行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期末報告

以社會學觀點探究英語學習者之部落格寫作經驗

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 101-2410-H-004-165- 執 行 期 間 : 101 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學外文中心 計 畫 主 持 人 : 陳彩虹 計畫參與人員: 大專生-兼任助理人員:陳柏安 大專生-兼任助理人員:徐珮芳 大專生-兼任助理人員:劉虹均 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 102 年 10 月 30 日

中 文 摘 要 : 這個研究計劃探索台灣一所大學的學生撰寫英語部落格的經 驗差異,目的是要了解造成這些差異的原因。本研究分兩階 段進行,第一階段中,研究者於一個大學英文課實施部落格 計畫,研究重點在對學生的部落格寫作經驗與其看法做系統 式的描繪與比較,結果顯示學生對該部落格計畫的評價與他 們的學習特質有密切關係。在本研究第二階段中,研究者於 三個大學英文必修課班級實施類似的部落格計畫,一方面是 查驗當學生樣本較大,且課程性質不同時,研究結果是否相 同;另一方面則是探究學生的部落格寫作經驗是否會因他們 的主修與英文程度及信心而有所差別。撰寫這份報告時,第 二階段所蒐集到資料仍在分析中,因此這份報告涵蓋內容為 第一階段發現與第二階段的部分初步結果。 中文關鍵詞: 部落格, 學生差異, 英語為外語

英 文 摘 要 : This study investigated EFL learners` differing blogging experiences at a university in Taiwan, with a view to understanding the factors underlying the differences. The study was implemented in two phases. In the first phase, a blog project was conducted in an elective college English class. The aim was to systemically characterize and compare

learners` perceptions and experiences of L2

blogging. The results indicated that participants' blogging experiences were closely related to their educational dispositions. In the second phase of the study, a similar blog project was conducted in three compulsory college English classes to examine whether the results were the same with a larger sample size and courses of a different nature. Another purpose of this phase was to investigate whether

learners` majors, their English proficiency, and self-confidence in their language ability, had an impact on their writing experience. At the time of writing, data analysis for phase two of the study was still underway, so this report presents the findings from phase one and some preliminary results from phase two.

1

A sociological perspective on empowering EFL learners through a blog project

INTRODUCTIONBecause of their potentials to enhance self-expression, interactivity and collaboration, Web 2.0 technologies have continued to excite educators worldwide. Among these participatory technologies, so far, blogs have been the most commonly used in education. Richardson (2010) argued that blogs have the capacity to: 1) expand learning beyond the classroom walls; 2) archive the learning process, thereby allowing reflection and metacognitive analysis; 3) support different learning styles; 4) help develop expertise in a particular subject; and 5) teach the new literacies that learners need to function in an information society, including critical reading and thinking (pp.26-27). Two defining characteristics of blogs distinguish them from other asynchronous communication tools such as emails and discussion forums. One is that blogs are intended to be viewable to the large audience on the Internet, and the other is that blogs are owned by individuals—that is, bloggers have control of their own blogs in terms of the content and the presentation of their blogs (Carney, 2009; Thorne & Payne, 2005). Both these characteristics have their pedagogical implications. For example, when used in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) education, learners may be more careful about their language because of the potential audience beyond the classroom. With the freedom to make choices for their blogs, learners may develop a sense of ownership and thus become more motivated.

Researchers have examined blogs’ potential to provide language skill practice, most typically in writing (Bloch, 2007), and recently also in speaking (through voice blogging) (Huang, 2013; Sun, 2009). Blogs have also been used to sharpen L2 learners’ metacognitive skills, such as their abilities to conduct autonomous (Bhattacharya & Chauhan, 2010), reflective (Absalom & De Saint Léger, 2011; Murray & Hourigan, 2008) and collaborative learning (Miceli, Murray & Kennedy, 2010; Mompean, 2010). Finally, an increasing number of studies have explored how blogs assist L2 learners in developing intercultural competence (Comas-Quinna, Mardomingoa & Valentinea, 2009; Melo-Pfeifer, 2013). Many of the teaching designs involved in this past research were inspired by constructivism, which was likely because the individual ownership of blogs (hence, learner

empowerment), coupled with their participatory nature (hence, learner interaction and collaboration) has lent themselves to this form of pedagogy. The studies have generally reported attaining the target pedagogic goals, with qualitative data indicating favorable learning experiences and quantitative data showing language gains or a satisfying participation rate.

Despite the overall positive results, a small number of investigations have reported

unfavourable learner experiences and perceptions. For example, some learners were found to be reluctant to publicize their work online for fear of criticism (Alm, 2009); not motivated by blog tasks because they were not interested in the blogging topics and viewed the tasks as extra

homework (Vurdien, 2013); or felt peer comments lacked variety and depth hence disengaging (Lee, 2010). While these perceptions were not representative of the participants in the studies, they

