. Department of Political Science, Soochow University.

Lipset, S. M. and W. Schneider. 1983. “The Decline of Confidence in American Institutions.” Political Science Quarterly 98(3):379-402.

Mietzner, M. 2010. “Indonesia in 2009: Electoral Contestation and Economic Resilience." Asian Survey 50(1):185-194.

Newton, K. and P. Norris. 2000. “Confidence in Public Institutions.” In Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries, ed. Susan Pharr and Robert Putnam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 52-73.

Orren, G. 1997. “Fall from Grace: The Publics Loss of Faith in Government.” In Why People Don’t Trust Government, ed. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Philip D. Zelikow, and David C. King. Cambridge: Harvard University Press pp. 77-107.

Putnam, R. D. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rothstein, Bo and Dietlind Stolle. 2008. “The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust.” Comparative Politics 40(4):441-459.

Sherlock, Stephen. 2009. Parties and Elections in Indonesia 2009: The Consolidation of Democracy. Research Paper 35 Parliament of Australia.

Warren, Mark E. 1999. “Introduction.” In Democracy and Trust, ed. Mark E. Warren. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp. 1-21.

24 Table 1. Institutional Trust, by Country

Korea Taiwan Mongolia Philippines Thailand Indonesia Trust in Partisan Institutions

Mean 1.95 2.19 2.23 2.31 2.60 2.62

Std. Dev. 0.017 0.014 0.016 0.020 0.018 0.015

N 1197 1544 1210 1199 1462 1512

Trust in Neutral Institutions

Mean 2.39 2.45 2.32 2.56 2.78 2.74

Std. Dev. 0.015 0.012 0.014 0.018 0.016 0.012

N 1203 1565 1210 1198 1483 1519

Correlation between Trusts in Partisan and Neutral Institutions

25 Table 2. Regression Analysis of Institutional Trust (2.1) Korea

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions

Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept

(Grand National Party)

1.696*** (.141) 1.126*** (.162) 2.025*** (.157) Party ID United Democratic Party -.183*** (.041) -.288*** (.047) -.117* (.046) Other Parties -.216*** (.055) -.351*** (.066) -.138* (.059) No Party ID -.095** (.034) -.158** (.041) -.054 (.038) Social Capital Civic engagement .066* (.028) .061 (.033) .071* (.032) Social trust .144*** (.027) .123*** (.033) .154*** (.031) Govt. Performance Economy .083*** (.017) .104*** (.020) .071*** (.019) Anti-corruption .204*** (.021) .231*** (.025) .193*** (.023) News Consumption -.043** (.014) -.042** (.016) -.041* (.016) Socioeconomic Status Age .002 (.001) .004** (.001) .0009 (.001) Education -.015 (.009) -.002 (.011) -.022* (.010) Income -.018 (.012) -.006 (.013) -.026 (.013) No. of observation 1055 1053 1055 R-squared 0.2381 0.2442 0.1713 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

26 (2.2) Taiwan

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions

Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept (Pan Blue) 1.731***

(.109) 1.600*** (.129) 1.821*** (.120) Party ID Pan Green -.178*** (.030) -.363*** (.037) -.065 (.033) No Party ID -.181*** (.028) -.266*** (.034) -.131*** (.032) Social Capital Civic engagement .011 (.025) -.029 (.030) .037 (.028) Social trust .067** (.025) .049 (.029) .075** (.027) Govt. Performance Economy .077*** (.013) .124*** (.016) .052*** (.014) Anti-corruption .181*** (.017) .196*** (.021) .170*** (.019) News Consumption -.006 (.008) -.014 (.009) -.00009 (.009) Socioeconomic Status Age .002* (.001) .0008 (.001) .002* (.001) Education -.009 (.008) -.009 (.010) -.012 (.009) Income -.015 (.010) -.020 (.012) -.010 (.012) No. of observation 1247 1236 1247 R-squared 0.2322 0.2907 0.1460 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

27 (2.3) Mongolia

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept (MPRP) 1.906*** (.099) 1.557*** (.134) 2.122*** (.104) Party ID Democratic Party .013 (.033) .161 (.042) -.076* (.037) Other Parties -.158** (.050) -.164* (.069) -.156** (.056) No Party ID -.148*** (.037) -.045 (.049) -.212*** (.041) Social Capital Civic engagement .024 (.029) .039 (.041) .015 (.030) Social trust .155*** (.037) .225*** (.053) .113** (.038) Govt. Performance Economy .089*** (.016) .106*** (.022) .078*** (.018) Anti-corruption .094*** (.017) .110*** (.024) .083*** (.018) News Consumption .017 (.013) .026 (.018) .011 (.013) Socioeconomic Status Age -.002* (.001) .0001 (.001) -.003** (.001) Education -.014** (.005) -.012 (.007) -.015** (.006) Income -.017 (.012) -.032 (.016) -.008 (.013) No. of observation 1114 1114 1114 R-squared 0.1378 0.1353 0.0957 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