2

indicate that the frequently claimed educational benefit of blogs in motivating and empowering learners through personalizing learning, did not materialize for all learners. Indisputably, all learning tools or environments are not amenable to every learner; however, considering that previous research on L2 blogging has paid little attention to discrepancies between learners’ experiences, this study aimed to address this gap in the literature by exploring how EFL blogging environments underpinned by constructivist pedagogy may empower some learners while

disengaging others. Specifically, the study examined EFL learners’ blogging experiences at a university in Taiwan, with a view to understanding the factors underlying the differences in their experiences.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This investigation drew on Specialization Codes of Legitimation (2007, 2014) as its theoretical framework. Specialization Codes of Legitimation is one dimension of Maton’s Legitimation Code Theory (LCT). LCT describes education as comprising fields of struggle where actors’ beliefs and practices represent competing claims to legitimacy; that is, actors within a field are constantly “striving to attain more of that which defines achievement and to shape what is defined as

achievement to match their own practices” (Maton, 2014, p.17). The dimension of Specialization Codes of Legitimation, abbreviated as LCT(Specialization), is then a means to understanding the dominant basis of achievement, or what makes actors and practices special and worthy of

distinction, in a field. Underpinning LCT(Specialization) is the notion that every practice, belief or knowledge claim, is about or oriented towards something (i.e., its object) and by someone (i.e., its subject). Educational contexts or practices, for example, embody messages as to both what is valid to know and how (their object), and also who is an ideal actor (their subject). When applied to L2 learning, the “what” refers to the language skills to be learned and the “how” denotes procedures through which these skills are learned, and the “who” is the language learner. According to Maton, when analyzing educational contexts or practices, one can then distinguish two kinds of relations: relations between practices and their object, called “epistemic relations” (ER), and relations between practices and their subject, called “social relations” (SR).

Each of these relations may be relatively strongly (+) or weakly (-) emphasized in a practice. The relative strength of the two relations then allows the practice to be categorized with a

“specialization code” (ER+/-, SR+/-). The four possible specialization codes, annotated with their referents in L2 learning contexts (either language skills or language learners), are:

knowledge code (ER+, SR-), where possession of specialized knowledge (i.e., language

skills) are emphasized as the basis of achievement, and the attributes of actors (i.e., language learners) are downplayed;

knower code (ER-, SR+), where specialized knowledge (i.e., language skills) are less

significant and instead the attributes of actors (i.e., language learners) are emphasized as measures of achievement;

3

elite code (ER+, SR+), where legitimacy is based on both possessing specialized

knowledge and being the right kind of knower; and,

relativist code (ER-, SR-), where legitimacy is ostensibly determined by neither

specialized knowledge nor knower attributes.

METHODOLOGY

The study was implemented in two phases. In the first phase, a blog project was conducted in an elective college English class to explore the differences in learners’ perceptions and experiences of L2 blogging. The research questions guiding this phase were: 1) What characterizes the learners who experienced an constructivist-inspired project positively, and the learners who perceived such as project less positively?, and 2) How do specialization codes help explain the differences?

In the second phase of the study, a similar blog project was conducted in three compulsory college English classes to examine whether the results were the same with a larger sample size and courses of a different nature. Another purpose of this phase was to investigate whether learners’ majors, their English proficiency, and self-confidence in their language ability, have an impact on their writing experience.

Project design

In the blog project involved in phase 1, students wrote personal blogs of their chosen topics. Each week, they were required to write one post on their own blog, and to respond to two of their classmates’ blogs, one assigned by the instructor, and the other of their own choosing. Other learning activities included: reading weekly language correction notes provided by the instructor, a self-editing activity, and a meet-your-partners activity. In the second phase, a similar teaching design was implemented, except that there was no meet-your-partner activity, and that language corrections were provided by teaching assistants rather than by the instructor.

Participants

Participants were all non-English major undergraduates. Phase 1 participants (n = 33) were second- and third-year students enrolled in an elective college English class. They were from different fields of study, including social sciences (n = 12), foreign languages (n = 6), commerce (n = 5), law (n = 4), communication (n = 2), sciences (n = 2), liberal arts (n = 1), and international affairs (n = 1). Phase 2 participants were all freshmen enrolled in three different compulsory college English classes: Class X (n = 28), Class Y (n = 31), and Class Z (n = 34). Students in Class X were all studying in commerce. Class Y consisted of law (n = 23) and education (n = 8) majors, and Class Z comprised foreign languages (n = 17) and communication (n = 17) majors.

Data collection

4

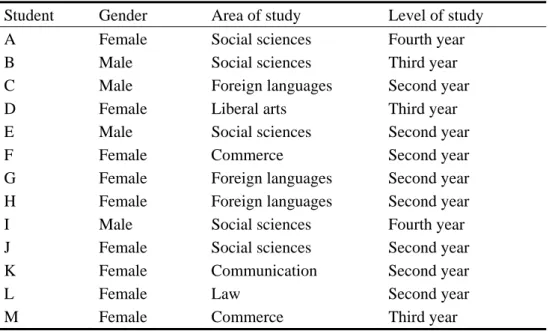

was administered at the end of the project, which asked learners to rate the learning activities on a scale of 0 to 5, and to give reasons for their ratings in an open-ended fashion. To delve into individual students’ learning experiences, one-on-one interviews were conducted with 13 of the students after the project was finished. Table 1 outlines relevant information about these

interviewees. During the interviews, students were asked to describe how they approached the tasks; their perceived benefits and challenges involved in each task; and their evaluation of their learning outcomes.

Table 1. Relevant Information about the Interviewees in phase 1 Student Gender Area of study Level of study

A Female Social sciences Fourth year

B Male Social sciences Third year

C Male Foreign languages Second year

D Female Liberal arts Third year

E Male Social sciences Second year

F Female Commerce Second year

G Female Foreign languages Second year

H Female Foreign languages Second year

I Male Social sciences Fourth year

J Female Social sciences Second year

K Female Communication Second year

L Female Law Second year

M Female Commerce Third year

A second questionnaire was developed based on the findings from phase 1, which aimed to examine the relationships between learners’ learning orientations and their satisfaction with the blog project in a quantitative way. The instrument contained 17 items assigned to four scales, namely,

Satisfaction with the Project, Preference for Knowledge Code Activities, Preference for Knower Code Activities, and Preference for Interaction. Sample items were “I feel a sense of achievement when reading my blog now” (Satisfaction with the Project), “When I read others’ blogs, I paid attention to their English” (Preference for Knowledge Code Activities), “I enjoyed writing about the same subject in my blog” (Preference for Knower Code Activities), and “I always looked forward to reading others’ blogs” (Preference for Interaction). Respondents were asked to express how much they agreed or disagreed with a particular statement, on a 5-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. They were also asked to provide their English language test results for both the General Scholastic Ability Test (GSAT) and the Advanced Subjects Test (AST), as well as to rate their confidence in their own English language ability on a scale of 1 (I have no confidence at all) to 5 (I am very confident).

In phase 2, the questionnaire was administered to all participants at the end of the project. After the project was completed, individual interviews were conducted with 28 of the participants,

5

and 9 from Class Z (6 foreign languages and 3 journalism majors). During the interviews, students were asked to elaborate on their responses to the questionnaire, and to discuss their experiences of participating in the project. All interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data analysis

Quantitative data collected in the study was analyzed using SPSS. Qualitative data was analyzed through the lens of LCT(Specialization), using an analytical framework for the concepts of epistemic relations and social relations (Table 2).

6

Table 2. Analytical Framework for Epistemic and Social Relations in this Study

Epistemic relations (ER) Social relations (SR) Concept manifested as emphasis on: Indicators for deciding ER strength Example quotes of indicators from empirical data Concept manifested as emphasis on: Indicators for deciding SR strength Example quotes of indicators from empirical data

language skills ER+ Language skills are emphasized as determining form of legitimate educational knowledge.

When reading others’ blogs, I learned words and phrases that were new to me, and I could see the errors they made, and learned from that. personal knowledge and experience SR+ Personal experience and opinions are viewed as legitimate knowledge in the language learning context.

You may get to know different people through your blog. You may hear about new

perspectives, even those from people in different countries. ER- Language skills are

downplayed as less important in defining legitimate educational knowledge.

I wouldn’t be put off by language errors

someone made on their blog. I normally

focused on reading the content.

SR- Personal experience and opinions are

downplayed and distinguished from legitimate knowledge in the language learning context.

Except for those who know me personally, who would care about my life or what I think?

7 RESULTS

At the time of writing, data analysis for the second phase was still in progress, so this section presents findings from phase 1 and some preliminary results from phase 2.

Pedagogical intentions behind the project

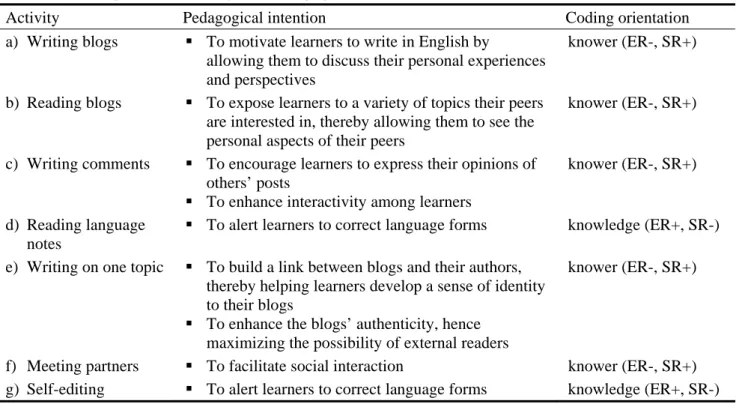

Using the analytical framework to examine the pedagogical design of the blog projects involved in both phases, it was found that the design was underpinned by a knower code. Table 3 outlines the pedagogical intention behind each of the learning activities as was communicated to students by the instructor, and the coding orientation of each activity according to the analytical framework:

Table 3. Coding Orientations of the Pedagogical Intentions

Activity Pedagogical intention Coding orientation

a) Writing blogs To motivate learners to write in English by

allowing them to discuss their personal experiences and perspectives

knower (ER-, SR+)

b) Reading blogs To expose learners to a variety of topics their peers are interested in, thereby allowing them to see the personal aspects of their peers

knower (ER-, SR+)

c) Writing comments To encourage learners to express their opinions of others’ posts

To enhance interactivity among learners

knower (ER-, SR+)

d) Reading language notes

To alert learners to correct language forms knowledge (ER+, SR-) e) Writing on one topic To build a link between blogs and their authors,

thereby helping learners develop a sense of identity to their blogs

To enhance the blogs’ authenticity, hence maximizing the possibility of external readers

knower (ER-, SR+)

f) Meeting partners To facilitate social interaction knower (ER-, SR+) g) Self-editing To alert learners to correct language forms knowledge (ER+, SR-)

Findings based on interview data collected in phase 1

Among the thirteen students interviewed in phase one, five (students A to E) reported receiving great benefits from the project, three (F to H) indicated some benefits, and the other five (I to M) said the project did not have much positive impact on their English learning. To tease out the factors separating positive and negative EFL blogging experiences, the following results concentrate on comparing the characteristics of the satisfied learners (A to E, classified as “group 1”), and the less-satisfied learners (I to M, classified as “group 2”).

Characteristics of satisfied learners

A strong theme running through the interview data was that group 1 students had a lot to say about their topics. Several of them stated that they had sufficient content to add to their blogs if the project were to continue for another semester. For example, student E, who wrote about baseball,

8 commented:

I have plenty of things to write. There were about ten games being played every day… I normally watched my favorite teams, but I also paid attention to special incidents about other teams. Without this blog, I would’ve been chatting with my friends or people on the Internet about the games anyway.