28 (2.4) The Philippines

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept (TEAM Unity) 2.450 (.156) 2.316*** (.183) 2.532*** (.168) Party ID Genuine Opposition2 -.162* (.071) -.249** (.084) -.110 (.076) Other Parties -.262** (.086) -.401*** (.101) -.179 (.091) No Party ID -.170* (.069) -.273** (.080) -.107 (.074) Social Capital Civic engagement .039 (.041) .018 (.049) .053 (.048) Social trust .233** (.068) .121 (.077) .309*** (.076) Govt. Performance Economy .086*** (.018) .117*** (.021) .066** (.019) Anti-corruption .129*** (.023) .146*** (.027) .119*** (.025) News Consumption .028 (.016) .015 (.020) .037* (.018) Socioeconomic Status Age -.005** (.001) -.004** (.001) -.006*** (.001) Education -.038** (.010) -.038** (.011) -.039*** (.011) Income -.032 (.021) -.053* (.025) -.020 (.022) No. of observation 1010 1010 1009 R-squared 0.1436 0.1415 0.1125 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

29 (2.5) Thailand

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept (Democrat Party) 1.957*** (.186) 1.699*** (.217) 2.133*** (.201) Party ID

Pheu Thai Party -.384*** (.068) -.695*** (.085) -.191* (.076) Other Parties -.137 (.116) -.395** (.131) .011 (.121) No Party ID -.089* (.042) -.244*** (.056) .005 (.048) Social Capital Civic engagement .039 (.041) -.022 (.050) .077 (.045) Social trust .100* (.042) .119* (.052) .093* (.046) Govt. Performance Economy .195*** (.024) .238*** (.028) .166*** (.026) Anti-corruption .179*** (.023) .225*** (.028) .157*** (.025) News Consumption .008 (.019) -5.07e-06 (.023) .012 (.021) Socioeconomic Status Age -.001 (.001) -.001 (.002) -.001 (.001) Education -.037*** (.010) -.034** (.012) -.040** (.011) Income -.025 (.019) .008 (.023) -.044 (.021) No. of observation 759 750 759 R-squared 0.2942 0.3533 0.1963 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

30 (2.6) Indonesia

General Inst. Trust Trust in Partisan Institutions Trust in Neutral Institutions Intercept (Democratic Party) 2.198*** (.174) 2.023*** (.203) 2.287** (.192) Party ID GOLKAR .001 (.074) -.007 (.094) .003 (.072) PDIP-Struggle -.084 (.079) -.066 (.114) -.096 (.078) Religious Party1 .002 (.133) .055 (.192) .012 (.106) Other Parties -.178* (.083) -.250* (.114) -.136 (.079) No Party ID -.142* (.057) -.116 (.070) -.153* (.060) Social Capital Civic engagement -.013 (.070) .002 (.093) -.012 (.084) Social trust .130** (.040) .205*** (.042) .084 (.054) Govt. Performance Economy .129*** (.022) .162*** (.024) .110*** (.025) Anti-corruption .129*** (.022) .111*** (.029) .108*** (.026) News Consumption -.015 (.012) -.016 (.015) -.012 (.015) Socioeconomic Status Age .001 (.001) .0001 (.001) .001 (.001) Education -.003 (.009) -.014 (.012) .0005 (.009) Income -.061*** (.015) -.047* (.020) -.069*** (.017) No. of observation 1133 1131 1133 R-squared 0.1719 0.1614 0.1384 Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.

31

Table 3. Summary of Regression Analyses of Trust in Individual Institutions

Trust in Partisan Institutions Trust in Neutral Institutions

Executive Office

National

Government Parliament Courts

Civil

Service Military The Police

Election Commission Main Opposition Party

Korea -.590*** -.199** -.083 -.255*** -.039 -.068 -.165* -.047 Taiwan -.628*** -.384*** -.078 -.166*** -.065 -.016 -.128* .061 Mongolia .574*** -.075 -.029 -.105 -.140* .053 -.024 -.166** The Philippines -.294* -.184 -.267** -.132 -.044 -.0004 -.186 -.202 Thailand -1.064*** -.678*** -.255* -.585*** .193 -.323* .194 -.461*** Indonesia -.212 .164 .022 .164 -.067 -.077 -.055 -.044 Other Parties Korea -.706*** -.306*** -.041 -.277*** -.034 -.135 -.095 -.167

Taiwan n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

Mongolia .060 -.229* -.323*** -.134 -.366*** -.087 -.049 -.162 The Philippines -.468** -.308* -.436*** -.178 -.195 -.052 -.207 -.291* Thailand -.726*** -.412** -.105 -.295 .161 .126 .241 -.131 Indonesia -.502*** -.047 -.202 -.081 -.272 -.200 -.073 -.025 No Party ID Korea -.284*** -.102 -.089 -.154** .035 -.057 -.107 -.036 Taiwan -.408*** -.242*** -.117* -.146** -.121* -.150** -.177*** -.060 Mongolia .140* -.101*** -.173* -.200** .256*** -.093 -.167* -.323*** The Philippines -.351** -.224* -.239* -.152 -.019 -.031 -.116 -.235* Thailand -.462*** -.240** -.007 -.156* .101 -.047 .175* -.009 Indonesia -.221** .014 -.137 -.079 -.238** -.230** -.129 -.050

Note: Only coefficients associated with party ID are shown; those associated with other variables are omitted. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** <.001.