As indicated in the quote, the content of student E’s blog was an important part of his everyday life. In addition, he and the other students in this group considered themselves to have a degree of expertise in their topics, and some also demonstrated the intention to educate readers about their topics. For example, the following statement by student B, whose blog was about rock bands in the 70s and 80s, shows that he claimed expertise in his topic based on his experience of being a

guitarist. He felt the experience entitled him to decide for his readers worthwhile information to learn about the bands:

The musicians I wrote about are all my favorite and I know a lot about them. I know what is so legendary about them and what is worth writing. Based on my knowledge, I decided which interesting parts I wanted to include in my post…. Because I have played the guitar for a long time, I don’t want to introduce some mainstream musicians. That kind of information is not interesting. (Italics added)

The remark was echoed by student A, who wrote about flamenco. Albeit in a less assertive tone, she noted that being a flamenco dancer, she was capable of selecting key information about the dance and redescribing it in a way that made flamenco more accessible to her readers:

I find online information about flamenco overwhelmingly long, and even as a dancer myself, I can’t always grasp the point immediately. I hope that after reading the brief and simple descriptions of flamenco on my blog, my classmates would have a basic understanding of the dance.

On occasion, some students in this group had few peer comments. However, they were not disheartened by this, apparently largely because of the confidence they had in their knowledge of their topics. Three (B, C, E) felt that it was likely caused by their classmates not knowing enough about the topic to write a comment. Many (A, B, C, E) also added that they considered writing their blogs a worthwhile experience even with a lack of peer comments because they were able to

document their feelings and thoughts about something they were devoted to. The ability to write about their devotion in a foreign language had a significant meaning for this group. One said with noticeable pride, “Having the capability to keep an English blog about animation is a manifestation

9

of my passion for it” (C). To another student, this capability also brought about a sense of ownership of her work, as suggested in this remark:

The feeling that I have organized my understanding of Flamenco by myself gave me a great sense of achievement. I used to only listen to other people talking about it, or read about it on the Internet. This semester I felt I had documented my knowledge about the dance. (A)

Another characteristic this group had in common was their conscious effort to build a self-image through their blogs, which indicated that they had readers in mind while writing. For example, student B said:

Readers may be judging who I am by what I wrote. They may be evaluating whether I’m really a guitarist myself, or simply someone who listens to rock music. Who knows who will be reading my blog?

The above quote also showed the student was considering the possibility of having an audience outside class. Audience awareness led several students (A, C, E) to refraining from using jargon and information that required insider knowledge to decipher. For example, student E stated, “if I said a pitcher was injured because of a particular way he threw the ball, I think none of my classmates would understand me.” An even stronger audience awareness was observed in student B, who started to use some technical terms in the mid-semester, after he shared his blog with his guitarist friends outside class. “They wouldn’t want to read detailed explanations of the simple stuff,” he said, but adding that in order not to lose his non-guitarist readers in class, he attached Chinese translation to those terms.

While most students in this group were happy to receive feedback on their English, most of them said they did not see a detailed correction of their English as necessary. Moreover, although they all revised their sentences after reading the teacher’s suggestions, only one stated that he read the teacher’s language suggestions for other students. Many also mentioned that when reading their classmates’ blogs, they did not pay much attention to their classmates’ English. When asked if they felt their English had improved because of the project, all of them gave an affirmative answer. In their explanation, as the project proceeded, they were able to write more in a shorter time. Student D described her observation in this comment:

When writing the third or fourth post, I was quite satisfied with my writing. I felt I had a better sense of English. I mean, I didn’t get stuck at as many places as before. Compared with my previous posts, I could feel I wrote much faster.

She added that she had never experienced this kind of progress before because in the past, she had only written for exams. When writing for that purpose, she noted, “I worried about a lot of things,

10

such as structure and grammar, and I concentrated on inserting fancy vocabulary and sentence patterns into my writing to impress the marker.” Another student said that in her later posts, she found she was able to “skip the step of translating her thoughts from Chinese to English” (D).

Characteristics of less-satisfied learners

Like their group 1 counterparts, group 2 exhibited shared characteristics, although most of these were in direct contrast to those of group 1. The most salient characteristic was that, group 2 did not demonstrate passion or lasting commitment to their blog topics. In fact, all of them experienced difficulty focusing on their topics. One discussed the stress of having nothing to say about her topic:

The night before the due date, I would start worrying there was nothing new I could say about this singer. I chose her as my topic because I happened to be listening to her latest album at the time. I didn’t plan what I would write about her, so I became a bit anxious. I felt I was running out of ideas all the time. (K)

Another gave up on her initial topic because she was not willing to dedicate time to researching it:

I had wanted to write about music, and I spent a lot of time looking for information in the first two weeks. But then I found it took too much time, so I switched to writing about miscellaneous things that happened in my daily life. (M)

In terms of audience awareness, two students (K, L) in this group showed that they were conscious of the larger audience on the Internet, but the awareness had a negative impact on their writing. Contrary to their group 1 peers striving to construct a positive image because of the awareness, the two students detached themselves from their writing by avoiding disclosing their opinions, as indicated in this quote:

I wouldn’t say what was on my mind that might sound too critical. I might touch on the issue but I wouldn’t go into too much depth…. People may get upset, and I worry about the

consequences. I mean, some people may leave nasty messages on my blog. I don’t like that. (L)

The rest of the group said that it had never occurred to them that people outside class might read their blogs even though the teacher had mentioned the possibility. Typical comments provided by these students were, “Who would read my blog? It’s just an assignment; it’s not like I have written something that’s a big deal” (I) and “Except for those who know me personally, who would care about my life or what I think?” (M). These statements also suggested that, unlike group 1, the students did not think their blogs would offer valuable information to others. Neither did they share Group 1’s sense of mission to introduce what they knew about their topics to their readers. This observation was confirmed when another two students (I, J), who wrote about health tips and

11

volunteer work experience, gave a lukewarm response to the question of whether they would feel pleased if their blogs helped other people learn about their topics. Regardless of the relatively large number of responses some of his posts had attracted, student I noted, “It gave me a chance to practice English, and that’s all.”

In contrast to their lack of enthusiasm about their writing content, this group expressed great concern about their language improvement. The data indicated that they did not find participating in the project a satisfying experience because they felt it did not help them improve their English. Student K, for example, said, “In my blog, I always used words I already knew, so I didn’t feel I was making any progress”. Several students likened blogging to writing a diary, stating that

blogging was too informal to be as effective as writing a traditional essay in terms of pushing them to learn language forms. As this student noted:

When blogging, you write whatever is on your mind, but when writing a formal essay, you have to have an introduction, a conclusion, transition signals, things like that. The teacher could have required us to do more things like this in our blogs. (J)

Preliminary results from questionnaire data collected in phase 2

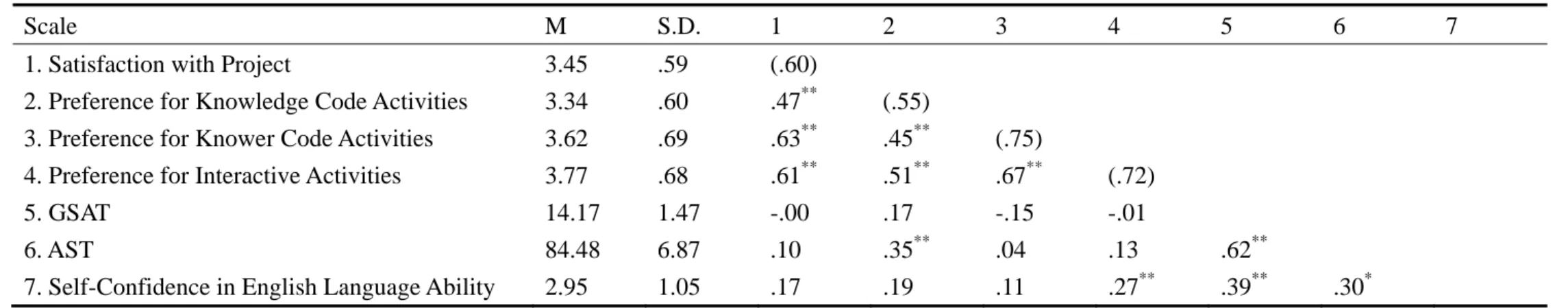

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, internal-consistency reliabilities, and correlations among the scales of the questionnaire. The alpha reliabilities for the scales of Satisfaction with the Project, Preference for Knower Code Activities, and Preference for Interaction, were all above .60, although the alpha reliability for the scale of Preference for Knowledge Code Activities was .55. This could be due to the exploratory nature of the study, for which a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .60 is acceptable (Robinson, Shaver & Wrightsman, 1991).

High mean scores ranging from 3.34 for the scale of Preference for Knowledge Code Activities to 3.77 for the scale of Preference for Interaction on a five point Likert type scale revealed that students generally had a positive perception of the project and all three kinds of activities involved in the project.

Using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), it was found that the amount of variance in scores accounted by class membership was not statistically significant for the scales of Satisfaction with the Project (F = .941, p >.10), GSAT (F = .029, p >.10), AST (F = 1.508, p >.10), and

Self-Confidence in English Language Ability (F = .416, p >.10). This indicates that the students’ perceptions of the project were not affected by which class they were drawn from, and that their English language proficiency and confidence levelswere similar. Therefore, students in the three classes were treated as a homogenous group.

Correlation analysis showed that Satisfaction with the Project had a positive relationship with three scales: Preference for Knowledge Code Activities (r = .47, p < .01), Knower Code Activities (r = .63, p < .01), and Preference for Interaction (r = .61, p < .01).On the other hand, the other three scales - GSAT (r = -.00, p > .01), AST (r = .10, p > .01), and Self-Confidence in English Language

12

Ability (r = .17, p > .01) - were not significantly related to Satisfaction with the Project.Preference for Knowledge Code Activities was also positively associated with three scales: Preference for Knower Code Activities (r = .45, p < .01), Preference for Interaction (r = .51, p < .01), and AST (r = .35, p < .01). Preference for Knower Code Activities was positively associated with Preference for Interaction (r = .67, p < .01), and Preference for Interaction was positively related to

Self-Confidence in English Language Ability (r = .27, p < .01).

However, although both Preference for Knowledge Code Activities and Preference for Knower Code Activities were significantly positively related to Satisfaction with the Project, after

controlling the effects of Preference for Interaction, the statistical significance of differences on the Preference for Knower Code Activities scale was found to be greater than that reported for the Preference for Knowledge Code Activities scale (Preference for Knowledge Code Activities Satisfaction with the Project, standardized β coefficient = .170, t = 1.897, p < .10; Preference for Knower Code Activities Satisfaction with the Project, standardized β coefficient = .376, t = 3.592, p < .01). That is, despite knowledge code and knower code learning orientations both contributed to learners’ satisfaction with the project, a knower code learning orientation led to greater satisfaction with the project than a knowledge code learning orientation.

Finally, regression analysisindicated that GSAT (t = .76, p > .10), AST (t = -.035, p > .10) and Self-Confidence in English Language Ability (t = 1.613, p > .10) did not significantly predict learners’ Satisfaction with the Project.

13

Table 4. Scale Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), Internal Consistency (Cronbach Alpha Reliability), and Correlations among Scales

Scale M S.D. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Satisfaction with Project 3.45 .59 (.60) 2. Preference for Knowledge Code Activities 3.34 .60 .47** (.55) 3. Preference for Knower Code Activities 3.62 .69 .63** .45** (.75)

4. Preference for Interactive Activities 3.77 .68 .61** .51** .67** (.72)

5. GSAT 14.17 1.47 -.00 .17 -.15 -.01

6. AST 84.48 6.87 .10 .35** .04 .13 .62**

7. Self-Confidence in English Language Ability 2.95 1.05 .17 .19 .11 .27** .39** .30*

Note.Cronbach’s alpha coefficients appear on the diagonal. n = 93. GSAT = the General Scholastic Ability Test (The scaled score ranges from 0 to 15); AST = the Advanced Subjects Test (Each test is worth 100 points).

14 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Findings based on the interview data collected in first phase of the study indicated that learners who were more satisfied with the blog project shared a number of characteristics: they had strong

passion for, and claimed expertise in, the knowledge they shared on their blogs. This enthusiasm and confidence was accompanied by a palpable ambition to teach their audience about what they knew. They also developed ownership of their work, seeing it as reflecting part of their selves. Together, these themes revealed that satisfied earners recognized the knowledge they had obtained in their personal life as valid knowledge in educational settings, such as in the blog project. As illustrated in the result section, they thrived at being allowed to bring their personal knowledge to the blogging environment, through which they shared the social aspects of themselves with people inside and outside school. This emphasis on the socially-based characteristics of the learner as the basis of legitimate insights indicated that the social relation characterizing this group’s educational dispositions was relatively strong (SR+). Moreover, while highlighting the personal knowledge displayed in their own and their peers’ blogs, they downplayed the significance of English language skills. Even when discussing their language improvement, satisfied earners accentuated how it had become easier for them to express their thoughts (the “who”) rather than on the attainment of language skills (the “what” and “how”). The relative de-emphasis on language skills embodied a weaker epistemic relation (ER-). In short, satisfied earners demonstrated relatively strong “knower code” (ER-, SR+) educational dispositions, which was compatible with the knower code

pedagogical design of the project.

On the other hand, learners who were less satisfied with the project experienced it very differently to the previous group. They suffered from having little to write and did not deem what they wrote to be of value to themselves and to others. Put another way, they felt their personal insights not worth sharing, that is, a downplaying of their socially-based attributes. This

de-emphasis on the social aspects of the learner was also exemplified by two students’ suppression of expressing their personal views on their blogs, and another student’s remark that if everyone wrote on the same topic, she could use her classmates’ writing as a yardstick to measure her language performance, indicating that what mattered to her regarding the existence of peers in a learning context was not who they were or what they thought, but the language skills they possessed. The social relation characterizing these students’ educational dispositions was thus relatively weak (SR-). In addition, their comments regarding the project’s drawbacks in offering them new language skills to learn (the “what”) manifested an emphasis on the epistemic relation (ER+). Together, the specialization code represented by less-satisfied learners’ educational dispositions was a

“knowledge code” (ER+, SR-), an opposite code to the one characterizing the learning environment. In short, phase 1 of the study found that differences in individual learners’ educational

dispositions led to their more, or less, positive blogging experiences. Those who prospered in the project were pre-equipped with the attributes assumed by the pedagogical design, which made them the “right” kind of knowers for the project. On the other hand, those who were less satisfied with

15

the project entered the learning environment with dispositions not agreeable to the environment, thus becoming the “wrong” kind of knowers for the project.

Finally, preliminary analysis of the questionnaire data collected in the second phase of the study indicated that learners’ satisfaction with the project was not influenced by their English language proficiency, self-confidence in their English language ability, or their class membership. Although the results suggested that the project slightly favored learners with a preference for knower code activities, it should be noted that the results also showed that preferences for

knowledge code and knower code activities both led to satisfaction with the project. Analysis of the interview data collected in phase 2 will hopefully shed some light on these results.

REFERENCES

Absalom, M., & De Saint Léger, D. (2011). Reflecting on reflection: Learner perceptions of diaries and blogs in tertiary language study. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 10(2), 189-211.

Alm, A. (2009). Blogging for self-determination with L2 learner journals. In M. Thomas (Ed.),

Handbook of Research on Web 2.0 and Second Language Learning (pp. 202-222). Hershey,

PA: Information Science Reference.

Bhattacharya, A., & Chauhan, K. (2010). Augmenting learner autonomy through blogging. ELT

Journal, 64(4), 376-384.

Bloch, J. (2007). Abdullah's blogging: A generation 1.5 student enters the blogosphere.

Language Learning & Technology, 11(2), 128-141.

Carney, N. (2009). Blogging in foreign language education. In M. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of

Research on Web 2.0 and Second Language Learning (pp. 292–312). Hershey, PA:

Information Science Reference.

Chen, R.T.-H., Maton, K., & Bennett, S. (2011). Absenting discipline: Non-disciplinarity in online learning. In F. Christie & K. Maton (Eds.), Disciplinarity: Functional Linguistic and

Sociological Perspectives (pp. 129-150). London: Continuum.

Comas-Quinn, A., Mardomingo, R., & Valentine, C. (2009). Mobile blogs in language learning: making the most of informal and situated learning opportunities. ReCALL, 21(1), 96-112. Lee, L. (2010). Fostering reflective writing and interactive exchange through blogging in an

advanced language course. ReCALL, 22(2), 212-227.

Maton, K. (2007). Knowledge-knower structures in intellectual and educational fields. In F. Christie & J. R. Martin (Eds.), Language, knowledge and pedagogy: Functional linguistic and

sociological perspectives (pp. 87-108). London: Continuum.

Maton, K. (2014). Knowledge and Knowers: Towards a Realist Sociology of Education, London: Routledge.

Miceli, T., Murray, S. V., & Kennedy, C. (2010). Using an L2 blog to enhance learners' participation and sense of community. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(4),

16 321-341.

Mompean, A. R. (2010). The development of meaningful interactions on a blog used for the learning of English as a foreign language. ReCALL, 22, 376-395.

Murray, L., & Hourigan, T. (2008). Blogs for specific purposes: Expressivist or socio-cognitivist approach? ReCALL, 20(1), 82-97.

Richardson, W. (2006). Blogs, Wikis, Podcasts, and Other Powerful Web Tools for Classrooms. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press.

Robinson, J. P., Shaver P. R., and Wrightsman, L. S. (1991). Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, and L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of

Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes (pp.1-16). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Sun, Y-C. (2009). Voice blog: An exploratory study of language learning. Language Learning &

Technology, 13(2), 88-103.

Thorne, S. L., & Payne, J. S. (2006). Evolutionary trajectories, Internet-mediated expression, and language education. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 371-397.

Vurdien, R. (2011). Enhancing writing skills through blogging in an advanced English as a Foreign Language class in Spain. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(2), 126-143.

1

國科會補助專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心得報告

日期:102 年 7 月 25 日一、參加會議經過

兩年一度的WorldCALL年會2013年由北愛爾蘭的Ulster大學和WorldCALL共同主辦,會議地點為蘇 格蘭格拉斯哥的展覽及會議中心(Scottish Exhibition & Conference Centre)。參與本次會議人士超過 300人,所發表論文約200篇。每一個時段有9篇論文同時發表,主題十分豐富,類別涵蓋Research papers, CALL for Development, Research and Development, Reflective Practice, Symposium 和 Colloquium。此外,在午餐時段安排了海報展示(Poster Session),每日議程最後一小時安排了課程 軟體示範(Courseware Demos)。我在會議開始前一天傍晚到達飯店,隔日(7/10)至會議地點報到,熟 悉環境,並將我要發表的論文做最後修改。7/11日我專心聆聽與會學者的發表,上午場次印象較深 刻的是紐西蘭學者 Karen Haines的研究論文Learning for the long haul: Developing perceptions of learning affordances in CALL teachers。雖然我原先就熟悉affordances的概念,但Haines的論文重新提 醒了我affordances的一些相關概念。本日的重頭戲為Diane Larsen-Freeman教授的plenary speech了, 內容是她的 Complexity Theory,以及使用新科技學習語言時實踐這個理論的潛力,Larsen-Freeman 教授無法親自到場,她以視訊方式演說,但在大會細心安排下,效果很好。下午場次中我印象較深 的是美國Arizona大學Jonathon Reinhardt的發表,他主要是分析數位遊戲英語教學文獻中所用到的理 論架構,所涵蓋內容豐富。雖然數位遊戲英語教學並非我的專門領域,但去了解跟我完全不同領域 也是我參加本次會議的目的之一,這個場次我收穫許多。 我的論文排在7/12日上午場次,發表之前,我先聆聽了比利時Antwerp大學Jozef Colpaert教 授的plenary speech,Colpaert教授探討現今CALL領域和CALL學者們所面對的挑戰,在會議前幾天 就線上調查了與會人士對所屬機構對他們學術工作的評量標準是否滿意,而在他演說過程中也利用 即時網路調查方式與觀眾針對他的演說內容做互動。我的論文發表完後便專心聆聽其他學者的發計畫編號

NSC101-2410-H-004-165計畫名稱

以社會學觀點探究英語學習者之部落格寫作經驗出國人員

姓名

陳彩虹服務機構

及職稱

政治大學外文中心助理教授會議時間

102/7/10 ~102/7/13會議地點

蘇格蘭格拉斯哥會議名稱

(中文) 2013 世界電腦輔助英語教學會議 (英文) 2013 WorldCALL發表論文

題目

(中文)語言學習者撰寫部落格經驗差異之探討(英文)Investigating the reasons behind language learners’ differing perceptions of blogging

2

表。最後一天(7/13)的plenary speech由來自智利Concepción大學的 Emerita Bañados-Santana教授主 講,內容是她在過去十年來所領導發展出來的一個線上英語課程。本日場次我印象最深刻的是澳洲 昆士蘭大學Mike Levy教授的論文,他對目前CALL領域使用非第二語言習得理論的普遍性提出疑 問,該發表引發在場觀眾相當熱烈的辯論。

二、與會心得

今年是我第一次參加 WorldCALL 年會,我發現此會議含有高比例的台灣學者,說明了台灣學者對 此領域的高度興趣,以及在這個領域的成就。我在會議上碰到幾位在日本教學與研究多年的西方 學者,這些學者所探討的問題跟台灣學者很類似,藉由與他們的討論,我對日本的英語教學現狀 多了一些平時讀研究報告讀不到的了解,這樣的訊息難能可貴。另外,我察覺到在 CALL 領域扮 演領導角色的學者們目前最關心的議題似乎是如何為此領域下定義。這個問題我也很想得到解 答:為什麼 CALL 有自成一個領域的必要?它與一般英語教學領域的界線在哪裡?譬如,為什麼「電 腦輔助科學教學」沒有獨立成為一個領域?若原因在於語言學習有它與其他學門不同的學習理 論,那麼是不是說有牽涉到語言學習理論的研究才屬於 CALL,也就是說嚴格說來,CALL 是否有 必要排除不屬於這個狹窄定義的研究?我個人認為,若 CALL 領域真如此做,該領域必然更加縮 小,是否能生存下去可能是更大的問題。換句話說,今天 CALL 領導者在擔憂的現象,也許從好 的方面來說,正是讓 CALL 有機會成為一個領域的重要原因。例如,Mike Levy 教授提出對太多非 第二語言習得理論進入 CALL 領域是否會阻礙 CALL 理論發展的擔憂,雖然有他的道理,但不論 是第二語言習得理論或是非第二語言習得理論,能幫助我們「解釋」和「預測」(就如 Levy 在他演 說中所強調)現象的理論就是有力的理論,而無法做到這些的,不論是否為第二語言習得理論,自 然會被淘汰。三、發表論文全文或摘要

There is currently a large amount of literature examining language learners’ experiences with blogging. While blogging has generally been seen to benefit learners, contrasting experiences among individual learners have also been identified. To investigate what may cause such differences, this paper draws on one dimension of Maton’s Legitimation Code Theory to explore 33 Taiwanese university students’ blogging experiences in an elective English course. The study sought to identify the ideal blogger in a language learning context by analyzing 1) the coding orientation learners bring to the blogging context, 2) the code underpinning the pedagogical design of the project, and 3) the relations between these two sets of codes.

In the ten week project, students wrote individual blogs on their self-chosen topics. They were required to write one post on their blogs and respond to two of their classmates’ blogs every week. Data was collected using a questionnaire and individual interviews with ten of the students. The study found that learners who reported receiving more benefits shared a number of characteristics, which in the terms of the code theory was specialized by a ‘knower code’ (where learners’ dispositions are emphasized as the basis of achievement). On the other hand, less satisfied learners demonstrated a stronger ‘knowledge code’ learning orientation (which emphasizes explicit procedures, skills and specialized knowledge). The

3

‘code match’ and ‘code clash’ between the learning orientations of the two groups of learners and the teaching design will be discussed. The paper argues that this was one important factor that gave rise to the differences in learner perceptions of the blog project.

四、建議

本會議將 research papers、reflective practice 和 courseware demos 三類作品做區分的安排,我覺得 很好,讓與會者能較正確地選擇感興趣的場次參加。以往我參加 e-learning 類的大型研討會常將這 幾類發表(尤其是 research papers 和 reflective practice)混淆。建議國內辦大型英語教學研討會時考慮 這樣的做法,將研究論文與教學實施與成果評鑑類的論文做區別。

五、攜回資料名稱及內容

World CALL 2013 Programme and Abstract Book.

六、其他

無國科會補助計畫衍生研發成果推廣資料表

日期:2013/10/17國科會補助計畫

計畫名稱: 以社會學觀點探究英語學習者之部落格寫作經驗 計畫主持人: 陳彩虹 計畫編號: 101-2410-H-004-165- 學門領域: 英語教學研究無研發成果推廣資料

101 年度專題研究計畫研究成果彙整表

計畫主持人:陳彩虹 計畫編號: 101-2410-H-004-165-計畫名稱:以社會學觀點探究英語學習者之部落格寫作經驗 量化 成果項目 實際已達成 數(被接受 或已發表) 預期總達成 數(含實際已 達成數) 本計畫實 際貢獻百 分比 單位 備 註 ( 質 化 說 明:如 數 個 計 畫 共 同 成 果、成 果 列 為 該 期 刊 之 封 面 故 事 ... 等) 期刊論文 0 1 100% 研究報告/技術報告 1 1 100% 研討會論文 0 1 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國內 參與計畫人力 (本國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次 期刊論文 0 1 100% 研究報告/技術報告 0 0 100% 研討會論文 1 1 100% 篇 論文著作 專書 0 0 100% 章/本 申請中件數 0 0 100% 專利 已獲得件數 0 0 100% 件 件數 0 0 100% 件 技術移轉 權利金 0 0 100% 千元 碩士生 0 0 100% 博士生 0 0 100% 博士後研究員 0 0 100% 國外 參與計畫人力 (外國籍) 專任助理 0 0 100% 人次其他成果

(無法以量化表達之成

果如辦理學術活動、獲 得獎項、重要國際合 作、研究成果國際影響 力及其他協助產業技 術發展之具體效益事 項等,請以文字敘述填 列。) 無 成果項目 量化 名稱或內容性質簡述 測驗工具(含質性與量性) 0 課程/模組 0 電腦及網路系統或工具 0 教材 0 舉辦之活動/競賽 0 研討會/工作坊 0 電子報、網站 0 科 教 處 計 畫 加 填 項 目 計畫成果推廣之參與(閱聽)人數 0國科會補助專題研究計畫成果報告自評表

請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況、研究成果之學術或應用價

值(簡要敘述成果所代表之意義、價值、影響或進一步發展之可能性)

、是否適

合在學術期刊發表或申請專利、主要發現或其他有關價值等,作一綜合評估。

1. 請就研究內容與原計畫相符程度、達成預期目標情況作一綜合評估

■達成目標

□未達成目標(請說明,以 100 字為限)

□實驗失敗

□因故實驗中斷

□其他原因

說明:

2. 研究成果在學術期刊發表或申請專利等情形:

論文:□已發表 □未發表之文稿 ■撰寫中 □無

專利:□已獲得 □申請中 ■無

技轉:□已技轉 □洽談中 ■無

其他:(以 100 字為限)

在本計畫下已發表一篇國際研討會論文,並已投稿一篇期刊論文:Chen, R.T.-H. (2013). Investigating the reasons behind language learners' differing perceptions of blogging. Paper presented at WorldCALL 2013, Glasgow, Scotland.

Chen, R.T.-H. (under review). L2 blogging: Who thrives and who does not? Language Learning & Technology.